1. Introduction

Interventional radiology (IR) has rapidly developed these recent years and, among the IR procedures, embolization is more frequently used and now part of routine care in various indications, including treatment of vascular anomalies. These interventions are performed using different embolization agents, as single use or in combination with other agents: coils, resorbable embolization agents (gelatin), liquid agents (cyanoacrylates or EVOH copolymers), plugs or microparticles. Endovascular embolization using metallic coils has been first reported in the treatment of vascular malformations such as cranial [

1,

2] or extra-cranial aneurysms [

3]. It is now recognized as an effective minimally invasive and safe treatment.

A wide variety of coils are available for embolization of vascular lesions, of different lengths, diameters, shapes, stiffnesses and types: fibrous or hydrogel-coated coils, with different types of detachment: controlled mechanical detachment coils and pushable coils. They each have advantages and disadvantages, but have been shown to be equally effective in terms of vascular occlusion [

4,

5,

6]. Coils can be thick and highly occlusive but rigid, requiring a large diameter microcatheter for placement, or thin and flexible, sometimes requiring multiple coils to achieve a dense packing, with greater risk of compaction and repermeabilisation of the aneurysm [

7,

8]. Hydrogel-coated coils have been developed to be more occlusive. Studies have shown them to be safe to use [

9] and more effective in occluding than conventional/naked coils [

10,

11]. Some coils can be released very simply by pushing them out of the catheter, but to ensure greater precision in the procedure, controlled release systems have been developed [

12]. Among these, mechanical release coils are hooked to the tip of the pusher, requiring a microcatheter large enough to contain the delivery system. Other controlled release systems based on an electrical process allow the use of smaller microcatheters [

1]. Even with the same structural composition, each type of coil is unique in terms of mechanical properties, and they show different degrees of flexibility/stiffness, specific deployment configurations, and variations in packing density. It is therefore important to evaluate new coils in terms of safety and efficacy in the embolization treatment of vascular anomalies

The Prestige coils (Balt, Montmorency, France) have recently been developed as platinum-based radiopaque coils, with an electrical detachment system that allows the utilization of large volume coils through a very small microcatheter. These coils were initially used for the treatment of intracranial aneurysms and were later used for the embolization of various peripheral vascular lesions. The main objectives of this multicentre retrospective study are to evaluate the efficacy and safety of Prestige coils and other materials used in peripheral vessel embolization, and to describe the indications and characteristics of the use of these Prestige coils, as well as to record the data related to the use of these coils.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Study design and patients

The study retrospectively analyzed data of 220 patients prospectively collected during standard care. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. It was performed according to the MR004 methodology and approved by the cell Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Patients included in the study were patients 18 years or older presenting vascular lesions outside neuroradiology, with indication for vessel occlusion using arterial or venous coils, scheduled or emergency. Patients were excluded if they had previous implantation of a Prestige coil in the same area, or if they participated in another study or currently in exclusion period of a previous study.

Patients were divided into two series, the Prestige series (series 1), with patients who underwent embolization with the use of Prestige coils, alone or in combination with other embolization materials (other coils or other materials); the Control series (series 2) included all other patients who underwent embolization without the use of a Prestige coil, whatever other embolization materials used. All data are available under convenient request.

Given the exploratory nature of this study, a formal calculation of the required sample size was not performed. However, to ensure an adequate sample size for studying the primary objective, it was determined that the inclusion of 100 patients per series would be appropriate. To account for potential loss to follow-up at the 1-month mark, an additional 10% of patients were included in each series. Patients were prospectively and consecutively enrolled until the predetermined target number of inclusions was reached in each series.

2.2. Study objectives

The primary objective was to evaluate the efficacy, i.e., success rate of embolization performed with the Prestige coils used alone or in combination with other embolization materials, compared with that of embolization performed with other embolization materials. The success rate at one month was also evaluated in the two series, as well as the technical success of the embolization procedure. Other objectives were to assess the safety of the embolization materials in the two series, and describe in the Prestige series, the indications, patients’ and technical characteristics. The risk of the procedure evaluated prior to the embolization, and the radiologist’s confidence in the procedure were also reported.

2.3. Embolization agents and procedure

The Prestige coils are platinum-tungsten coils with a steel hypotube, with a controlled detachment system, indicated for peripheral vascular embolization. The Prestige coils could be used alone or in combination with other embolization agents. Other embolization agents included other coils, liquid agent, spongel, microparticles or plugs.

