1. Introduction

Urban Agriculture (UA) is the practice of agriculture within urban and peri-urban settings [

1] and, in Africa, it is an ancient practice. For instance, Juhé-Beaulaton’s [

2] historical investigations in Dahomey (Benin) demonstrated that plant cultivation in cities of the Gulf of Guinea dates to well before the arrival of European travelers. The author drew on these travelers’ accounts recording oral testimonies of the inhabitants of the towns studied.

According to Sibhatu and Qaim [

3], agriculture was a sector of activity, contributing to the daily subsistence of these people in Africa. It was part of most strata of society, even in urban areas. Secondly, literature relating to the colonial and post-colonial period of UA in Africa shows that this activity persisted in recent times, to “meet the consumption needs of bureaucrats, colonists and other elites.” [

4]. After the independence movements, with the intense rural exodus that followed, the former inhabitants of rural areas who found themselves in the towns without jobs, started practicing UA to it as an income-generating activity [

5].

Among the different functions the city has, it also requires finding the means to feed its inhabitant [

6]. Including other “vital” functions, energy and food security are two essential items and food insecurity has especially been confirmed during the Covid-19 pandemic [

7]. According to [

8,

9,

10], UA has, arguably, become a key contributor to ensure food security in cities. The demographic and spatial growth of cities and the need for energy especially in Global South cities is a matter for consideration. For Nagendra et al., this growth is the most spectacular there: “Ninety per cent of the projected world population growth of 2.5 billion over the next couple of decades will occur in the cities of Africa and Asia.” [

11].

In addition, public health has been a key issue in urban planning in Africa, especially since colonial times [

8,

9,

10,

12]. “Modern” public health and urban planning rose in 19th century Europe, a few decades before colonial occupations were consolidated by the Berlin Conference. Following the ravages of various infectious diseases, public authorities decided to redesign and invest in urban infrastructures considered essential to prevent deadly epidemics like cholera epidemic in England [

13]. In a similar context, it has been historically demonstrated that the organization of colonial cities in Africa was done according to health issues [

14]. What is more, today’s researchers are increasingly proving that the role of the of urban agriculture in addressing food security, employment, and sustainability in cities, including those in Africa [

15]. Moreover, have been published on the subject of practice of urban agriculture and its potential contributions to sustainable development in various regions in the world, Africa included [

16]. Discussions are also made on urbanization’s impact on ecosystems and the potential for urban agriculture to mitigate some of these effects [

17]. On the other hand, the focus is increasingly on the social, political, and environmental dimensions of urban agriculture, providing insights into its significance in Africa and on other continents [

18].

Despite their historical synergy, today the fields of urban planning and public health have been disconnected in Africa [

19]. In this regard, UA might be a fruitful platform to reconnect those disciplinary fields [

20]. This literature review paper systematically examines the literature on UA and health in Africa. Africa being known as continent with an unprecedent growing urban population [

11]. This phenomenon must avoid saturation [

21] and parallelly, planning UA which is already an ancient socio-cultural and economic practice of African communities could help in caring for this growing population.

Beyond the fact that urban agriculture as le community garden participation can positively influence fruit and vegetable consumption, thereby contributing to improved public health outcomes [

22], other studies have emphasized the need for collaboration between urban planners, architects, and community members to maximize these benefits [

22]. Some authors have also been discussing the integration of urban agriculture into urban design and planning, accentuating the potential for improved health outcomes through access to fresh produce and green spaces [

23]. Others examine the health effects of urban agriculture and highlight the role of urban planners and architects in creating supportive environments that encourage and facilitate such practices [

24].

In the same vein as above, this study aimed to explore architecture and urban planning researchers in UA in Africa, as well as its potential health impacts. This was motivated by the hypothesis that that urban planning researchers and practitioners have not substantially contributed to the scientific discussion on the subject, even though they could play an important role in reducing the health risks of UA, while increasing its benefits, through adequate spatial and regulatory frameworks. To test this hypothesis, three specific objectives were derived. The first was to assess the general evolution of the interest in the UA-urban health linkages in recent decades (2000-2020). The second was to assess the specific role of urban planners in the knowledge production on UA and health in Africa, by quantifying the number of works in this field, as compared to other fields. The third and last objective was to establish an overview of the positive and negative health impacts of UA in African cities.

3. Methodology and materials

3.1. Data collection

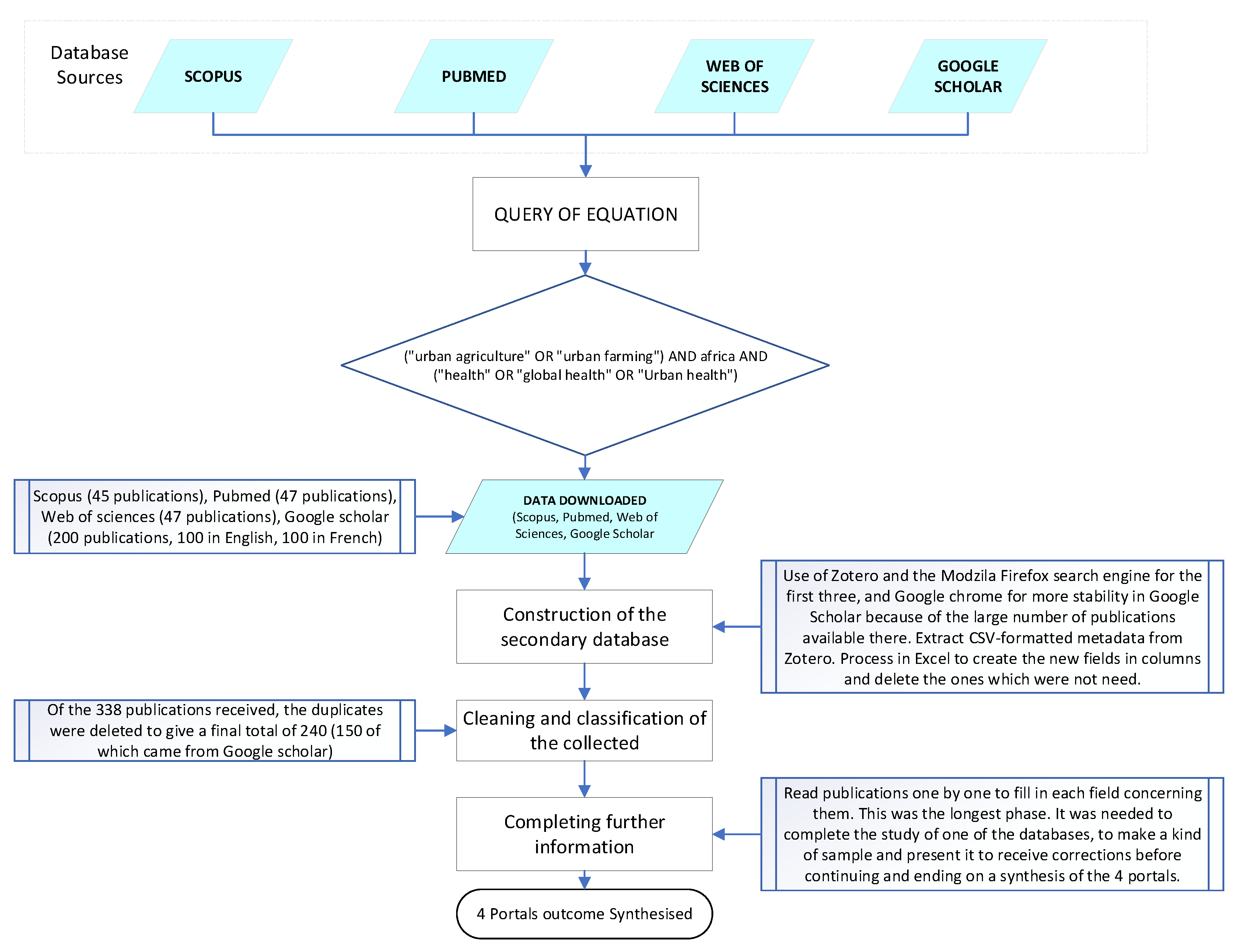

Figure 1 is a schematic representation of the steps taken to collect the data used in this study. Another criterion was the word “health” and the concepts “global health” and “urban health”. Finally, the labels “urban agriculture”, “urban farming”, “africa”, “health”, “global health”, and “urban health” were kept. The research query equation was defined after several trials to get as many accurate documents as possible, matching the keywords. The following query string was formed: (“urban agriculture” OR “urban farming”) AND africa AND (“health” OR “global health” OR “Urban health”)).

Experience has shown that the results obtained depending on the type of browser used are also characteristic of the data obtained, especially when it comes to Google Scholar. For example, the royalty-free literature collection software Zotero was used, along with the search engine Modzila firefox for the first three, and Google Chrome for greater stability in Google Scholar due to the large number of publications available.

For an in-depth analysis of the data, the metadata was extracted in CSV format from Zotero. They were then processed in Microsoft Excel to create the new fields in column form, and to delete the fields not required. Finally, the most tedious stage was the one where all the publications were read one by one to fill in each field.

3.2. Analysis step

Once the data was collected, cleaned, and arranged, we used Microsoft Excel 16 spreadsheets to produce graphs corresponding to the various areas of analysis. The latter were as follows:

- (1)

A typological analysis: since this research included both grey and scientific publications, we established a typological profile of these publications. The metadata in Zotero’s “Item Type” column shows whether the publication was a book, a thesis, a journal article, a conference paper, or a book section.

