1. Introduction

In developing countries, the presence of slum areas is a major challenge (Sukmaniar, Pitoyo et al., 2021) because it leads to a slower growth rate with poorly organized settlements (Sik Lee & Anas, 1992). Consequently, developing countries need to promptly address slum settlements as a means to expedite economic growth. According to (Joshi et al., 2023), approximately one billion people worldwide are inhabitants of slum areas, and this poses a challenge to urbanization. The total population in slum settlements is projected to keep rising and expected to double by 2030 (Riley et al., 2007). This situation calls for significant concern, as the realization of these projections would entail a burgeoning population within slum settlements, coupled with a rise in the number of individuals experiencing impoverished economic conditions. High population density, poor services, and housing are features of slum areas. However, improved conditions (Bird et al., 2017) with basic urban services and sanitation can be seen in some urban areas (Bird et al., 2017; Gulyani & Talukdar, 2008). This situation is emblematic of the settlements found in developing countries, where there are several slum areas. Some parts of these areas has been successfully improved in respect to their social, physical, and economic sectors. Dense settlements in slum areas often result in limited space for waterways and drainage channels (Hogrewe et al., 1993). As a result, the occurrence of floods tend to jeopardize the dwellings of those residing in such settlements. Assuming the situation deteriorates further, there is a heightened risk of these homes collapsing. This is prevalent in virtually all urban area in developing countries. Effective sanitation interventions can lead to longer life expectancy, reduced health costs, and the prevention of various diseases (Jalan & Ravallion, 2001). Good sanitation management also has a positive impact on the health of infants and children (Haller et al., 2007). However, implementing sanitation and hygiene interventions is time-consuming, as they often require behavioral changes in addition to infrastructure improvements (Kar & Chambers, 2008). The process of achieving behavioral change takes time, specifically when it pertains to residents of slum settlements who have grown accustomed to neglecting cleanliness and health. Guiding them towards prioritizing these aspects demands a significant transformation. Building sanitation infrastructure also requires significant funding, which can be a limiting factor (Piesse, 2015). This highlights the need for the government to implement policies for enhancing sanitation. The emergence of conflicts and poor cooperation results in inadequate services, uneven infrastructure development (Sindt, 2007), as well as a decline in order and law (Islam, 2013). Conflicts tend to arise when there is lack of collaboration between the government and residents. Therefore, establishing strong collaboration becomes essential to maintain orderliness in infrastructural development. Urbanization continues due to the high migration of people to urban areas with increased economic activity (Sukmaniar, Kurniawan et al., 2020). This phenomenon is a result of the strong attraction that urban areas hold for migrants who aspire to enhance their social and economic conditions. These migrants hope their selected destination offers greater opportunities for them to achieve success. The high level of urbanization leads to a continuous rise in the development of urban areas (Kraas, 2007). This rise is in line with the increasing number of migrating populations, resulting in a heightened level of transactions involving both trade and services. Consequently, this trend is anticipated to impact the advancement of the economic sector.

In slum areas, households have a low socioeconomic mobility level between generations (Buckley & Kalarickal, 2005). This situation arises from the limited capabilities, often linked to lower education levels, which in turn hinders the residents ability to compete with those who are highly educated. As a result, their intergenerational socio-economic mobility remains significantly constrained. These areas are characterized by a lack of public services and home ownership security, a dense population (Golubchikov & Badyina, 2012), vulnerability to eviction and poor population status (Kim et al., 2019). Furthermore, unauthorized use of electricity and water is found in almost every location (Gulyani et al., 2010), inadequate basic services and several rented houses (Gulyani et al., 2018), as well as high vulnerability to diseases (Kangmennaang et al., 2020), are also prevalent. Shafie et al. (2013) stated that urban poor areas in developing countries have a high infant mortality rate, indicating lower infant life expectancy compared to rural areas (Bradley et al., 1992) where infant mortality is also higher. These diverse characteristics portrays the conditions of slum settlements across various regions in developing countries. This situation is deeply troubling, as failure to address these issues promptly could result in an increased number of infant deaths in urban slum settlements.

The Palembang city has a river called the Musi River, which divides it into two parts, namely the Ulu and Ilir areas. This division led to several settlements at the riverbanks (Putri et al., 2021), forming slum areas. Slum settlements are present in nearly every sub-district of Palembang City, but the most concentrated areas are found among residents living along the banks of the Musi River. Approximately one million people live in Palembang City, the province's capital and economic centre. Like other urban areas, this city always experiences an increase in population yearly (Sukmaniar, Pitoyo et al., 2020). This phenomenon stems from the bustling economic activities in Palembang City service and trade sectors. These factors attract migrants from both within and outside South Sumatra Province. Skilled migrants tend to settle in non-slum areas, while those without skills often reside in the low-cost settlements spread across Palembang. The combination of migrant influx and the pre-existing local population in these areas gives rise to various challenges, including poverty and crime. Studies on the distribution of slum areas in Palembang City using spatial data modelling on accuracy values are unavailable. Therefore, this novelty study aims to analyze the distribution of slum areas in Palembang City using spatial data modelling on accuracy value.

