1. Introduction

Patients treated with opioids for cancer pain in palliative care outpatient clinics may be at high risk for non-medical opioid use (NMOU)[

1] and substance use disorder. NMOU[

2] refers to misuse of opioids to self-treat non-pain symptoms, concurrent use of illicit drugs, diversion to unintended users, and to varying degrees of opioid use disorder. NMOU is associated with a number of negative outcomes for patients and others in the community, including increased morbidity, opioid-related overdose death, and involvement in illegal activities.[

3] Substance use disorders have been associated with social instability,[

4,

5] poor symptom control,[

6] and may potentially contribute to poor patient adherence to cancer treatments. Cancer patients with substance use disorders have two potentially fatal and disabling conditions, both of which require the attention of clinicians.[

7,

8,

9] It is necessary to effectively screen for substance use disorder and monitor opioid use in palliative care clinics in order to ensure early identification and management of such complications.

Prescribers of opioids have long been required by federal and state law to use caution and ensure that the medications are prescribed and used appropriately. This includes careful screening and monitoring of patients at risk for NMOU, as well as timely identification of those who are actively engaging in NMOU behaviors and substance misuse.[

10,

11] Urine drug testing for drugs of abuse, and for the presence or absence of the prescribed opioids, is a risk assessment measure often employed in the treatment of chronic cancer and non-cancer pain.[

12,

13] There are two types of urine drug test (UDT) commonly employed for this purpose, the immunoassay test, and the more expensive, specific, and sensitive mass spectrometry methods which may be used for initial screening or to confirm a positive result on the UDT. Due to the expense of mass spectrometry testing, it may not be affordable in resource-limited clinics. It takes a longer time to get the results of the mass spectrometry testing and clinical treatment decisions may have to rely on the UDT in some circumstances.

A majority of studies on urine drug testing have reported on the use of mass spectrometry; few studies have examined how the use of immunoassay UDT could inform clinical practice. This paper reports on the results of a study of immunoassay UDT conducted in an ambulatory palliative medicine clinic located in a resource-limited safety-net county hospital caring for predominantly indigent and uninsured patients. The objective of this study was to examine the frequency of UDT abnormalities found with the immunoassay test. We also examined the patient characteristics and factors associated with the UDT results that were considered aberrant findings by the clinical team.

2. Materials and Methods

Study participants and procedure

We conducted a retrospective review of the electronic medical records of consecutive eligible patients seen at the outpatient palliative medicine clinic at Lyndon B. Johnson General Hospital (LBJ) in Houston, Texas between September 1, 2015 and December 31, 2020. LBJ is a safety-net hospital that serves predominantly low income and

uninsured patients. Approximately 85% of them are either uninsured or underinsured. A significant proportion of its revenue is generated from Medicaid Supplemental Programs. In Fiscal Year 2021, it provided over

$720 million in charity care.[

14] Patients were eligible for the study if they were 18 years of age or older, had a diagnosis of cancer (with or without active disease), and were receiving opioids for cancer related pain at any time during the study period. The study was approved by the institutional review board of UTHealth and Harris Health Systems.

Data collection

Patients’ baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were obtained within the first three clinic visits. These included: patient age; sex; race, ethnicity; marital status; cancer type; and cancer stage. Also obtained within the first three clinic visits were pertinent risk factors for nonmedical opioid use such as: history of illicit drug use; history of tobacco use; history of alcohol use; history of depression; history of bipolar disorder; history of schizophrenia; family history of illicit drug use; personal history of criminal activity (other than marijuana use); and contact with persons involved in criminal activity (other than marijuana use). Information regarding their opioid intake at the time of urine testing was obtained to assist with determining the morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD) and facilitating interpretation of the UDT results. Weekly meetings were held among the clinician investigators to ensure uniformity in the data collection process

Clinic process and instruments

As part of the standard procedure in the clinic, patients receiving chronic opioid therapy were screened using risk assessment questions and the state prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) database. Prior to opioid initiation, clinicians were encouraged to ask patients to complete a written pain treatment agreement and provide a verbal consent. Patients perceived to be at high risk for NMOU based on the risk assessment tools and clinical interviews were monitored more closely on an ongoing basis including close observation of certain behavioral patterns suggestive of NMOU. Clinicians were encouraged and reminded to routinely obtain a baseline UDT within the first three clinic visits on every patient receiving opioids. If the clinician believed that the patient was at elevated risk of NMOU, risk mitigation measures were implemented such as: increasing the frequency of visits to the clinic; more cautious and limited opioid prescription; more frequent urine drug testing; intensive counselling; and referral to psychology and psychiatry as available.

