Submitted:

30 August 2023

Posted:

01 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

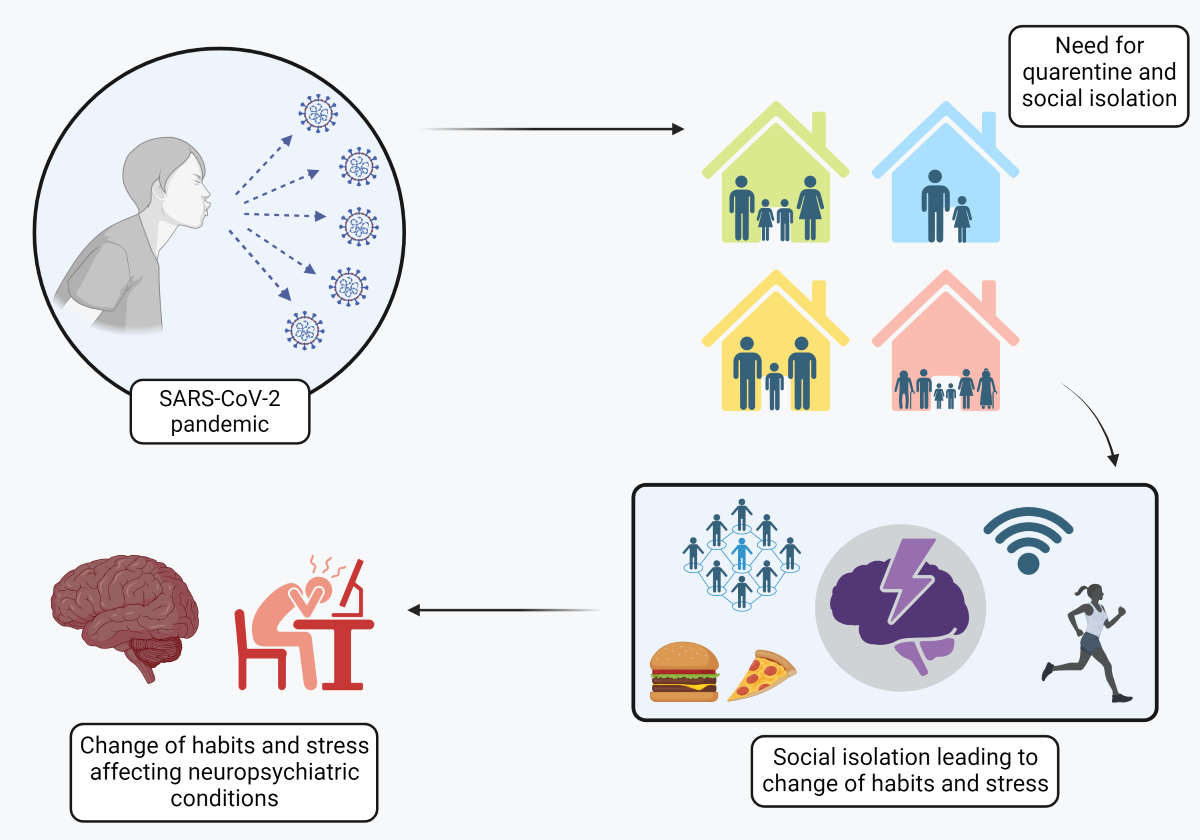

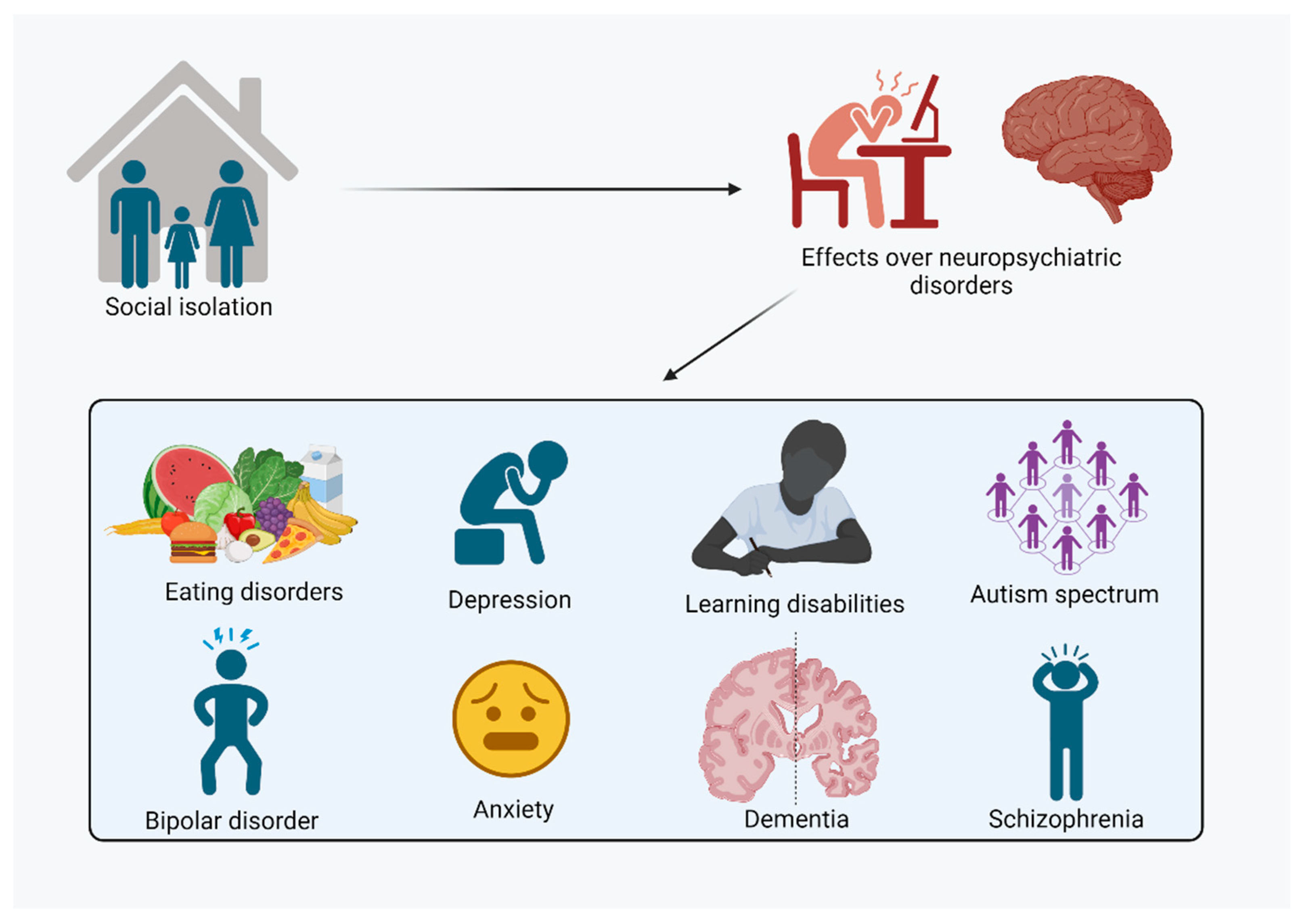

- The social isolation imposed by COVID-19 impacts the mental health of the world's population.

- The stress of social isolation exacerbated neuropsychiatric disorders.

- The stress generated by the Pandemic situation can trigger neuropsychiatric symptoms in vulnerable individuals.

