Submitted:

30 August 2023

Posted:

31 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Survey

2.2. Consensus meeting

3. Results

3.1. Survey

3.2. Statements

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, B.; Nagai, S.; Armitage, J.O.; Witherspoon, B.; Nabhan, C.; Godwin, A.C.; Yang, Y.T.; Kommalapati, A.; Tella, S.H.; DeAngelis, C.; et al. Regulatory and Clinical Experiences with Biosimilar Filgrastim in the U.S., the European Union, Japan, and Canada. Oncologist 2019, 24, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solitano, V.; D’Amico, F.; Da Rio, L.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Danese, S. The European Perspective and History on Biosimilars for the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Crohns Colitis 360 2021, 3, otab012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danese, S.; Gomollon, F.; Governing, B.; Operational Board of, E. ECCO position statement: the use of biosimilar medicines in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). J Crohns Colitis 2013, 7, 586–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, D.; Mishra, R.K.; Pandey, R. Biosimilars: Current regulatory perspective and challenges. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2013, 5, 80–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Declerck, P.; Farouk-Rezk, M.; Rudd, P.M. Biosimilarity Versus Manufacturing Change: Two Distinct Concepts. Pharm Res 2016, 33, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desanvicente-Celis, Z.; Gomez-Lopez, A.; Anaya, J.M. Similar biotherapeutic products: overview and reflections. Immunotherapy 2012, 4, 1841–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danese, S.; Fiorino, G.; Michetti, P. Viewpoint: knowledge and viewpoints on biosimilar monoclonal antibodies among members of the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization. J Crohns Colitis 2014, 8, 1548–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernasko, N.; Clarke, K. Why Is There Low Utilization of Biosimilars in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients by Gastroenterology Advanced Practice Providers? Crohns Colitis 360 2021, 3, otab004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solitano, V.; D’Amico, F.; Fiorino, G.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Danese, S. Biosimilar switching in inflammatory bowel disease: from evidence to clinical practice. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2020, 16, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; Solitano, V.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Danese, S. Nocebo effect and biosimilars in inflammatory bowel diseases: what’s new and what’s next? Expert Opin Biol Ther 2021, 21, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltz, R.M.; McClinchie, M.G.; Boyle, B.M.; McNicol, M.; Morris, G.A.; Crawford, E.C.; Moses, J.; Kim, S.C. Biosimilars for Pediatric Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Pediatric Gastroenterology Clinical Practice Survey. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2023, 76, 616–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, H.; Beydoun, D.; Chien, D.; Lessor, T.; McCabe, D.; Muenzberg, M.; Popovian, R.; Uy, J. Awareness, Knowledge, and Perceptions of Biosimilars Among Specialty Physicians. Adv Ther 2017, 33, 2160–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Minh Duc, N.T.; Luu Lam Thang, T.; Nam, N.H.; Ng, S.J.; Abbas, K.S.; Huy, N.T.; Marusic, A.; Paul, C.L.; Kwok, J.; et al. A Consensus-Based Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies (CROSS). J Gen Intern Med 2021, 36, 3179–3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, E.J.; Fedorak, R.N.; Jairath, V. Systematic Review: Non-medical Switching of Infliximab to CT-P13 in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Dig Dis Sci 2020, 65, 2354–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Beloso, N.; Altabas-Gonzalez, I.; Samartin-Ucha, M.; Gayoso-Rey, M.; De Castro-Parga, M.L.; Salgado-Barreira, A.; Cibeira-Badia, A.; Pineiro-Corrales, M.G.; Gonzalez-Vilas, D.; Pego-Reigosa, J.M.; et al. Switching between reference adalimumab and biosimilars in chronic immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: A systematic literature review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2022, 88, 1529–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Lonnfors, S.; Roblin, X.; Danese, S.; Avedano, L. Patient Perspectives on Biosimilars: A Survey by the European Federation of Crohn’s and Ulcerative Colitis Associations. J Crohns Colitis 2017, 11, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghnejad, V.; Le Berre, C.; Dominique, Y.; Zallot, C.; Guillemin, F.