The Urine Drug Test

The specific UDT reagents used in this study were manufactured by either Siemens Vista or Beckman Coulter. These were immunoassay tests designed to screen for the presence of opiates, amphetamine, cocaine, phencyclidine, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and cannabinoids. The UDT is based on the reaction of the drug being tested for (analyte) with a reagent that binds to it. The binding reagents may react with other substances in the urine besides the analyte, causing there to be false positive test results. This may happen when the reagent used to detect the presence of benzodiazepines registers a positive result when the patient consumes, for instance, sertraline instead of benzodiazepines. The other substances in the urine which cause false positive results on the UDT may vary by the manufacturer of the reagent used for the test.[

15] The reagent used to detect opiates will bind to morphine or codeine but may fail to bind to synthetic or semi-synthetic opioids, because of their differences in chemical structure. Because of the potential for false positive results, or failure to detect substances consumed, confirmatory testing with mass spectrometry is often used along with the immunoassay UDT. Confirmatory testing was not available in this clinic during the study period, rendering the urine testing results presumptive and not conclusive, except for positive cocaine results which were considered conclusive.[

16] Because of the limitations of the type of UDT used, if a result indicated the consumption of an unauthorized or illicit substance, or a failure to detect a drug expected to be present, a review of the record and a conversation with the patient were used by the clinician to determine whether or not the UDT result reflected NMOU behavior. For this study, aberrant result in any part of the UDT caused that whole test to be counted as aberrant.

The prescribing clinicians consulted the literature which described the potential false positive or false negative results that may be encountered using the UDT.[

15,

17,

18] Consumption of methylphenidate, trazodone, labetalol, or over-the-counter cold preparations may all lead to a positive reading for amphetamine. If the UDT was positive for benzodiazepines, consumption of sertraline could lead to a false positive. If the UDT was positive for cannabinoids, the consumption of dronabinol, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or proton pump inhibitors might be the reason. A positive result on the UDT for phencyclidine might result from the consumption of dextromethorphan, diphenhydramine, or tramadol. If the UDT was positive for barbiturate, the use of primidone, ibuprofen, or naproxen could be the reason.[

17] However, the literature indicates that a positive result on the UDT for cocaine is reliably due to the consumption of cocaine, crack, coca leaf tea, or other cocaine containing products. Thus, when the UDT was positive for cocaine, the urine test was always deemed aberrant.

In order to minimize the impact on our interpretation of UDT results by potential patient dilution or substitution of samples submitted, a urinalysis, or a urine creatinine, was often ordered along with the UDT. A urine pH of 3 -11, a specific gravity of 1.002- 1.020, or a creatinine of ≥ 5 mg/dl indicate an unadulterated urine sample. Collection of the samples was not observed, so use of another person’s urine was also possible.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics such as frequency and percentage for categorical data, and median with inter-quartile range (IQR) for continuous variables, were used to summarize the results. Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test were used to assess the association between categorical variables and UDT findings. T-test was used to assess association between continuous variables and UDT findings. Univariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to explore the demographics and clinical factors associated with aberrant UDT findings. Aberrant UDT (yes, no) was the main outcome. The independent variables evaluated were age, sex (male, female), race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic other race, and Hispanic any race), marital status (married, single), cancer type (gastrointestinal, respiratory, gynecological, genitourinary, breast, head and neck, heme, and other), cancer stage (locally advanced, localized, recurrent, advanced, first line, and metastatic), history of illicit drug use (yes, no), history of marijuana use (yes, no), history of tobacco use (yes, no), history of alcohol use (yes, no), history of depression (yes, no), history of bipolar disorder (yes, no), history of schizophrenia (yes, no), family history of illicit drug use (yes, no), personal history of criminal activity (yes, no), and contact with persons involved in criminal activity (yes, no). P-value cut-off <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The data were analyzed with STATA software, version 17 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

Table 1 provides information on demographic and clinical characteristics of consecutive study patients seen at the palliative care clinic and those who underwent a baseline UDT within the first 3 clinic visits. Of 913 study patients seen in the clinic, 455 (50%) patients underwent a UDT within the first three visits and of those, 125 (27%) patients were found to have aberrant UDT results. The median age of patients seen in the clinic was 55 years. The majority were female (480, 53%), Hispanic, any race (425, 47%), and single (610, 67%). Half of the patients in the study did not get a UDT within the first three visits.

