Introduction

Dementia is the seventh highest cause of death and one of the primary causes of disability and dependency among the world’s elderly, with over 55 million cases reported globally and 10 million new cases documented annually (WHO, 2023). This high universal prevalence is only set to increase (Davis et al., 2021). As of September 2022, 451,992 people in the United Kingdom had a diagnosis of dementia (NHS Digital, 2022). However, given the low percentages of persons receiving a formal diagnosis, determining the total number of people with dementia is difficult (Mitchell et al., 2013).

Dementia is not a specific condition, but rather a broad term that describes a person's cognitive capacity diminishing beyond what is expected with natural ageing effects, interfering with normal responsibilities, and typically being chronic and progressive in nature (CDC, 2019; WHO, 2023). Symptoms of dementia can include disruption to an individual's attention (Hamdy et al., 2017), memory, thinking, orientation, comprehension, arithmetic, learning capacity, language, and judgement, which are frequently accompanied by changes in mood, emotional control, behaviour, or motivation (WHO, 2023). However, in most cases, memory impairments are prevalent, with episodic memory losses to be the first manifestation of most forms of dementia (Dröes et al., 2011; Kalenzaga et al., 2013). Therefore, this study aimed to investigate whether the way individuals with the disease encode information can improve their memory in order to minimise the impact of the impairments on their daily life.

Memory performance is one of the most complex and multifaceted aspects of cognition (Harvey, 2019), wherein several processes are involved such as the Self-Reference Effect (SRE). This is the tendency for information encoded with reference to self to be better recalled than information encoded about other individuals (He et al., 2021). The work on SRE gained attention after the seminal work of Rogers et al (1977). They conducted two experiments to explore how the self affects the handling of personal information, examining four forms of encoding: structural, phonemic, semantic, and self-reference. It was observed that recall of words was best under the self-reference task. This could be because attending to self-relevant information is said to require fewer attentional resources, whereas rejecting self-relevant information involves more (Bargh, 1982). Furthermore, the SRE has been verified by a meta-analysis that compared semantic, other-referential and self-referent encoding finding that the latter improved memory (Symons & Johnson, 1997).

Works on SRE have shown self-concept to be significant in the processing, interpretation, and remembering of personal information (Rogers et al., 1977). Self-concept is considered to encompass the whole individual, including all features, attributes, mentality, and consciousness. However, the notion of self is obscure (Millet, 2011) and vague (Burns & Dobson, 1984). Various approaches to studying self and identity in dementia have been used (Caddell & Clare, 2010) which has resulted in some research showing that the self remains intact within dementia (Fazio & Mitchell, 2009), while others argue that it degenerates until nothing one is left (Davis, 2004). For example, Fazio and Mitchell, (2009) examined the preservation of self in people with suspected Alzheimer’s disease (AD) using linguistic and visual self-recognition tasks and found that people with dementia retain their sense of self. In contrast, studies that investigated the relationship between memory and self, has found that those living with dementia have a decreased sense of self (Addis & Tippett, 2004). This could be explained by an impaired self-awareness in the form of anosognosia which is present in around 25-75 % of AD patients (Antoine et al., 2004). The problem associated with self-image in patients with dementia may arise due to the failure in updating their episodic knowledge about themselves (Ruby et al., 2009).

Systems of the self and memory has been believed to be interlinked (Strikwerda-Brown et al., 2019) thus the sense of self an individual with dementia has is an area frequently investigated. It is often stated that the collection of memories from significant personal experiences naturally gives rise to a "sense of self", or the sensation that we exist as a unique and distinctive individual (Prebble et al., 2013). Views such as this have frequently led to the notion that there can be no self without memory (Strikwerda-Brown et al., 2019). In the similar vein, with memory impairments prevalent in dementia, it is believed that individuals living with the disease gradually lose their sense of self (Downs et al., 2014). For example, in a study Addis and Tippett (2004) found that individuals with AD had significant impairments on the memory tests, along with changes in the strength and quality of their identity. Diminished sense of self in dementia could, therefore, pose a challenge when exploring the impact of the SRE in individuals with dementia. However, a more recent study questions this concept of loss of self that despite substantial episodic memory impairments and overall cognitive decline, the self remains essentially intact (Rathbone et al., 2019). They used “ I am” tasks such as ‘I am a Father’ to explore the self in dementia and found that the self remains intact which is supported by general perseveration of semantic memories in AD. Therefore, it is important to ensure semantic memories are not disregarded when pursuing research in areas such as the SRE.