2. Literature Review

Population increase is a major source of slum areas (Sukmaniar, Kurniawan, et al., 2020), and the obstacles experienced by the inhabitants of these areas are in the socioeconomic and environmental aspects (Marx et al., 2013). The surge in population could be ascribed to both the uptick in native births and the arrival of migrants, primarily marked by a lower level of education. This educational deficiency hampers other aspects such as the economy and the environment. According to Duncker (2000), population density in slum areas affects the availability and quality of water infrastructure, cleanliness, and sanitation, with infrastructure investments often struggling to keep pace with rapid population growth. This situation emerges because of the government limitations in providing essential infrastructure for residents. Residents lack the means to independently establish the required infrastructure for their livelihoods. Furthermore, the growth rate of the total population in slum areas is typically faster than that of urban areas (Payne, 2005). A contributing factor is the role of family dynamics, wherein individuals living in urban areas promote their rural relatives to move to the city, aiming to enhance economic conditions. Several people in slum areas do not own a house (Gulyani et al., 2018), which makes rented houses predominant (Gulyani & Bassett, 2007), and infrastructure shortages are often observed (Hossain, 2012), thereby obstructing infrastructure development (Marx et al., 2013). The rented houses are indeed affordable, but unhabitable because they are constructed from materials such as wooden boards. A high number of urban poor and informal markets are features of slum areas (Gulyani et al., 2005), and these areas are also characterized by evictions (Murthy, 2012). Residents of slum settlements are primarily involved in menial occupations, which span across both trade and service industries. According to De Soto and Diaz (2002), other factors that contribute to lower eviction risks include inadequate facilities and poor health conditions (Marx et al., 2013). Evictions take place due to lack of land rights for the houses they have inhabited for years, along with poor health conditions caused by the excessive waste in the settlements. One of the prevalent diseases in these areas is tuberculosis. Unfortunately, slum areas often have high rates of disease (Duflo et al., 2012) leading to negative impacts on the mental health of the population (Asibey et al., 2021; Gruebner et al., 2011). The occurrence of stress among residents stemming from low incomes and inadequate facilities tend to impact their psychological well-being. Slum settlements tend to emerge in areas with numerous economic activities (Ezeh et al., 2017). Economic activities in slum settlements primarily comprises of informal economic endeavors. Other attributes include uninhabitable houses, poor environment (Sukmaniar, Kurniawan, et al., 2021), and difficulty accessing electricity and water (Fox, 2014). Residential buildings are not durable and common property rights are insecure (Lilford et al., 2017). Basic services and home ownership are needed by people in slum areas (Croese et al., 2016), and this includes settlement formalization (Nakamura, 2017), which enables land ownership, thereby stopping house renting (Huchzermeyer, 2008). Land ownership is a key effort made by inhabitants of slum areas in order to improve their quality of life (M. Bah et al., 2018). Land ownership is also an effective way to reduce poverty levels in slum areas (Garau & Sclar, 2004). It enables people to increase their business and investment (Quan, 2003), making it a crucial component for generating investment in slum areas (Deinlnger & Binswanger, 1999). By investing in the areas, residents can improve their environment and secure better housing (Kagawa, 2001), while also creating economic opportunities that lead to sustainable growth (Deininger, 2004). However, current land ownership certification processes mainly support the land market scope, which may not provide adequate security to those living below the poverty line against market forces (Haldrup, 2003). Most land in slum areas is owned by non-residents (Durand-Lasserve et al., 2009) who often sell land rights to urban residents, further fueling the growth and development this type of settlement (Bassett, 2007). To address these challenges, many studies recommend a coordinated approach to transform slum settlements into non-slum areas (Lobo et al., 2020; Lilford et al., 2017). It is also critical to note that the goal should not be to evict residents from slum settlements, but to transform them into better living conditions (Azhar et al., 2021).