The embolization procedure was performed by an interventional radiologist. The choice of device (prestige coil, other coil, other embolization material) was left to the discretion of the operator according to their usual practice. The approach was femoral, humeral or radial. Selective catheterization with the carrier catheter was performed, followed by microcatheterization of the target vessel. The correct positioning of the microcatheter was checked by injection of contrast medium before the embolization material was placed. A final control of the good occlusion of the vascular anomaly was systematically performed.

2.4. Follow-up

Follow-up were performed at 1 month, with a follow-up visit or by telephone according to the center’s standard practice. Clinical success, the patient’s general condition and possible adverse events were collected during each follow-up.

2.5. Study endpoints

The primary efficacy endpoint was successful embolization, defined as complete occlusion of the target vessel(s) with no residual filling of the embolized lesion(s), measured by angiography immediately after the procedure. The clinical success, evaluated at 1 month, was defined as the absence of (1) clinical worsening, (2) reintervention (surgery, second embolization) for the embolized target lesion or (3) death due to haemorrhagic recurrence within the first month after the procedure. The patient’s general condition (improvement, return to baseline state, stationary state, worsening) was assessed during the patient follow-up. The technical success was defined as the correct coil or plugs deployment in cases coils were used (Prestige or other coils and plugs), or as good ballistics of the embolization material (absence of uncontrolled reflux) in case liquid agents, spongel or microparticles were used. The technical risk of embolization was assessed before the start of the procedure by the radiologist, using a 4-point Likert scale “I consider the risk of the embolization procedure to be: 1: low, 2: medium; 3: high and 4: very high”. The technical characteristics of the Prestige coils, flexibility, pushability and packing density, were evaluated using 4-point Likert scales. The radiologist’s confidence in the procedure was assessed immediately after the procedure using a 4-point Likert scale; from 1: very low confidence to 4: very confident.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were descriptive, performed using biostattgv.com. Quantitative variables are presented with medians and 1st and 3rd quartiles (IQR), and categorical variables with numbers of patients and percentages.