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Impact of a medical interview on the decision to switch from originator infliximab to its biosimilar in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis 2020, 52, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, K.K.; Olsen, I.C.; Goll, G.L.; Lorentzen, M.; Bolstad, N.; Haavardsholm, E.A.; Lundin, K.E.A.; Mork, C.; Jahnsen, J.; Kvien, T.K.; et al. Switching from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 compared with maintained treatment with originator infliximab (NOR-SWITCH): a 52-week, randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 2304–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanauer, S.; Liedert, B.; Balser, S.; Brockstedt, E.; Moschetti, V.; Schreiber, S. Safety and efficacy of BI 695501 versus adalimumab reference product in patients with advanced Crohn’s disease (VOLTAIRE-CD): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021, 6, 816–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gros, B.; Plevris, N.; Constantine-Cooke, N.; Lyons, M.; O’Hare, C.; Noble, C.; Arnott, I.D.; Jones, G.R.; Lees, C.W.; Derikx, L. Multiple infliximab biosimilar switches appear to be safe and effective in a real-world inflammatory bowel disease cohort. United European Gastroenterol J 2023, 11, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, S.; Piazza, O.S.N.; Conforti, F.S.; Fasci, A.; Rimondi, A.; Marinoni, B.; Casini, V.; Ricci, C.; Munari, F.; Pirola, L.; et al. Safety and clinical efficacy of the double switch from originator infliximab to biosimilars CT-P13 and SB2 in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (SCESICS): A multicenter cohort study. Clin Transl Sci 2022, 15, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trystram, N.; Abitbol, V.; Tannoury, J.; Lecomte, M.; Assaraf, J.; Malamut, G.; Gagniere, C.; Barre, A.; Sobhani, I.; Chaussade, S.; et al. Outcomes after double switching from originator Infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 and biosimilar SB2 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a 12-month prospective cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2021, 53, 887–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmmod, S.; Schultheiss, J.P.D.; van Bodegraven, A.A.; Dijkstra, G.; Gilissen, L.P.L.; Hoentjen, F.; Lutgens, M.; Mahmmod, N.; van der Meulen-de Jong, A.E.; Smits, L.J.T.; et al. Outcome of Reverse Switching From CT-P13 to Originator Infliximab in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2021, 27, 1954–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papamichael, K.; Afif, W.; Drobne, D.; Dubinsky, M.C.; Ferrante, M.; Irving, P.M.; Kamperidis, N.; Kobayashi, T.; Kotze, P.G.; Lambert, J.; et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring of biologics in inflammatory bowel disease: unmet needs and future perspectives. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022, 7, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papamichael, K.; Stocco, G.; Ruiz Del Agua, A. Challenges in Therapeutic Drug Monitoring: Optimizing Biological Treatments in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Other Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Diseases. Ther Drug Monit 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.H.; Solitano, V.; Vuyyuru, S.K.; MacDonald, J.K.; Syversen, S.W.; Jorgensen, K.K.; Crowley, E.; Ma, C.; Jairath, V.; Singh, S. Proactive Therapeutic Drug Monitoring Versus Conventional Management for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology 2022, 163, 937–949 e932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lontai, L.; Gonczi, L.; Balogh, F.; Komlodi, N.; Resal, T.; Farkas, K.; Molnar, T.; Miheller, P.; Golovics, P.A.; Schafer, E.; et al. Non-medical switch from the originator to biosimilar and between biosimilars of adalimumab in inflammatory bowel disease - a prospective, multicentre study. Dig Liver Dis 2022, 54, 1639–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamfers M, V.A.G.; Leenstra, S.; Venkatesan, S. Overview of the patent expiry of (non-)tyrosine kinase inhibitors approved for clinical use in the EU and the US. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal) 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.S.; Ehrenpreis, E.D.; Kulkarni, P.M.; Gastroenterology, F.D.-R.M.C.o.t.A.C.o. Biosimilars: the need, the challenge, the future: the FDA perspective. Am J Gastroenterol 2014, 109, 1856–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, V.; Mytych, D.T.; Das, S.; Franklin, J. Pharmacokinetic Similarity of ABP 654, an Ustekinumab Biosimilar Candidate: Results from a Randomized, Double-blind Study in Healthy Subjects. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogler, G.; Singh, A.; Kavanaugh, A.; Rubin, D.T. Extraintestinal Manifestations of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Current Concepts, Treatment, and Implications for Disease Management. Gastroenterology 2021, 161, 1118–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Boland, B.S.; Jess, T.; Moore, A.A. Management of inflammatory bowel diseases in older adults. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023, 8, 368–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; Fiorino, G.; Furfaro, F.; Allocca, M.; Roda, G.; Loy, L.; Zilli, A.; Solitano, V.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Danese, S. Patient’s profiling for therapeutic management of inflammatory bowel disease: a tailored approach. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020, 14, 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, M.; Garg, V.; Wu, E.Q.; Wang, J.; Skup, M. Economic Impact of Non-Medical Switching from Originator Biologics to Biosimilars: A Systematic Literature Review. Adv Ther 2019, 36, 1851–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

