2. Operationalization of the University Business Collaboration in curriculum design, development and delivery

The Think4Jobs project was rooted in the creation of a partnership between HEI and LM organisations to create real-case situations/problems to be used in the blended curricula to trigger the students CT (skills and dispositions) and the solution of specific, real-life problems in each profession. In the next section we will analyse and critically discuss the design, development, and delivery of Critical Thinking Blended Apprenticeships Curricula. To achieve the aim of the project for the design, development, and delivery of CT blended apprenticeships curricula, the Think4Jobs consortium followed a Participatory Co-Design approach [

7] to blend CT within the core-content of Courses in five programmes or disciplines: Teacher Education (Greece), Veterinary Medicine (Portugal), Business and Economics (Romania), Foreign Language Teaching (Lithuania), and Business Informatics (Germany). According to Simonsen and Robertson [

7], participatory design is a methodology that emphasises stakeholders’ active involvement in the design of products, services, learning environments or interventions. It also ensures that all needs, requirements or perspectives of stakeholders or end-users are considered during the design process. Still, we refer to co-design as perceived by Sanders and Stappers [

23], namely “

the creativity of designers and people not trained in design working together in the design development process” (p. 6). In the context of UBC, the key stakeholders involved in the Participatory Co-Design (PC-D) may include Higher Education Teachers, Students, Labor Market Tutors), Employees, and Researchers.

Considering the specific objectives that the final product should meet, in our case the CT blended apprenticeships curricula, at each phase of the PC-D methodology various research designs and data collection approaches were exploited. PC-D often involves multiple iterations, where stakeholders are involved in continuous reflection and adaptation of ideas. However, the key steps of the PC-D methodology are needs analysis and requirements gathering, design and development, implementation, and evaluation [

24].

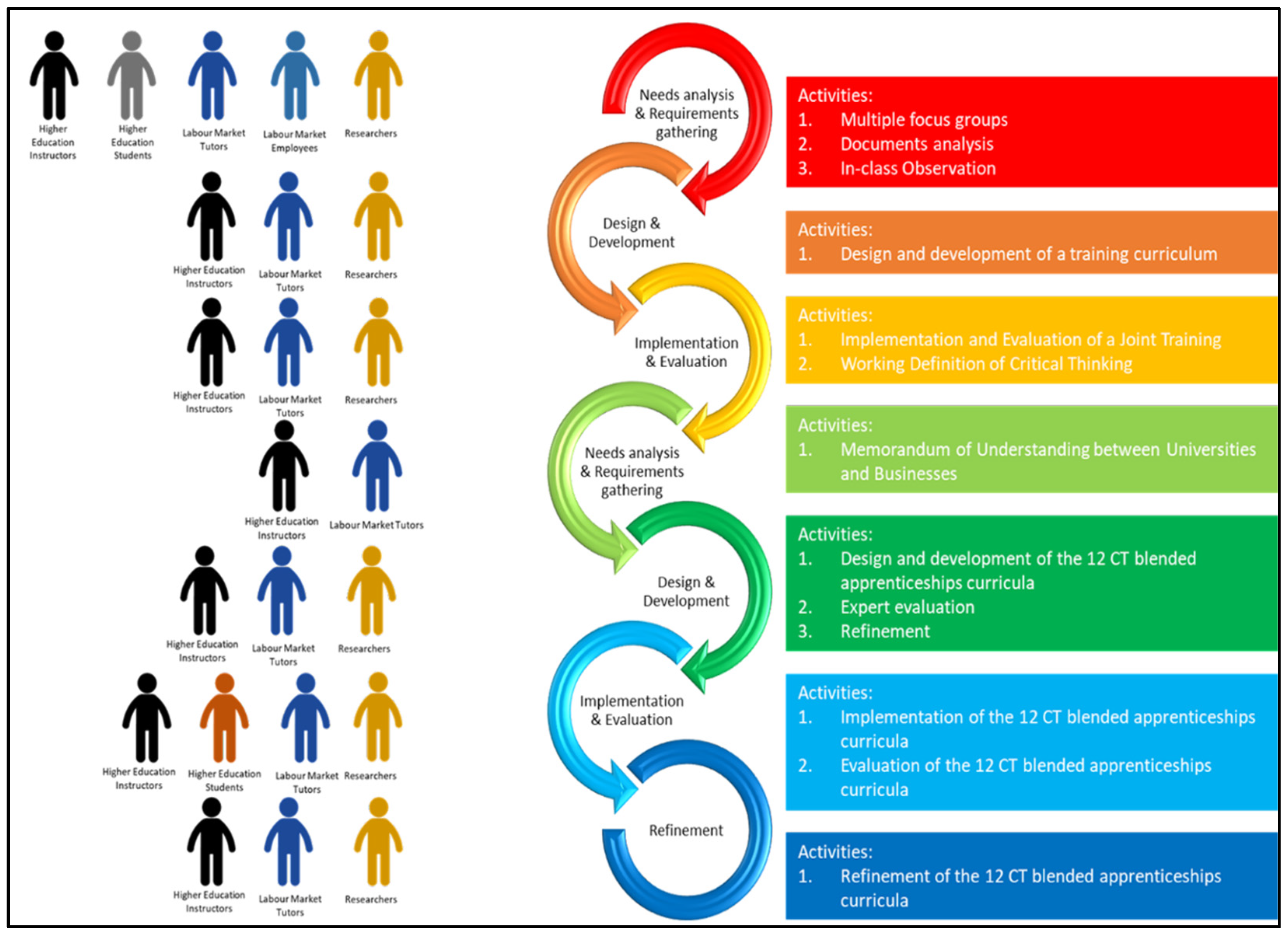

Figure 1 is a visual representation of the iterative steps of the PC-D leading to the preparation of the CT blended apprenticeships curricula. In addition,

Figure 1 shows the main activities implemented at each step, as well as the key-stakeholders involved in each step of the methodology.

