INTRODUCTION

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) was attributed to more than 1.2 million deaths globally in 2019 according to the landmark GRAM (Global Research on Antimicrobial Resistance) study [

1]. Indiscriminate use of antimicrobials is the major driving force for extensive emergence and spread of multi-drug resistant (MDR) and extensively drug resistant (XDR) pathogens in India. [

2,

3]. Antimicrobials’ consumption witnessed a startling rise globally (65%) as well as in India (103%) between 2000 and 2015 [

4]. Such serious affairs regarding rampant antimicrobial use and alarming rise in AMR have stemmed numerous international and national initiatives [5-9], India being no exception [10-12]. “Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance (GAP-AMR)” was launched by WHO in 2015 [

5], followed by India’s “National Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance” in 2017 (2017-2021) [

10] to fight the AMR pandemic. Few strategic priorities listed under NAP-AMR include improving awareness and understanding of AMR amongst all stakeholders through effective information, education and communication (IEC) resources; and optimising the use of antimicrobials through strengthening antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) in healthcare [

10]. Besides these, WHO AWaRe (access, watch and reserve) classification of antibiotics is an effective tool towards tackling the menace of AMR and promoting ASPs especially in

Low and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) [

11]

.

Behavioural characteristics of both physicians and patients contribute to unnecessary antibiotic prescribing patterns as prescribers’ practices are usually influenced by patient expectations and requests. Various factors governing the healthcare professionals’ prescribing behaviours and how these relate to knowledge and attitude regarding AMR need to be understood if successful strategies to contain AMR are to be designed and implemented at regional and national levels. In this direction, surveys conducted among physicians in developed nations [13-16]and LMICs [17-19], in particular, highlight the fact that the non-judicious antimicrobial prescribing practices among prescribers are often attributable to lacunae in knowledge about AMR and optimal use of antimicrobials, including antibiotics. Few studies have argued on failure of adequate translation of knowledge of AMR into a reduction in prescribing and dispensing of antimicrobials [20-23]. An online survey-based study of physicians from seven countries of Asia Pacific region reported the physicians in India to be high prescribers [

24]. Thakolkaran et al conducted a KAP (knowledge, attitude and practices) study among 350 physicians in South India and reported that the physician’s knowledge of resistance patterns of common bacteria was related to receiving periodic updates on resistance patterns of bacteria and participation in courses on antibiotics [

21]. Another study reported high scores in knowledge and attitude scores among physicians in West Bengal though poor performance in practices. Although many doctors exhibited knowledge with respect to indications of antibiotics, however over 87% reported prescribing antibiotics for viral infections [

25]. In another survey involving 539 intensivists across India, Gupte et al reported high levels of variability in the prescription patterns advocating the need of antibiotic stewardship to standardize antibiotic prescriptions not only for efficacy but also to reduce the burden of multiple drug resistance [

26]. Few other studies also reported the knowledge on AMR and antibiotic prescribing patterns among physicians in different settings in India [

27,

28].

Most of the earlier studies in India were conducted at local or regional levels involving different subsets of physicians and hence fail to provide a comprehensive picture regarding physicians’ knowledge, perceptions and prescribing practices across the country and variations, if any among different zones or physicians attributes. Hence, this survey was designed to provide an up-to-date estimate of the knowledge, attitude and antibiotic prescribing behaviour of physicians across India. The survey findings would inform research and guide development of strategies, intervention, and policies for the containment of AMR in India.

METHODS

Study Design

A cross-sectional study was conducted among allopathy physicians from government and private sectors across India between May to July 2022.

Sample size calculation

Sample size for the present study was based on the proportion of the respondents perceiving AMR to be a problem in their own setting. Assuming this proportion to be 50% (a conservative choice since there is no nation-wide data in this regard), the minimum required sample size was estimated to be 384 with a 50% proportion rate, 5% absolute precision, and 95% confidence level using the formula:

Sample size

n = [DEFF*Np(1-p)]/ [(d

2/Z

21-α/2*(N-1)+p*(1-p)] [

29].

The design effect was kept at 1.0. Considering 25% non-response rate, the required sample size was 512. We recruited a total of 544 physicians out of 710 physicians contacted during May to July 2022 of which 432 physicians were from Government sector and 112 were from private sector.

Recruitment of Study Subjects

Physicians (N = 544) were recruited from an online survey via a self-reported questionnaire through social media like WhatsApp, Facebook, and Twitter. For survey, the country (India) was divided into 5 zones – North, East, West, South and Central zone. Physicians who have at least completed MBBS (Bachelors of Medicine and Bachelors of Surgery) and who are currently residing in India were included in the study. The questionnaire in English language prepared in Google Forms was sent to physicians across India by sharing link through contacts of physicians. Thus, primarily a convenient sampling technique was used. Further, the snowball sampling technique was used for enlisting additional participants, where the invited participants were requested to pass on the invitations to their peers. The initial part of the questionnaire included the consent to participate in the study. After consent is provided, then next questions appeared in the questionnaire and the participants filled their responses for each questions.