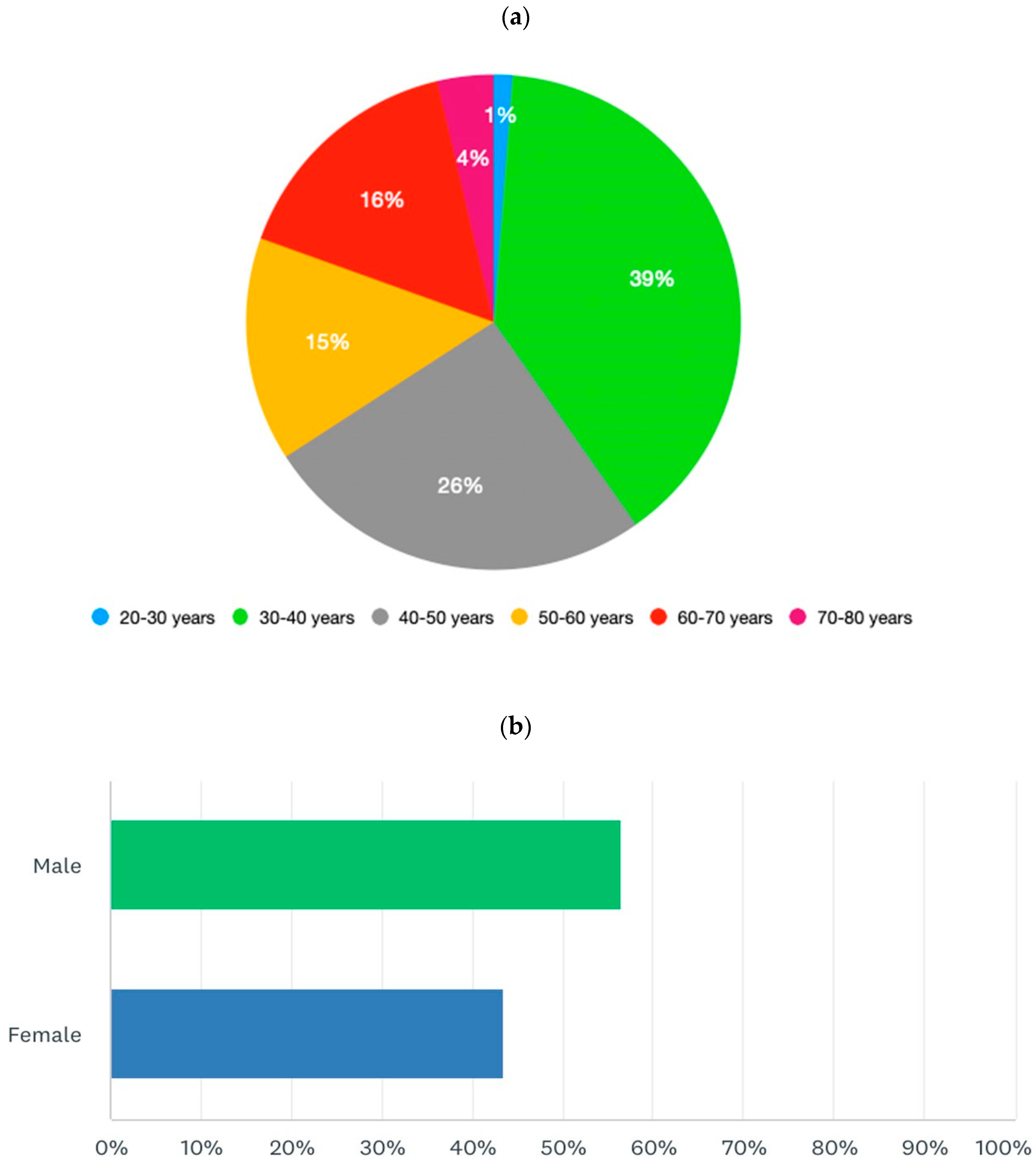

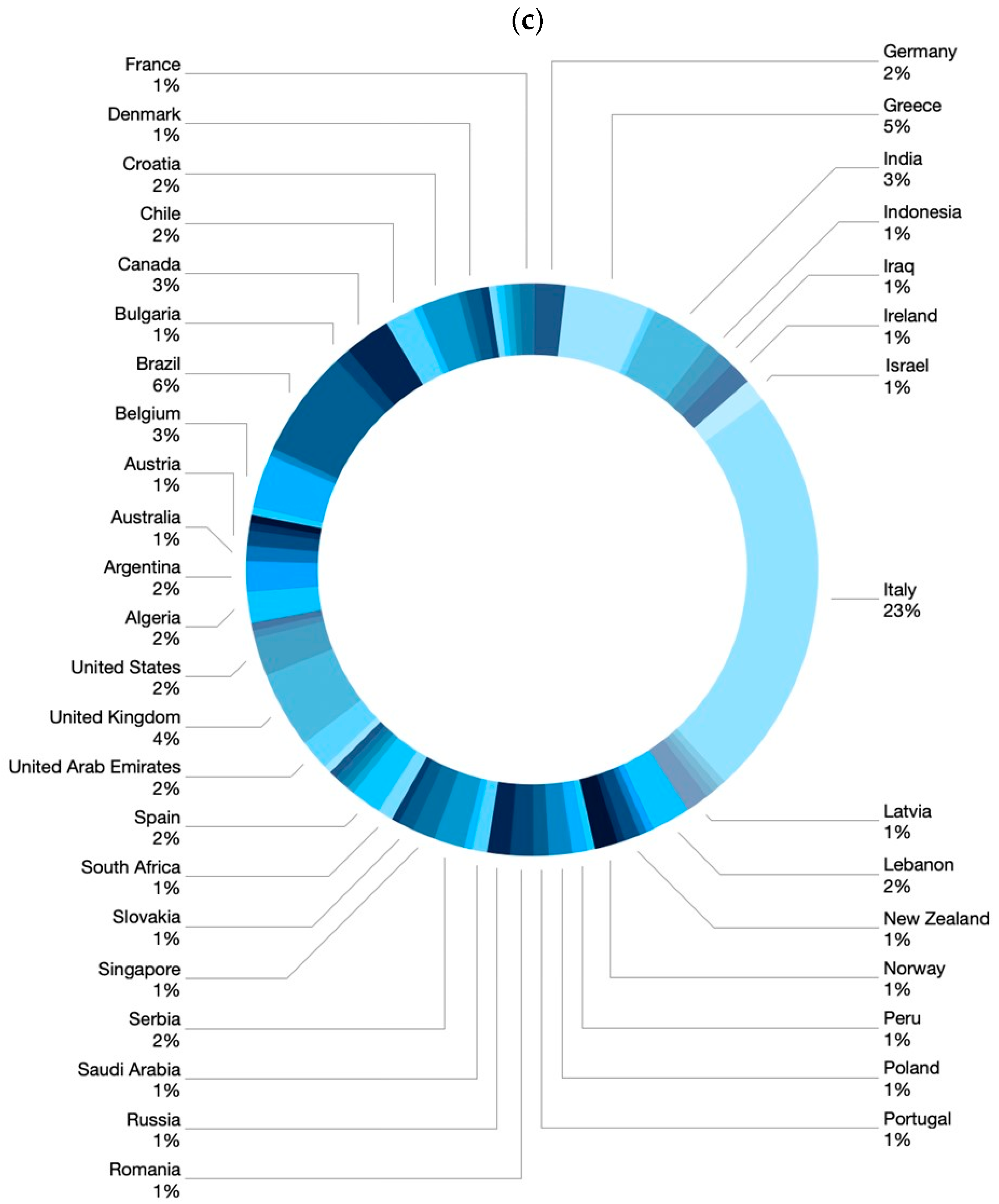

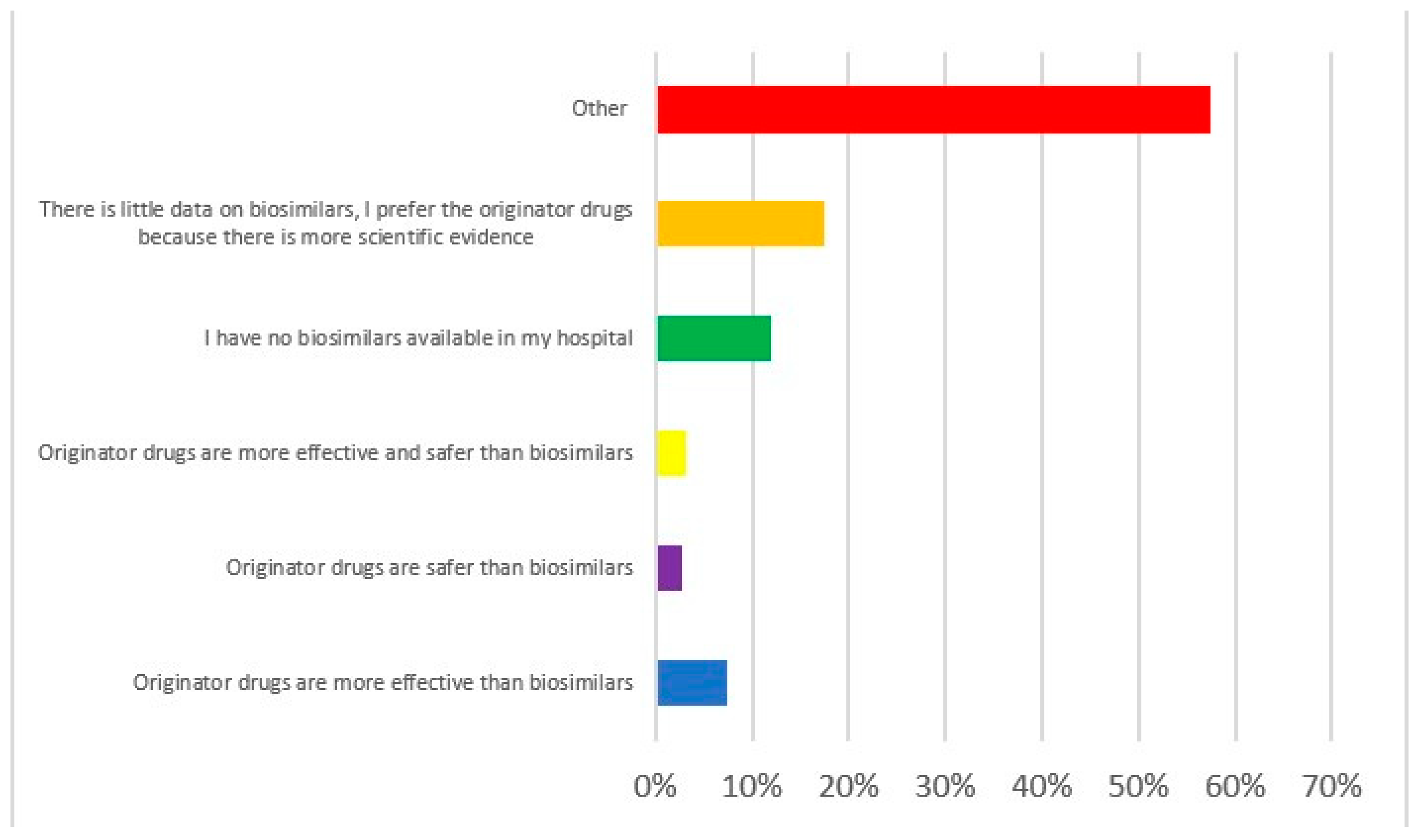

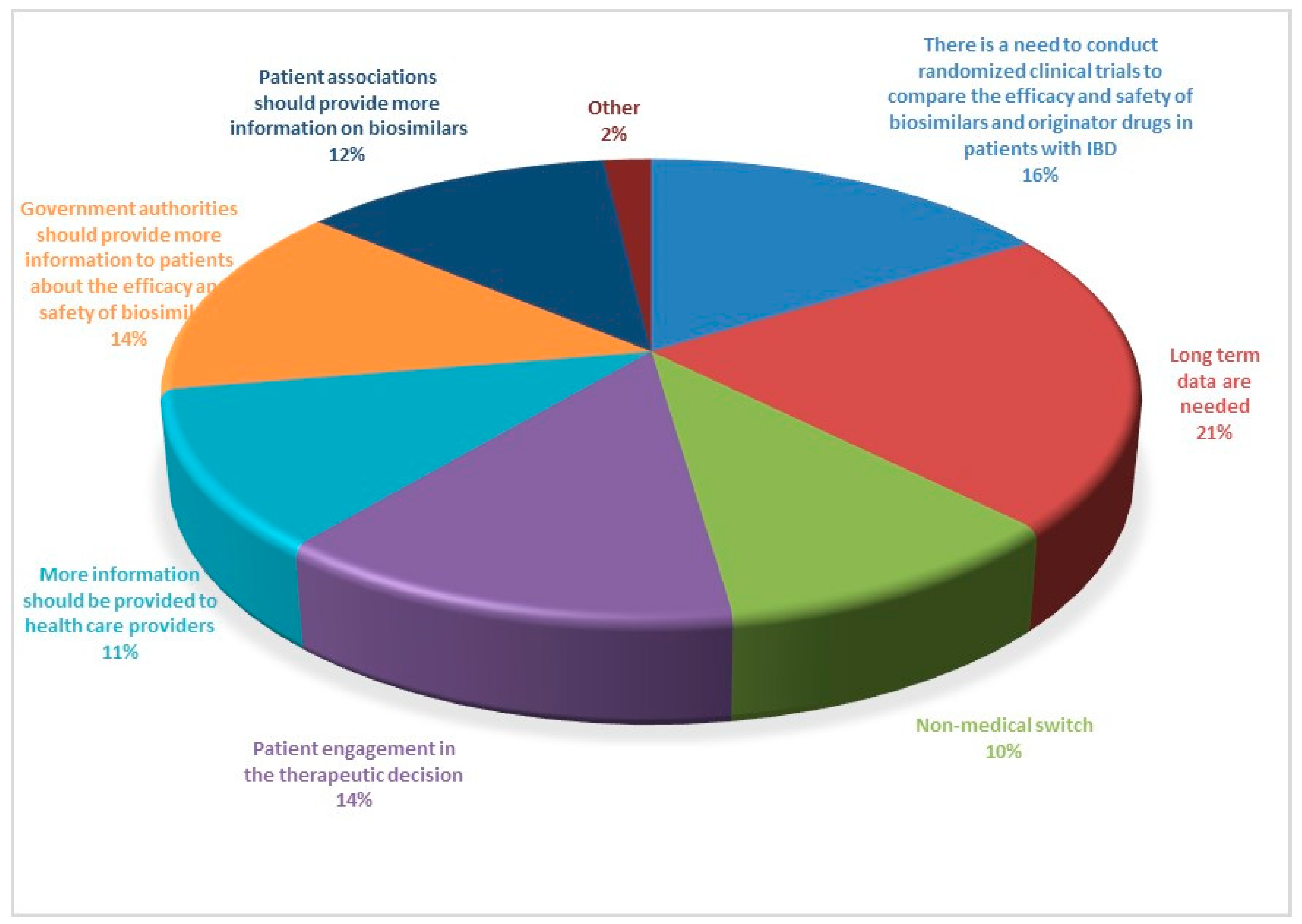

Part 1 Demographics, specialty, and level of experience of participants Q1. Age in years Q2. Sex Q3. What country do you work in? Q4. What is your specialization? Q5. How many years of experience do you have in the field of IBD? Q6. How many IBD patients do you see per year? Part 2 Practices and attitudes toward the use of biosimilar in clinical practice Q7. In your opinion, which of the following statements is correct? Q8. How confident are you about the use of biosimilars using a scale from 0 (lowest value) to 10 (highest value)? Q9. How confident are your patients about the use of biosimilars using a scale from 0 (lowest value) to 10 (highest value)? Q10. Do you think the data on biosimilars extrapolated from other immune mediated inflammatory diseases are also valid in IBD? Q11. Do you think patients should be informed about what a biosimilar is before starting therapy? Q12. Who should provide information to patients about biosimilars? Q13. Before prescribing a biological drug, do you