1. Introduction

The global coronavirus pandemic has put pressure on researchers to develop, test, and deploy antiviral medications. Apart from medicines that act directly on the viruses, immune-stimulating preparations also seem to be interesting in the context of treating and preventing viral infections. Numerous reports on the immunomodulatory and antiviral activity of preparations containing zinc and selenium show that supplementation with these micronutrients may be beneficial for both prevention and treatment of viral infections, including coronaviruses [

1]. Dietary multi-micronutrient supplements containing selenium up to 200 µg/day have potential as safe, inexpensive, and widely available adjuvant therapy in viral infections, e.g., Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and Influenza AVirus (IAV). They can also be used in case of coinfections by HIV and Mycobacterium tuberculosis to support the chemotherapy and to improve the quality of life [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

Zinc status, like selenium, is a critical factor that can influence antiviral immunity; zinc-deficient populations are often most at risk of acquiring viral infections such as HIV or hepatitis C virus [

7,

8].

The biological availability of zinc and selenium from the pharmaceutical preparations is limited by many factors, intrinsic and extrinsic to the host. For both micronutrients the bioavailability, tissue distribution, and toxicity strongly depend on the form ingested. In general, organic forms have a higher bioavailability and/or lower toxicity than inorganic species [

9,

10,

11]. While both elements, zinc and selenium play a well-documented role in cancer prevention (e.g., for prostate cancer) and adjuvant therapy in viral infections (e.g., HIV, IAV), their combined supplementation is often given as a recommended prophylactic agent [

12,

13].

An interesting hypothesis, verified by the researchers for several years is synergism of the immunomodulatory effect of selenium (probably also zinc) and polysaccharides - mostly β-glucans of natural origin. Several members of the Basidiomycota division, often referred to as the “medicinal mushrooms”, can produce immunomodulating substances, which are usually polysaccharides [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Fungal polysaccharides are used as a non-invasive form of cancer treatment due to their ability to induce a non-specific response of the immune system against cancer cells. Further, this capacity is also evident against viral and bacterial infections and inflammation [

18].

Lentinula edodes is among the most well-studied fungi capable of biosynthesis of the most active immunostimulatory polysaccharides (e.g., lentinan), used in several countries in the treatment of cancer, HIV, hepatitis and other diseases related to immunodeficiency. Further, fungi are unique in the accumulation of trace elements, which is a focus of interest of several research groups [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Thus, the submerged cultures of

Lentinula edodes have been used in our previous research to obtain new immunomodulatory preparations enriched in selenium. We assumed obtaining a synergistic effect of polysaccharide compounds and selenium, which was confirmed in the already published studies [

25,

26,

27].

In continuation, we have currently designed a new preparation containing immune-active polysaccharides and both selenium and zinc, two micronutrients necessary for the functioning of the immune system. The necessity to design a biotechnological process of cultivation the

L. edodes mycelial cultures enriched in Zn and Se has extended our interest in the interactions between selenite and zinc (II) ions in the substrate and their effects on the transport of these ions into the fungal cell. In fungi, the process of accumulation of ions from solutions consists of three phases: biosorption on the surface of the fungal cell wall, intracellular uptake, and chemical transformation [

28,

29]. For the examination of the last two processes, living fungal biomass is required. Culture media contaminated with heavy metals usually have a very complex composition, with the result that metals biosorption may be affected by the presence of other ions. Moreover, the mechanisms of intracellular uptake and chemical transformation differ for cations and anions. For zinc(II) ions and selenites, investigated in this work, the mechanisms of accumulation by the fungus are also diverse and in higher mushrooms remain poorly understood. An examination of the mechanisms of zinc(II) transport in Saccharomyces cerevisiae revealed the central role of the ZIP (Zrt-, Irt-like protein) family of zinc transporters [

30,

31]. Selenites in yeast were found to be absorbed in a metabolism-dependent way, using a transporter of phosphate or monocarboxylate [

32,

33,

34]. Gharieb and Gadd [

32] also reported a fast, metabolism-independent process during selenite uptake in S. cerevisiae. Carrier-mediated passive transport might be crucial to selenite absorption by

Flammulina velutipes [

35].

In our previous studies, we found that the introduction of selenites into the medium strongly affected heavy metal uptake in mycelia. Interestingly, the effect was variable for different ions. For Ni(II) and Fe(III) ions, the metal content in harvested mycelia rose in proportion to the selenite concentration in the culture medium. However, the Zn content in harvested mycelia decreased when the concentration of selenites in the medium rose [

24,

36]. Importantly, in our experiments, the molarities of Zn(II) and SeO

32- in medium were not high enough to precipitate ZnSeO

3 into the medium [

37]. Most likely the inhibition of zinc accumulation by selenites (and vice versa) resulted from the formation of soluble Zn(II)-selenite complexes in the culture medium. The phenomenon of Zn(II)-selenite complex compounds formation of different solubility, strength and charge, depending on the molar ratio of ions, has been described by Banks, Moriya and Sekine, Somer and Yilmaz and Feroci et al. [

38,

39,

40,

41]. Thus, determining the molar proportion of selenites and zinc (II) for the transport to the cell of both micronutrients has become an important task.

Considering all the factors described above, to obtain the new immunomodulatory preparation containing mushroom-derived polysaccharides, selenium and zinc we designed a multi-step approach:

in the first step, we have optimized the composition of the culture medium to obtain the L. edodes mycelia enriched in Se and Zn in the assumed concentrations,

then we have prepared mycelial extracts with defined polysaccharide, selenium and zinc content to test the expected biological activity,

in the last stage of the work, we determined the effects of L. edodes mycelium extracts with different proportions of selenium and zinc concentrations on human T cells activation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microorganism and cultivation media

The

Lentinula edodes (Berk.) Pegler strain used in this study was ATCC 48085. The seed culture was grown under conditions described in our previous works [

7].

2.1.1. Supplementation of media and growth conditions in mycelial shake-flask cultures

The culture media contained glucose at 5%, yeast extract at 1%, soybean extract at 1.5%, and KH

2PO

4 at 0.1% (w/v). The pH of the medium was 6.5. Mineral precursors (sodium selenite and/or zinc bromide) were added to the medium, as shown in

Table 1.

As a reference, we also performed a series of studies in which the cultivation medium was non-enriched. The zinc and selenium content in the unenriched medium were the control levels in these studies.

Mycelia were grown in shake-flask cultures in 500 mL flasks containing 200 mL of medium. The fermentation medium was inoculated with 5% (v/v) of the seed culture. Cultures were incubated at 26 °C in a rotary shaker (New Brunswick Scientific, Edison, NY) at 120 rev/min for 10 days. Mycelia were harvested by filtration, washed three times with redistilled water, and freeze-dried. All experiments were conducted for five times to ensure reproducibility.

2.1. Determination of selenium and zinc in L. edodes mycelium

The determinations were performed after microwave mineralization.

2.2.1. Microwave mineralization procedure

A microwave digestion procedure was performed using a closed-vessel microwave system (Magnum II, ERTEC). A total of 0.02 g of sample was placed in a Teflon container and digested with 3 mL of 65% HNO3 (Suprapur quality, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) in the microwave digestion system according to a four-stage program: 17-20 atm for 3 min (60% of the microwave power), 27-30 atm for 5 min (80 % of the microwave power), 42-45 atm for 8 min (100% of the microwave power), and cooling for 10 min. When cool, the sample was diluted to 25 mL with deionized water. If necessary, the solutions were diluted several times. A blank digest was prepared in parallel.