Previously, research on the self has been hindered due to differing views on whether episodic or semantic memories are more significant in maintaining identity (Rathbone et al., 2019). This has led to the belief that the different forms of memory are autonomous, uniform, and unchanging (Prebble et al., 2013). Humans are naturally motivated to see their sense of self as consistent across time (Locke, 1690; cited in Strikwerda-Brown et al., 2019). Sustaining this is usually described in the context of episodic memory (Strikwerda-Brown et al., 2019). A distinguishing feature of this type of memory is autonoetic consciousness, which is based on the concept of 'mental time travel' and hence is the recall of personal memories from prior events in which one was present (Gardiner, 2001). Therefore, it is the ability to identify time in terms of everything that has happened to the self (Shayna Rosenbaum et al., 2017) giving a sense of subjective self-continuity (Strikwerda-Brown et al., 2019). However, it is also necessary to acknowledge the role of semantic memory in sustaining self-continuity over time as this is considered to offer a narrative continuity of the self (Strikwerda-Brown et al., 2019). This is especially important for those who live with dementia as they have been found to have an impaired autonoetic consciousness (Kalenzaga et al., 2013), and thus could explain loss of sense of self in dementai. A narrative continuity of self allows individuals to build an objective self-schema, for instance being a mother or a doctor, in order to unite past, present and future selves (Strikwerda-Brown et al., 2019). The Life Story Model (McAdams, 2001) supports this idea, stating that individuals in modern societies provide unity and meaning to their life by developing internalised and growing narratives of the self. It is illustrated by an individual's noetic consciousness which has been shown to be preserved in those with dementia (Kalenzaga et al., 2013). While not expressed with any form of self-recollection, noetic consciousness does convey the awareness of familiarity (Gardiner, 2001). The two forms of consciousness is useful in providing understanding of the notion of self.

The Remember/Know Paradigm (Tulving, 1985) provides the ability to distinguish between the two forms of consciousness linked to episodic and semantic memory. This requires participants to remember a list of words, which are subsequently re-presented in a random order for a recognition test, along with some additional distractor words. For each test word, participants have to first indicate whether it was on the study list by replying with 'Yes’ or ‘No'. If they respond with ‘Yes’ then they are asked to state what this decision was based on, answering with either ‘Remember’ or ‘Know’. A 'Remember' response indicates that they can consciously recall an experience they had at the time the word was to be remembered, exhibiting autonoetic consciousness. A 'Know' response, on the other hand, expresses noetic consciousness, implying that subjects recognise the word on some other basis. Previous research has found that AD patients produce considerably fewer 'Remember' responses for correctly recognised items than controls (Barba, 1997). Additionally, they produce the same amount (Barba, 1997) or more 'Know' responses compared to controls (Rauchs et al., 2007), demonstrating the involvement of noetic consciousness.

Previous research on the SRE in dementia have focused the states of consciousness linked with memory recall rather than the effect in general. However, research in this area is still limited (Carson et al., 2018). Lalanne et al. (2013) reported that prior to their work, the SRE on long-term episodic memory and autonoetic consciousness was primarily studied in young individuals, rarely in older adults, and never in AD patients. They found that self-referential encoding significantly enhanced performance during the two recall tasks for both the young and older adults but not for those diagnosed with AD. This is supported by neuroimaging research which found self-referential encoding did not ameliorate the significant source of memory deficits in AD and Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) (Wong et al., 2017). Individuals with dementia may experience a loss of subjective continuity of self, leading to an outdated sense of self and diminished autonoetic consciousness which can reduce SRE (Kalenzaga et al., 2013). However, other studies have shown that memory of those living with AD can benefit from self-referential encoding to a certain degree (Kalenzaga et al., 2013) and may have a reduced SRE.

The SRE is frequently explored utilising a Trait Evaluation Paradigm. For this, individuals must determine whether a set of traits are true of themselves or a well-known other-referent, if they fit a semantic category, or if they meet a superficial processing criterion. For instance ‘To what extent does this adjective describe Jacques Chirac?”, “To what extent does this adjective describe you?” , “Is ‘calm’ a positive word?” or “Is ‘calm’ written in upper or lower case?” (Cunningham & Turk, 2017; Kalenzaga & Clarys, 2013). However, the Trait Evaluation Paradigm may produce misleading results and not show effects of self-referential encoding on memory as individuals living with dementia may have an outdated image of oneself.