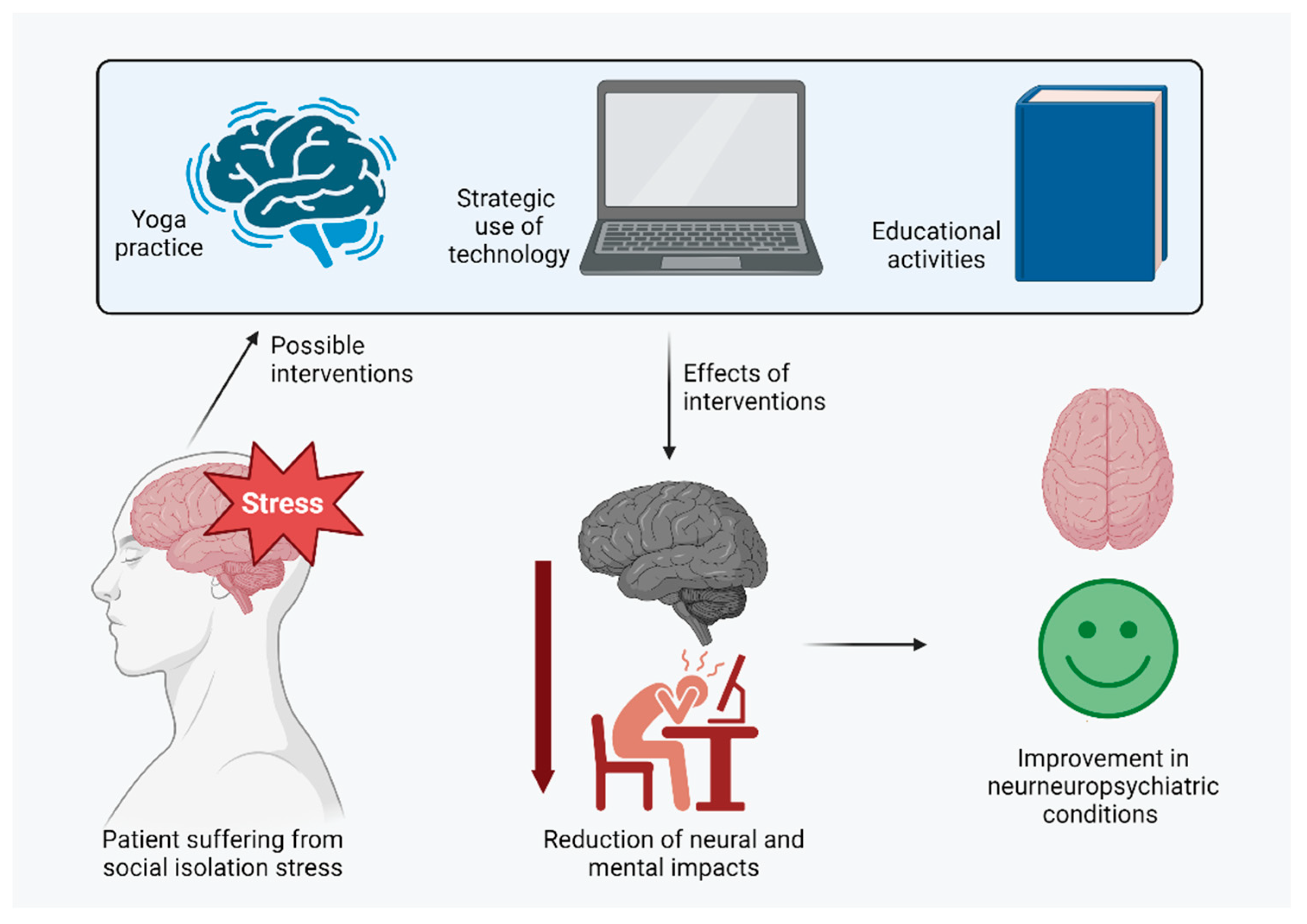

- Non-pharmacological therapeutic intervention strategies reduce the negative impacts on mental health.