2.2.2. Determination of zinc content by high-performance ion chromatography (HPIC)

Chromatographic analyses were performed as described previously (6) on a Dionex DX-500 ion chromatograph (Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) equipped with an IP 25 isocratic pump, an IonPac CG 5A guard column, an IonPac CS 5A analytical column (250 x 4.6 mm I.D., 9 µm bead diameter, ethylvinylbenzene functionalized with both quaternary ammonium and sulfonate functional groups), a 25 μL injection loop, and a Dionex AD20 absorbance detector with a Pneumatic Controller (PC 10) post-column reactor. All samples were injected at least in triplicate. All measurements were made at 30 ± 1 °C. The eluent solution was 80 mM oxalic acid/100 mM tetramethylammonium hydroxide/50 mM potassium hydroxide at pH 4.7. The eluent flow rate was set to 0.3 mL/min. A solution of 4-(2-pyrridylazo)resorcinol (PAR) was used as the postcolumn reagent and its flow rate was set to 0.15 mL/min. The Dionex PeakNet chromatography workstation was used for instrument control and data acquisition.

2.2.3. Determination of the selenium content by reverse-phase high performance liquid chromatography (RPHPLC)

The reverse-phase high performance liquid chromatography method used for the determination of selenium was performed as described previously [

41]. Namely, a 0.1% solution of diaminonaphthalene (DAN) in 0.1 M HCl was prepared and stored in the dark at 4°C. The pH of each of digested sample dissolved in 8 mL of Suprapur water was adjusted to 1.8-2 by adding HCl or 7 M NH

3·H

2O, as needed. One milliliter of DAN was added to each sample and the mixtures were heated for 45 min at 75 °C. After cooling, 3 mL of cyclohexane was added, and the samples were shaken vigorously for 1 min to extract the fluorescent piazselenol. Prior to RP HPLC determination, the samples were stored in the dark. The sample solutions were diluted with cyclohexane as needed. A blank digest was manipulated similarly for use as a control. Selenium standard solutions (6.25-1000 ng Se/mL) were prepared under the same conditions. The fluorescence was a linear function of the concentration of Se in the tested range (correlation coefficient, R= 0.999). The RP HPLC conditions were as follows: eluent, acetonitrile: flow rate, 1.4 mL/min; temperature, 25 °C; injection volume, 20 μL. For fluorometric analysis, the excitation wavelength was 378 nm and emission wavelength were 557 nm. The piazselenol retention time was 3.1 min.

2.3. Determination of the selenium and zinc content in mycelial water extracts by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS)

The solvents and reagents used for the test had the highest purity class available on the market. Ultrapure water (18 MΩ cm-1 resistivity) was taken from the Barnstead NANOPURE DIAMON UV System and used to prepare all standards and sample solutions. Suprapur 65% HNO3 grade was used to dissolve the samples. A 10 µg/mL concentration multi-element solution was purchased from INORGANIC Ventures (Christiansburg, USA). The purity of the plasma gas (argon) and cell gas (helium) was greater than 99.999%.

Each sample was placed directly in the vessels sealed in the microdevice. 3 mL of HNO3 was added. The mineralization of the samples was carried out in a high-pressure laboratory microwave oven (Milestone UltraWAVE T640). The heating program was carried out in two steps: In the first step, the temperature was increased linearly from 25 to 210 °C in 15 minutes. In the second stage, the temperature was kept at 210 °C for 8 minutes. After mineralization, the samples were diluted with water to a final volume of 100 mL. The Zn (Se) sample was further diluted (5 mL - > 50 mL)

The quadrupole ICP-MS 7800 (Agilent Technologies, Japan) equipped with an eight-field collision chamber was used for element analysis. The internal standard (In) has been added to compensate for any effects of acids or instrument drift. Measurements were made with a nickel probe and skimmer cones. The ICP-MS operating conditions are summarized in

Table 2.

2.4. Preparation of the mycelial extracts

Hot water extracts were prepared from freeze-dried mycelium in a Soxhlet extractor. In order to investigate the effect of the micronutrient concentration ratio (zinc and selenium) on the immunomodulatory activity of the preparations, the following mycelial samples were selected for extraction:

mycelium cultured in medium not enriched with micronutrients (sample 0),

mycelium cultured in medium enriched only with selenium at a concentration of 0.8 mM (sample Se) ,

mycelium cultured in medium enriched only with zinc at a concentration of 0.8 mM (sample Zn),

mycelium cultured in medium enriched with selenium in a concentration of 0.8 mM and zinc in a concentration of 0.2 mM (sample Se/Zn),

mycelium enriched with selenium in a concentration of 0.2 mM and zinc in a concentration of 0.8 mM (sample Zn/Se).

After 8 hours of the extraction of 0.5 g of mycelium with 20 mL of water, the extract was evaporated under the reduced pressure. The freeze-dried extracts were used for tests of the chemical composition (polysaccharide, Zn and Se content) and redissolved in water to the appropriate concentration, for tests of biological activity.

2.5. Determination of the carbohydrate content in the mycelial extracts

The determination was performed by the phenol-sulphuric acid method (Dubois method) [

42].

One milliliter of the sample (water extract at a concentration of 0.3 mg/mL) was mixed with l mL of 5% phenol solution and 5 mL of concentrated H2SO4. The mixture was kept at room temperature for 10 minutes, and then heated at 30 °C for 20 minutes. Absorbance at 490 nm was measured. A calibration curve was constructed with different concentrations of 1:1 w/w galactose-mannose mixture (25-100 µg/mL) as the standard.

2.6. Determination of the effects of mycelial extracts on T cells activation

2.6.1. PBMCs isolation, culture and stimulation

Blood samples (8 mL) were collected from seven healthy donors. All blood samples were commercially obtained from the Regional Blood Centre in Warsaw. Isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) was performed by density gradient centrifugation on Histopaque-1077 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). PBMCs were collected at the interface of plasma and Histopaque, and washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The separated PBMCs were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) containing antibiotic-antimycotic solution (1.5% penicillin-streptomycin-amphotericin, Invitrogen, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) and 10% human serum (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) and counted. PBMCs (2 × 105 cells/well) were cultured in 96-well flat-bottom microplates (Nunc, Paris, France) as described in detail in our previous paper [

43]. Briefly, cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 Ab (coated on plate wells, 0,75 μg/mL, BD Pharmingen, USA) or Dynabeads™ Human T-Activator CD3/CD28 (2 μL per well, ratio 2:5, Gibco, MA, USA) and incubated with

L. edodes mycelium extracts at concentration of 100 µg/mL. PBMCs were cultured for 24 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator.

2.6.2. Flow cytometry

For flow cytometry 2 × 105 cells from each well were washed once in PBS and stained with antibodies against specific surface antigens (all from BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA): CD3-PerCP (SK7 clone), CD4-APC-Cy7 (SK3 clone), CD8-APC (SK1 clone), CD69- BV711 (FN50 clone, Horizon™), and CD25- FITC (2A3 clone). Prior to experiments each antibody was titrated in order to achieve highest signal to background ratio. Samples were incubated in the dark for 15 min in room temperature. Next, cells were rinsed in 1 mL of PBS without Ca2+ and Mg2+ with 0.01% sodium azide and resuspended in 60 μL PBS without Ca2+ and Mg2+ with 0.01% sodium azide. Cut off values for each positive population were based on fluorescence minus one experiment.