- (2)

The results obtained from this analysis informed the preferential types of publications by field.

- (3)

A numerical analysis: a systematic count was made of all publications from the year 2000 to 2020 to evaluate the chronological evolution. The goal is to determine if the subject has been of interest or not during the last 20 years.

- (4)

A departmental/institutional analysis: the analysis was made of the different disciplines from which the publications come. These affiliations can be found by going back to each online article, clicking on the first author of each publication, to see the institutions in which they worked while writing the paper. This analysis allowed us to define the fields which have been involved in researching the subject and in seeing whether urban planners made a significant contribution during the reference year.

- (5)

A thematic analysis: Under the overall umbrella of UA and health, more specific studies are being done. Thematic analysis was, therefore, the place to evaluate these different subjects. Based on the list of titles, abstracts and keywords, the dominant topics have been identified, which in turn have been classified under themes, by covering them with a group of globalizing terms. This phase of the analysis estimated the themes most dealt with to understand their importance in the field of research, and to evaluate whether the research orientation according to these themes is by reality.

- (6)

A chronological evolution of topics: in addition to defining the types of topics that have been dealt with between the years 2000 and 2020 under the broad theme of UA and health, a chronological schematization was conducted. The latter served to analyze the movement of these topics throughout the reference period.

- (7)

A geographical analysis of the study sites: this consisted in identifying the countries concerned by the research. Publication titles, keywords and abstracts were used to find the country or countries chosen as case studies. A table was then drawn up including these countries and the number of publications per country.

- (8)

A geographical analysis of the affiliation of first authors: the second geographical analysis is about the countries in which the first authors were based.

- (9)

A general health impact assessment: this consisted in determining whether the selected publications considered UA to be more of a risk than a health benefit, or both. This was defined based on the title, abstract and conclusion.

4. Results

By database, here is the number of publications that has been obtained:

Scopus (n = 45 publications), Pubmed (n = 47 publications), Web of Sciences (n = 47 publications), and Google Scholar.

4.1. Types of publications

The review of the types of publications around this general theme picked among academic peer-reviewed articles and gray literature showed a more significant number of journal articles (83%) followed by books (7%) and conference papers (6%). There was no book nor book section at all, in the Pubmed list.

4.2. Variation in the number of publications over the last 20 years

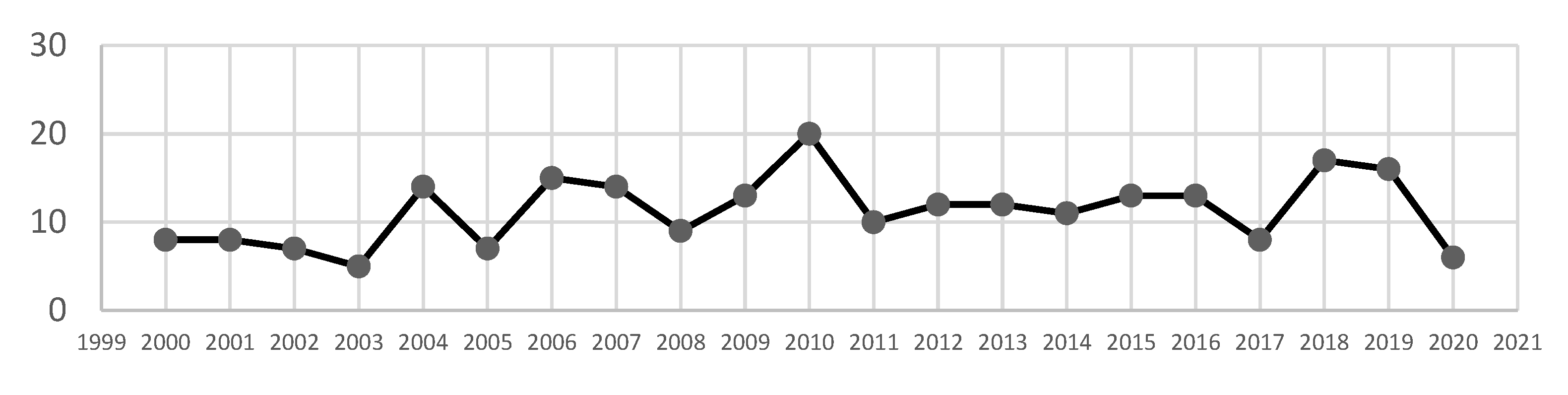

From the analysis, the number of publications over all 20 years (

Figure 2) reveals an average growth, peaking in the 2006-2010 quintile (precisely n = 24 publications in 2010). A drop of half value followed in 2011 and then in 2017, but since then, the subject seems to be growing in number, and the 2018-2019s have also seen growth (respectively n = 21, and n = 20 publications).

4.3. Main fields of affiliation of first authors in a logarithmic scale (only with Scopus, Web of Science and Pubmed data)

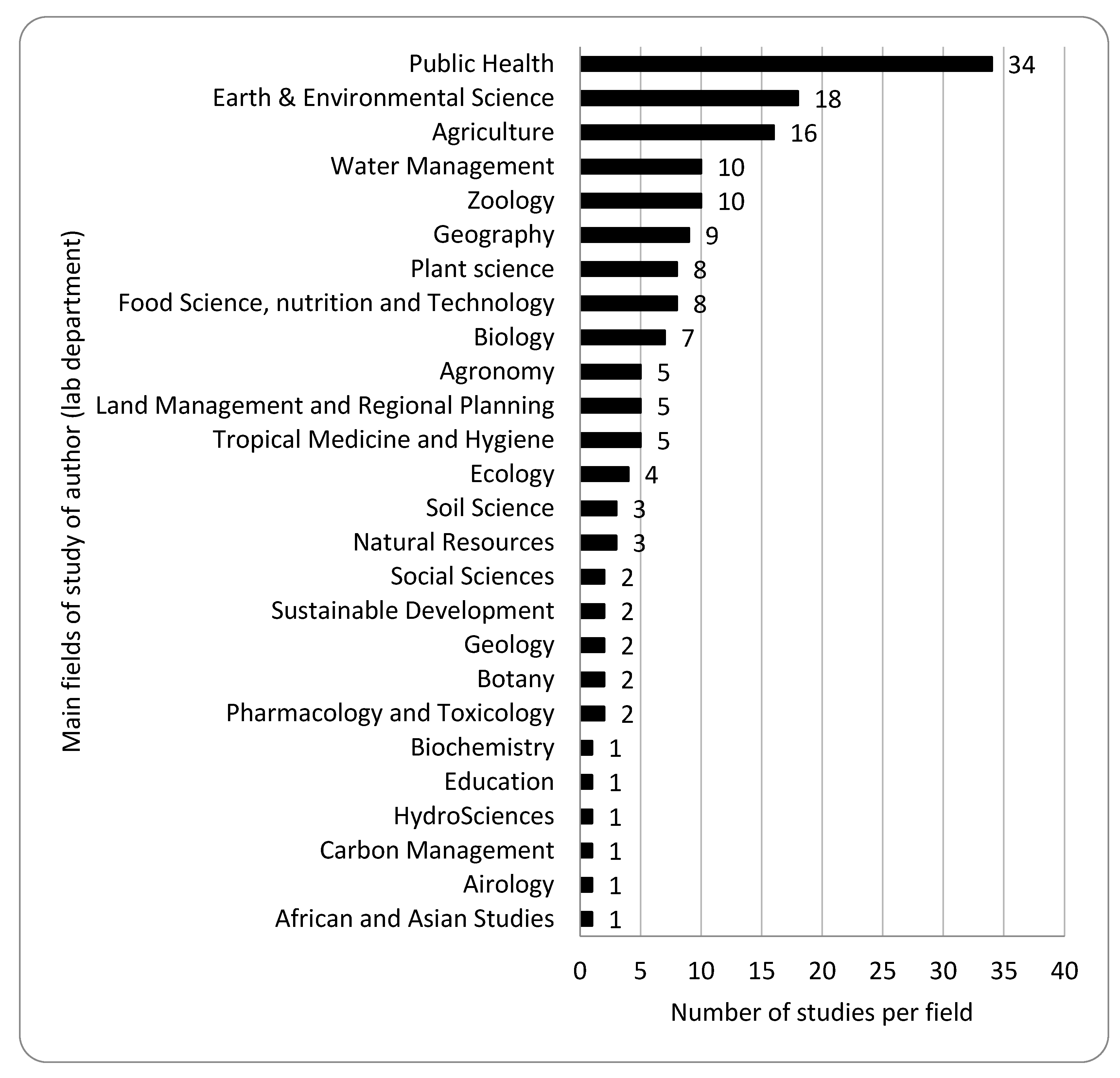

Looking at what types of fields or departments have already initiated research under the general theme (

Figure 3), the first is Public Health (n = 34 publications or 21%), Earth and Environmental Science (n = 18 publications or 11%) and Agriculture (n = 16 publications or 10%). Zoology comes following them, chased by Water Management.