Recently researchers have employed a more naturalistic approach to assessing the SRE (Cunningham & Turk, 2017). The “Ownership Procedure” utilises the idea of associating the self with external stimuli to demonstrate self-referential encoding. This idea is supported by the Self-Memory System (SMS; Conway & Pleydell-Pearce, 2000) which is frequently used as a theoretical explanation for the SRE. The SMS combines an autobiographical knowledge underpinning with the working self (Conway, 2005; Conway & Pleydell-Pearce, 2000) meaning memories are typically maintained in accordance with the working self's current aims (Koppel & Berntsen, 2015). Therefore, it illustrates that the SRE should be found not only when information is framed by autobiographical knowledge, such as that obtained in the Trait Evaluation Paradigm, but instead in any information encoded in connection with the self, extending to everyday interactions between the self and external inputs (Cunningham & Turk, 2017). Van den Bos et al. (2010) utilised the Ownership Procedure, asking participants to place objects in baskets that belonged to either themselves or a fictitious person. They found that objects encoded in the context of self-ownership were more consistently recognised than items encoded in the context of other-ownership. This demonstrates that constructing a self-referential encoding context leads to extensive and comprehensive representations in episodic memory (van den Bos et al., 2010). Therefore, the SRE is suggested to include the extended self' (Belk, 1988) where our possessions are a key contribution to and expression of our identities. Memory enhancement through ownership is not only limited to healthy individuals but found to produce significant memory enhancement in dementia patients (Blessing et al., 2019).

The present study aimed to investigate the SRE in dementia patients using the more naturalistic approach of the ownership procedure, alongside the Remember/Know Paradigm. This combination of approaches is a novel method which has not been used in the earlier studies. Furthermore, the study aimed to examine if the SRE effect is based on autonoetic remember memory process or noetic know memory process.

Method

Participants

Twenty people were recruited through opportunistic sampling by approaching people who attend community-run dementia groups, their carers, and age matched individuals from community. The sample was divided into two groups: one served as a control group, and the other consisted of dementia patients. All dementia patients had a prior diagnosis of either Vascular dementia (VaD), AD or FTD. However, one participant withdrew, and another participant was removed as they were unable to recognise any item presented during the recognition phase. Three control participants had below the cut-off score of 26 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA; Nasreddine et al., 2005), indicating a probable mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and thus their data was withdrawn. The data was analysed with the remaining 15 participants.

The age of the two group participants did not differ considerably, with dementia patients, controls, ranging from 93-65 and 87-59 respectively. According to the MoCA, two of the dementia patients were mildly impaired, four were moderately impaired and one was severely impaired. The control group scored 26 or above on the MoCA, indicating that they have no cognitive impairments. The whole sample had a White Caucasian background with 12 or more years of education and English was their first language.

Table 1 displays further demographic characteristics.

Materials and Procedure

Research ethics approval was given by the Psychology Research Ethics Committee at Oxford Brookes University (Approval number: 6012/054/22). Participants were assessed individually and provided informed consent before beginning the process. For the participants with dementia, informed consent was gained from those legally responsible for the individuals' care, such as family members or carers, who were present during the testing, with assent provided by the participants. All subjects underwent the MoCA to assess their cognitive ability before undertaking an encoding task using the Ownership Procedure. A five-minute break was then provided before a recall task using the Remember/Know Paradigm.

MoCA

The MoCA was developed to address the challenges around the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein et al., 1975) in detecting early dementia (Nasreddine et al., 2005). It takes around 10 minutes to administer and assesses short-term memory, visuospatial ability, numerous elements of executive functions, attention, concentration, working memory, language and orientation (Nasreddine et al., 2005). Individuals are graded out of 30, with a cut-off score of 26 (Nasreddine et al., 2005). MoCA has proven to be reliable - with a cronbach alpha of 0.83 - valid - with it highly correlating with the MMSE (r= 0.87) (Nasreddine et al., 2005) - and moderately sensitive (Costa et al., 2013), after an extra score was given to those who received less than 12 years of education (Nasreddine et al., 2005). It has also been shown to be an accurate screening instrument for those with dementia in general (Davis et al., 2021) but also specifically for AD (Nasreddine et al., 2005; Pinto et al., 2018), VaD (Freitas et al., 2012) and FTD (Freitas et al., 2012).