Relative frequencies of CD69 and CD25 expression were assessed on singlets populations of CD3+CD4+ T cells and CD3+CD8+ T cells. Flow cytometry was performed using a DxFLEX Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) and analyzed with CytExpert software.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses (biotechnological and analytical part) were performed using StatSoft, Inc. (2014) STATISTICA (data analysis software system), version 12. All computations were applied at a significance level of 0.05.

All data in groups were first tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. To compare the means of two groups, a t-test was applied if the variances of the two populations were equal, otherwise a Cochran-Cox test was applied. The check the homogeneity of variance, the Brown-Forsythe test was used.

Statistically significant differences between more than two groups were assessed using one-way analysis of variance preceded by checking the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance. For multiple comparisons, the Tukey post-hoc test was performed, while for comparing the control group to each of the others, Dunnett’s test was used.

Flow cytometry data was acquired and interpreted using CytExpert software (Beckman Coulter). Acquired data was then analyzed and visualized with GraphPad Prism 9.5.0 software. To determine normality of data sets Shapiro-Wilk and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests with α = 0.05, and each set was considered to have normal distribution when both tests had p > 0.05. To compare data sets repeated measures ANOVA test with Geisser-Greenhouse correction was made for data sets with normal distribution and Friedman tests for those without normal distributions, both with α = 0.05. Results were considered significantly important with p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Accumulation of Se and Zn in mycelium of L. edodes

3.1.1. Reference series and mycelial growth

The cultivation of the mushroom mycelium in medium non-enriched in Na2SeO3 and/or ZnBr2 afforded 7-8 g of dry weight of mycelium per liter of culture medium after 10 days. The selenium and zinc concentrations in the medium unenriched in sodium selenite and zinc bromide medium were 1.138 µM and 0.036 mM, respectively. The determination was performed after mineralization of a medium sample with concentrated nitric acid. The total Se and Zn contents were determined without speciation.

The selenium and zinc contents in the reference series of dried mycelium (mycelium cultivated in unenriched medium) equaled 1.27 and 289 µg/g, respectively. The mycelial growth in enriched media was only weakly affected by increasing the concentrations of the supplements.

A depressive effect was observed only in cultures enriched with sodium selenite or zinc bromide in concentrations higher than 0.4 mM. The mycelium growth significantly decreased when the second ion (selenite or zinc) was added to the medium (

Figure 1a,b), except for the cultures with a zinc(II)/selenite molar ratio of 1:1.

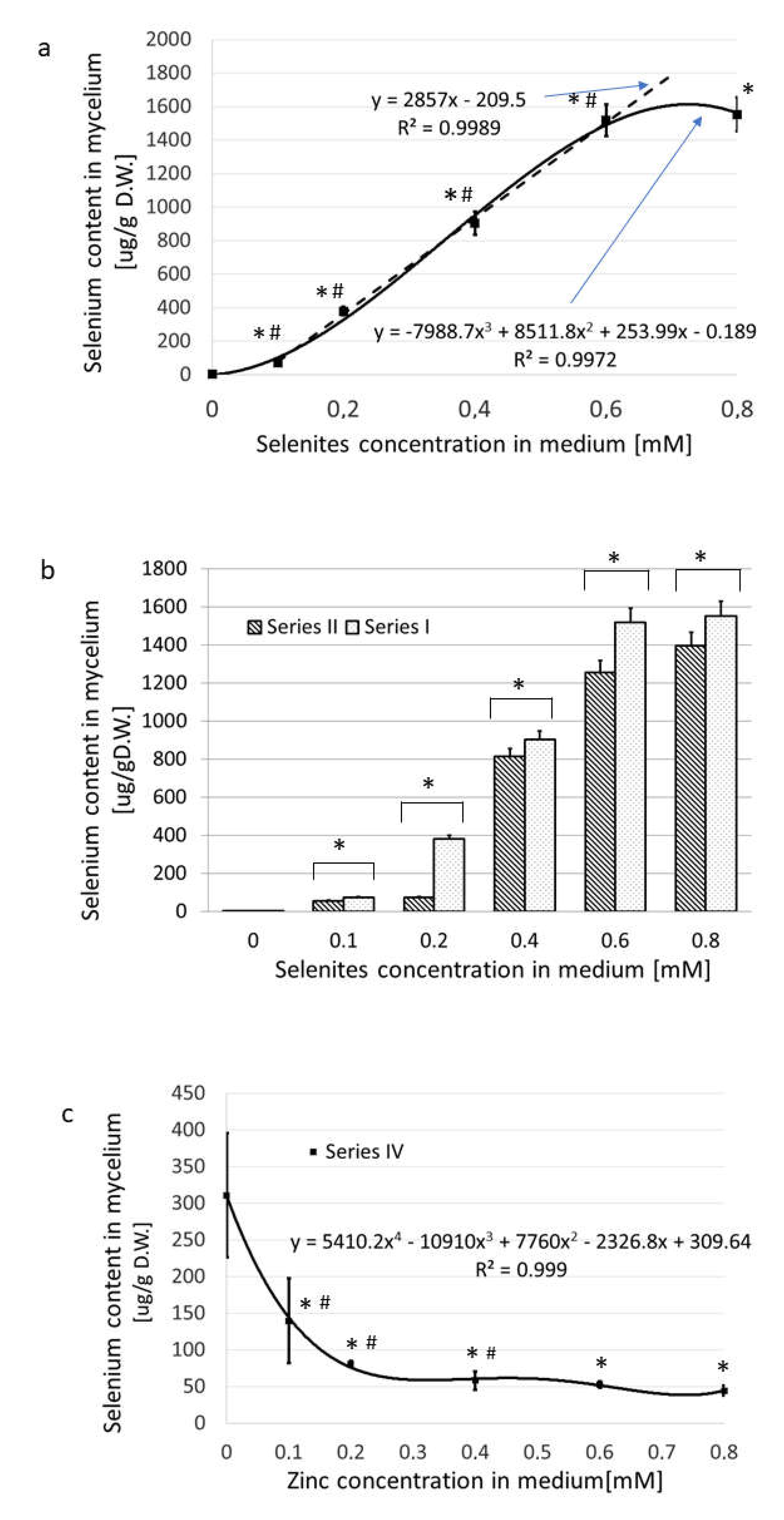

3.1.2. The accumulation of Se exclusively versus in the presence of Zn(II)

In the Series I (media supplemented with Na

2SeO

3), the uptake of selenium to the submerged cultivated mycelium was very effective, as it was found in our previous works [

45,

46]. Addition of 0.8 mmol/L of sodium selenite to the medium (the maximum concentration used) yielded 1554 µg of selenium per 1 g of mycelial dry weight (

Figure 2a,

Table S1).

The content of selenium in the mycelial dry weight correlated well with the Na

2SeO

3 concentration in the medium for concentrations ranging from 0.1-0.6 mM. At levels higher than 0.6 mM, no additional uptake of Se from the medium occurred (

Figure 2a).