4.4. Areas of resarch

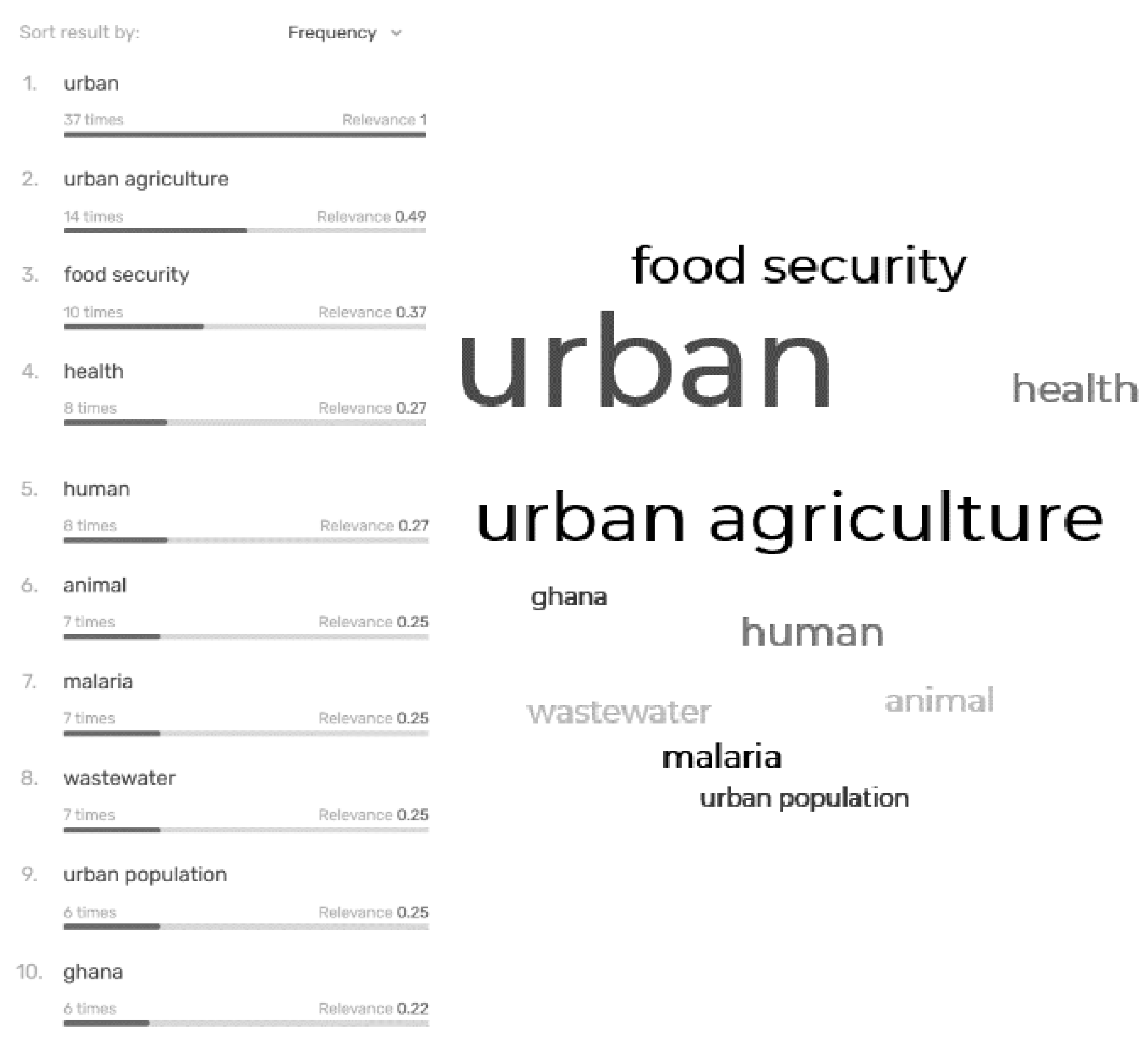

As far as the most encountered themes are concerned, they also follow the fields of study. The topics are Food Security (22%), Wastewater Irrigation Risks (12%), broad characteristics of UA as experienced in Africa (11%), Malaria Risks (8%) and health impacts of UA considered in general (7%). The Socio-economic status and benefits topic is less treated, as much as the land-use subject (5% each). At the end, an image is obtained with the words that appeared the most in the list appearing with a larger size, a more central position, and a greater writing thickness as well. In the following images from monkeylearn.com (

Figure 4), the words “Food security” and “Human”, “Malaria, and “Wastewater”are the most prominent, apart from “Urban” and “Urban agriculture”,, which are already keywords in the search equation. Monkeylearn online word cloud generator was selected for this paper due to its capability to highlight the ten most pertinent words based on frequency, thereby enhancing reader comprehension.

4.5. Chronological evolution of topics (only Scopus)

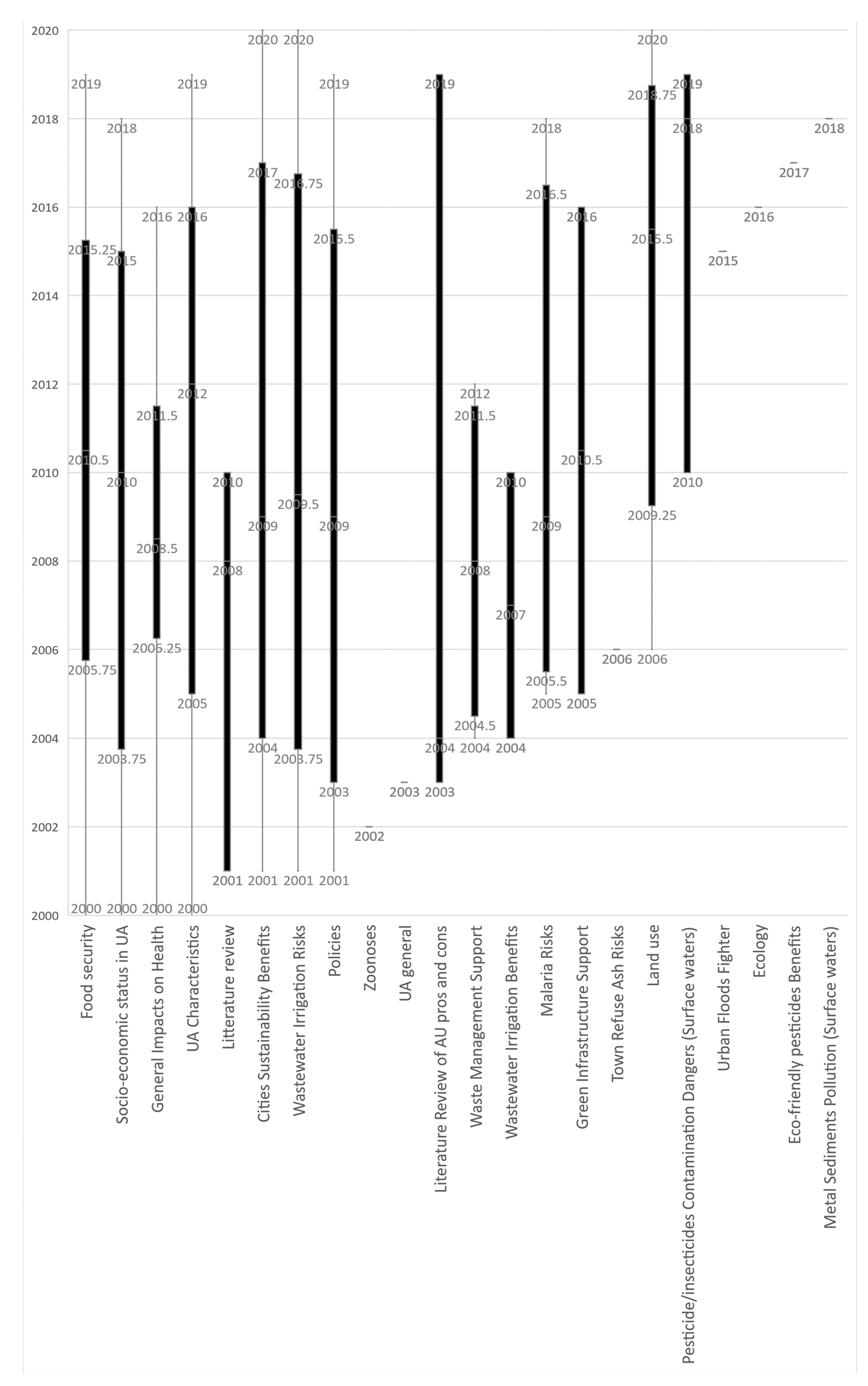

A chronological study was made to produce a representative graph of the evolution of the topics dealt with over the years (

Figure 5).

To categorize the studied publications, they were classified by general themes based on the main topics of their contents. Thus, 22 subtopics have been elaborated and classified by year and by number of appearances. The themes are as follows: Cities Sustainability Benefits, Wastewater Irrigation Risks, Policies, Zoonoses, UA general, Literature Review of UA pros and cons, Green Infrastructure Support, General Impacts on Health, Malaria Risks, Socio-economic status in UA, Land use, UA Characteristics, Pesticide/insecticides Contamination Dangers (Surface waters), Literature review, Waste Management Support, Town Refuse Ash Risks, Ecology, Urban Floods Fighter, Metal Sediments Pollution (Surface waters), Eco-friendly Pesticides Benefits, Wastewater Irrigation Benefits.

The following table (

Table 1) provides context or explanation for each theme or its significance.

