Preprint

Article

Comparing Our Abilities on Instagram Makes Us Unhappy – An Exposition Study with Respect to Ability- vs. Opinion-Based Social Comparisons on Instagram

Altmetrics

Downloads

143

Views

50

Comments

0

A peer-reviewed article of this preprint also exists.

This version is not peer-reviewed

Submitted:

31 August 2023

Posted:

04 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Alerts

Abstract

Social networks are experiencing great popularity, with Instagram currently being the most intensively used network. On these platforms, users are continuously exposed to self-relevant information that fosters social comparisons. A distinction is made between ability-based and opinion-based comparison dimensions. To experimentally investigate the influence of these comparison dimensions on users' subjective well-being, an online exposition experiment (N = 409) was conducted. In a preliminary study (N = 107), adequate exposition stimulus material was selected in advance. The results of the main study indicated that exposition of ability-related social comparisons in the context of social media elicited lower well-being than exposition of opinion-related social comparisons. Theoretical and practical implications of the findings were discussed and suggestions for future work were outlined.

Keywords:

Subject: Social Sciences - Behavior Sciences

1. Introduction

Facebook, Twitter, Instagram - with up to 2.7 billion active users per month, so-called social networking sites (SNSs) have been growing in popularity for two decades (Statista, 2023). On SNSs, users create their own electronic profile and can interact with other users in a variety of ways. This results in new forms of interaction that have also aroused research interest (Wilson et al., 2012). Numerous studies have already elaborated on the motivation to use SNSs and observed both positive and negative effects of SNSs use (Alhabash & Ma, 2017; Lee et al., 2015; Meier & Schäfer, 2018; Sagioglou & Greitemeyer, 2014; Sheldon & Bryant, 2016). SNSs are about people. Therefore, use of SNSs is regularly connected with the elicitation of social comparisons. They are frequently triggered when users are confronted with information about another individual that is related to their self (Mussweiler et al., 2006). Such information is omnipresent on SNSs, which is why social networks provide such a powerful platform for the elicitation of social comparisons online. A highly relevant question in terms of personal, organizational, and societal considerations is what are the consequences of such comparisons on the users’ well-being? This question was investigated in our study.

1.1. Social networking sites (SNS)

Ellison and Boyd (2013) defined social networking sites (SNSs) as networked communication platforms where users create uniquely identifiable profiles that may include their own content as well as content from other users. Diverse content can be both consumed and produced. Interactions with this user-generated content are also possible. In addition, connections to people published by users can be accessed and viewed by other users. In general, SNSs differ in their designs and functions. The most popular functions include sending private messages, liking posts, uploading one's own photos, and interacting with posts from other users (Statista, 2023). Options such as creating group chats, joining group pages, or creating events are also available on many SNSs.

Depending on the available functions, SNSs can differ accordingly in persistence, connections, visibility, and editability (Treem & Leonardi, 2012). In addition, each SNS has a different focus. For example, Instagram is an image-based social network, while Twitter is a predominantly text-based social network.

The platform Facebook currently has the highest number of users, with over 2.7 billion monthly active users (Statista, 2023). However, the most intensively used SNS is Instagram (Alhabash & Ma, 2017). Instagram is characterized as a photo-based SNS by the fact that photos can be edited and shared in one's own profile (Instagram, 2020). In addition, moments from everyday life can be shared, which are visible for 24 hours in the so-called "story". It is also possible to privately send photos, videos, and messages to other users. The number of monthly active Instagram users doubled from 2013 to 2018, so that Instagram now has around two billions of active accounts (Statista, 2023). This development also aroused research interest regarding Instagram, so that scientific papers dealt with it. Since SNSs offer a new type of communication and interaction due to the functions mentioned (Wilson et al., 2012), more intensive research must be conducted in the future to determine what the offline behavior of users looks like, what the motivation for use is, and how this can be compared with online behavior. The described design of SNSs requires, among other things, that users are confronted with the posted content of other users. Thus, confronted with social information, social comparisons automatically take place.

1.2. Social comparisons

Festinger (1954) postulated in his theory of social comparison that comparing the self with others is a basic human need. The standard of comparison are people that are perceived as similar on relevant dimensions such as performance, success, and health. In his theory, Festinger (1954) focused primarily on the motivational reasons for comparison and described that despite the existence of objective standards, subjective information gained through social comparison has still an influence. These comparisons take place whenever information about other individuals is available (Mussweiler et al., 2006). Information about the self can be gained from those comparisons and self-evaluation occurs. From a systematic point of view, three different comparison directions are distinguished, i.e., lateral, upward, and downward. Therefore, social comparisons refer either to similar others or superior or inferior others. These comparison processes can take place consciously, but also unconsciously (cf., Suls et al., 2002).

Individuals compare themselves to others to be able to assess their own abilities or opinions in relation to the comparison persons (Lee, 2014). SNSs provide platforms on which social comparisons are enabled, as self-referential information is continuously presented and retrievable (cf., Mussweiler et al., 2006; Ozimek & Förster, 2017; 2021). Instagram, as an image-based medium, provides quick and easy ways to access millions of profiles and use them to collect social comparison information, and allows people to present themselves (de Vries et al., 2018; Ozimek, Lainas et al., 2023; Stapleton et al., 2017). Accordingly, Instagram can serve the basic need for social comparison described above.

Sheldon and Bryant (2016) generally identified four motives for using Instagram, of which, in addition to photo or video documentation, creativity, and coolness, observing others is an important motive for use. According to Mussweiler et al. (2006), social comparison automatically results from observing others. It has also already been shown for Facebook that the need to compare oneself functions as a relevant motive for use. Thus, in addition to the need for belonging and the need for self-presentation, the need to compare is added (Krämer & Winter, 2008; Lee, 2014; Nadkarni & Hofmann, 2012; Ozimek & Förster, 2017; 2021).

The Social Online Self-Regulation Theory (SOS-T; Ozimek & Förster, 2021) embeds the motives for using SNSs in an overarching framework and considers SNSs as means for the purpose of self-regulation. Self-regulation describes a process by which one's thoughts and actions are controlled to achieve positive end states and avoid negative end states (Carver & Scheier, 1982). This process is mostly unconscious and occurs mostly automatically (Förster & Jostmann, 2012). It is assumed that people have motives in terms of higher-level goals, which in turn activate specific goals that can be achieved by different means (Higgins, 1996; 1997).

The numerous opportunities for social comparison present on SNSs are likely to influence users' subjective well-being. For example, the inference of own superiority is likely to enhance subjective well-being, whereas the inference of own inferiority is likely to reduce subjective well-being.

2.4. Subjective well-being, social comparisons, and SNSs

In general, different consequences of social comparisons may arise. The construct of subjective well-being (SWB) turns out to be particularly important in this context. SWB constitutes a multidimensional construct which is divided into an affective and a cognitive component (Diener, 1984).

The affective component includes positive and negative affect, whereas the cognitive component refers to life satisfaction and evaluation of self. In this context, affect refers to a persistent state that manifests itself in short-term moods and emotions and is influenced by internal and external factors (Peters, 1997). Life satisfaction refers to a comprehensive cognitive evaluation process of quality of life based on comparing one’s own life situation with an adequate situational standard (Diener et al., 1985). Our approach is based on the tripartite model of happiness (Lucas & Diener, 2015) which combines measures of life satisfaction, positive affect, and negative affect.

In addition, we included self-esteem as an indicator of subjective well-being which constitutes a positive characteristic of the self of happy people and connects happiness with flourishing and positive mental health (Seligman, 2011). High self-esteem is defined as the positive evaluation of one's own person and reflects positive thoughts toward the self (in contrast to negative thoughts toward the self; Rosenberg, 1965). In theory and research, stable global self-worth as the overall evaluation of the self is contrasted with state self-worth as the momentary self-worth varying depending on time and situation (Rudolph et al., 2018). In this research we focus on global self-worth.