3. Results

3.1. Patients

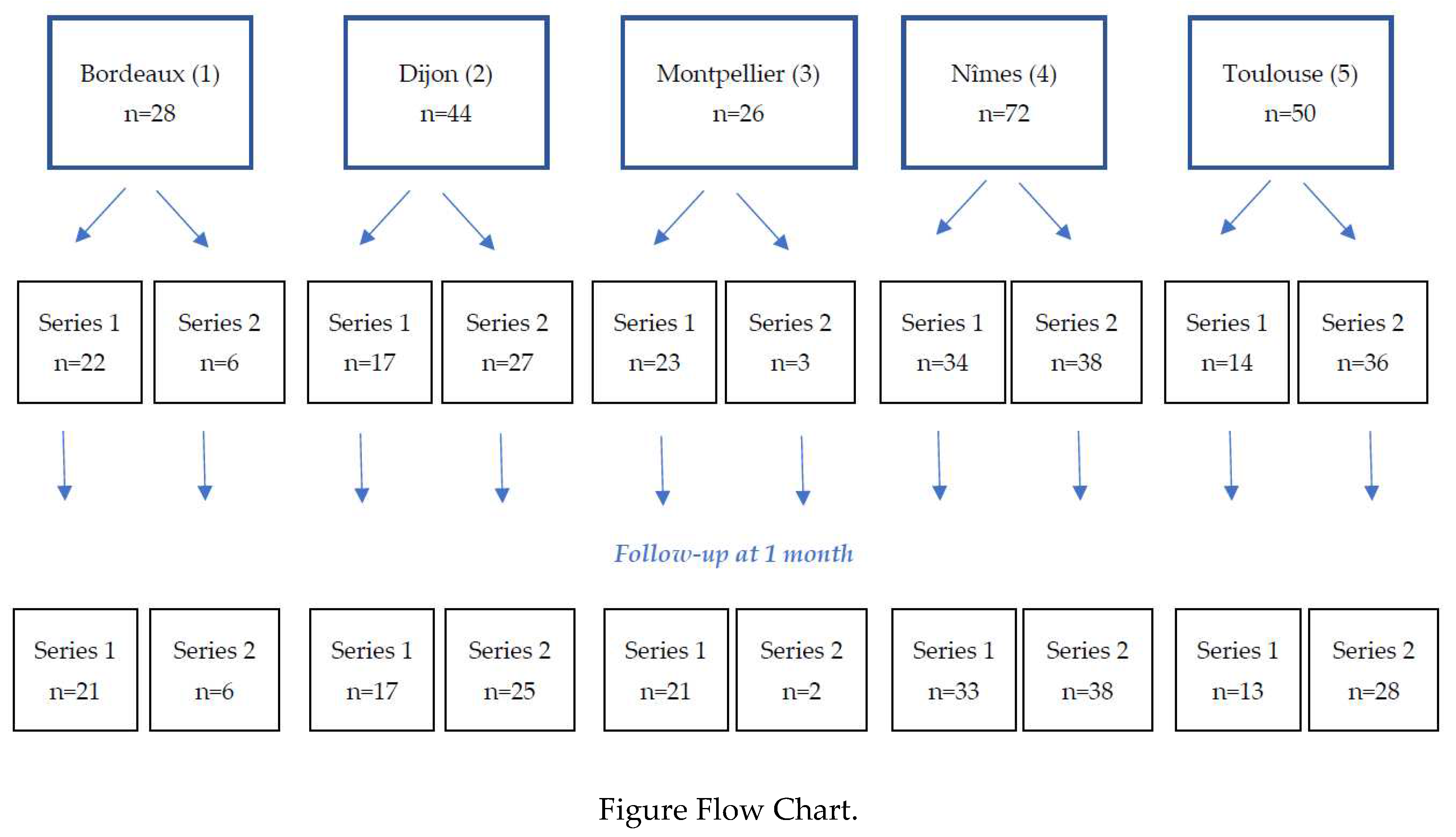

A total of 220 patients were included in the study in 5 participating centres, 110 in each series (figure flow chart). 204 patients completed their one-month follow-up.

Patients were 149 men (67.7%) and 71 women (32.3%), of median age 62.5 years [IQR: 35.8-73], similar in the two series (

Table 1). Patients were mostly of performance status 0 (n = 115, 52.8%) or 1 (n = 62, 28.4%). Patients in the Prestige series reported more comorbidities (diabetes, arterial hypertension and cirrhosis, p = 0.011) and previous anti-coagulant and anti-platelets treatments (p = 0.006) than patients in the control series.

3.2. Embolization data

Before the embolization procedure, the interventional radiologist was asked to rate the estimated risk of the procedure as poor, medium, high or very high. The procedure was rated as at low risk in 35.5% of cases, and at high risk in 23.6% (

Table 2).

Most embolizations (165, 75%) were performed on arterial anomalies, and 52 (23.6%) on venous anomalies. The median size of the anomaly was 6 mm [IQR: 4-12], and the median size of the occluded vessel was 5 mm [IQR: 3-6], higher in the control than in the Prestige series (

Table 2).

Prestige coils were used in 110 patients (series 1, 50%). They were used alone in 68/110 patients (61.8%) and in combination with other embolization agents in 42 (38.2%) of cases. Others embolization agents used in Series 1 were coils other than Prestige coils in 16 patients (14.5%), liquid agents in 24 patients (21.8%), spongel in 6 patients (5.5%), microparticles in 3 patients (2.7%) and plugs in 3 patients (2.7%) (

Table 3).

In Series 2, 49 patients (44.5%) were embolized with coils, 50 patients (45.5) with liquid agents, 16 (14.5%) with spongel, 7 (6.4%) with microparticles and 16 (14.5%) with plugs.

Among patients treated with coils, whatever the series, with Prestige or other coils, less than 10 coils were pushed in 134/159 patients (84.8%); the first coil pushed was of diameter < 6 mm for 91/159 patients (58.0%), and of length ≤ 15 cm for 89/159 patients (56.3%). A 2.7fr microcatheter was used in 123/210 patients (58.6%). Large microcatheters (2.7fr) were less frequently used in the Prestige series (n = 43/107, 40.2%) as compared to the control series (n = 80/203, 77.7%, p<0.001). The scopy time was 25 minutes [IQR: 16-39] in the Prestige series, significantly longer than in the control series (17.5 minutes [IQR: 10-30], p = 0.015).

3.3. Prestige coils characteristics

Data on the use of Prestige coils are presented in

Table 4. Mostly, Prestige coils were considered flexible or very flexible for all procedures, very easy or easy to push for 98.2% of procedures, and the packing density obtained was very dense or quite dense in more than 80% of procedures.