These specific topics were picked up from the databases because they globalize other sub-themes within themselves, making it easy to explain the overall themes. They are relevant to the overall research in the sense that they synthesize several small themes addressed by the authors, and which if all listed, would be overwhelming for readers of this paper to grasp. The following graph shows the behavior of these UA trends throughout the years from 2000 to 2020.

In

Figure 5, black bars represent the number of studies published by field by year. The standard deviation (-) shows the measure of how dispersed the publication per discipline per year is in relation to the mean. This graph shows that among the 22 topics that emerged, “Food security”, of Cities Sustainability Benefits, Wastewater and of “Literature Review”, of Pros and Cons” are those that have been the most consistent, having been treated at least every year from 2000 to 2020.

As much as the topic “Literature Review of UA Pros and Cons”, publications concerning.

“Pesticide/insecticides Contamination Dangers (Surface waters)” are the ones that have gained the most popularity in recent years and since the 2010s. The subject of “Land Use” has also found some growth almost in parallel with the theme “Pesticide/insecticides Contamination Dangers (Surface waters)”.

Wastewater Irrigation Benefits have been the least discussed theme over time.

The topics of Metal Sediment Pollution, Waste Management and General Impacts on Health, and Food Security support have specifically gained interest in the last five years.

The questions of “Zoonoses”, “UA general”, and “Town Refuse Ash Risks” are the topics that have been punctually and very rarely handled during the period covered by this study of literature review.

4.6. Localization of the studied cases (only with Scopus, Web of Science and Pubmed data)

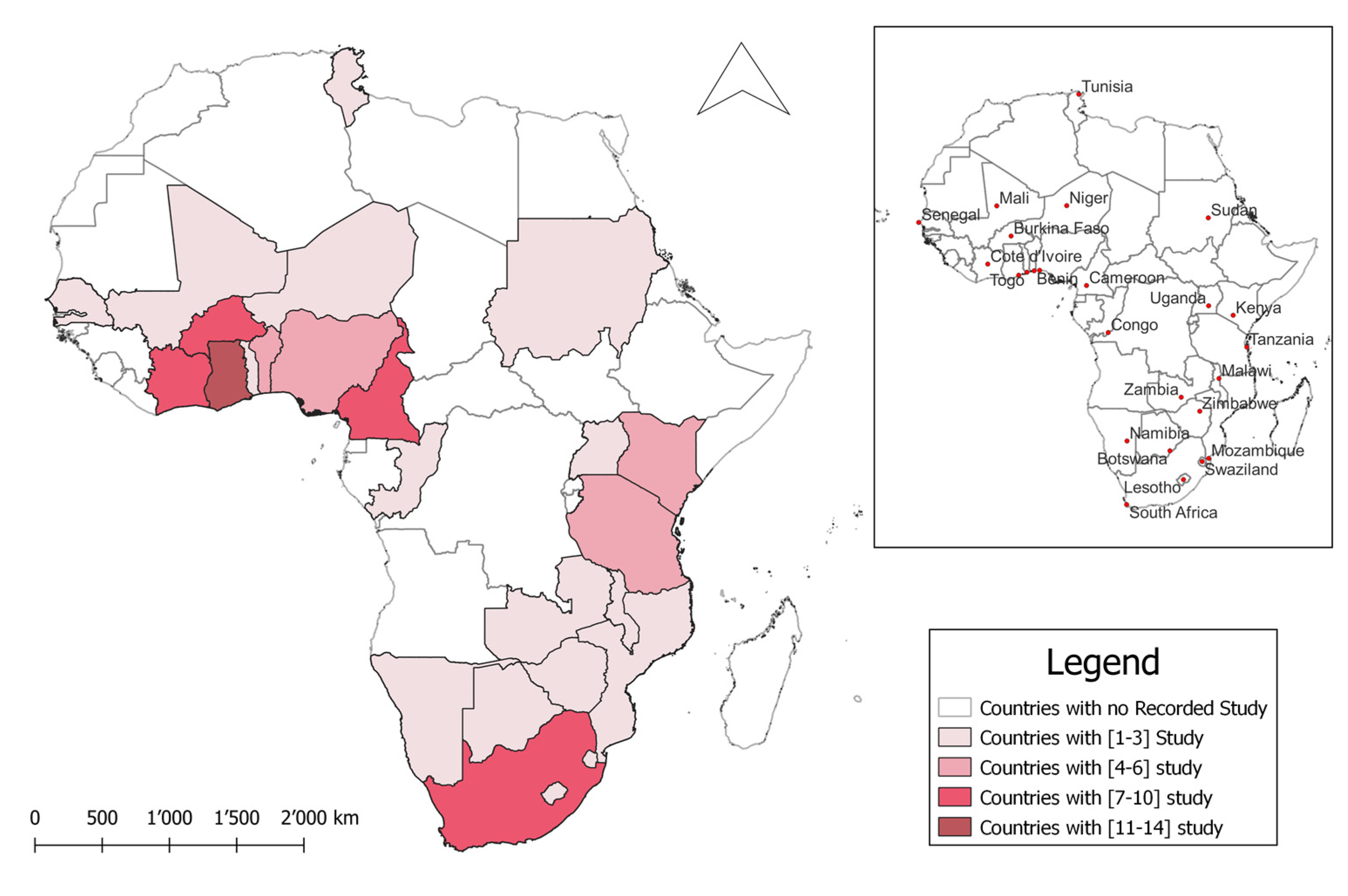

The case studies for the Scopus portal are mainly from Ghana (14%), Côte d’Ivoire (8%) and South Africa (8%). Some publications have dealt with regions rather than countries, but not all regions have official boundaries distinct from one another. These data have not been considered. These are “Africa” (n = 5), “Equatorial Africa” (n = 1), “Global South” (n = 1), “Intertropical Africa” (n = 1), “Sub-Saharan Africa” (n = 3), “West Africa” (n = 2). A map shows two major regions of concentration, West Africa, East and South Africa.

The Maghreb countries and Madagascar are hardly represented in the accounts. Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, and Burkina Faso are 3 border countries with a non-negligible number of publications on the subject. The same is true for Tanzania, Kenya, and Uganda.

It is also noted that among the most represented countries, most are of large land areas, such as South Africa, Tanzania, Kenya, Nigeria, and Cameroon. Referring to the map obtained after data visualization (

Figure 6), coastal countries also seem to have been especially studied about the subject.

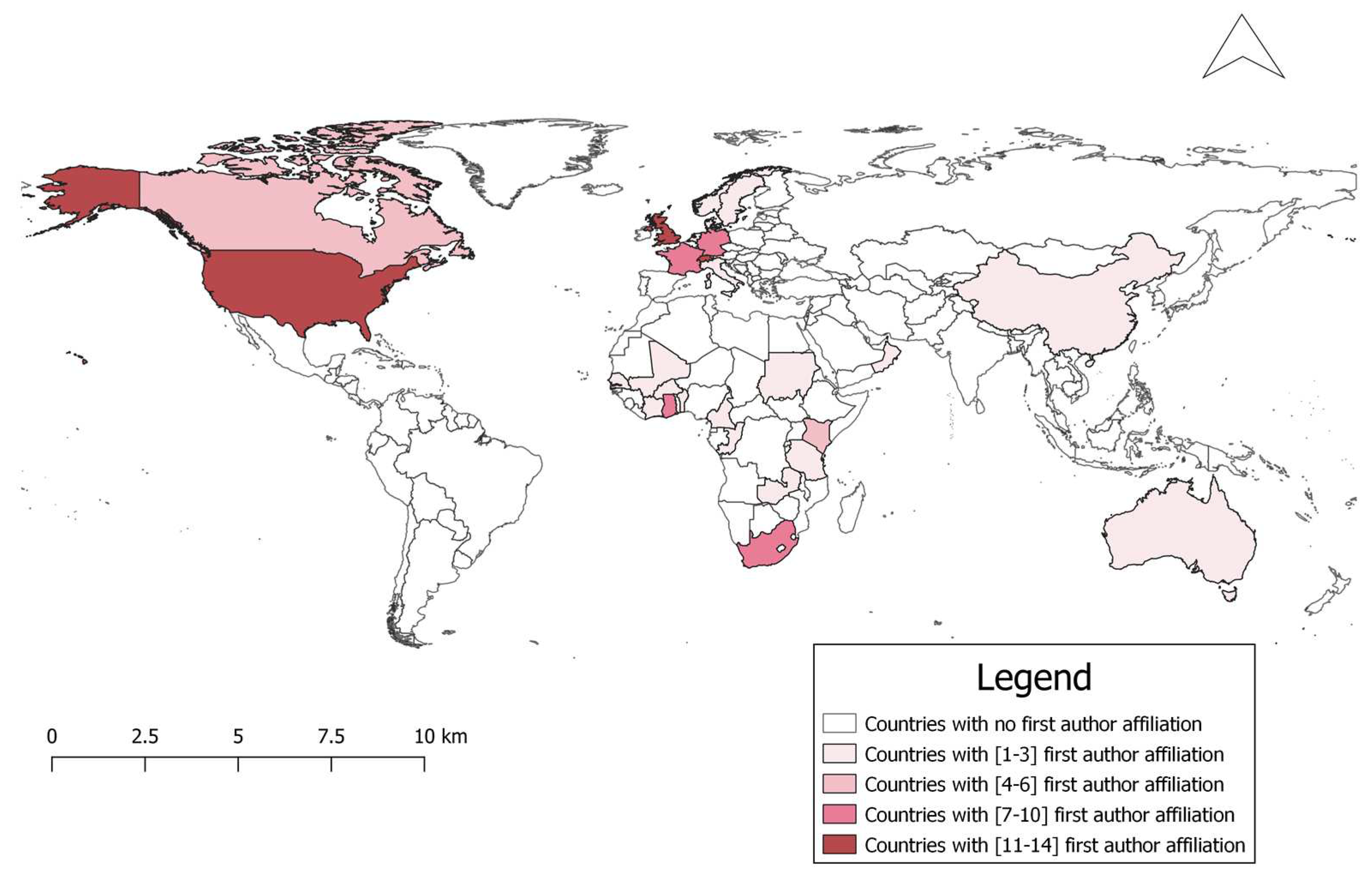

4.7. Affiliation of authors

Of the n = 115 publications collected and studied on Scopus, Pubmed and Web of Science, less than 20% were initiated by laboratories of affiliation of the first author located in Africa. This is shown in

Figure 7. Thus, the UK, the USA and Switzerland (maybe because of IP address located in Switzerland) are the countries that have dealt with the subject the most, with 16.1%, 14.95% and 14.95%, respectively. Even if they are not in the winning trio, South Africa and Ghana have the privilege to make 10% each of the sum of the publications.