In general, social comparisons elicited on SNSs tended to reduce subjective well-being (Appel et al., 2016; Kross et al., 2013; Lee, 2014; Ozimek & Bierhoff, 2016; 2020; Sagioglou & Greitemeyer, 2014; Steers et al., 2014; Tandoc et al., 2015; Verduyn et al., 2015). One possible explanation is that self-presentation on SNSs is overwhelmingly positive and idealized (Walther, 1995). In effect, users frequently compare their real selves with the ideal selves of others, which may result in feeling of inferiority as a consequence of the elicitation of upward comparisons that are likely to facilitate negative feelings (Gonzales & Hancock, 2011; Ozimek & Förster, 2021; Park & Baek, 2018). Specifically, initial evidence has been found that social comparisons elicited on the Instagram platform have negative repercussions on well-being (Lup et al., 2015; Stapleton et al., 2017; Ozimek, Lainas et al., 2023). In correspondence with these results, further studies, which were conducted recently, revealed a negative association between social comparisons on SNSs and subjective well-being (Brailovskaia et al., 2020; Brailovskaia & Margraf, 2020).

This pattern of results was modified after taking the distinction between active and passive use of social media into account. Whereas active users communicate directly with others (e.g., posting comments, chatting, uploading content), passive users merely consume the content elaborated by others without interacting with them (e.g., reading comments, viewing profiles; Krasnova et al., 2013). Taking this distinction into account, it became apparent that active use was associated with higher subjective well-being, while passive usage was associated with lower subjective well-being (Ozimek, Brailovskaia et al., 2023; Verduyn et al., 2017; 2021).

Another important distinction refers to ability- and opinion-oriented comparisons (Park & Baek, 2018). This distinction was originally introduced by Festinger (1954) in his groundbreaking publication on social comparisons who contrasted opinions and abilities by pointing out that opinions possess no objective basis of evaluation whereas abilities are measurable in terms of objective performance criteria. Festinger postulated that a social comparison with others who are expected to be close to one’s own position results in stable evaluations of opinions and abilities. In addition, he postulated that abilities elicit a striving to get better distinguishing them from opinions: The unidirectional upward orientation.

In the same vein, Park and Baek (2018) focused on the distinction between opinions and abilities in the context of upward and downward social comparisons. Following the Social Comparison Based Emotions model (Smith, 2000), they distinguished between upward assimilative emotions (optimism, inspiration), upward contrastive emotions (envy, depression), downward assimilative emotions (worry, sympathy), and downward contrastive emotions (schadenfreude, pride). Specifically, their results indicated that a high ability-oriented social comparison orientation led to less subjective well-being based on upward comparisons (but not based on downward comparisons). In addition, a high opinion-oriented social comparison orientation led to more subjective well-being because of upward comparisons. Their research which integrated several emotions led to complex results. But a main path of influence was revealed from ability-based comparisons via envy/depression (positive association) to satisfaction with life (negative association). Therefore, ability comparisons considerably increased envy and depression, which in turn strongly reduced satisfaction with life. This path was much stronger than the other paths considered (e.g., opinion-based comparison via worry/sympathy (positive association) to satisfaction with life (positive association)

These results indicate that the distinction between ability-oriented and opinion-oriented social comparisons is promising in terms of satisfaction with life. The implications of this distinction were investigated in this research by employing an experimental design instead of a correlative path model. Therefore, we focused on causal analysis within the SNS context.

1.5. Hypotheses

Two hypotheses were pursued which are interrelated referring to the structure of the dependent variables on the one hand and to the ability-/opinion distinction on the other hand.

H1: In correspondence with the tripartite model of happiness (Lucas & Diener, 2015) and conditions of mental health as outlined by Seligman (2011) high subjective well-being should be given if positive affect is high, negative affect is low, satisfaction with life is high and self-esteem is also high. In correspondence with this taxonomy, we proposed that the indicators of subjective well-being are correlated significantly. Thus, satisfaction with life, self-esteem and positive affect should be correlated positively whereas the three indicators should be negatively correlated with negative affect.

To investigate the relationship between ability-/opinion based social comparison and subjective well-being in terms of affect, satisfaction with life and self-esteem we employed an experimental design. Note that Park and Baek (2018) found that ability-based social comparison orientation was strongly related to decreased subjective well-being Is this pattern of results replicable experimentally and does it generalize across different measures of subjective well-being which cover both self-esteem and satisfaction with life?

The experimental manipulation was realized by deployment of two versions of social comparison information in the context of SNSs. In correspondence with the results by Park and Baek (2018) the following hypotheses were outlined: An exposition to ability-related social comparisons leads to lower subjective well-being in terms of lower positive affect (H2a), higher negative affect (H2b), lower life satisfaction (H2c), and lower self-esteem (H2d) than an exposition to opinion-related social comparisons.

2. Method

2.1. Research design

The present study adopted an experimental exposition paradigm in an online format (cf. Ozimek et al., 2021). Participants were randomly assigned either to ability-based or to opinion-based comparison groups. An online setting was chosen for the implementation of the experiment because it is highly economical (cf., Reips, 2002).

2.2. Preliminary study

To generate suitable exposition material in our main study, a preliminary study was conducted. Data was collected through an online questionnaire distributed via Qualtrics. Anyone who was of legal age and had an Instagram account was asked to participate. A total of 107 persons participated in the preliminary study, with an overrepresentation of female respondents (82.2%). The mean age of the participants was 23.92 years (SD = 4.50) and their average Instagram usage time was between 30 and 90 minutes per day.