In Series II (medium enriched in Na

2SeO

3 and containing zinc bromide at 0.2 mM), equimolar concentrations of zinc and selenites in the medium resulted in an 83% decrease (p < 0.05) in the selenium content in mycelium as compared with Series I (

Figure 2b). In the presence of an excess of selenites, the selenium absorption was almost as effective as in Series I (decrease by about 10%, p < 0.05) (

Figure 2b). Selenium absorption decreased when the medium contained a constant amount of selenite (0.2 mM) and that the concentration of zinc rose from zero to 0.8 mM (Series IV) (

Figure 2c). The values of selenium absorption dropped from 311 to 45, (86%, p < 0.05). The greatest decrease in the concentration of selenium in the mycelium (by 74%) was observed when the zinc concentrations in the culture medium were 0.1-0.2 mM, thus providing a selenite/zinc(II) molar ratios of 2:1 and 1:1, respectively. Further increases of the concentration of zinc up to 0.8 mM (affording a 4:1 ratio of selenite/zinc(II)) did not further reduce the selenium content (

Figure 2c).

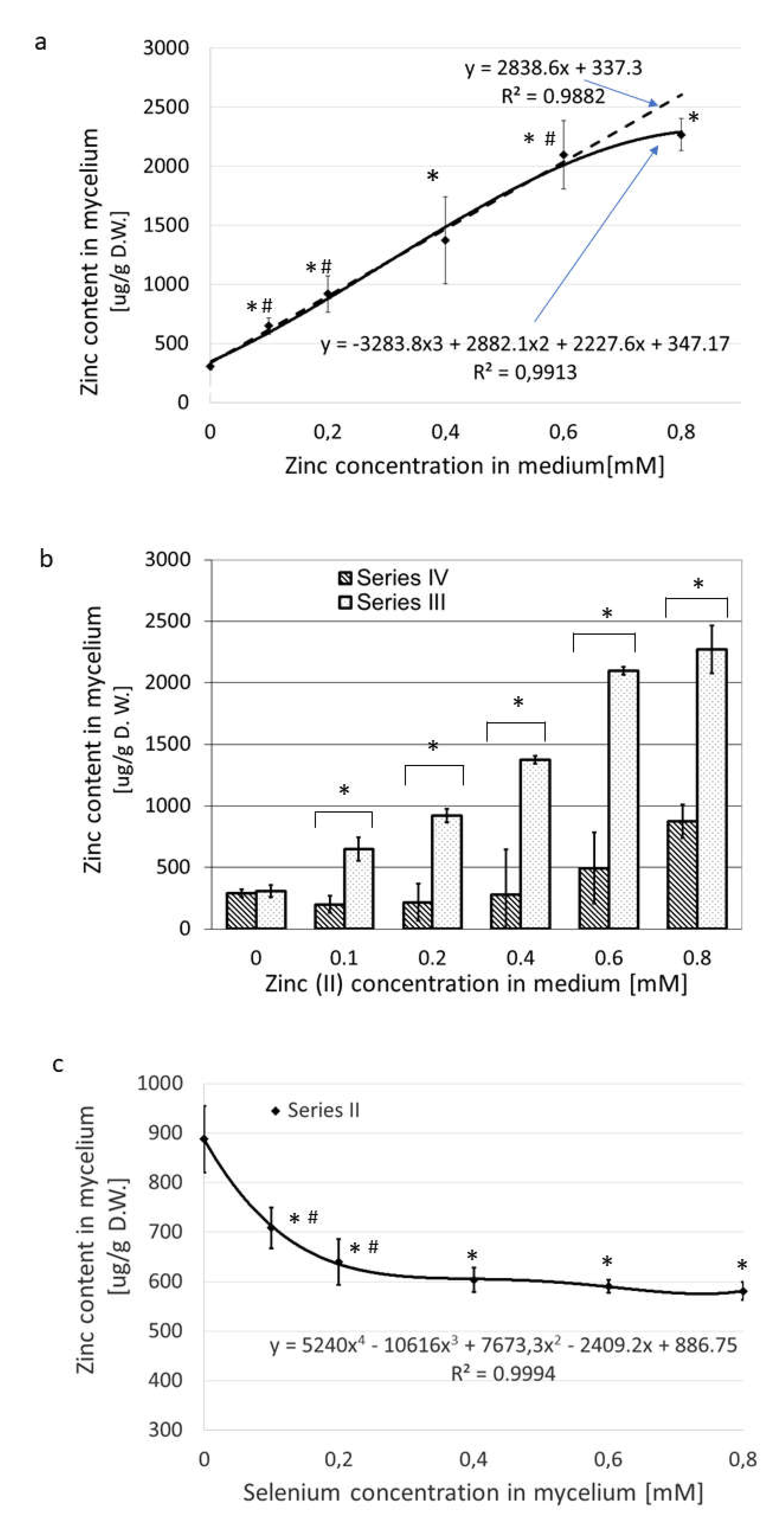

3.1.3. Zn(II) accumulation exclusively versus in the presence of SeO32-

Figure 3a and

Table S2 show the dynamics of zinc absorption when Zn alone was added to the medium in increasing concentrations (Series III). When the concentration of ZnBr

2 in the medium increased from nearly zero to 0.8 mM

, the values of absorbed zinc rose from 308 to 2370 µg/g dry weight. The content of zinc in the mycelium correlated well with its concentration in medium in the concentration range 0.1-0.6 mM (

Figure 3a).

The concentrations higher than 0.6 mM zinc bromide hampered Zn uptake from the medium. This effect was like that recorded for selenium uptake and suggests feedback inhibition at excessive concentrations, although another mechanism, such as saturation, may also be possible. When Na

2SeO

3 was held at a constant concentration of 0.2 mM in the medium and the ZnBr

2 concentration was increased over the range from nearly zero to 0.8 mM (Series IV), we noted an initial drop in the zinc absorption into the mycelium, but the change was not significant (

Figure 3b, series IV.) Under these conditions, as the Zn content of the medium increased, the absorbed level of Zn also increased by nearly three-fold in the medium supplemented with 0.8 mM ZnBr

2.

When the medium contained a fixed amount of zinc(II) (0.2 mM) and the concentration of selenium was varied from 0 to 0.8 mM (Series II), the values of absorbed zinc dropped from an initial high of 888 to as low as 591, approximately 25% (p < 0.05) (

Figure 3c). Under these experimental conditions, the greatest decrease in the concentration of zinc in the mycelium was observed with the lower selenium levels, 0.1 and 0.2 mM of selenites, in the culture medium, or with zinc(II)/selenite molar ratios of 2:1 and 1:1. Further increases in the concentration of selenium of up to 0.8 mM (four-fold excess relative to the concentration of zinc(II)) did not reduce the absorbed zinc content significantly (

Figure 3c).

3.2. Composition of the water extracts

Table 3. presents the data on the concentration of selenium, zinc and saccharides in the L. edodes mycelial hot water extracts. The results are given in comparison with the Zn and Se concentration in the extracted mycelia.

3.3. Immunological activity of mycelial extracts

Effective immune response to infection depends on the activation of immunocompetent cells [

47]. Activated T lymphocytes express on their surface numerous molecules, including CD69, and CD25 (also known as interleukin-2Rα) [

48]. CD69 is the earliest antigen upregulated four hours after activation. It is essential for T cell proliferation and survival. CD25 is upregulated 12–24 h after activation and initiates cells proliferation and differentiation [

49,

50,

51].

