Submitted:

12 March 2024

Posted:

14 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Machiavellianism

1.2. “Bullshit” and “Bullshitting”

1.3. Moderation by Verbal Reasoning

1.4. Current Research and Hypotheses

2. Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Verbal Reasoning

2.2.2. Machiavellianism

2.2.3. “Bullshitting” Frequency

2.3. Analytical Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Overall Fit of the Latent Models

3.2. Hypothesis Testing

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of the Present Study

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

4.3. Conclusion

References

- Blötner, C.; Bergold, S. To be fooled or not to be fooled. Approach and avoidance facets of Machiavellianism. Psychol. Assess. 2022, 34, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blötner, C.; Bergold, S. It is double pleasure to deceive the deceiver: Machiavellianism is associated with producing but not necessarily with falling for bullshit. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 62, 467–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boccio, C.M.; Beaver, K.M.; Schwartz, J.A. The role of verbal intelligence in becoming a successful criminal: Results from a longitudinal sample. Intelligence 2018, 66, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, R.; Geis, F.L. Studies in Machiavellianism; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Condon, D.M.; Revelle, W. The international cognitive ability resource: Development and initial validation of a public-domain measure. Intelligence 2014, 43, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debey, E.; Ridderinkhof, R.K.; De Houwer, J.; De Schryver, M.; Verschuere, B. Suppressing the truth as a mechanism of deception: Delta plots reveal the role of response inhibition in lying. Conscious. Cogn. 2015, 37, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouvelis, M.; Pearce, G. Is there a link between intelligence and lying? J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2023, 206, 182–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaad, E.; Hanania, S.B.; Mazor, S.; Zvi, L. The relations between deception, narcissism and self-assessed lie- and truth-related abilities. Psychiatry Psychol. Law 2020, 27, 880–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnthorsdottir, A.; McCabe, K.; Smith, V. Using the Machiavellianism instrument to predict trustworthiness in a bargaining game. J. Econ. Psychol. 2002, 23, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, W.; Breeden, C.J.; Lambert, J.; Kinrade, C. Dark Triad constructs blend facets with heterogenous self-presentation tactic use profiles. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2022, 184, 111193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.-T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, T.D.; Pornprasertmanit, S.; Schoemann, A.M.; Rosseel, Y.; Miller, P.; Quick, C.; Garnier-Villarreal, M.; Selig, J.; Boulton, A.; Preacher, K.; Coffman, D.; Rhemtulla, M.; Robitzsch, A.; Enders, C.; Arslan, R.; Clinton, B.; Panko, P.; Merkle, E.; Chesnut, S.; Byrnes, J.; Johnson, A.R. semTools: Useful tools for structural equation modeling; R package version 0.5–6; CRAN: 2022. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=semTools.

- Little, T.D.; Bovaird, J.A.; Widaman, K.F. On the merits of orthogonalizing powered and product terms: Implications for modeling interactions among latent variables. Struct. Equ. Model. 2006, 13, 497–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littrell, S.; Fugelsang, J.A. Bullshit blind spots: The roles of miscalibration and information processing in bullshit detection. Thinking and Reasoning. [CrossRef]

