1. Introduction and Objectives

Canada is faced with an increasing risk of drought and excess precipitation in a warming climate (e.g., Tam et al. 2019, Bonsal et al. 2020, Zhang et al. 2019). Within Canada, the Prairie region stands out as a hotspot for both droughts and pluvials and therefore is associated with significant risks from these disasters. For example, a recent natural hazard assessment for Saskatchewan found that droughts and convective summer storms had the highest aggregate risk levels (Wittrock et al. 2018). The Prairies have more exposure to these extremes because of the high variability of precipitation in both time and space (Bonsal and Wheaton 2005). Often, periods and areas of drought and excess moisture occur in close proximity. Since hydroclimatic extremes are projected to occur with greater frequencies and intensities in a warming climate, more compound occurrences can be expected.

The selected study area for this paper includes Canada’s major agricultural region within the provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba, termed Prairies here. In this region, droughts cause considerable damage to ecosystems, the economy, human health, and society. Drought can be defined as a prolonged period of abnormally dry weather that depletes water resources for human and environmental needs (AES Drought Study Group, 1986). More specific definitions depend on the measure used, as well as the application, users, and regions. We consider some of the more severe cases of drought in the Prairies as indicated by specific water balance values.

A well-documented example of the damage from droughts is the 1999-2005 drought which is considered one of Canada’s worst natural disasters. It caused the Canadian economy to suffer a loss of $4.5 billion in 2001 to 2002 alone, with most of the damage concentrated in the Prairies and to agricultural production (Wheaton et al. 2008). More recent droughts have caused much damage in the Prairies, including the drought and heat dome of 2021, which encompassed about 99% of the agricultural prairies and resulted in considerable damage and hardship (AAFC 2022).

Pluvials, that is intense and/or extreme rainfalls, also cause damage and loss. We expand the term here to include extreme precipitation and wet spells of various sorts similar to He and Sheffield (2020). Historically, pluvials have caused less damage than droughts, likely because droughts often extend over larger areas and longer times, and therefore, affect more people, assets and places. The extensive areal coverage of droughts has been documented by Wheaton et al. (2008), for example, for Canada and even large parts of North America. Despite their lesser extent, pluvials and their associated floods still have resulted in considerable impacts, including threats to safety, and damage to infrastructure, reservoirs and agriculture. Wittrock et al. (2008) documented many costly impacts in prairie communities including flooding of homes and businesses, compromised drinking water, damaged roads and overwhelmed emergency services. Flooding hazards in the three Prairie Provinces resulted in the largest payouts from the Federal Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements during 1970 to 2014 (Halliday 2018). The estimated cost of flooding in June 2010 was over $1B. The most severely affected areas were southern Alberta and Saskatchewan where over 2,000 people were evacuated. Heavy rains also caused serious flooding in 2011 in southeastern Saskatchewan and southern Manitoba (Public Safety Canada, 2023).

Risk consists of the combination of the probability of occurrence of a hazard and the consequences of a hazard (Public Safety Canada 2012). The IPCC (2012:5) defines disaster risk as the “likelihood… of severe alterations in the normal functioning of a community or society due to hazardous physical events interacting with vulnerable social conditions leading to widespread adverse …effects…” Both the likelihood and adverse effects of droughts and pluvials are high for the Prairies, resulting in elevated levels of risk. A starting point for adaptation preparedness and vulnerability reduction is awareness and information about the changing characteristics of such climate extremes.

Research regarding the compound and complex interactions between droughts and pluvials appears as a gap in the world-wide literature (e.g., He and Sheffield 2020, Chen and Wang 2022, Chen et al. 2023). Usually, these extremes are assessed individually. The IPCC (2012) defines compound events as two or more extreme events occurring simultaneously, in close succession, or concurrently in different regions. They describe various compound events, including drought and heat, heat and precipitation extremes, drought and fire, and precipitation and wind, for example, but do not seem to consider the convergence of drought and precipitation extremes. The purpose of this paper is to address this gap by means of literature reviews and exploration of past compound droughts and pluvial events in the Prairies.

The IPCC (2021) stated that the probability of compound events has likely increased in the past due to human-induced climate change and will likely continue to increase with further global warming, and that multiple compound extremes can lead to stronger impacts than those experienced in isolation. However, a discussion of the compound occurrence of drought and heavy rains or excess moisture is missing in that source and in most other literature. An assessment of these compound events is critical as they can result in multiple stressors that quickly exceed the coping capacity of systems. Several authors stressed that the consecutive occurrence of dry and wet extremes can have larger social and environmental impacts than isolated events (e.g., He and Sheffield 2020, Wu 2022, Chen and Wang 2022, Chen et al. 2023). Rezvani et al. (2023) noted that these compound extremes may be more challenging for water managers. However, if pluvials alleviate droughts by replenishing reservoirs, wetlands, soil moisture and groundwater, the interaction can have positive impacts. Therefore, droughts and pluvials may have partial offsetting impacts depending on the amount of rainfall, event size, order, location and timing of the events. With their compound nature, however, these extremes can be a threat, impactful and even vulnerability multipliers and magnifiers.