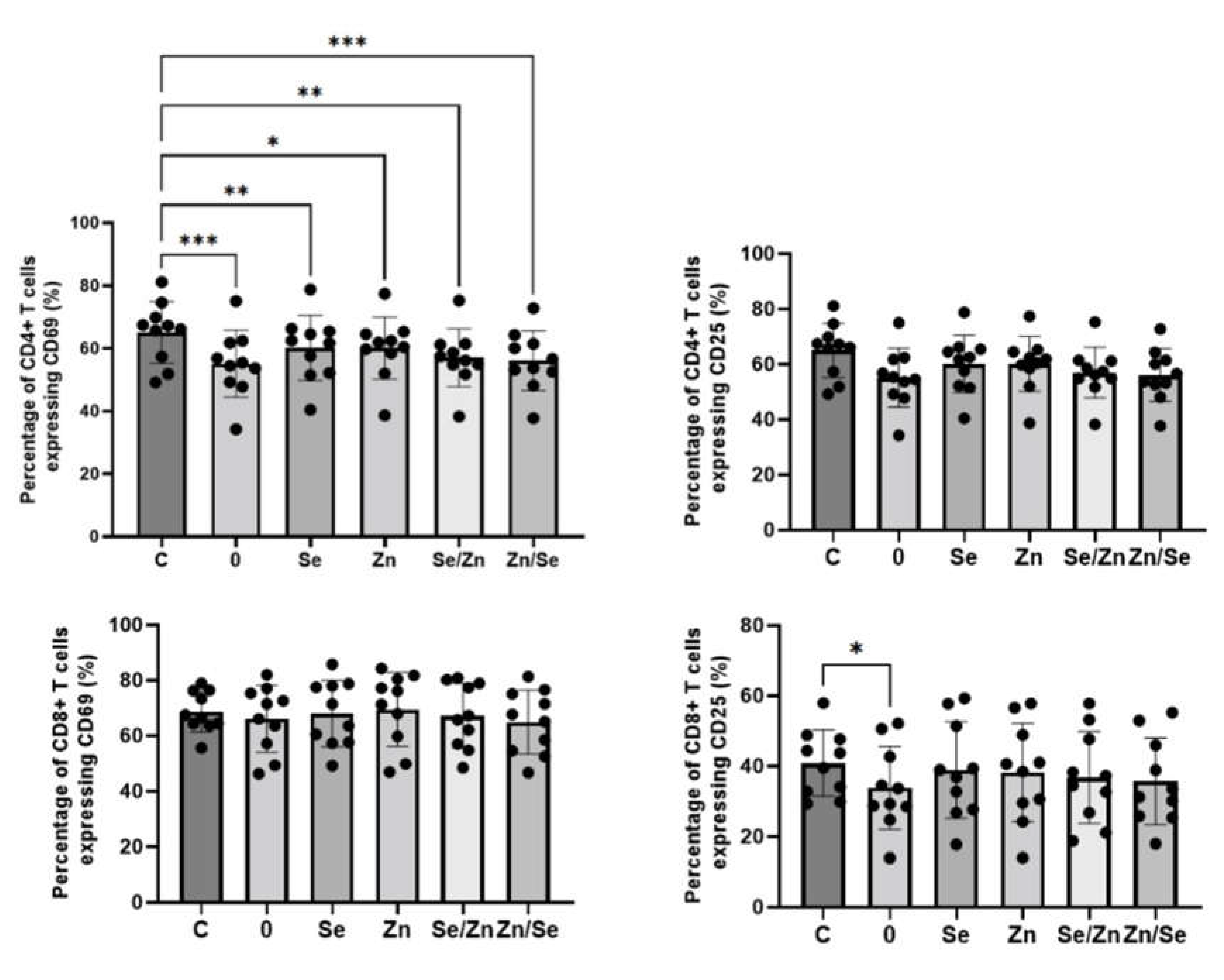

The effects of mycelial extracts on the expression of activation markers on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells stimulated with anti-CD3 Ab is presented in

Figure 4. All analyzed extracts significantly downregulated the percentage of CD4+CD69+ T cells, however, extract not enriched with micronutrients (sample 0) showed the strongest effect in comparison to control (C: 65.07 ± 9.83%; sample 0: 55.11 ± 10.68%, p = 0.0004; sample Se: 60.11 ± 10.39%, p = 0.0049; sample Zn: 60.10 ± 9.90, p = 0.0358; sample Se/Zn: 57.00 ± 9.19%, p = 0.0028; sample Zn/Se: 56.07 ± 9.53%, p = 0.0008). The statistically significant impact on CD25 expression on CD4+ T cells was not observed (p > 0.05), however, this marker tended to be downregulated by the non-enriched extract. All analyzed extracts did not affect the expression of CD69 marker on CD8+ T cells (p > 0.05), but non-enriched fraction significantly downregulated the percentage of CD8+CD25+ T cells (40.84 ± 9.36% vs. 33.90 ± 11.78%, p = 0.0406).

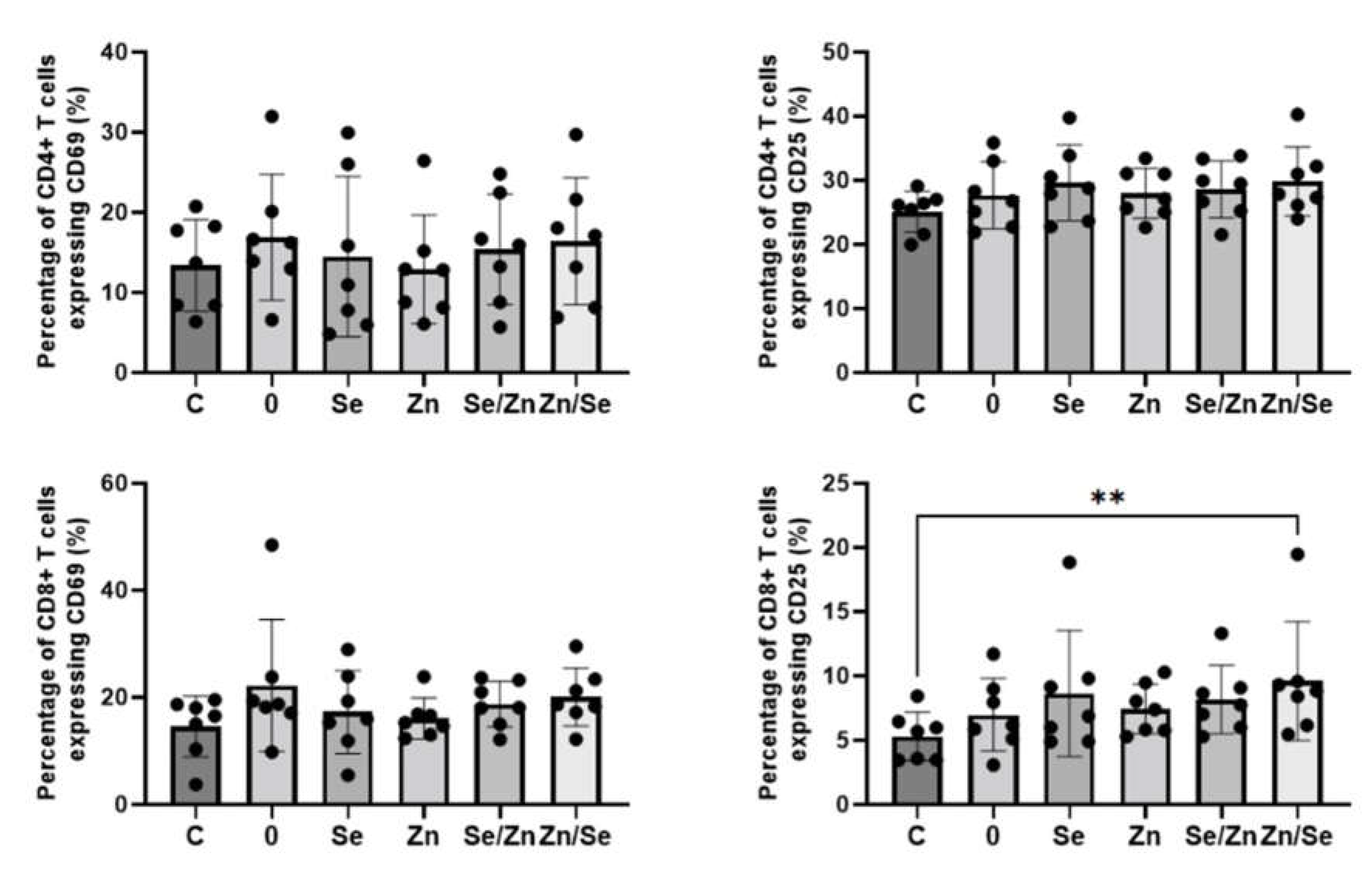

The effects of

L. edodes mycelial extracts on the expression of activation markers on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 Abs is presented in