3. Study area

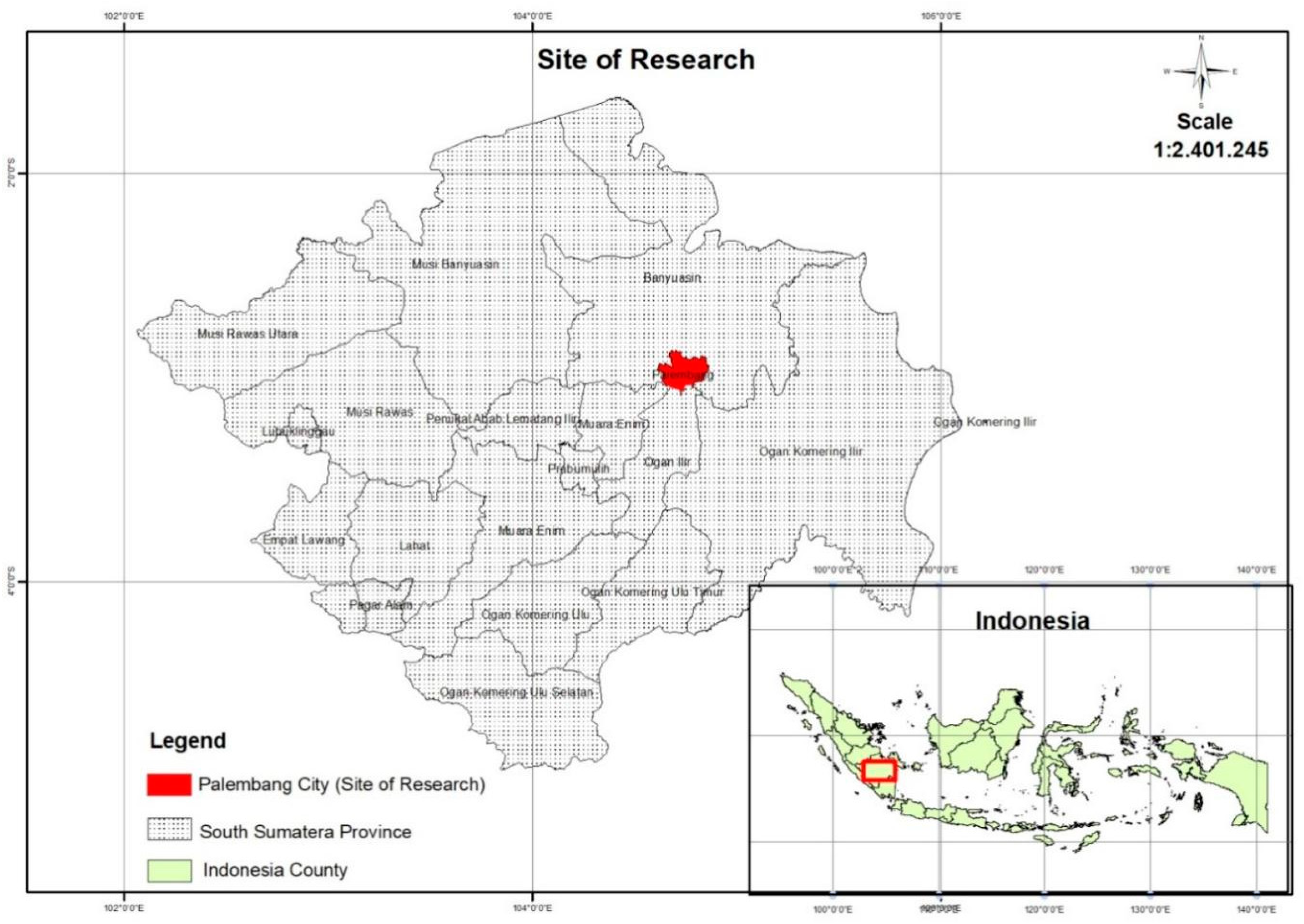

This study was carried out in Palembang City, the capital of South Sumatra Province, Indonesia. As the provincial capital, Palembang City is the centre of economic activities in the province, leading to a high migration of people into the city. This city was chosen as the study area due to the presence of slum areas. The existence of the Musi River in the city attracted numerous settlements at the river banks, which led to the formation of slum areas. The location of this study is shown in

Figure 1.

4. Methods

In this study, a quantitative method with a survey approach was used. It was conducted following several steps

: 1) Identifying the issue, which revolves around slum settlements in Palembang City. 2) Defining the study objective, by meticulously analyzing the distribution of the settlements in Palembang using spatial data modeling. 3) Using area proportional random sampling to select samples, ensuring a comparative representation across different settlements. 4) Selecting the tool for sample collection, namely GPS, to be used among families residing in the settlements. 5) Directly collecting data within the slum settlements. 6) The collected data were processed through GIS software, specifically ArcGIS, for the purpose of mapping. 7) The analyzed data were presented in the form of maps. This study employed various analysis techniques, including inverse distance weighted, kernel density, and spatial data modeling. The formula for inverse distance weighted is stated as follows (Azpurua & dos Ramos, 2010):

(

= 1,2,3,…, N) is N data height points, while

is a power parameter whose positive value can be changed, and is the distance from the point distribution to the interpolation point. In other words,

is a positive power value that can be changed, and

is calculated as follows:

The data were further analyzed using kernel density, an analysis of regional distribution patterns (Nanda et al., 2019) within a certain radius (Silverman, 2018). In conclusion, spatial data modelling with ROC analysis and AUC analysis were used for the accuracy of the slum distribution and summary of the accuracy of the slum distribution, respectively. The eighth step involved evaluating the results regarding the distribution of slum settlements and relating these findings to prior studies.