Step 1 - Needs analysis and requirement gathering

The first step was a needs analysis and requirements gathering aimed at identifying how CT is promoted in learning and instruction both in HEI and the LM. Particularly, multiple focus groups engaging Higher Education Instructors and Students, Labour Market Tutors, and Employees as well as Researchers were implemented in this step. In addition, various documents employed in HEI and LM, such as handbooks and training materials, were analysed. Moreover, HE Instructors and LM tutors were observed during instruction. One of the main findings underlined that HEI and LM are in parallel regarding their understanding and implementation of CT [

25]. Therefore, the needs analysis is deemed essential for designing and developing a training curriculum that would facilitate HE Instructors and LM Tutors to develop a shared understanding of CT.

Therefore, a training curriculum was developed to create a common understanding between the HEI and LM organisations engaged in the project [

26]. For the design process of the training curriculum, 41 HE Instructors and LM Tutors from all countries were involved in a focus group discussion that identified their learning needs and essential topics to be addressed during the training. The training was implemented and evaluated engaging 35 HE Instructors and LM Tutors from all countries as participants of an intensive experiential, learner-centred, online training with a duration of five days. The intensive course addressed various topics, such as the conceptualization of CT, how CT can be promoted through instruction, and how CT can be assessed. The evaluation of the training was assessed through a quasi-experimental design with a questionnaire administered prior to and after the training [

26]. To foster the development of a common ground between HE Instructors and LM Tutors during the intensive training, two invaluable collaborative activities were applied, engaging the university and business partners, namely, a working definition of CT and five Memoranda of Understanding. The co-design of the definition of Critical Thinking allowed the HE Instructors and LM Tutors to decide on the theoretical frameworks that would support the design of the CT blended apprenticeship curricula considering the specificities of each discipline. The working definition resulted from a workshop that deconstructed and reconstructed participants’ knowledge of conceptual, procedural and assessment aspects of CT following a conceptual change approach [

27].

The working definition of CT co-designed by HE Instructors and LM Tutors integrated aspects from several CT theoretical frameworks [

15,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Following, we present the working definition of CT agreed and employed throughout the design and development of the CT blended apprenticeship curricula:

Critical Thinking is a purposeful mental process driven by conscious, dynamic, self-directed, self-monitored, self-corrective thinking, which is sustained by disciplinary and procedural knowledge as well as metacognition (metacognitive, meta-strategic, epistemological). CT can be trained as well as developed through competence building and is scaffolded by attitudes (e.g., systematicity, open-mindedness, empathy, flexibility, cognitive maturity), and intellectual skills (e.g., reflection, self-regulation, analysis, inference, explanation, synthesis, systematicness). It triggers problem-solving abilities, enables effective communication, promotes independent, holistic thinking, and supports decision-making and participative citizenship.

At the end of the training course, five MoU were prepared as a joint effort among HE Instructors and LM Tutors who participated in the training. One MoU was prepared per discipline, considering the specific learning needs identified in the first step namely needs analysis and requirements gathering. MoU were considered as guiding documents, capturing the shared vision, learning objectives, and desired outcomes of the CT blended apprenticeships curricula. They provided a framework for collaboration, ensuring that the curricula addressed the specific disciplinary knowledge, skills, and competencies required by the labour market. The HE Instructors brought their expertise in curriculum development, pedagogical approaches, and disciplinary knowledge, and partners contributed with their real-world insights and practical experiences. Still, the most significant aspect of the MoU was the definition and agreement among parties on the role and responsibilities of HE Instructors and LM Tutors during the CT blended apprenticeships curricula [

26]. Throughout this collaborative activity, challenges and successes were encountered. One notable challenge was achieving effective communication between the university and business partners, given the different organizational cultures and perspectives. However, through open dialogue, active listening, and mutual respect, this challenge was overcome, leading to a more harmonious collaboration. One of the major successes of the collaborative process was the finalization of the co-design of the MoU, which provided a framework for collaboration, ensuring that the curricula addressed CT, as well as the specific disciplinary knowledge, skills, and competencies required by the labour market.

The PC-D approach allowed project partners to engage twice in a needs analysis and requirements gathering and to carefully tailor the designed CT blended apprenticeships curricula to the needs of students and employers.

Step 2 - Design and Development of blended curricula

Following the previous step, Universities and Businesses collaborated on the design and development of the CT blended apprenticeships curricula [

32]. The collaboration involved joint planning and decision-making to integrate theoretical knowledge with real-life problems into the curricula. Among others, the collaboration aimed to align the pedagogical approaches, learning outcomes, and assessment methods of the CT Blended Apprenticeships Curricula. Existing curricula were refined to incorporate direct and indirect instruction of CT, problem-solving, blended learning approaches, combining online and face-to-face instruction, practical experiences, and work-integrated learning opportunities, in a process safeguarded by the signed MoU. The majority of the curricula claimed to address the CT skills and dispositions as defined by Facione [

28]. However, additional skills or dispositions from other CT related frameworks [

15,

29,

30,

33,] were also integrated into the curricula but varied according to the specificities of the five disciplines addressed in the project.