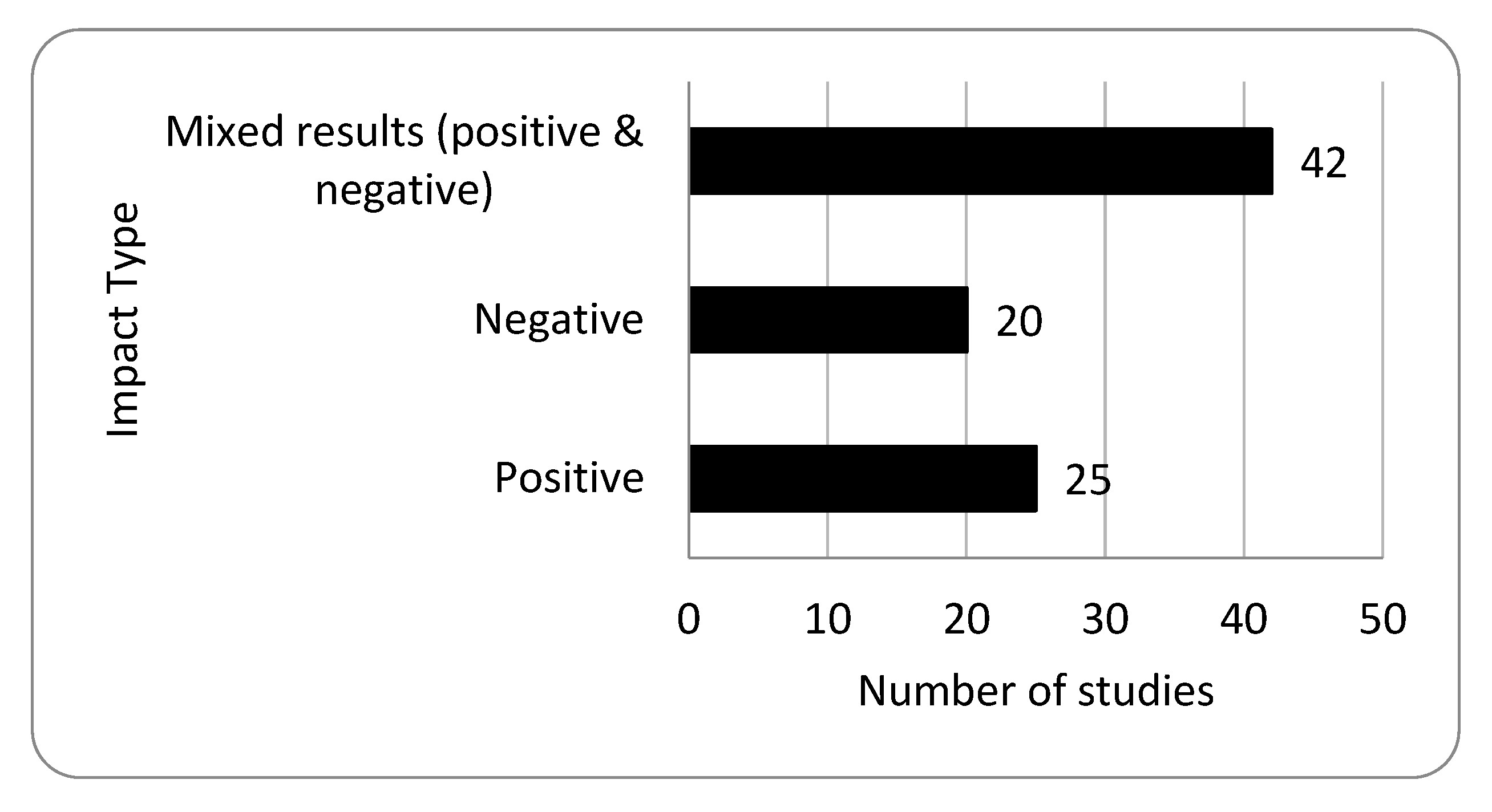

4.9. Does UA have a negative or a positive impact on health?

Finally, in this study, ‘positive impact’ is defined as a favorable effect or outcome of the practice of UA on the health of either farmers or consumers of the products of these crops. This definition contrasts with ‘negative impact’, an effect or outcome of UA that is detrimental to health. The third category, called “Positive & Risks”, is considered to encompass publications that have hypothesized both positive and negative health effects of UA.

Hence, how the results of this research are viewed about UA and its impacts on health in Africa was assessed in this research (

Figure 8). About 48% of the results speak of positive impacts but are accompanied by risks to be managed. 29% found that UA has totally positive effects on the health of urban dwellers, and 23% highlighted the negative effects of this practice in African cities.

5. Discussion of results

In this review of the Scopus, Pubmed, Web of Sciences and Google Scholar databases over the last two decades of publication on UA and Health in Africa, the analysis showed a growing interest in the research world and the lack of research done under the auspices of urban planning for this topic. The following lines put the results found above into perspective, in terms of specific objectives, recommendations and limitations.

5.1. Assessment of the general evolution of the interest in the UA-urban health linkages in recent decades (2000-2020)

5.1.1. The first place of scientific articles in systematic literature publications

The results of this part of the analysis legitimize that more master’s and PhD theses, reports, books, and conference papers on the subject would be welcome. Indeed, even though research has allowed itself to cast a wide net even in grey literature, articles have had supremacy over other types of publications on the subject, as they often do [

25].

Furthermore, it would be noteworthy to define exactly the target audience that would benefit from the study [

26]. Objectively, it would be primarily the urban producers and consumers of UA products in these African cities and experts in the field of urban planning, agriculture, and health. One possible explanation could be that databases receive far more articles for publication than any other type. Another could be that article, for example, take fewer resources of various kinds to write than books, and that books have an economic model that requires them to go through specific publishing houses. The case of theses could be linked to the fact that these productions are often not sent to journals, remaining most of the time in the libraries of the schools in which they are produced. As for conference papers, perhaps it’s because they often have fewer pages, and don’t meet all the criteria for publication in these databases.

5.1.2. UA and health topics gain ground

Considering the variation in the number of publications over the last 20 years, it is noticed that the subject is gaining interest, which denotes that the research presented here fits well into this dynamic.

This fact could be justified by the increase of ecological objectives in the agenda of international institutions, dragging a rise in funding for research projects related to urban agriculture and organic and ecological production [

27].

Also, the importance of greenery in general in cities concerning its myriad of benefits, and UA and its increasingly popular innovations, could contribute to the growth of interest in the subject [

28]. Or on the contrary, the risks posed by the practice of this activity in African cities, which make it controversial, could have led researchers and politicians to warn all stakeholders of this activity and the institutions on which it may depend [

29].

Another reason could simply be that the issue of food security is becoming more and more prominent in the literature, even among the SDGs. Many researchers might find themselves with more incentives to do research in this area.

It could also just be out of curiosity about how rapidly Africa’s urban population is evolving, while food sources and shelter are diminishing in quantity. Which might explain the need to look for solutions in advance of the catastrophe this could cause in several years’ time.

5.1.3. Many African countries are waiting to be studied

Countries such as Equatorial Guinea, Sao Tome and Principe, Namibia, Botswana, Mauritania, and Angola show a significant increase in urban population between 2000 and 2020 but have not been studied at all about UA and health in this period and according to the analyses of the databases studied.

Could this result be linked to the size of these countries, which don’t have enough land for UA? Or could it be because they don’t practice UA at all? Another possibility is that these countries may be applying so much modern urbanism, thinking that UA is like bringing the village back to the city. However, the more diverse the countries studied, the more credible the results will be due to the heterogeneity and robustness of the samples [

30,

31,

32].

5.1.4. The imbalance between the origin of the research laboratories

In terms of the results obtained, a mixed picture emerges regarding the number of publications from Africa. This is the case in virtually all other research areas and could be explained by the limited resources invested in research in the South. However, the hypothesis is that Africa would benefit from publishing much more in these areas of Urban Agriculture and Health studies in Africa. On the one hand, the studies would be even more relatable because they would have been developed by people immersed in the realities of the context [

33,

34,

35]. On the other hand, these publications could highlight innovations of which the Western world is not yet aware, confirming the concept of reverse innovation, which would consist of a South-North movement of “low-tech cut-edge” methods i.e., techniques that don’t require a great deal of material resources, but that solve real problems using technology [

36,

37].