Encoding Task

The Ownership Procedure, like that used in the studies conducted by van den Bos et al. (2010) and Blessing et al. (2019) was used for the participants to encode information. However, unlike previous research, this study used physical objects. The participants were instructed to imagine themselves shopping at a supermarket. The participants were provided a basket and another basket was kept by the researcher. The participant was then asked to select 15 things from a bag loaded with familiar grocery items to place in their basket. They then had to choose 15 items for the researcher's basket. To ensure no harm came to the subjects, children's shopping toys were utilised. Subsequently, the baskets were hidden under a blanket while the subjects took a five-minute break before the recall task was performed.

Recall Task

The Remember/Know Paradigm (Tulving, 1985) was used to assess recognition memory. Participants were shown objects from their basket, the researcher's basket, and 15 previously unseen objects randomly. For each object they were asked to state whether they recognise choosing the objects to put in either of the baskets. If they responded an item to be old, the participant had to say whether their decision was based on what they remembered or if they felt the object was familiar. Therefore, a 'Remember' response was given, if the participant recalled the object from the previous activity; conversely, a 'Know' response was provided, if the participant only had a small recollection of the object. A “no” response was also recorded if they reported not placing the object in either of the baskets. False positives were also recorded where participants responded that an object was old for objects that were not previously presented.

Data Analysis

The data was analysed using a repeated-measures ANOVA with the 2 subject groups (Dementia and Control) as the between subjects factor and the 2 memory scores (Remember and Know) and 2 referential encoding (Self and Other) as within subject factors. Significant interaction effects were analysed using Tukey post hoc test. Additionally, another repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted as exploratory analysis with the participant groups as between subject factors and number of False Positives as a within subject factor. Furthermore, an exploratory correlational analysis was also conducted investigating the relationships between the separate aspects of cognitive functioning examined in the MoCA and the participants’ memory scores.

Results

Table 2 displays the descriptive characteristics of memory and MoCA scores. whilst