Apart from the common aspects concerning CT, the curricula analysed in this study revolved around fostering active learning through constructivist teaching approaches and instructional methods. Students were presented with subject-specific problems or tasks issued from the labour market realities, requiring independent and collaborative problem-solving within high cognitive levels of Bloom's taxonomy. Instructors played a supportive role, providing the necessary theoretical content, facilitating discussions, and offering continuous feedback. The culmination of students' work was often presented at the end of the curriculum or activity, which was assessed alongside disciplinary skills. Overall, the curricula aimed to cultivate CT by integrating it seamlessly into the learning process. Later, we attempt to describe how the curricula were further tailored to meet the needs of both students and employers, as well as describe in detail the curricula developed and the UBC per country. The curriculum design will be detailed later when describing the implementation of the pilot curricula.

After a preliminary design proposal, researchers evaluated the curricula along with invited experts from each discipline. After this evaluation HE Instructors and LM Tutors refined their proposal and finalised their development using MOODLE, a free and open-source learning management system [

34]. A milestone was reached with the finalisation of the development of the CT blended apprenticeship curricula. The whole process that resulted in the development of the CT blended apprenticeship curricula lasted one year and yielded 13 curricula [

32]. Table 1 presents the curricula developed per discipline and country.

Table 2.

The CT blended apprenticeships curricula per discipline and country.

Table 2.

The CT blended apprenticeships curricula per discipline and country.

| Country |

Discipline |

Curricula |

| Germany |

Business

Informatics |

Design Patterns

Economic Aspects of Industrial Digitalization |

| Greece |

Teacher

Education |

Teaching of Biological Concepts |

| Teaching of Science Education |

| Teaching of the Study of the Environment |

| Lithuania |

Foreign Language

Teaching |

Childhood Pedagogy |

| English language for International Relations and Political Science |

| Portugal |

Veterinary

Medicine |

Imaging |

| Deontology |

| Gynaecology, Andrology and Obstetrics |

| Romania |

Business

and Economics |

Business Communication |

| Pedagogy and Didactics of Financial Accounting |

| Virtual Learning Environments in Economics |

Step 3 - Delivery of the pilot blendedapprenticeship curricula

In the delivery of the pilot CT Blended Apprenticeship Curricula, HE Instructors and LM Tutors were in close collaboration. A total of 609 HE students enrolled in the pilot Courses. Students involved in the implementation of the curricula differ from those engaged in the needs analysis. Researchers asked in advance students’ written consent for participation in the study. Below we present a brief description of the activities implemented in each country and the articulation between the HE instructors and LM partners' roles in the CT blended apprenticeship curricula implemented.

Germany

In the development of the curricula, the following aspects were addressed: (1) requirements and expectations of the German university and LM partners regarding CT, (2) specific characteristics of the subject Business Informatics, and (3) the developmental level of the students (Bachelor/Master). Identified needs included a focus not only on teaching factual knowledge at HE but also on explicitly promoting CT through the practical application of this knowledge to subject-specific scenarios and use cases. CT skills and dispositions based on Facione’s framework [

28] were included in the intended learning outcomes of the curricula. Current research on pedagogical approaches that support active learning, and the promotion of CT was consulted. During the implementation of the curriculum, an atmosphere of acceptance and tolerance was developed to encourage students to actively engage in learning activities and conversations without fear of failure, both at HE and in the context of LM.

In Germany, the two courses “Design Patterns” and “Economic Aspects of Industrial Digitalization”, have been redesigned to align teaching and learning on both the delivery of subject-specific content and the promotion of CT skills and dispositions. The infusion approach was used to promote CT, integrating CT teaching into subject-specific instruction, and making the general principles of CT explicit to students [

35]. General aspects of CT [

28] were presented to the students. The first course was offered by the LM partner as part of its own apprenticeship educational program, while the second course was offered by the academic partner in the context of a HE programme. In the first course, students learned how to use software design patterns to overcome typical software development challenges. The students learned to analyse software requirements to be developed, and based on this analysis, to select a design pattern that is best suited to meet these requirements. They also analysed and evaluated the consequences of selecting a design pattern where several other alternatives could have been chosen. The second course dealt with the interrelationships and interdependencies between digital technology and organisational digitalisation. Students learned to understand, describe, analyse, and evaluate the impact of digital technology on the economy, society, organisations, and individuals from different perspectives and at multiple levels.

The UBC in Business Informatics was comprehensive. A frequent information exchange took place especially during curriculum design and development. University teachers assisted LM instructors in designing and developing courses and individual learning activities to promote and to assess CT while LM instructors contributed current issues and use cases from LM to design CT learning scenarios.

Greece

In the Teacher Education discipline, the LM representatives identified needs encompassing five crucial aspects. Firstly, teachers are expected to develop CT skills to handle critical incidents during instruction (e.g., problematic student behaviour or conflicts). In particular, student-teachers excel in designing lesson plans and choosing the appropriate teaching strategies but struggle adapting to unexpected in-class situations. Secondly, they lack self-confidence in their role as teachers, which in return affects their decision-making. Moreover, understanding the complexity of teachers’ roles is another issue identified, and exposure to ill-structured problems and case studies could help tackle it. Further, LM representatives considered that exercising student-teachers on parental communication is essential. Finally, students-teachers should be familiarised with administrative routines and collegial collaboration. Although all needs were considered imperative, some of them, such as familiarisation with parental communication, collegial collaboration and school administration could not be addressed as the disciplinary aims and objectives of the curricula engaged in the study deviate significantly as they focus on content-specific instruction and not general pedagogical knowledge. Still, to address the rest of the identified needs, critical incidents as well as instructional approaches like problem-based learning and case-based learning, were incorporated in the curricula.

As far as the CT-specific needs are concerned, the LM Tutors engaged in the preparation of the MoU suggested that flexibility and reflection are two essential dispositions and skills that future teachers should depict in practice. Therefore, apart from the framework of Facione [

28], these two additional skills were addressed.