Figure 5. When cells were stimulated with a dual signal, the number of CD4+ T cells expressing CD69, and CD25 marker was higher, however, the observed changes were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). All analyzed extracts showed no effects on the expression of CD69 marker o CD8+ T cells (p > 0.05), but extract enriched with Zn and Se (sample Zn/Se) significantly increased the number of CD8+CD25+ T cells (5.28 ± 1.89% vs. 9.60 ± 4.63%, p = 0.0017).

4. Discussion

As stated in the Introduction, the first objective of our study was to optimize the conditions for simultaneous accumulation of zinc and selenium in the mycelial cultures of

L. edodes, to obtain an immune-active preparation containing β-D-glucans and two micronutrients necessary for proper functioning of the immune system. The mutual blockade of the transport of selenium and zinc to animal and plant cells is a well-known phenomenon, although its mechanism is not entirely clear [

52]. Thus, we planned to check whether such a phenomenon, which could hinder the achievement of the assumed goal (obtaining a mycelium enriched in both, organic selenium, and zinc compounds) occurs in submerged cultured fungal cells.

As for the mutual influence of selenites and zinc(II) ions on the accumulation of Se and Zn in

L. edodes mycelial cultures: cumulation of selenium in the presence of zinc, and of zinc in the presence of selenium strongly decreased in comparison to amount the individual ion absorbed when the medium was supplemented with that ion alone (Fig.2. and Fig 3.). The mutual inhibitory effect of zinc ions and selenites on transport to the fungal cell is therefore like the effects described for other organisms [

52]. It turned out to be confusing, however, that the strongest indication comes from the results obtained at the Zn2+ to SeO

32- concentration ratio of 1:1 (0.2mM:0.2mM). Further, the substantial excess of the second ion did not cause a proportional inhibition of the accumulation process (Fig.2, Fig.3.). Since the molar ratio of ions in the culture medium influenced the accumulation of selenium and zinc in fungal cells more significantly than the absolute values of ion concentrations, we hypothesized that interactions between ions may be responsible for this phenomenon. We assumed that formation of the zinc-selenite complexes of different charges would very likely inhibit the first stage of the accumulation process, i.e., biosorption. This hypothesis was confirmed in our further research, however, due to the extensiveness of the material, it will be described in a separate publication.

Our previous studies have shown that the optimum concentration of sodium selenite in the cultivation medium, providing the

L. edodes mycelium enriched in organically bounded selenium was 0.12 - 0.25 mM (10-20 µg of Se/L) [

44,

45]. To provide the same selenium content in the mycelium when zinc (II) ions are present in the medium, the culture needs to be enriched in substantially higher amount of sodium selenite (above 0.4 mM). At this concentration of selenites, the strength of zinc ions should be lower than 0.4 mM to avoid the zinc selenite precipitation (the ion product would not exceed the solubility product of zinc selenite). Taking into consideration the strong inhibitory effect of equimolar concentrations of selenites and zinc(II) on accumulation of both elements, the zinc concentration of 0.2-0.3 mM should be considered optimum. However, the amount of Zn in the mycelium cultured under these conditions will be much lower than in cultures supplemented with zinc salts exclusively.

Further experiments were aimed at examining whether the enrichment of the

L. edodes preparations in selenium and zinc would give a stronger immunomodulatory effect than in each of these elements separately. Thus, for the preparation of the hot water extracts subjected to the immunological experiments, were selected mycelia enriched exclusively in selenium, exclusively in zinc and in both elements in two different proportions (

Table 3). The choice of the Zn(II) and SeO

32- concentration ratio in the culture medium (0.8:0, 0.8:0.2, 0.2:0.8, 0:0.8 mM) resulted from the data presented above (subsection 3.1.3.).

The results of the ICP-MS analysis showed that the concentrations of Se and Zn in the extracts were almost linearly dependent on their concentrations in the mycelium (

Table 3,

Figure 5). However, they were almost 1000 times higher in the extracts than in mycelium (mg/g versus µg/g ). To sum up: hot-water extractability of the derivatives of selenium and zinc from the

L. edodes mycelium was effective. Nevertheless, at high concentrations of Se and Zn in the mycelium the extractability of these elements clearly decreased. It's probably a consequence of binding to the structure of non-extractable proteins and polysaccharides.

The concentration of polysaccharides in the aqueous extracts clearly depended on the concentration of zinc and selenium in the mycelium. The highest concentration was in the extracts from the mycelium not supplemented with Se and/or Zn. Zinc supplementation had a much weaker effect on the concentration of polysaccharides in extracts than selenium supplementation. The lowest concentration of polysaccharides was found in extracts from mycelium supplemented with selenium alone. In our previous studies, we found that supplementation of cultures with high concentrations of selenium changed the structure of the fungal cell wall, significantly reducing the content of extractable polysaccharides. The current results confirm these findings.

The results obtained in immunological tests suggest that the highest biological activity possess

L. edodes water extracts not supplemented with Se or Zn (sample 0) or those where mycelium was enriched with Se concentration of 0.2 mM and Zn in a concentration of 0.8 mM (sample Zn/Se). Both analyzed T cells populations are essential in the protective immunity against viral infections, including SARS-CoV-2 [

53,

54] In our previous study we demonstrated that the direction of

L. edodes polysaccharides biological activity depends on the type of cells stimulation [

43]. The present study confirms these observations. When cells were stimulated only with anti-CD3 Ab, extracts decreased T cells activation. In contrast, when cells were stimulated with a dual signal (anti-CD3/CD28 Abs), which is more physiological [

55], extracts enhanced their activation. In conclusion, there is insufficient amount of evidence to confirm that Se or Zn supplementation to mycelial cultures of

L. edodes enhances the immunomodulatory properties of water extracts. Therefore, future studies on larger sample focusing on identification of intracellular signaling pathways are needed.

5. Conclusions

We have successfully optimized the composition of the culture medium to obtain the L. edodes mycelia enriched in Se and Zn in the assumed concentrations. The molar ratio of ions in the culture medium influenced the accumulation of selenium and zinc in fungal cells more significantly than the absolute values of ion concentrations. The obtained results indicate that interactions between selenate and zinc ions in the culture medium (complexation) influence the process of accumulation. This has an impact on the final concentration of microelements in biomass and in the designed dietary supplements.

In the mycelial preparations (water extracts) tested in the present study, the content of selenium and zinc was proportional to the content in the mycelium, although a significant part of Zn and Se was present in the mycelium in a form not water - extractable form (probably bound to proteins).

