Submitted:

28 August 2023

Posted:

29 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

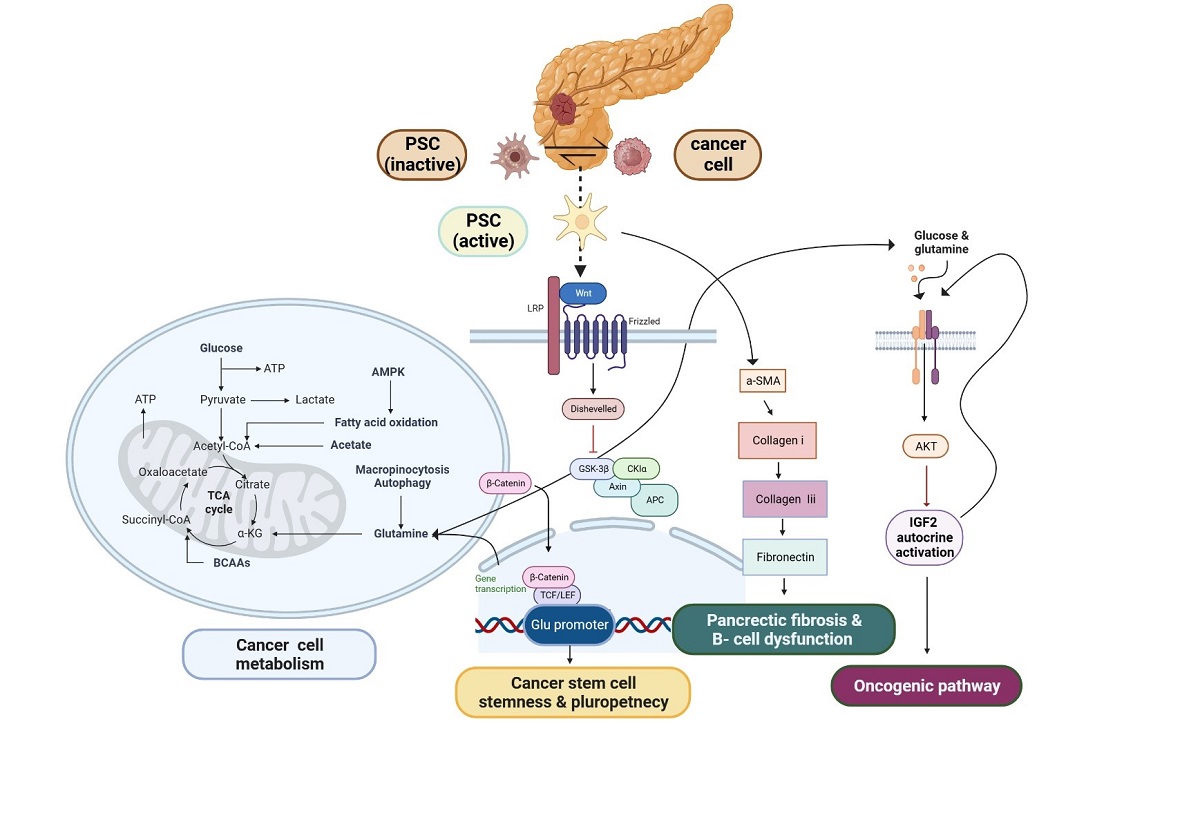

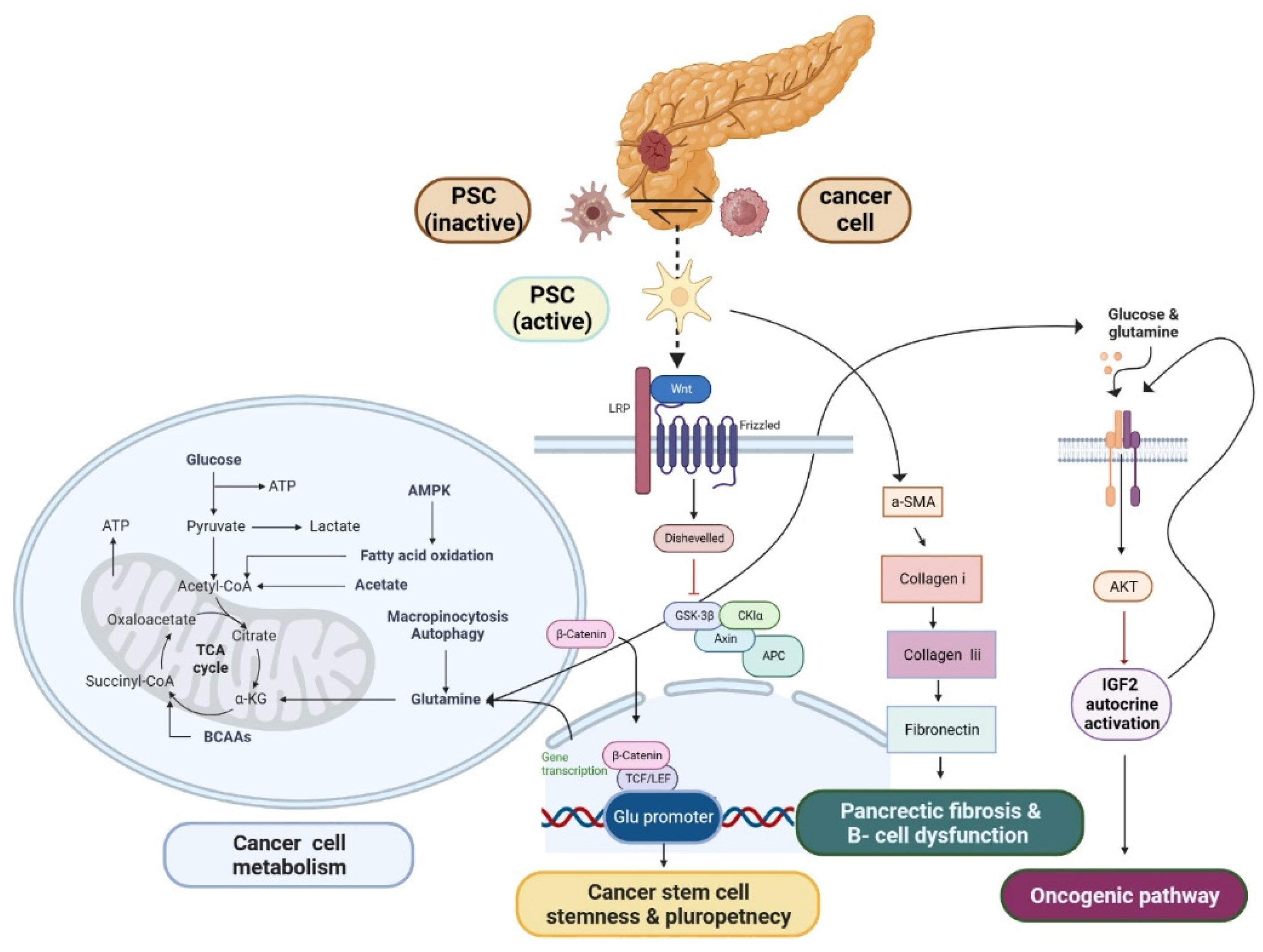

PSC have emerged as a promising candidate for stem cell in PDAC

Type 2 diabetes is a significant prognostic indicator for pancreatic cancer

Diabetes management strategies may reduce the risk of pancreatic cancer

Herbal medicine in vitro assay

Natural compound in clinical trial

Tendency in FDA-Approved Therapies

2. Conclusions

Funding

References

- Quante, A.S.; Ming, C.; Rottmann, M.; Engel, J.; Boeck, S.; Heinemann, V.; Westphalen, C.B.; Strauch, K. Projections of cancer incidence and cancer-related deaths in Germany by 2020 and 2030. Cancer Med. 2016, 5, 2649–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; et al. Locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: are we making progress?. Highlights from the "2011 ASCO Annual Meeting". Chicago, IL, USA; June 3-7, 2011. Jop, 2011. 12(4): p. 347-50.

