1. Introduction

The Short bowel syndrome (SBS) in adults is defined as having less than 180 to 200 cm of remaining small bowel (normal length varies from 275 to 850 cm) [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The occurrence of SBS in the overall population is approximately 1-2 cases per 100,000 inhabitants per year. In the USA, the incidence ranges from 0.3 to 4 cases per 100,000 inhabitants per year, while in Europe, it varies from 0.1 to 4 cases per 100,000 inhabitants per year. [

5]. Many literature sources do not provide precise epidemiological data, and challenges in estimating the prevalence of SBS include its multifactorial etiology and varying definitions [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. The most common pathologies leading to SBS include Crohn disease, mesenteric ischemia, radiation enteritis, post-surgical adhesions, and post

-operative complications [

1,

2,

4,

5,

6]. Intestinal resection surgery leads to considerable reduction in the absorptive surface area of the intestine, causing the loss of essential nutrients, changes in gastrointestinal motility and microbiota, and the development of malabsorption. Clinical manifestations of malabsorption include weight loss, diarrhea, steatorrhea, dehydration, nutritional deficiency, and electrolyte imbalance [

1,

2,

3,

4,

6].

In severe cases of SBS, parenteral nutrition (PN) might become necessary to administer essential nutrients directly into the bloodstream, circumventing the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) [

1,

8,

10]. Alternatively, nutrition can be administered enterally by introducing mixtures into the GIT through an enteral tube or stoma, or by a combination of these artificial feeding methods [

11,

12]. Enteral nutrition (EN) is the preferred method due to its lower complication rates and cost-effectiveness. However, in situations where enteral feeding is not possible or GIT dysfunction is present, full parenteral nutrition (FPN) becomes necessary, utilizing the circulatory system as the sole source of nutrients. The main indications for PN and EN are listed in

Table 1. EN is commonly required for neurological diseases and cancer, while PN is indicated in cases of SBS, malabsorption, and mechanical obstruction of the GIT [