Study Questionnaire

A semi-structured self-administered pre-tested questionnaire in English language was used as data collection tool. The questionnaire comprised 35 questions grouped into 4 sections: Section 1 (9 questions) on socio-demographic characteristics such as name, age, gender, highest educational qualification, designation, department, affiliation, years of practice and residence; section 2 (11 questions) on knowledge of antibiotics use and resistance; section 3 (6 questions) on attitude of physicians toward antibiotic prescription; and section 4 (9 questions) on physician antibiotic prescribing behaviours in regular practice. The questionnaire was prepared after literature review of similar studies. The preliminary draft of the questionnaire was reviewed by five expert researchers in the field of clinical pharmacology, infectious diseases, epidemiology, public health and internal medicine to identify ambiguity and content validity. In a pilot study, this questionnaire was then pre-tested among 20 physicians who were not part of the study to assess its duration, clarity, sequence and feasibility. Necessary modifications were made before sending out the final questionnaires to respondents.

Participants’ knowledge on antibiotics use and resistance was assessed by a set of 11 questions covering factors promoting AMR, antibiograms, WHO AWaRe classification of antibiotics, agents effective against anaerobes, intravenous to oral switch of antibiotics. A score of 1 was given for correct responses while each wrong or do not know answer was scored as 0. One question (as per your knowledge, which is the most prescribed antibiotic in COVID-19 pandemic) was not included for scoring while score of 0 to 3 was given for one multiple choice question with three correct options; hence the overall knowledge score ranged from 0 to 12.

Attitude was assessed by a set of 6 positive and negative attitude questions in the form of yes/no/don’t know (do you think that your antibiotic prescribing behaviour has an impact on the development of antibiotic resistance in your region?; scored 0 or 1), multiple choice questions [who among the following can play a key role in addressing the issue of antibiotic resistance (scored 1 to 7); which of the following strategies can help in addressing the issue of antibiotic resistance (scored 1 to 4)] and on five-point likert’s scale (strongly agree/ agree/ neither agree nor disagree/ disagree/ strongly disagree; scored 1 to 5). Overall attitude scores ranged from 5 to 27; higher the score more positive the attitude.

Practice was assessed by 9 questions: on four- point likert’s scale (always/ sometimes/ rarely/ never; scored 1 to 4), yes/ no/ don’t know (do you ever employ delayed/ back-up antibiotic prescribing in your clinical practice) and multiple-choice questions (which sources of information do you mostly use while making decisions on antibiotic prescription, which factor/s mostly determine your choice of antibiotics; not included in scoring). Also, the participants were asked if they had attended any trainings/conferences to update their knowledge on antibiotic use during last 12 months. Overall practice score ranged from 5 to 21 with higher scores indicating good practices.

Using modified Bloom’s cut-off point, the percentage knowledge, attitude and practice scores were grouped into good (scores between 80 and 100%), average (scores between 50 and 79%) and poor (less than 50%) [

30].

Statistical Analysis

Through Google form, the data were captured in Microsoft Excel 2021 and were analysed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences [SPSS (Trial v. 28)]. Appropriate tables and graphs were prepared and inferences drawn by applying descriptive statistics. Gender was coded as a binary variable (male and female). The education qualification was categorized into three groups (MBBS, MD/MS/Diploma/DNB, and DM/MCh). Type of work setting was categorised into two groups: Government and private organizations and level of setting was categorised into three groups: primary, secondary and tertiary care hospitals. Years of practice was categorized into four groups: <5, 5-10, 11-20, >20 years. The geographical region of India was grouped into five zones: North, South, East (including North East), West, and Central. Logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine predictors of aggregate knowledge, attitude and practices score among study participants. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical Consideration

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Post Graduate Institute of Medical Sciences (PGIMS), Rohtak, India (BREC/22/22 dated 19.04.2022). An online informed consent was obtained from all the participants at the start of the survey. Only those who provided the informed consent were taken to the questionnaire web page to initiate the survey. Steps were taken to ensure confidentiality and privacy of the information provided by the participants, and only de-identified data were used.

RESULTS

Out of total 710 physicians contacted from five geographical zones of India, 544 responded (non-response rate of 23.8%) and hence, 544 responses were included in analysis.