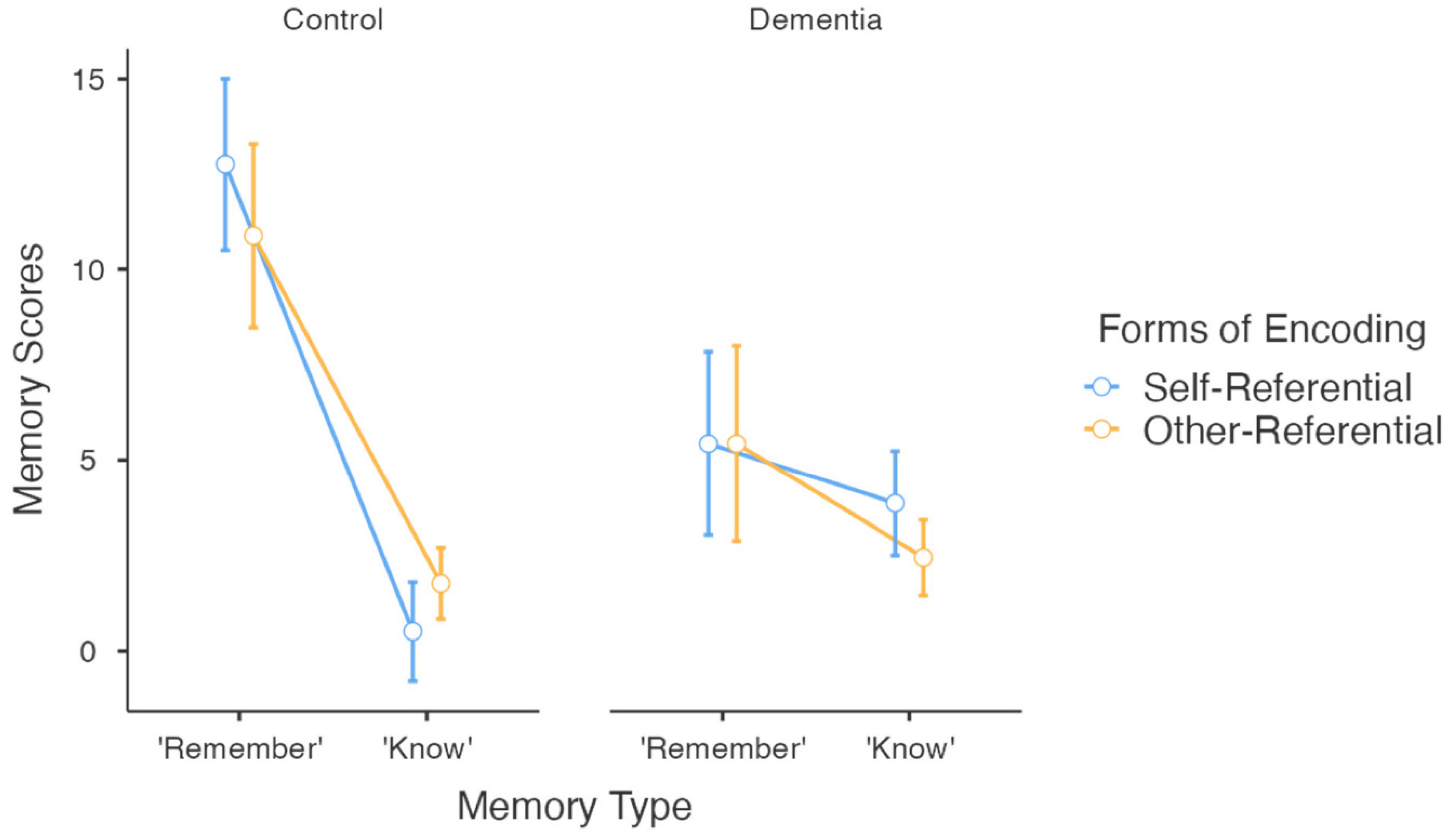

Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the data.

The repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a statistically significant 3 way interaction in the number of items recalled and the type of memory responses provided between those living with dementia and controls, F(1, 13) = 5.07, p = .042, η²p = .28. Tukey post hoc analyses showed that the control group slightly benefited from self-referential encoding and had a higher (non-significant; p=.374) remember score on the self condition than the other condition. However, the dementia group did not show any difference between the self and other perspective on remember score (p=1.00). The differences on know responses for the control and dementia group were not significant (p=.712 and p=.647) between self and other conditions.

The two way interaction between the groups and memory type was also significant (F(1, 13) = 26.48, p < .001, η²p = .671) where the dementia group did not have a significantly different remember and know score ( p=.268) and the control group had a significantly higher remember score than know score ( p<.001). An overall significant effect of memory type showed higher score for remember responses than know responses (F(1, 13) = 61.13, p < .001, η²p = .829). The analysis also showed a significant main effect for group where the control group had significantly higher overall memory scores than the dementia group (F(1, 13) = 8.94, p < .01, η²p = .41). No other main effects or interaction were significant ( all ps>.05).

False Positive Responses

The repeated-measures ANOVA detected a statistically significant difference in the number of false positive responses provided between the groups,

F(1, 13) = 11.04,

p = .006,

η²p = .46 where the dementia participants had significantly more false positive responses compared to the control group (see

Table 2).

Discussion

Memory performance is one of the most complicated and broad aspects of cognition (Harvey, 2019) that can be influenced by several factors including the SRE (Rogers et al., 1977). The SRE theory highlights the importance of the perception of oneself in the processing, understanding, and recollection of personal information (Rogers et al., 1977). The memory impairments are hallmark features of dementia. Nevertheless, memory and self have long been believed to be intricately linked (Locke, 1690; cited in Strikwerda-Brown et al., 2019) often leading to the conclusion that individuals with dementia progressively lose their sense of identity until there is barely anyone left (Downs et al., 2014), bringing into question their ability to self-encode. However, recent research has demonstrated the role semantic memory could play in an individual’s self-concept, opening up the possibility of aiding memory in those with dementia through self-referential encoding; albeit a reduced effect compared to controls.