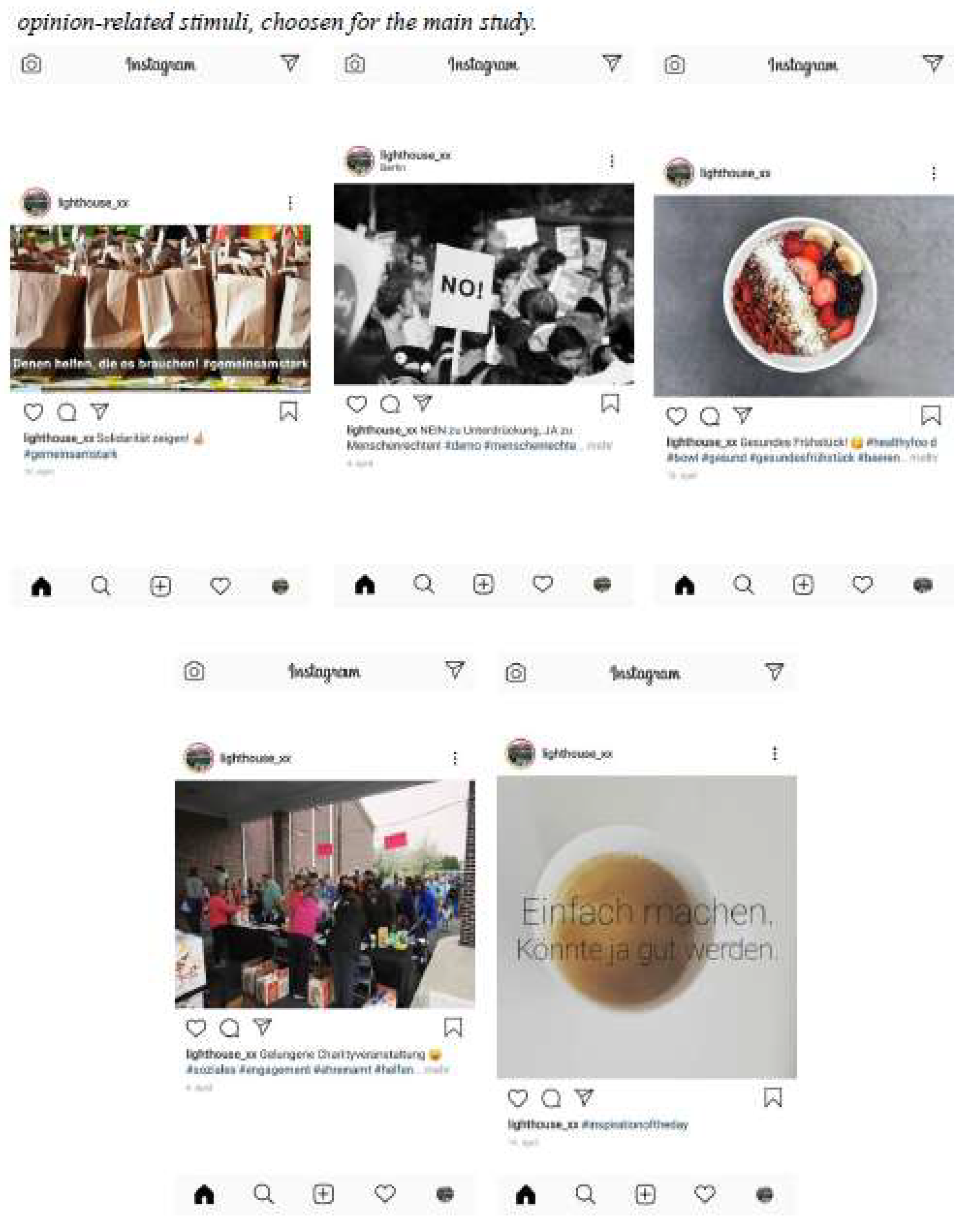

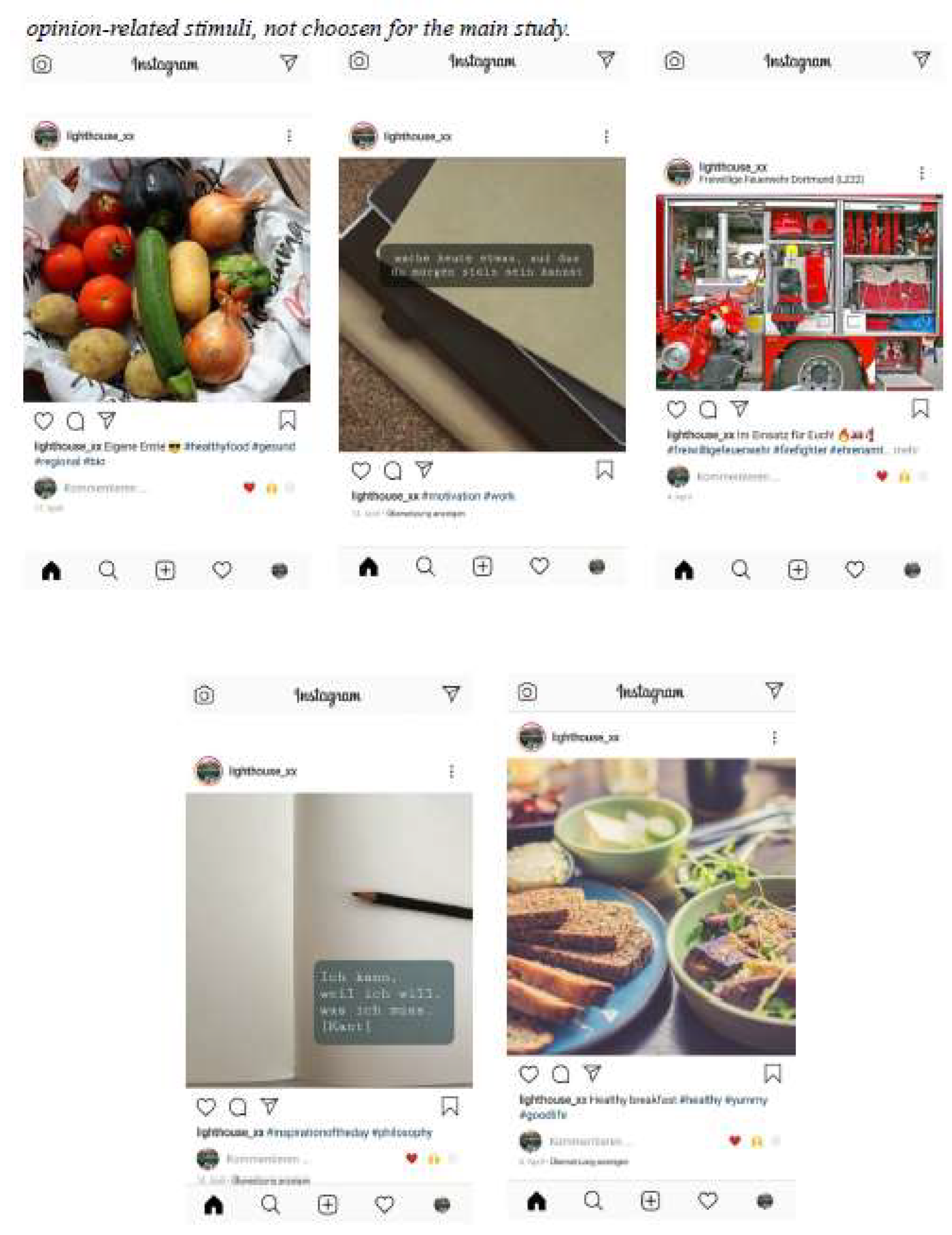

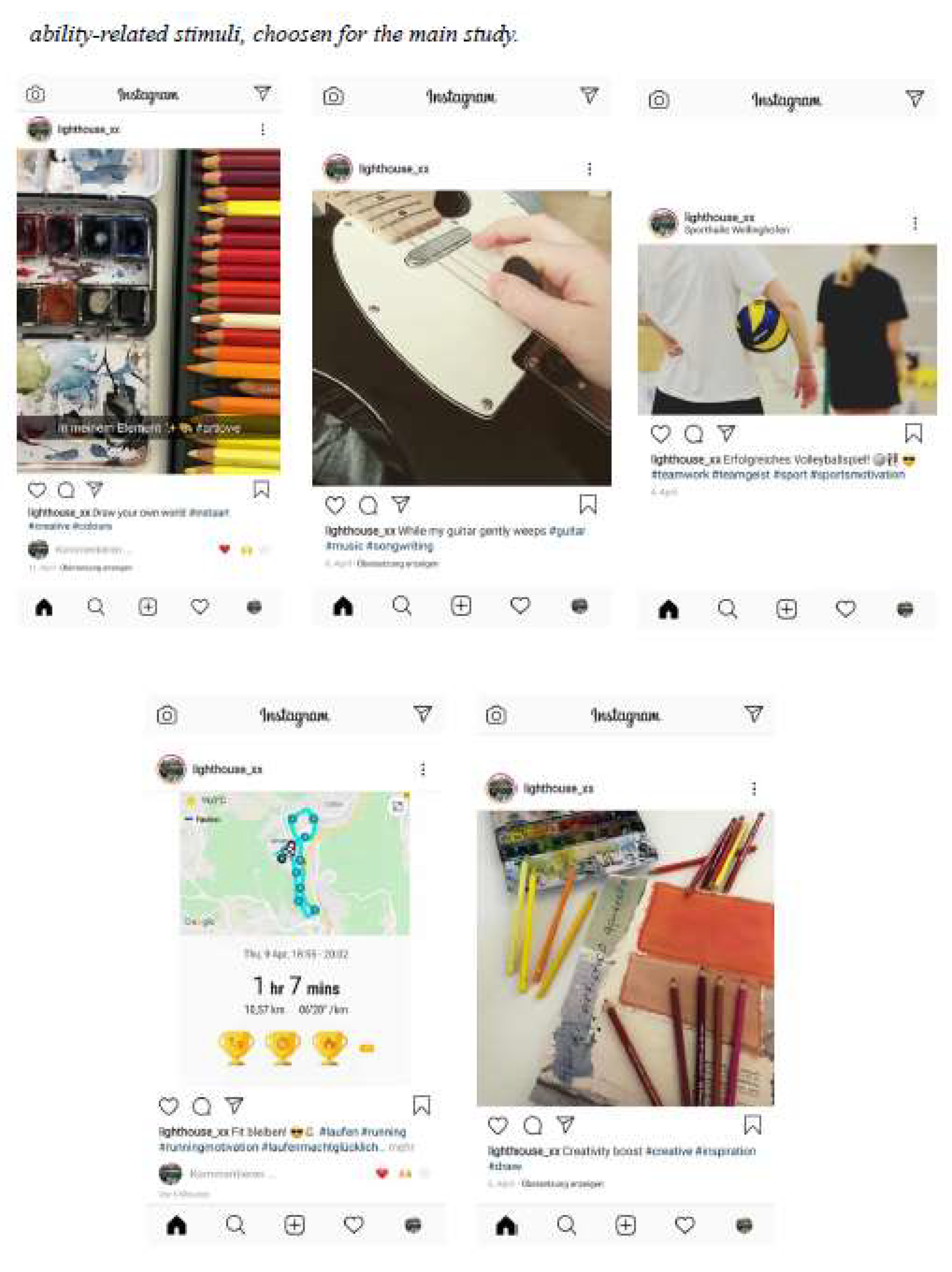

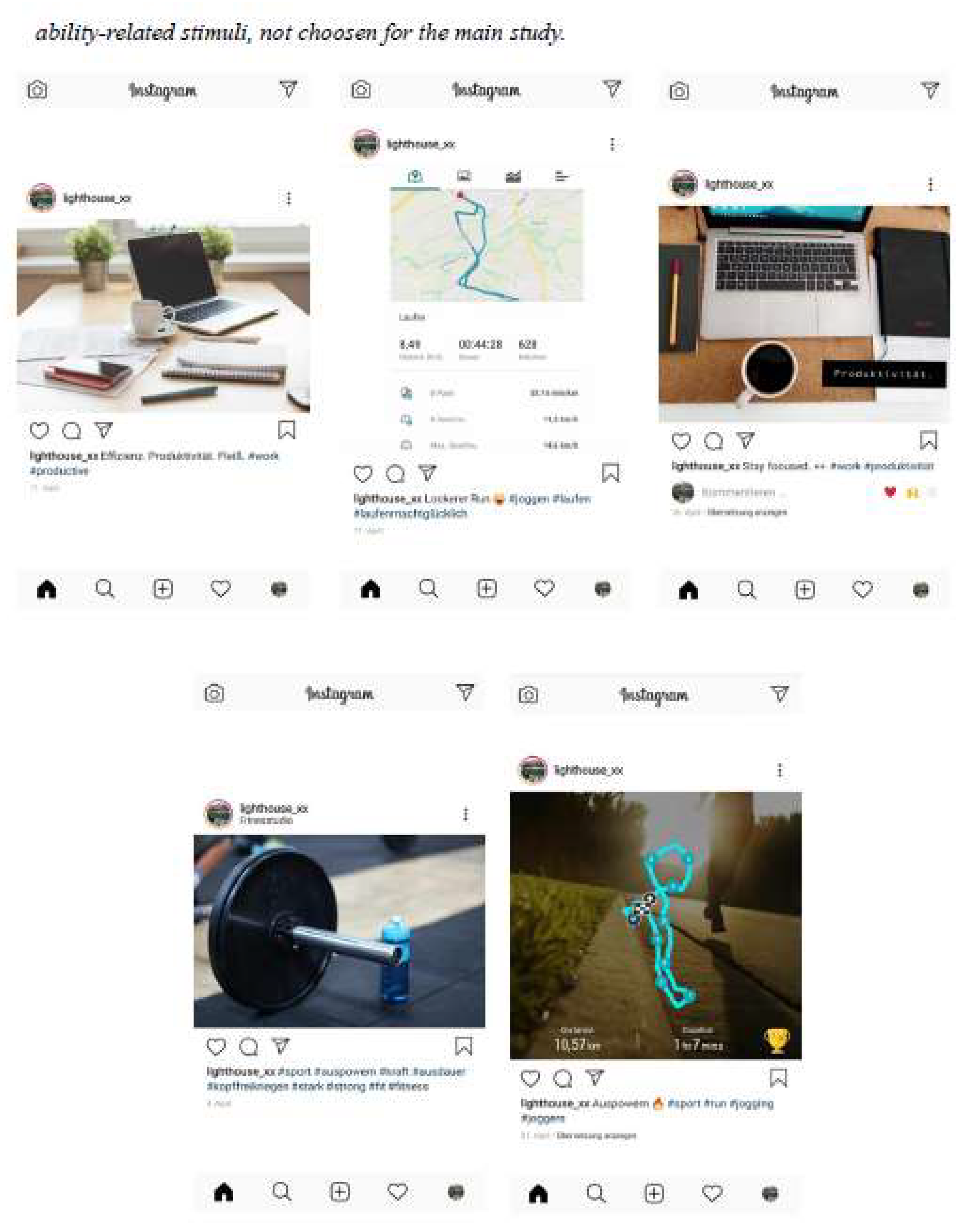

The pre-study included ten stimuli that were intended to expose to ability- or opinion-based social comparisons. The presentation of the stimuli was randomly to avoid sequence effects. In general, the stimuli looked like a screenshot from an Instagram profile (cf., APPENDIX A1-A4.) The stimuli were photos, either self-taken or license-free, tagged with appropriate hashtags to increase authenticity. A gender-neutral user profile named "lighthouse_xx" was used for this purpose. After each of the stimuli were presented, participants were asked whether the post was more likely to reflect opinions or abilities. Finally, participants could optionally express criticism in a free text field.

The basis for the stimulus selection for the main study was which stimuli most closely reflected ability and opinion, respectively. Therefore, mean ratings were considered. Values close to 0 indicated ability-related content and values close to 1 indicated opinion-related content (see APPENDIX B). Five stimuli each, which on average were closest to the intended content (ability or opinion, respectively), were selected for use in the main study (see APPENDIX A1-A4.)

2.3. Main study

2.3.1. Sample

To determine the required sample size, a sample size design was first conducted using G*Power (version 3.1.9.6; Faul et al., 2007) assuming mean effect size and a significance level of 5%. Since t-Test is the most complex statistical procedure used in the analysis, a minimum sample size of 302 was required. 415 respondents finally participated in the study. After six respondents were excluded due to incomplete data sets, 409 participants were included in the final sample. Among the participants, 338 were female (82.6%), 63 were male (15.40%), and 8 (2%) were diverse. The average age was 24.31 years (SD = 5.31) and the daily time spent on Instagram averaged between 30 and 90 minutes.

2.3.2. Procedure

The main study was also conducted on Qualtrics. Recruitment of participants was achieved via a snowball sampling technique. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were the same as in the preliminary study.

The study started with participant information and informed consent, which was followed by exposure instruction. Participants were shown, in a randomized manner, four of the selected five stimuli in the ability- or opinion-related photographs category. They were randomly assigned to the experimental groups (Nability = 198, Nopinion = 211). To ensure intensive engagement with the stimulus material, a free-text field with appropriate instructions for engagement with the material was inserted after each stimulus. Participants had to answer (in at least 30 characters) how they would describe the person who presumably posted the picture. In addition, a manipulation check was included for the manipulation check was included by asking the participants after each stimulus whether what they saw was more related to ability or opinions. After the manipulation of the independent variable was completed, the dependent variables were collected.

2.3.3. Measures

The dependent measures included three questionnaires: (positive and negative) affect, life satisfaction, and self-esteem. Life satisfaction represents the stable component of cognitive well-being. The three scales were presented in randomized order to reduce the likelihood of systematic bias due to sequence effects. This was followed by a query of demographic data (gender, age, highest education, daily Instagram usage time, and number of followers).