13,

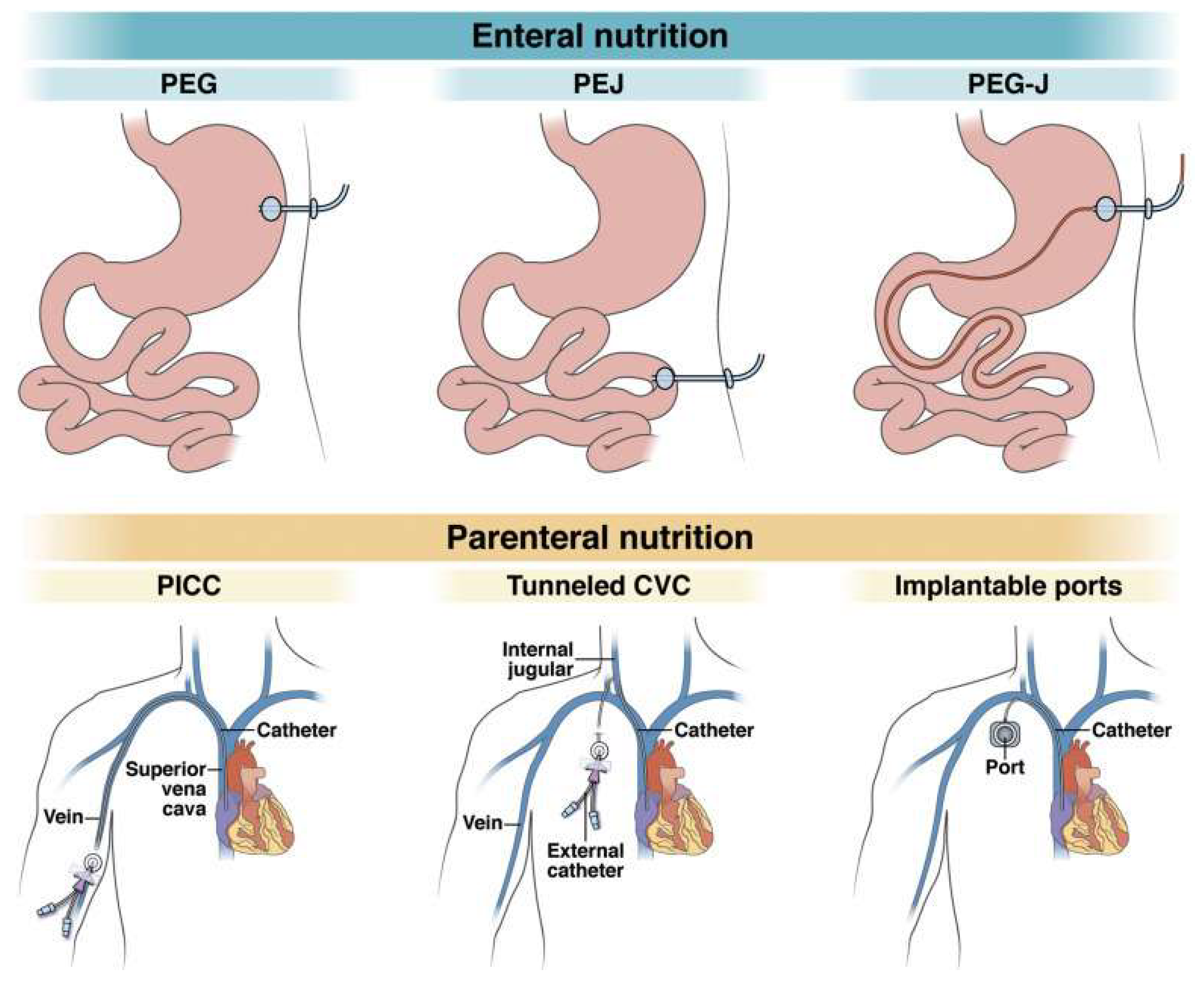

14]. EN requires the presence of an enteral tube or stoma. There are three percutaneous endoscopic methods of enteral feeding: gastrostomy, jejunostomy, and gastrojejunostomy. The choice of approach depends on the underlying disease, the patient's nutritional tolerance, and the anatomy of the GIT. In cases where it is not possible to perform an endoscopic procedure, radiological or surgical methods are applied.

For long-term PN, three types of venous access are utilized: a peripheral vein central catheter, a tunneled central vein catheter, and an implantable Ports catheter. These catheters are positioned to end in either the superior vena cava or the right atrium. The access routes for EN and PN are illustrated in

Figure 1 [

13,

14]. The clinical case presented in this article aims to emphasize the importance of PN in ensuring the acquisition of all essential micro- and macronutrients in critically ill patients with SBS.

2. Case report

A 76-year-old man with symptoms of abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting was urgently admitted to the Department of Esophageal, Gastric, and Endocrine Surgery, on the 1st of October 2022.

The patient has a medical history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, glaucoma, arterial hypertension, chronic atrial fibrillation, benign prostatic hyperplasia, gout, heart failure, bronchial asthma, and ischemic heart disease. Upon examination, the abdomen reveals scarring from previous surgeries, with tenderness on palpation around the umbilicus and on the right side, but no other significant changes. Abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT) scans indicate signs of small bowel obstruction. Initially, conservative treatment was administered, and a nasogastric tube was inserted. However, due to the lack of a positive response, the patient underwent urgent surgery, which included laparotomy, adhesiolysis, release of the small bowel loop, ligation of the strangulating ligament, and drainage of the Douglas cavity. The post-operative diagnosis was mechanical ileus.

Due to postoperative respiratory function insufficiency (RFI) and peritonitis-induced disturbance of homeostasis, with an ongoing need for mechanical ventilation (MV), the patient was transferred to the central reanimation (CR) unit. In the CR, electrolyte imbalance was corrected, and infusion therapy and empirical antibiotic therapy were continued, along with thromboembolism and stress gastric ulcer prophylaxis. Following stabilization of the patient's condition and observation of positive changes in inflammatory markers, the patient was transferred to the Colon and Perineal Surgery Unit (CPSU) for further treatment after 3 days.