- Thakur, G.; Kumar, R.; Kim, S.-B.; Lee, S.-Y.; Lee, S.-L.; Rho, G.-J. Therapeutic Status and Available Strategies in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizrahi, J.D.; et al. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet 2020, 395, 2008–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, Y.; Gong, Y.; Fan, Z.; Luo, G.; Huang, Q.; Deng, S.; Cheng, H.; Jin, K.; Ni, Q.; Yu, X.; et al. Molecular alterations and targeted therapy in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biankin, A.V.; Waddell, N.; Kassahn, K.S.; Gingras, M.-C.; Muthuswamy, L.B.; Johns, A.L.; Miller, D.K.; Wilson, P.J.; Patch, A.-M.; Wu, J.; et al. Pancreatic cancer genomes reveal aberrations in axon guidance pathway genes. Nature 2012, 491, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yachida, S.; et al. Clinical significance of the genetic landscape of pancreatic cancer and implications for identification of potential long-term survivors. Clin Cancer Res 2012, 18, 6339–6347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowery, M.A.; Jordan, E.J.; Basturk, O.; Ptashkin, R.N.; Zehir, A.; Berger, M.F.; Leach, T.; Herbst, B.; Askan, G.; Maynard, H.; et al. Real-Time Genomic Profiling of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: Potential Actionability and Correlation with Clinical Phenotype. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 6094–6100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, N.; et al. Whole genomes redefine the mutational landscape of pancreatic cancer. Nature 2015, 518, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lito, P.; Solomon, M.; Li, L.-S.; Hansen, R.; Rosen, N. Allele-specific inhibitors inactivate mutant KRAS G12C by a trapping mechanism. Science 2016, 351, 604–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.R.; O’reilly, E.M. New Treatment Strategies for Metastatic Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Drugs 2020, 80, 647–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masamune, A.; Shimosegawa, T. Signal transduction in pancreatic stellate cells. J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 44, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erkan, M.; Reiser-Erkan, C.; Michalski, C.W.; Deucker, S.; Sauliunaite, D.; Streit, S.; Esposito, I.; Friess, H.; Kleeff, J. Cancer-Stellate Cell Interactions Perpetuate the Hypoxia-Fibrosis Cycle in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Neoplasia 2009, 11, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachem, M.G.; Schneider, E.; Groß, H.; Weidenbach, H.; Schmid, R.M.; Menke, A.; Siech, M.; Beger, H.; Grünert, A.; Adler, G. Identification, culture, and characterization of pancreatic stellate cells in rats and humans. Gastroenterology 1998, 115, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apte, M.V.; Wilson, J.S.; Lugea, A.; Pandol, S.J. A Starring Role for Stellate Cells in the Pancreatic Cancer Microenvironment. Gastroenterology 2013, 144, 1210–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, M.A.; Dangi-Garimella, S.; Redig, A.J.; Munshi, H.G. Biochemical role of the collagen-rich tumour microenvironment in pancreatic cancer progression. Biochem. J. 2011, 441, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neesse, A.; Algül, H.; A Tuveson, D.; Gress, T.M. Stromal biology and therapy in pancreatic cancer: a changing paradigm. Gut 2015, 64, 1476–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waghray, M.; Yalamanchili, M.; di Magliano, M.P.; Simeone, D.M. Deciphering the role of stroma in pancreatic cancer. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2013, 29, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apte, M.V.; Haber, P.S.; Darby, S.J.; Rodgers, S.C.; Mccaughan, G.W.; Korsten, M.A.; Pirola, R.C.; Wilson, J.S. Pancreatic stellate cells are activated by proinflammatory cytokines: implications for pancreatic fibrogenesis. Gut 1999, 44, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incio, J.; et al. Obesity-Induced Inflammation and Desmoplasia Promote Pancreatic Cancer Progression and Resistance to Chemotherapy. Cancer Discov 2016, 6, 852–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomiyama, Y.; Tashiro, M.; Yamaguchi, T.; Watanabe, S.; Taguchi, M.; Asaumi, H.; Nakamura, H.; Otsuki, M. High Glucose Activates Rat Pancreatic Stellate Cells Through Protein Kinase C and p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Pathway. Pancreas 2007, 34, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, S.-H.; Hong, O.-K.; Kim, J.-W.; Ahn, Y.-B.; Song, K.-H.; Cha, B.-Y.; Son, H.-Y.; Kim, M.-J.; Jeong, I.-K.; Yoon, K.-H. High glucose increases extracellular matrix production in pancreatic stellate cells by activating the renin–angiotensin system. J. Cell. Biochem. 2006, 98, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, G.R.; Lee, E.; Chun, H.-J.; Yoon, K.-H.; Ko, S.-H.; Ahn, Y.-B.; Song, K.-H. Oxidative stress plays a role in high glucose-induced activation of pancreatic stellate cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 439, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, K.; Baghy, K.; Spisák, S.; Szanyi, S.; Tulassay, Z.; Zalatnai, A.; Löhr, J.-M.; Jesenofsky, R.; Kovalszky, I.; Firneisz, G. Chronic Hyperglycemia Induces Trans-Differentiation of Human Pancreatic Stellate Cells and Enhances the Malignant Molecular Communication with Human Pancreatic Cancer Cells. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0128059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Waldron, R.T.; Su, H.-Y.; Moro, A.; Chang, H.-H.; Eibl, G.; Ferreri, K.; Kandeel, F.R.; Lugea, A.; Li, L.; et al. Insulin promotes proliferation and fibrosing responses in activated pancreatic stellate cells. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 2016, 311, G675–G687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; et al. PSC-derived Galectin-1 inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells by activating the NF-κB pathway. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 86488–86502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, X.; Liu, M.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, Y.; He, R.; Gao, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. Hypoxia activated HGF expression in pancreatic stellate cells confers resistance of pancreatic cancer cells to EGFR inhibition. EBioMedicine 2022, 86, 104352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Gao, W.; Lytle, N.K.; Huang, P.; Yuan, X.; Dann, A.M.; Ridinger-Saison, M.; DelGiorno, K.E.; Antal, C.E.; Liang, G.; et al. Targeting LIF-mediated paracrine interaction for pancreatic cancer therapy and monitoring. Nature 2019, 569, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biffi, G.; Tuveson, D.A. Diversity and Biology of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts. Physiol. Rev. 2021, 101, 147–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augstein, P.M.; Loudovaris, T.; Bandala-Sanchez, E.; Heinke, P.M.; Naselli, G.B.; Lee, L.; Hawthorne, W.J.; Góñez, L.J.; Neale, A.M.B.; Vaillant, F.; et al. Characterization of the Human Pancreas Side Population as a Potential Reservoir of Adult Stem Cells. Pancreas 2018, 47, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, E.R.; Menezes, S.; Henry, J.C.; Williams, J.L.; Alba-Castellón, L.; Baskaran, P.; Quétier, I.; Desai, A.; Marshall, J.J.; Rosewell, I.; et al. Disruption of pancreatic stellate cell myofibroblast phenotype promotes pancreatic tumor invasion. Cell Rep. 2022, 38, 110227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Shi, Y.; Qian, F. Opportunities and delusions regarding drug delivery targeting pancreatic cancer-associated fibroblasts. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 172, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; et al. Asporin promotes pancreatic cancer cell invasion and migration by regulating the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) through both autocrine and paracrine mechanisms. Cancer letters 2017, 398, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ma, Q.; Huang, R.; Lu, J.; Liang, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, L.; Pang, J.; et al. YAP1-mediated pancreatic stellate cell activation inhibits pancreatic cancer cell proliferation. Cancer Lett. 2019, 462, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamphorst, J.J.; Nofal, M.; Commisso, C.; Hackett, S.R.; Lu, W.; Grabocka, E.; Vander Heiden, M.G.; Miller, G.; Drebin, J.A.; Bar-Sagi, D.; et al. Human Pancreatic Cancer Tumors Are Nutrient Poor and Tumor Cells Actively Scavenge Extracellular Protein. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 544–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Guo, W.; Liu, Q.; Chen, L.; Pang, J.; Liu, X.; Li, R.; Tong, W.-M.; et al. Pancreatic stellate cells exploit Wnt/β-catenin/TCF7-mediated glutamine metabolism to promote pancreatic cancer cells growth. Cancer Lett. 2023, 555, 216040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, T.; Dai, C.; Martell, E.; Ghassemi-Rad, M.S.; Hanes, M.R.; Murphy, P.J.; Kennedy, B.E.; Venugopal, C.; Subapanditha, M.K.; Giacomantonio, C.A.; et al. TAp73 Modifies Metabolism and Positively Regulates Growth of Cancer Stem–Like Cells in a Redox-Sensitive Manner. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 2001–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaggupilli, A.; Ly, S.; Nguyen, K.; Anand, V.; Yuan, B.; El-Dana, F.; Yan, Y.; Arvanitis, Z.; Piyarathna, D.W.B.; Putluri, N.; et al. Metabolic stress induces GD2+ cancer stem cell-like phenotype in triple-negative breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 126, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukha, A.; Kahya, U.; Linge, A.; Chen, O.; Löck, S.; Lukiyanchuk, V.; Richter, S.; Alves, T.C.; Peitzsch, M.; Telychko, V.; et al. GLS-driven glutamine catabolism contributes to prostate cancer radiosensitivity by regulating the redox state, stemness and ATG5-mediated autophagy. Theranostics 2021, 11, 7844–7868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, M.; et al. xCT inhibition depletes CD44v-expressing tumor cells that are resistant to EGFR-targeted therapy in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res 2013, 73, 1855–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Fu, Z.; Chen, R.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zeng, B.; Yu, M.; Zhou, Q.; Lin, Q.; Gao, W.; et al. Inhibition of glutamine metabolism counteracts pancreatic cancer stem cell features and sensitizes cells to radiotherapy. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 31151–31163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modi, H.; Cornu, M.; Thorens, B. Glutamine Stimulates Biosynthesis and Secretion of Insulin-like Growth Factor 2 (IGF2), an Autocrine Regulator of Beta Cell Mass and Function. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 31972–31982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouwens, L.; Houbracken, I.; Mfopou, J.K. The use of stem cells for pancreatic regeneration in diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2013, 9, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gargett, C.E.; Schwab, K.E.; Deane, J.A. Endometrial stem/progenitor cells: the first 10 years. Hum Reprod Update 2016, 22, 137–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apte, M.V.; Pirola, R.C.; Wilson, J.S. Pancreatic stellate cells: a starring role in normal and diseased pancreas. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, F.-X.; Morahan, G. Pancreatic Stem Cells Remain Unresolved. Stem Cells Dev. 2014, 23, 2803–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, P., Pancreatic stellate cells and fibrosis (Pancreatic Cancer and Tumor Microenvironment). Kerala, India: Transworld Research Network, 2012.—Р. 29. 53.