Two of the three CT blended apprenticeship curricula in Teacher Training had a similar structure: “Teaching of Science Education” and “Teaching of the Study of the Environment”. The students designed lesson plans for practical applications, accompanied by reflection sessions at the university. In the curriculum “Teaching of Biological Concepts”, theoretical classes preceded the students' lesson plan design, with feedback provided in university classes. All curricula promoted CT with the infusion approach [

35], where subject-matter instruction was combined with explicit instruction of CT. Moreover, critical incidents, problem-based learning, and case studies were further exploited to train student-teachers CT skills and dispositions. The curriculum “Teaching of the Study of the Environment” included additional case studies related to the design of lesson plans for further training on CT. Reflection of student-teachers' lesson plans varied among the curricula. The curriculum “Teaching of Science Education” offered student-teachers highly guided and structured reflections, in contrast to the other two curricula.

The UBC in the discipline of Teacher Education was consolidated on the role of the LM tutors as mentors of the student-teachers during the implementation of the curricula. The LM tutors who acted as mentors brought their experience in learning and instruction. In addition, the mentors acted as facilitators, who guided and provided their expertise to student-teachers not only on the design of the lesson plans but also on their implementation. Moreover, their familiarisation with CT facilitated explicit support to students, while solving cases and problems requiring CT skills and dispositions. Still, some differences were spotted among the three curricula and the role of the mentors, namely the LM Tutors. At the curriculum “Teaching of Science Education”, the mentors provided via MOODLE feedback to student-teachers in some problem-solving activities. Further, they provided feedback to the student-teachers twice, namely after having designed and implemented their lesson plans. Moreover, in the curriculum “Teaching of the Study of the Environment”, mentors evaluated the answers student-teachers provided to the case-studies that the HE Instructor assigned the student-teachers. Finally, in the curriculum of “Teaching of Biological Concepts”, mentors only provided feedback to the student-teachers after having designed and presented their lesson plans.

Lithuania

The initial focus group interviews carried out in the discipline of Foreign Language Teaching highlighted the need to provide a less constricted learning paradigm, less focused on forms, rules, and rigid frameworks. It was decided that more stress should be placed on the content and ideas necessary for the everyday use of language. In today's life, students should be critical and consider the political and historical background of the region or the people they interact with. Besides media and information literacy competencies, CT skills involve autonomy, argumentation skills, creativity, and communication. There is a conscious effort to stimulate and develop those competencies and skills in class.

For the project, two CT-blended curricula were designed. The first one was used in the study programme of Childhood Pedagogy. It was carried out, but not successfully evaluated. In this course, students prepared projects describing how a particular topic could be instructed to pupils. They presented those projects to the HE Instructor and the LM Tutor, subsequently receiving feedback. Since the evaluations were deemed invalid, the results were not considered, and they were not included into the overall analysis of the results.

The second blended curriculum was a mandatory first year “English language course for International Relations and Political Science”. The activities were designed according to the conceptualization of the learner as a social agent. Language activities were performed in a particular social context and real-life, according to the action-oriented approach to foreign language teaching and learning described by Piccardo and North [

36] and included in the updated version of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment [

37]. In collaboration with the LM partners, different scenarios replicating authentic cases were designed, in which the students were asked to play a specific role (political advisers, political analysts, childhood education teacher, among others). Within the context of the cases, students were asked to analyse the situation, and propose a suitable solution based on core knowledge, and, finally, make recommendations. They were also requested to propose a project or a conference presentation on a given topic (to familiarize themselves with the requirements of academic writing), to be presented and discussed in class.

Other activities designed to foster CT skill in this subject were parliamentary-style debates, writing an academic essay, writing a research proposal, and describing a case study on one of the topics related to political science and international relations. Students were expected to resort to critical analysis and compare the research findings from the scientific sources and triangulate them with the social, political, or economic contexts to provide relevant examples, decide on solutions, and identify implications.

Portugal

In the Veterinary Medicine field, the identified needs related to informed decision-making, whether in the clinical or non-clinical practice, for which students must critically assess a poor or ill-defined problem, distinguish between confounding factors, propose a solution, anticipate any disruptive outcome, while being able to interact and communicate with multiple persons requesting different language levels. Trainers refer to students as shy persons, insecure and with low autonomy even when executing routine technical procedures, mainly when unsupervised. The activities were designed considering three curricula of the Veterinary Medicine Master. Two redesigned curricula were “Imaging” (5

th semester), a pre-clinical subject - and “Gynaecology, Andrology and Obstetrics” (7

th semester), a clinical course. In the latter, some steps designed to structure the communication with clients were also introduced in the activities. Together with the LM partner, it was decided to focus the activities to be developed in the blended curricula on developing clinical reasoning using a sort of “

how do doctors think” - deconstructing the clinical reasoning into multiple interwoven small steps starting with the initial evaluation of a clinical case, aiming at deciding on the most adequate solution for the proposed problem [

20]. The reasoning was scaffolded by a set of questions that would provide some guidance across the students' tasks. Another curriculum was designed and implemented “

Deontology” where the focus of the designed activities was the analysis of a dilemmatic situation, the identification of a possible approach to establish legislative recommendations and the presentation and discussion of the solutions proposed before an audience.

For each activity proposed, representatives of the LM partners identified a set of CT skills and dispositions to be triggered within each course, and the pedagogical approach selected by the teachers of the courses according to its potential usefulness in the medical area. In general, the designed activities were intermingled with the core content of the curricula; their location across the semester varied with the Course. It was dispersed along the semester, in three specific moments, for the courses “Gynaecology, Andrology and Obstetrics”, and “Deontology”, while for “Imaging” the activities located in the last third of the semester.