Demographic characteristics

Table 1 depicts the demographic profile of study participants. The mean age of the participants was 34.7 years and approximately 60 percent were males. The majority had postgraduate qualifications (364; 66.9%) and worked in government settings (79.4%). The respondents belonged to different levels of settings, the bulk being tertiary care (83.8%). It was observed that around 45% (244) and 27% (149) respondents had more than 5 and 10 years of experience, respectively.

Knowledge domain of the questionnaire

The mean (SD) score in knowledge domain was 8 (1.6) with majority of the participants having average (330; 60.7%) and good (208; 38.2%) scores. An overwhelmingly high proportion were of the opinion that indiscriminate use of antibiotics (534; 98.2%) and use of broad-spectrum agents (521; 95.8%) contributes to AMR. Limited access to essential antibiotics as a contributing factor to AMR emergence was believed by around half of the respondents (51%). More than 50% respondents were not familiar with WHO AWaRe classification of antibiotics. Although majority felt the importance of hospital antibiograms in guiding empiric antibiotic therapy (85.7%), yet it was not clear to more than 60% that antibiograms from different hospitals are usually dissimilar. Knowledge with respect to agent/s effective against anaerobes was not satisfactory with only 171 (31.5%) correct responses. There was variation among participants with respect to the understanding of different advantages of IV to oral switch of antibiotics. The pooled analysis of the knowledge domain of study questionnaire is summarized in table 2.

