1. Introduction

Aberrations during embryological development of pancreas can result in various anatomic variations of pancreas and pancreatic duct including variations in either course of pancreatic duct like descending, vertical, loop or sigmoid course or configuration of the pancreatic duct like bifid configuration with dominant duct of Wirsung, dominant duct of Santorini without divisum, absent duct of Santorini and Ansa Pancreatica, anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal junction, pancreas divisum, annular pancreas, ectopic pancreas, pancreatic agenesis and hypoplasia of the dorsal pancreas and accessory pancreas.1 Majority of these developmental anomalies do not have clinical significance and are incidentally detected during cross sectional imaging or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Improvement in cross sectional imaging techniques especially development of high resolution magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) have improved our diagnostic ability to non-invasively diagnose pancreatic ductal as well as parenchymal anomalies.2 Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) also provide high resolution images of pancreas as well as pancreatic duct and has excellent accuracy for diagnosis of various pancreatic parenchymal as well as ductal anomalies.3 In this review article, we will focus on the role of EUS in diagnosis of various pancreatic duct anomalies.

2. Embryological development of Pancreas

Proper understanding of various congenital pancreatic anomalies requires in depth understanding of its embryological development. The development of pancreas during embryogenesis starts during the 5th week with the development of two buds, a larger dorsal bud, and the smaller ventral bud, from the second part of the duodenum. The ventral bud arises from the ventral outpouching of the gut that also forms liver, cystic duct, gall bladder, bile duct and therefore, common bile duct (CBD) and the ventral pancreatic duct share common embryonic origin. The dorsal bud after arising from the endoderm, starts growing towards left lateral direction and by sixth week, it enters the dorsal mesentery to become intraperitoneal. The smaller ventral bud arises from the hepatic diverticulum and under the effect of a complex interaction between epithelium and the mesenchyme, the ventral bud migrates with the bile duct and rotates clockwise around the duodenum to fuse with the dorsal bud by seventh embryonic week.4-6

Afterwards, due to further growth of the foregut, ventral bud and bile duct rotates counter-clockwise along duodenum and take a dorsal position and pancreas grows as one organ with joining of bile duct with pancreatic duct. Pancreatic ductal system starts developing once ventral and dorsal part fuse together side-by-side. Larger dorsal bud, ultimately, leads to formation of neck, body, and tail of pancreas, whereas, smaller ventral bud forms head and uncinate process. The duct of the dorsal duct, also known as the duct of Santorini (accessory pancreatic duct), drains into the minor papilla. Similarly, a new duct connects the distal part of the dorsal duct with the shorter duct of the ventral pancreas leading to formation of the main pancreatic duct (the duct of Wirsung) which drains into the major papilla. Accessory pancreatic duct joins the main pancreatic duct about 1-2 cm proximal to the ventral duct or at the distal end of the ventral duct. The part of the accessory pancreatic duct, distal to the union of the two ducts becomes stenotic and may become obliterated, thus functionally playing little role in drainage of pancreatic exocrine secretion which preferentially flows through the main pancreatic duct.6-8

3. Types of pancreatic duct anomalies

Physiologically, developmental anomalies of pancreas can be broadly divided into i) fusion anomalies, ii) migration anomalies and iii) duplication anomalies (

Table 1). The pancreatic duct can also have variations with respect to its course, configuration, anomalous union, and pancreas divisum (

Table 2).

4. Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS) in Pancreatic Diseases

EUS has revolutionised the diagnosis and management of pancreatic diseases. The superiority of EUS over other imaging modalities is due to its ability to provide high resolution images of both the pancreatic parenchyma as well as the pancreatic duct. EUS is the investigation of choice for etiological evaluation in idiopathic pancreatitis as well as for early diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis.9-11 By virtue of its ability to provide high resolution images of the pancreatic duct, EUS can also help in accurate diagnosis of various congenital pancreatic ductal anomalies. Along with the visualisation of the course and configuration of the pancreatic duct, EUS can also visualise changes in the pancreatic parenchyma thereby helping in early diagnosis of any co-existent pancreatic disease.

5. Pancreas divisum

Pancreas divisum is the most common type of anatomical anomaly of the pancreatic duct which results from failed or abnormal fusion of the ventral and the dorsal pancreatic duct. This results in preferential drainage of the pancreatic secretion by the duct of Santorini into the minor papilla covering body and tail region of the pancreas whereas the duct of Wirsung plays a marginal role in drainage into the major papilla.12 The frequency of pancreas divisum has been variably reported with autopsy series reporting frequency varying between 4.4 and 12% and ERCP studies reporting frequency varying between 0.3–8 %.13

The clinical significance of pancreas divisum is controversial because of conflicting evidence. Majority of patients with pancreas divisum have no pancreatic symptoms throughout their life and therefore it is suggested that this anatomical variant has little or no clinical significance.14, 15 However, few studies have demonstrated increased frequency of pancreas divisum in patients with idiopathic pancreatitis suggesting its pathogenic role.13, 16, 17 Relief of pain following minor papilla sphincterotomy suggests that the minor papilla orifice in these symptomatic patients is critically narrowed resulting in impaired outflow of pancreatic juice and increased intraductal pressure resulting in abdominal pain and pancreatitis.18 However, this “obstructive pancreatopathy” concept has been challenged by recent genetic studies that have suggested that cystic fibrosis trans-membrane conductance regulator (CFTR) or other unidentified genetic mutations predisposes pancreas divisum patients to recurrent acute or chronic pancreatitis rather than impaired pancreatic drainage.19, 20 The debate about its exact pathogenic role continues but few patients with symptomatic pancreas divisum do get relief following successful endotherapy.