Affect. The affective component of subjective well-being was assessed using the German short version of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Thompson, 2007) by Randler and Weber (2015). The scale assesses positive (e.g., "active") and negative (e.g., "angry") affect on a five-point Likert scale (1 = very little/not at all to 5 = extremely) with five items each. The scale showed acceptable internal consistency of α = .74 - .79 for positive affect and α = .66 - .70 for negative affect (Randler & Weber, 2015). In the present study, acceptable reliability was also found (αpositive = .69, αnegative = .79).

Life Satisfaction. A standard measure of life satisfaction was employed. The German version of the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) by Glaesmer et al. (2011) is based on the original scale by Diener et al. (1985). Five items (e.g., "In most areas, my life matches my ideal") capture personal quality of life on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = I strongly agree to 7 = I strongly disagree). The scale achieved excellent internal consistency with an α of .92 (Glaesmer et al., 2011). High internal consistency (α = .87) was also achieved in this sample.

State Self-Esteem. State self-esteem reflects cognitive well-being. It was assessed using the State Self-Esteem Scale (SSES) originally developed by Heatherton and Polivy (1991) in a German revised version (SSES-R; Rudolph et al., 2018). Fifteen items are answered on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Three subscales, each with five items, are distinguished: performance self-esteem (e.g., "I have confidence in my abilities"), social self-esteem (e.g., "I care about the impression I make"), and appearance self-esteem (e.g., "I think I look good"). In addition, an overall scale including 15 items is viable. The authors report high internal consistencies for all subscales (αperformance = .80, αsocial = .87, αappearance = .88, and αtotal = .90). The current sample revealed high internal consistency of the SSES-R (α = .90 for the combined scale across performance, social and appearance).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptives and intercorrelations

Firstly, descriptive data (Table 1) and intercorrelations (Table 2) of the measures are reported. In general, participants reported medium ratings. An exception is the scale PANASnegative, because the ratings of negative affect were very low in general.

H1 focused on the correlation pattern of PANAS, SWLS, and SSES. In correspondence with previous research, the two subscales of the PANAS correlated significantly negatively. High positive affect implied less negative affect and vice versa. In addition, in correspondence with the hypothesis significant positive correlations between PANASpositive, the SWLS, and the SSES emerged, whereas PANASnegative displayed as expected negative correlations with the SWLS and SSES. The highest (positive) correlation was recorded between SWLS and SSES indicating 43% of common variance. Even the lowest correlation between PANASpositive and PANASnegative accounts for 12.9% of common variance. As expected, high subjective well-being is consistently captured by PANAS, SWLS, and SSES.

3.2. Manipulation check

The manipulation check examined the extent to which the manipulation achieved the intended effect, i.e., whether the respondents made a correct assignment when asked after each stimulus presentation whether its content was related more to abilities or more to opinions. Overall, the stimuli were correctly assigned. Only three stimuli were categorized incorrectly by some participants. The details of the manipulation check are summarized in Appendix C.

3.3. t-Test

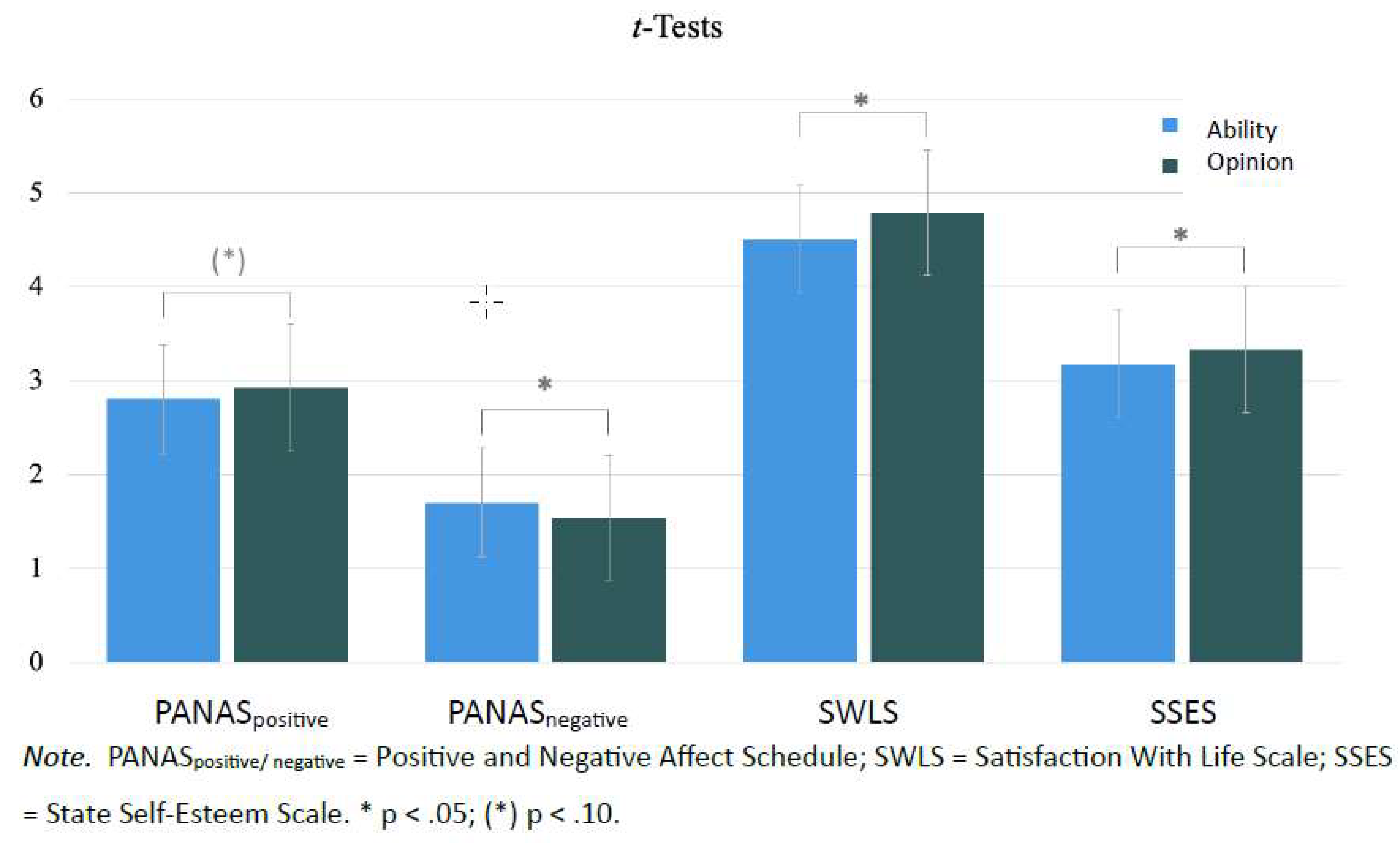

The second hypothesis stated that an exposure to ability-related social comparisons leads to lower subjective well-being than an exposure to opinion-related social comparisons. H2 was examined based on the experimental design by t-tests for independent samples. Of the 409 participants, 198 were randomly assigned to EGAbility and 211 to EGOpinion. There was only a marginally significant difference between EGAbility and EGOpinion with respect to positive affect (t(407) = -1.84, p = .067, d = 0.71), so hypothesis 2a had to be rejected. Negative affect, on the other hand, was significantly higher in EGAbility than in EGOpinion (t(382) = 2.09, p < .05, d = 0.75). This was consistent with hypothesis 2b. Also, there was a statistically significant difference in life satisfaction between EGAbility and EGOpinion in the expected direction (t(407) = -2.22, p < .05, d = 1.26). This result was consistent with hypothesis 2c. Finally, a lower self-esteem in the EGAbility than in the EGOpinion condition was observed. This difference was statistically significant (t(407) = -2.03, p < .05, d = 0.72) and was, therefore, consistent with hypothesis 2d. The results of these t-tests are graphically illustrated in Figure 1.