Attitude domain of the questionnaire

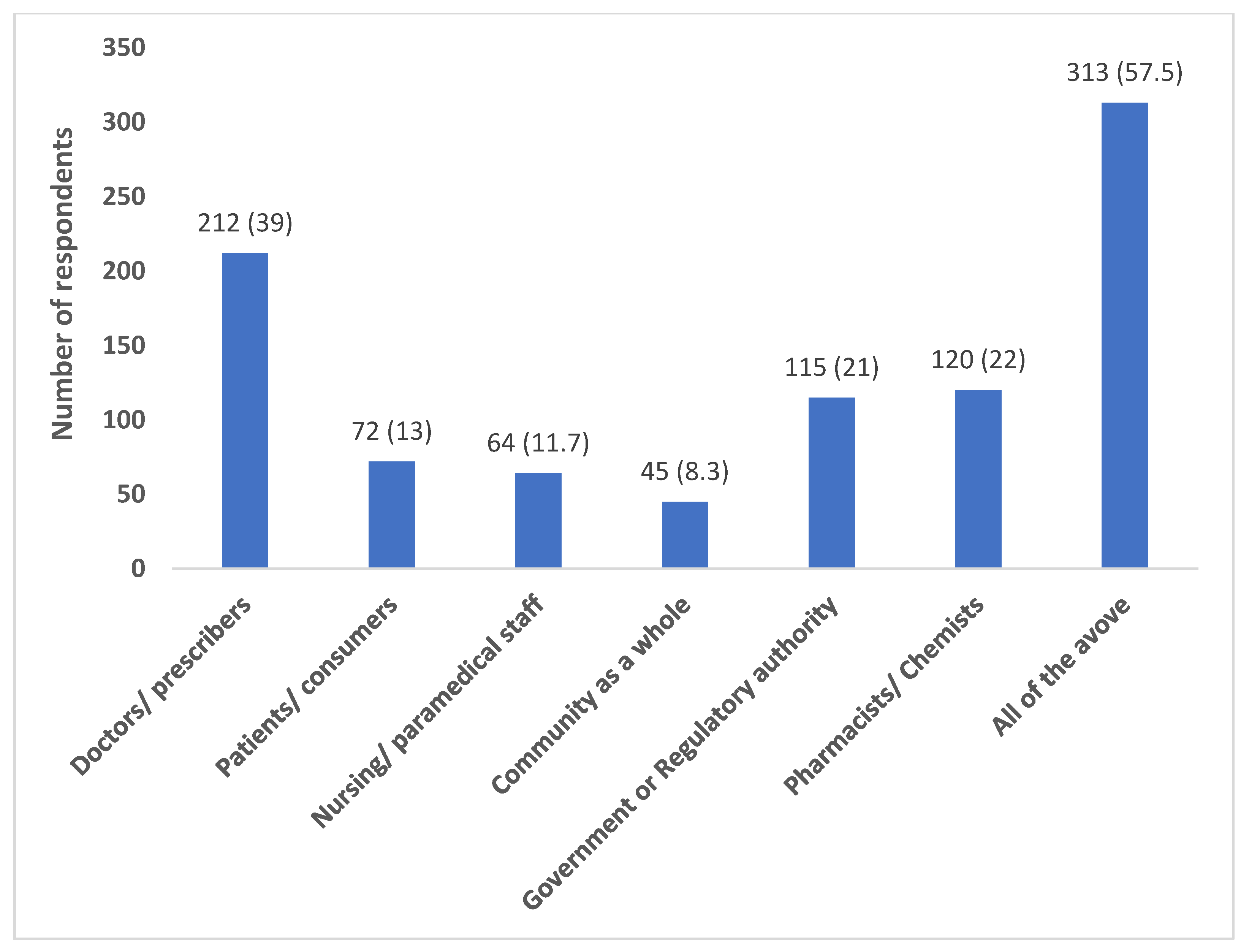

Most of the participants (418; 76.8%) believed that their antibiotic prescribing behaviour has an impact on the development of antibiotic resistance in their region. A relatively good proportion felt a combined role of all the stakeholders (doctors, patients, nurses, chemists, government, community) (313; 57.5%) in addressing the issue of antibiotic resistance (

Figure 1).

The perceptions of respondents regarding the strategies that can be helpful in handling the issue of AMR are represented in

Figure 2.

Table 3 illustrates the level of agreement among respondents in other antibiotic use practices. A relatively large number (478; 87.8%) agreed on the need of regular surveillance to combat AMR. Most of them disagreed on prescribing antibiotics on patients’

demands (488; 89.7%). Practices domain of the questionnaire

The item on factors determining the choice of antibiotics prescribed revealed that culture susceptibility report was the most common factor (78.3%) followed by local resistance patterns (48%), cost of antibiotics (41.5%), recommendations from seniors/ colleagues (27%) and own experience (26.6%) (

Figure 3).

Treatment guidelines (62.3%) were the most commonly reported source of information used while making decisions on antibiotic prescription followed by journals/ textbooks (47%), internet/social media (40.8%), conferences/ trainings/ CMEs (32.7%) and expert opinion (28.5%). 172 (31.6%) participants agreed on employing delayed/ back-up antibiotic prescribing in their clinical practice while 222 (40.8%) disagreed and 150 (27.6%) were not aware of the concept per se.

Table 4 details the respondents’ responses for other questions in practices domain.

203 (37.3%) participants had attended some trainings/ conferences to update their knowledge on antibiotic use during last 12 months.

Descriptive statistics of KAP scores

Table 5 summarizes the descriptive analysis of knowledge, attitude and practices score among healthcare professionals in India. Majority of the participants had good or average scores in all the three domains studied.

Predictors of aggregate KAP score

Table 6 depicts the results of logistic regression analysis of the predictors of aggregate KAP score among the participating physicians. Specialists/ super-specialists from basic and medicine/allied sciences were found to be associated with higher scores in comparison to non-specialists. Working in secondary healthcare setting was significantly associated with lower scores as compared to tertiary care. Physicians from central zone were found to have significantly higher aggregate scores. Other factors such as age, gender, years of practice and highest educational qualification were not found to have influence on aggregate KAP scores among participants.

DISCUSSION

The present cross-sectional survey was conducted with a viewpoint to evaluate the knowledge, attitudes, and practices in regard to antibiotic prescribing of physicians working in government as well as private settings across India with an ultimate goal of identifying knowledge gaps and inform interventions that could lead to judicious use of antimicrobials and help in containment of AMR.

Pooled analysis revealed that majority of the participants had postgraduate qualifications and worked in tertiary care government settings. The respondents largely opined that indiscriminate use of antibiotics and use of broad-spectrum agents lead to emergence of AMR, an observation in congruence with other similar surveys from India and other LMICs [17-19, 25-27]. Most of the participants (478/544; 87.8%) agreed on regular surveillance of antibiotic use and resistance at local, regional, national and global levels to combat AMR. Lack of access to essential antimicrobials leads to resorting to alternative agents which may be less efficacious, in turn promoting the emergence and spread of resistance among pathogens [

31], a fact which was though not appreciated by majority of participants. Also, many respondents were not familiar with WHO AWaRe (access, watch and reserve) classification; thereby highlighting the need to educate physicians about it and the fact that as per WHO recommendation, more than 60 percent of antibiotic use in hospitals should be from access group [

32]. Many studies conducted within and outside India have reported excess use of watch group of antibiotics in hospital and community settings; a serious concern contributing to AMR [33-37]. Increasing awareness among physicians and sensitising them towards favourable higher use of access compared to watch group of antibiotics is a crucial step towards optimal use of these agents. A relatively poor understanding regarding the concept of antibiograms was also evident in the study participants with only 38% correct responses regarding similarity of antibiograms for different hospitals thereby suggesting the need for trainings in this area as well.