3.4. Immediate efficacy

Immediate clinical efficacy was evaluated at the end of the procedure. The complete occlusion of the targeted vessel, the primary endpoint of the study, was reported in 96.4% (N = 106/110) in the Prestige series and in 99.7% (N = 109/110) in Series 2, which was not significantly different in the two series (

Table 5). In the Prestige group, the coils were correctly positioned in all 110 patients.

3.5. 1-month efficacy

Short-term follow-up was collected for patients from the two series (

Table 6). Most patients had a better general state than before the intervention, 79% in the Prestige group and 74.7% in the control group. Among all patients, 10 patient (5.4%) died before the 1-month follow-up.

The median delay for the one month-follow-up (data available for 162/220 patients) was of 34 days [IQR: 30-45]. Among them, 48/162 follow-up were performed within the first month (< 30 days), and 111/162 within 40 days.

3.6. Safety

Four (4) non-serious adverse events without clinical consequences were declared in 4 patients (1.8%, N = 4/220) including: 1 vomiting and 1 back pain not related to the device in the Prestige group (Series 1); and 1 migration of material during embolization of complex vascular malformations which was related to the device, 1 hematoma at the punction site which were not related to the device in Series 2 [

13].

Three (3) device deficiencies/technical complications without clinical consequences occurred in 3 patients (1.4%, N = 3/220), all occurred in Series 1, (2.7%, N = 3/110). Two corresponded to coils that were difficult to push, which may be explained by a handling error resulting in a failure to detachment (1 patient) or an early detachment of the coil inside the microcatheter (1 patient).

Ten (10) deaths were reported at the 1-month follow up, 5 occurred in Prestige group (5.7%, N = 6/105) and 5 in the other group (5.1%, N = 5/99), p = 0.92. They all concerned patients embolised for arterial bleeding with a good outcome of the embolization at the end of the procedure.

4. Discussion

This study was the first multicentric study conducted in more than 200 patients to assess safety and efficacy of the Prestige coils compared to other embolization materials used in clinical practice. This study gives an overview of embolization of vascular anomalies in clinical routine in expert centres in France. This study shows real-life clinical practice of embolization with or without Prestige coils in 5 French centers with safety and immediate efficacy data, and the 1-month follow-up after embolization.

Our results showed in 220 patients that the Prestige coils are safe and efficient used in the context of embolization of peripheral vascular anomalies. Efficacy of the embolization procedure, i.e., complete occlusion of the target vessel, was similar in the two series (96.4% in the Prestige series, and 99.1% in the control Series), and the Prestige coils were reported as correctly positioned (technical success) in all cases (110/110 patients). Our results show that the Prestige coils, alone or in combination with other embolization agents (other coils, liquid agents, plugs…), are efficient when used for embolization of peripheral vascular anomalies, in various indications and context (scheduled or emergency), in various patients in an everyday life practice.

Very few studies have yet been published on the use of Prestige coils. Our results however are concordant with a previously published study [

13]. The coils were shown to be efficient in hemorrhoid embolization requiring soft microcoils and small catheters to obtain occlusion of small arteries [

13]. In this study, technical success was obtained in 100% (21/21) of the cases. Three (14.2%) patients underwent a second embolization due to rebleeding. One patient (4.7%) underwent surgery. No major complications were observed. Three patients had minor complications (one case of radial hematoma and two cases of minor tenesmus). We also report a very good safety. Among the 110 patients in the Prestige series, 5 deaths and 2 non-serious AE were reported, not related to the device used. The deaths concerned severe patients either with significant comorbidities or in haemorrhagic shock, treated for arterial anomalies. These deaths were not related to the device or the embolization procedure. It is difficult to compare with the literature because it is a real-life study, without selection of patients, including patients taken in emergency for multivisceral distress. There were 2 device deficiencies (detachment problems) and one technical complication (movement of the coil) which had no clinical consequence. This may be due to the fact that these coils were new to the interventional radiologists participating in the study. It is likely a learning curve is required to get used to the detachment of these new coils. However, operators were more often very confident with prestige coils compared to other embolic materials (50.0% vs. 35.5%, p = 0.04) which shows that once you are used to this new material you are comfortable with it.