Pancreas divisum has been classified into three types based upon the anatomy of the ductal system. Type 1 is when the dorsal and ventral system are completely separated; type 2 is when the ventral duct is completely absent; type 3 is when there is a rudimentary duct connecting the dorsal and the ventral ductal system. Complete divisum implies lack of fusion between the dorsal and the ventral duct (Type 1), whereas in incomplete divisum there is a rudimentary channel between the dorsal and the ventral duct, as in type 3. Clinically, complete and incomplete divisum have similar behaviour.21, 22

Pancreas divisum can be associated with cystic dilatation of the dorsal pancreatic duct at the junction with the minor papilla. This is known as Santorinocoele and is hypothesized to occur due to stenosed minor papilla along with the weakness of the ductal wall. Apart from Santorinocoele, dilated dorsal duct can be seen in chronic pancreatitis, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) and ductal adenocarcinoma.23-25

Pancreatic pseudodivisum or ‘false pancreas divisum’ is an entity described in literature where there is an acquired defect observed on pancreatogram resulting from blockade of ventral pancreatic duct by malignancy, stricture (as in chronic pancreatitis) or mucous plug, in the presence of normal fusion between ventral and the dorsal duct. Usually, it is seen in older males with prolonged history of alcohol use, unlike pancreas divisum which is seen in young females.26

6. Endoscopic ultrasound features of pancreas divisum: radial and linear EUS

Pancreas divisum can be diagnosed by radial as well as linear echoendoscope. EUS features that suggest presence of pancreas divisum include /absence or lack of delineation of ‘stack sign’, presence of ‘cross-duct sign’, and inability to trace the main pancreatic duct till the body starting from the major duodenal papilla (

Table 3).

12 Here, we will first discuss, in brief, about the conventional techniques of EUS and findings with respect to the pancreatic duct followed by the findings that helps to make diagnosis of pancreas divisum.

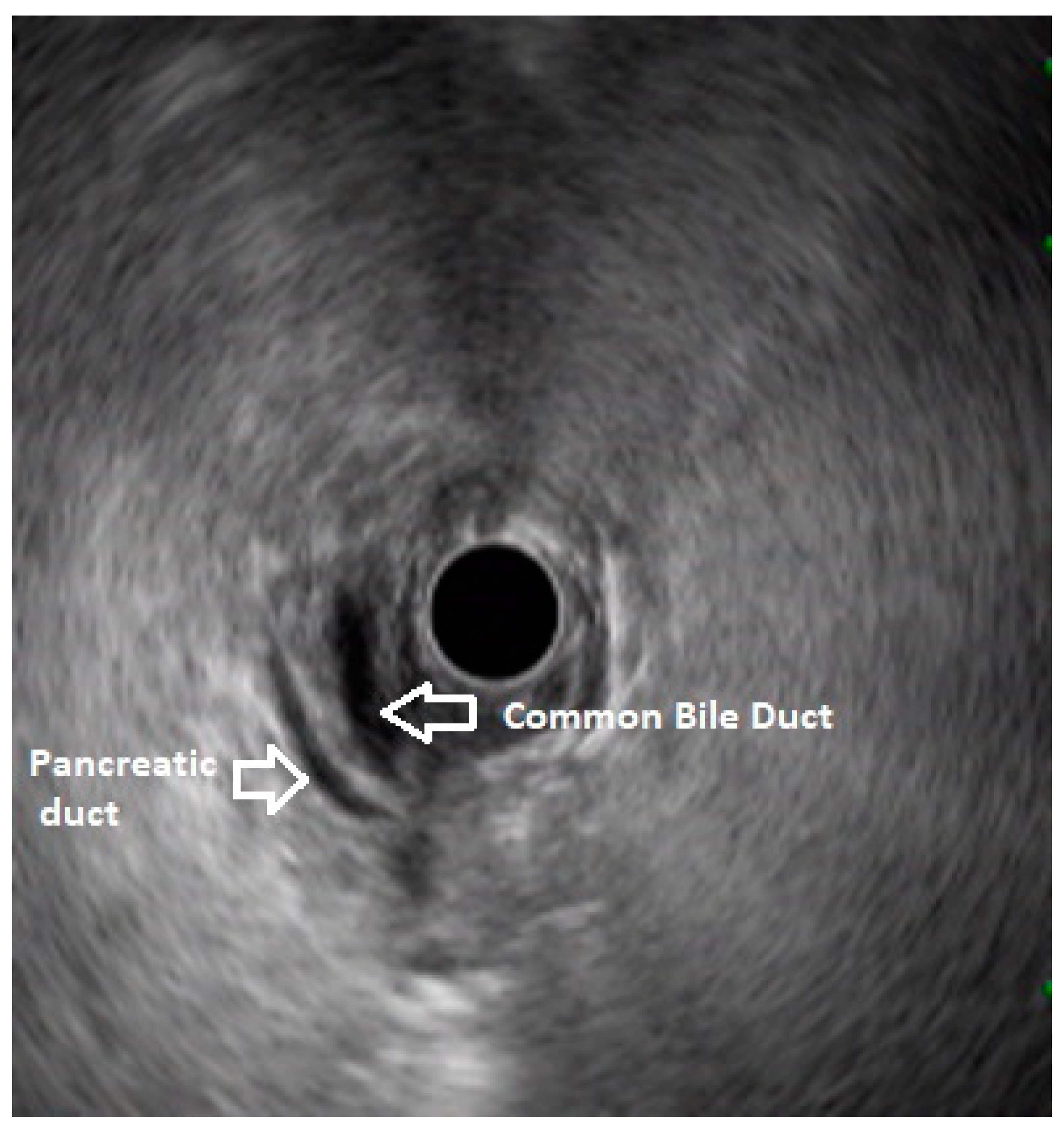

In routine endosonographic examination, all parts of the pancreas are comprehensively examined when seen from three stations, that are the apex of the duodenal bulb, papilla and distal to the papilla. Among these, the best position is the apex of the duodenal bulb as it brings the major portion of the head of pancreas, distal common bile duct and the portal vein in the same frame. For positioning, the EUS scope is advanced along the greater curvature of the stomach and when pylorus is visible, the tip of the scope is negotiated through it followed by air insufflation of the duodenal bulb. This is followed by gentle downward deflection of the tip of the scope making the duodenal bulb visible. Doppler imaging helps differentiating bile duct from the arteries (hepatic artery and the gastroduodenal artery) and portal vein. At this point, the endosonologist gets the view of distal CBD, pancreatic duct, and the portal vein in a single frame in which one structure appears to lie on top of the other and this is called as the ‘stack sign’ (