Restricted use of double anaerobic cover and intravenous (IV) to oral switch of antibiotics are among the key strategies defined for successful implementation of antibiotic stewardship. We tried to identify the knowledge gaps, if any, pertaining to these concepts among study participants. Responses to the item on agent/s effective against anaerobes was quite dissatisfactory with around 70 percent respondents not being aware of anaerobic cover being provided by all the 3 agents (metronidazole, meropenem and amoxyclav) listed in the questionnaire; lack of knowledge in this area probably leads to use of double anaerobic cover by physicians as reported in literature [36-38]. Most of the respondents were not able to appreciate all the listed benefits of switching intravenous antibiotics to oral route when clinically desirable, a finding consistent with a survey in Nigeria where more than half of the participating physicians believed that parenteral antibiotics are more effective than the oral ones [

18].Specific recommendations to sensitize physicians on intravenous to oral switch of antibiotics and restricting the use of double anaerobic and gram negative cover of antibiotics may be stressed upon.

WHO gave the slogan ‘Fight antibiotic resistance-it’s in your hands’ in 2017 to emphasize the crucial role of hand hygiene in preventing AMR [

18]. Further, on 5

th May 2022, World hand hygiene day, WHO, under its campaign ‘‘Save lives: Clean your hands’, adopted the slogan ‘Unite for safety - clean your hands’ to prioritize hand hygiene improvement [

39]. Despite such measures at international level, there is still a wide knowledge gap regarding link between infection prevention and control (IPC) practices and AMR as observed in our survey where only 53.8% of the participants believed that infection control measures (such as hand hygiene, cohorting etc.) may help in handling the issue of AMR. In a similar earlier survey from India less than 50% respondents were reported to perceive inadequate hospital infection control as the cause of AMR [

40]. In a survey in Nigeria, however, 88.5% physicians reported following adequate hand hygiene practices [

19]. Our findings are consistent with some other international surveys reflecting physicians’ under-rating of the role of IPC measures including hand hygiene in preventing AMR [18, 41-43]. Hence, measures need to be taken to make physicians cognizant regarding importance of various IPC practices in reducing the transmission of AMR in hospital settings.

Shorter duration of antibiotic therapy is another strategy defined under antimicrobial stewardship interventions; the basis for such recommendation is that the presence of evidence that it is as efficacious as longer duration and offers the added advantages of lower incidence of adverse effects and emergence of AMR [44-48] However, findings from our survey with only 34.5% perceiving the importance of shorter duration of antibiotic therapy in limiting AMR call attention to conduct of regular trainings and CMEs for imparting updated knowledge regarding antibiotic prescribing to clinicians.

A relatively higher proportion of our study respondents (76.8%) believed that their prescribing practices may influence the development of AMR in their region compared to an earlier survey in a LMIC (50.3%) [

19]. A good proportion also agreed on reducing non-prescription sale of antibiotics and limiting their use to cases with confirmed bacterial infections as key measures to handle the issue of AMR. Majority of the clinicians reported culture susceptibility report (78.3%) as the top criteria for choosing an antibiotic followed by local resistance patterns (48%) and cost of antibiotics (41.5%). However, the proportion of respondents practising a change/ discontinuation of empiric therapy on the basis of culture sensitivity report was not quite significant reflecting dissonance between knowledge and practices. In contrast to an earlier survey conducted in West Bengal by Nair et al [

25], very few participants in our study (9/544;1.6%) depended on recommendations from pharmaceutical companies for making choice of antibiotics prescribed. Treatment guidelines (62.3%) were the most commonly reported source of information used by study participants while making decisions on antibiotic prescription, an observation in agreement with most of other similar surveys [

18,

19,

21,

25].

A sizeable portion of the respondents (392/544, 72%) preferred prescribing two or more class/es of antibiotics in combination over single agents. A deeper analysis of the type and rationality of antibiotic combinations prescribed is demanded which was however outside the scope of present study. Future studies may also be planned in this field to assess the problem of irrational prescribing, if any, of antibiotic combinations.

Participants belonging to basic and medicine and allied sciences had overall KAP scores higher than their surgical counterparts, a finding similar to an earlier survey in India [

40].Another cross-sectional study in north India reported significant correlation between physicians’ experience in years and their perceptions regarding the importance of hand hygiene and culture susceptibility report directed treatment of bacterial infection [

27]. A survey conducted in Jordan by Karasneh et al also reported significantly higher knowledge scores among physicians, specialists and those having more years of experience [

17]. Respondents from central zone, mostly belonging to medical disciplines, had significantly higher scores compared to those from other zones of the country, a finding which however fails to draw any conclusions due to very limited number of responses from this zone.

In the context of AMR and antibiotic prescribing practices, ours is the most comprehensive study involving physicians from all the zones of India, working in government as well as private settings, belonging to different specialities, with educational qualifications ranging from graduation to super-specialization and having wide range of clinical experience. Hence, our results are more generalizable than earlier similar surveys from India [21,25-27,49-51].