4. Discussion

A special feature of this research is that the between-subjects design of this study allows a causal interpretation of results: Ability-based comparison information caused a reduction in psychological well-being (compared with opinion-based comparison information). This experimental effect is replicated across several indicators of quality of life and therefore represents a viable result. The questionnaires employed to measure subjective well-being (PANAS, SWLS, SSES) are standard measures which exhibited considerable reliability and validity in previous research. This study enters new territory by demonstrating a reliable difference between social comparisons based on abilities and opinions (cf., Festinger, 1954), respectively, which is relevant in applied settings of the online community in general and on SNSs in particular. In summary, ability-based social comparison information is potentially more damaging in terms of self-evaluation than opinion-based information.

Regarding the research hypothesis, results indicated in correspondence with H1 that the dependent variables positive and negative affect, life satisfaction and self-esteem are correlated significantly with each other. They represent different facets of happiness with negative affect focusing on the negative pole of subjective well-being, whereas positive affect, life satisfaction and self-esteem represent the positive pole. These results correspond with earlier studies which revealed that positive affect and life satisfaction, which represent the affective and cognitive components of subjective well-being, are correlated with each other, whereas negative affect is a negative concomitant of happiness. This approach agrees with the widely accepted tripartite model of happiness (Lucas & Diener, 2015) which combines life satisfaction, positive affect, and negative affect as correlated dimensions. In addition, self-esteem was included, which constitutes a positive characteristic of happy people, and connects happiness with flourishing and mental health (Seligman, 2011).

In correspondence with H2, the results indicated that an exposure to ability-related social comparisons in the context of social media led to higher negative affect (H2b), lower life satisfaction (H2c), and lower self-esteem (H2d) than exposure to opinion-related social comparisons. For positive affect, however, only a marginally significant difference between the two experimental conditions occurred, which is why hypothesis H2a was only weakly supported.

The results with respect to the hypotheses were consistent with previous research by Park and Baek (2018), but instead of being correlational, they were based on random assignment based on an experimental design. Therefore, the negative consequences of exposure to ability-related information in contrast to opinion-related information, which were detected in this experiment are likely to represent causal influences instead of mere associations. The interpretation is that ability-related comparison information weakens subjective well-being as measured by several indicators of quality of life. Note that the general trend of the results seems to indicate that ability-related information reduced subjective well-being. Therefore, the overall pattern of results indicated that H2 was mostly confirmed.

One factor which could contribute to the stronger impact of ability-related social comparison information on well-being (cf., H2) might be that ability-related social comparisons contrast with opinion-related social comparisons automatically instigated (De Vries et al., 2018; Mussweiler et al., 2006; Stapleton et al., 2017). Further research is needed to cast new light on this issue. such as the additional inclusion of comparison direction (up or down) or kind of comparison process (assimilation or contrast).

The results of this study confirm research findings of Ozimek and Bierhoff (2020) who in three investigations observed decreased self-esteem and higher depressive tendencies as a consequence of socially comparative activities on SNSs. Furthermore, the authors revealed a systematic association of passive SNSs use with higher depressive tendencies, mediated by higher ability-related comparison orientation and lower self-esteem.

The findings obtained here are pertinent to theories such as social comparison theory (Festinger, 1954), social comparison orientation (Gibbons & Buunk, 1999), and also to the Social Online Self-Regulation Theory (SOS-T, Ozimek & Förster, 2021).

Alternative interpretations based on other theories should also be considered. For example, objective self-awareness theory (Duval & Wicklund, 1972) postulates that self-confrontation or self-reflection directs attention from the environment toward the self. An individual's attention is then turned inwardly becoming an object of one's own awareness. Under conditions of increased self-awareness, the intensity of affects tends to be increased. Furthermore, increased self-awareness enhances the awareness of discrepancies between real and imagined self. As a consequence, individuals tend to consider themselves more negatively when a negative discrepancy between real and imagined self is perceived. In the SNSs context, this would reinforce the negative effect on well-being of comparing the real-self with idealized selves on SNSs (cf. Gonzales & Hancock, 2011; Walther, 1995). This assumption deservers further examination. However, objective self-awareness theory does not differentiate between ability-based and opinion-based comparisons, which was the focus of this research. Therefore, the theory must be refocused before it is possible to apply it to the contrast between ability-based and opinion-based comparisons.

With respect to application, the findings of this work are of practical relevance for clinical psychology. Whether SNSs use represents dysfunctional or functional means of self-regulation (cf., Ozimek & Förster, 2021) has corresponding implications for clinically relevant factors. Well-being plays an essential role in relation to psychopathological processes, especially with respect to affective disorders such as depression. Therefore, it is important to study the mechanisms and effects of SNSs use to facilitate more conscious goal-directed use that is not harmful to mental health, but beneficial for the quality of life.

Thus, further studies should be devoted to the question what can be done to make the consequences of using SNSs more positive. In the case of Instagram, there is already a so-called "Well-being Team" (Instagram, 2020), which works on this issue. For example, it was established that photos digitally edited with Instagram would receive a license plate, which could reduce the negative impact of comparing real-selves with idealized representations of persons. In some cases, likes have also been turned off and alerts have been introduced when searching hashtags on sensitive topics such as anorexia or depression, pointing to sources of help. Within this framework, additional measures might be incorporated to reduce negative consequences of use of social network sites. For example, the relatively strong impact of ability-based comparison information on subjective well-being might be highlighted and provided with warnings for the users.

5. Limitations

Although the preliminary study brought about an optimal selection of test materials in terms of abilities and opinions, the results of the present work should be understood in the light of several limitations. First, the sample of this study was relatively homogenous with respect to age (i.e. young adults). Although SNS use decreases with increasing age (Ozimek & Bierhoff, 2016), which is why most young adults are represented on SNSs, it would be desirable to include more older respondents in the sample which is also unbalanced with regard to participants’ gender because significantly less men than women participated in the study. These biased sample characteristics limit the representativeness of the research reported here and attention should be directed to a balanced ratio of women and men in future studies. However, previous literature did not indicate any relevant effect on the results in this regard.

Second, the experimental design focused on EGAbility and EGOpinion groups whereas an explicit control group was not included in the research design. Therefore, the experimental groups constituted base lines for each other. Although in general the use of an explicit control group is desirable, most of the time researchers compare two or more experimental groups with each other. Because the experimental groups represented adequately the research hypothesis contrasting ability-based and opinion-based conditions the design is suitable for the test of the experimental hypothesis.

Third, this research exclusively focused on Instagram, which represents the fastest growing and most intensively used SNS (Alhabash & Ma, 2017; Sheldon & Bryant, 2016). Instagram is an image-based platform, which is important to consider when making generalized statements about SNSs. The results of the experimental study primarily apply to image-based SNSs. Since previous research tended to focus on the Facebook platform, the present findings extend the generalizability of previous findings by examining a different SNS.

Fourth, our research design was a reduced version of the research design employed by Park and Baek (2018), because we only considered the comparison dimension and did not examine the Social Comparison Based Emotions model as a whole (Smith, 2000). The reason is that we were interested in obtaining experimental results on the effects of ability-based and opinion-based social comparisons, respectively, on well-being. It seems to be hardly feasible to run the test of the complete Smith (2000) model on the basis of a between-subjects experimental design. Note that Park and Baek (2018) employed a within-subjects design. Nevertheless, replication based on the overall model based on a between-subject design seems to be within the scope of the exposure paradigm and should rather be explored in the context of longitudinal research. The comparison of our sample with the sample of Park and Baek is instructive because Park and Baek employed a national sample of internet users which was representative of Korean internet users, whereas our study was based on a convenient sample of internet users. Therefore, our sample is not representative of German internet users. But it is hardly possible to implement an experimental design within a representative sample. Nevertheless, the results of Park and Baek (2018) revealed convincingly that the focus on ability turns out to be detrimental (relative to the focus on opinion) in terms of consequences for psychological well-being.