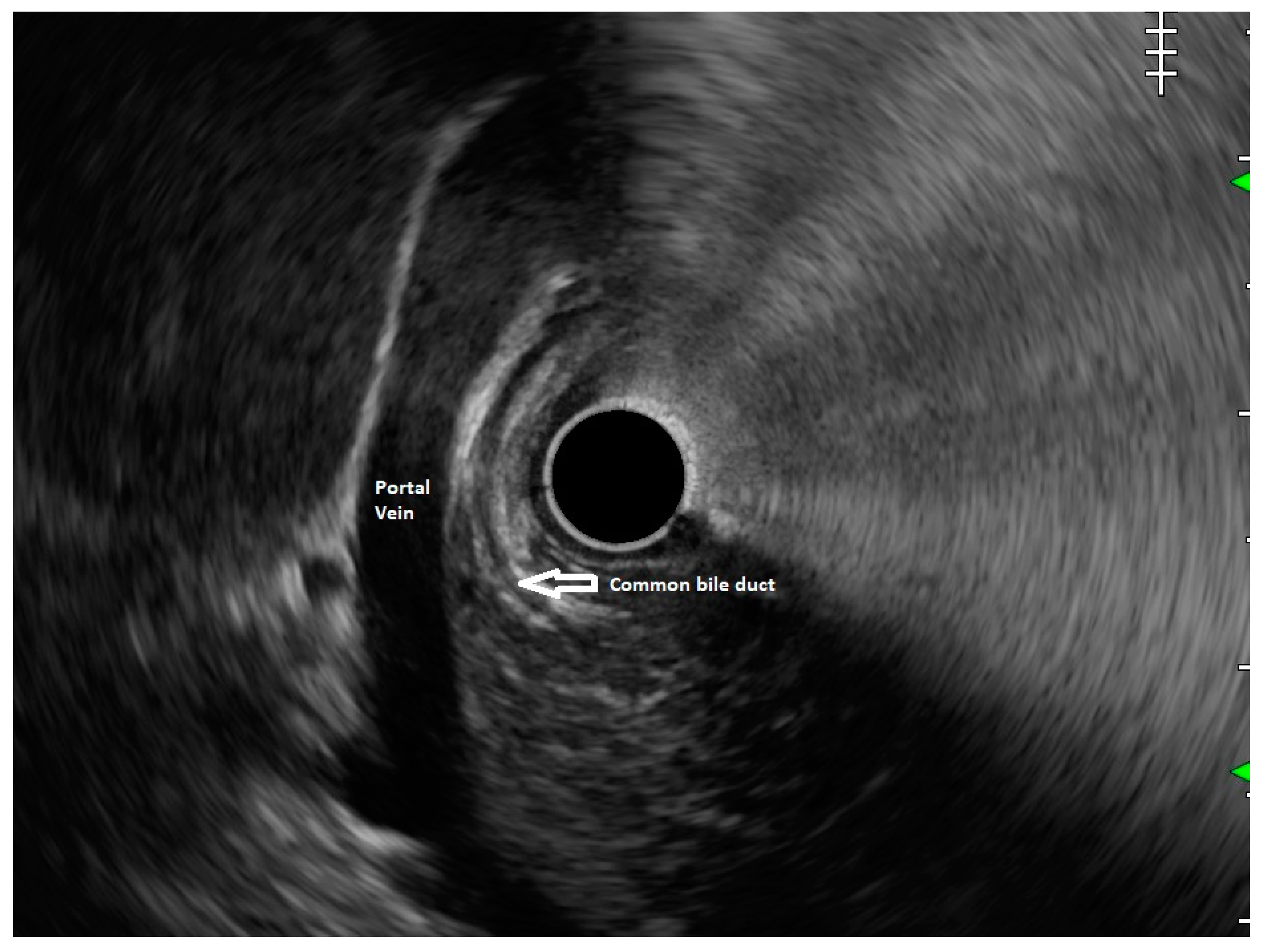

Figure 1) and absence of stack sign suggests possibility of pancreas divisum (

Figure 2). As these structures do not lie in the same plane, various manoeuvres like clockwise and counter clockwise rotation and right and left torque are required for a detailed examination of these structures.