The immunoligical activity direction of the mycelial extracts strongly depends on the type of cells stimulation. More impotrtantly, the effect of the mycelial extracts containing polysaccharides as well as zinc and seleniumon the activation of T lymphocytes indicates the key role of fungal polysaccharides: the strongest effect was shown by preparations containing the highest concentration of these compounds, regardless of the presence of selenium and zinc. In case of preparations enriched in selenium and zinc, a significant predominance of the concentration of zinc over the concentration of selenium seems to be more advantageous. The selenium and zinc content in the examined preparations modified the immunomodulatory activity of mycelial polysaccharides, however, the mechanisms of action of various active ingredients of the mycelial extracts seem to be different.

In our opinion, however, there is insufficient amount of evidence to confirm that Se or Zn supplementation to mycelial cultures of L. edodes significantly enhances the immunomodulatory properties of water extracts. Therefore, future studies on larger sample focusing on identification of intracellular signaling pathways are needed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Ka., J.T.; methodology, M.Ka., J.T. (biotechnology), R.Z. and B.K. (immunology), A.B. (HPIC analysis), P.D. (ICP-MS analysis); A.R. (T cells activation experiments); validation, A.R., M.K., B.K.,; formal analysis, J.T.; investigation, M.Ka., E.D., A.B., M. Kr., S.G.-J., B.K, A.R., A.M.P., K.T., A.W.; resources, M.Ka.; data curation, M.Ka., E.M., B.K., A.R., M.Kl., A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Ka., J.T., B.K.; writing—review and editing, M. Ka., J.T., R.Z., B.K., M.Kr.; visualization, J.T., A.R., P.P. supervision, J.T.; project administration, J.T.; funding acquisition, S.G.-J, J.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grant FW26/N/19/20 and FW26/1/F/MBM/N/21 from the Medical University of Warsaw, Poland.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants provided consent to participate in the study. The study was approved by the local ethics committee.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author and co-authors.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank master’s students Magdalena Zielińska and Marzena Stachniak for their commitment to and help with part of the experimental work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jayawardena, R.; Sooriyaarachchi, P.; Chourdakis, M.; Jeewandara, C.; Ranasinghe, P. Enhancing Immunity in Viral Infections, with Special Emphasis on COVID-19: A Review. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baum, M.K.; Miguez-Burbano, M.J.; Campa, A.; Shor-Posner, G. Selenium and Interleukins in Persons Infected with Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1. J. Infect. Dis. 2000, 182, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, E.; Cox, A.; Zhao, L.; Ruzicka, J.; Bhat, A.; Zhang, W.; Nadimpalli, R.; Dean, R. Nutrition,HIV,and Drug Abuse:The Molecular Basis of a Unique Role for Selenium. J.Acquir Immune Defic. Syndr. 2000, 25, S53–S61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A.M.; Hu, Y.J.; Mansur, D.B. Glutathione Peroxidase and Viral Replication: Implications for Viral Evolution and Chemoprevention. Biofactors 2001, 14, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez, R.M.; Berría, M.I.; Levander, O.A. Host Selenium Status Selectively Influences Susceptibility to Experimental Viral Myocarditis. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2001, 80, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalkan, A.; Bulut, V.; Avci, S.; Celik, I.; Bingol, N.K. Trace Elements in Viral Hepatitis. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2002, 16, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraguchi, Y.; Sakurai, H.; Hussain, S.; Anner, B.M.; Hoshino, H. Inhibition of HIV-1 Infection by Zinc Group Metal Compounds. Antiviral Res. 1999, 43, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuasa, K.; Naganuma, A.; Sato, K.; Ikeda, M.; Kato, N.; Takagi, H.; Mori, M. Zinc Is a Negative Regulator of Hepatitis C Virus RNA Replication. Liver Int. 2006, 26, 1111–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano-Garcia, M. Organoselenium Compounds as Potential Therapeutic and Chemopreventive Agents: A Review. Curr. Med. Chem. 2004, 11, 1657–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Suzuki, N.; Ogra, Y. Bioavailability Comparison of Nine Bioselenocompounds in Vitro and in Vivo. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrauzer, G.N.; Surai, P.F. Selenium in Human and Animal Nutrition: Resolved and Unresolved Issues. A Partly Historical Treatise in Commemoration of the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Discovery of the Biological Essentiality of Selenium, Dedicated to the Memory of Klaus Schwarz (1914–1. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2009, 29, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daragó, A.; Sapota, A.; Nasiadek, M.; Klimczak, M.; Kilanowicz, A. The Effect of Zinc and Selenium Supplementation Mode on Their Bioavailability in the Rat Prostate. Should Administration Be Joint or Separate? Nutrients 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federico, A.; Iodice, P.; Federico, P.; Del Rio, A.; Mellone, M.C.; Catalano, G.; Federico, P. Effects of Selenium and Zinc Supplementation on Nutritional Status in Patients with Cancer of Digestive Tract. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 55, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.-T.; Wasser, S.P. The Role of Culinary-Medicinal Mushrooms on Human Welfare with a Pyramid Model for Human Health. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2012, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizuno, M.; Nishitani, Y. Immunomodulating Compounds in Basidiomycetes. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2013, 52, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasser, S.P. Current Findings, Future Trends, and Unsolved Problems in Studies of Medicinal Mushrooms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 89, 1323–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giavasis, I. Production of Microbial Polysaccharides for Use in Food. In Microbial Production of Food Ingredients, Enzymes and Nutraceuticals. In Microbial production of food ingredients, enzymes and nutraceuticals; Elsevier: Amsterdam,The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 413–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. Mushroom Polysaccharides: Chemistry and Antiobesity, Antidiabetes, Anticancer, and Antibiotic Properties in Cells, Rodents, and Humans. Foods 2016, 5, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pethkar, A. V.; Paknikar, K.M. Recovery of Gold from Solutions Using Cladosporium Cladosporioides Biomass Beads. J. Biotechnol. 1998, 63, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borovička, J.; Řanda, Z. Distribution of Iron, Cobalt, Zinc and Selenium in Macrofungi. Mycol. Prog. 2007, 6, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, M.C.S.; Naozuka, J.; Da Luz, J.M.R.; De Assunão, L.S.; Oliveira, P. V.; Vanetti, M.C.D.; Bazzolli, D.M.S.; Kasuya, M.C.M. Enrichment of Pleurotus Ostreatus Mushrooms with Selenium in Coffee Husks. Food Chem. 2012, 131, 558–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reczyński, W.; Muszyńska, B.; Opoka, W.; Smalec, A.; Sułkowska-Ziaja, K.; Malec, M. Comparative Study of Metals Accumulation in Cultured in Vitro Mycelium and Naturally Grown Fruiting Bodies of Boletus Badius and Cantharellus Cibarius. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2013, 153, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savic, M.; Andjelkovic, I.; Duvnjak, D.; Matijasevic, D.; Avramovic, A.; Pesic-Mikulec, D.; Niksic, M. The Fungistatic Activity of Organic Selenium and Its Application to the Production of Cultivated Mushrooms Agaricus Bisporus and Pleurotus Spp. Arch. Biol. Sci. 2012, 64, 1455–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turlo, J.; Gutkowska, B.; Herold, F.; Blazewicz, A.; Kocjan, R. Relationship between Sodium Selenite Concentration in Culture Media and Heavy Metal Uptake by Lentinula Edodes (Berk.) in Mycelial Cultures. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2009, 18, 1035–1038. [Google Scholar]