explain to patients what a biosimilar drug is and what the originator drug is? Q14. Do you provide patients with data comparing biosimilars and originator drugs? Q15. Do you provide written materials to patients informing them on the use of biosimilars? Q16. Have you ever prescribed biosimilars of infliximab? Q17. Have you ever prescribed biosimilars of adalimumab? Q18. Do you think biosimilars should only be prescribed to naïve patients? Q19. Have you ever switched a patient from the originator drug to the biosimilar? Q20. If you answered yes to question 19, why did you switch from the originator drug to the biosimilar? Q21. When do you switch from the originator to the biosimilar? Q22. Do you monitor drug trough levels and autoantibodies in patients switched to biosimilars? Q23. Do you have patients who have refused to start therapy with a biosimilar or switch to a biosimilar? Q24. If you have patients who refused to be treated with a biosimilar, what is the proportion of these patients? Q25. What is the main reason for patients’ refusal of the biosimilar? Q26. Despite the availability of biosimilars, do you prescribe originator drugs? Q27. If you prescribe originator drugs despite the availability of the biosimilars, why do you prefer the originator drug? Q28. In a patient candidate for biologic therapy, have you ever started IBD therapy using biosimilars? Part 3. Interchangeability (reverse and multiple switch) Q29. In a patient who started a biosimilar as first drug, have you ever switched to the originator drug? Q30. If you answered yes to question 29, why were the patients switched from the biosimilar to the originator drug (multiple answers are possible)? Q31. If you answered yes to question 29, did patients switched from the biosimilar to the originator drug achieve/maintain disease remission? Q32. Have you ever switched from one biosimilar to another biosimilar of the same drug (multiple switch)? Q33. If you have multiple switched patients, why were the patients switched from one biosimilar to another (multiple answers are possible)? Q34. Did multiple switched patients achieve/maintain disease remission? Q35. In a patient treated with the originator drug and then switched to the biosimilar, have you ever prescribed the reverse switch to the originator drug? Q36. If you have patients undergoing reverse