1. Introduction

2. Impact of Social Isolation on Neuropsychiatric Disorders

2.1. Autism Spectrum Disorder

2.2. Learning Disabilities

2.3. Schizophrenia

2.4. Dementia

2.5. Depression and Anxiety

2.6. Bipolar Disorder

2.7. Eating Disorders

3. Strategies for Mitigating Neuropsychiatric Impairments

4. Considerations and Conclusions

References

- Banerjee, D.; Rai, M. Social Isolation in Covid-19: The Impact of Loneliness. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2020, 66, 525–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sepúlveda-Loyola, W.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, I.; Pérez-Rodríguez, P.; Ganz, F.; Torralba, R.; Oliveira, D.V.; Rodríguez-Mañas, L. Impact of Social Isolation Due to COVID-19 on Health in Older People: Mental and Physical Effects and Recommendations. J Nutr Health Aging 2020, 24, 938–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health and Well-Being . Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/major-themes/health-and-well-being#:~:text=The%20WHO%20constitution%20states%3A%20%22Health,of%20mental%20disorders%20or%20disabilities (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- Segre, M.; Ferraz, F.C. O Conceito de Saúde. Rev. Saúde Pública 1997, 31, 538–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, E.A.K.; Mitra, A.K.; Bhuiyan, A.R. Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health in Adolescents: A Systematic Review. IJERPH 2021, 18, 2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, R.A.L.; Improta-Caria, A.C.; Aras-Júnior, R.; de Oliveira, E.M.; Soci, Ú.P.R.; Cassilhas, R.C. Physical Exercise Effects on the Brain during COVID-19 Pandemic: Links between Mental and Cardiovascular Health. Neurol Sci 2021, 42, 1325–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socrates, A.; Mullins, N.; Gur, R.; Gur, R.; Stahl, E.; O’Reilly, P.; Reichenberg, A.; Jones, H.; Zammit, S.; Velthorst, E. Polygenic Risk of Social-Isolation and Its Influence on Social Behavior, Psychosis, Depression and Autism Spectrum Disorder; In Review, 2023.

- Xiong, Y.; Hong, H.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.Q. Social Isolation and the Brain: Effects and Mechanisms. Mol Psychiatry 2023, 28, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, R.; Catarino, S.; Miragaia, P.; Ferreras, C.; Viana, V.; Guardiano, M. Impacto de la COVID-19 en niños con trastorno del espectro autista. RevNeurol 2020, 71, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleffi, C.; Su, W.-C.; Srinivasan, S.; Bhat, A. Using Telehealth to Conduct Family-Centered, Movement Intervention Research in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pediatric Physical Therapy 2022, 34, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellicano, E.; Brett, S.; Den Houting, J.; Heyworth, M.; Magiati, I.; Steward, R.; Urbanowicz, A.; Stears, M. COVID-19, Social Isolation and the Mental Health of Autistic People and Their Families: A Qualitative Study. Autism 2022, 26, 914–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berruti, A.S.; Schaaf, R.C.; Jones, E.A.; Ridgway, E.; Dumont, R.L.; Leiby, B.; Sancimino, C.; Yi, M.; Molholm, S. Notes from an Epicenter: Navigating Behavioral Clinical Trials on Autism Spectrum Disorder amid the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Bronx. Trials 2022, 23, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; DSM-5-TR.; American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2022; ISBN 9780890425756.