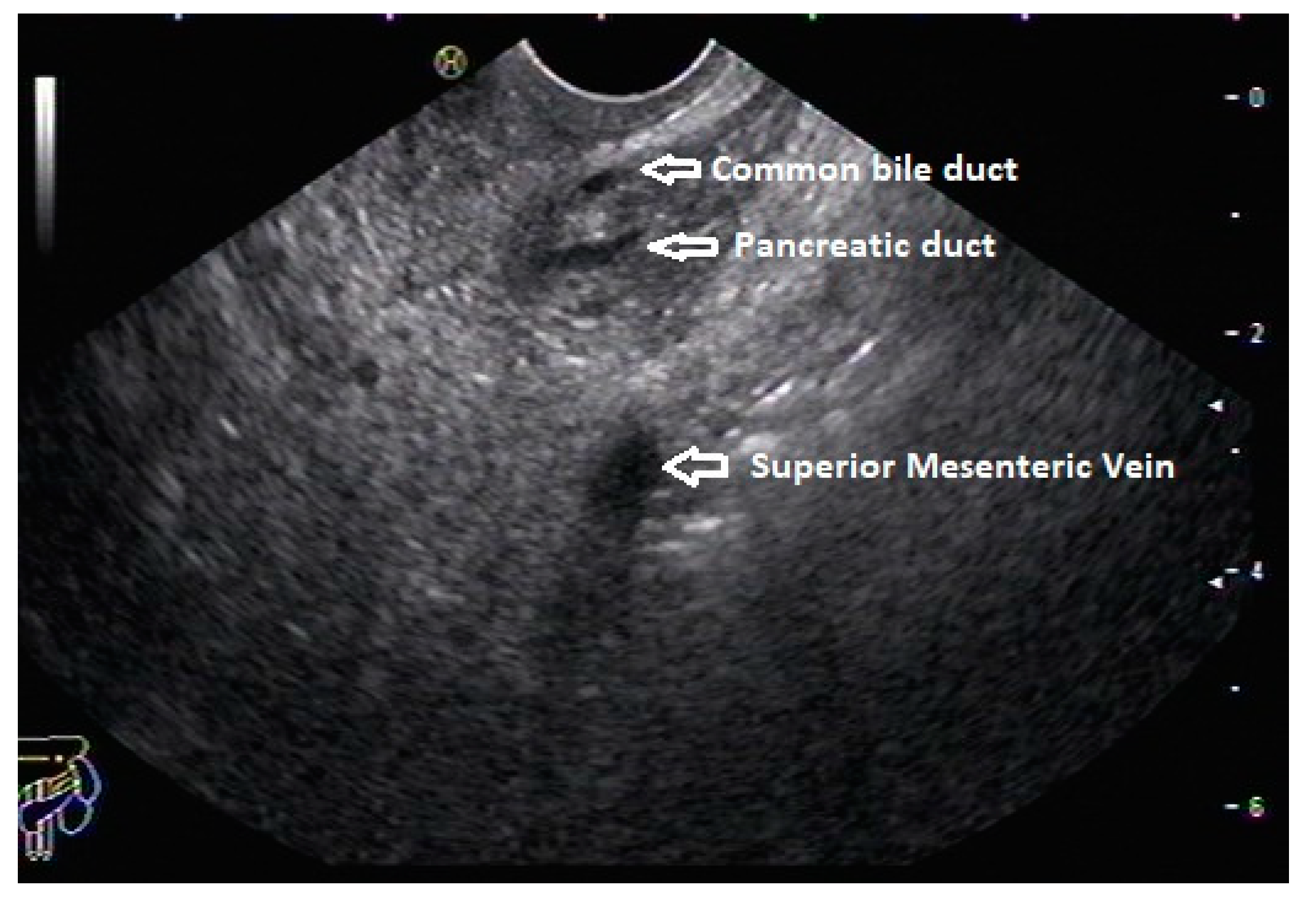

12 Although this sign is conventionally described in radial EUS, linear EUS can also detect similar anatomical configuration although there are some subtle differences in linear EUS. In linear EUS, usually the ‘stack’ consists of distal CBD and pancreatic duct which are seen on parallel axis (portal vein is not seen). However, superior mesenteric vein (SMV) or artery (SMA) can be seen on linear EUS in a different axis once a clockwise rotation is performed and origin of portal vein from the SMV can also be easily demonstrated (

Figure 3).

27

‘Crossed-duct sign,’ which is also described in MRCP, has been conventionally described in radial EUS. In patients with pancreas divisum, while examining from the duodenal bulb and gradually withdrawing the scope towards the minor papilla, the dorsal duct can be seen crossing the CBD when viewed from the duodenal bulb.27 In linear EUS, the course of the pancreatic duct can be traced from the papilla and duct of Wirsung and duct of Santorini can be traced backwards from major and minor duodenal papilla respectively. In pancreas divisum, minor papilla can easily be identified (may appear dilated sometime) due to the prominent duct of Santorini. Identification of a more dilated dorsal duct compared to the ventral duct is another ancillary finding which reinforce the diagnosis especially after secretin injection.

In about three fourth of normal population, a distinction between dorsal and ventral pancreas can be identified on EUS as the ventral part (often termed as the ventral analge), appear hypoechoic and dorsal part appear hyperechoic (brighter) with a characteristic border at the interface. This is also known as the ventral-dorsal transition. In pancreas divisum, the ventral pancreatic duct does not cross this border as there is fusion failure. Thus, tracing the pancreatic duct crossing this transition border rules out pancreas divisum.