- Littrell, S.; Risko, E.F.; Fugelsang, J.A. The Bullshitting Frequency Scale: Development and psychometric properties. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 60, 248–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michels, M. General intelligence and the Dark Triad: A meta-analysis. J. Individ. Differ. 2022, 43, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michels, M.; Molz, G.; Maas genannt Bermpohl, F. The ability to lie and its relations to the Dark Triad and general intelligence. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 166, 110195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neisser, U.; Boodoo, G.; Bouchard, T.J.; Jr Boykin, A.W.; Brody, N.; Ceci, S.J.; Halpern, D.F.; Loehlin, J.C.; Perloff, R.; Sternberg, R.J.; Urbina, S. Intelligence: Knowns and unknowns. Am. Psychol. 1996, 51, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomäki, J.; Yan, J.; Laakasuo, M. Machiavelli as a poker mate–A naturalistic behavioural study on strategic deception. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 98, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G.; Cheyne, J.A.; Barr, N.; Koehler, D.J.; Fugelsang, J.A. On the reception and detection of pseudo-profound bullshit. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2015, 10, 549–563, Pornprasertmanit, S., Miller, P., Schoemann, A., Jorgensen, T. D. (2021). simsem: SIMulated Structural Equation Modeling (R package version 0.5–16). CRAN. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=simsem.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarzyńska, J.; Falkiewicz, M.; Riegel, M.; Babula, J.; Margulies, D.S.; Nęcka, E.; Grabowska, A.; Szatkowska, I. More intelligent extraverts are more likely to deceive. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarzyńska-Wawer, J.; Hanusz, K.; Pawlak, A.; Szymanowska, J.; Wawer, A. Are intelligent people better liars? Relationships between cognitive abilities and credible lying. J. Intell. 2023, 11, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutin, A.R.; Stephan, Y.; Luchetti, M.; Strickhouser, J.E.; Aschwanden, D.; Terracciano, A. The association between Five Factor model personality traits and verbal and numeric reasoning. Neuropsychol. Dev. Cognition. Sect. B Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 2022, 29, 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touhey, J.C. Intelligence, Machiavellianism and social mobility. Br. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1973, 12, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turi, A.; Rebeleș, M.-R.; Visu-Petra, L. The tangled webs they weave: A scoping review of deception detection and production in relation to Dark Triad traits. Acta Psychol. 2022, 226, 103574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turpin, M.H.; Kara-Yakoubian, M.; Walker, A.C.; Walker HE, K.; Fugelsang, J.A.; Stolz, J.A. Bullshit ability as an honest signal of intelligence. Evol. Psychol. 2021, 19, 14747049211000317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volbert, R.; Steller, M.; Galow, A. Das Glaubhaftigkeitsgutachten [Credibility assessment] In Handbuch der Forensischen Psychiatrie. Band 2: Psychopathologische Grundlagen und Praxis der Forensischen Psychiatrie im Strafrecht [Handbook of forensic psychiatry. Volume 2: Psychopathological basics and practice of forensic psychiatry in criminal justice]; Kröber, H.-L., Dölling, D., Leygraf, N., Sass, H., Eds.; Darmstadt, 2010; pp. 623–689.

- Vrij, A.; Granhag, P.A.; Mann, S. Good liars. J. Psychiatry Law 2010, 38, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissing, B.G.; Reinhard, M.A. The Dark Triad and deception perceptions. Frontiers in Psychology, 1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Approach | Avoidance | Persuasive BS | Evasive BS | VR | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avoidance | .43 | — | ||||

| Persuasive BS | .39 | .28 | — | |||

| Evasive BS | .15 | .17 | .47 | — | ||

| VR | .02 | .02 | -.05 | .08 | ||

| Age | -.04 | -.04 | -.14 | -.20 | -.03 | |

| Gender | .02† | .02† | .002† | .006† | .02† | .005† |

| Model | χ2 | df | CFI | RMSEA [95% CI] | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmatory factor analysis of all items | 548.48 | 242 | .92 | .05 [.04, .06] | .05 |

| Approach x Verbal Reasoning — Persuasive “Bullshitting” | |||||

| Main effects | 244.14 | 101 | .94 | .05 [.04, .06] | .04 |

| Main effects plus interaction effect | 303.43 | 164 | .95 | .04 [.03, .05] | .04 |

| Avoidance x Verbal Reasoning — Evasive “Bullshitting” | |||||

| Main effects | 119.22 | 51 | .94 | .05 [.04, .06] | .05 |

| Main effects plus interaction effect | 149.21 | 98 | .96 | .03 [.02, .04] | .04 |

| Note. df = Degrees of freedom. CFI = Comparative fit index. RMSEA = Root mean square error of approximation. SRMR = Square root mean residual. All models included verbal reasoning as a moderator. | |||||

| Persuasive “Bullshitting” | Evasive “Bullshitting” | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Main effects | Main effects plus interaction | Main effects | Main effects plus interaction |

| Approach | .44 [.36, .53] | .44 [.36, .53] | — | — |

| Avoidance | — | — | .25 [.15, .36] | .26 [.15, .36] |

| Verbal Reasoning | -.10 [-.22, .02] | -.10 [-.22, .02] | .11 [-.02, .24] | .11 [-.02, .25] |