The current study found significant differences in well-being depending on the elicitation of ability- and opinion-related comparisons, which were compatible with the original results by Park and Baek (2018). With respect to future research, the inclusion of further model components is desirable including the direction of comparison (upward or downward) and the process of comparison (assimilation or contrast).

Data availability: The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study will be made available in the OSF repository. The link will be shared – because of the double-blind peer review process – after acceptance of the paper.

Conflict of Interest: none.

Declarations: We declare that our study was approved by the local ethical committee of XXX. We declare that there are no potential conflicts of interests, and that informed consent was given by all participants.

APPENDIX

APPENDIX A1

APPENDIX A2

APPENDIX A3

APPENDIX A4

APPENDIX B

Stimulus-choice of the pre-study

| Stimulus | N | Min | Max | M | SD | PANASΔ |

| Demo | 107 | 1 | 2 | 1.03 | 0.17 | -1.53 |

| Soli | 107 | 1 | 2 | 1.06 | 0.23 | -1.71 |

| Slogan2 | 107 | 1 | 2 | 1.06 | 0.23 | -1.37 |

| Slogan1 | 107 | 1 | 2 | 1.08 | 0.28 | -1.36 |

| Slogan3 | 107 | 1 | 2 | 1.09 | 0.29 | -1.19 |

| Breakfast | 107 | 1 | 2 | 1.14 | 0.35 | -1.51 |

| Charity | 107 | 1 | 2 | 1.15 | 0.36 | -1.51 |

| Breakfast2 | 107 | 1 | 2 | 1.19 | 0.39 | -1.45 |

| Harvest | 107 | 1 | 2 | 1.38 | 0.49 | -1.44 |

| Fire department | 107 | 1 | 2 | 1.57 | 0.50 | -1.46 |

| Guitar | 107 | 1 | 2 | 1.92 | 0.28 | -1.15 |

| Arts2 | 107 | 1 | 2 | 1.86 | 0.35 | -1.40 |

| Volleyball | 107 | 1 | 2 | 1.83 | 0.38 | -1.21 |

| Arts | 107 | 1 | 2 | 1.81 | 0.39 | -1.54 |

| Run2 | 107 | 1 | 2 | 1.78 | 0.42 | -1.15 |

| Run1 | 107 | 1 | 2 | 1.75 | 0.44 | -1.22 |

| Run3 | 107 | 1 | 2 | 1.68 | 0.47 | -1.07 |

| Barbell | 107 | 1 | 2 | 1.53 | 0.50 | -1.19 |

| Efficiency | 107 | 1 | 2 | 1.36 | 0.48 | -1.18 |

| Fokus | 107 | 1 | 2 | 1.29 | 0.46 | -1.22 |

Note. Min = Minimum (1) = Opinion; Max = Maximum (2) = Ability; M = Mean; SD = standard deviation; PANASΔ = Difference of PANASpositive- und PANASnegative.

APPENDIX C

Manipulation Check

| „Opinion“ | „Ability“ | ||||

| Stimulus-Name | Ngesamt | N | % | N | % |

| Ability-based stimuli | |||||

| Guitar | 157 | 37 | 23.6 | 120 | 76.4 |

| Volleyball | 163 | 50 | 30.7 | 113 | 69.3 |

| Arts1 | 161 | 50 | 31.1 | 111 | 68.9 |

| Arts2 | 156 | 61 | 39.1 | 95 | 60.9 |

| Run2 | 155 | 62 | 40.0 | 93 | 60.0 |

| Opinion-based stimuli | |||||

| Charity | 166 | 113 | 68.1 | 53 | 31.9 |

| Demo | 162 | 155 | 95.7 | 07 | 04.3 |

| Soli | 168 | 146 | 86.9 | 22 | 13.1 |

| Slogan2 | 169 | 141 | 83.4 | 28 | 16.6 |

| Breakfast | 179 | 122 | 68.2 | 57 | 31.8 |

References

- Alhabash, S. , & Ma, M. (2017). A Tale of Four Platforms: Motivations and Uses of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat Among College Students? Social Media + Society, 6305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, H. , Gerlach, A. L., & Crusius, J. (2016). The interplay between Facebook use, social comparison, envy, and depression. ( 9, 44–49. [CrossRef]

- Brailovskaia, J. , & Margraf, J. (2020). Decrease of well-being and increase of online media use: Cohort trends in German university freshmen between 2016 and 2019. Psychiatry Research. [CrossRef]

- Brailovskaia, J. , Ströse, F., Schillack, H., & Margraf, J. (2020). Less Facebook use – More well-being and a healthier lifestyle? An experimental intervention study. Computers in Human Behavior. [CrossRef]

- Carver, C. S. , & Scheier, M. F. (1982). Control theory: A useful conceptual framework for personality–social, clinical, and health psychology. Psychological Bulletin. [CrossRef]

- de Vries, D. A. , Möller, A. M., Wieringa, M. S., Eigenraam, A. W., & Hamelink, K. (2018). Social Comparison as the Thief of Joy: Emotional Consequences of Viewing Strangers’ Instagram Posts. Media Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin.

- Diener, E. , Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction With Life Scale. ( 49(1), 71–75. [PubMed]

- Duval, S. , & Wicklund, R. A. (1972). A theory of objective self-awareness.

- Ellison, N. B. , & Boyd, D. M. (2013). Sociality Through Social Network Sites.

- Faul, F. , Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods. [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. (1954). A Theory of Social Comparison Processes. Human Relations. [CrossRef]

- Förster, J. , & Jostmann, N. B. (2012). What Is Automatic Self-Regulation? Zeitschrift Für Psychologie. [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, F. X. , & Buunk, B. P. (1999). Individual differences in social comparison: Development of a scale of social comparison orientation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Glaesmer, H. , Grande, G., Braehler, E., & Roth, M. (2011). The German Version of the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS): Psychometric Properties, Validity, and Population-Based Norms. European Journal of Psychological Assessment. [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, A. L. , & Hancock, J. T. (2011). Mirror, Mirror on my Facebook Wall: Effects of Exposure to Facebook on Self-Esteem. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. [CrossRef]

- Heatherton, T. F. , & Polivy, J. (1991). Development and validation of a scale for measuring state self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E. T. (1996). Activation: Accessibility, and salience. In A. W. Kruglanski & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles (S. 133–168). Guilford Press.

- Higgins, E. T. (1997). Beyond pleasure and pain. American Psychologist, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heatherton, T. F. , & Polivy, J. (1991). Development and validation of a scale for measuring state self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social psychology.

- 21. Instagram. (2020). Instagram Features.

- Krämer, N. C. , & Winter, S. (2008). Impression Management 2.0: The Relationship of Self-Esteem, Extraversion, Self-Efficacy, and Self-Presentation Within Social Networking Sites. Journal of Media Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Krasnova, H. , Wenninger, H., Widjaja, T., & Buxmann, P. (2013). Envy on Facebook: A Hidden Threat to Users’ Life Satisfaction? 11th International Conference on Wirtschaftsinformatik.

- Kross, E. , Verduyn, P., Demiralp, E., et al. (2013). Facebook use predicts declines in subjective well-being in young adults. PLoS One. [CrossRef]

- Lee, E. , Lee, J.-A., Moon, J. H., & Sung, Y. (2015). Pictures Speak Louder than Words: Motivations for Using Instagram. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. Y. (2014). How do people compare themselves with others on social network sites?: The case of Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior. [CrossRef]

- Lucas, R.E. & Diener, E. (2015). Personality and subjective well-being: Current issues and controversies. In M. Mikulincer & P.R. Shaver (Eds.), APA handbook of personality and social psychology (Vol. 4, pp. 577-599).Washington, DC: APA.