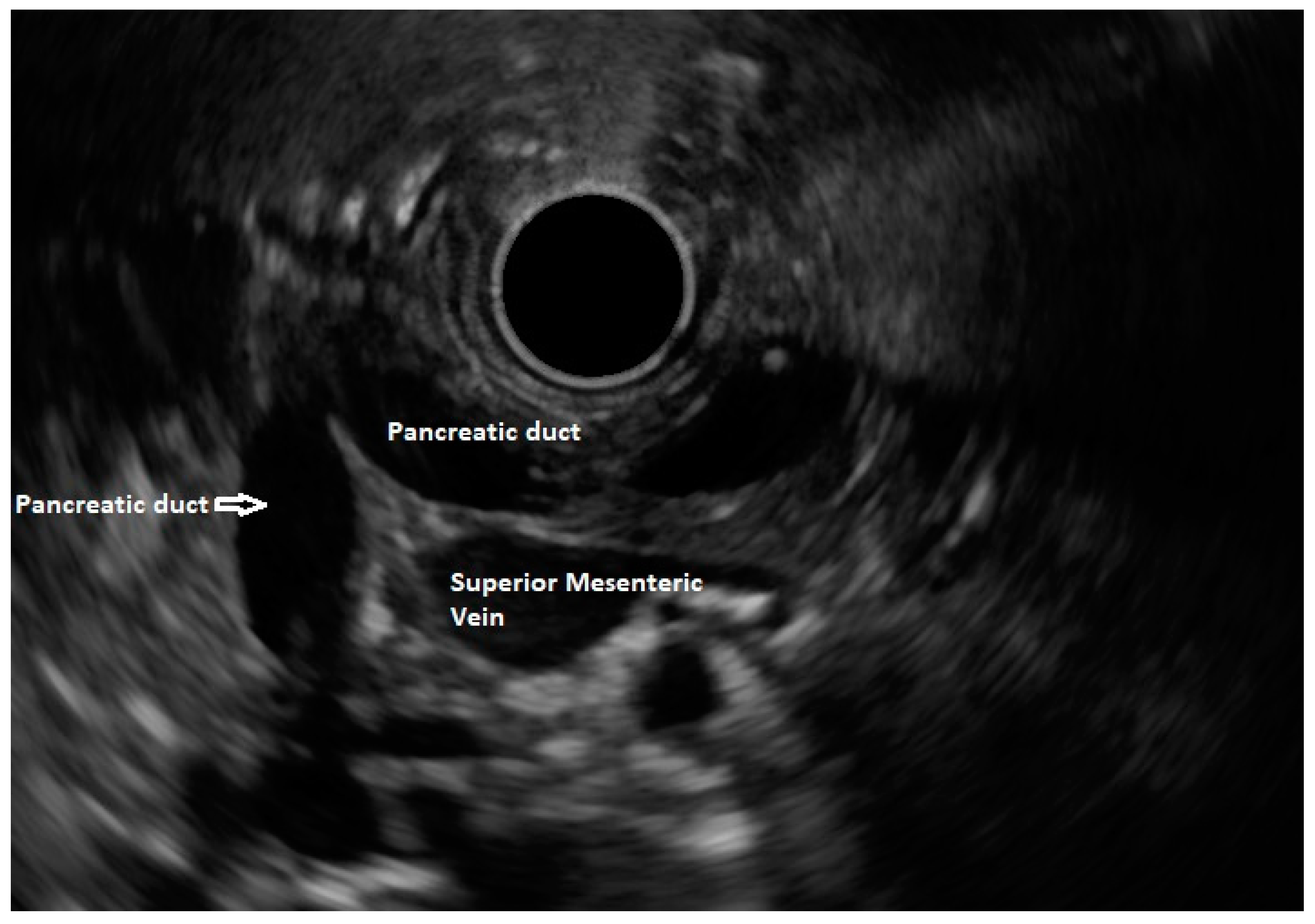

27 The diagnosis of pancreas divisum can be excluded if the pancreatic duct can be traced from the major papilla to the pancreatic body or dipping at the genu towards the major papilla when seen from the stomach (

Figure 4).

28

On linear EUS, pancreas divisum can be demonstrated from three stations with different findings as follows: I) when the scope is in duodenal bulb, dorsal pancreatic duct can be visualized closer to the duodenal wall, above the CBD (The dorsal duct can be seen emerging from the minor papilla and coursing through the hyperechoic dorsal pancreas, which remain within the same plus an identifiable point of crossing the CBD) II) From the stomach, the same finding can be demonstrated. III) When seen from the descending duodenum, main pancreatic duct is not identified and the ventral duct appear short and ending abruptly within the hypoechoic ventral part, giving rise to suspicion of pancreas divisum.

7. Diagnostic accuracy for diagnosis of Pancreas Divisum by EUS

Various criteria have been applied while evaluating cases of pancreas divisum with radial and linear EUS. In a study by Bhutani et al, investigators tried to obtain stack sign in patients with pancreas divisum (n=6) and compared them to control (n=30), and found significantly lower percentage of patient with pancreas divisum having demonstrable stack sign compared to controls (33% vs 83.3%, p=0.04).29 False positive stack sign was found in 2 patients. The accuracy and positive predictive value of the test was found to be 80%. In a study by Rana et al, two criteria were evaluated viz., absence of stack sign, and ability to trace the duct backwards from the papilla.28 In this study, authors had found that sensitivity and specificity of these two criteria were 50%, 97% and 100%, 96% respectively. In the former study, EUS was done after diagnostic ERCP and the endosonologist was aware of the diagnosis (which can have led to bias), whereas in the latter study, EUS was done prior to ERCP. Both studies, used 7.5 MHz radial EUS for diagnosis.

Tandon et al went beyond the mere absence of stack sign to improve specificity of the EUS criteria.30 They used two criteria for diagnosing pancreas divisum, I) visualization of bile duct and the pancreatic duct entering the second part of the duodenum, II) pancreatic duct traversing the duodenal wall anteriorly and proximal to the bile duct. Using these criteria, authors prospectively diagnosed two out of three cases of pancreas divisum without any false positive diagnosis.

Lai et al studied 162 patients with linear EUS who subsequently also underwent ERCP.31 They prospectively evaluated these patients using the ‘trace-back’ sign and the ‘V-D transition’ sign and absence of any one of these signs was considered to be diagnostic for pancreas divisum. They found the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and accuracy of EUS for diagnosis of pancreas divisum to be 95%,97%, 86%,99% and 97% respectively.

8. Comparison of EUS vs MRCP for diagnosis of Pancreas Divisum

A systematic review and meta-analysis attempted to compare the diagnostic accuracies of MRCP, secretin-MRCP and EUS for diagnosis of pancreas divisum.

32 The authors included 10 studies with 856 patients evaluated with MRCP, 5 studies with 625 patients evaluated with secretin-MRCP and 7 studies of 470 patients evaluated with EUS. They reported that EUS is more reliable than MRCP for diagnosis of pancreas divisum, but is inferior to secretin-MRCP. In terms of the effect of diagnostic test, EUS performed better than MRCP, but was found to be slightly inferior to secretin-MRCP (

Table 4).

9. Role of secretin enhanced EUS and EUS elastography in Pancreas divisum

Successful and accurate detection of pancreas divisum on EUS is influenced by multiple factors like expertise of the endosonologist and presence of dilated pancreatic duct. Use of intravenous secretin has been used in EUS to make the pancreatic duct more prominent and thus improve the sensitivity of EUS for diagnosis of pancreas divisum. In ERCP based studies, it has been shown that secretin increases intraductal pressure within 1 minutes of administration with peak effect on the pancreatic duct occurring within 3 to 5 minutes of administration.33 Secretin has been shown to improve the visualisation of the pancreatic duct and thus increases sensitivity for diagnosis of pancreas divisum.34

Secretin EUS has also been used to predict response to endoscopic minor papillotomy. Catalano et al studied 40 patients with pancreatitis and pancreas divisum and they reported that 81% patients with abnormal secretin EUS test had response to endotherapy whereas only 17% of patients with abnormal secretin EUS had failed endotherapy (p=0.02). An abnormal secretin EUS test was defined as an increase in duct diameter by 1mm or more following secretin injection and the dilatation remaining at least for 1 mm throughout the 15 minute test.35