- Nielsen, M.F.B.; Mortensen, M.B.; Detlefsen, S. Identification of markers for quiescent pancreatic stellate cells in the normal human pancreas. Histochem. 2017, 148, 359–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, M.; Li, F.; Xu, W.; Chen, B.; Sun, Z. Isolation and characterization of islet stellate cells in rat. Islets 2014, 6, e28701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, G.; Sandberg, M.; Carlsson, P.-O.; Welsh, N.; Jansson, L.; Barbu, A. Activated pancreatic stellate cells can impair pancreatic islet function in mice. Upsala J. Med Sci. 2015, 120, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Ryu, G.R.; Ko, S.-H.; Ahn, Y.-B.; Song, K.-H. A role of pancreatic stellate cells in islet fibrosis and β-cell dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 485, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Sun, B.; Li, W.; Zhou, J.; Gao, F.; Wang, X.; Cai, M.; Sun, Z. Pancreatic Stellate Cells: A Rising Translational Physiology Star as a Potential Stem Cell Type for Beta Cell Neogenesis. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zulewski, H.; Abraham, E.J.; Gerlach, M.J.; Daniel, P.B.; Moritz, W.; Müller, B.; Vallejo, M.; Thomas, M.K.; Habener, J.F. Multipotential Nestin-Positive Stem Cells Isolated From Adult Pancreatic Islets Differentiate Ex Vivo Into Pancreatic Endocrine, Exocrine, and Hepatic Phenotypes. Diabetes 2001, 50, 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, E.J.; et al. Insulinotropic Hormone Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Differentiation of Human Pancreatic Islet-Derived Progenitor Cells into Insulin-Producing Cells. Endocrinology 2002, 143, 3152–3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skoglund, G.; A Hussain, M.; Holz, G.G. Glucagon-like peptide 1 stimulates insulin gene promoter activity by protein kinase A-independent activation of the rat insulin I gene cAMP response element. Diabetes 2000, 49, 1156–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buteau, J.; Roduit, R.; Susini, S.; Prentki, M. Glucagon-like peptide-1 promotes DNA synthesis, activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and increases transcription factor pancreatic and duodenal homeobox gene 1 (PDX-1) DNA binding activity in beta (INS-1)-cells. Diabetologia 1999, 42, 856–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrose-Rafizadeh, C.; et al. Pancreatic glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor couples to multiple G proteins and activates mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Endocrinology 1999, 140, 1132–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, T.; Ito, T.; Uchida, M.; Hijioka, M.; Igarashi, H.; Oono, T.; Kato, M.; Nakamura, K.; Suzuki, K.; Jensen, R.T.; et al. PSCs and GLP-1R: occurrence in normal pancreas, acute/chronic pancreatitis and effect of their activation by a GLP-1R agonist. Lab. Investig. 2014, 94, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagwandin, V.J.; Shay, J.W. Pancreatic cancer stem cells: Fact or fiction? Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) Molecular Basis of Disease 2009, 1792, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschmann-Jax, C.; Foster, A. E.; Wulf, G. G.; Nuchtern, J. G.; Jax, T. W.; Gobel, U.; Goodell, M. A.; Brenner, M. K. A distinct "side population" of cells with high drug efflux capacity in human tumor cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 14228–14233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, F.; Luo, B.; Wang, X.; Sun, H.; Liu, S.; Cui, Y.; Xu, X. A side population of cells from a human pancreatic carcinoma cell line harbors cancer stem cell characteristics. Neoplasma 2009, 56, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiwata, T.; Matsuda, Y.; Yoshimura, H.; Sasaki, N.; Ishiwata, S.; Ishikawa, N.; Takubo, K.; Arai, T.; Aida, J. Pancreatic cancer stem cells: features and detection methods. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2018, 24, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mato, E.; Lucas, M.; Petriz, J.; Gomis, R.; Novials, A. Identification of a pancreatic stellate cell population with properties of progenitor cells: new role for stellate cells in the pancreas. Biochem. J. 2009, 421, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kordes, C.; Sawitza, I.; Götze, S.; Häussinger, D. Stellate Cells from Rat Pancreas Are Stem Cells and Can Contribute to Liver Regeneration. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e51878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zha, M.; Xu, W.; Jones, P.M.; Sun, Z. Isolation and characterization of human islet stellate cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2016, 341, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, T.C.Y.; Wilson, J.S.; Apte, M.V. Pancreatic stellate cells: what's new? Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2017, 33, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacifico, F.; Leonardi, A.; Crescenzi, E. Glutamine Metabolism in Cancer Stem Cells: A Complex Liaison in the Tumor Microenvironment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joharatnam-Hogan, N.; Morganstein, D.L. Diabetes and cancer: Optimising glycaemic control. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 36, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avgerinos, K.I.; Spyrou, N.; Mantzoros, C.S.; Dalamaga, M. Obesity and cancer risk: Emerging biological mechanisms and perspectives. Metabolism 2019, 92, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, S.S.; Huh, J.Y.; Hwang, I.J.; Kim, J.I.; Kim, J.B. Adipose Tissue Remodeling: Its Role in Energy Metabolism and Metabolic Disorders. Front. Endocrinol. 2016, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jernås, M.; Palming, J.; Sjöholm, K.; Jennische, E.; Svensson, P.-A.; Gabrielsson, B.G.; Levin, M.; Sjögren, A.; Rudemo, M.; Lystig, T.C.; et al. Separation of human adipocytes by size: hypertrophic fat cells display distinct gene expression. FASEB J. 2006, 20, 1540–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregor, M.F.; Hotamisligil, G.S. Inflammatory Mechanisms in Obesity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 29, 415–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutkowski, J.M.; Stern, J.H.; Scherer, P.E. The cell biology of fat expansion. J. Cell Biol. 2015, 208, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coe, P.O.; Williams, S.R.; Morris, D.M.; Parkin, E.; Harvie, M.; Renehan, A.G.; O'Reilly, D.A. Development of MR quantified pancreatic fat deposition as a cancer risk biomarker. Pancreatology 2018, 18, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebours, V.; Gaujoux, S.; D'Assignies, G.; Sauvanet, A.; Ruszniewski, P.; Lévy, P.; Paradis, V.; Bedossa, P.; Couvelard, A. Obesity and Fatty Pancreatic Infiltration Are Risk Factors for Pancreatic Precancerous Lesions (PanIN). Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 3522–3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.G.; Nguyen, N.N.; Cervantes, A.; Alarcon Ramos, G.C.; Cho, J.; Petrov, M.S. Associations between intra-pancreatic fat deposition and circulating levels of cytokines. Cytokine 2019, 120, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Hori, M.; Ishigamori, R.; Mutoh, M.; Imai, T.; Nakagama, H. Fatty pancreas: A possible risk factor for pancreatic cancer in animals and humans. Cancer Sci. 2018, 109, 3013–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollak, M. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor signalling in neoplasia. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2008, 8, 915–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarty, A.W.; Glancy, C.; Jones, S.; A Lewis, S.; McKeever, T.M.; Britton, J.R. A prospective study of weight change and systemic inflammation over 9 y. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’brien, K.D.; Brehm, B.J.; Seeley, R.J.; Bean, J.; Wener, M.H.; Daniels, S.; D’alessio, D.A. Diet-Induced Weight Loss Is Associated with Decreases in Plasma Serum Amyloid A and C-Reactive Protein Independent of Dietary Macronutrient Composition in Obese Subjects. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 2244–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.-H.; Moro, A.; Takakura, K.; Su, H.-Y.; Mo, A.; Nakanishi, M.; Waldron, R.T.; French, S.W.; Dawson, D.W.; Hines, O.J.; et al. Incidence of pancreatic cancer is dramatically increased by a high fat, high calorie diet in KrasG12D mice. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0184455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-J.; Dai, H.-Q.; Huang, X.-W.; Feng, J.; Deng, J.-H.; Wang, Z.-X.; Yang, X.-M.; Liu, Y.-J.; Wu, Y.; Chen, P.-H.; et al. Artesunate synergizes with sorafenib to induce ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020, 42, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turchi, R.; et al. Frataxin deficiency induces lipid accumulation and affects thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue. Cell Death Dis 2020, 11, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; et al. Diabetic Ferroptosis and Pancreatic Cancer: Foe or Friend? Antioxid Redox Signal 2022, 37, 1206–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Xiao, L.; Liu, L.; Ye, L.; Su, P.; Bi, E.; Wang, Q.; Yang, M.; Qian, J.; Yi, Q. CD36-mediated ferroptosis dampens intratumoral CD8+ T cell effector function and impairs their antitumor ability. Cell Metab. 2021, 33, 1001–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Shukaili, A.; Al-Ghafri, S.; Al-Marhoobi, S.; Al-Abri, S.; Al-Lawati, J.; Al-Maskari, M. Analysis of Inflammatory Mediators in Type 2 Diabetes Patients. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2013, 2013, 976810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, M.C.; Shulman, G.I. Mechanisms of Insulin Action and Insulin Resistance. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 2133–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höppener, J.W.; Ahrén, B.; Lips, C.J. Islet Amyloid and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. New Engl. J. Med. 2000, 343, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permert, J.; Larsson, J.; Westermark, G.T.; Herrington, M.K.; Christmanson, L.; Pour, P.M.; Westermark, P.; Adrian, T.E. Islet Amyloid Polypeptide in Patients with Pancreatic Cancer and Diabetes. New Engl. J. Med. 1994, 330, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuzillet, C.; de Gramont, A.; Tijeras-Raballand, A.; de Mestier, L.; Cros, J.; Faivre, S.; Raymond, E. Perspectives of TGF-β inhibition in pancreatic and hepatocellular carcinomas. Oncotarget 2013, 5, 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longnecker, D.S.; Gorelick, F.; Thompson, E.D. Anatomy, histology, and fine structure of the pancreas. The pancreas: an integrated textbook of basic science, medicine, and surgery, 2018: p. 10-23.