- Alnahdi, G.H. The Interaction between Knowledge and Quality of Contact to Predict Saudi University Students’ Attitudes toward People with Intellectual Disability. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities 2021, 67, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christodoulou, J.A.; Cyr, A.; Murtagh, J.; Chang, P.; Lin, J.; Guarino, A.J.; Hook, P.; Gabrieli, J.D.E. Impact of Intensive Summer Reading Intervention for Children With Reading Disabilities and Difficulties in Early Elementary School. J Learn Disabil 2017, 50, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaywitz, S.E.; Shaywitz, B.A. Dyslexia (Specific Reading Disability). Biological Psychiatry 2005, 57, 1301–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruefach, T.; Reynolds, J.R. Social Isolation and Achievement of Students with Learning Disabilities. Social Science Research 2022, 104, 102667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haythorne, R.; Cruz, D.M.C.D.; Turner, H. Occupational Therapy Interventions for Adults with Learning Disabilities: Evaluating Referrals Received Pre and during the Height of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Cad. Bras. Ter. Ocup. 2022, 30, e3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, M.J.; Sawa, A.; Mortensen, P.B. Schizophrenia. The Lancet 2016, 388, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Hua, T.; Zeng, K.; Zhong, B.; Wang, G.; Liu, X. Influence of Social Isolation Caused by Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) on the Psychological Characteristics of Hospitalized Schizophrenia Patients: A Case-Control Study. Transl Psychiatry 2020, 10, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dementia. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- Kuiper, J.S.; Zuidersma, M.; Oude Voshaar, R.C.; Zuidema, S.U.; Van Den Heuvel, E.R.; Stolk, R.P.; Smidt, N. Social Relationships and Risk of Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Cohort Studies. Ageing Research Reviews 2015, 22, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holwerda, T.J.; Deeg, D.J.H.; Beekman, A.T.F.; Van Tilburg, T.G.; Stek, M.L.; Jonker, C.; Schoevers, R.A. Feelings of Loneliness, but Not Social Isolation, Predict Dementia Onset: Results from the Amsterdam Study of the Elderly (AMSTEL). Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2014, 85, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, C.R.; Scambler, S.J.; Bowling, A.; Bond, J. The Prevalence of, and Risk Factors for, Loneliness in Later Life: A Survey of Older People in Great Britain. Ageing and Society 2005, 25, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giebel, C.; Sutcliffe, C.; Verbeek, H.; Zabalegui, A.; Soto, M.; Hallberg, I.R.; Saks, K.; Renom-Guiteras, A.; Suhonen, R.; Challis, D. Depressive Symptomatology and Associated Factors in Dementia in Europe: Home Care versus Long-Term Care. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2016, 28, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giebel, C.; Cannon, J.; Hanna, K.; Butchard, S.; Eley, R.; Gaughan, A.; Komuravelli, A.; Shenton, J.; Callaghan, S.; Tetlow, H.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 Related Social Support Service Closures on People with Dementia and Unpaid Carers: A Qualitative Study. Aging & Mental Health 2021, 25, 1281–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchetti, A.; Rozzini, R.; Guerini, F.; Boffelli, S.; Ranieri, P.; Minelli, G.; Bianchetti, L.; Trabucchi, M. Clinical Presentation of COVID19 in Dementia Patients. J Nutr Health Aging 2020, 24, 560–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertollo, A.G.; Leite Galvan, A.C.; Dama Mingoti, M.E.; Dallagnol, C.; Ignácio, Z.M. Impact of COVID-19 on Anxiety and Depression - Biopsychosocial Factors. CNSNDDT 2024, 23, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Mental Health Report: Transforming Mental Health for All Available online:. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240049338 (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- Htun, Y.M.; Thiha, K.; Aung, A.; Aung, N.M.; Oo, T.W.; Win, P.S.; Sint, N.H.; Naing, K.M.; Min, A.K.; Tun, K.M.; et al. Assessment of Depressive Symptoms in Patients with COVID-19 during the Second Wave of Epidemic in Myanmar: A Cross-Sectional Single-Center Study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Nicola, M.; Dattoli, L.; Moccia, L.; Pepe, M.; Janiri, D.; Fiorillo, A.; Janiri, L.; Sani, G. Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Levels and Psychological Distress Symptoms in Patients with Affective Disorders during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2020, 122, 104869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalita, J.; Tripathi, A.; Dongre, N.; Misra, U.K. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic and Lockdown in a Cohort of Myasthenia Gravis Patients in India. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery 2021, 202, 106488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadur, C., U. B.; Pokharel, S.; Munikar, S.; Wagle, C.N.; Adhikary, P.; Shahi, B.B.; Thapa, C.; Bhandari, R.P.; Adhikari, B.; Thapa, K. Anxiety and Depression among People Living in Quarantine Centers during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Mixed Method Study from Western Nepal. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Li, Z.-X.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, X.-S.; Li, J.-J.; Wu, M.; Shi, G.-A.; Chen, R.-M.; Ji, X.; Zuo, S.-Y.; et al. [Effect of Shugan Tiaoshen acupuncture combined with western medication on depression-insomnia comorbidity due to COVID-19 quarantine: a multi-central randomized controlled trial]. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu 2023, 43, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraiss, J.T.; Ten Klooster, P.M.; Frye, E.; Kupka, R.W.; Bohlmeijer, E.T. Exploring Factors Associated with Personal Recovery in Bipolar Disorder. Psychol Psychother Theory Res Pract 2021, 94, 667–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B.; Baker, M.; Harris, T.; Stephenson, D. Loneliness and Social Isolation as Risk Factors for Mortality: A Meta-Analytic Review. Perspect Psychol Sci 2015, 10, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eidelman, P.; Gershon, A.; Kaplan, K.; McGlinchey, E.; Harvey, A.G. Social Support and Social Strain in Inter-Episode Bipolar Disorder. Bipolar Disord 2012, 14, 628–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, C.; Zhu, B.; Gou, D.; Tan, Z. An Acute Manic Episode During 2019-NCoV Quarantine. Journal of Affective Disorders 2020, 276, 623–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smink, F.R.E.; Van Hoeken, D.; Hoek, H.W. Epidemiology of Eating Disorders: Incidence, Prevalence and Mortality Rates. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2012, 14, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treasure, J.; Claudino, A.M.; Zucker, N. Eating Disorders. The Lancet 2010, 375, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, R.F.; Lombardo, C.; Cerolini, S.; Franko, D.L.; Omori, M.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M.; Linardon, J.; Courtet, P.; Guillaume, S. The Impact of the COVID -19 Pandemic on Eating Disorder Risk and Symptoms. Int J Eat Disord 2020, 53, 1166–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillipou, A.; Meyer, D.; Neill, E.; Tan, E.J.; Toh, W.L.; Van Rheenen, T.E.; Rossell, S.L. Eating and Exercise Behaviors in Eating Disorders and the General Population during the COVID -19 Pandemic in Australia: Initial Results from the COLLATE Project. Int J Eat Disord 2020, 53, 1158–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Termorshuizen, J.D.; Watson, H.J.; Thornton, L.M.; Borg, S.; Flatt, R.E.; MacDermod, C.M.; Harper, L.E.; Furth, E.F.; Peat, C.M.; Bulik, C.M. Early Impact of COVID -19 on Individuals with self-reported Eating Disorders: A Survey of ~1,000 Individuals in the United States and the Netherlands. Int J Eat Disord 2020, 53, 1780–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegl, S.; Maier, J.; Meule, A.; Voderholzer, U. Eating Disorders in Times of the COVID -19 Pandemic—Results from an Online Survey of Patients with Anorexia Nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 2020, 53, 1791–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi-Chi Chang, Y.; Wu, P.-L.; Chiou, W.