EUS elastography is an imaging modality that evaluates the stiffness of the tissues and has been shown to be useful in evaluation of chronic pancreatitis as well as in differentiating various pancreatic masses.36 In pancreas divisum, role of EUS elastography is not well-defined. However, due to difference in echogenicity as well as stiffness of ventral and dorsal pancreas, EUS elastography can be useful in detecting ventral-dorsal transition which helps in diagnosis of pancreas divisum.27

10. Other pancreatic duct anomalies: Ansa pancreatica, anomalous pancreatobiliary union (APBU) and role of EUS

Ansa pancreatica is one of the least common anomalies of the pancreatic duct which is characterised by the absence of accessory pancreatic duct and presence of an ‘S’-shaped branch arising from the main duct which ultimately drains into the minor papilla.36 It is different from “meandering pancreatic duct” where there is a looping of the distal part of the main duct which joins patent duct of Santorini. It can be diagnosed with MRCP, ERCP or EUS. There are only anecdotal reports of ansa pancreatica being diagnosed with EUS.37 Due to rarity of the disease, there is no data available to show superiority of any diagnostic modality over other.

Anomalous bilio-pancreatic union (ABPU) is another uncommon anomaly of the pancreatic duct with a prevalence of 1.5-3.2%.38 It is characterised by abnormal union of pancreatic duct and common bile duct above the sphincter of Oddi, outside the duodenal wall. Multiple associations have been described in literature which include choledochal cysts, carcinoma of gall bladder, cholangiocarcinoma, chronic pancreatitis, and recurrent acute pancreatitis. There have been multiple proposed mechanisms for pancreatitis in ABPU which include biliopancreatic reflux, stenosis of the long common channel, obstruction of the channel by stones, epithelial hyperplasia, protein plug, intraductal hypertension. MRCP and ERCP can identify ABPU although the latter is used with therapeutic intent only (pancreatic or biliary drainage. EUS has also been used to identify ABPU and the EUS criteria suggestive of ABPU is union of bile and pancreatic duct outside the duodenal wall. Ko et al reported that EUS detected 91% of patients with ABPU on EUS.39 Although EUS can potentially be used for diagnosis of various rare congenital pancreatic anomalies, there is no clear consensus on preference. However, taking into consideration the high diagnostic yield of EUS in recurrent or chronic pancreatitis and acute pancreatitis patients of unclear aetiology, EUS is likely to be helpful in establishing the diagnosis of these pancreatic duct malformations.

11. EUS in Annular Pancreas

Annular pancreas (AP) is a rare congenital anomaly that results from a failure of the ventral anlage to rotate clockwise with the duodenum during the embryogenesis resulting in a thin band of pancreatic parenchyma encircling either completely or partially the second part of the duodenum near the major papilla.40 The patients with annular pancreas may remain asymptomatic or present with pancreatitis, duodenal outlet obstruction, gastrointestinal bleeding or abdominal pain alone. It is generally symptomatic in children especially neonates and in adults it is usually an incidental finding on imaging.

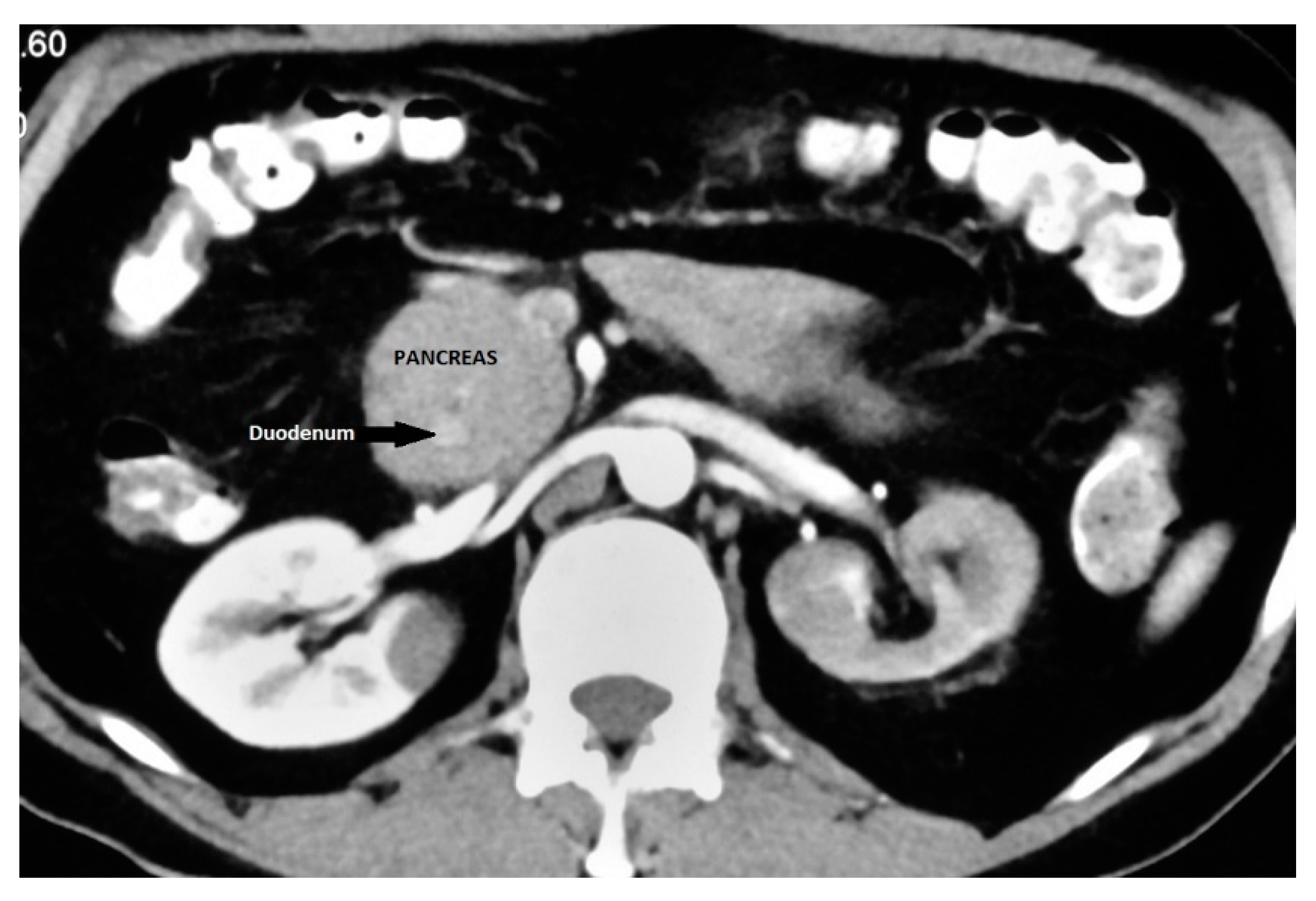

It is an important differential diagnosis for descending duodenal obstruction and contrast enhanced CT can demonstrate the enhancing pancreatic tissue around the duodenum (

Figure 5).