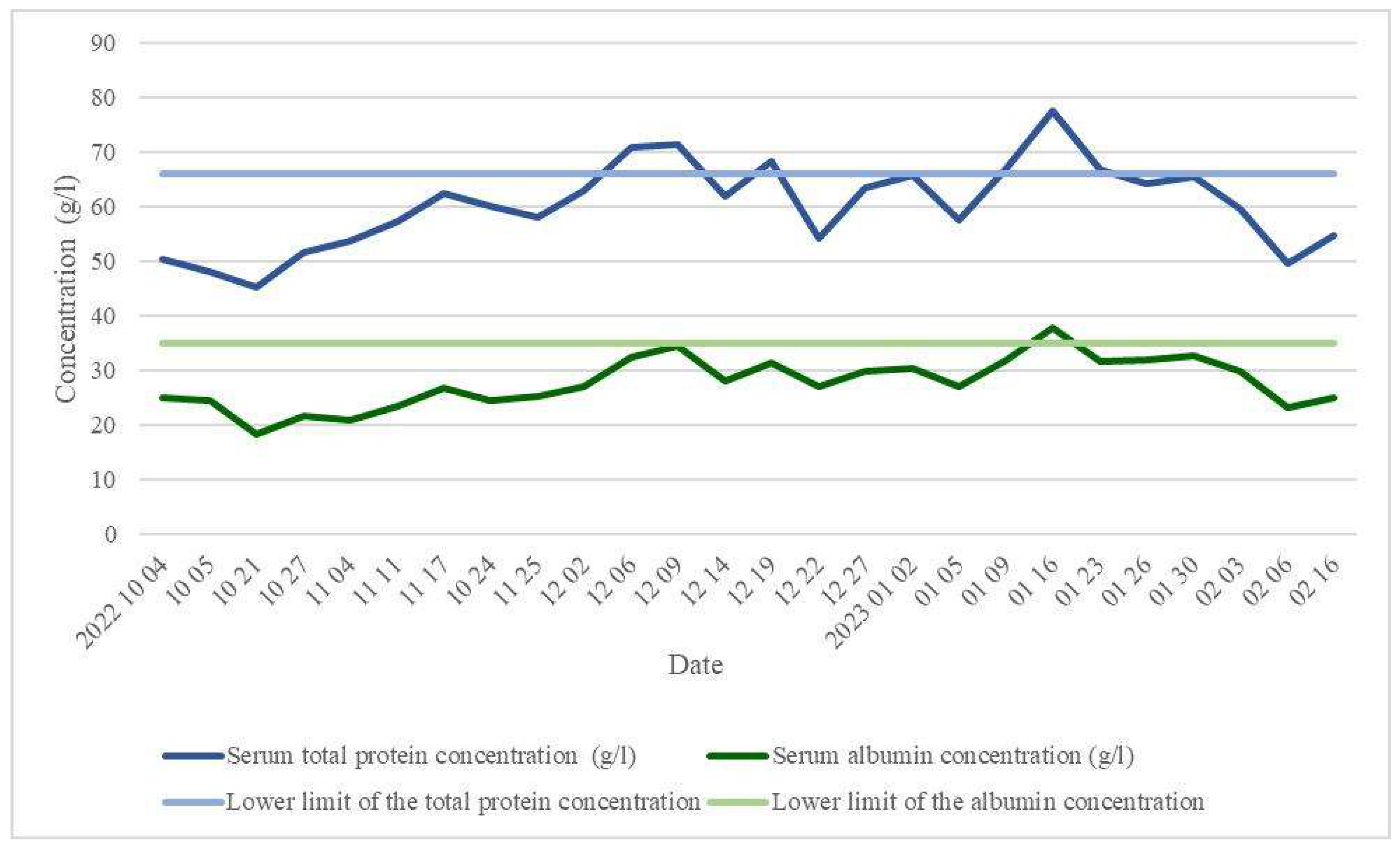

Laboratory blood tests were performed to assess the patient's nutritional status, monitoring hypoproteinaemia of 50.3 g/l on October 4, 2022, and hypoalbuminaemia of 24.5 g/l on October 5, 2022 (

Figure 2). As part of the treatment plan, a semi-pureed food (SPF) diet was prescribed, with the addition of 2 bottles of special mix Diasip and 500 ml of 10 % Aminoven intravenously daily.