5. Findings and Discussion

5.1. Interpolation of slum distribution in Palembang City

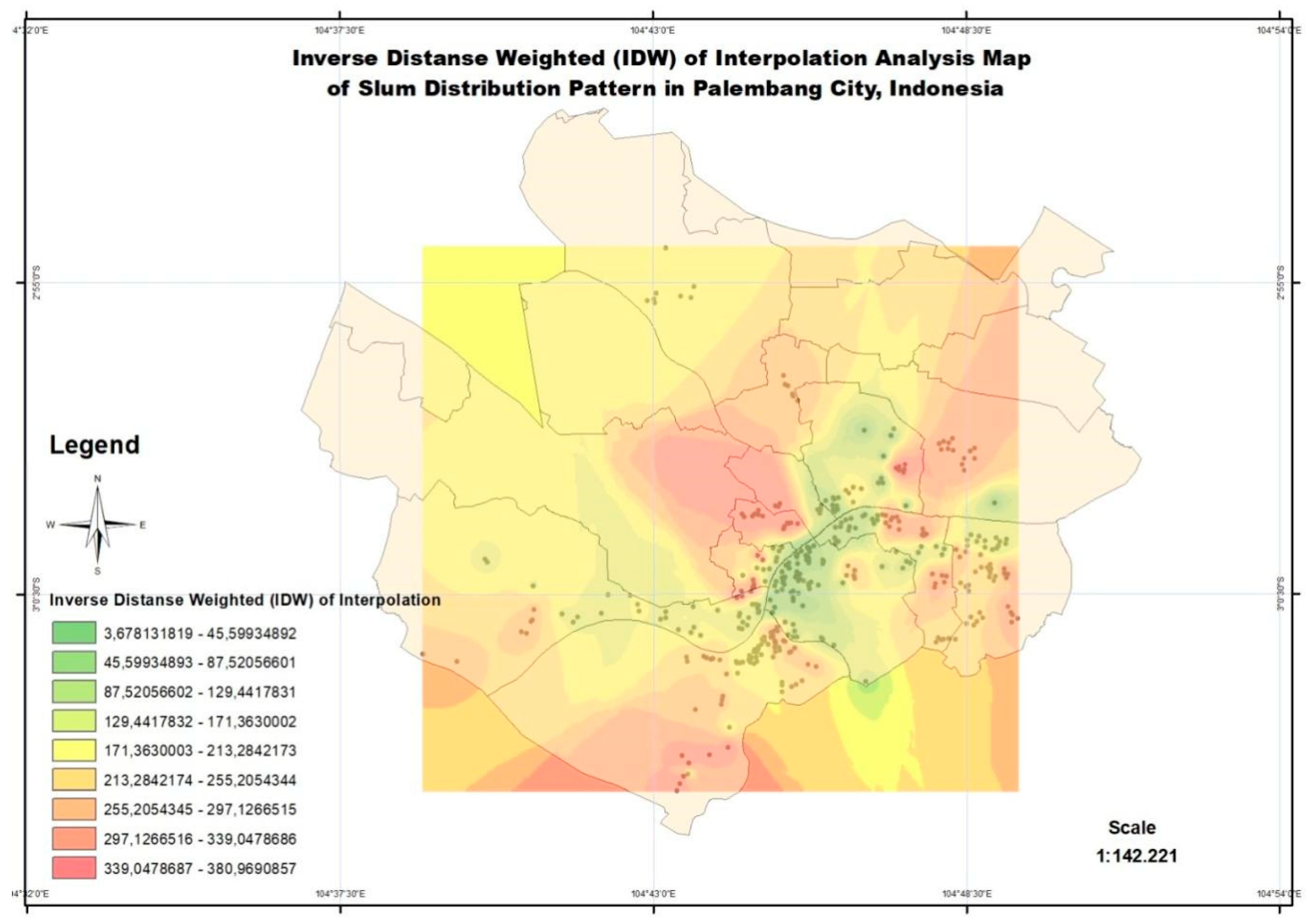

Interpolation of the slum distribution in Palembang City is seen in the population density of people living at the riverbanks. Additionally, it can be interpreted that the more populated the riverbank is, the denser the slum areas are and vice versa. The interpolation analysis of the distribution of slum areas in Palembang City through Inverse Distance Weighted (IDW) is shown in

Figure 2.

These results are used to study slum areas with poor water conditions, informal markets and many poor urban people (Gulyani et al., 2005). The water conditions are said to be poor because the river, the main source of water supply, is usually polluted by industrial and household waste. Furthermore, the presence of informal markets is due to the inability of the inhabitants to rent traditional markets, and those living in these areas are predominantly labourers and unemployed people. Slum areas are also synonymous with evictions (Murthy, 2012), which occur due to the illegal acquisition of lands. Low quality of life, poor buildings and environmental conditions are all characteristics of slum areas (Sukmaniar, Kurniawan, et al., 2021). The low quality of life is due to a weak economy, making it difficult for inhabitants to build decent houses and improve their environmental conditions. The government does not authorize people living in slum areas to settle in those areas because the lands are illegally occupied (Ghertner, 2008). However, the government finds it difficult to sanction and develop a relocation plan due to their long history of settlement in those areas.

Population growth constitutes a significant factor which contributes to the emergence of slum settlements in urban areas (Sukmaniar, Kurniawan, et al., 2020). This rapid population increase outpaces the availability of essential facilities and infrastructure, such as water, electricity, and basic amenities for residents (Duncker, 2000). The urban slum settlements experience a more rapid population surge compared to their rural counterparts (Payne, 2005). Residents of slum settlements encounter a plethora of challenges spanning environmental, social, and economic dimensions (Marx et al., 2013). Homelessness distinctly characterizes those living in slums (Gulyani et al., 2018), with rent becoming their primary means of residing in such areas (Gulyani & Bassett, 2007). The absence of various facilities and infrastructure is evident in slum settlements (Hossain, 2012), with constraints impeding the enhancement of these amenities (Marx et al., 2013). Informal markets and a dense concentration of urban poverty further characterizes the settlements (Gulyani et al., 2005). Evictions from living spaces also shape the lives of residents (Murthy, 2012), while the possession of land rights acts as a safeguard against forced ejections (De Soto & Diaz, 2002). Inadequate healthcare facilities leading to potential fatalities further typify those residing in the settlements (Marx et al., 2013).