- Pannala, R.; Basu, A.; Petersen, G.M.; Chari, S.T. New-onset diabetes: a potential clue to the early diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, R.P.; Nagpal, S.J.S.; Mukhopadhyay, D.; Chari, S.T. New insights into pancreatic cancer-induced paraneoplastic diabetes. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 10, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, C.J.; Falasca, M.; Chari, S.T.; Greenfield, J.R.; Xu, Z.; Pirola, R.C.; Wilson, J.S.; Apte, M.V. Role of Pancreatic Stellate Cell-Derived Exosomes in Pancreatic Cancer-Related Diabetes: A Novel Hypothesis. Cancers 2021, 13, 5224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagpal, S.J.S.; Kandlakunta, H.; Sharma, A.; Sannapaneni, S.; Velamala, P.; Majumder, S.; Matveyenko, A.; Chari, S.T. Endocrinopathy in Pancreatic Cancer Is Characterized by Reduced Islet Size and Density with Preserved Endocrine Composition as Compared to Type 2 Diabetes: Presidential Poster Award. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 113, S26–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Morley, T.S.; Kim, M.; Clegg, D.J.; Scherer, P.E. Obesity and cancer—mechanisms underlying tumour progression and recurrence. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2014, 10, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haass, C.; Koo, E.H.; Mellon, A.; Hung, A.Y.; Selkoe, D.J. Targeting of cell-surface β-amyloid precursor protein to lysosomes: alternative processing into amyloid-bearing fragments. Nature 1992, 357, 500–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, G.J.; Willis, A.C.; Clark, A.; Turner, R.C.; Sim, R.B.; Reid, K.B. Purification and characterization of a peptide from amyloid-rich pancreases of type 2 diabetic patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1987, 84, 8628–8632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janson, J.; Laedtke, T.; Parisi, J.E.; O’brien, P.; Petersen, R.C.; Butler, P.C. Increased Risk of Type 2 Diabetes in Alzheimer Disease. Diabetes 2004, 53, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hmidene, A.; Hanaki, M.; Murakami, K.; Irie, K.; Isoda, H.; Shigemori, H. Inhibitory Activities of Antioxidant Flavonoids from Tamarix gallica on Amyloid Aggregation Related to Alzheimer’s and Type 2 Diabetes Diseases. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2017, 40, 238–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M.; Murakami, K.; Uno, M.; Nakagawa, Y.; Katayama, S.; Akagi, K.-I.; Masuda, Y.; Takegoshi, K.; Irie, K. Site-specific Inhibitory Mechanism for Amyloid β42 Aggregation by Catechol-type Flavonoids Targeting the Lys Residues. PEDIATRICS 2013, 288, 23212–23224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M.; Murakami, K.; Uno, M.; Ikubo, H.; Nakagawa, Y.; Katayama, S.; Akagi, K.-I.; Irie, K. Structure–Activity Relationship for (+)-Taxifolin Isolated from Silymarin as an Inhibitor of Amyloid β Aggregation. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2013, 77, 1100–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KURISU, M.; et al. Inhibition of Amyloid β Aggregation by Acteoside, a Phenylethanoid Glycoside. Bioscience Biotechnology and Biochemistry 2013, 77, 1329–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbari, B.; Baghaei-Yazdi, N.; Bahmaie, M.; Abhari, F.M. The role of plant-derived natural antioxidants in reduction of oxidative stress. BioFactors 2022, 48, 611–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuengsamarn, S.; Rattanamongkolgul, S.; Luechapudiporn, R.; Phisalaphong, C.; Jirawatnotai, S. Curcumin Extract for Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 2121–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, S.; Liao, Q.; Chen, X.; Peng, C.; Lin, L. The role of irisin in metabolic flexibility: Beyond adipose tissue browning. Drug Discov. Today 2022, 27, 2261–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leyva-Soto, A.; Chavez-Santoscoy, R.A.; Porras, O.; Hidalgo-Ledesma, M.; Serrano-Medina, A.; Ramírez-Rodríguez, A.A.; Castillo-Martinez, N.A. Epicatechin and quercetin exhibit in vitro antioxidant effect, improve biochemical parameters related to metabolic syndrome, and decrease cellular genotoxicity in humans. Food Res. Int. 2021, 142, 110101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derochette, S.; Franck, T.; Mouithys-Mickalad, A.; Ceusters, J.; Deby-Dupont, G.; Lejeune, J.-P.; Neven, P.; Serteyn, D. Curcumin and resveratrol act by different ways on NADPH oxidase activity and reactive oxygen species produced by equine neutrophils. Chem. Interactions 2013, 206, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefian, M.; Shakour, N.; Hosseinzadeh, H.; Hayes, A.W.; Hadizadeh, F.; Karimi, G. The natural phenolic compounds as modulators of NADPH oxidases in hypertension. Phytomedicine 2018, 55, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaishree, V.; Narsimha, S. Swertiamarin and quercetin combination ameliorates hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia and oxidative stress in streptozotocin-induced type 2 diabetes mellitus in wistar rats. BioMedicine 2020, 130, 110561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.M.; et al. Metformin and reduced risk of cancer in diabetic patients. Bmj 2005, 330, 1304–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Yeung, S.J.; Hassan, M.M.; Konopleva, M.; Abbruzzese, J.L. Antidiabetic Therapies Affect Risk of Pancreatic Cancer. Gastroenterology 2009, 137, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartogh, D.J.D.; Tsiani, E. Antidiabetic Properties of Naringenin: A Citrus Fruit Polyphenol. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, P.A.; Law, R.J.; Frank, R.D.; Bamlet, W.R.; A Burch, P.; Petersen, G.M.; Rabe, K.G.; Chari, S.T. Impact of Diabetes Mellitus on Clinical Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Surgical Resection for Pancreatic Cancer: A Retrospective, Cohort Study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 109, 1484–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Chari, S.T. Pancreatic Cancer and Diabetes Mellitus. Curr. Treat. Options Gastroenterol. 2018, 16, 466–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, S.P.; et al. Early detection of pancreatic cancer. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020, 5, 698–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neoptolemos, J.P.; Kleeff, J.; Michl, P.; Costello, E.; Greenhalf, W.; Palmer, D.H. Therapeutic developments in pancreatic cancer: Current and future perspectives. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 15, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.E.; et al. Total Neoadjuvant Therapy With FOLFIRINOX Followed by Individualized Chemoradiotherapy for Borderline Resectable Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma: A Phase 2 Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol 2018, 4, 963–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, K.; Wang, F.; Ma, Q.; Li, Q.; Mallik, S.; Hsieh, T.-C.; Wu, E. Advances in Biomarker Research for Pancreatic Cancer. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2012, 18, 2439–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumlerdkij, N.; Tantiwongse, J.; Booranasubkajorn, S.; Boonrak, R.; Akarasereenont, P.; Laohapand, T.; Heinrich, M. Understanding cancer and its treatment in Thai traditional medicine: An ethnopharmacological-anthropological investigation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 216, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masek, A.; Chrzescijanska, E.; Latos, M.; Zaborski, M. Influence of hydroxyl substitution on flavanone antioxidants properties. Food Chem. 2017, 215, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amić, A.; Marković, Z.; Klein, E.; Marković, J.M.D.; Milenković, D. Theoretical study of the thermodynamics of the mechanisms underlying antiradical activity of cinnamic acid derivatives. Food Chem. 2018, 246, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.N.; Rahman, A.; Rahman, H.; Kim, J.W.; Choi, M.; Kim, J.W.; Choi, J.; Moon, M.; Ahmed, K.R.; Kim, B. Potential Therapeutic Implication of Herbal Medicine in Mitochondria-Mediated Oxidative Stress-Related Liver Diseases. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice-Evans, C.A.; Miller, N.J.; Paganga, G. Structure-antioxidant activity relationships of flavonoids and phenolic acids. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1996, 20, 933–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heijnen, C.; Haenen, G.; van Acker, F.; van der Vijgh, W.; Bast, A. Flavonoids as peroxynitrite scavengers: the role of the hydroxyl groups. Toxicol. Vitr. 2001, 15, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Acker, S.A.B.E.; Van Den Berg, D.-J.; Tromp, M.N.J.L.; Griffioen, D.H.; Van Bennekom, W.P.; Van Der Vijgh, W.J.F.; Bast, A. Structural aspects of antioxidant activity of flavonoids. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1996, 20, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiegel, M.; Andruniów, T.; Sroka, Z. Flavones' and Flavonols' Antiradical Structure-Activity Relationship-A Quantum Chemical Study. Antioxidants 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijnen, C.G.; Haenen, G.R.; Vekemans, J.A.; Bast, A. Peroxynitrite scavenging of flavonoids: structure activity relationship. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2001, 10, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Choi, Y.J.; Lee, J.H.; Nam, M.J. Naringenin causes ASK1-induced apoptosis via reactive oxygen species in human pancreatic cancer cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 99, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Zhang, F.; Yang, M.; Zhao, J.; Zeng, W.; Fang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liang, W. Naringenin Decreases Invasiveness and Metastasis by Inhibiting TGF-β-Induced Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition in Pancreatic Cancer Cells. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e50956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, D.-H.; Kim, J.H. Combined administration of naringenin and hesperetin with optimal ratio maximizes the anti-cancer effect in human pancreatic cancer via down regulation of FAK and p38 signaling pathway. Phytomedicine 2018, 58, 152762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Guo, W.; Cheung, F.; Tan, H.-Y.; Wang, N.; Feng, Y. Integrating Network Pharmacology and Experimental Models to Investigate the Efficacy of Coptidis and Scutellaria Containing Huanglian Jiedu Decoction on Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2020, 48, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, B. Traditional Chinese medicine network pharmacology: theory, methodology and application. Chinese Journal of Natural Medicines 2013, 11, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S. Network target: a starting point for traditional Chinese medicine network pharmacology. Zhongguo Zhong yao za zhi= Zhongguo zhongyao zazhi= China journal of Chinese materia medica 2011, 36, 2017–2020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Qian, X.; Chen, Z.; Chen, S.S.; Liu, L.M.; Zhang, A.Q. Integrated Analyses Identify Immune-Related Signature Associated with Qingyihuaji Formula for Treatment of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Using Network Pharmacology and Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network. J. Immunol. Res. 2020, 2020, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, P.-W.; Xu, P.-L.; Cheng, C.-S.; Jiao, J.-Y.; Wu, Y.; Dong, S.; Xie, J.; Zhu, X.-Y. Integrating network pharmacology and experimental models to investigate the efficacy of QYHJ on pancreatic cancer. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 297, 115516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, S.-K.; Cheng, K.-C.; Mgbeahuruike, M.O.; Lin, Y.-H.; Wu, C.-Y.; Wang, H.-M.D.; Yen, C.-H.; Chiu, C.-C.; Sheu, S.-J. New Insight into the Effects of Metformin on Diabetic Retinopathy, Aging and Cancer: Nonapoptotic Cell Death, Immunosuppression, and Effects beyond the AMPK Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, J.; Cheng, C.-S.; Xu, P.; Yang, P.; Zhang, K.; Jing, Y.; Chen, Z. Mechanisms of pancreatic tumor suppression mediated by Xiang-lian pill: An integrated in silico exploration and experimental validation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 298, 115586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, E.-J.; Kim, Y.; Lee, S.-H.; Ko, H.M.; Chung, W.-S.; Jang, H.-J. Anti-Cancer Potential of Oxialis obtriangulata in Pancreatic Cancer Cell through Regulation of the ERK/Src/STAT3-Mediated Pathway. Molecules 2020, 25, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relles, D.; et al. Thymoquinone promotes pancreatic cancer cell death and reduction of tumor size through combined inhibition of histone deacetylation and induction of histone acetylation. Advances in preventive medicine 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.; et al. Role of NF-κB in the anti-tumor effect of thymoquinone on bladder cancer. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2012, 92, 392–396. [Google Scholar]