41 ERCP is considered as the gold standard for diagnosis of AP as it provides visualization of the descending duodenum and the pancreatic ductal system along with major and minor papilla.

42, 43 Duodenal narrowing is usually located just proximal to the major papilla and the minor papilla is usually situated at the proximal rim of the annular ring. In majority of patients, the duct of the annular pancreas communicates with the main pancreatic duct arising from the major papilla. However, ERCP via the major papilla will not be able to diagnose AP in patients where the annular duct opens into the minor papilla or directly into the duodenum.

44 Moreover, ERCP is technically difficult in patients with significant duodenal obstruction. The annular duct can also be detected on MRCP where it commonly connects with main pancreatic duct near the major papilla but also may drain into the dorsal duct near the minor papilla or directly drain into the duodenum.

45 MRCP, apart from being non-invasive and operator independent, can also visualise pancreatic parenchyma around the duodenum.

EUS is not a primary imaging modality for the diagnosis of AP but is an useful investigational modality for elucidating the cause of extrinsic compression of the duodenum. Like MRCP, EUS can delineate both the pancreatic parenchyma as well as the pancreatic duct around the duodenum (

Figure 6) and thus help in accurate diagnosis of AP. Even in patients with duodenal obstruction, EUS can help in diagnosis of AP by scanning from the duodenal bulb.

44 An added advantage of EUS is that it can help in diagnosis of coexistent pancreatic pathologies like chronic pancreatitis and ductal calculi.

46 Papachristou et al studied 5 patients of AP with radial EUS and reported that CT could detect AP in only 1/5 patients whereas EUS could detect AP in all 5 patients.

46 EUS detected an encircling band of pancreatic tissue by approximately 360° in 3, 270° in 1 and 180° in 1 patient respectively and within this band of encircling tissue the pancreatic duct was identified in 4 of 5 patients. The authors suggested following technical manoeuvres during radial EUS to facilitate identification of encircling pancreatic tissue:

a). use of glucagon to inhibit gut motility

b). minimal balloon inflation to help avoid rapid uncontrolled scope withdrawal

c). gentle scope deflection

d). gentle forward pressure with an overinflated balloon into the narrowed region of the duodenum

12. Conclusions

EUS provides high resolution images of both the pancreatic parenchyma as well as the pancreatic duct and therefore is an ideal imaging modality for diagnosis of various pancreatic duct anomalies. Studies have reported high accuracy of EUS for diagnosis of various pancreatic duct anomalies like pancreas divisum, APBU and AP. Use of secretin to improve the visualization of the pancreatic duct can improve the diagnostic capability of EUS to diagnose various congenital pancreatic duct anomalies. Ability to diagnose various co-existent pancreatic pathologies along with congenital duct anomalies is an added advantage of EUS. Being an operator dependent imaging modality, and presence of multiple EUS criteria for diagnosis of various pancreatic duct anomalies varying in sensitivity and specificity are important limitations of EUS. Further prospective comparative studies are required to establish accurate EUS diagnostic criteria for diagnosis of various pancreatic duct anomalies and its exact role in diagnostic algorithm for evaluation of patients with suspected pancreatic duct anomalies.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest and no financial disclosures to be made by any of the authors.

