Submitted:

31 August 2023

Posted:

04 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

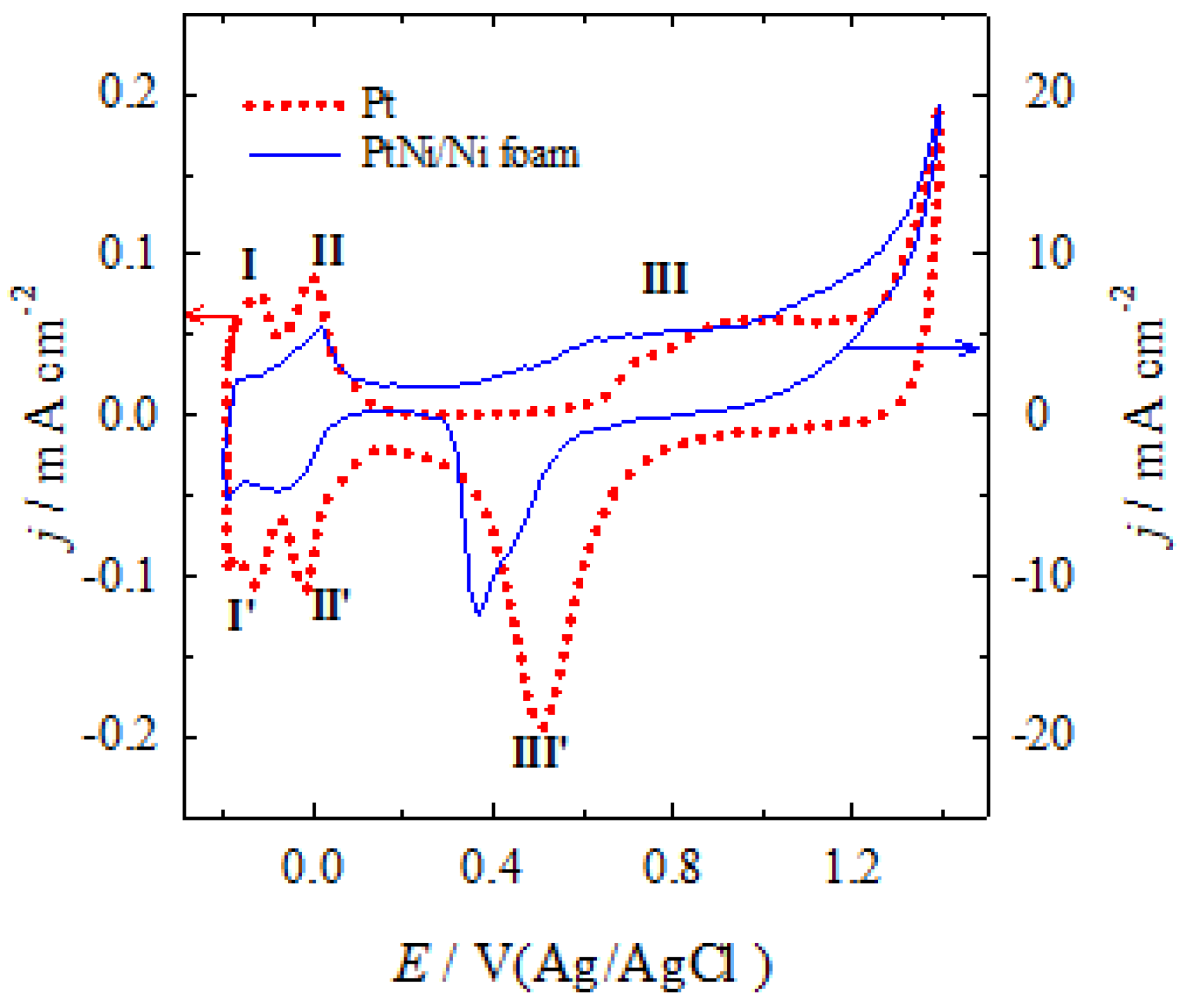