- Turło, J.; Gutkowska, B.; Herold, F.; Klimaszewska, M.; Suchocki, P. Optimization of Selenium-Enriched Mycelium of Lentinula Edodes (Berk.) Pegler as a Food Supplement. Food Biotechnol. 2010, 24, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowska, E.; Klimaszewska, M.; Strączek, T.; Schneider, K.; Kapusta, C.; Podsadni, P.; Łapienis, G.; Dawidowski, M.; Kleps, J.; Górska, S.; et al. Selenized Polysaccharides – Biosynthesis and Structural Analysis. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 198, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaleta, B.; Górski, A.; Zagożdżon, R.; Cieślak, M.; Kaźmierczak-Barańska, J.; Nawrot, B.; Klimaszewska, M.; Malinowska, E.; Górska, S.; Turło, J. Selenium-Containing Polysaccharides from Lentinula Edodes—Biological Activity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihova, S.; Godjevargova, T. Biosorption of Heavy Metals from Aqueous Solutions. J. Int. Res. Pub 2001, 1, 1311. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, G.; Viraraghavan, T. Heavy-Metal Removal from Aqueous Solution by Fungus Mucor Rouxii. Water Res. 2003, 37, 4486–4496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eide, D.J. Homeostatic and Adaptive Responses to Zinc Deficiency in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae *. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 18565–18569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staats, C.C.; Kmetzsch, L.; Schrank, A.; Vainstein, M.H. Fungal Zinc Metabolism and Its Connections to Virulence. 2013, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gharieb, M.M. The Kinetics of 75 [Se]-Selenite Uptake by Saccharomyces Cerevisiae and the Vacuolization Response to High Concentrations. Mycol. Res. 2004, 108, 1415–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazard, M.; Blanquet, S.; Fisicaro, P.; Labarraque, G.; Plateau, P. Uptake of Selenite by Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Involves the High and Low Affinity Orthophosphate Transporters. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 32029–32037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDermott, J.R.; Rosen, B.P.; Liu, Z. Jen1p: A High Affinity Selenite Transporter in Yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 2010, 21, 3934–3941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wang, B.; Zhang, D.; Wu, Y. Selenium Uptake, Tolerance and Reduction in Flammulina Velutipes Supplied with Selenite. PeerJ 2016, 2016, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turło, J.; Gutkowska, B.; Kałucka, M.; Bujak, M. Accumulation of Zinc by the Lentinus Edodes (Berk.) Mycelium Cultivated in Submerged Culture. Acta Pol. Pharm. - Drug Res. 2007, 64, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Clever, H.L.; Derrick, M.E.; Johnson, S.A. The Solubility of Some Sparingly Soluble Salts of Zinc and Cadmium in Water and in Aqueous Electrolyte Solutions. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. data 1992, 21, 941–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks; WH The Dissociation of the Selenates of Zinc and Cadmium in Water. J.Chem.Soc.Resumed 1934, 1010–1012. [CrossRef]

- Moriya, H.; Sekine, T. A Solvent-Extraction Study of Zinc (II) Complexes with Several Divalent Anions of Carboxylic and Inorganic Acids. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1974, 47, 747–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somer, G.; Yilmaz, Ü.T. Interference between Selenium and Some Trace Elements during Polarographic Studies and Its Elimination. Talanta 2005, 65, 598–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feroci, G.; Badiello, R.; Fini, A. Interactions between Different Selenium Compounds and Zinc, Cadmium and Mercury. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2005, 18, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turło, J.; Gutkowska, B.; Herold, F.; Luczak, I. Investigation of the Kinetics of Selenium Accumulation by Lentinula Edodes (Berk.) Mycelial Culture by Use of Reversed-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Fluorimetric Detection. Acta Chromatogr. 2009, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.A.; Smith, F. Colorimetric Method for Determination of Sugars and Related Substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszczyk, A.; Zych, M.; Zielniok, K.; Krata, N.; Turło, J.; Klimaszewska, M.; Zagożdżon, R.; Kaleta, B. The Effect of Novel Selenopolysaccharide Isolated from Lentinula Edodes Mycelium on Human T Lymphocytes Activation, Proliferation, and Cytokines Synthesis. Biomolecules 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turło, J.; Gutkowska, B.; Malinowska, E. Relationship between the Selenium, Selenomethionine, and Selenocysteine Content of Submerged Cultivated Mycelium of Lentinula Edodes (Berk.). Acta Chromatogr. 2007, 36–48. [Google Scholar]

- Klimaszewska, M.; Górska, S.; Dawidowski, M.; Podsadni, P.; Turło, J. Biosynthesis of Se-Methyl-Seleno-l-Cysteine in Basidiomycetes Fungus Lentinula Edodes (Berk.) Pegler. Springerplus 2016, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, B.T.; Sehrawat, S. Immunity and Immunopathology to Viruses: What Decides the Outcome? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 10, 514–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipkova, M.; Wieland, E. Surface Markers of Lymphocyte Activation and Markers of Cell Proliferation. Clin. Chim. acta 2012, 413, 1338–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibrián, D.; Sánchez-Madrid, F. CD69: From Activation Marker to Metabolic Gatekeeper. Eur. J. Immunol. 2017, 47, 946–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatrova, A.N.; Mityushova, E. V; Vassilieva, I.O.; Aksenov, N.D.; Zenin, V. V; Nikolsky, N.N.; Marakhova, I.I. Time-Dependent Regulation of IL-2R α-Chain (CD25) Expression by TCR Signal Strength and IL-2-Induced STAT5 Signaling in Activated Human Blood T Lymphocytes. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0167215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jubel, J.M.; Barbati, Z.R.; Burger, C.; Wirtz, D.C.; Schildberg, F.A. The Role of PD-1 in Acute and Chronic Infection. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Du, Y.; Rashid, A.; Ram, H.; Savasli, E.; Pieterse, P.J.; Ortiz-Monasterio, I.; Yazici, A.; Kaur, C.; Mahmood, K.; et al. Simultaneous Biofortification of Wheat with Zinc, Iodine, Selenium, and Iron through Foliar Treatment of a Micronutrient Cocktail in Six Countries. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 8096–8106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayanati, M.; Al-Tawaha, A.R.; Al-Taey, D.; Al-Ghzawi, A.L.; Abu-Zaitoon, Y.M.; Shawaqfeh, S.; Al-Zoubi, O.; Al-Ramamneh, E.A.D.; Alomari, L.; Al-Tawaha, A.R.; et al. Interaction between Zinc and Selenium Bio-Fortification and Toxic Metals (Loid) Accumulation in Food Crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koszinowski, U.H.; Reddehase, M.J.; Jonjic, S. The Role of CD4 and CD8 T Cells in Viral Infections. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1991, 3, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Mentzer, A.J.; Liu, G.; Yao, X.; Yin, Z.; Dong, D.; Dejnirattisai, W.; Rostron, T.; Supasa, P.; Liu, C.; et al. Broad and Strong Memory CD4+ and CD8+ T Cells Induced by SARS-CoV-2 in UK Convalescent Individuals Following COVID-19. Nat. Immunol. 2020, 21, 1336–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trickett, A.; Kwan, Y.L. T Cell Stimulation and Expansion Using Anti-CD3/CD28 Beads. J. Immunol. Methods 2003, 275, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).