Five days after the first surgery, the patient developed a fever up to 40°C, and abdominal pain emerged. Following an abdominal X-ray examination, a positive progression of bowel obstruction was observed. As the mentioned symptoms progressed, an abdominal and pelvic CT scan was performed, and stercoral peritonitis was diagnosed. The patient underwent urgent relaparotomy, during which 20 cm of necrotic and perforated small bowel above the sutured strangulated area was resected. Peritoneal lavage and drainage were performed, and a two-tube jejunostomy was created, leaving approximately 60 cm of small bowel from the ligament of Treitz. A preliminary diagnosis of short bowel syndrome (SBS) was made.

Due to postoperative RFI, sepsis and septic shock, the patient was transferred to CR unit. Noradrenaline was administered for perfusion support, along with MV, infusion therapy, prophylaxis for stress ulcers and thromboembolism, correction of electrolyte imbalance, and antibiotic treatment. After vasoconstrictor support was gradually reduced and hemodynamics stabilized, and with an ongoing oxygen therapy requirement of 6 l/min, the patient was transferred to the CPSU after 4 days. During the course of treatment, the patient's condition improved, and instrumental examinations showed positive echoscopic and radiological dynamics, with signs of intestinal obstruction and stercoral peritonitis regressing.

Approximately 1 week after the second surgery, with SBS and serum total protein levels at 45.3 g/l and albumin at 18.3 g/l (on October 21, 2022), falling below the lower limit of normal (

Figure 2), the patient received nutritional support. After catheterizing the right internal jugular vein, full parenteral nutrition (FPN) was initiated, involving SmofKabiven Central infusion emulsion, as well as micro-nutrients and vitamin concentrates of Soluvit, Addaven, and Vitalipid. To maintain the trophicity of intestinal villi, the patient continued with an oral SPF diet. For further enhancement of the nutritional status, the patient was admitted to the Nutritional Unit for symptomatic treatment and FPN from December 5, 2022, until January 31, 2023, in preparation for the planned reconstructive bowel surgery.

In a stable condition, following the correction of hypoproteinaemia (increased from 63.0 g/l on December 2, 2022, to 65.5 g/l on January 30, 2023) and hypoalbuminaemia (elevated from 27.0 gl/l on December 2, 2022, to 32.8 g/l on January 30, 2023) (

Figure 2), reconstructive bowel surgery was performed, involving laparotomy and closure of the ileostoma. FPN was continued for 2 weeks postoperatively, bringing the total duration to 4 months (from October 17, 2022, to February 16, 2023).

After the restoration of intestinal integrity and a return to a normal diet, the patient’s parenteral nutrition (PN) was discontinued, and their nutritional status was corrected (total protein 54.8 g/l and albumin 25.1 g/l on February 16, 2023). Subsequently, the patient was discharged home for further outpatient treatment under the care of a family doctor.

3. Discussion

Parenteral nutrition (PN) is a mixture of solutions containing dextrose, amino acids, electrolytes, vitamins, minerals, and trace elements. However, the precise formulation and rate of administration are customized to meet the unique nutritional and fluid needs of each individual patient [

15]. PN is recommended when oral or enteral feeding proves insufficient to fulfill nutritional needs, or when there are contraindications to these methods, such as hemodynamic instability, intestinal obstruction, severe vomiting or diarrhea, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, or intestinal ischemia [

16].

In cases of short bowel syndrome (SBS), the length of residual bowel is measured from the duodenojejunal flexure to the ileocecal junction, the site of any small bowel–colon anastomosis or to the end-ostomy.

Based on the presence or absence of residual colon, SBS patients may be classified into 3 groups: group 1, end-jejunostomy; group 2, jejunum anastomosed to partial colon (jejunocolonic anastomosis); and group 3, jejuno-ileo-colic anastomosis, retaining entire colon and ileocecal valve. It is crucial to highlight that the third group exhibits the most favorable prognosis for survival, while the first group presents the least favorable outcome, comprising patients with the most severe condition. [

17,

18].

The primary goals for patients with SBS involve expediting the restoration of both the small and large intestines’ integrity, reestablishing the proper function and transit of the distal colon, and enhancing the functionality of the remaining intestines through specialized lengthening or narrowing surgeries to reduce reliance on PN. Each bowel reconstruction procedure is customized on an individual basis [

18]. The restoration of bowel integrity is achieved via small and large bowel re-anastomosis. Following this procedure, remarkably low mortality rates are observed, and the probability of requiring a return to PN during the post-operative period is exceedingly minimal [

19,

20].