- Muralidharan-Chari, V.; Kim, J.; Abuawad, A.; Naeem, M.; Cui, H.; Mousa, S.A. Thymoquinone Modulates Blood Coagulation in Vitro via Its Effects on Inflammatory and Coagulation Pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusufi, M.; Banerjee, S.; Mohammad, M.; Khatal, S.; Swamy, K.V.; Khan, E.M.; Aboukameel, A.; Sarkar, F.H.; Padhye, S. Synthesis, characterization and anti-tumor activity of novel thymoquinone analogs against pancreatic cancer. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 3101–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banik, K.; Khatoon, E.; Harsha, C.; Rana, V.; Parama, D.; Thakur, K.K.; Bishayee, A.; Kunnumakkara, A.B. Wogonin and its analogs for the prevention and treatment of cancer: A systematic review. Phytotherapy Res. 2022, 36, 1854–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, J.; Polier, G.; Köhler, R.; Giaisi, M.; Krammer, P.H.; Li-Weber, M. Wogonin and Related Natural Flavones Overcome Tumor Necrosis Factor-related Apoptosis-inducing Ligand (TRAIL) Protein Resistance of Tumors by Down-regulation of c-FLIP Protein and Up-regulation of TRAIL Receptor 2 Expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polier, G.; Ding, J.; Konkimalla, B.V.; Eick, D.; Ribeiro, N.; Köhler, R.; Giaisi, M.; Efferth, T.; Desaubry, L.; Krammer, P.H.; et al. Wogonin and related natural flavones are inhibitors of CDK9 that induce apoptosis in cancer cells by transcriptional suppression of Mcl-1. Cell Death Dis. 2011, 2, e182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlavcheski, F.; O’neill, E.J.; Gagacev, F.; Tsiani, E. Effects of Berberine against Pancreatitis and Pancreatic Cancer. Molecules 2022, 27, 8630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kallifatidis, G.; Hoy, J.J.; Lokeshwar, B.L. Bioactive natural products for chemoprevention and treatment of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2016, 40–41, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Zhu, P.; Chen, J.; Huang, Y. Traditional Chinese medicine as a cancer treatment: Modern perspectives of ancient but advanced science. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 1958–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Ha, J.; Kim, J.; Cho, Y.; Ahn, J.; Cheon, C.; Kim, S.-H.; Ko, S.-G.; Kim, B. Natural Products for Pancreatic Cancer Treatment: From Traditional Medicine to Modern Drug Discovery. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, C.; Tan, H.; Wang, N.; Chen, L.; Meng, Z.; Chen, Z.; Feng, Y. Functional inhibition of lactate dehydrogenase suppresses pancreatic adenocarcinoma progression. Clin. Transl. Med. 2021, 11, e467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotow, J.; Bivona, T.G. Understanding and targeting resistance mechanisms in NSCLC. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 637–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.W.; Han, J.-W. Targeting epigenetics for cancer therapy. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2019, 42, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staupe, H.; Buentzel, J.; Keinki, C.; Buentzel, J.; Huebner, J. Systematic analysis of mistletoe prescriptions in clinical studies. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 149, 5559–5571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthes, H.; Friedel, W.; Bock, P.; Zanker, K. Molecular Mistletoe Therapy: Friend or Foe in Established Anti-Tumor Protocols? A Multicenter, Controlled, Retrospective Pharmaco-Epidemiological Study in Pancreas Cancer. Curr. Mol. Med. 2010, 10, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedel, W.E.; Matthes, H.; Bock, P.R.; Zänker, K.S. Systematic evaluation of the clinical effects of supportive mistletoe treatment within chemo- and/or radiotherapy protocols and long-term mistletoe application in nonmetastatic colorectal carcinoma: multicenter, controlled, observational cohort study. J. Soc. Integr. Oncol. 2009, 7, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schad, F.; et al. Intratumoral Mistletoe (Viscum album L) Therapy in Patients with Unresectable Pancreas Carcinoma: A Retrospective Analysis. Integr Cancer Ther 2014, 13, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epelbaum, R.; Schaffer, M.; Vizel, B.; Badmaev, V.; Bar-Sela, G. Curcumin and Gemcitabine in Patients With Advanced Pancreatic Cancer. Nutr. Cancer 2010, 62, 1137–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahi, Y.; Saadat, A.; Beiraghdar, F.; Nouzari, S.M.H.; Jalalian, H.R.; Sahebkar, A. Antioxidant effects of bioavailability-enhanced curcuminoids in patients with solid tumors: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. J. Funct. Foods 2014, 6, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs-Tarlovsky, V. Role of antioxidants in cancer therapy. Nutrition 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, K.I.; Koch, A.C.; Mead, M.N.; Tothy, P.K.; Newman, R.A.; Gyllenhaal, C. Impact of antioxidant supplementation on chemotherapeutic efficacy: A systematic review of the evidence from randomized controlled trials. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2007, 33, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal, R.E.; Levy, C.; Turner, K.; Mathur, A.; Hughes, M.; Kammula, U.S.; Sherry, R.M.; Topalian, S.L.; Yang, J.C.; Lowy, I.; et al. Phase 2 Trial of Single Agent Ipilimumab (Anti-CTLA-4) for Locally Advanced or Metastatic Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. J. Immunother. 2010, 33, 828–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarchoan, M.; Hopkins, A.; Jaffee, E.M. Tumor Mutational Burden and Response Rate to PD-1 Inhibition. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 2500–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, M.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Y.; Das, A.; Vincent, B.G.; Li, J.; Liu, R.; Huang, L. Tumor neoantigen heterogeneity impacts bystander immune inhibition of pancreatic cancer growth. Transl. Oncol. 2020, 13, 100856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas, L.A.; Sethna, Z.; Soares, K.C.; Olcese, C.; Pang, N.; Patterson, E.; Lihm, J.; Ceglia, N.; Guasp, P.; Chu, A.; et al. Personalized RNA neoantigen vaccines stimulate T cells in pancreatic cancer. Nature 2023, 618, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.-J.; Tao, Z.; Gu, W.; Sun, L.-H. Variation of Blood T Lymphocyte Subgroups in Patients with Non- small Cell Lung Cancer. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2013, 14, 4671–4673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.