switch, what was the reason for reverse switch (multiple answers are possible)? Q37. Did reverse switched patients achieve/maintain disease remission? Part 4. Nocebo effect and non-medical switch Q38. Do you know what the nocebo effect is? Q39. Have your patients ever experienced the nocebo effect? Q40. If your patients experienced the nocebo effect, what is the rate of nocebo effect among your patients? Q41. Do you have patients who underwent a non-medical switch? Q42. Did non-medical switched patients achieve/maintain disease remission? Part 5. Current and future perspectives Q43. Does the presence of biosimilars have an impact on your therapeutic choices? Q44. In the near future, will you be prescribing biosimilars of vedolizumab, ustekinumab, and tofacitinib? Q45. Do you think the availability of the biosimilars of vedolizumab, ustekinumab, and tofacitinib will change the treatment algorithm of IBD patients? Q46. How would you implement the use of biosimilars in clinical practice (multiple answers are possible)? |

| Statements | Agreement >75% (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Biosimilars are as effective and safe as the originator drugs. | 100% |

| 2 | Biosimilars can be used both in biologic-naïve patients and in patients already treated with the originator drugs. | 100% |

| 3 | The main reason for switching from an originator drug to a biosimilar is its lower cost. | 100% |

| 4 | Switch from an originator drug to a biosimilar can be performed at any time. | 82% |

| 5 | The switch from an originator drug to a biosimilar is effective and safe. | 100% |

| 6 | Multiple switches from one biosimilar to another are feasible in case of drug unavailability. | 100% |

| 7 | We do not recommend multiple switches in case of loss of response to a biosimilar. | 100%* |

| 8 | There is no need to modify the regular practice in monitoring drug trough levels and antibodies in patients switched from the originator drug to the biosimilar. | 90%* |

| 9 | The non-medical switch is a way to reduce costs associated with advanced therapies and increase accessibility. | 100% |

| 10 | In the near future, non-anti-TNF biosimilar drugs are expected to alter the therapeutic algorithm in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. | 100% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).