The main research questions we address are: What literature has examined the compound characteristics of both droughts and pluvials? What are some examples of compound droughts and pluvials (CDP) in the Prairies? Our objectives are to 1) synthesize recent literature concerning the past and future possible risks of interacting droughts and pluvials, with a focus on those papers relevant to the Canadian Prairies, and 2) to provide and describe examples of Prairie CDP. We do this in two ways, one, by integrating the literature that examines droughts and pluvials separately, and two, with examples identified using the Global SPEI (Standardized Precipitation and Evapotranspiration Index) Monitor for the Prairies. The overall purpose is to improve the understanding of CDPs with special reference to the Prairies.

2. Methodology

The methods used were to 1) review the literature using synthesis and inter-comparisons, 2) use the findings from Prairie studies that consider droughts and pluvials (DP) independently and combine them to document the combined occurrence of the extremes, 3) use the Global SPEI Monitor (Beguria et al. 2023) to describe examples of compound DP in the Prairies. We focus on the 2000 to 2022 period for ease of access to data and for relevance.

These approaches also increase the understanding of the nature of hydroclimatic variability in the recent past. Pluvials are often indicators of the nature of the stages of droughts. They can determine how quickly droughts start and grow, and end, the type of persistence stages or even where they migrate. In terms of spatial patterns, pluvials may also be found adjacent to drought areas.

Relevant literature is described and findings are synthesized to assess implications for risk from CDP. Literature regarding both past conditions and future projections is considered given the expectation that they increase with continued climate change, and how adaptation for pluvials will improve adaptation to drought, such as water storage, improved infiltration, and less drainage. Perception and experience associated with these extremes play a role in adaptation and vulnerability. For example, Marchildon et al. (2016) found that wet periods tend to reduce the memory experience and awareness of drought risks exacerbating human vulnerability. This finding is yet another reason that these extremes should be considered together for reducing vulnerability.

Because of the lack of CDP literature for the Prairies, we broadened the geographic scope of the search. We emphasize literature for North America and globally, however, for relevance to the Prairie climate regions. The assessments of CDP in the Prairies are few: Szeto et al. (2011) Shabbar et al. (2011), Evans et al. (2011) and Brimelow et al. (2014). Therefore, we use a convergence of the more common separate studies on DP to explore examples of CDP in the Prairies.

Both DP extremes can be measured by various water balance indicators, such as the commonly used Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI), Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI), or the Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI). To characterize examples of the compound nature of DP events in the Prairies for selected events in 2000-2022, we use the Global SPEI Monitor (Begueria et al. 2023). The target period is September to August, the agricultural year, and the associated 12-month SPEI is the August value. A longer period has the advantage of capturing the more severe events. This approach supplements the method of the convergence of findings from separate assessments of DP. The characteristics of CDP should also be explored on a shorter time scale as use of the annual scale can smooth over shorter-term important fluctuations, especially for pluvial events. As drought and excessive moisture events are known to have decadal variations (e.g. Bonsal et al. 2004), the longer time scale patterns of CDP are also worth assessing.

A limitation of the use of the Global SPEI Monitor is that the Thornthwaite method is used to calculate the potential evapotranspiration (PET) component of the SPEI. This method has a temperature bias, and thus is considered less accurate than more complex methods, but it is often used for simplicity of calculation. Real-time data sources for more robust PET estimations are lacking and also require larger datasets. However, the Monitor has several advantages, including availability of several time scales for the SPEI, of specific grid values, for considering both wet and dry times, interactive ability, one-degree spatial resolution, time series ability, real-time, several time scales, and for access to global areas, to name a few. Therefore, this Monitor is suitable for our purposes of examining the main spatio-temporal patterns of selected CDP. In contrast, other monitors such as the North American and Canadian Drought Monitors are available only for the monthly scale and do not provide grid values, for example. Most importantly for the purposes of this paper, they do not include information for pluvials. Therefore, they are less suitable for exploring CDP characteristics.

3. Results

3.1. Literature Reviews and Synthesis

Decadal to multi-year hydro-climatic variability tends to dominate the time series of drought and excessive moisture in the Prairies (Bonsal et al. 2004, 2019). This variability occurs over a background of significant warming especially in winter and spring (Zhang et al. 2019). Bonsal et al. (2017) documented increases in inter-annual variability using the 30-year standard deviation of summer SPEI across the southern Canadian Prairies. That variability is an indicator of dry-wet switching.