-B. Thoughts of Social Distancing Experiences Affect Food Intake and Hypothetical Binge Eating: Implications for People in Home Quarantine during COVID-19. Social Science & Medicine 2021, 284, 114218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wade, T.D. The Impact of COVID -19 on Body-dissatisfied Female University Students. Int J Eat Disord 2021, 54, 1283–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giel, K.E.; Schurr, M.; Zipfel, S.; Junne, F.; Schag, K. Eating Behaviour and Symptom Trajectories in Patients with a History of Binge Eating Disorder during COVID-19 Pandemic. Eur Eat Disorders Rev 2021, 29, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhani, A.; Dehghani, M.; Gharraee, B.; Hakim Shooshtari, M. Parent Training Intervention for Autism Symptoms, Functional Emotional Development, and Parental Stress in Children with Autism Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Asian Journal of Psychiatry 2021, 62, 102735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikira, H.; Janković, S.; Slatina, M.S.; Muhić, M.; Sajun, S.; Priebe, S.; Džubur Kulenović, A. The Effectiveness of Volunteer Befriending for Improving the Quality of Life of Patients with Schizophrenia in Bosnia and Herzegovina – an Exploratory Randomised Controlled Trial. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2021, 30, e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buck, B.; Scherer, E.; Brian, R.; Wang, R.; Wang, W.; Campbell, A.; Choudhury, T.; Hauser, M.; Kane, J.M.; Ben-Zeev, D. Relationships between Smartphone Social Behavior and Relapse in Schizophrenia: A Preliminary Report. Schizophrenia Research 2019, 208, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, C.-A.; Yang, M.-H. Effect of Animal-Assisted Therapy (AAT) on Social Interaction and Quality of Life in Patients with Schizophrenia during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Experimental Study. Asian Nursing Research 2023, 17, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, T.; Barbarino, P.; Gauthier, S.; Brodaty, H.; Molinuevo, J.L.; Xie, H.; Sun, Y.; Yu, E.; Tang, Y.; et al. Dementia Care during COVID-19. The Lancet 2020, 395, 1190–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, D.S.; Bryan, C.J.; Gross, J.J.; Murray, J.S.; Krettek Cobb, D.; H. F. Santos, P.; Gravelding, H.; Johnson, M.; Jamieson, J.P. A Synergistic Mindsets Intervention Protects Adolescents from Stress. Nature 2022, 607, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Lin, D.; Goldberg, S.; Shen, Z.; Chen, P.; Qiao, S.; Brewer, J.; Loucks, E.; Operario, D. A Mindfulness-Based Mobile Health (MHealth) Intervention among Psychologically Distressed University Students in Quarantine during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Counseling Psychology 2022, 69, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Zhang, X.; Bai, S.; Minhat, H.S.; Nazan, A.I.N.M.; Feng, J.; Li, X.; Luo, G.; Zhang, X.; Feng, J.; et al. Assessing Social Support Impact on Depression, Anxiety, and Stress among Undergraduate Students in Shaanxi Province during the COVID-19 Pandemic of China. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabahang, R.; Aruguete, M.S.; McCutcheon, L. Video-Based Cognitive-Behavioral Intervention for COVID-19 Anxiety: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Trends Psychiatry Psychother 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbone, G.A.; Zarfati, A.; Nicoli, M.S.; Paulis, A.; Tourjansky, G.; Valenti, G.; Valenti, E.M.; Massullo, C.; Farina, B.; Imperatori, C. Online Psychological Counselling during Lockdown Reduces Anxiety Symptoms and Negative Affect: Insights from Italian Framework. Clin Psychology and Psychoth 2022, 29, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alawna, M.; Mohamed, A.A. An Integrated Intervention Combining Cognitive-behavioural Stress Management and Progressive Muscle Relaxation Improves Immune Biomarkers and Reduces COVID-19 Severity and Progression in Patients with COVID-19: A Randomized Control Trial. Stress and Health 2022, 38, 978–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latifian, M.; Raheb, G.; Abdi, K.; Alikhani, R.; Shariful Islam, S.M. The Effectiveness of Psychoeducation in Improving Attitudes towards Psychological Disorders and Internalized Stigma in the Family Members of Bipolar Patients: A Quasi-experimental Study. PsyCh Journal 2023, 12, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardi, V.; Meregalli, V.; Di Rosa, E.; Derrigo, R.; Faustini, C.; Keeler, J.L.; Favaro, A.; Treasure, J.; Lawrence, N. A Community-Based Feasibility Randomized Controlled Study to Test Food-Specific Inhibitory Control Training in People with Disinhibited Eating during COVID-19 in Italy. Eat Weight Disord 2022, 27, 2745–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juarascio, A.S.; Michael, M.L.; Srivastava, P.; Manasse, S.M.; Drexler, S.; Felonis, C.R. The Reward Re-Training Protocol: A Novel Intervention Approach Designed to Alter the Reward Imbalance Contributing to Binge Eating during COVID -19. Int J Eat Disord 2021, 54, 1316–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).