-W.; Min, H.-Y. Ginseng, the 'Immunity Boost': The Effects of Panax ginseng on Immune System. J. Ginseng Res. 2012, 36, 354–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, I.; Ahn, G.; Park, E.; Ha, D.; Song, J.-Y.; Jee, Y. An acidic polysaccharide of Panax ginseng ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and induces regulatory T cells. Immunol. Lett. 2011, 138, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, I.-K.; Lee, K.Y.; Kang, J.; Park, J.S.; Jeong, J. Immune-modulating Effect of Korean Red Ginseng by Balancing the Ratio of Peripheral T Lymphocytes in Bile Duct or Pancreatic Cancer Patients With Adjuvant Chemotherapy. Vivo 2021, 35, 1895–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohal, D.P.S.; Kennedy, E.B.; Khorana, A.; Copur, M.S.; Crane, C.H.; Garrido-Laguna, I.; Krishnamurthi, S.; Moravek, C.; O’Reilly, E.M.; Philip, P.A.; et al. Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 2545–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohal, D.P.; Mangu, P.B.; Khorana, A.A.; Shah, M.A.; Philip, P.A.; O’reilly, E.M.; Uronis, H.E.; Ramanathan, R.K.; Crane, C.H.; Engebretson, A.; et al. Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 2784–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojania, K.G.; Sampson, M.; Ansari, M.T.; Ji, J.; Doucette, S.; Moher, D. How Quickly Do Systematic Reviews Go Out of Date? A Survival Analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007, 147, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, A.H.; A Tempero, M.; Shan, Y.-S.; Su, W.-C.; Lin, Y.-L.; Dito, E.; Ong, A.; Wang, Y.-W.; Yeh, C.G.; Chen, L.-T. A multinational phase 2 study of nanoliposomal irinotecan sucrosofate (PEP02, MM-398) for patients with gemcitabine-refractory metastatic pancreatic cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 109, 920–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conroy, T.; et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 2011, 364, 1817–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrag, D.; Archer, L.; Wang, X.; Romanus, D.; Mulcahy, M.; Goldberg, R.; Kindler, H. A patterns-of-care study of post-progression treatment (Rx) among patients (pts) with advanced pancreas cancer (APC) after gemcitabine therapy on Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) study #80303. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 4524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-Y.; Shen, M.; Xu, M.-D.; Yu, Z.-Y.; Tao, M. FOLFIRINOX regulated tumor immune microenvironment to extend the survival of patients with resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Gland. Surg. 2020, 9, 2125–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, H.; Wu, W.; Wang, B.; Cui, C.; Niu, J.; Chen, J.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Y. CXCL5 Plays a Promoting Role in Osteosarcoma Cell Migration and Invasion in Autocrine- and Paracrine-Dependent Manners. Oncol. Res. Featur. Preclin. Clin. Cancer Ther. 2017, 25, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonavita, O.; Massara, M.; Bonecchi, R. Chemokine regulation of neutrophil function in tumors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2016, 30, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaiber, U.; Hackert, T.; Neoptolemos, J.P. Adjuvant treatment for pancreatic cancer. Transl. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahan, L.; Phelip, J.M.; Le Malicot, K.; Williet, N.; Desrame, J.; Volet, J.; Petorin, C.; Malka, D.; Rebischung, C.; Aparicio, T.; et al. FOLFIRINOX until progression, FOLFIRINOX with maintenance treatment, or sequential treatment with gemcitabine and FOLFIRI.3 for first-line treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer: A randomized phase II trial (PRODIGE 35-PANOPTIMOX). J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamisawa, T.; et al. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet 2016, 388, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.J.; Goldstein, D.; Hamm, J.; Figer, A.; Hecht, J.R.; Gallinger, S.; Au, H.J.; Murawa, P.; Walde, D.; Wolff, R.A.; et al. Erlotinib Plus Gemcitabine Compared With Gemcitabine Alone in Patients With Advanced Pancreatic Cancer: A Phase III Trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 1960–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golan, T.; Hammel, P.; Reni, M.; Van Cutsem, E.; Macarulla, T.; Hall, M.J.; Park, J.-O.; Hochhauser, D.; Arnold, D.; Oh, D.-Y.; et al. Maintenance Olaparib for Germline BRCA-Mutated Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marabelle, A.; Le, D.T.; Ascierto, P.A.; Di Giacomo, A.M.; De Jesus-Acosta, A.; Delord, J.-P.; Geva, R.; Gottfried, M.; Penel, N.; Hansen, A.R.; et al. Efficacy of Pembrolizumab in Patients With Noncolorectal High Microsatellite Instability/Mismatch Repair–Deficient Cancer: Results From the Phase II KEYNOTE-158 Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, D.T.; Durham, J.N.; Smith, K.N.; Wang, H.; Bartlett, B.R.; Aulakh, L.K.; Lu, S.; Kemberling, H.; Wilt, C.; Luber, B.S.; et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science 2017, 357, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ott, P.A.; Bang, Y.-J.; Piha-Paul, S.A.; Razak, A.R.A.; Bennouna, J.; Soria, J.-C.; Rugo, H.S.; Cohen, R.B.; O’Neil, B.H.; Mehnert, J.M.; et al. T-Cell–Inflamed Gene-Expression Profile, Programmed Death Ligand 1 Expression, and Tumor Mutational Burden Predict Efficacy in Patients Treated With Pembrolizumab Across 20 Cancers: KEYNOTE-028. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karra, P.; Winn, M.; Pauleck, S.; Bulsiewicz-Jacobsen, A.; Peterson, L.; Coletta, A.; Doherty, J.; Ulrich, C.M.; Summers, S.A.; Gunter, M.; et al. Metabolic dysfunction and obesity-related cancer: Beyond obesity and metabolic syndrome. Obesity 2022, 30, 1323–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kandlakunta, H.; Nagpal, S.J.S.; Feng, Z.; Hoos, W.; Petersen, G.M.; Chari, S.T. Model to Determine Risk of Pancreatic Cancer in Patients With New-Onset Diabetes. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 730–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compound | Mechanism | Experimental model | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epicatechin and Quercetin (1:1 combination) | reductions in total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, total triglycerides, and fasting plasma glucose | randomized placebo-controlled trial | [108] |