Observations and simulations of the hydroclimate of the 20th and 21st centuries have a record-length limitation for capturing low-frequency variability. Proxy climate records of the past millennium, on the other hand, reveal the persistence of this scale of variability and its dominance prior to the period of greenhouse gas warming (Gurrapu et al., 2022; Sauchyn et al., 2015). For example, Kerr et al. (2022) used a network of more than 80 tree-ring chronologies to develop independent reconstructions of the warm and cold season flow of the North and South Saskatchewan Rivers since 1400. Thus, they were able to document how often drought and pluvials occur over a very large part of the prairies and conversely when excess water in one basin offsets water deficits in the other one. They found that there are more similarities between basins during wet periods than dry. This points to the patchy distribution of dry conditions and importance of local convective precipitation as a water source in dry years. Pluvials, on the other hand, generally correspond to the availability of water from large-scale mid-latitude cyclones (Basu and Sauchyn, 2022).

Although most research assesses DP events separately, Shabbar et al. (2011), Szeto et al. (2011) and Evans et al. (2011) examined some forms of CDP in the Prairies. That research was done for the Drought Research Initiative (Stewart et al. 2011) and for the 1999 to 2004 drought. These three papers appear to be the main research examining CDP in the Prairies, to the authors’ knowledge. Shabbar et al. (2011) identified extreme wet and dry seasons of the growing season (May to August) during 1950 to 2007 using the Palmer Z-Index. Their main focus was the analysis of the interrelationships among large to synoptic-scale atmospheric circulation patterns and cyclone characteristics during extreme drought and pluvial periods in the Prairies. Their Z-index time series shows considerable interannual and some multi-year variability of the time series with much wet-dry switching.

Evans et al. (2011) documented precipitation during the 1999-2004 drought at sites in Alberta and Saskatchewan. They found that precipitation events of daily accumulations of 10mm or less accounted for up to 63% of the total precipitation at these sites during that drought. They state that any understanding of drought must consider precipitation issues.

Szeto et al. (2011) characterized the catastrophic June 2002 Prairie rainstorm that occurred during the major drought of 1999 to 2004. Many locations experienced record-breaking rainfall amounts and major flooding. They showed that atmospheric conditions associated with the extreme background drought enhanced the likelihood of the co-occurrence of DP and facilitated the development of the extreme pluvial. This tremendous pluvial alleviated the drought conditions in the southern Prairies and contrasted with the still severe drought in other areas.

Brimelow et al. (2014) characterized the exceptional variability of precipitation patterns in the Canadian Prairie Provinces from 2009 to 2011. They found rapid transitions of drought to pluvial in both time and space. They show three main areas of drought and pluvial patterns in our study area during that period. Their study area extended farther north than ours, and they describe the contrast between very dry conditions in the boreal zone compared with wet conditions over far southeastern Saskatchewan and southern Manitoba.

A second type of literature of global scope demonstrates existing work on compound extremes and more specifics about the spatial and temporal patterns and methods used (

Table 1). Although the review centres on North America for relevance to the Prairies, we expanded it to include the global scale, given the scarcity of literature for our study area. The literature found for North America was for the Northern Great Plains and Midwest areas of the United States (Christian 2015; Ford et al., 2021) and for the southeastern US (Maxwell et al., 2017). Rezvani et al. (2023) assessed the Fraser, Columbia and Peace River Basins in British Columbia and a portion of northern Alberta.

Researchers have examined a range of time sequences of CDP types, from pluvial ending droughts (e.g., Christian 2015, Maxwell et al. 2017, He and Sheffield 2020) to flash droughts ending pluvials (e.g. Ford et al. 2021, Rezvani et al. 2023) (

Table 1). Several other characteristics are examined, including the number, duration and severity of these compound extremes.

The range of literature considers both past observations and reconstructions, as well as future projections. The latter tend to agree on the amplification of droughts and pluvials with drying regions having more pluvials (Martin 2018), and greater variability with shorter and more intense dry-to-wet transitions (Chen and Wang 2022). Pokharel et al. (2023) found the opposite with decreased frequency and strength of dry to wet events projected with continued warming, especially after mid-century for the Colorado River Basin. They provide ample reasons for these decreases, including the robust spring drying and shift of the North Pacific Subtropical High-pressure area. This is a reminder that different regions have different types of transitions in their climates and could likely have different climate futures.

Regarding past occurrences of CPDs, Christian (2015) found that the chance of a significant pluvial year after a significant drought year is about 25% in the Northern Great Plains of the US, adjacent to our study area. Maxwell et al. (2017) used PDSI and other methods finding that the rapid termination of drought is more common than gradual endings. He and Sheffield (2020) conclude that the transition from droughts to pluvials has increased in the past 30 years. Ford et al. (2021) found an increase in the magnitude of transition time. Rashid and Wahl (2022) determined that the number of transitions is increasing over time.

These studies used several water balance indices, such as the PDSI, SPI) and SPEI, as well as some methods developed specifically for assessments of compound extremes. These methods include the wet/dry ratio (De Luca et al. 2020) and the Event Coincidence Analysis (He and Sheffield 2021).

This selected literature review gives a range of possible methods, comparisons and findings to further explore CDP and to design work in other regions, including Canada. It indicates increasing concern and interest in CDP, but also an emphasis on global analysis and a general lack of research, especially for the regional scale.