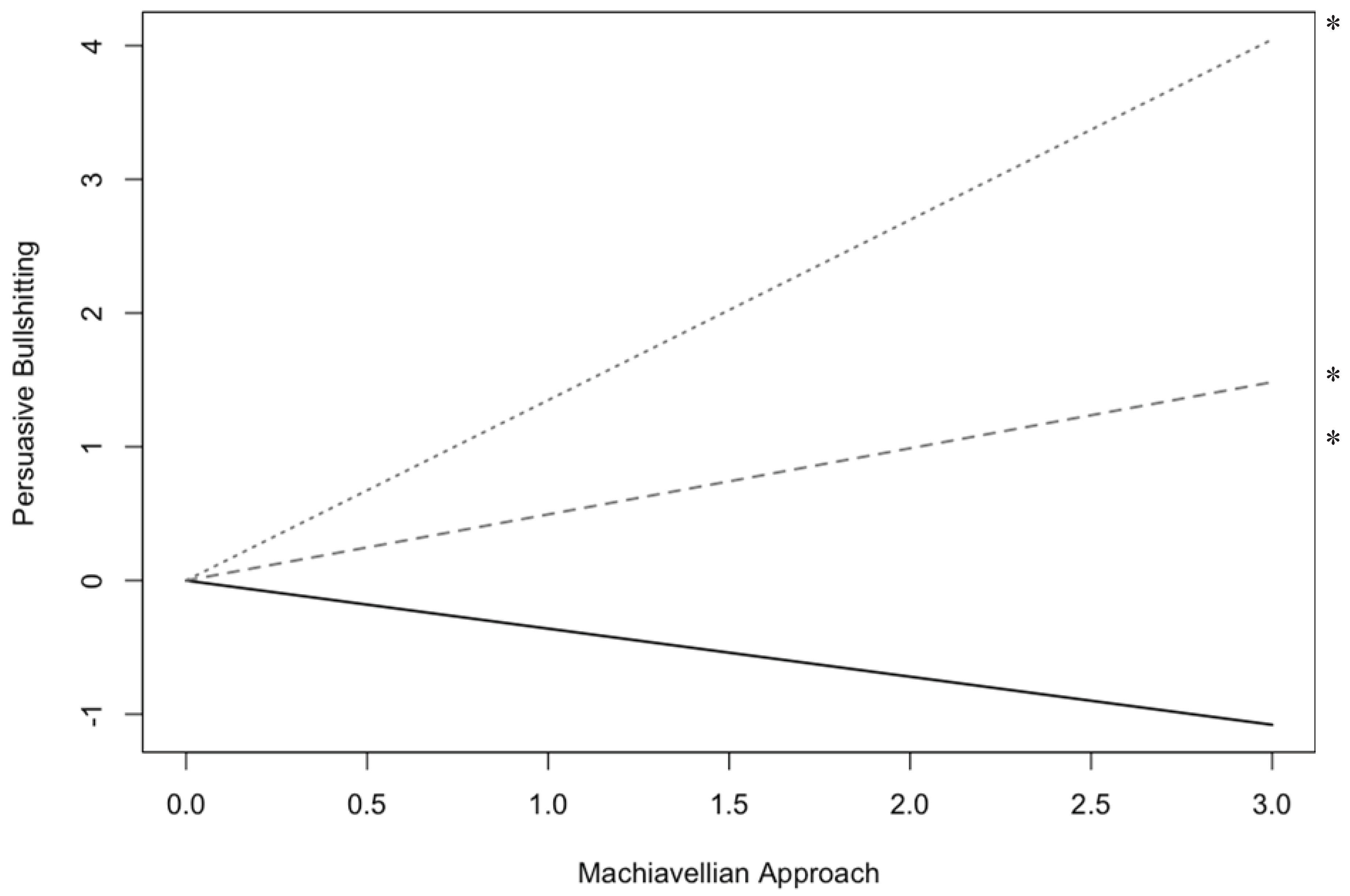

| Interaction | — | .22 [.07, .38] | — | .10 [-.04, .24] |

| ρMach-VR | .05 [-.08 , .18] | .05 [-.08, .18] | .05 [-.09, .18] | .05 [-.09, .18] |

| R2 | .203 | .253 | .080 | .089 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).