Patients afflicted with SBS complicated by intestinal insufficiency undergo autologous gastrointestinal reconstructive surgery, the choice of method is based on the existing bowel length, function, and caliber. As SBS advances, bowel segments undergo expansion to compensate for the diminished surface area and length. When peristalsis slows down and intestinal segments dilate, the most common surgical interventions involve reducing the intestinal radius while preserving the current absorptive surface area. These procedures include longitudinal intestinal lengthening and tapering (LILT) following the Bianchi technique or serial transverse enteroplasty (STEP). In patients with rapid peristalsis but no dilation, segmental reversal of the small bowel (SRSB) or isoperistaltic colonic interposition is performed to decelerate the evacuation of bowel contents [

19,

20]. In the clinical case described, a stoma was removed, and an anastomosis connecting the small and large intestine was performed to reinstate intestinal integrity.

Following intestinal resection surgery, the gastrointestinal adaptation process initiates, and it can be categorized into three distinct phases based on duration and physiological characteristics. Phase 1, spanning 1-3 months, is characterized by potentially severe diarrhea and diminished intestinal absorption. During this period, PN is utilized to meet nutrient and fluid requirements to avert intestinal failure, nitrogen imbalance, and significant sudden weight loss. As the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) becomes able to absorb food, enteral nutrition (EN) is introduced in the early post-operative phase. This approach stimulates intestinal adaptation through three mechanisms: mucosal hyperplasia, secretion of gastrointestinal hormones, and pancreato-biliary system juices and enzymes. Phase 2, lasting up to 1 month, involves the action of remaining intestinal hormones and growth factors that facilitate functional and structural changes in the GIT. This adaptation enables the rest of the intestinal tract to recover and improve absorption by reducing fluid loss and enhancing the assimilation of micro- and macro-elements. Consequently, PN is gradually decreased in favor of increased EN. Phase 3, which may extend up to two years, signifies the period of maximum intestinal adaptation. During this stage, PN is either discontinued or significantly reduced to a minimum level as the gastrointestinal system attains its peak adaptive state [

17].

Patients receiving PN in combination with EN have better treatment outcomes than those receiving PN alone. One of the key factors contributing to this observation is the reduced risk of complications, including infection and adverse metabolic reactions such as hyperglycemia, serum electrolyte imbalances, and excessive or insufficient levels of macro- and micro-elements. Moreover, the occurrence of hepatic impairment and challenges related to venous access are also lessened with the implementation of combined nutrition therapy [

15]. This clinical case illustrates that maintaining an adequate intake of essential nutrients may result in the patient's nutritional status remaining below the lower limit of normal during most of the treatment period. Despite the combination of full parenteral nutrition (FPN) and oral intake, it appears that the provided amount of food was insufficient, as evidenced by the patient's 15 kg weight loss over the 4-month treatment period. This occurred against a backdrop of nutritional deficiency, previous interventions, and increased nutritional demands in the postoperative phase (weight decreased from 110 kg on 6

th October 2022 to 95 kg on 6

th February 2023). However, it is noteworthy that this change in body weight did not significantly affect the overall condition and outcome of the patient.

PN can be administered to fulfill all necessary nutrient requirements or used as a supplement to enteral feeding. The present clinical case demonstrates that both approaches can complement each other effectively. In this case, partial EN provided trophic support for the intestinal goblet cells, while PN ensured the patient's intake of essential nutrients.

4. Conclusions

In cases of malnutrition where oral or enteral feeding is impossible or contraindicated, the use of temporary or permanent parenteral nutrition can prove to be a life-saving intervention. After successfully restoring nutritional status and discontinuing artificial feeding, and in the absence of intestinal insufficiency and dilatation, the most effective surgical method to restore intestinal integrity is through small and large bowel re-anastomosis. For patients for whom bowel reconstruction surgery is not a viable option, parenteral nutrition remains the sole path that leads to a more favorable outcome and ensures the preservation of their quality of life.