3.2. Analysis of the Risks of Past Compound Droughts and Pluvials in the Prairies

3.2.1. Convergence of findings from research regarding Prairie droughts and pluvials

In this section, we compare and contrast the temporal and spatial characteristics of droughts and pluvials in the Prairies. First, we integrate the literature on Prairie droughts and pluvials to determine their nature as compound hazards. Then we combine the findings using the characteristics described in

Table 2 for the period 1961 to 2022. This period was selected because of the availability of documentation of major and record pluvials and droughts in the Prairies. We describe the pluvials’ characteristics, their relation to droughts and their stages, and the region(s) affected, as available. These examples were selected to demonstrate the relationships between the hydro-climatic extremes to characterize CDP.

The Prairies region is home to record intense rainfall amounts. Several of these occurred during or closely associated with drought. For example, Canada’s record intense one-hour rainfall of 250mm occurred during May 1961 at Buffalo Gap in southern Saskatchewan (Phillips 1993) (

Table 2). This was a compound extreme event because the year 1961 has been identified as the most extensive single-year Prairie drought of the twentieth century (Maybank et al. 1995). It also is the worst drought as measured by the severity and extensiveness of the August PDSI (12 month) for the 1900 to 2005 period (Bonsal et al. 2011). The May 1961 extreme rainfall occurred during the growth stage of the drought according to the stages of drought as defined by Bonsal et al. (2011, 2020) for a more precise exploration of the timing of the wet-dry connection. These stages are defined for a combination of severe drought or worse and for the percentage of grids within the agricultural region of the Canadian Prairie Provinces.

Another record rainfall was 375mm in an eight-hour storm in July 2000 in the Vanguard area of southwest Saskatchewan (Hunter et al. 2002) (

Table 2). That storm is the largest area eight-hour event recorded in the Prairies. The amount of rain exceeded the average annual precipitation total of 360mm for the area. Again, using the drought stage graphs of Bonsal et al. (2011) and SPI only, July 2000 was classified as an onset stage of the record drought of 2001 to 2002. The PDSI indicated no stage for severe drought at that time, likely because of its lag effect.

Just a few years later during that same drought of 2001 to 2002, an intense and extensive rainstorm occurred in June 2002. That deluge brought 175mm of rain to the Lethbridge area in Alberta and affected an area across the entire Prairies from western Alberta to Winnipeg, Manitoba (Szeto et al. 2011). That intense and extensive rainfall coincided with the early stage of retreat (using SPI) of the record 2001 to 2002 Prairie drought. However, using PDSI the rainfall coincided with the persistence stage of the drought, again using the stage information from Bonsal et al. (2011). The PDSI has a much greater lag effect and this would likely account for the difference in stages as the SPI would be more responsive to the pluvials.

The timing of these three examples of extreme rainstorms seems unusual as they occur during the onset, growth and persistence stages of major droughts. Many of the transitions assessed in the literature (

Table 1) examined the dry-to-wet sequence, that is, wet periods at the end or terminating the drought. Szeto et al. (2011) suggested that the extreme drought of 2002 may have enhanced the probability of the June 2002 storm they documented. We search for more examples of compound wet and dry events in the more recent period and characterize them for the Prairies in the next section.

3.2.2. Characterization of Compound Droughts and Pluvials in the Prairies using the SPEI Global Drought Monitor, 2000 to 2022

Next, we address questions about the characteristics of the CDP and selected events in the Prairies using the SPEI Global Drought Monitor, which is a suitable source for this initial exploration. These questions include the locations, intensities and spatial patterns of drought and pluvials, and indications of the strength of the gradients and the orientation of the boundary zone between wet and dry conditions (

Table 3). General locations are provided in

Table 3, but the SPEI Monitor can provide much more specific locations because of its one-degree by one-degree spatial resolution and accessible grid values.

These examples of pluvials in conjunction with droughts possibly have the more common timing occurring at the end of a drought and playing important roles in alleviating or even terminating the droughts. Unfortunately, drought stages have not been determined for these events. Wheaton et al (2013) provided an overview of the documentation of past extreme precipitation events in Saskatchewan. For the study period, they noted several examples of wet years, including 2000, 2002, 2010 to 2012. They also noted that torrential rainstorms have occurred during major droughts and that severe droughts have shifted to very wet conditions within days.

An understanding of the temporal relationships of these dry-wet and wet-dry dynamics is a scientific basis for risk assessment. Selected examples of the characteristics of the DP interactions during 2000 to 2022 are summarized in

Table 3. Dates were selected based on our knowledge of the major droughts and pluvials in the Prairies and their stages (e.g. Bonsal et al. 2020, 2011, Wheaton et al. 2013). The main areas of drought tend to be in Alberta and Saskatchewan, although the 2002, 2015 and 2021 droughts extended across the Prairies from Alberta into Manitoba. The 2021 drought is not a CDP as no pluvials existed with this SPEI value. The 2002 drought is an unusual case as the strong pluvial in the southern Prairies was associated with a northern migration of the drought area.