Abbreviations: UDT, urine drug test; NH, non-Hispanic; NMOU, nonmedical opioid use; MEDD, Morphine Equivalent Daily Dose (mg/day); IQR, interquartile range. aHomelessness and history of sexual abuse.

Table 2 shows the frequency and percentage of patients who were seen in the clinic, underwent the UDT, and had aberrant UDT results during the clinic visits. Overall, a majority (500, 55%) of patients seen in the clinic underwent at least one UDT during the entire study period. The UDT was most frequently administered during the initial visit. Of the patients who had a UDT, 91% had the test within the first three visits. Approximately 27% and 29% of the tests were deemed aberrant within the first three clinic visits and during the entire study period respectively. Aberrant results triggered a record review and conversation with the patient. None of the aberrant UDT results were caused by cross-reaction of prescribed or over-the-counter medications.

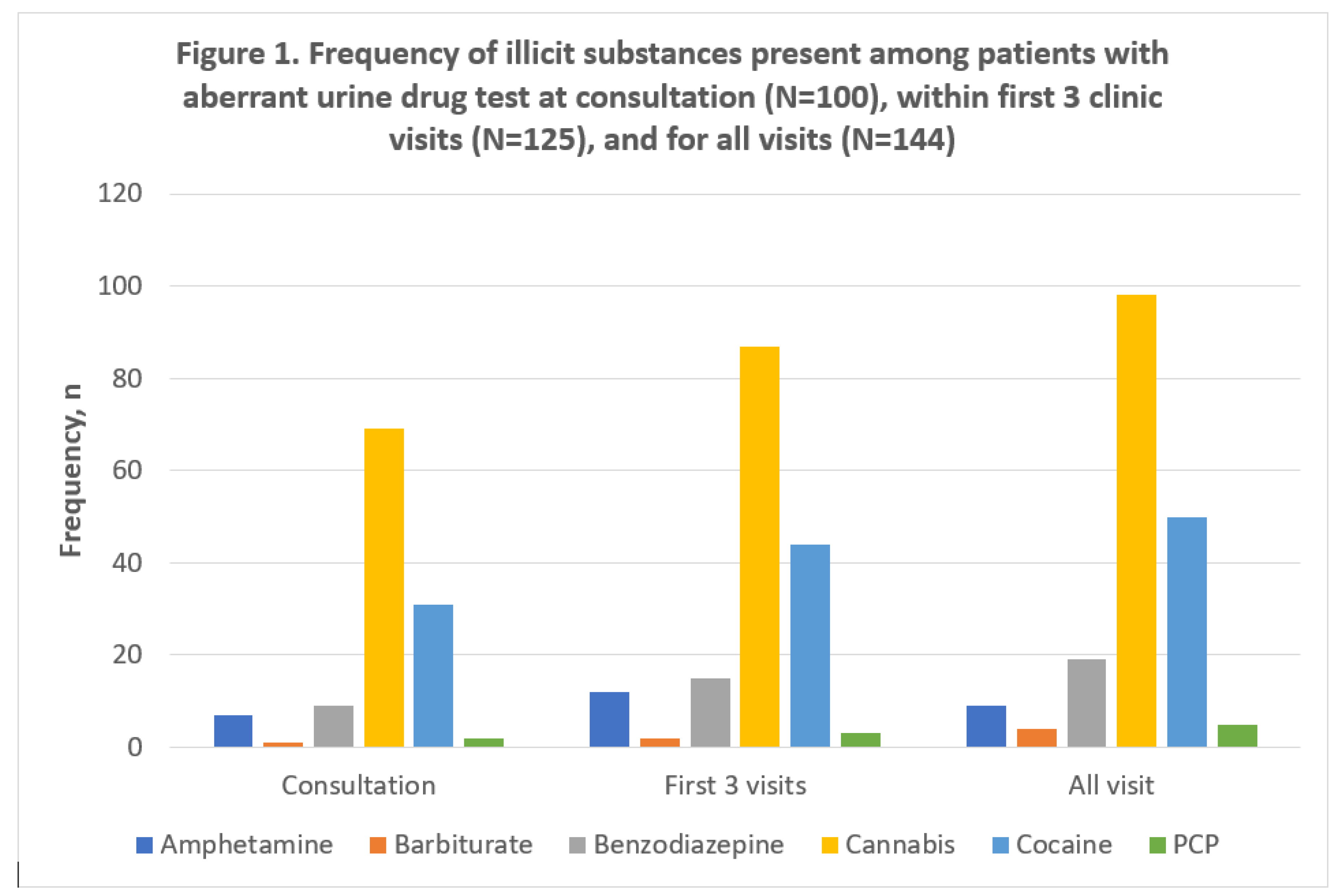

Figure 1.

depicts the types and distribution of illicit substances present in the UDT of the patients tested during the study period. Of the 125 patients who had aberrant urine samples in the first three clinic visits, the following numbers of patients had positive results for common illicit drugs screened for: amphetamine (9, 7%); barbiturate (2, 2%); benzodiazepines (15, 12%); cannabinoids (87, 70%); cocaine (44, 35%); and PCP (3, 2%). The patients who had cocaine in the urine constituted 9.7% of all patients that had urine tested during the first three visits.

Figure 1.

depicts the types and distribution of illicit substances present in the UDT of the patients tested during the study period. Of the 125 patients who had aberrant urine samples in the first three clinic visits, the following numbers of patients had positive results for common illicit drugs screened for: amphetamine (9, 7%); barbiturate (2, 2%); benzodiazepines (15, 12%); cannabinoids (87, 70%); cocaine (44, 35%); and PCP (3, 2%). The patients who had cocaine in the urine constituted 9.7% of all patients that had urine tested during the first three visits.

In a multivariable analysis of factors associated with the ordering of UDT (

Table 3), the odds of ordering a UDT within the first three visits to the clinic decreased by 3% with each one-year increase in the age (OR: 0.97; 95% CI: 0.96, 0.99). The odds of ordering a UDT among non-Hispanic Whites was 2.02 times (95% CI: 1.37, 2.98), and among non-Hispanic Blacks was 1.86 times (95% CI: 1.30, 2.65) than that of the Hispanics. Moreover, patients with head and neck cancer had 2.18 (95% CI: 1.25, 