The UBC was operationalised as follows. In the pre-clinical and clinical subjects, two practitioners of the Atlantic Veterinary Hospital (HVA) selected the case vignettes from their clinical records and retrieved all the clinical notes and the results from the complementary exams to construct the case. This collaboration was critical, because it allowed us to bring situations occurring in real life into the classes. These colleagues also revised and proposed some changes in the rationale behind the questioning that scaffolded the activities and, in the case of the “Gynaecology, Andrology and Obstetrics” course, detailed the different levels of clinical reasoning to solve each situation. Similar situations were replicated with students from the HVA tutored under the course “curricular traineeship”. For the “Deontology” course, another colleague from HVA, who is also a Board representative of the Order of Veterinary Surgeons, helped to identify critical public concerns in the profession with a dilemmatic configuration.

In all the courses, each activity was followed by the production of a document that would be evaluated. More than responding to the questions, students were asked to detail and critically analyse the reasoning that led them to the proposed solution. The documents produced were evaluated under two dimensions: a/ the factual and conceptual course-related knowledge; and b/ the quality of the reasoning process and the ability to evidence the procedural and metacognitive dimensions of knowledge. At the end of the activities, after assessing those documents, feedback was provided to students. Albeit the partners involved in the activities design, they were not directly involved in the students’ assessment, except for students in the curricular traineeship course.

Romania

As far as the Romanian needs are concerned in the discipline of Business and Economics, it was apparent that the LM Tutors highlighted the need to change the instructional approaches employed by the Instructors at the University. This change aimed to establish a more dynamic environment centred on the students as central actors in settings promoting learning through experience and the development of competencies for easy integration into the labour market. They pinpoint the need to develop the student’s self-confidence in reasoning and communication, which requires an atmosphere of acceptance and tolerance. They also mentioned the need to develop students’ ability to ask questions and to analyse the opinions and assumptions of others logically. In addition, it was highlighted that a more experiential approach to learning should be employed during learning and instruction. In that way, students would delve into understanding and constructing knowledge through their own real-life experiences.

The Romanian partners developed three courses: “Virtual Learning Environments in Economics”, “Business Communication” and “Didactics and Pedagogy of Financial Accounting”. All three courses aimed to develop CT skills and dispositions through an inquiry-based, constructivist teaching approach. Each module involved specific learning tasks and assessment activities. The “Virtual Learning Environments in Economics” course aimed to develop a virtual learning environment using the Google Sites solution for a subject chosen by the student. The “Business Communication” course involved analysing several case studies. The “Didactics and Pedagogy of Financial Accounting” course put the students in a position to discover the methods, didactic approach, materials, and tools used by the trainer, as well as to design three learning scenarios for concrete lessons and textbook assessment.

From the needs analysis, we found that a bottom-up approach to teaching was preferred by the students, starting from their experience, and gradually connecting concepts and moving to the theoretical part of the lesson. LM was more inclined to base their teaching on such a strategy, and half of the lessons were held by the LM trainer alone or by the LM trainer and HE teacher together. In these respective sessions we used learning by discovery, problem-based and project-based learning, case-studies or role-plays for skills development, and metacognitive strategies to promote awareness, open-mindedness, and intellectual humility.

Together with the LM partners, case studies, trigger situations (like a set of images) and other learning scenarios were used so the students had to analyse specific situations, following the LM partners’ most used framework [

38]. Each group of students was given a case study (work daily situation, a set of images or a problem), write questions, describe concepts, make judgements, and discuss their ideas or decisions. After a time to reflect on and debate the topic presented, a decision or a solution should be presented considering new contexts that may arise, identification of motivations, concrete client need, and experimentation. The LM partner participated in some sessions with a presentation of a training section they usually have during in-service training, with students in trainee roles, to provide insights in different approaches available for the design of activities or to approach communication issues.

The UBC was extensive, and all the classes were co-designed to ensure a common vision of CT development. The total curriculum time was divided into two halves, one half for the LM and the other half for the university teacher. Even though the trainer was the main teacher, the university teacher was always present in the class. Due to time limitations, the LM trainers were not present in the university teacher's classes. The classes were intertwined, meaning that the LM trainers and university teachers had activities when the respective theme was coming into the schedule. LM teaching activities were mainly practical, with many everyday examples from working in a bank or as a trainer in a bank. Students were asked to perform specific tasks and think as if they were employees. Decision-making involved all the CT skills mentioned in the previous sections. The educational activities carried out by the university teachers used top-down approaches. Concept-driven and concept-making tasks were used to bring the scattered experiences accumulated with the LM trainer into the current theoretical frameworks.

Step 4: Evaluation of the curricula regarding CT skills and dispositions

Researchers were engaged in the process of evaluation of students’ CT; in particular, they determined the data collection process, and identified the data collection tools and data analyses [

43]. The consortium proposed to assess the effects of the implemented interventions on the CT skills and dispositions using a pre- and post-test questionnaire that joined in one single form a scale addressing CT skills [the short-form of the Critical Thinking Self-Assessment Scale (SF-CTSAS), with 60 items] and dispositions [Student-Educator Negotiated Critical Thinking Dispositions Scale (SENCTDS), with 21 items]. In a preliminary moment both the scales were validated in a population of 531 university students originated from the five countries and proven to be suitable for our objectives (Cronbach’s 𝛼=.969 for SF-CTSAS and Cronbach’s 𝛼=.842 for SENCTDS) [

43]. The questionnaire was shared with the students enrolled in the courses piloting the CT blended apprenticeships curricula using Google Forms. Of the 609 students enrolled in the courses (44 from Germany, 156 from Greece, 61 from Lithuania, 205 from Portugal, and 143 from Romania), only 286 students (85.4%) completed the pre-test and post-test form (22 from Germany, 103 from Greece, 20 from Lithuania, 100 from Portugal, and 81 from Romania). The respondents unevenly represented the consortium, the three most represented countries being Greece, Portugal, and Romania. Also, it is important to note that each country represents a different discipline, thus, country comparisons might also represent differences among the main disciplines (ranging from Education in Greece and Lithuania, to Business in Romania, Engineering in Germany and Veterinary Medicine in Portugal). Besides the questionnaire, additional summative assessment measures were applied in relation to each curriculum, such as rubrics, essays, or students’ narratives.