The locations of pluvials appear to be more variable, however, the most common pattern is associated with wetter areas in MB, and dry in the west to wetter in the east. This orientation of the dry-to-wet gradient reflects the gradients in precipitation normals. Boundaries between the drought and pluvials show variation, but these examples mostly have a north-to-south orientation. These patterns are an indication of how the CDP can change with intensities and locations, as well as the rate of change over space.

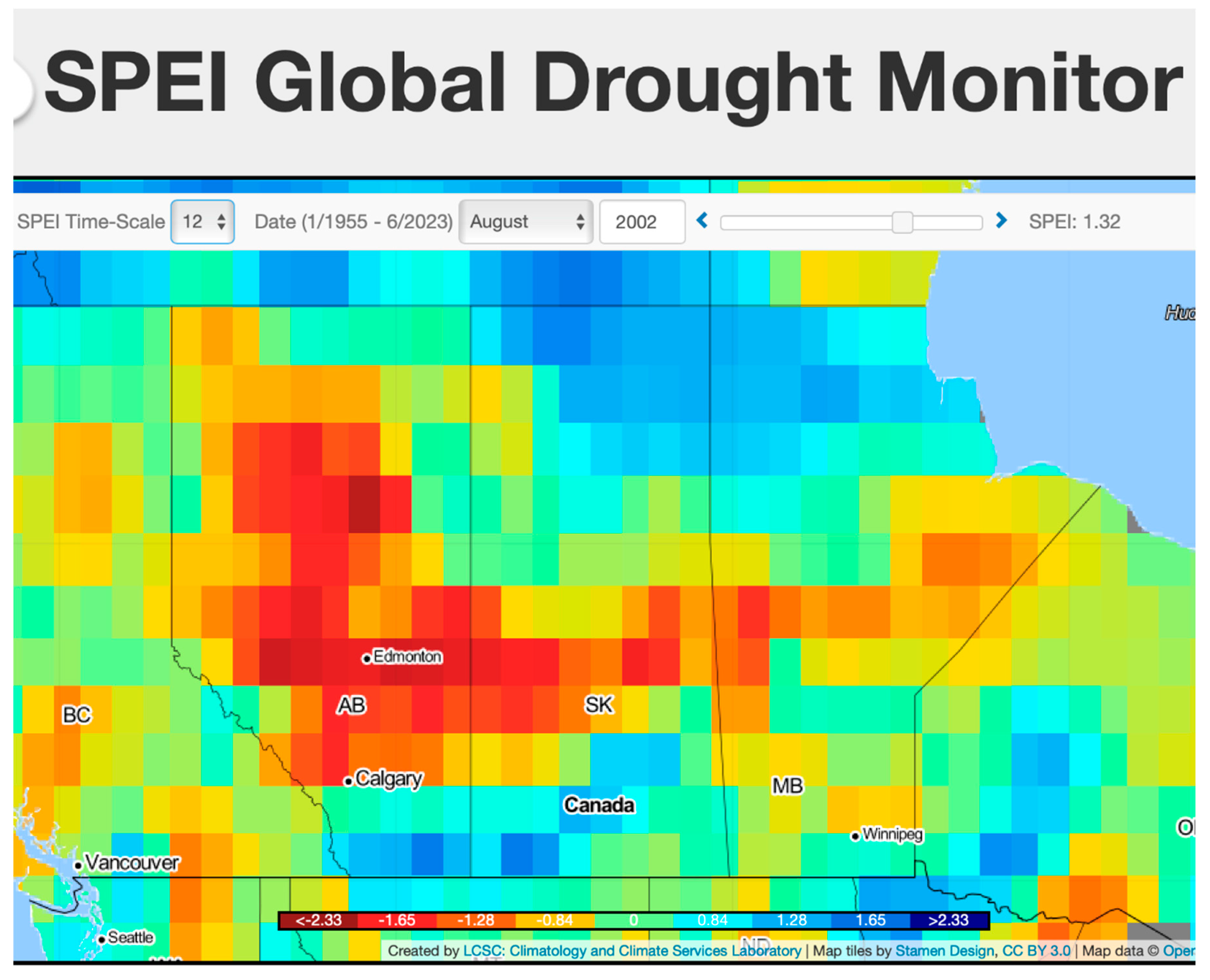

The SPEI12 month for 2002 is a case of the more unusual example of the dry to wet boundary zone that is oriented west to east (

Figure 1). It is also a good example of a strong gradient, that is rate of change, from wet in the south to dry farther north. It also shows the spatial pattern of the CDP resulting from the major rainstorm in the southern prairies in the summer of 2002 and the shifting of the drought northward. These patterns are a contrast to the more usual patterns described in

Table 2 and

Table 3.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The purposes of this paper were 1) to compare and synthesize recent literature concerning the past and future possible risks of compound droughts and pluvials with relevance to the Canadian Prairies, and 2) to explore and characterize the compound risk of drought and pluvial events in the Prairies using various data and sources. Examples are used to further advance knowledge of the risks and to enhance adaptation to these compound extremes.