5.2. Distribution pattern of slum areas through kernel density analysis

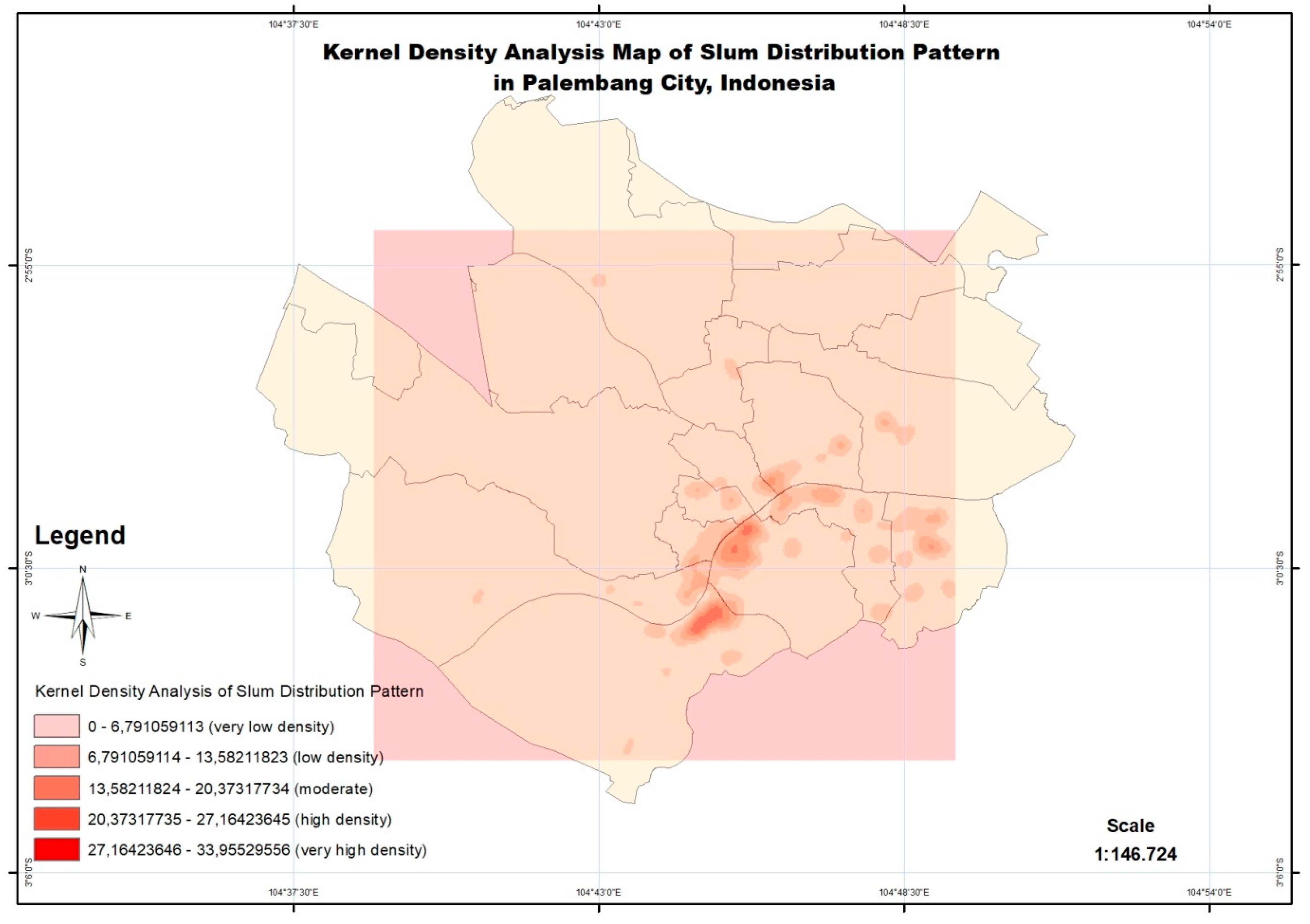

The distribution pattern of slum areas in Palembang City, through kernel density analysis as illustrated in

Figure 3, shows that the density of slum areas is spread along the Musi River, and the shape of the distribution is elongated along the river.

Figure 3 shows that the brighter the colour, the lower the density, while the more intense the colour, the higher the density.

Based on the findings of this study, the formation of slum areas can be attributed to the increase in population (Sukmaniar, Kurniawan, et al., 2020). The migration of people into Palembang City is caused by the need to experience a better economy. However, due to poor financial status, these people can only live in locations with affordable rent. They resort to settling in slum areas leading to a proliferation of these areas. High urban populations can be reduced by making poor services and slum conditions available in cities. This can deter people from migrating to cities (Feler & Henderson, 2011) but does not stop migrants completely from moving to urban areas for a better life.

Socioeconomic and environmental barriers are experienced by people in slum areas (Marx et al., 2013). The socioeconomic barriers are due to low financial ability or poor education, leading to the inability of the people to compete with those with higher skills or education. Meanwhile, environmental barriers occur because the people`s lifestyle is accustomed to a lack of care for the environment, such as littering, which worsens the slum area. Only a small proportion of people in slum areas can own a house (Gulyani et al., 2018), due to the low economic capacity of people in these areas. The inhabitants of slum areas do not have access to city infrastructure, such as good water, electricity, and sanitation (Fox, 2014). The relationship between water use and rent is a feature of these areas (Gulyani & Bassett, 2007).

Slum settlements serve as hotspots for innumerable diseases (Duflo et al., 2012). The mental health of residents could be influenced by poor environmental conditions (Asibey et al., 2021), resulting in compromised psychological well-being (Gruebner et al., 2011). The prevalence of informal economic activities is a defining trait of slums (Ezeh et al., 2017). Furthermore, adverse environmental factors such as garbage near residences and inadequate housing conditions (Sukmaniar, Kurniawan, et al., 2021), along with limited access to water and electricity (Fox, 2014), insecure land tenure, and non-durable building structures (Lilford et al., 2017), also characterize these areas. The residents in these areas are in dire need of essential services and proper housing (Croese et al., 2016). Formalized settlements (Nakamura, 2017), and land certification are necessary to transition from paying rents (Huchzermeyer, 2008). Ownership of land or houses in the settlements tend to significantly improve life quality (M. Bah et al., 2018). These also plays a crucial role in poverty alleviation in these areas (Garau & Sclar, 2004). Furthermore, land ownership is an approach to boost investment and business endeavors for slum residents (Quan, 2003).