3.79) times the odds of ordering a test than those with a gastrointestinal cancer. Patients with locally advanced cancer stage had 58% (OR: 1.58; 95% CI: 1.10, 2.25) higher the odds of undergoing a test as compared to those with metastatic cancer. Additionally, patients with a prior history of illicit drug use had 1.81 times (95% CI: 1.08, 3.04), and those with a history of marijuana use had 1.65 times (95% CI: 1.09, 2.50) the odds of undergoing UDT within the first three visits. Also, non-Hispanic Whites had about twice (OR: 2.13; 95% CI: 1.03, 4.38) the odds of aberrant results as compared to Hispanics.

4. Discussion

Half of the 913 patients with cancer pain included in this study underwent a UDT during the first three clinic visits; of these 125 (27%) had aberrant UDT results. Forty-four (35%) of these 125 patients had UDT results positive for cocaine. The number of patients found to have aberrant UDT results was high. Studies have found similar abnormal urine testing results in other palliative medicine clinics.[

2,

19] Overall, our study shows that patients with cancer and on opioids have a significant risk for NMOU that could be detected with immunoassay UDT in routine clinical practice.[

19,

20] Cancer patients, like the general population, may have pre-existing drug-related issues. This, coupled with the increased exposure to opioids for cancer pain management, increases the risk for NMOU. [

3,

21]

The rate of cocaine use in our population was higher than some other studies involving populations with different socioeconomic factors.[

22] In one study conducted at another palliative care clinic whose patients have a different demographic mix, with a high percentage of insured and racial majority patients, 8.2% of these patients who underwent risk based UDT testing had cocaine in the urine[

12] and only 1% of patients who were randomly selected for urine drugtesting irrespective of risk tested positive for cocaine.[

23] Our study was conducted in a safety-net palliative medicine clinic with predominantly ethnic and racial minorities where most of the patients were uninsured, underinsured, and had less resources. Of the 913 consecutive patients in our study, 47% were Hispanic any race, 28% were black non-Hispanic, and 3% were of other races non-Hispanic. A large proportion of patients were tested. The percentage of patients testing positive for cocaine in the urine was higher than the risk-based testing protocol in the study mentioned above and would most likely have been even higher in our clinic if the testing was only directed toward patients with a high perceived risk of NMOU.