Our review of the literature regarding CDP found that research that examined these extremes as separate hazards is much more advanced than studies of their joint occurrence which is quite limited. Only a few papers assessed these compound extremes on the Prairies and over a limited time period. With continued climate change, the threat of compound droughts and pluvials is an increasing concern. Many more examples of research of other types of compound extremes were found for other regions, especially drought and heat events. A few papers dealt with CDP in the United States, and more were for the global scale.

We compared and contrasted findings from integrating literature that considered Prairie drought and pluvials separately and from examining patterns of the Global SPEI Monitor to focus our analysis on the more recent past (2000 to 2022). Along with other findings, we demonstrate that variability dominates the hydroclimate of the Canadian Prairies. The variability of droughts and pluvials is likely to increase in many regions globally with climate change, according to most of the literature reviewed. Climate change is a critical driver of the changing characteristics of both drought and pluvials, therefore understanding of this effect is essential.

We demonstrate the need to more fully understand the characteristics and risks of the compound extremes of droughts and pluvials, as well as important ways to decrease vulnerability and associated damages. This paper is the first to explore the concept of and many examples of CDP for Prairies and for Canada. Although the study area is the Canadian Prairies, the work is relevant to other regions that are becoming more vulnerable to increasing risks of and vulnerabilities to such compound extremes.

Enhanced monitoring of both droughts and pluvials is critical. The Canadian and North American Drought Monitors are very useful, but should be expanded to include pluvials such that the compound nature of these extremes is better documented and understood. This need is becoming even more pronounced with continued global warming. Understanding of drought is considerably advanced by considering precipitation patterns (or lack of those) that shape the drought’s beginning, ending and other stages. The reverse holds true for wet periods as those also are shaped by interaction with dry conditions.

Gaps of knowledge abound and include the assessments of the characteristics, impacts, adaptations, and vulnerabilities associated with CDP. The recent severe and large area drought of Western North America in 2021 is a prime example. With the ending of projects such as the Drought Research Initiative (Stewart et al. 2011), new projects focused on droughts and pluvials are needed to advance understanding. Research on future characteristics of these extremes tends to emphasize the ensemble or median results. Worst-case possibilities also should be examined for appropriate risk assessment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, EW, BB, DS; Methodology: EW, BB; Data curation and analyses: EW; Writing, original draft preparation: EW; Writing-review and editing: EW, BB, DS. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Darrell Corkal for discussions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- AES Drought Study Group. 1986. An applied climatology of drought in the Canadian Prairie Provinces. Report 86-4. Canadian Climate Centre, Downsview, ON. 197 pp.

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC). 2022. Canadian Drought Monitor. Accessed 5 Dec 2022 at https://agriculture.canada.ca/atlas/maps_cartes/canadianDroughtMonitor/en/.

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC). 2023 Canadian Drought Monitor. Accessed at https://agriculture.canada.ca/atlas/maps_cartes/canadianDroughtMonitor/en/.

- Begueria, S, B. Latorre, F. Reig, S. Vicente-Serrano. 2023. SPEI Global Drought Monitor. Accessed 8 July and on at https://spei.csic.es/map/maps.html#months=1#month=4#year=2023.

- Basu, Soumik, and David J. Sauchyn. 2022. "Future Changes in the Surface Water Balance over Western Canada Using the CanESM5 (CMIP6) Ensemble for the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways 5 Scenario" Water 14, no. 5: 691. [CrossRef]

- Bonsal, B.R., G. Koshida, E.G. O'Brien, and E. Wheaton. 2004. Chapter 3. Droughts. pp. 19-25. In Threats to Water Availability in Canada, National Water Research Institute, Burlington, Ontario. NWRI Scientific Assessment Report Series No. 3 and ACSD Science Assessment Series No. 1. 128 p.

- Bonsal, B. and E. Wheaton 2005. Atmospheric Circulation Comparison between the 2001 and 2002 and the 1961 and 1988 Canadian Prairie Droughts. Atmosphere-Ocean 43(2):163-172. [CrossRef]

- Bonsal, B., Liu, Z., Wheaton, E., & Stewart, R. (2020). Historical and projected changes to the stages and other characteristics of severe Canadian Prairie droughts. Water, 12(12), 3370. [CrossRef]

- Bonsal, B.R., E.E. Wheaton, A. Meinert and E. Siemens. 2011. Characterizing the surface features of the 1999-2005 Canadian Prairie drought in relation to previous severe 20th century events. Atmosphere-Ocean, 49, 320-338. [CrossRef]

- Bonsal, B.R. and Cuell, C. (2017): Hydro-climatic variability and extremes over the Athabasca river basin: Historical trends and projected future occurrence; Canadian Water Resources Journal, v. 42, p. 315–335. [CrossRef]

- Bonsal, B.R., Peters, D.L., Seglenieks, F., Rivera, A., and Berg, A. (2019): Changes in freshwater availability across Canada; Chapter 6 in Canada’s Changing Climate Report, (ed.) E. Bush and D.S. Lemmen; Government of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, p. 261–342.