This study did not show SRE in dementia patients since there were no significant differences in the number of items they recalled that were self-referentially encoded versus those that were other-referentially encoded. This finding is supported by pervious work which has shown that self-referential encoding failed to improve memory performance (Lalanne et al., 2013). Previous neuroimaging research also did not find significant influence of self-referential encoding on memory problems in patients with AD and FTD (Wong et al., 2017). However, these findings are in contrast to the findings of Kalenzaga et al. (2013) who had shown self-referential encoding in individual who lives with dementia. SRE is a robut effect observed in several research on healthy control participants (Lalanne et al., 2013; Rogers et al., 1977; Symons & Johnson 1997). We used a more naturalistic methodology of the Ownership Procedure. Prior work has shown that items fictitiously owned by dementia patients improve their memory substantially (Blessing et al., 2019). However, the lack of SRE in memory for the individuals with dementia in our study may suggest that dementia sufferers may not view material belongings as a significant part of their identity, thus may lack a sense of an 'Extended Self’ (Belk, 1988). It is also possible that the shopping task they were asked to do may not capture their working self aims as suggested by the SMS (Conway & Pleydell-Pearce, 2000). Individuals with dementia are likely to have an impaired subjective sense of self-continuity (Strikwerda-Brown et al., 2019), and only having a sense of their premorbid personality (Klein et al., 2003). Therefore, the sense of self of these individuals is likely to be impaired and that weakens the contribution the self makes to the memory system (Addis & Tippett, 2004). However, some research report the self stays largely intact in persons with AD (Rathbone et al.,2019) maintained by semantic memory system (Strikwerda-Brown et al., 2019). As our research investigated SRE on episodic memory, no effect of SRE on memory may also indicate non-reliance of the task on semantic memory system that supports continuity of the self in individuals with dementia. Whereas, healthy individuals have a self system that supports their memory and we also observed that the control group in our study showed some effect of SRE on the remember responses (although not significant).

The lack of SRE effects on memory in dementia can still provide a unique usnderstanding of the disease. Such an effect could be the result of an impaired autonoetic consciousness of those with dementia (Barba, 1997; Kalenzaga et al., 2013). This notion is supported by the findings from our study that those in the control gave significantly more ‘Remember’ responses than ‘Know’ responses. However, individuals with dementia had similar number of responses for “Remember” and “Know” condition.

The lack of self-related contribution to the memory in dementia is also supported by increased false positive memory responses in dementia. In our study, compared to the control group, those with dementia gave significantly more false positive responses. The increased false positive responses could be associated with anosognosia (Antoine et al., 2004), which is a common problem in dementia. Problems in self-awareness is manifested in ability to recognise or appraise the degree of perceptual, emotional, motor, sensory, or cognitive functioning deficits. Therefore, the false positive responses may have been due to a lack of self awareness in memory monitoring.

In summary, our research points that memory facilitation by SRE typically observed in healthy individuals may not benefit individuals with dementia. Several memory strategies are used to support individuals with dementia as studies have shown that increasing the usage of memory strategies result in a decrease in reported everyday memory issues (McKean & Hunter, 2017). Our study suggests that memory strategies that focus on knowing, familiarity and narrative self-continuity could aid the memory impairments of the individuals living with dementia. However, our findings should be treated with caution as we had a small sample size.

Author Contributions

FB and SK conceptualised the study, FB collected the data, FB and SK analysed the data, FB and SK drafted the manuscript, SK provided the overall supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was available for this research.

Data Availability:

The anonymous data can be made available to any researcher upon their.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Addis, D., & Tippett, L. (2004). Memory of myself: Autobiographical memory and identity in alzheimer's disease. Memory, 12(1), 56–74. [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. (2023). Apa Dictionary of Psychology. American Psychological Association. Retrieved March 27, 2023, from https://dictionary.apa.org/abstraction.

- Antoine, C., Antoine, P., Guermonprez, P., & Frigard, B. (2004). Conscience des déficits et anosognosie dans la maladie d’alzheimer. L'Encéphale, 30(6), 570–577. [CrossRef]

- Barba, G. D. (1997). Recognition memory and recollective experience in alzheimer's disease. Memory, 5(6), 657–672. [CrossRef]

- Bargh, J. A. (1982). Attention and automaticity in the processing of self-relevant information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43(3), 425–436. [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. W. (1988). Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(2), 139–168. [CrossRef]

- Blessing, A., Fritsche, S., Hess, C., & Dammann, G. (2019). The ownership effect in dementia patients. GeroPsych, 32(4), 181–185. [CrossRef]

- Burns, R. B., & Dobson, C. B. (1984). The self-concept. Introductory Psychology, 473–505. [CrossRef]

- Caddell, L. S., & Clare, L. (2010). The impact of dementia on self and identity: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(1), 113–126. [CrossRef]

- Carson, N., Rosenbaum, R. S., Moscovitch, M., & Murphy, K. J. (2018). Self-reference effect and self-reference recollection effect for trait adjectives in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 24(8), 821–832. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, April 5). About Dementia. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved January 23, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/aging/dementia/index.html.