Taking the specific cases of Tanzania, a largely English-speaking country in East Africa, and Togo, a small French-speaking country in West Africa, Tanzania is much better off than Togo as a field of study in this research area. This could be explained by the fact that local communities already support a lot of UA governance in Tanzania [

38]. Also, there is a growing number of international and civil society institutions promoting and implementing UA planning efforts in Tanzania [

5,

39,

40,

41,

42], while this topic remains embryonic in Togo. Moreover, Tanzania, as an Anglo-Saxon country, invests much more in research than Togo.

5.1.5. Mixed and qualitative methods are underrepresented

The results achieved suggest that applying qualitative or mixed methods would contribute to the field of research under this theme [

43,

44]. The superiority of the quantitative method may be since agriculture under this theme is viewed from a more health-related perspective. This is evidenced by the fact that the two primary research disciplines are public health, earth, and environmental sciences [

45]. This may have directed research on more quantitative methods.

However, of the two approaches to improve under the theme, the mixed method can be particularly positive because the mixed method in empirical research, usually translated into case studies [

46], has the privilege of showing a broader view of an issue at the case study level [

47]. The intersection of the results of the quantitative study and those of the qualitative study allows for harmonization and solidification of the results and, therefore, of the recommendations that could be drawn from them [

48].

In any case, the literature shows that the use of mixed methods has many advantages in scientific research.

5.1.6. Is “Food security” the first objective for which UA should be practised?

Considering all that the analysis of the topics has revealed, it could be fascinating to focus research to delve into the real aspects of the Food Security limited goal that UA can achieve in African countries [

49] to confirm or infirm the tendency, since research related to food security may appear to be obvious [

10].

If the planner’s point of view is to be considered, several theories are already confirmed about Food Security, with verification methods that are proving to be quite accessible to the planner, such as chronic disease primary and secondary data, based upon ethical methods [

50]. Though, it could also be great if there would be interest in researching a little more on policies or UA planning tools in general.

Still, it is probably fair to say that the most recent policy analysis comes from agricultural circles, much less from urban planning sectors. Without overlooking the critical contribution of the former, the latter is even more fundamental to UA’s adequate integration into the urban economic and ecological system [

51].

Another way is to check if other more subtle types of health outcomes are not relevant in African cities, as it is in Europe and in the US [

52]. As for a try, is psychological well-being related to the socio-economic impacts of UA on urban health worth the analysis, and is it equally distributed among genders among African urban farmers? [

53,

54,

55].

At all events, there is no clear study that indicates the food production capacity of a city, the better quality of this food compared to what is produced in rural areas per year for example. If these elements are proven, and all the other criteria for obtaining food security are also proven, then a result like the one currently obtained saying that food security is the first outcome of UA on health will be more convincing.

5.2. Assessment of the specific role of urban planners in the knowledge production on UA and health in Africa, by quantifying the number of works in this field, as compared to other fields: Urban planning, one of the poor relations in the literature on the subject

As far as it concerns this paper the most, this gathered information through the review analysis shows that there needs to be more research at the level of the Urban planning field. This is noticeable even if it is also shown that the subject “Land use” has been constantly used in the period considered by this study.

Is this lack of publication from the field of urban planning justified because there are fewer publications in general by architects, urban planners, or any other urban planning experts who do more “practice-based research”, which has been complained about [

56]? Or is it because agriculture is generally considered a rural activity [

57]? Or is it because research shows that it is a phenomenon that has always existed in African cities and is even expanding [

58,

59] that it doesn’t need that much attention?

Another thing that could support this is that architects and urban planners might be more interested in the operational side of their profession, for the immediate benefits that this can bring. In summary, one of the significant contributions of this article is not only its revelation of the growing importance of urban agriculture and its significant impact on public health but also its emphasis on the need for architecture and urban planning disciplines in Africa to take a greater and more concrete interest in this subject. This presents an additional empirical reason for integrating urban agriculture into their studies, planning documents, and development projects. The article also uncovers a new avenue of research in the field of urban science in Africa.

On one hand, it is generally understood that urban agriculture typically requires land for cultivation [

18,

23]. Hence, it is important for the subject of urban agriculture to be adequately discussed in architecture and urban planning studies [

60]. On the other hand, health has been a fundamental consideration in early urban planning [

61]. Studies clearly indicate that urban agriculture involves health issues and is an integral part of urban life [

62]. However, this study demonstrates that urban planning experts do not show sufficient interest in urban agriculture as a mediator of urban health [

63].

To address this weakness, several initiatives could be undertaken by urban planning specialists [

64]. These include zoning urban agriculture within the urban fabric and providing infrastructure and networks, such as drinking water and electricity for watering plants, which fall under the purview of urban planners and architects [

65]. Additionally, regulations could offer incentives for integrating urban agriculture as closely as possible to the inhabitants, promoting the use of soil-less, rooftop, and wall-mounted cultivation innovations to optimize surface area [

66]. Furthermore, efforts to combat the use of toxic products can be undertaken with the support of institutions responsible for agriculture and health [

67].

5.3. Establishment of an overview of the positive and negative health impacts of UA in African cities

5.3.1. The negative health impacts of UA are not negligible

This study reveals that the topics that have been the most constant over more than 10 years in a row are Waste Management Support, Wastewater Irrigation Risks, Pesticides/Insecticides, and Contamination Dangers, and almost all between 2007 and 2020. Would this explain that the dangers that UA may represent for human health do exist and that they should be given a little more attention to the topics to be dealt with under the global umbrella of UA and health [

51]? This could be a salutary response to the growing injunction to grow food in cities, which should consider the precautions to be taken to avoid making them a cause of urban health degradation [

68].

However, if research continues this negative note, would there be a chance that UA would lead to fewer urban health problems? Especially if this induces that the city is planned in conjunction with planning UA. Holistically, considering institutional, policy and spatial planning aspects, provide tools to raise awareness of urban farmers, provide subsidies to access cleaner and safer plant health products, reserving UA land in the healthiest possible locations within the city and provided with clean water [

69].

5.3.2. Researchers are actually looking at UA from a dual perspective in terms of its health impacts

Based on these data illustrating the study contexts of the subject, it appears that UA does have both positive and negative impacts on human health in Africa, and in almost equal proportions [

70]. Urban planning discipline is said to have still room to study the subject of UA and health, to reveal the urban planning factors that mitigate the risks or enhance the benefits of UA in African cities as it is being studied in western areas [

71].

Either way, given that the two types of impact are sufficiently documented in the literature, this confirms that both elements are to be taken seriously. This result of the analysis is therefore indicative of a gap to be filled in terms of research on UA impacts.

5.3. Recommandations

The recommendations from the discussion would be to initiate more master’s theses and doctoral dissertations on the triptych of UA, health, and urban planning; for practitioners to work more with the subject in creating and using their tools; to use mixed methods adapted to the socio-economic and cultural realities of Africa. The mixed method may help to move towards a balance of method types in this kind of research.

In addition, taking advantage of the growing ubiquity of information and communication technologies in Africa, alternative channels of publication, as demonstrated by [

72], it would be beneficial for experts in urban planning in Africa to become more interested in studying the topic of UA and health, and in so doing, give equal importance to the positive and negative impacts of research on UA and health. The choice of increasingly contemporary formats and publication channels, such as instructional visual content and social networks, could be more and more adapted to the reality [

69,

72,

73]. With the increasing disruption of technological tools, such as smartphones and their applications in Africa, African scientists can seize these means to increase their visibility in general and publish about UA and health [

73,

74]. This would also allow them to reach as many of their target population as possible.

Another recommendation is that many African countries would benefit from research on UA and health, so the results must be as comprehensive as possible. By the way, scientists from laboratories in African countries would be best placed to research the subject in Africa for results that consider the realities of the people immersed.

Integrating innovative practices such as vertical farming or hydroponics and aeroponics to minimize the risks of contamination from the immediate environment and respond to the growing land scarcity are possible other solutions [

74]. Also, future studies on this topic could add value by adopting the mixed method. This approach would also promote multidisciplinary, which is increasingly recommended in scientific research [

75,

76,

77].

Moreover, it appears from the analysis that UA has a mitigated impact on health. Therefore, researching if the integration of UA into urban planning tools like master plans alleviates risks or enhances the benefits of UA concerning the food security health indicators of the people could be a valuable topic that will bring something new to scientific research. It would also be legitimate not to focus on only one type of impact, but to continue to study them in parallel, to determine how negative impacts can be mitigated and positive impacts enhanced [

74].

5.4. Limitations

The typological, chronological, thematic, geographic, and methodological analyses in our research offer the possibility of hypothesizing about the characteristics of the literature on UA and health in Africa, it is important to identify biases that may have influenced the outcomes. The findings should therefore be considered in this context.

One of the areas for improvement is that the articles were selected from the databases without being separated by metadata, such as their impact on publications and their citation metrics.

Also, as the analyses were done manually, and Google Scholar did not automatically provide the main fields of study of the author in the columns of the CSV file provided through Zotero, only Scopus, Web of Science and Pubmed data were used for the “main field of affiliation of authors” analysis and the methodological one. The “chronological evolution analysis of topics” was only based on Scopus alone, the first ranked on the list of databases.