The Prestige coils seem more adequate for small vessels and allow the use of small micro-catheters, potentially due to the miniaturized electric detachment system. This may be of use with the generalization of the embolization technique in other and newly-spreading indications such as prostatic artery [

14] or shoulder embolization [

15] in which use of microcatheter is essential in the small arteries implicated in these pathologies. Prestige coils are found flexible, but packing was not very tight in our study, as compared to a previous study by Hongo et al. which highlighted the packing density provided by the hydrocoils [

10]. However, the efficacy was similar to that of the control series, despite the fact that patients in the Prestige series had more frequently anticoagulant treatments.

Hongo et al. showed a lower number of coils and a shorter length with hydrogen-coated coils than with the non-hydrogen coated coils [

10]. In our study, there was no difference in the number of coils used in the two groups. The total length was not measured.

The fluoroscopy time was longer in the Prestige series than in the control series. This may be explained by the presence of smaller arteries, or more complex procedures requiring smaller microcatheter (p<0.001). However, there was no impact on the patients’ radiation dose thanks to the dose optimization work performed in interventional radiology suits, as shown in a previous published study on interventional radiology practices [

16].

This study has some limitations, among which the study design without randomization and the lack of independent core lab review. Also, packing density was not precisely calculated. The populations were heterogeneous but this study reflects real-life clinical practices of interventional radiology departments in five French centers.

5. Conclusions

This study reflects real-life clinical practices of interventional radiology departments in 5 French centers. We described the use of the Prestige coils used either alone or in combination with various other embolization materials (liquid agents, spongel, other coils, plugs …). Prestige coils were efficient both in combination with other materials and used alone, in various indications and artery types and sizes. They constitute another therapeutic option among all embolization agents already on the market. Their variety allow all the more a personalized medicine using one or more embolization agent depending on the indication and pathology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.F. and J.P.B.; methodology, J.F., J.P.B, H.R., R.L., C.M., H.V.K. ; validation, J.F., J.P.B, H.R., R.L., C.M., H.V.K.; formal analysis, J.F..; investigation, J.F., J.P.B, H.R., R.L., C.M., H.V.K.; resources, J.P.B ; data curation, J.F.; writing—original draft preparation, J.F.; writing—review and editing, J.F., J.P.B, H.R., R.L., C.M., H.V.K., O.C.,J.G., D.D., S.S.; and P.M.; visualization, J.F.; supervision, J.P.B.; project administration, J.F. and J.P.B.; funding acquisition, J.F. and J.P.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Balt Extrusion SAS.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. It was performed according to the MR004 methodology and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Nîmes University Hospital (IRB number 22-11-01).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available under convenient request.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Hélène De Forges, medical writer at the Nîmes University Hospital, France, for her help in writing and editing this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

JF was a member of the Prestige scientific committee and had a scientific expertise contract with Balt Extrusion SAS.

References

- Eskridge JM, Song JK. Endovascular embolization of 150 basilar tip aneurysms with Guglielmi detachable coils: results of the Food and Drug Administration multicenter clinical trial. J Neurosurg 1998;89:81–6. [CrossRef]

- Murphy KJ, Houdart E, Szopinski KT, Levrier O, Guimaraens L, Kühne D, et al. Mechanical detachable platinum coil: report of the European phase II clinical trial in 60 patients. Radiology 2001;219:541–4. [CrossRef]

- Klein GE, Szolar DH, Karaic R, Stein JK, Hausegger KA, Schreyer HH. Extracranial aneurysm and arteriovenous fistula: embolization with the Guglielmi detachable coil. Radiology 1996;201:489–94. [CrossRef]

- Perdikakis E, Fezoulidis I, Tzortzis V, Rountas C. Varicocele embolization: Anatomical variations of the left internal spermatic vein and endovascular treatment with different types of coils. Diagn Interv Imaging 2018;99:599–607. [CrossRef]

- Molyneux AJ, Clarke A, Sneade M, Mehta Z, Coley S, Roy D, et al. Cerecyte coil trial: angiographic outcomes of a prospective randomized trial comparing endovascular coiling of cerebral aneurysms with either cerecyte or bare platinum coils. Stroke 2012;43:2544–50. [CrossRef]

- McDougall CG, Johnston SC, Gholkar A, Barnwell SL, Vazquez Suarez JC, Massó Romero J, et al. Bioactive versus bare platinum coils in the treatment of intracranial aneurysms: the MAPS (Matrix and Platinum Science) trial. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014;35:935–42. [CrossRef]

- Nemoto S, Iwama J, Mayanagi Y, Kirino T. Coil Embolization of Cerebral Aneurysms. Experience with IDC and GDC. Interv Neuroradiol 1998;4 Suppl 1:159–64. [CrossRef]

- Slob MJ, van Rooij WJ, Sluzewski M. Coil thickness and packing of cerebral aneurysms: a comparative study of two types of coils. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005;26:901–3.