The study had, however, several limitations due to resource constraints. The fact that we used convenience and snowball sampling approaches in the survey design must be taken into consideration while interpretation of results due to associated drawbacks such as selection bias and limited generalizability. In fact, majority of the respondents (83.8%) belonged to tertiary care hospitals and a very small proportion were from primary care hospitals (4.8%). Also, there were relatively unequal zone-wise participation rates with quite lesser representation from East and Central zones. Besides these concerns, shortcomings of self-reported data such as giving desirable answers rather than true practices undermining the credibility of results cannot be ignored. A useful approach to eliminate such social desirability bias could have been cross-checking the responses with actual prescription practices which was however not feasible due to online nature of the survey. We focused on the KAP of clinicians paying no heed to informal healthcare providers who are not qualified medical doctors but dispense antibiotics as part of their regular practice. Being cross-sectional in nature, the survey though provided a snap shot of the views of participants, yet a follow up study on the same participants may provide insights on changes in their attitudes over time especially after implementation of various strategies suggested here. Given the extensive data from across the country, we believe the study adds value in understanding the knowledge gap regarding optimal use of antibiotics among clinicians across the country and may help inform future strategies to improve the antibiotic prescribing practices with the ultimate goal of fighting the battle against the global pandemic threat of AMR.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study findings have strengthened the case for regular conduct of continuing medical education and trainings of clinicians on various aspects related to antimicrobial resistance, surveillance and use. On the basis of knowledge gaps identified in our survey, few areas deserving attention are: antibiograms along with their interpretation and applicability in appropriate agent selection, WHO AWaRe classification of antibiotics, guideline based recommendations for optimal use of antibiotic agents and duration of antibiotic therapy, double anaerobic cover and double cover for gram negative infections, irrational antibiotic combinations, and intravenous to oral switch of antibiotics when clinically desirable. Besides these, there is a need to emphasize upon the crucial role of infection prevention and control measures including hand hygiene not only among healthcare professionals but community as a whole. Increasing awareness on AMR and sensitization and training of clinicians on various listed issues is a key strategy towards safe and rational use of antimicrobials and herald the menace of AMR at local, national as well as global levels.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of Pt. B.D. Sharma Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences, University of Health Sciences, Rohtak (No. BREC/22/22 dated 19.04.2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the 302 corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy concerns.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Antimicrobial resistance collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO’s first global report on antibiotic resistance reveals serious, worldwide threat to public health. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2014/amr-report/en/ (accessed on February 2022).

- Fomda, B.A. , Khan, A., Zahoor, D. NDM-1 (New Delhi metallo beta lactamase-1) producing Gram-negative bacilli: emergence and clinical implications. Indian. J. Med. Res. 2014, 140, 672–678. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Klein, E.Y., Van Boeckel, T.P., Martinez, E.M., et al. 2018. Global increase and geographic convergence in antibiotic consumption between 2000 and 2015. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 115: E3463–70. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance. 2015. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/193736. (accessed on December 2021).

- Tornimbene, B., Eremin, S., Escher, M., et al. 2018. WHO global antimicrobial resistance surveillance system early implementation 2016-17. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 18(3):241–242. [CrossRef]

- Laxminarayan, R., Duse, A., Wattal, C., et al. 2013. Antibiotic resistance-the need for global solutions. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 13(12):1057–1098. [CrossRef]

- Seale, A.C., Gordon, N.C., Islam, J., et al. 2017. AMR surveillance in low and middle-income settings - a roadmap for participation in the global antimicrobial surveillance system (GLASS). Wellcome. Open. Res. 2:92. [CrossRef]

- Jinks, T., Lee, N., Sharland, M., et al. 2016. A time for action: antimicrobial resistance needs global response. Bull. World. Health. Organ. 94(8):558–558A. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. National Action Plan on AMR (NAP-AMR), 2017–2021. 2017. 2017. Available online: https://ncdc.gov.in/WriteReadData/l892s/File645.pdf (accessed on February 2022).

- Walia, K., Ohri, V.C., Madhumathi, J., et al. 2019. Policy document on antimicrobial stewardship practices in India. Indian. J. Med. Res. 149:180–184. [CrossRef]

- Chandy, S.J., Michael, J.S., Veeraraghavan, B., et al. ICMR programme on antibiotic stewardship, prevention of infection & control (ASPIC). Indian. J.Med. Res. 2014, 139, 226–230.