- Brimelow, J., R. Stewart, J. Hanesiak, B. Kochtubajda, K. Szeto, B. Bonsal. 2014. Characterization and assessment of the devastating natural hazards across the Canadian Prairie Provinces from 2009 to 2011. Natural Hazards. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H, S. Wang 2022. Accelerated transition between dry and wet periods in a warming climate. Geophysical Research Letters October. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H, S Wang, J Zhu, D Wang. 2023. Projected changes in the pattern of spatially compounding drought and pluvial events over Eastern China under a warming climate. Earth’s Future AGU. [CrossRef]

- Christian, J., K Christian, J. Basara, 2015. Drought and Pluvial Dipole Events within the Great Plains of the United States. J of App Met and Clim 54(9). [CrossRef]

- De Luca, P., Messori, G., Wilby, R. L., Mazzoleni, M., & Di Baldassarre, G. (2020). Concurrent wet and dry hydrological extremes at the global scale. Earth System Dynamics, 11(1), 251–266. [CrossRef]

- Evans, E., R. Stewart, W. Henson, K. Saunders. 2011. On precipitation and virga over three locations during the 1999-2004 Canadian Prairie Drought. Atmosphere-Ocean 49(4):366-379. [CrossRef]

- Ford, T. W., Chen, L., & Schoof, J. T. (2021). Variability and Transitions in Precipitation Extremes in the Midwest United States. Journal of Hydrometeorology, 22(3), 533– 545. [CrossRef]

- Gurrapu, S., Sauchyn, D. J., & Hodder, K. R. (2022). Assessment of the hydrological drought risk in Calgary, Canada using weekly river flows of the past millennium. Journal of Water and Climate Change, 13(4), 1920-1935. [CrossRef]

- Halliday, R. 2018. Flooding. Chapter 6 in Wittrock, V, R Halliday, D Corkal, M Johnston, E Wheaton, J Lettvenuk, I Stewart, B Bonsal, M Geremia. 2018 May. Saskatchewan Flood and Natural Hazard Risk Assessment. Prepared for the Saskatchewan Ministry of Government Relations. Saskatchewan Research Council, Saskatoon, SK. Revised in Dec, 2018. SRC 14113-2E18. 290p. https://publications.saskatchewan.ca/#/products/92658.

- He, X., & Sheffield, J. (2020). Lagged compound occurrence of droughts and pluvials globally over the past seven decades. Geophysical Research Letters, 47(14). [CrossRef]

- Hopkinson, R. 2010. An overview of 2010 early summer severe weather events in Saskatchewan. Custom Climate Services Inc., Regina, SK.

- Hopkinson, R. 2011. Anomalously high rainfall over southeast Saskatchewan, 2011. Custom Climate Services Inc., Regina, SK.

- IPCC, 2012: Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation. A Special Report of Working Groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Field, C.B., V. Barros, T.F. Stocker,D. Qin, D.J. Dokken, K.L. Ebi, M.D. Mastrandrea, K.J. Mach, G.-K. Plattner, S.K. Allen, M. Tignor, and P.M. Midgley (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, and New York, NY, USA, 582 pp.

- IPCC 2021 Seneviratne, S.I., X. Zhang, M. Adnan, W. Badi, C. Dereczynski, A. Di Luca, S. Ghosh, I. Iskandar, J. Kossin, S. Lewis, F. Otto, I. Pinto, M. Satoh, S.M. Vicente-Serrano, M. Wehner, and B. Zhou, 2021: Weather and Climate Extreme Events in a Changing Climate. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 1513–1766. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, F., D. Donald, B. Johnson, W. Hyde, J. Hanesiak, M. Kellerhas, R. Hopinson, B. Oegema. 2002. The Vanguard torrential storm. Canadian Water Resources Journal 27(2):213-227. [CrossRef]

- Kerr, S. A., Andreichuk, Y., & Sauchyn, D. (2022). Comparing paleo reconstructions of warm and cool season streamflow (1400–2018) for the North and South Saskatchewan River sub-basins, Western Canada. Canadian Water Resources, 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Marchildon, G, E. Wheaton, A. Fletcher, J. Vanstone. 2016. Extreme drought and excessive moisture conditions in two Canadian watersheds: comparing the perception of farmers and ranchers with the scientific record. Natural Hazards 82(1):245-266. [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, J. T., Knapp, P. A., Ortegren, J. T., Ficklin, D. L., & Soulé, P. T. (2017). Changes in the Mechanisms Causing Rapid Drought Cessation in the Southeastern United States. Geophysical Research Letters, 44(24). [CrossRef]

- Martin, E. 2018 Future projections of global pluvial and drought event characteristics. Geophysical Research Letters 45(1). [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D. 1993. The day Niagara Falls ran dry! Key Porter Books, Canadian Geographic, Toronto, ON, 226p.