- Conway, M. A. (2005). Memory and the self. Journal of Memory and Language, 53(4), 594–628. [CrossRef]

- Conway, M. A., & Pleydell-Pearce, C. W. (2000). The construction of autobiographical memories in the self-memory system. Psychological Review, 107(2), 261–288. [CrossRef]

- Costa, A. S., Reich, A., Fimm, B., Ketteler, S. T., Schulz, J. B., & Reetz, K. (2013). Evidence of the sensitivity of the MOCA alternate forms in monitoring cognitive change in early alzheimer's disease. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 37(1-2), 95–103. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, S. J., & Turk, D. J. (2017). Editorial: A review of self-processing biases in cognition. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 70(6), 987–995. [CrossRef]

- Davis, D. H. J. (2004). Dementia: Sociological and philosophical constructions. Social Science & Medicine, 58(2), 369–378. [CrossRef]

- Davis, D. H. J., Creavin, S. T., Yip, J. L. Y., Noel-Storr, A. H., Brayne, C., & Cullum, S. (2021). Montreal cognitive assessment for the detection of dementia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2021(7). [CrossRef]

- Downs, M., Bowers, B. J., & Kontos, P. C. (2014). Selfhood and the Body in Dementia Care. In Excellence in dementia care: Research into practice (pp. 122–131). essay, McGraw Hill Education/Open University Press.

- Dröes, R.-M., van der Roest, H. G., van Mierlo, L., & Meiland, F. J. M. (2011). Memory problems in dementia: Adaptation and coping strategies and psychosocial treatments. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 11(12), 1769–1782. [CrossRef]

- Fazio, S., & Mitchell, D. B. (2009). Persistence of self in individuals with alzheimer's disease. Dementia, 8(1), 39–59. [CrossRef]

- Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E., & McHugh, P. R. (1975). Mini-mental State Examination. PsycTESTS Dataset. [CrossRef]

- Freitas, S., Simões, M. R., Alves, L., Duro, D., & Santana, I. (2012). Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA): Validation study for frontotemporal dementia. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 25(3), 146–154. [CrossRef]

- Freitas, S., Simões, M. R., Alves, L., Vicente, M., & Santana, I. (2012). Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA): Validation study for vascular dementia. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 18(6), 1031–1040. [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, J. M. (2001). Episodic memory and autonoetic consciousness: A first–person approach. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 356(1413), 1351–1361. [CrossRef]

- Hamdy, R. C., Lewis, J. V., Kinser, A., Depelteau, A., Copeland, R., Kendall-Wilson, T., & Whalen, K. (2017). Too many choices confuse patients with dementia. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine, 3, 233372141772058. [CrossRef]

- Harvey, P. D. (2019). Domains of cognition and their assessment. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 21(3), 227–237. [CrossRef]

- He, L., Han, W., & Shi, Z. (2021). Self-reference effect induced by self-cues presented during retrieval. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. [CrossRef]

- Kalenzaga, S., Bugaïska, A., & Clarys, D. (2013). Self-reference effect and autonoetic consciousness in alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders, 27(2), 116–122. [CrossRef]

- Kalenzaga, S., & Clarys, D. (2013). Self-referential processing in alzheimer's disease: Two different ways of processing self-knowledge? Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 35(5), 455–471. [CrossRef]

- Klein, S. B., Cosmides, L., & Costabile, K. A. (2003). Preserved knowledge of self in a case of alzheimer's dementia. Social Cognition, 21(2), 157–165. [CrossRef]

- Koppel, J., & Berntsen, D. (2015). The peaks of life: The Differential Temporal locations of the reminiscence bump across disparate cueing methods. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 4(1), 66–80. [CrossRef]

- Lalanne, J., Rozenberg, J., Grolleau, P., & Piolino, P. (2013). The self-reference effect on episodic memory recollection in young and older adults and alzheimer’s disease. Current Alzheimer Research, 10(10), 1107–1117. [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D. P. (2001). The Psychology of Life Stories. Review of General Psychology, 5(2), 100–122. [CrossRef]

- McKean, A., & Hunter, E. (2017). The Home Based Memory Rehabilitation Programme in dementia – an update on the Occupational Therapy improvement journey in Scotland. Retrieved July 27, 2022, from http://www.knowledge.scot.nhs.uk/media/CLT/ResourceUploads/4095501/49b47a55-37e9-459a-9dec-d84f7739bf45.pdf.