- White PM, Lewis SC, Nahser H, Sellar RJ, Goddard T, Gholkar A, et al. HydroCoil Endovascular Aneurysm Occlusion and Packing Study (HELPS trial): procedural safety and operator-assessed efficacy results. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008;29:217–23. [CrossRef]

- Hongo N, Kiyosue H, Ota S, Nitta N, Koganemaru M, Inoue M, et al. Vessel Occlusion using Hydrogel-Coated versus Nonhydrogel Embolization Coils in Peripheral Arterial Applications: A Prospective, Multicenter, Randomized Trial. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2021;32:602-609.e1. [CrossRef]

- Taschner CA, Chapot R, Costalat V, Machi P, Courthéoux P, Barreau X, et al. GREAT-a randomized controlled trial comparing HydroSoft/HydroFrame and bare platinum coils for endovascular aneurysm treatment: procedural safety and core-lab-assessedangiographic results. Neuroradiology 2016;58:777–86. [CrossRef]

- Guglielmi G, Viñuela F, Dion J, Duckwiler G. Electrothrombosis of saccular aneurysms via endovascular approach. Part 2: Preliminary clinical experience. J Neurosurg 1991;75:8–14. [CrossRef]

- Khalilzadeh O, Baerlocher MO, Shyn PB, Connolly BL, Devane AM, Morris CS, et al. Proposal of a New Adverse Event Classification by the Society of Interventional Radiology Standards of Practice Committee. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2017;28:1432-1437.e3. [CrossRef]

- De Gregorio MA, Bernal R, Ciampi-Dopazo JJ, Urbano J, Millera A, Guirola JA. Safety and Effectiveness of a New Electrical Detachable Microcoil for Embolization of Hemorrhoidal Disease, November 2020-December 2021: Results of a Prospective Study. J Clin Med 2022;11:3049. [CrossRef]

- Amouyal G, Tournier L, De Margerie-Mellon C, Pachev A, Assouline J, Bouda D, et al. Safety Profile of Ambulatory Prostatic Artery Embolization after a Significant Learning Curve: Update on Adverse Events. J Pers Med 2022;12:1261. [CrossRef]

- Gremen E, Frandon J, Lateur G, Finas M, Rodière M, Horteur C, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Embolization with Microspheres in Chronic Refractory Inflammatory Shoulder Pain: A Pilot Monocentric Study on 15 Patients. Biomedicines 2022;10:744. [CrossRef]

- Greffier J, Dabli D, Kammoun T, Goupil J, Berny L, Touimi Benjelloun G, et al. Retrospective Analysis of Doses Delivered during Embolization Procedures over the Last 10 Years. J Pers Med 2022;12:1701. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics at baseline.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics at baseline.

| n (%) |

Series 1 (n = 110) |

Series 2 (n = 110) |

Total (n = 220) |

p-values |

| Age* |

64.5 [38.3-73.0] |

59.0 [34.0-71.8] |

62.5 [35.8-73] |

0.13 |

| Gender |

|

|

|

|

| Men |

71 (64.5) |

78 (70.9) |

149 (67.7) |

0.31 |

| Women |

39 (35.5) |

32 (29.1) |

71 (32.3) |

|

| Comorbidities |

|

|

|

0.011 |

| Diabetes |

13 (11.7) |

7 (6.4) |

20 (9.1) |

|

| Arterial hypertension |

47 (42.3) |

31 (28.2) |

78 (35.5) |

|

| Cirrhosis |

4 (3.6) |

2 (1.8) |

6 (2.7) |

|

| Performance status |

|

|

|

0.14 |

| 0 |

50 (45.9) |

65 (59.6) |

115 (52.8) |

|

| 1 |

37 (33.9) |

25 (22.9) |

62 (28.4) |

|

| 2 |

14 (12.8) |

15 (13.8) |

29 (13.3) |

|

| 3 |

3 (2.8) |

3 (2.8) |

6 (2.8) |

|

| 4 |

5 (4.6) |

1 (0.9) |

6 (2.8) |

|

| Missing |

1 |

1 |

2 |

|

| Previous treatments |

|

|

|

0.006 |

| Anti-coagulant |

24 (21.6) |

11 (10.0) |

35 (15.9) |

|

| Anti-platelets |

25 (22.5) |

16 (14.5) |

41 (18.6) |

|

Table 2.