Abhirup Chatterjee: None

Surinder Singh Rana: None

References

- Türkvatan, A.; Erden, A.; Türkoğlu, M.A.; et al. Congenital variants and anomalies of the pancreas and pancreatic duct: Imaging by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreaticography and multidetector computed tomography. Korean J Radiol 2013, 14, 905–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leyendecker, J.R.; Elsayes, K.M.; Gratz, B.I.; et al. MR cholangiopancreatography: Spectrum of pancreatic duct abnormalities. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2002, 179, 1465–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, S.S. Evaluating the role of endoscopic ultrasound in pancreatitis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022, 16, 953–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghei, P.; Sokhandon, F.; Shirkhoda, A.; et al. Anomalies, anatomic variants, and sources of diagnostic pitfalls in pancreatic imaging. Radiology 2013, 266, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covantsev, S.; Chicu, C.; Mazuruc, N.; et al. Pancreatic ductal anatomy: More than meets the eye. Surg Radiol Anat 2022, 44, 1231–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadokoro, H.; Takase, M.; Nobukawa, B. Development and congenital anomalies of the pancreas. Anat Res Int 2011, 2011, 351217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, R.J.; Szucs, R.A.; Turner, M.A. Congenital abnormalities of the pancreas and biliary tree in adults. Radiographics 1995, 15, 49–68, quiz 147-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villasenor, A.; Stainier, D.Y.R. On the development of the hepatopancreatic ductal system. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2017, 66, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.S.; Bhasin, D.K.; Rao, C.; et al. Role of endoscopic ultrasound in idiopathic acute pancreatitis with negative ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. Ann Gastroenterol 2012, 25, 133–137. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, J.; Ouyang, Y.; Yu, C.; et al. Comparison of EUS with MRCP in idiopathic acute pancreatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc 2018, 87, 1180–1188e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.S.; Vilmann, P. Endoscopic ultrasound features of chronic pancreatitis: A pictorial review. Endosc Ultrasound 2015, 4, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, S.S.; Gonen, C.; Vilmann, P. Endoscopic ultrasound and pancreas divisum. Jop 2012, 13, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, S.D.; Affronti, J.P. Pancreas divisum, an evidence-based review: Part I, pathophysiology. Gastrointest Endosc 2004, 60, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spicak, J.; Poulova, P.; Plucnarova, J.; et al. Pancreas divisum does not modify the natural course of chronic pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol 2007, 42, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayakawa, T.; Kondo, T.; Shibata, T.; et al. Pancreas divisum. A predisposing factor to pancreatitis? Int J Pancreatol 1989, 5, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Gao, R.; Wang, W.; et al. A systematic review on endoscopic detection rate, endotherapy, and surgery for pancreas divisum. Endoscopy 2009, 41, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.K.; Abu-El-Haija, M.; Nathan, J.D.; et al. Pancreas Divisum in Pediatric Acute Recurrent and Chronic Pancreatitis: Report From INSPPIRE. J Clin Gastroenterol 2019, 53, e232–e238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogel, E.L.; Toth, T.G.; Lehman, G.A.; et al. Does endoscopic therapy favorably affect the outcome of patients who have recurrent acute pancreatitis and pancreas divisum? Pancreas 2007, 34, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudari, C.P.; Imperiale, T.F.; Sherman, S.; et al. Risk of pancreatitis with mutation of the cystic fibrosis gene. Am J Gastroenterol 2004, 99, 1358–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelrud, A.; Sheth, S.; Banerjee, S.; et al. Analysis of cystic fibrosis gener product (CFTR) function in patients with pancreas divisum and recurrent acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2004, 99, 1557–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamisawa, T.; Tu, Y.; Egawa, N.; et al. Clinical implications of incomplete pancreas divisum. Jop 2006, 7, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.H.; Lee, S.S.; Kim, C.D.; et al. Incomplete pancreas divisum: Is it merely a normal anatomic variant without clinical implications? Endoscopy 2001, 33, 778–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takuma, K.; Kamisawa, T.; Tabata, T.; et al. Pancreatic diseases associated with pancreas divisum. Dig Surg 2010, 27, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoyama, N.; Taniguchi, Y.; Wada, M.; et al. A case of pancreas divisum with marked dilatation of dorsal pancreatic duct. Clin J Gastroenterol 2022, 15, 1204–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boninsegna, E.; Manfredi, R.; Ventriglia, A.; et al. Santorinicele: Secretin-enhanced magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography findings before and after minor papilla sphincterotomy. Eur Radiol 2015, 25, 2437–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhaliwal, H.S.; Shah, C.; Hasan, M.K. A Rare Case of Pancreas Pseudodivisum. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015, 13, e135–e136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Pathak, A.; Rameshbabu, C.S.; et al. Imaging of pancreas divisum by linear-array endoscopic ultrasonography. Endosc Ultrasound 2016, 5, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.S.; Bhasin, D.K.; Sharma, V.; et al. Role of endoscopic ultrasound in the diagnosis of pancreas divisum. Endosc Ultrasound 2013, 2, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutani, M.S.; Hoffman, B.J.; Hawes, R.H. Diagnosis of pancreas divisum by endoscopic ultrasonography. Endoscopy 1999, 31, 167–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, M.; Topazian, M. Endoscopic ultrasound in idiopathic acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2001, 96, 705–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, R.; Freeman, M.L.; Cass, O.W.; et al. Accurate diagnosis of pancreas divisum by linear-array endoscopic ultrasonography. Endoscopy 2004, 36, 705–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Munker, S.; Zhou, B.; et al. The Accuracies of Diagnosing Pancreas Divisum by Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography and Endoscopic Ultrasound: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 35389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamokova, B.; Bastati, N.; Poetter-Lang, S.; et al. The clinical value of secretin-enhanced MRCP in the functional and morphological assessment of pancreatic diseases. Br J Radiol 2018, 91, 20170677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Dillman, J.R.; Anton, C.G.; et al. Secretin Improves Visualization of Nondilated Pancreatic Ducts in Children Undergoing MRCP. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2020, 214, 917–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catalano, M.F.; Lahoti, S.; Alcocer, E.; et al. Dynamic imaging of the pancreas using real-time endoscopic ultrasonography with secretin stimulation. Gastrointest Endosc 1998, 48, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Garcia, J.; Lindkvist, B.; Lariño-Noia, J.; et al. Endoscopic ultrasound elastography. Endosc Ultrasound 2012, 1, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaikh, D.H.; Alemam, A.; von Ende, J.; et al. Ansa Pancreatica, an Uncommon Cause of Acute, Recurrent Pancreatitis. Case Rep Gastroenterol 2021, 15, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherifi, F.; Bexheti, S.; Gashi, Z.; et al. Anatomic Variations of Pancreaticobiliary Union. Open Access Maced J Med Sci 2018, 6, 988–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, B.M.; Cha, S.W.; Kim, Y.S.; et al. Endosonography (EUS) for Detection of Anomalous Union of the Pancreaticobiliary Duct (AUPBD) in Patients with Asymptomatic Gallbladder Wall Thickening. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 2004, 59, P226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papachristou, G.I.; Topazian, M.D.; Gleeson, F.C.; et al. EUS features of annular pancreas (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2007, 65, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadvar, H.; Mindelzun, R.E. Annular pancreas in adults: Imaging features in seven patients. Abdom Imaging 1999, 24, 174–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmsathaphorn, K.; Burrell, M.; Dobbins, J. Diagnosis of annular pancreas with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Gastroenterology 1979, 77, 1109–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gromski, M.A.; Lehman, G.A.; Zyromski, N.J.; et al. Annular pancreas: Endoscopic and pancreatographic findings from a tertiary referral ERCP center. Gastrointest Endosc 2019, 89, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandpal, H.; Bhatia, V.; Garg, P.; et al. Annular pancreas in an adult patient: Diagnosis with endoscopic ultrasonography and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. Singapore Med J 2009, 50, e29–e31. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.Y.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Annular pancreas: Emphasis on magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2004, 28, 528–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gress, F.; Yiengpruksawan, A.; Sherman, S.; et al. Diagnosis of annular pancreas by endoscopic ultrasound. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 1996, 44, 485–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).