Overall comparison of pre-test and post-test responses evidenced a gain in CT skills across the participants (p≤ .0001) for the integrated skills score (gain=5.85 units), as well as in all the skills subdimensions analysed (Interpretation, Evaluation, Analysis, Inference, Explanation and Self-regulation). The gains were more pronounced in the skills of explanation (gain=1.42 units), analysis (gain=1.12 units) and interpretation (gain=1.42 units). A minor gain was observed in Self-Regulation (gain= .61 units); however, the initial score in this sub-dimension was rather high (mean in 8.57 in 12), which could make larger increments difficult. Comparing the most represented countries among the respondents (Greece, Portugal and Romania), the changes in the overall CT skills score were higher for the Portuguese students (7.14 units), compared with the Greek (6.13 units) and Romanian´s (3.43 units) (p=.038).

Regarding CT dispositions, the changes across the consortium were less perceptible. The average gain recorded in the dispositions’ integrated score was equal to .18 and failed to reach statistical significance (p=.394). Significant positive changes were only recorded in the disposition of Organization (gain=.18; p=.011) while a negative effect was recorded for open-mindedness (gain=-.20; p=.009). Considering the latter dimension, the scores for this dimension were relatively high at the pre-test moment (average scores ranging from 5.06 in Greek students to 5.91 in Portuguese students), which makes it difficult to get significant changes. Still, when comparing the most represented countries among the respondents (Greece, Portugal and Romania), the changes in the overall CT dispositions score were higher for the Portuguese students (.92 units) compared with the Greek (-.30 units) and Romanian´s (-.25 units) (p=.042).

The different impact of the interventions on the CT skills and dispositions observed in this study may result from the fact that changing attitudes in a short length period (like an academic semester) is harder than changing procedures (way of thinking), as the former will require an intrinsic willingness and effort to engage with, while the later represent procedural behaviour triggered by training. An unexpected finding meriting further consideration was the decrease in the score of the open-mindedness disposition after the implementation of the curricula. A possible explanation for this result is that the curricula indirectly fostered students' intellectual humility [

29], a disposition that is interwoven with open-mindedness and for some scholars is perceived as a second-order open-mindedness [

50]. On the one hand, open-mindedness is the willingness to consider new ideas, perspectives and evidence avoiding any personal biases as well as it refers to the reception of challenging opinions. On the other hand, intellectual humility is the recognition of one’s knowledge and the acceptance that one's beliefs or understanding may be fallible or incomplete [

29]. Previous empirical studies have identified a positive relationship between open-mindedness and intellectual humility [

40,

41]. We can argue that at the pre-measurement students enrolled in the curricula perceived scoring higher on open-mindedness, but after explicit instruction on CT they became aware of their cognitive limitations. Thus, the original high score in open-mindedness decreased in the post-measurement. Future evaluation of the CT blended apprenticeships curricula could devote greater attention to the relationship between open-mindedness and intellectual humility measuring the latter explicitly.

Step 5: Refinement of the curricula

Finally, after having evaluated the impact of the curricula on students' CT [

39], researchers suggested improvements to the curricula, which HE Instructors and LM Tutors integrated into their designs, refining in that way the developed curricula. The refined curricula are in the process of being implemented and re-evaluated.

3. Project Best Practices

So far, we tried to present the UBC for the design, development, and implementation of the CT blended apprenticeship curricula across the three-year life cycle of the Think4Jobs project. The experience gained allowed the consortium to glean some insights regarding the key success factors, namely the most effective approaches, methods, and strategies that facilitated us to meet the objectives of the project. Below we present a list of the best practices that contributed to the Project’s success.

Best Practice 1: Definition of a common conceptualization for Critical Thinking

Ennis [

36] highlighted an essential aspect when implementing CT across the curriculum to have a “meaning for CT”. This also proved to be efficient for the current project. After mapping how CT was carried out in the contexts of University and Business, the formulation of a working definition of CT was considered imperative to achieve a starting point for the shared understanding between Universities and Businesses. Although one can identify some variations in the CT skills and dispositions defined among the disciplines, the core conceptualization of CT was reciprocal and fundamental for the identification of needs and the modifications of curricula. A lack of agreement in the definition of CT could compromise the UBC’s effectiveness in identifying and reducing existing gaps or mismatches between academia and the LM.

Best Practice 2: Employment of a participatory approach

The methodological approach employed in the project, namely participatory co-design, allowed for another key-success factor to emerge. Participatory approaches are valuable as they ensure the active engagement and participation of key stakeholders in the design process. In our case, key stakeholders, such as LM Employers and Employees, Higher Education Instructors and Students, were engaged in the design process of the curricula. Their input was essential and allowed us to identify teaching approaches that would meet the demands of the business sector. Therefore, the approach employed allowed us to better align the curricula to the stakeholders’ needs. Moreover, the alignment of the curricula to the stakeholders’ needs fostered the development of a more effective and impactful learning environment for students CT, as revealed by our results. Other similar initiatives regarding the design of Engineering or Accounting curricula, have highlighted the importance of a cooperative model between university and business rendering the approach as sufficient for “bridging the gap” between the labour market needs and knowledge provided by higher education programs [

42,

43,

44,

45].