Vascular anomaly data.

Table 2.

Vascular anomaly data.

| n (%) |

Series 1 (n = 110) |

Series 2 (n = 110) |

Total (n = 220) |

p-values |

| Risk of the procedure |

|

|

|

0.16 |

| Low |

42 (38.2) |

36 (32.7) |

78 (35.5) |

|

| Medium |

48 (43.6) |

42 (38.2) |

90 (40.9) |

|

| High |

20 (18.2) |

32 (29.1) |

52 (23.6) |

|

| Vascular anomaly |

|

|

|

0.08 |

| Arterial |

89 (80.9) |

78 (70.0) |

167 (75.9) |

|

| Venous (variquous) |

20 (18.2) |

32 (29.1) |

52 (23.6) |

|

| Others |

1 (0.9) |

0 |

1 (0.05) |

|

| Arterial anomalies |

|

|

|

0.21 |

| Aneurism |

21 (23.6) |

10 (14.3) |

31 (21.1) |

|

| Faux aneurism |

18 (20.2) |

19 (27.1) |

37 (25.2) |

|

| Bleeding |

29 (32.6) |

36 (51.4) |

65 (44.2) |

|

| Arteriovenous fistula |

4 (4.5) |

3 (4.3) |

7 (4.8) |

|

| Malformation |

5 (5.6) |

2 (2.9) |

7 (4.8) |

|

| Missing |

12 |

8 |

19 |

|

| Embolized artery |

|

|

|

|

| Hepatic artery |

3 (3.5) |

|

|

|

| Splenic artery |

13 (15.1) |

|

|

|

| Superior mesenteric artery |

4 (4.7) |

|

|

|

| Inferior mesenteric artery |

4 (4.7) |

NA |

NA |

|

| Left gastric artery |

1 (1.2) |

|

|

|

| Gastroduodenal artery |

5 (5.8) |

|

|

|

| Hypogastric artery |

13 (15.1) |

|

|

|

| Renal artery |

13 (15.1) |

|

|

|

| Others |

30 (34.9) |

|

|

|

| Missing |

3 |

|

|

|

| Embolized vein |

|

|

|

|

| Spermatic vein |

16 (80.0) |

|

|

|

| Ovarian vein |

1 (5.0) |

NA |

NA |

|

| Others |

3 (15.0) |

|

|

|

Size of the vascular anomaly*

Missing

|

6 [4-14]

0

|

6 [5-10]

1

|

6 [4-12]

1

|

0.056

|

| Size of the occluded vessel* |

4 [3-6] |

5 [3-6] |

5 [3-6] |

0.038 |

Table 3.

Embolization technical data.

Table 3.

Embolization technical data.

| N (%) |

Series 1 (n = 110) |

Series 2 (n = 110) |

Total (n = 220) |

p-values |

| Embolization agent used |

|

|

|

|

| Prestige coils |

110 (100) |

0 |

110 (50) |

|

| Other coils |

16 (14.5) |

49 (44.5) |

65 (29.5) |

|

| Liquid agent |

24 (21.8) |

50 (45.5) |

74 (33.6) |

|

| Spongel |

6 (5.5) |

16 (14.5) |

22 (10.0) |

|

| Microparticles |

3 (2.7) |

7 (6.4) |

10 (4.5) |

|

| Plug |

3 (2.7) |

16 (14.5) |

19 (8.6) |

|

|

Number of coils used**

|

|

|

|

0.11 |

| 0-9 |

89 (80.9) |

45 (93.8) |

134 (84.8) |

|

| 10-29 |

17 (15.5) |

3 (6.3) |

20 (12.7) |

|

| 30-50 |

4 (3.6) |

0 |

4 (2.5) |

|

| Missing |

0 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Length of the first coil pushed**