- Pokharel, B., Kripa Akila Jagannathan, Shih-Yu (Simon) Wang, Andrew Jones, Paul Ulrich, Lai-Yung Ruby Leung, Matthew D. LaPlante, Smitha Buddhavarapu Krishna Borhara, James Eklund, Candice Hasenyager, Jake Serago, James R. Prairie, Laurna Kaatz, Taylor Winchell, Frank Kugel. Drought-busting ‘miracles’ in the Colorado River Basin may become less frequent and less powerful under climate warming. ESS Open Archive. April 04, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Public Safety Canada. 2012 All Hazards Risk Assessment Methodology Guidelines 2012-2-13. Public Safety Canada, Government of Canada.

- Public Safety Canada 2023. Canadian Disaster Database. Government of Canada. https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/cndn-dsstr-dtbs/index-en.aspx.

- With search results at https://cdd.publicsafety.gc.ca/rslts-eng.aspx?cultureCode=en-Ca&boundingBox=&provinces=1,12&eventTypes=%27FL%27&eventStartDate=%2720100101%27,%2720101231%27&injured=&evacuated=&totalCost=&dead=&normalizedCostYear=1&dynamic=false.

- Rashid, M. M., & Wahl, T. (2022). Hydrologic risk from consecutive dry and wet extremes at the global scale. Environmental Research Communications, 4(7), 071001. [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, R. M RahimiMovaghar, W. Na, M Reza Najafi. 2023. Accelerated lagged compound floods and droughts in Northwest North America under 1.5-4 degrees Global warming levels. J of Hyd. [CrossRef]

- Sauchyn, Dave; Jessica Vanstone, Jeannine-Marie St. Jacques, Robert Sauchyn. 2015. Dendrohydrology in Western Canada and Applications to Water Resource Management. Journal of Hydrology, 529: 548-558. [CrossRef]

- Shabbar, A., B Bonsal, K. Szeto. 2011. Atmospheric and oceanic variability associated with growing season droughts and pluvials on the Canadian Prairies. Atmosphere-Ocean:49(4):339-355. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, R., J. Pomeroy, R. Lawford. 2011. The Drought Research Initiative: A Comprehensive Examination of Drought over the Canadian Prairies. Atmosphere-Ocean 49:297-302. [CrossRef]

- Szeto K, Henson W, Stewart R, Gascon G. 2011. The catastrophic June 2002 prairie rainstorm. Atmosphere-Ocean 49: 380–395. [CrossRef]

- Tam, B.Y.; Szeto, K.; Bonsal, B.; Flato, G.; Cannon, A.J.; Rong, R. CMIP5 drought projections in Canada based on the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index. Can. Water Resour. J. 2019, 44, 90–107. [CrossRef]

- Wheaton, E., S. Kulshreshtha, V. Wittrock, G. Koshida. 2008 Summer. Dry Times: Lessons from the Canadian Drought of 2001 and 2002. The Canadian Geographer 52(2):241-262. Saskatchewan Research Council (SRC) Publication No. 11927-6A06. [CrossRef]

- Wheaton, E, B. Bonsal, V. Wittrock. 2013 November. Future Possible Dry and Wet Extremes in Saskatchewan, Canada. Prepared for the Water Security Agency of Saskatchewan. Saskatchewan Research Council, Saskatoon, SK. SRC #13462-1E13 35 p.

- Wittrock, V., S. Kulshreshtha, L. Magzul, E. Wheaton. 2008. Adapting to Impacts of Climatic Extremes: Case Stud of the Kainai Blood Indian Reserve, Alberta. Prepared for the Institutional Adaptation to Climate Change Project. Saskatchewan Research Council, Saskatoon, SK. Publication No. 11899-6E08. 94+ pp.

- Wittrock, V., E. Wheaton, and E. Siemens. 2010 March. More than a Close Call: A Preliminary Assessment of the Characteristics, Impacts of and Adaptations to the Drought of 2009-10 in the Canadian Prairies. Prepared for Environment Canada Adaptation and Impacts Research Division (AIRD), Saskatchewan Research Council. SRC Publication No. 12803-1E10. 124pp.

- Wittrock, V, R Halliday, D Corkal, M Johnston, E Wheaton, J Lettvenuk, I Stewart, B Bonsal, M Geremia. 2018 May. Saskatchewan Flood and Natural Hazard Risk Assessment. Prepared for the Saskatchewan Ministry of Government Relations. Saskatchewan Research Council, Saskatoon, SK. Revised in Dec, 2018. SRC 14113-2E18. 290p. https://publications.saskatchewan.ca/#/products/92658.

- Zhang, X., Flato, G., Kirchmeier-Young, M., Vincent, L., Wan, H., Wang, X., Rong, R., Fyfe, J., Li, G., Kharin, V.V. (2019): Changes in Temperature and Precipitation Across Canada; Chapter 4 in Bush, E. and Lemmen, D.S. (Eds.) Canada’s Changing Climate Report. Government of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, pp 112-193.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).