The high number of patients testing positive for cocaine is significant because concurrent use of cocaine and opioids can result in increased morbidity and mortality. Since substance use of one drug is often accompanied by misuse of other substances[

24], cocaine use disorder might be indicative of problematic use of other substances as well as opioids. Cocaine is a highly addictive substance that can cause multiple serious health risks such as intravenous drug use-related infections, cognitive deficits, overdose deaths, as well as long term cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, and neurovascular complications.[

25,

26] More than 500,000 people sought medical attention in an emergency room (ER) for cocaine related complications in 2011, accounting for over 40% of all ER visits involving illicit drug use.[

26] These issues, coupled with the potential dangers of aberrant opioid use and complications from cancer and it’s treatment, pose significant problems for cancer patients with comorbid cocaine use disorder and NMOU. Early identification of patients who actively engage in cocaine use presents an opportunity for clinicians to take the necessary steps to avert potential harm to their patients and make the appropriate referrals of these patients to receive specialist care. This underscores the important role that immunoassay UDT might have in less resourced populations where more expensive urine drug tests might not be available. It has been found that patients with substance use disorders who are undergoing cancer therapies and cancer symptom management face more challenges and may have worse outcomes.[

7,

8,

27] Further studies are needed to investigate the impact of cocaine and other substance use disorders on the adherence and outcomes among patients undergoing anticancer therapies.

The immunoassay test, although limited, was useful in identifying a significant number of patients consuming illegal and unauthorized substances who required greater vigilance and assistance. The UDT along with a review of the patient record and a conversation with the patient, can be of value although the results of the UDT are said to be presumptive except when cocaine is detected. The findings support the notion that this type of UDT may be useful as a routine risk mitigation tool in patients with chronic cancer pain. Entities such as the Centers for Disease Control explicitly excluded cancer related chronic pain from their guidelines.[

28] However, it is becoming more evident from multiple studies that urine drug testing is useful in chronic cancer related pain. Also, universal screening of all patients for substance use disorder and NMOU with UDT in a palliative care clinic[

27] would possibly reduce the potential negative impact of selective UDT testing on the physician-patient relationship. The patient is likely to see it as part of the clinic’s routine policy and not feel targeted if the UDT was required of all patients. The immunoassay UDT is inexpensive enough to use on entire clinic populations. The 2019 Medicare Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule indicates that the reimbursement rate for a 9-panel immunoassay drug test is

$65 while a 1-7 panel confirmatory drug testing is

$114 and an 8-14 confirmatory panel definitive testing is

$157[

29].

Limitations

One limitation of this study was that the data was collected retrospectively, thereby limiting our ability to obtain detailed real time information during the sample collection process. Moreover, it was conducted at a single center so the results may not be generalized to other clinical settings with different patient populations. The UDT was not obtained on every patient prescribed opioid medications although clinicians were encouraged to obtain the UDT within the first three visits regardless of perceived risk of NMOU. It is possible that some patients were in effect selected to undergo the test based on their risk profile or the clinician’s suspicion of NMOU behavior, while others were tested regardless of perceived risk. This might have increased the potential for selection bias and is a common limitation in multiple UDT studies in palliative care settings.[

12,

30,

31,

32] Lastly, the UDT in this study utilized the immunoassay technique which has the potential for false positive results and is limited in the opioids it may detect. It was unable to detect compounds such as oxycodone and synthetic opioids such as fentanyl and methadone. Ordering physicians often had to make further investigations to determine the aberrancy of a result.