Best Practice 3: Common Training

Rooted in best practices 1 and 2, the common training of university and business partners in the current project fostered the development of a shared understanding and a common language among the involved parties. This understanding, in return, facilitated smoother interactions and a more coherent approach to curriculum design and implementation and may have led to the use of common strategies to nurture CT by either the LM or HE. In addition, the common training promoted a sense of partnership, ownership, and cooperation as the two entities addressed problem-solving in a joint and supportive way, which contributed to a positive and productive working relationship.

Best Practice 4: Clear Objectives, Explicit Roles and Responsibilities

The development of the MoU between University and Business partners proved essential, as it allowed them to align their vision and objectives for the collaboration. Eventually, this practice led to the design of curricula tailored to meet the LM’s needs. Moreover, it allowed the establishment of well-defined and mutually agreed-upon objectives for the curriculum design and the collaboration, per se. In that way, it ensured that the HEI and LM had a common perspective of the expected outcomes. Beyond the clear objectives, explicitly identifying the roles and responsibilities of the university and LM parties ensured that the entities were aware of their specific contributions and obligations. This fostered a sense of accountability as each partner understood their role in achieving the collaborative objectives, but at the same time, it allowed them to track the progress easier, identify potential challenges and address any risks promptly and effectively. Further, the explicit definition of roles and responsibilities reduced conflicts and misunderstandings between the engaged parties.

Best Practice 5: Communication and Flexibility

The UBC can be fostered by communication and mutual trust among the involved parties. It was evident in our project that ensuring transparent communication between university and business representatives allowed for exchange of ideas and better adaptability to the LM needs. In addition, communication and flexibility between universities and businesses could further sustain CDDD in time as the universities could more swiftly respond to the evolving and fast changing LM demands, allowing for the curriculum to be concurrently updated. Still, effective communication and flexibility between university and business can be a driving force that transforms UBC beyond the learning experiences offered to students and graduates. Specifically, both parties, through their collaboration, are offered opportunities for achieving ground-breaking advancements that eventually could augment the institution's reputation and the business's competitiveness.

Best Practice 6: Monitoring and Evaluation

Monitoring the progress of the curriculum design, development, and delivery is of paramount importance. In the current project the monitoring mechanisms established, such as the regular progress reporting, the regular meetings where feedback among partners was shared and the quality assurance processes, allowed tracking the progress of the collaboration. In addition, the evaluation of the implemented curricula enabled us to monitor their effectiveness in terms of CT. Moreover, the evaluation stimulated the refinement process of the curriculum as well as of the collaboration and the roles of each party, per se. The refinement process was data-driven as the insight obtained during the evaluation ensured informed decision-making on behalf of the parties engaged in the collaboration.

Best Practice 7: Dissemination of best practices for the development of a community of practice

Sharing successful practices and outcomes with other universities and businesses can empower the development of a culture of collaboration and learning within academia and LM. Moreover, the knowledge exchange fosters innovation, encourages the adoption of effective strategies, and stimulates the development of new approaches. Hence, a community of practice [

51] with stakeholders from academia and LM that is constantly progressing and staying competitive will be developed. In our case, we are in the early stages of developing a network of academic and LM organisations invested in promoting CT. The network will allow universities and business stakeholders interested in joining the network to benchmark their own performance against other organisations’ standards or benefit from the knowledge and expertise of organisations already engaged in the network. Moreover, we consider that through the network, sharing successful practices and outcomes will enable the participating universities and businesses to extend their impact beyond their immediate sphere of influence to a broader audience of educational institutions and LM partners at a European or even global level. Ultimately, a community of practice might ensure that the overall quality of education and business practices regarding CT is enhanced.

4. Recommendations for future UBC initiatives

During the project’s lifecycle we have encountered many challenges and risks, we implemented various mitigation strategies, identified the strengths and weaknesses of the project, as well as the key success factors. This section aims at distilling the wisdom we garnered during the project offering a comprehensive set of recommendations, namely a set of guidelines that could be essential for the implementation of future UBC initiatives for CDDD particularly aiming at fostering CT or other soft skills. By embracing these recommendations, future UBC could become successful while implementing its initiatives in CDDD.

Recommendation 1: Build Strong Partnerships

We consider that effective UBC excels on the principle of synergy, namely the combined expertise, resources and perspectives of universities and businesses engaged in the partnership. However, for a partnership to stay strong throughout the implementation of an initiative, it is imperative to have clear objectives and long-term commitment from all parties [

6]. Therefore, a careful consideration of the partners included in the partnerships is crucial [

46]. Our experience revealed that business partners are highly engaged with plenty of activities, and it can be challenging to sustain their involvement and commitment in the partnership and its objectives. However, selecting LM partners that value UBC and recognize the importance of UBC can prove beneficial. Still, particular strategies such as the alignment of goals and objectives, the cultivation of long-term commitment and the sustainability of a culture of collaboration could further support the development of a strong partnership that can endure time. The partnership should be founded on a common vision and shared understanding. To meet this objective, the partnership can implement a series of meetings, team building activities and common training to allow for the academic and business parties to become acquainted, realise that the academic research priorities could be aligned with the LM demands and build a common language for communication. In that sense, the process of CDDD will be safeguarded for its scientific relevance and will be aligned with the real-world job requirements. Moreover, long-term commitment can be encouraged by the preparation of agreements and mutual understanding of the collaboration documents, such as the MoU. Such documents can directly describe the objectives, scope and expected outcomes of the partnership as well as the roles and responsibilities of the engaged entities. A culture of collaboration can be nurtured when parties cooperate, and principles such as transparency, inclusivity and equity are fostered.