Author Contributions

conceptualization, S.Š. and I.S.; methodology, S.Š..; software, I.S. and R.V.; validation, S.Š., I.S. and R.V.; formal analysis, S.Š., I.S. and R.V.; investigation, S.Š., I.S. and R.V.; resources, S.Š., I.S. and R.V.; data curation, S.Š., I.S. and R.V.; writing—original draft preparation, I.S. and R.V..; writing—review and editing, S.Š., I.S. and R.V.; visualization, I.S. and R.V.; supervision, S.Š.; project administration, S.Š.; funding acquisition, I.S. and R.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This manuscript does not include any details, images, or videos relating to an individual person.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Guillen B, Atherton NS. Short Bowel Syndrome. Pediatric Surgery Diagnosis and Management. 2022 Jul 26;1015–29.

- Bioletto F, D’eusebio C, Merlo FD, Aimasso Nutrients. 2022 Feb 1;14(4).

- Pironi L. Definitions of intestinal failure and the short bowel syndrome. Best Practice and Research Clinical Gastroenterology. 2016 Apr 1;30(2):173–85. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui MT, Al-Yaman W, Singh A, Kirby DF. Short-Bowel Syndrome: Epidemiology, Hospitalization Trends, In-Hospital Mortality, and Healthcare Utilization. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2021 Sep 1;45(7):1441–55. [CrossRef]

- The Living Textbook of Medicine. Available from: https//www.wikidoc.org/index.php/Short_bowel_syndrome_epidemiology_and_demographics (accessed on 18 August 2023).

- Rare Disease Database. Available from: https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/short-bowel-syndrome/ (accessed on 18 August 2023).

- UpToDate. Available from: https://medilib.ir/uptodate/show/4770 (accessed on 18 August 2023).

- Singer P, Berger MM, Van den Berghe G, Biolo G, Calder P, Forbes A, et al. ESPEN Guidelines on Parenteral Nutrition: intensive care. Clinical Nutrition. 2009;28(4):387–400. [CrossRef]

- McClave SA, Taylor BE, Martindale RG, Warren MM, Johnson DR, Braunschweig C, et al. Guidelines for the Provision and Assessment of Nutrition Support Therapy in the Adult Critically Ill Patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.). JPEN Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2016;40(2):159–211. [CrossRef]

- Clinical Nutrition. St James’s Hospital. Available from: https://stjames.ie/services/scope/clinicalnutrition/ (accessed on 18 August 2023).

- D’Cruz JR, Cascella M. Feeding Jejunostomy Tube. Radiopaedia. 2022 Jul 25.

- Lietuvos parenterinės ir enterinės mitybos draugija. Available from: https:www/lpemd.org/gaires/ (accessed on 18 August 2023).

- Kovacevich DS, Corrigan M, Ross VM, McKeever L, Hall AM, Braunschweig C. American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition Guidelines for the Selection and Care of Central Venous Access Devices for Adult Home Parenteral Nutrition Administration. JPEN Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2019 Jan 1;43(1):15–31. [CrossRef]

- Hadefi A, Arvanitakis M. How to Approach Long-term Enteral and Parenteral Nutrition. Journal of Gastroenterology. Volume 161, Issue 6, P1780-1786, December 2021. [CrossRef]

- UpToDate. Available from: https://medilib.ir/uptodate/show/1617 (accessed on 18 August 2023).

- Worthington P, Balint J, Bechtold M, Bingham A, Chan LN, Durfee S, et al. When Is Parenteral Nutrition Appropriate? JPEN Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2017 Mar 1;41(3):324–77. [CrossRef]

- Lakkasani S, Seth D, Khokhar I, Touza M, Dacosta TJ. Concise review on short bowel syndrome: Etiology, pathophysiology, and management. World Journal of Clinical Cases. 2022 Nov 11;10(31):11273. [CrossRef]

- Iyer K, DiBaise JK, Rubio-Tapia A. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Management of Short Bowel Syndrome: Expert Review. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2022 Oct 1;20(10):2185-2194. [CrossRef]

- UpToDate. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/management-of-short-bowel-syndrome-in-adults (accessed on 18 August 2023).

- Iyer KR. Surgical management of short bowel syndrome. JPEN Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2014 May 1;38:53S-59S.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).