5.3. Spatial Data Modeling Analysis on the slum areas distribution in Palembang City

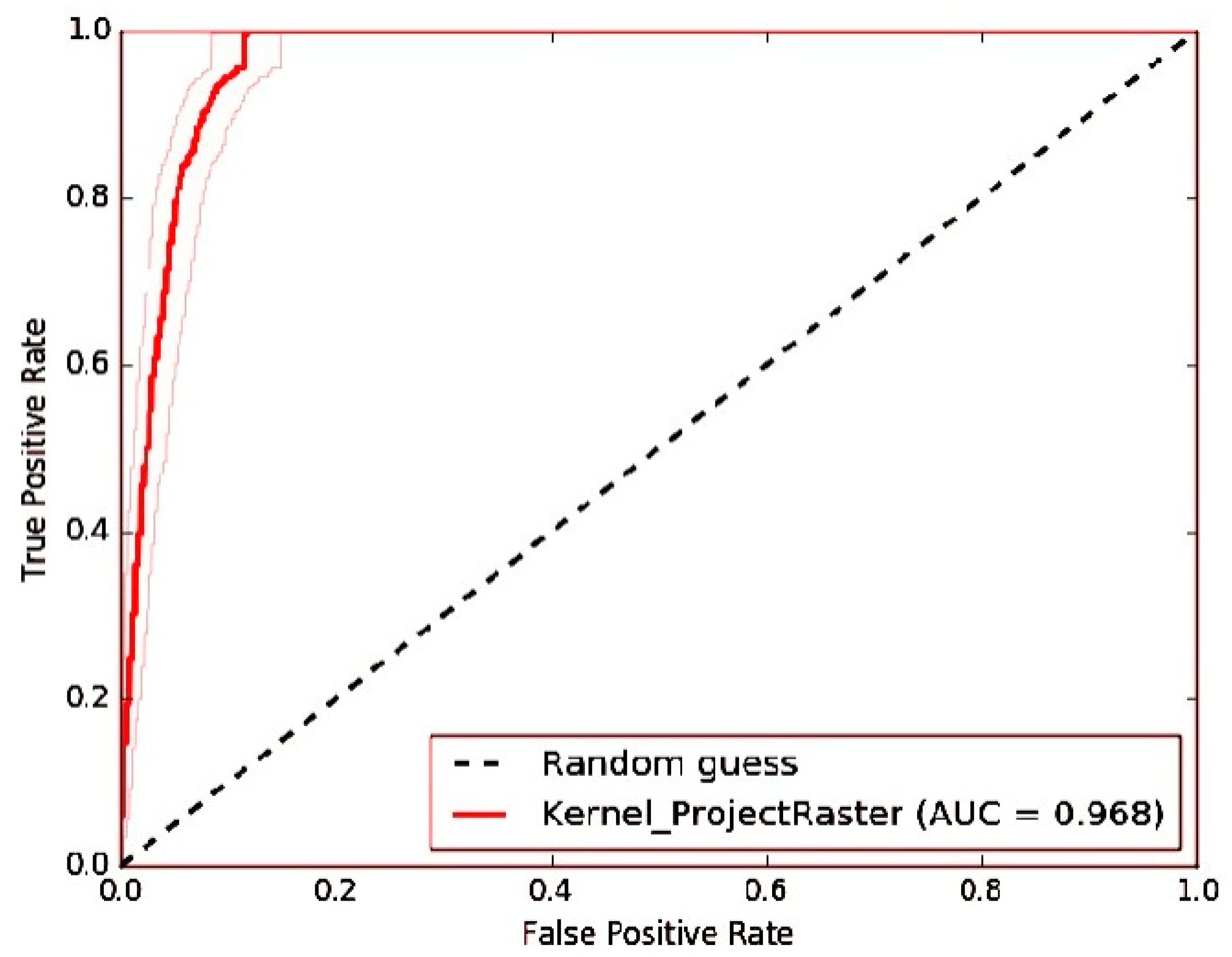

After kernel density analysis was carried out, spatial data modelling analysis was conducted for accuracy.

Figure 4 shows that the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) is at a true positive rate, indicating that the Area Under the Curve (AUC) is 96.8%. This is an excellent accuracy because the 96.8% value is in the range of >0.9-1 (AUC value,

Table 1). Furthermore, this means that the level of accuracy is high, and the test results prove that the density of slum distribution in Palembang City is spread along the Musi River. The results of Spatial Data Modeling through Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) and Area Under the Curve (AUC) is shown in

Figure 4.

Based on the results of this study, guaranteed land ownership need to be allocated to people living in slum areas in order to ensure improved living conditions (M. Bah et al., 2018). Furthermore, guaranteed land ownership eliminates the fear of future eviction. In improving slum areas, two considerations must be made, namely, providing basic services and formal or legal ownership (Croese et al., 2016). Basic services such as health and education are important for people in slum areas to ensure that their lives are improved socially and economically. Formal ownership is essential in order to avoid evictions leading to relocation.

The absence of land ownership rights in slum areas affects the improvement of infrastructure services in these areas (Marx et al., 2013). Slum upgrading can be performed by formalizing settlements and expanding land use (Nakamura, 2017). Settlement formalization is intended to improve people's lives in slum areas, thereby changing informal settlements into formal settlements. Land ownership in slum areas is of immense benefit because house renting is eliminated (Huchzermeyer, 2008). Therefore, the income earned by the people is channelled towards improved education, which leads to better job opportunities.

Land ownership holds significant importance for residents in slum settlements, because it enables land investment, ultimately improve their standard of living (Deinlnger & Binswanger, 1999). Those who have invested and earned higher incomes can access improved housing, setting them apart from other residents (Kagawa, 2001). In the settlements, land ownership fosters sustainable economic opportunities (Deininger, 2004), providing a lifeline for impoverished residents who require similar certificates to secure better livelihoods (Haldrup, 2003). However, the reality often involves non-residents of the settlements owning land in those regions (Durand-Lasserve et al., 2009). This situation could be exacerbated, as these landowners sell land rights to urban dwellers (Bassett, 2007). Coordinated strategies emerged as effective approaches to address the challenges posed by the settlements (Lobo et al., 2020), aiming to transform them into non-slum areas (Lilford et al., 2017). The transformation of slum settlements could be achieved without resorting to ejections, by comprehensively addressing all dimensions (Azhar et al., 2021).

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, the interpolation of the slum areas distribution in Palembang City is seen in the population density of people living on the river banks. The more populated the riverbanks are, the denser the slum areas and vice versa. The distribution pattern of slum areas in Palembang city through kernel density analysis showed that the form of the distribution is elongated along the river, and based on Spatial Data Modeling Analysis, the density of the slum distribution is spread along the Musi River. Therefore, to address these issues, several policies need to be implemented. Firstly, measures to anticipate population density are necessary to prevent social disasters such as land grabbing and natural disasters like floods. Secondly, the government should identify appropriate locations for immigrant settlement and collect data on immigrants at the neighborhood and village levels. Thirdly, training programs need to be provided to improve the skills of slum dwellers, enabling them to secure better jobs and higher incomes, and eventually transition to non-slum settlements. Fourthly, awareness campaigns should be conducted to promote environmental preservation, such as discouraging littering, to enhance the quality of life in slum settlements. This research is still limited to quantitative research, has not examined in depth qualitatively to determine the occurrence of population distribution and density in the slum settlements of Palembang City. Therefore, future research can be carried out using qualitative methods in order to obtain in-depth results related to the causes of population distribution and density in the slum settlements of Palembang City. Besides that, it can also combine quantitative methods with qualitative methods, namely mixed methods so that the results of the research are obtained in a comprehensive manner related to the distribution and density of population in the slum settlements of Palembang City.