- Millett, S. (2011). Self and embodiment: A bio-phenomenological approach to dementia. Dementia, 10(4), 509–522. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, G., McCollum, P., & Monaghan, C. (2013). Disclosing a diagnosis of dementia: A background to the phenomenon. Nursing Older People, 25(10), 16–21. [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, Z. S., Phillips, N. A., Bédirian, V. Ã., Charbonneau, S., Whitehead, V., Collin, I., Cummings, J. L., & Chertkow, H. (2005). The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MOCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 53(4), 695–699. [CrossRef]

- NHS. (2022, October 20). Recorded Dementia Diagnoses, September 2022. NHS Digital. Retrieved December 16, 2022, from https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/recorded-dementia-diagnoses/september-2022.

- Pinto, T. C., Machado, L., Bulgacov, T. M., Rodrigues-Júnior, A. L., Costa, M. L., Ximenes, R. C., & Sougey, E. B. (2018). Is the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA) screening superior to the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) in the detection of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and alzheimer’s disease (AD) in the elderly? International Psychogeriatrics, 31(04), 491–504. [CrossRef]

- Prebble, S. C., Addis, D. R., & Tippett, L. J. (2013). Autobiographical memory and sense of self. Psychological Bulletin, 139(4), 815–840. [CrossRef]

- Rathbone, C. J., Ellis, J. A., Ahmed, S., Moulin, C. J. A., Ernst, A., & Butler, C. R. (2019). Using memories to support the self in alzheimer's disease. Cortex, 121, 332–346. [CrossRef]

- Rauchs, G., Piolino, P., Mézenge, F., Landeau, B., Lalevée, C., Pélerin, A., Viader, F., de la Sayette, V., Eustache, F., & Desgranges, B. (2007). Autonoetic consciousness in alzheimer's disease: Neuropsychological and pet findings using an episodic learning and recognition task. Neurobiology of Aging, 28(9), 1410–1420. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, T. B., Kuiper, N. A., & Kirker, W. S. (1977). Self-reference and the encoding of personal information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35(9), 677–688. [CrossRef]

- Ruby P, Collette F, D'Argembeau A, Péters F, Degueldre C, Balteau E, Luxen A, Maquet P, Salmon E. Perspective taking to assess self-personality: what's modified in Alzheimer's disease? Neurobiol Aging. 2009 Oct;30(10):1637-51. [CrossRef]

- Shayna Rosenbaum, R., Kim, A. S. N., & Baker, S. (2017). Episodic and semantic memory. Learning and Memory: A Comprehensive Reference, 87–118. [CrossRef]

- Strikwerda-Brown, C., Grilli, M. D., Andrews-Hanna, J., & Irish, M. (2019). “all is not lost”—rethinking the nature of memory and the self in dementia. Ageing Research Reviews, 54, 100932. [CrossRef]

- Symons, C. S., & Johnson, B. T. (1997). The self-reference effect in memory: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 121(3), 371–394. [CrossRef]

- Tulving, E. (1985). Memory and consciousness. Canadian Psychology / Psychologie Canadienne, 26(1), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- van den Bos, M., Cunningham, S. J., Conway, M. A., & Turk, D. J. (2010). Mine to remember: The impact of ownership on recollective experience. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 63(6), 1065–1071. [CrossRef]

- Wong, S., Irish, M., Leshikar, E. D., Duarte, A., Bertoux, M., Savage, G., Hodges, J. R., Piguet, O., & Hornberger, M. (2017). The self-reference effect in dementia: Differential involvement of cortical midline structures in alzheimer's disease and behavioural-variant frontotemporal dementia. Cortex, 91, 169–185. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2023, March 15). Dementia. World Health Organization. Retrieved March 28, 2023, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).