In addition, only data from Scopus, Web of Science and PubMed were used for certain analyses, to the exclusion of other databases. This may limit the completeness and representativity of the results, as important publications from other sources may have been ignored.

Another limitation is that the databases from which the data were extracted are mostly in English. Google Scholar offered articles in other languages, but the search form was elaborated in English, using a simple and easy-to-replicate method, to harmonize things, especially since our search is also conducted in English. The results might have been different, for example, in terms of the countries of the study sites or the affiliations of the authors. For example, it could be that the predominant language of the publication databases used is English, so Tanzania was favored over Togo, a country whose official language is French. The same study conducted on French-only databases could resolve this ambiguity and confirm or refute the results of the present study. Other research initiatives could be conducted in other languages or in a more comprehensive manner to compare results. A review could also consider other publication platforms to diversify the sources.

One limitation is that the publications studied come from both peer-review and gray literature. This may mean that academic rigor was not applied equally to all publications. Also, the search equation was not adapted to each database. This could have produced a different result. Another limitation is that only one researcher collected, extracted, analyzed, and interpreted the data. This may mean that some relevant studies have been omitted.

Finally, this article was written several months after the data was collected, and with the evolution of artificial intelligence, for example, some data might have changed when applying the research equation, and interpretations might have been different.

6. Conclusions

This paper makes an empirical analysis of the publications of UA studies in Africa that are related to the theme of health and sees how much they are related to the Urban Planning field. Regarding results, it is noted that journal articles are the ones that are most concentrated on the subject, at the expense of doctoral or master’s theses. The data also show that the topic is gaining popularity over time and that the discipline of Public Health, Environmental Science and Agriculture, respectively talk more about UA than any other discipline, and that Architecture and Urban Planning would benefit from publishing more peer review work on the topic. As the primary health goal of UA, food security is the most popular theme. However, studies uncover a consequent need of interest for waste management, wastewater irrigation hazards and pesticide contamination hazards. Finally, the most used research methods are quantitative first and qualitative second and very few research projects employ a mixed and comparative method.

The added value of the paper is to reveal the growing importance of the topic of UA and its significant impacts on public health. Another is to expose the need for the architectural and urban planning discipline in Africa to take a greater and more concrete interest in the topic and incorporate it into their studies, planning documents and development projects. The paper reveals an additional avenue of research in African urban science. The implementation of these recommendations from this study will help provide a more legitimate framework for UA in the African urban landscape to reduce the health risks it poses while increasing the likelihood that the positive impacts of UA on urban health will be optimal for the well-being of all city dwellers, and why not, the entire territory. Hence, urban experts will have contributed through UA planning to keeping the African city and the world city, in general, as healthy as possible. They will have helped the city to breathe, to eat, to be better and, quite simply, to live.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Konou, A.A. and Chenal, J.; methodology, Konou, A.A. and Kemajou Mbianda; software, Konou, A.A.; validation, Chenal, J., Munyaka, B.J-C and Kemajou Mbianda, A.F.; formal analysis, Konou, A.A., Kemajou Mbianda, A.F., Munyaka, B.J-C and Chenal, J.; investigation, Konou, A.A.; resources, Chenal, J.; data curation, Konou, A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, Konou, A.A.; writing—review and editing, Konou, A.A., Kemajou Mbianda, A.F., Munyaka, B.J-C and Chenal, J.; visualization, Konou, A.A.; supervision, Chenal, J., Munyaka, B.J-C, and Kemajou Mbianda, A.F.; project administration, Chenal, J.; funding acquisition, Chenal, J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was totally supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF#18357) Sinergia Project—African Contribution to Global Health: Circulating Knowledge and Innovations (https://www.globalhealthafrica.ch/).

Data Availability Statement

Data Citation: Konou, Akuto Akpedze, Kemajou Mbianda, Armel Firmin, Baraka Jean-Claude Munyaka & Chenal, Jérôme. (2023). Urban Agriculture and Health in Africa. A Review. [Data set]. Zenodo.

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8043945.

Acknowledgments

The authors like to show their gratitude to Vitor Pessoa Colombo, Remi Jaligot, Marti Bosch, Ximena Salgado Uribe, Pablo Txomin Harpo de Roulet, Salifou Ndam, Gladys Ninoles, Carine Micheloud from the CEAT team, and Afriyie, Prof. Dr. Jürg Utzinger, Dr. Doris Osei and Dr. med. Ipyn Eric Newbie from the Swiss TPH team, Prof Dr. Julia Tischler, Dr. Tanja Hammel, and Dr. Danelle van Zyl-Hermann from the University of Basel for guiding and supporting them throughout the data collection, writing, and review process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tasciotti, L.; Wagner, N. Urban Agriculture and Dietary Diversity: Empirical Evidence from Tanzania. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2015, 27, 631–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arku, G.; Mkandawire, P.; Aguda, N.; Kuuire, V. Africa’s Quest for Food Security : What Is the Role of Urban Agriculture? 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sibhatu, K.T.; Qaim, M. Rural Food Security, Subsistence Agriculture, and Seasonality. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0186406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhé-Beaulaton, D. Approche historique de l’agriculture urbaine au Dahomey (Bénin). Rev. D’ethnoécologie, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drechsel, P.; Dongus, S. Dynamics and Sustainability of Urban Agriculture: Examples from Sub-Saharan Africa. Sustain. Sci. 2010, 5, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, J.A.; Sweeney, E.; Wong, B.; Sia, C.S.; Yao, H.; Prabhudesai, M. Feeding Cities: Singapore’s Approach to Land Use Planning for Urban Agriculture. Glob. Food Secur. 2020, 26, 100377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulighe, G.; Lupia, F. Food First: COVID-19 Outbreak and Cities Lockdown a Booster for a Wider Vision on Urban Agriculture. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Feeding 11 Billion on 0.5 Billion Hectare of Area under Cereal Crops. Food Energy Secur. 2016, 5, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeng-Odoom, F. Underwriting Food Security the Urban Way: Lessons from African Countries. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2013, 37, 614–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zezza, A.; Tasciotti, L. Urban Agriculture, Poverty, and Food Security: Empirical Evidence from a Sample of Developing Countries. Food Policy 2010, 35, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagendra, H.; Bai, X.; Brondizio, E.S.; Lwasa, S. The Urban South and the Predicament of Global Sustainability. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, F.; Müller, F.; Haase, D.; Fohrer, N. Rural–Urban Gradient Analysis of Ecosystem Services Supply and Demand Dynamics. Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.D. Commentary: Behind the Broad Street Pump: Aetiology, Epidemiology and Prevention of Cholera in Mid-19th Century Britain. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2002, 31, 920–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoh, A.J. Urban Planning as a Tool of Power and Social Control in Colonial Africa. Plan. Perspect. 2009, 24, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryld, E. Potentials, Problems, and Policy Implications for Urban Agriculture in Developing Countries. Agric. Hum. Values 2003, 20, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mougeot, L.J.A.; Centre (Canada), I.D.R. Growing Better Cities: Urban Agriculture for Sustainable Development; IDRC, 2006; ISBN 978-1-55250-226-6.

- Grimm, N.B.; Foster, D.; Groffman, P.; Grove, J.M.; Hopkinson, C.S.; Nadelhoffer, K.J.; Pataki, D.E.; Peters, D.P. The Changing Landscape: Ecosystem Responses to Urbanization and Pollution across Climatic and Societal Gradients. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2008, 6, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mougeot, L.J.A. Agropolis: The Social, Political, and Environmental Dimensions of Urban Agriculture; IDRC, 2005; ISBN 978-1-55250-186-3.

- Azzopardi-Muscat, N.; Brambilla, A.; Caracci, F.; Capolongo, S. Synergies in Design and Health. The Role of Architects and Urban Health Planners in Tackling Key Contemporary Public Health Challenges. Acta Bio Medica Atenei Parm. 2020, 91, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verzone, C.; Woods, C. Food Urbanism: Typologies, Strategies, Case Studies. In Food Urbanism; Birkhäuser, 2021 ISBN 978-3-0356-1567-8.

- Hermand, M.-H. Manola Antonioli, Guillaume Drevon, Luc Gwiazdzinski, Vincent Kaufmann, Luca Pattaroni (dirs), Saturations. Individus, collectifs, organisations et territoires à l’épreuve. Quest. Commun. 2020; 682–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guitart, D.; Pickering, C.; Byrne, J. Past Results and Future Directions in Urban Community Gardens Research. Urban For. Urban Green. 2012, 11, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viljoen, A.; Bohn, K. Second Nature Urban Agriculture: Designing Productive Cities; Routledge, 2014; ISBN 978-1-317-67451-1.

- Audate, P.P.; Fernandez, M.A.; Cloutier, G.; Lebel, A. Scoping Review of the Impacts of Urban Agriculture on the Determinants of Health. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastel, B.; Day, R.A. How to Write and Publish a Scientific Paper, 9th Edition; ABC-CLIO, 2022; ISBN 978-1-4408-7883-1.