References

- Asibey, M. O., Poku-Boansi, M., & Adutwum, I. O. (2021). Residential segregation of ethnic minorities and sustainable city development. Case of Kumasi, Ghana. Cities, 116(May 2020), 103297. [CrossRef]

- Azhar, A., Buttrey, H., & Ward, P. M. (2021). “Slumification” of Consolidated Informal Settlements: A Largely Unseen Challenge. Current Urban Studies, 09, 315–342. [CrossRef]

- Azpurua, M., & dos Ramos, K. (2010). A comparison of spatial interpolation methods for estimation of average electromagnetic field magnitude. Progress In Electromagnetics Research M, 14(January), 135–145. [CrossRef]

- Bassett, E. M. (2007). The Persistence of the Commons: Economic Theory and Community Decision-Making on Land Tenure in Voi, Kenya. African Studies Quarterly, 9(3), 1–29.

- Bird, J., Montebruno, P., & Regan, T. (2017). Life in a slum: Understanding living conditions in Nairobi’s slums across time and space. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 33(3), 496–520. [CrossRef]

- Bradley, D., Stephens, C., Harpham, T., & Cairncross, S. (1992). A Review of Environmental Health Impacts in Developing Country Cities. In The World Bank Washington, D.C. (Issue January 1992).

- Buckley, R. M., & Kalarickal, J. (2005). Housing policy in developing countries: Conjectures and refutations. World Bank Research Observer, 20(2), 233–257. [CrossRef]

- Croese, S., Cirolia, L. R., & Graham, N. (2016). Towards Habitat III: Confronting the disjuncture between global policy and local practice on Africa’s “challenge of slums.” Habitat International, 53, 237–242. [CrossRef]

- De Soto, H., & Diaz, H. P. (2002). The mystery of capital. Why capitalism triumphs in the West and fails everywhere else. In Canadian Journal of Latin American & Caribbean Studies (Vol. 27, Issue 53).

- Deininger, K. (2004). Land policies for growth and poverty reduction. In Choice Reviews Online (Vol. 41, Issue 09). [CrossRef]

- Deinlnger, K., & Binswanger, H. (1999). The Evolution of the World Bank’s Land Policy: Principles, Experience, and Future Challenges. The World Bank Research Observer, 14(2), 247–276. [CrossRef]

- Duflo, E., Galiani, S., & Mobarak, M. (2012). Improving Access to Urban Services for the Poor. Abdul Latif Jamelle Poverty Action Lab Report, October, 1–44. https://www.povertyactionlab.org/sites/default/files/publications/USI Review Paper.pdf.

- Duncker, L. C. (2000). Hygiene awareness for rural water supply and sanitation projects. In The Foundation for Water Research (Issue 819). http://www.fwr.org/wrcsa/819100.htm.

- Durand-Lasserve, A., Fernandes, E., Payne, G., & Rakodi, C. (2009). Social and economic impacts of land titling programs in urban and periurban areas: A short review of the literature. Urban Land Markets: Improving Land Management for Successful Urbanization, March, 133–161. [CrossRef]

- Ezeh, A., Oyebode, O., Satterthwaite, D., Chen, Y.-F., Ndugwa, R., Sartori, J., Mberu, B., Melendez-Torres, G. J., Haregu, T., Watson, S. I., Caiaffa, W., Capon, A., & Lilford, R. J. (2017). The history, geography, and sociology of slums and the health problems of people who live in slums. The Lancet, 389(10068), 547–558. [CrossRef]

- Feler, L., & Henderson, J. V. (2011). Exclusionary policies in urban development: Under-servicing migrant households in Brazilian cities. Journal of Urban Economics, 69(3), 253–272. [CrossRef]

- Fox, S. (2014). The Political Economy of Slums: Theory and Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. World Development, 54, 191–203. [CrossRef]

- Garau, P., & Sclar, E. D. (2004). Interim Report of the Task Force 8 on Improving the Lives of Slum Dwellers (Issue February).

- Ghertner, D. A. (2008). Analysis of new legal discourse behind Delhi’s slum demolitions. Economic and Political Weekly, 43(20), 57–66. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40277691.

- Golubchikov, O., & Badyina, A. (2012). Sustainable Housing for Sustainable Cities. In UN Habitat. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2194204.

- Gulyani, S., & Bassett, E. M. (2007). Retrieving the baby from the bathwater: Slum upgrading in Sub-Saharan Africa. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 25(4), 486–515. [CrossRef]

- Gulyani, S., & Talukdar, D. (2008). Slum Real Estate: The Low-Quality High-Price Puzzle in Nairobi’s Slum Rental Market and its Implications for Theory and Practice. World Development, 36(10), 1916–1937. [CrossRef]

- Gulyani, S., Talukdar, D., & Bassett, E. M. (2018). A sharing economy? Unpacking demand and living conditions in the urban housing market in Kenya. World Development, 109, 57–72. [CrossRef]

- Gulyani, S., Talukdar, D., & Jack, D. (2010). Poverty, living conditions, and infrastructure access: a comparison of slums in Dakar, Johannesburg, and Nairobi. World Bank Policy Research, July, 59. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1650479.

- Gulyani, S., Talukdar, D., & Kariuki, R. M. (2005). Universal (non)service? Water markets, household demand and the poor in urban Kenya. Urban Studies, 42(8), 1247–1274. [CrossRef]

- Haldrup, K. (2003). From Elitist Standards to Basic Needs – Diversified Strategies to Land Registration Serving Poverty Alleviation Objectives. 2nd FIG Regional Conference, 1–16.

- Haller, L., Hutton, G., & Bartram, J. (2007). Estimating the costs and health benefits of water and sanitation improvements at global level. Journal of Water and Health, 5(4), 467–480. [CrossRef]

- Hogrewe, W., Joyce, S., & Perez, E. (1993). The unique challenges of improving peri-urban sanitation. In WASH Technical Report No. 86 (Issue 86).