5. Conclusions

Among patients receiving opioids for cancer pain at an ambulatory safety-net palliative medicine clinic who underwent immunoassay UDT, 27% and 29% of them were deemed aberrant within the first three clinic visits and during the entire study period respectively. A significant number of them tested positive for cocaine. The findings suggest that the immunoassay UDT test might have a role in opioid therapy among patients seen in under-resourced clinical settings, especially when coupled with review of the patient record and a conversation with the patient. Further studies are needed to examine the clinical effectiveness and benefits of immunoassay UDT in different clinical settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.H., S.P., D.H.; methodology, J.M.H., S.P., D.H; software, J.M.H., S.P.; validation, J.M.H., J.A.A., S.P., L.M.T.N., D.H.; formal analysis, B.C., S.A., R.P.; investigation, J.M.H., S.P., L.M.T.N., N.S., N.W., G.S., S.W., R.P., C.F., P.S., S.O.; resources, J.M.H., S.P., L.M.T.N., D.H.; data curation, D.H., B.C., S.A., R.P.; writing—original draft preparation, J.H., J.A.; writing—review and editing, J.M.H., J.A.A., S.P., L.M.T.N., D.H; visualization, J.M.H., J.A.A., S.P., L.M.T.N., D.H.; supervision, J.M.H., J.A.A., S.P., L.M.T.N., D.H; project administration, J.M.H., S.P., L.M.T.N., D.H; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

D.H. was supported in part by grants from the National Cancer Institute (R01CA214960; R01CA225701; R01CA231471).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas Health Science Center Houston. Harris Health System protocol code: HSC-MS-20-0725. eProtocol Number: 20-03-2304, dates of approval: 17 August 2020 and 9 September 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived by IRB. This was a retrospective chart review study. Information accessed: complete medical record. PHI that was retained: patient name, medical record number, date of birth. Data Availability Statement: The data presented in the study are available on request from the corresponding author, SP. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research subjects.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Childers, J.W.; King, L.A.; Arnold, R.M. Chronic Pain and Risk Factors for Opioid Misuse in a Palliative Care Clinic. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2015, 32, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barclay, J.S.; Owens, J.E.; Blackhall, L.J. Screening for substance abuse risk in cancer patients using the Opioid Risk Tool and urine drug screen. Support Care Cancer 2014, 22, 1883–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, T.D.; Rogak, L.J.; Passik, S.D. Substance abuse in cancer pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2010, 14, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swedo, E.A.; Sumner, S.A.; de Fijter, S.; Werhan, L.; Norris, K.; Beauregard, J.L.; Montgomery, M.P.; Rose, E.B.; Hillis, S.D.; Massetti, G.M. Adolescent Opioid Misuse Attributable to Adverse Childhood Experiences. J Pediatr 2020, 224, 102–109e103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merrick, M.T.; Ford, D.C.; Haegerich, T.M.; Simon, T. Adverse Childhood Experiences Increase Risk for Prescription Opioid Misuse. J Prim Prev 2020, 41, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addiction, N.C.o. ; Substance Abuse. Controlled prescription drug abuse at epidemic level. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 2006, 20, 61–64. [Google Scholar]

- Compton, P.; Chang, Y.P. Substance Abuse and Addiction: Implications for Pain Management in Patients With Cancer

Clin J Oncol Nurs 2017, 21, 203-209. [CrossRef]

- Passik, S.D.; Theobald, D.E. Managing addiction in advanced cancer patients: why bother? J Pain Symptom Manage 2000, 19, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, R.; Guirguis-Younger, M. Illicit drug use as a challenge to the delivery of end-of-life care services to homeless persons: perceptions of health and social services professionals. Palliat Med 2012, 26, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Code of Federal Regulations, T. , Chapter II, Part 1306. Availabe online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-II/part-1306 (accessed on ). 3 January.

- Texas Administrative Code, T. , Part 9, Chapter 170 Availabe online: https://texreg.sos.state.tx.us/public/readtac$ext.ViewTAC?

- Arthur, J.A.; Edwards, T.; Lu, Z.; Reddy, S.; Hui, D.; Wu, J.; Liu, D.; Williams, J.L.; Bruera, E. Frequency, predictors, and outcomes of urine drug testing among patients with advanced cancer on chronic opioid therapy at an outpatient supportive care clinic. Cancer 2016, 122, 3732–3739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, J.A. Urine Drug Testing in Cancer Pain Management. Oncologist 2020, 25, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris Health System Facts and Figures. Availabe online: https://www.harrishealth.org/about-us-hh/who-we-are/Pages/statistics.aspx (accessed on anuary 13).