|

|

|

|

0.4 |

| ≤ 15 cm |

63 (57.3) |

26 (54.2) |

89 (56.3) |

|

| 15-30 cm |

27 (24.5) |

9 (18.8) |

36 (22.8) |

|

| > 30 cm |

20 (18.2) |

13 (27.1) |

33 (20.9) |

|

| Missing |

0 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Diameter of the first coil pushed**

|

|

|

|

0.31 |

| < 6 mm |

65 (59.1) |

26 (55.3) |

91 (58.0) |

|

| 6-10 mm |

27 (24.5) |

17 (36.2) |

44 (28.0) |

|

| 11-20 mm |

13 (11.8) |

2 (4.3) |

15 (9.6) |

|

| ≥ 20 mm |

5 (4.5) |

2 (4.3) |

7 (4.5) |

|

| Missing |

0 |

2 |

2 |

|

| Microcatheter size |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| ≤ 2.0 fr |

12 (11.2) |

5 (4.9) |

17 (8.1) |

|

| 2.4 fr |

52 (48.6) |

18 (17.5) |

70 (33.3) |

|

| ≥ 2.7 fr |

43 (40.2) |

80 (77.7) |

123 (58.6) |

|

| Missing |

3 |

7 |

10 |

|

| Scopy time* |

25 [16-39] |

17.5 [10-30] |

22 [13-37] |

0.015 |

| Missing |

2 |

10 |

12 |

|

| Radiation dose* |

47060

[23637-115621] |

34385

[18077-98077] |

39470

[19550-107878] |

0.26 |

| Missing |

3 |

10 |

10 |

|

Table 4.

Characteristics of the Prestige coils.

Table 4.

Characteristics of the Prestige coils.

| n (%) |

Series 1 (n = 110) |

| Flexibility of the coil |

|

| Very flexible |

61 (55.5) |

| Flexible |

49 (44.5) |

| Rigid |

0 |

| Very rigid |

0 |

| Pushability |

|

| Very easy to push |

61 (55.5) |

| Easy to push |

47 (42.7) |

| Difficult to push |

2 (1.8) |

| Very difficult to push |

0 |

| Packing density |

|

| Not dense at all |

2 (1.8) |

| A little dense |

17 (15.6) |

| Quite dense |

56 (51.4) |

| Very dense |

34 (31.2) |

| Missing |

1 |

Table 5.

Efficacy of the embolization procedure according to the embolization agent used, in the two series.

Table 5.

Efficacy of the embolization procedure according to the embolization agent used, in the two series.

| n (%) |

Series 1 (n = 110) |

Series 2 (n = 110) |

Total (n = 220) |

p-values |

| Correct positioning of the coil/embolization agent |

|

|

|

|

| Prestige coil |

110 (100) |

NA |

|

|

| Other coils#* |

15 (13.6) |

46 (41.8) |

|

|

| Liquid agent* |

24 (21.8) |

49 (44.5) |

|

|

| Spongel* |

6 (5.5) |

15 (13.6) |

NA |

|

| Microparticles* |

2 (1.8) |

7 (6.4) |

|

|

| Plug* |

3 (2.7) |

15 (13.6) |

|

|

| Complete occlusion of the target vessel |

106 (96.4) |

109 (99.1) |

215 (97.7) |

0.17 |

| Confidence of the radiologist in his/her procedure |

|

|

|

0.04 |

| Not very confident |

1 (0.9) |

0 |

1 (0.5) |

|

| A bit confident |

1 (0.9) |

1 (0.9) |

2 (0.9) |

|

| Confident |

53 (48.2) |

70 (63.6) |

123 (55.9) |

|

| Very confident |

55 (50.0) |

39 (35.5) |

94 (42.7) |

|

Table 6.

One-month efficacy follow-up.

Table 6.

One-month efficacy follow-up.

| n (%) |

Series 1 (n = 105) |

Series 2 (n = 99) |

Total (n = 204) |

p-values |

| Lost to follow-up/Missing |

5 |

11 |

16 |

0.12 |

| Improvement |

83 (79.0) |

74 (74.7) |

157 (77.0) |

0.99 |

| Steady state |

1 (1.0) |

1 (1.0) |

2 (1.0) |

0.97 |

| Back to baseline state |

16 (15.2) |

18 (18.2) |

34 (16.7) |

0.57 |

Aggravation

Incl death |

6 (5.7)

5 (4.8) |

6 (6.1)

5 (5.1) |

12 (5.9)

10 (5.4) |

0.92 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).