- Stern, B.M.; O’Shea, E.K. A Proposal for the Future of Scientific Publishing in the Life Sciences. PLOS Biol. 2019, 17, e3000116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenle, A.A.; Wedig, K.; Azadi, H. Sustainable Agriculture and Food Security in Africa: The Role of Innovative Technologies and International Organizations. Technol. Soc. 2019, 58, 101143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azunre, G.A.; Amponsah, O.; Peprah, C.; Takyi, S.A.; Braimah, I. A Review of the Role of Urban Agriculture in the Sustainable City Discourse. Cities 2019, 93, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidner, T.; Yang, A.; Hamm, M.W. Consolidating the Current Knowledge on Urban Agriculture in Productive Urban Food Systems: Learnings, Gaps and Outlook. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 1637–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndt, A.E. Sampling Methods. J. Hum. Lact. 2020, 36, 224–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdar, C.C.; Cihan, M.; Yücel, D.; Serdar, M.A. Sample Size, Power and Effect Size Revisited: Simplified and Practical Approaches in Pre-Clinical, Clinical and Laboratory Studies. Biochem. Medica 2021, 31, 010502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakens, D. Sample Size Justification. Collabra Psychol. 2022, 8, 33267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenal, J.; Radoine, H.; Kemajou, A.F.; Jaligot, R.; Yakubu, H.; Mrani, R. Apprendre des villes africaines. Afr. Cities J. 2020, 1, 7–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, A.; Konou, A.A.; Meier, L.; Brattig, N.W.; Utzinger, J. More than Seven Decades of Acta Tropica: Partnership to Advance the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Acta Trop. 2022, 225, 106175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, N.; Patil, S.; Singh, C.; Roy, P.; Pryor, C.; Poonacha, P.; Genes, M. Cultivating Sustainable and Healthy Cities: A Systematic Literature Review of the Outcomes of Urban and Peri-Urban Agriculture. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 85, 104063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Et Si Les Villes Étaient plus Résilientes En Afrique Qu’en Europe? Le Temps 2021.

- Kemajou, A.; Konou, A.A.; Jaligot, R.; Chenal, J. Analyzing Four Decades of Literature on Urban Planning Studies in Africa (1980–2020). Afr. Geogr. Rev. 2021, 40, 425–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergius, M.; Benjaminsen, T.A.; Maganga, F.; Buhaug, H. Green Economy, Degradation Narratives, and Land-Use Conflicts in Tanzania. World Dev. 2020, 129, 104850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersaglio, B.; Kepe, T. Farmers at the Edge: Property Formalisation and Urban Agriculture in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. Urban Forum 2014, 25, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halloran, A.; Magid, J. Planning the Unplanned: Incorporating Agriculture as an Urban Land Use into the Dar Es Salaam Master Plan and Beyond. Environ. Urban. 2013, 25, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halloran, A.; Magid, J. The Role of Local Government in Promoting Sustainable Urban Agriculture in Dar Es Salaam and Copenhagen. Geogr. Tidsskr.-Dan. J. Geogr. 2013, 113, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Magigi, W.; Godfrey, B. The Organization of Urban Agriculture: Farmer Associations and Urbanization in Tanzania. Cities 2015, 42, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelle, U. Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Research Practice: Purposes and Advantages. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 293–311. [Google Scholar]

- Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Johnson, R.B.; Collins, K.M. Call for Mixed Analysis: A Philosophical Framework for Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Int. J. Mult. Res. Approaches 2009, 3, 114–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mays, N.; Pope, C. Quality in Qualitative Research. In Qualitative Research in Health Care; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2020; pp. 211–233 ISBN 978-1-119-41086-7.

- Fetters, M.D.; Curry, L.A.; Creswell, J.W. Achieving Integration in Mixed Methods Designs-Principles and Practices. Health Serv. Res. 2013, 48, 2134–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Barriers to Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2007, 1, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Leech, N.L. On Becoming a Pragmatic Researcher: The Importance of Combining Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methodologies. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badami, M.G.; Ramankutty, N. Urban Agriculture and Food Security: A Critique Based on an Assessment of Urban Land Constraints. Glob. Food Secur. 2015, 4, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee-Smith, D. Cities Feeding People: An Update on Urban Agriculture in Equatorial Africa—Diana Lee-Smith, 2010. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0956247810377383 (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Menyuka, N.N.; Sibanda, M.; Bob, U. Perceptions of the Challenges and Opportunities of Utilising Organic Waste through Urban Agriculture in the Durban South Basin. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilieva, R.T.; Cohen, N.; Israel, M.; Specht, K.; Fox-Kämper, R.; Fargue-Lelièvre, A.; Poniży, L.; Schoen, V.; Caputo, S.; Kirby, C.K.; et al. The Socio-Cultural Benefits of Urban Agriculture: A Review of the Literature. Land 2022, 11, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-A.; Lee, A.-Y.; Son, K.-C.; Lee, W.-L.; Kim, D.-S. Gardening Intervention for Physical and Psychological Health Benefits in Elderly Women at Community Centers. HortTechnology 2016, 26, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, G.; Mazzocchi, C.; Corsi, S. Urban Gardeners’ Motivations in a Metropolitan City: The Case of Milan. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, J.L.; Thirlaway, K.J.; Backx, K.; Clayton, D.A. Allotment Gardening and Other Leisure Activities for Stress Reduction and Healthy Aging. HortTechnology 2011, 21, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luck, R. Design Research, Architectural Research, Architectural Design Research: An Argument on Disciplinarity and Identity. Des. Stud. 2019, 65, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, L.; Elgert, L.; WinklerPrins, A. Theorizing Urban Agriculture: North–South Convergence. Agric. Hum. Values 2020, 37, 869–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prain, G.; Lee-Smith, D. Urban Agriculture in Africa: What Has Been Learned. In African Urban Harvest: Agriculture in the Cities of Cameroon, Kenya and Uganda; Prain, G., Lee-Smith, D., Karanja, N., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, 2010; pp. 13–35. ISBN 978-1-4419-6250-8. [Google Scholar]

- Frayne, B.; McCordic, C.; Shilomboleni, H. Growing Out of Poverty: Does Urban Agriculture Contribute to Household Food Security in Southern African Cities? Urban Forum 2014, 25, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giseke, U.; Gerster-Bentaya, M.; Helten, F.; Kraume, M.; Scherer, D.; Spars, G.; Amraoui, F.; Adidi, A.; Berdouz, S.; Chlaida, M.; et al. Urban Agriculture for Growing City Regions: Connecting Urban-Rural Spheres in Casablanca; Routledge, 2015; ISBN 978-1-317-91013-8.

- Frumkin, H.; Frank, L.D.; Jackson, R.J. Urban Sprawl and Public Health: Designing, Planning, and Building for Healthy Communities; Island Press, 2004; ISBN 978-1-55963-305-5.

- Coley, D.; Howard, M.; Winter, M. Local Food, Food Miles and Carbon Emissions: A Comparison of Farm Shop and Mass Distribution Approaches. Food Policy 2009, 34, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follmann, A.; Willkomm, M.; Dannenberg, P. As the City Grows, What Do Farmers Do? A Systematic Review of Urban and Peri-Urban Agriculture under Rapid Urban Growth across the Global South. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 215, 104186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berke, P.R. Does Sustainable Development Offer a New Direction for Planning? Challenges for the Twenty-First Century. J. Plan. Lit. 2002, 17, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomaier, S.; Specht, K.; Henckel, D.; Dierich, A.; Siebert, R.; Freisinger, U.B.; Sawicka, M. Farming in and on Urban Buildings: Present Practice and Specific Novelties of Zero-Acreage Farming (ZFarming). Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2015, 30, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritts, M. Amplifying Environmental Politics: Ocean Noise. Antipode 2017, 49, 1406–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornaghi, C. Critical Geography of Urban Agriculture. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2014, 38, 551–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, J.; Cilliers, E.J.; Cilliers, S.S.; Lategan, L. Sustainability | Free Full-Text | Food for Thought: Addressing Urban Food Security Risks through Urban Agriculture. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/3/1267 (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Pal, H.; Chatterjee, A.; Debnath, S. Implication of Urban Agriculture and Vertical Farming for Future Sustainability. Chapters 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, C.K.; Specht, K.; Fox-Kämper, R.; Hawes, J.K.; Cohen, N.; Caputo, S.; Ilieva, R.T.; Lelièvre, A.; Poniży, L.; Schoen, V.; et al. Differences in Motivations and Social Impacts across Urban Agriculture Types: Case Studies in Europe and the US. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 212, 104110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langemeyer, J.; Madrid-Lopez, C.; Mendoza Beltran, A.; Villalba Mendez, G. Urban Agriculture — A Necessary Pathway towards Urban Resilience and Global Sustainability? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 210, 104055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido, C.M.; Redondo-Sama, G.; Sordé-Martí, T.; Flecha, R. Social Impact in Social Media: A New Method to Evaluate the Social Impact of Research | PLOS ONE Available online:. Available online: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0203117 (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Pulido, C.M.; Redondo-Sama, G.; Sordé-Martí, T.; Flecha, R. Social Impact in Social Media: A New Method to Evaluate the Social Impact of Research. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0203117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsini, F.; Kahane, R.; Nono-Womdim, R.; Gianquinto, G. Urban Agriculture in the Developing World: A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 33, 695–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research; SAGE Publications, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4833-5905-2.

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.B.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J. Mixed Methods Research: A Research Paradigm Whose Time Has Come. Educ. Res. 2004, 33, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).