Recommendation 2: Establish clear objectives for the collaboration

We further stress the importance of establishing clear objectives for UBC by formulating this second recommendation. There is extensive heterogeneity across the objectives of universities and businesses, rendering it difficult to achieve the necessary alignment required for successful collaboration [

47]. This was also proven by our own research [

25]. However, scholars highlight the importance of clear identification of objectives and motives for UBC for the successful implementation of partnerships [

46]. Among the benefits that this process provides is the mitigation of risks and misunderstandings between the engaged parties. Additionally, clear objectives allow for the establishment of measurable success and impact indicators, while facilitating decision-making throughout the partnership. To successfully implement this recommendation various activities can be implemented. First, representatives from both academia and LM should be engaged in a participatory process that will encourage collaborative needs analysis and requirements gathering. In the context of CDDD, this could mean that Universities and Businesses identify their needs and requirements for the design of a curriculum that is better aligned with the LM. Another activity that could foster the establishment of clear objectives is the implementation of common training between Universities and Business, which enhance collaborative and networked learning [

48]. Such an activity can guarantee the development of a clear communication and a common language among the parties and lead to the reciprocal identification of objectives for the partnership.

Recommendation 3: Design Transferable and Agile Curricula

Another recommendation that is a “lesson learned” from the current project but at the same time is reasonable in the context of CDDD is that UBC should remain flexible and willing to design transferable and adaptable curricula. One-size-fits-all curricula are not adequate to articulate with the existing differences that today’s evolution introduced in most professions. Knowledge and skills that are relevant today may become outdated tomorrow. It is imperative for UBC to respond swiftly to emerging trends, technological advancements and changing market demands. To implement this recommendation, an agile methodology for curriculum design could prove beneficial [53]. In particular, the LM can engage in the delivery of the curriculum and suggest emerging trends and topics that could be integrated into learning. If an agile design is followed, instructional approaches such as problem-based learning or case-based learning could prove beneficial. Such approaches allow for rapid updates and modifications in the course content to meet any emerging market demands, without requiring significant curricula modifications. Further, agile design methodology highlights that the design process is iterative and always leads to the refinement and redesign of a curriculum to better align with the LM’s and learners’ needs [

49]. The design of the curricula presented in the present study followed an agile approach as the curricula, after their first evaluation were refined and re-implemented. Finally, regular meetings and integration of feedback mechanisms, such as surveys or focus groups, can ensure ongoing collaboration and communication with LM partners. Hence, new skills gaps or areas of knowledge that should be integrated into the curricula could be identified more easily.

Recommendation 4: Reinforce experiential learning with real-work problems and cases studies

One aspect that was addressed by almost all curricula presented in the current study was the integration of real-work problems and case studies into the curricula to reinforce experiential learning and “bridge the gap” between academia and the LM. The problems and case studies were provided by the LM partners. Our research also identified that academia employed more traditional approaches (e.g., lectures) to learning and instruction as the emphasis was on theoretical concepts and construction of conceptual knowledge [

26]. Still, such traditional approaches are not endorsed by the LM and are less likely to promote soft skills, such as CT [

1]. Moreover, one benefit of bringing to the class authentic work situations, problems and case-studies is their contribution to maintaining students’ engagement and motivation [

48] but most importantly allows the student to perceive how the constructed knowledge will translate into the daily professional life and nurture the precocious development of a professional “way of acting”. This recommendation can be implemented through the participatory design of the curricula that requires the engagement of LM stakeholders, who will provide real-world challenges and case studies that align with the curricula ensuring relevance and authenticity. Moreover, the shift from more traditional instructional approaches to teaching methods such as project-based learning, problem-based learning or case-based learning can facilitate students solve problems and challenges that they might face while in the LM. Further, another valuable strategy that reinforces experiential learning is the integration of apprenticeships and internships into the curricula. Students' engagement with apprenticeships and internships immerses students in real-work environments and encourages the application of theoretical knowledge. Additionally, another strategy that fosters the implementation of the current recommendation is the integration of guest lectures or LM seminars into the curricula. LM representatives can share their experiences and case studies and foster the enrichment of the learning experiences providing insight into the complexities of professional life.

Recommendation 5: Implement Ongoing Evaluation

Our experience from the current project corroborates that evaluation is continuous and multidimensional at UBC. One dimension of evaluation in our project was the assessment of the results obtained in terms of students’ CT growth. Moreover, the effectiveness of the curricula was also evaluated through key performance indicators. Another dimension was the evaluation of the UBC per se, which was measured in different timestamps during the project’s lifecycle with measurable indicators. We consider this recommendation crucial as the evaluation allows stakeholders to measure the outcomes of the collaboration as well as the impact. Ongoing evaluation allows monitoring of the partnership’s progress against certain and jointly agreed milestones as well as uncovers potential risks and challenges that the partnership might face during the implementation of an initiative. Various strategies can be implemented to effectively implement this recommendation. For instance, as described earlier, the establishment of measurable key performance indicators can allow the partnership to monitor the progress but also the quality and impact of the outcomes obtained. It is essential for UBC to align the indicators with the objectives of the initiative. To monitor the indicators, regular meetings are required. In such meetings, stakeholders from universities and businesses should partake to facilitate discussions on progress, challenges, and suggestions for improvement. Another strategy to enhance continuous evaluation is to collect feedback from stakeholders such as students, faculty members, experts, and business representatives through focus groups, interviews, or surveys. In a future implementation of UBC for CDDD on CT, such activities should be further implemented. Finally, implementing longitudinal research designs to evaluate students’ employability and professional development would provide further input in the agile curriculum design process.