- Lup, K. , Trub, L., & Rosenthal, L. (2015). Instagram #Instasad?: Exploring Associations Among Instagram Use, Depressive Symptoms, Negative Social Comparison, and Strangers Followed. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. [CrossRef]

- Meier, A. , & Schäfer, S. (2018). The Positive Side of Social Comparison on Social Network Sites: How Envy Can Drive Inspiration on Instagram. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. [CrossRef]

- Mussweiler, T. , Rüter, K., & Epstude, K. (2006). The why, who, and how of social comparison: A social-cognition perspective. In S. Guimond (Eds.), Social Comparison and Social Psychology (S. 33–54). Cambridge University Press.

- Nadkarni, A. , & Hofmann, S. G. (2012). Why do people use Facebook? Personality and Individual Differences. [CrossRef]

- Ozimek, P. , Baer, F., & Förster, J. (2017). Materialists on Facebook: The self-regulatory role of social comparisons and the objectification of Facebook friends. Heliyon, 0449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozimek, P. , & Bierhoff, H.-W. (2016). Facebook use depending on age: The influence of social comparisons. Computers in Human Behavior. [CrossRef]

- Ozimek, P. , & Bierhoff, H.-W. (2020). All my online-friends are better than me – three studies about ability-based comparative social media use, self-esteem, and depressive tendencies. Behaviour & Information Technology, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozimek, P. , Bierhoff, H.-W., & Hanke, S. (2018). Do vulnerable narcissists profit more from Facebook use than grandiose narcissists? An examination of narcissistic Facebook use in the light of self-regulation and social comparison theory. Personality and Individual Differences. [CrossRef]

- Ozimek, P. , Brailovskaia, J., & Bierhoff, H. W. (2023). Active and passive behavior in social media: Validating the Social Media Activity Questionnaire (SMAQ). Telematics and Informatics Reports.

- Ozimek, P. , & Förster, J. (2017). The impact of self-regulatory states and traits on Facebook use: Priming materialism and social comparisons. Computers in Human Behavior. [CrossRef]

- Ozimek, P. , & Förster, J. (2021). The Social Online-Self-Regulation-Theory: A review of self-regulation in social media. Journal of Media Psychology.

- Ozimek, P. , Lainas, S., Bierhoff, H. W., & Rohmann, E. (2023). How photo editing in social media shapes self-perceived attractiveness and self-esteem via self-objectification and physical appearance comparisons. BMC Psychology.

- Park, S. Y. , & Baek, Y. M. (2018). Two faces of social comparison on Facebook: The interplay between social comparison orientation, emotions, and psychological well-being. Computers in Human Behavior. [CrossRef]

- Peters, U. H. (1997). Wörterbuch der Psychiatrie und medizinischen Psychologie.

- Randler, C. , & Weber, V. (2015). Positive and negative affect during the school day and its relationship to morningness–eveningness. Biological Rhythm Research. [CrossRef]

- Reips, U.-D. (2002). Standards for Internet-Based Experimenting. Experimental Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, A. , Schröder-Abé, M., & Schütz, A. (2018). I Like Myself, I Really Do (at Least Right Now): Development and Validation of a Brief and Revised (German-Language) Version of the State Self-Esteem Scale. European Journal of Psychological Assessment. [CrossRef]

- Sagioglou, C. , & Greitemeyer, T. (2014). Facebook’s emotional consequences: Why Facebook causes a decrease in mood and why people still use it. Computers in Human Behavior. [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.P. (2011). Flourish.

- Sheldon, P. , & Bryant, K. (2016). Instagram: Motives for its use and relationship to narcissism and contextual age. Computers in Human Behavior. [CrossRef]

- Smith, R. H. (2000). Assimilative and Contrastive Emotional Reactions to Upward and Downward Social Comparisons. In J. Suls & L. Wheeler (Eds.), Handbook of Social Comparison (S. 173–200). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, P. , Luiz, G., & Chatwin, H. (2017). Generation Validation: The Role of Social Comparison in Use of Instagram Among Emerging Adults. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. [CrossRef]

- 51. Statista. (2023). Umfrage zu den genutzten Funktionen in sozialen Netzwerken in Deutschland 2023. Welche der folgenden Funktionen nutzen Sie zumindest gelegentlich in sozialen Netzwerken? 8125.

- Steers, M.L. N. , Wickham, R. E., & Acitelli, L. K. (2014). Seeing everyone else's highlight reels: How Facebook usage is linked to depressive symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Suls, J. , Martin, R., & Wheeler, L. (2002). Social Comparison: Why, With Whom, and With What Effect? Current Directions in Psychological Science. [CrossRef]

- Tandoc, E. C. , Ferrucci, P., & Duffy, M. (2015). Facebook use, envy, and depression among college students: Is facebooking depressing? Computers in Human Behavior. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E. R. (2007). Development and Validation of an Internationally Reliable Short-Form of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Treem, J. W. , & Leonardi, P. M. (2012). Social Media Use in Organizations: Exploring the Affordances of Visibility, Editability, Persistence, and Association. SSRN Electronic Journal. [CrossRef]

- De Vries, D. A. , Möller, A. M., Wieringa, M. S., Eigenraam, A. W., & Hamelink, K. (2018). Social comparison as the thief of joy: Emotional consequences of viewing strangers’ Instagram posts. Media psychology.

- Verduyn, P. , Gugushvili, N., & Kross, E. (2021). The impact of social network sites on mental health: distinguishing active from passive use. World Psychiatry.

- Verduyn, P. , Lee, D. S., Park, J., Shablack, H., Orvell, A., Bayer, J.,... & Kross, E. (2015). Passive Facebook usage undermines affective well-being: Experimental and longitudinal evidence. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General.

- Verduyn, P. , Ybarra, O., Résibois, M., Jonides, J., & Kross, E. (2017). Do Social Network Sites Enhance or Undermine Subjective Well-Being? A Critical Review: Do Social Network Sites Enhance or Undermine Subjective Well-Being? Social Issues and Policy Review. [CrossRef]

- Walther, J. B. (1995). Relational Aspects of Computer-Mediated Communication: Experimental Observations over Time. Organization Science. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R. E. , Gosling, S. D., & Graham, L. T. (2012). A Review of Facebook Research in the Social Sciences. T. ( 7(3), 203–220. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Differences in subjective well-being depending on experimental condition.

Table 1.

Descriptives of the used measures.

| Measure | Range |

Total (N = 409) M (SD) |

EGAbility (N = 198) M (SD) |

EGOpinion (N = 211) M (SD) |

t | p | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PANASpositiv | 1-5 | 2.87 (0.72) | 2.81 (0.71) | 2.93 (0.72) | -1.84 | .067 | 0.71 |

| PANASnegativ | 1-5 | 1.62 (0.75) | 1.70 (0.82) | 1.54 (0.68) | 2.12 | .036 | 0.75 |

| SWLS | 1-7 | 4.66 (1.27) | 4.51 (1.30) | 4.79 (1.21) | -2.22 | .027 | 1.26 |

| SSES | 1-5 | 3.26 (0.72) | 3.18 (0.74) | 3.33 (0.69) | -2.03 | .043 | 0.72 |

Note. dfs = 407. M = mean; SD = standard deviation; t = t-Test of both groups; d = Cohens d; PANASpositiv/ negativ = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule; SWLS = Satisfaction With Life Scale; SSES = State Self-Esteem Scale.

Table 2.

Intercorrelations.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PANASpositive | - | ||

| 2. PANASnegative | -.197*** | - | |

| 3. SWLS | .412*** | -.448*** | - |

| 4. SSES | .428*** | -.518*** | .656*** |

Note. PANASpositive/negative = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule; SWLS = Satisfaction With Life Scale; SSES = State Self-Esteem Scale; *** p < .001.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Copyright: This open access article is published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permit the free download, distribution, and reuse, provided that the author and preprint are cited in any reuse.

MDPI Initiatives

Important Links

© 2024 MDPI (Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise stated