| Curcumin | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidases, which leads to an increase in the activity of antioxidant enzymes | healthy horses (mixed breeds, mean age 6.2 ± 2.3) | [109,110] |

| Combination of swertiamarin and quercetin (CSQ) | activation of viable β-cells, reducing levels of total cholesterol, triglycerides, and LDL, while simultaneously increasing HDL | diabetic rats | [111] |

| Metformin | insulin or sulfonylureas | patients | [112,113] |

| Naringenin | upregulation of adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a key enzyme involved in cellular energy regulation. | [114] |

| Compound | Mechanism | Experimental model | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Naringenin | Increased Activity of ASK1, P38, P53, JNK, and Reactive Oxygen Species Gemcitabine's ability to prevent cancer drug resistance also limits tumor cell invasion. | SNU-213 cells AsPC-1, PANC-1 |

[130] [131] |

| Combination with naringenin | Effects that suppress cell proliferation, invasion, and p38 signaling | MIA PaCa-2, PANC-1, SNU-213, BALB/c nude mice |

[132]. |

| Metformin | Increased levels of manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) and decreased levels of NADPH oxidase 2 and 4 | MiaPaCa-2 and PANC-1 | [138] |

| QYHJ | Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1/NQO1 axis, p-PI3K/p-AKT/p-mTOR, and p-AKT/mTOR inhibition | PANC-1, MIA PaCa-2 | [137] |

| XLP | A reduction in the activity of MMP2, PTGS2, CASP9, IL4, and CTSD | Mouse PC Panc-02 cells Transfection pCDNA3.1(+)-PTGS2 and pCDNA3.1(+)-NC, Male C57BL/6 mice, 4–6 weeks old | [139,152] |

| Oxalidaceae | ERK/Src/STAT3 | BxPC3 | [140] |

| Thymoquinone | Increased p21 and p53; downregulation of Bcl-xL, Bcl-2, XIAP, Notch1, NICD, PTEN, Akt/mTOR/S6 Signaling; upregulation of caspases-3, -9, Bax, and cytochrome c; G2 cycle arrest and Sub G0/G1 arrest; | MiaPaCa-2, AsPC- 1 | [141,142,143,144]. |

| WOG | p53 expression was stimulated, and the Beclin-1/PI3K, Akt/ULK1/4E-BP1/CYLD, and mTOR pathways were all inhibited. | PANC-1, Colo-357, HPCCs4, Capan-1, Colo-357 |

[146] |

| WOG | Suppressing Mcl-1, CDK-9, c-FLIP, and MDM2 | Capan-1, Colo-357 | [146,147] |

| BBR | Release of cytochrome c and caspase 7 | BxPC-3, HPDE-E6E7c7 cells | [148] |

| Compound | Efficacy | Reference |

| Mistletoe (Viscum album L) |

Improve survival rates from the current 2.7 months to 4.8, | [156,158] |

| QYHJ | Improved 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival with no obvious side effects | [139] |

| Combination of Curcuminoids and Gemcitabine | Curcumin increases chemotherapy's efficacy | [159] |

| Curcuminoids | Health benefits, including fewer unwanted consequences, are increasing | [160,161,162] |

| Korean Red ginseng | Elevated CD4+ lymphocytes and a higher CD4+/CD8+ T lymphocyte counts | [168,169] [170] |

| Drug | Target | Characterization | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| FOLFIRINOX; Leucovorin (LV), 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU), Irinotecan, and Oxaliplatin | C-X-C motif chemokine 5 (CXCL5) | Influence on tumor immunity regulation | [177]. |

| Olaparib | BRCA1/2 mutations | [184]. | |

| Afatinib and MCLA-128 | PDAC drivers, which are characterized by the presence of wild-type KRAS, include ERBB inhibitors. | ERBB mutations | [12]. |

| larotrectinib and Entrectinib | PDAC drivers include TRK inhibitors, which are activated by the presence of wild-type KRAS. | TRK mutations | [12]. |

| Crizotinib | PDAC drivers with wild-type KRAS include sensitivity to ALK/ROS inhibitors. | ALK/ROS mutations | [12]. |

| AMG510 | KRASG12C mutation | [12]. | |

| Pembrolizumab | Programmed cell death protein (PD-1) inhibitor | Microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) | [171,185]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).