- Simões AS, Alves DA, Gregório J, Couto I, Dias S, Póvoa P, Viveiros M, Gonçalves L, Lapão LV. Fighting antibiotic resistance in Portuguese hospitals: Understanding antibiotic prescription behaviours to better design antibiotic stewardship programmes. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2018 Jun;13:226-230. [CrossRef]

- Gharbi M, Moore LS, Castro-Sánchez E, Spanoudaki E, Grady C, Holmes AH, et al. A needs assessment study for optimising prescribing practice in secondary care junior doctors: the Antibiotic Prescribing Education among Doctors (APED). BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):456. [CrossRef]

- Fleming A, Bradley C, Cullinan S, Byrne S. Antibiotic prescribing in long-term care facilities: a qualitative, multidisciplinary investigation. BMJ Open. 2014;4(11):e006442. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Gonzalez C, López-Vázquez P, Vázquez-Lago JM, Pineiro-Lamas M, Herdeiro MT, Arzamendi PC, et al. Effect of physicians’ attitudes and knowledge on the quality of antibiotic prescription: a cohort study. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0141820. [CrossRef]

- Karasneh RA, Al-Azzam SI, Ababneh M, Al-Azzeh O, Al-Batayneh OB, Muflih SM, Khasawneh M, Khassawneh AM, Khader YS, Conway BR, Aldeyab MA. Prescribers' Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviors on Antibiotics, Antibiotic Use and Antibiotic Resistance in Jordan. Antibiotics (Basel). 2021 Jul 15;10(7):858. [CrossRef]

- Ogoina D, Iliyasu G, Kwaghe V, Otu A, Akase IE, Adekanmbi O, Mahmood D, Iroezindu M, Aliyu S, Oyeyemi AS, Rotifa S, Adeiza MA, Unigwe US, Mmerem JI, Dayyab FM, Habib ZG, Otokpa D, Effa E, Habib AG. Predictors of antibiotic prescriptions: a knowledge, attitude and practice survey among physicians in tertiary hospitals in Nigeria. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2021 Apr 30;10(1):73. [CrossRef]

- Chukwu EE, Oladele DA, Enwuru CA, Gogwan PL, Abuh D, Audu RA, Ogunsola FT. Antimicrobial resistance awareness and antibiotic prescribing behavior among healthcare workers in Nigeria: a national survey. BMC Infect Dis. 2021 Jan 7;21(1):22. [CrossRef]

- Kamuhabwa, A.A.R.; Silumbe, R. Knowledge among drug dispensers and antimalarial drug prescribing practices in public health facilities in Dar EsSalaam. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2013, 5, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakolkaran, N.; Shetty, A.V.; NDRD’S; Shetty, A.K. Antibiotic prescribing knowledge, attitudes, and practice among physicians in teaching hospitals in South India. J Fam Med Prim Care. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2017, 6, 526–532. [CrossRef]

- Pearson M, Chandler C. Knowing antimicrobial resistance in practice: a multi-country qualitative study with human and animal healthcare professionals. Glob Health Action. 2019;12(sup1):1599560. [CrossRef]

- Laxminarayan, R.A.; Duse, C.; Wattal, A.K.; Zaidi, A.K.M.; Wertheim, H.F.L.; Sumpradit, N. Antibiotic resistance - the need for global solutions. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013, 13, 1057–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal UC, Gwee K-A, Holtmann G, et al. Physician Perceptions on the Use of Antibiotics and Probiotics in Adults: An International Survey in the Asia-Pacific Area. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021. 11:722700. [CrossRef]

- Nair, M.; Tripathi, S.; Mazumdar, S.; Mahajan, R.; Harshana, A.; Pereira, A. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to antibiotic use in Paschim Bardhaman District: A survey of healthcare providers in West Bengal, India. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupte, V.; Gogtay, J.; Mani, R.K. A Questionnaire-based Survey of Physician Perceptions of the Prevalence of Antimicrobial Resistance and Their Antibiotic Prescribing Patterns. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2018, 22, 491–497. [Google Scholar]

- Trikha, Sonia, et al. Antibiotic prescribing patterns and knowledge of antibiotic resistance amongst the doctors working at public health facilities of a state in northern India: A cross sectional study. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care 2020, 9, 3937. [CrossRef]

- Khan AKA, Banu G, Reshma KK. Antibiotic Resistance and Usage—A survey on the Knowledge, Attitude, Perceptions and Practices among the Medical Students of a Southern Indian Teaching Hospital. J ClnDiagn Res. 2013; 7(8): 1613. [CrossRef]

- Sample size for frequency in a population. Retrieved March 21, 2022, from https://www.openepi.com/SampleSize/SSPropor.htm. 21 March.

- Bloom, B.S. Taxonomy of educational objectives, handbook I: the cognitive domain; David McKay Co Inc.: New York, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Pulcini, C.; Mohrs, S.; Beovic, B. Forgotten antibiotics: a follow-up inventory study in Europe, the USA, Canada and Australia. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2017, 49, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AWaRe policy brief. Available at https://adoptaware.org/assets/pdf/aware_policy_brief.pdf (accessed June 2022). 20 June.