- Moeller, K.E.; Lee, K.C.; Kissack, J.C. Urine drug screening: practical guide for clinicians. Mayo Clin Proc 2008, 83, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argoff, C.E.; Alford, D.P.; Fudin, J.; Adler, J.A.; Bair, M.J.; Dart, R.C.; Gandolfi, R.; McCarberg, B.H.; Stanos, S.P.; Gudin, J.A. , et al. Rational Urine Drug Monitoring in Patients Receiving Opioids for Chronic Pain: Consensus Recommendations. Pain medicine 2018, 19, 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.P.; Bluth, M.H. Common Interferences in Drug Testing. Clin Lab Med 2016, 36, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Algren, D.A.; Christian, M.R. Buyer Beware: Pitfalls in Toxicology Laboratory Testing. Mo Med 2015, 112, 206–210. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis, L.R.; Morrow, G.R.; Fetting, J.; Penman, D.; Piasetsky, S.; Schmale, A.M.; Henrichs, M.; Carnicke, C.L., Jr. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among cancer patients. JAMA 1983, 249, 751–757. [Google Scholar]

- Passik, S.D.; Portenoy, R.K.; Ricketts, P.L. Substance abuse issues in cancer patients. Part 1: Prevalence and diagnosis. Oncology (Williston Park) 1998, 12, 517–521, 524. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Edlund, M.J.; Sullivan, M.; Steffick, D.; Harris, K.M.; Wells, K.B. Do users of regularly prescribed opioids have higher rates of substance use problems than nonusers? Pain Med 2007, 8, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauenzahn, S.; Sima, A.; Cassel, B.; Noreika, D.; Gomez, T.H.; Ryan, L.; Wolf, C.E.; Legakis, L.; Del Fabbro, E. Urine drug screen findings among ambulatory oncology patients in a supportive care clinic. Support Care Cancer 2017, 10.1007/s00520-017-3575-1. [CrossRef]

- Arthur, J.A.; Tang, M.; Lu, Z.; Hui, D.; Nguyen, K.; Rodriguez, E.M.; Edwards, T.; Yennurajalingam, S.; Dalal, S.; Dev, R. , et al. Random urine drug testing among patients receiving opioid therapy for cancer pain. Cancer 2021, 127, 968–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Compton, W.M.; Blanco, C.; Crane, E.; Lee, J.; Jones, C.M. Prescription Opioid Use, Misuse, and Use Disorders in U. S. Adults: 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Ann Intern Med 2017, 167, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quello, S.B.; Brady, K.T.; Sonne, S.C. Mood disorders and substance use disorder: a complex comorbidity. Sci Pract Perspect 2005, 3, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers, A.A. Cocaine Side Effects, Risks & Dangers of Use. Availabe online: https://americanaddictioncenters.org/cocaine-treatment/risks (accessed on ). 3 January.

- Chhatre, S.; Metzger, D.S.; Malkowicz, S.B.; Woody, G.; Jayadevappa, R. Substance use disorder and its effects on outcomes in men with advanced-stage prostate cancer. Cancer 2014, 120, 3338–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowell, D.; Haegerich, T.M.; Chou, R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain - United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016, 65, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Services, C.f.M.a.M. Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule. Availabe online: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ClinicalLabFeeSched/Clinical-Laboratory-Fee-Schedule-Files-Items/19CLABQ1.html?DLPage=1&DLEntries=10&DLSort=2&DLSortDir=descending (accessed on ). 30 August.

- Koyyalagunta, D.; Bruera, E.; Engle, M.P.; Driver, L.; Dong, W.; Demaree, C.; Novy, D.M. Compliance with Opioid Therapy: Distinguishing Clinical Characteristics and Demographics Among Patients with Cancer Pain. Pain Medicine 2017, 10.1093/pm/pnx178, pnx178-pnx178. [CrossRef]

- Childers, J.W.; King, L.A.; Arnold, R.M. Chronic Pain and Risk Factors for Opioid Misuse in a Palliative Care Clinic. The American journal of hospice & palliative care 2014, 10.1177/1049909114531445. [CrossRef]

- Arthur, J.; Childers, J.; Del Fabbro, E. Should Urine Drug Screen be Done Universally or Selectively in Palliative Care Patients on Opioids? J Pain Symptom Manage 2023, 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2023.06.033. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).