- Hossain, S. (2012). The production of space in the negotiation of water and electricity supply in a bosti of Dhaka. Habitat International, 36(1), 68–77. [CrossRef]

- Huchzermeyer, M. (2008). Slum upgrading in Nairobi within the housing and basic services market: A housing rights concern. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 43(1), 19–39. [CrossRef]

- Islam, N. (2013). Urban Governance In Bangladesh: The Post Independence Scenario. Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bangladesh (Hum.), 58(2), 289–301.

- Jalan, J., & Ravallion, M. (2001). Does piped water reduce diarrhea for children in rural India? In Policy Research Working Paper 2664. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, N., Gerlak, A. K., Hannah, C., Lopus, S., Krell, N., & Evans, T. (2023). Water insecurity, housing tenure, and the role of informal water services in Nairobi’s slum settlements. World Development, 164, 106165. [CrossRef]

- Kagawa, A. (2001). Policy Effects and Tenure Security Perceptions of Peruvian Urban Land Tenure Regularisation Policy in the 1990s. ESF/N-AERUS International Workshop, 23, 1–12.

- Kangmennaang, J., Bisung, E., & Elliott, S. J. (2020). ‘We Are Drinking Diseases’: Perception of Water Insecurity and Emotional Distress in Urban Slums in Accra, Ghana. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Kar, K., & Chambers, R. (2008). Handbook on Community-Led Total Sanitation. In Children (Vol. 44, Issue 0). http://www.communityledtotalsanitation.org/sites/communityledtotalsanitation.org/files/cltshandbook.pdf.

- Kim, H. S., Yoon, Y., & Mutinda, M. (2019). Secure land tenure for urban slum-dwellers: A conjoint experiment in Kenya. Habitat International, 93(November 2018), 102048. [CrossRef]

- Kraas, F. (2007). Megacities and Global Change in East , Southeast and South Asia. ASIEN, 103(April), 9–22.

- Lilford, R. J., Oyebode, O., Satterthwaite, D., Melendez-Torres, G. J., Chen, Y. F., & Mberu, B. (2017). Improving the Health and Welfare of People who Live in Slums. The Lancet, 389(10068), 559–570.

- Lobo, J., Alberti, M., & Allen-Dumas, M. (2020). Urban Science: Integrated Theory from the First Cities to Sustainable Metropolises. SSRN Electronic Journal, January. [CrossRef]

- M. Bah, E., Faye, I., & F. Geh, Z. (2018). Housing market dynamics in Africa. In Regional Science and Urban Economics. Springer Nature. [CrossRef]

- Marx, B., Stoker, T., & Suri, T. (2013). The economics of slums in the developing world. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27(4), 187–210. [CrossRef]

- Murthy, S. L. (2012). Land security and the challenges of realizing the human right to water and sanitation in the slums of Mumbai, India. Health and Human Rights, 14(2), 61–73. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40277691.

- Nakamura, S. (2017). Does slum formalisation without title provision stimulate housing improvement? A case of slum declaration in Pune, India. Urban Studies, 54(7), 1715–1735. [CrossRef]

- Nanda, C. A., Nugraha, A. L., & Firdaus, H. S. (2019). Analisis Tingkat Daerah Rawan Kriminalitas Menggunakan Metode Kernel Density Di Wilayah Hukum Polrestabes Kota Semarang. Jurnal Geodesi Undip, 8(4), 50–58. https://ejournal3.undip.ac.id/index.php/geodesi/article/viewFile/25144/22354.

- Payne, G. (2005). Getting ahead of the game: A twin-track approach to improving existing slums and reducing the need for future slums. Environment and Urbanization, 17(1), 135–146. [CrossRef]

- Piesse, M. (2015). Water Security in Urban India: Water Supply and Human Health. In Future Directions International (Issue September). http://futuredirections.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Water_Security_in_Urban_India_Water_Supply_and_Human_Health.pdf.

- Putri, M. K., Nuranisa, N., Mei, E. T. W., Giyarsih, S. R., Sukmaniar, S., & Saputra, W. (2021). The characteristics of ethnics people at the banks of musi river in palembang. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 683(1). [CrossRef]

- Quan, J. (2003). Reflections on the Development Policy Environment For Land and Property Rights, 1997–2003: Vol. Oktober.

- Riley, L. W., Ko, A. I., Unger, A., & Reis, M. G. (2007). Slum health: Diseases of neglected populations. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 7(2), 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Shafie, F. A., Omar, D., & Karuppannan, S. (2013). Environmental Health Impact Assessment and Urban Planning. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 85, 82–91. [CrossRef]

- Sik Lee, K., & Anas, A. (1992). Costs of Deficient Infrastructure: The Case of Nigerian Manufacturing. Urban Studies, 29(7), 1071–1092. [CrossRef]

- Silverman, B. W. (2018). Density Estimation for Statistics and Data Analysis. Technometrics, 29(4), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Sindt, R. P. (2007). Housing Economics: The Condominium Market in Transition. Regional Business Review, 26, 59–71.

- 55. Sukmaniar, Kurniawan, A., & Pitoyo, A. J. (2021). Hazard Level of Slum Areas in Palembang City. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 884(1), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- 56. Sukmaniar, Kurniawan, A., & Pitoyo, A. J. (2020). Population characteristics and distribution patterns of slum areas in Palembang City: Getis ord gi∗ analysis. E3S Web of Conferences, 200, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- 57. Sukmaniar, Pitoyo, A. J., & Kurniawan, A. (2020). Vulnerability of economic resilience of slum settlements in the City of Palembang. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 451(1). [CrossRef]

- 58. Sukmaniar, Pitoyo, A. J., & Kurniawan, A. (2021). Deviant behaviour in the slum community of Palembang city. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 683(1), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Sukmaniar, Saputra, W., & Taufik, M. (2022). Analisis Spasial Pola Persebaran Kepadatan Penduduk di Permukiman Kumuh Kota Palembang Melalui Kernel Density. In Laporan Hasil Penelitian Universitas PGRI Palembang.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).