- Skosana, P.P., Schellack, N., Godman, B., et al. 2021. A point prevalence survey of antimicrobial utilisation patterns and quality indices amongst hospitals in South Africa; findings and implications. Expert. Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 19(10):1353-1366. [CrossRef]

- Saleem, Z., Hassali, M.A., Versporten, A., et al. 2019. A multicenter point prevalence survey of antibiotic use in Punjab, Pakistan: findings and implications. Expert. Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 17(4):285-293. [CrossRef]

- Kurdi, A., Hasan, A.J., Baker, K.I., et al. 2021. A multicentre point prevalence survey of hospital antibiotic prescribing and quality indices in the Kurdistan Regional Government of Northern Iraq: The need for urgent action. Expert. Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 19(6):805-814. [CrossRef]

- Panditrao, A., Shafiq, N., Chatterjee, S., et al. 2021. A multicentre point prevalence survey (PPS) of antimicrobial use amongst admitted patients in tertiary care centres in India. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 76:1094–1101. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K., Sengupta, S., Antony, R., et al. 2019. Variations in antibiotic use across India: multi-centre study through global point prevalence survey. J. Hosp. Infect. 103:280–283. [CrossRef]

- Najmi, A., Sadasivam, B., Jhaj, R., et al. 2019. A pilot point prevalence study of antimicrobial drugs in indoor patients of a teaching hospital in Central India. J. Family. Med. Prim. Care. 8:2212–2217. [CrossRef]

- Tartari, E., Kilpatrick, C., Allegranzi, B. et al. “Unite for safety – clean your hands”: the 5 May 2022 World Health Organization SAVE LIVES—Clean Your Hands campaign. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 11, 63 (2022). 5 May. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Hazra, A.; Chakraverty, R.; Shafiq, N.; Pathak, A.; Trivedi, N. Knowledge, attitude, and practice survey on antimicrobial use and resistance among Indian clinicians: A multicentric, cross-sectional study. Perspect Clin Res 2022, 13, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babatola AO, Fadare JO, Olatunya OS, et al. Addressing antimicrobial resistance in Nigerian hospitals: exploring physicians prescribing behavior, knowledge, and perception of antimicrobial resistance and stewardship programs. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2020:1–10. [CrossRef]

- Garba, M.A.; Giwa, F.; Abubakar, A.A. Knowledge of antibiotic resistance among healthcare workers in primary healthcare centers in Kaduna North local government area. Sub-Saharan Afr J Med. 2020, 5, 86. [Google Scholar]

- Pulcini, C.; Williams, F.; Molinari, N.; Davey, P.; Nathwani, D. Junior doctors’ knowledge and perceptions of antibiotic resistance and prescribing: a survey in France and Scotland. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011, 17, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royer, S.; DeMerle, K.M.; Dickson, R.P.; Prescott, H.C. Shorter Versus Longer Courses of Antibiotics for Infection in Hospitalized Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Hosp Med 2018, 13, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneman, N.; Rishu, A.H.; Pinto, R. 7 versus 14 days of antibiotic treatment for critically ill patients with bloodstream infection: a pilot randomized clinical trial. Trials 2018, 19, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, R.G.; Claridge, J.A.; Nathens, A.B. Trial of short-course antimicrobial therapy for intraabdominal infection. N Engl J Med 2015, 372, 1996–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneman, N.; Rishu, A.H.; Xiong, W. Duration of Antimicrobial Treatment for Bacteremia in Canadian Critically Ill Patients. Crit Care Med 2016, 44, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chotiprasitsakul, D.; Han, J.H.; Cosgrove, S.E. Comparing the Outcomes of Adults With Enterobacteriaceae Bacteremia Receiving Short-Course Versus Prolonged-Course Antibiotic Therapy in a Multicenter, Propensity Score-Matched Cohort. Clin Infect Dis 2018, 66, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampath, S.; Venoukichenane, V. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of antibiotics usage among Health care personnel in a Tertiary care hospital. Sch J Appl Med Sci. 2016, 4, 3294–3298. [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo, K.C.; Tamhankar, A.J.; Johansson, E.; Lundborg, C.S. Antibiotic use, resistance development and environmental factors: a qualitative study among healthcare professionals in Orissa, India. BMC Public Health. 2010, 10, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabha, T.S.; Nandini, T.; Manu, G.; Savka, M.K. Knowledge, attitude and practices of antibiotic usage among the medical undergraduates of a tertiary care teaching hospital: an observational cross-sectional study. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol. 2016, 5, 2432–2437. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).