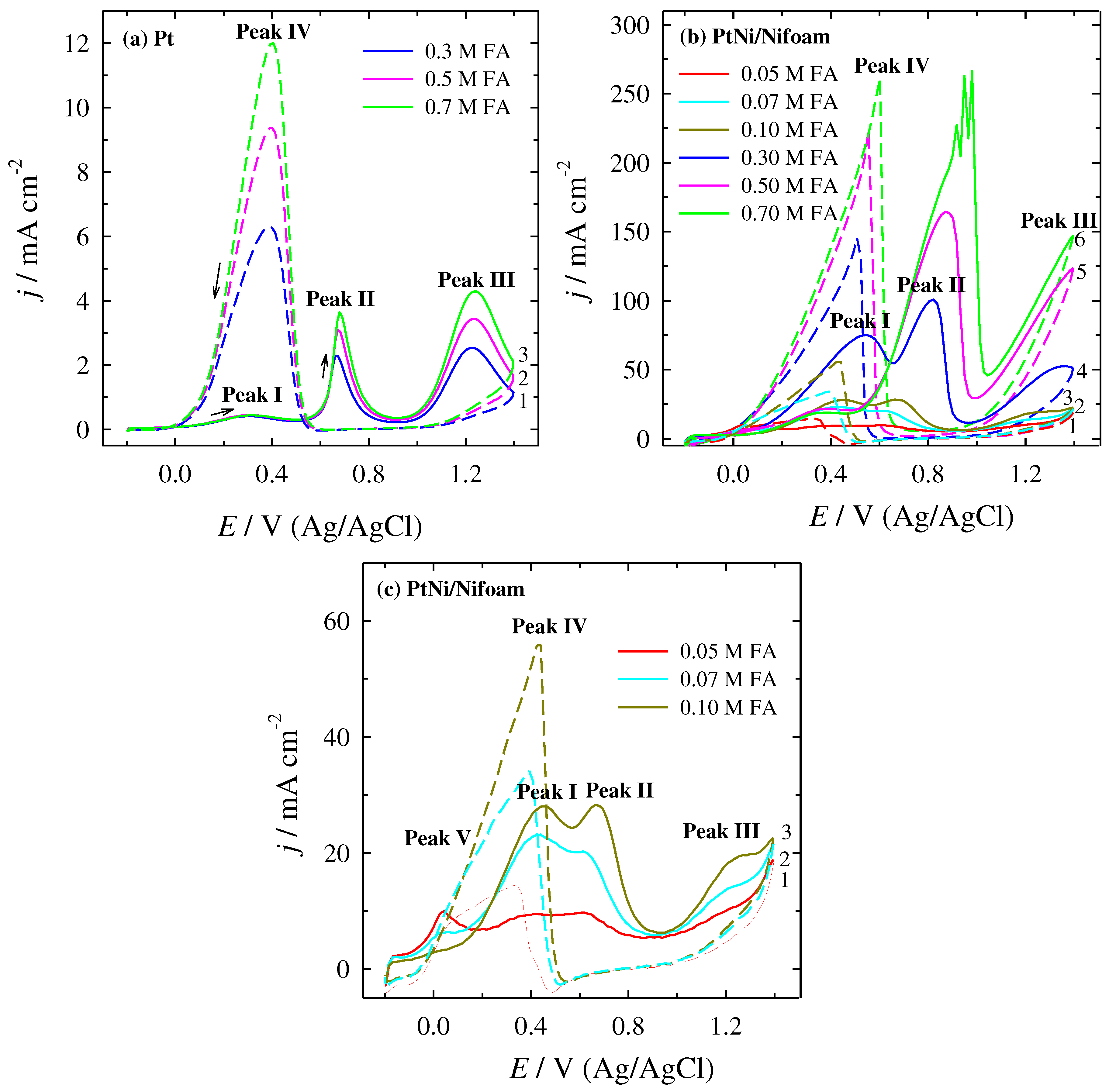

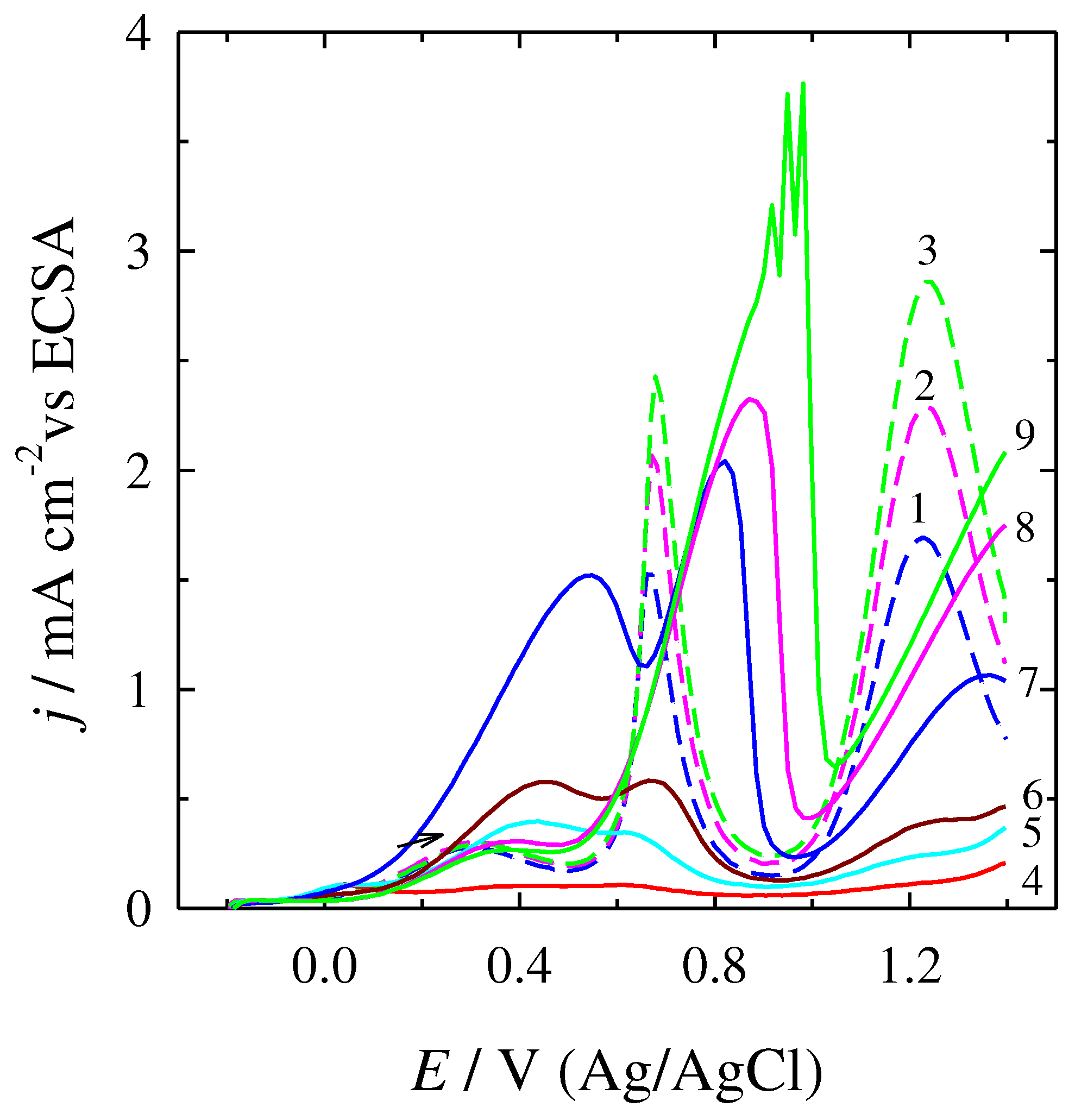

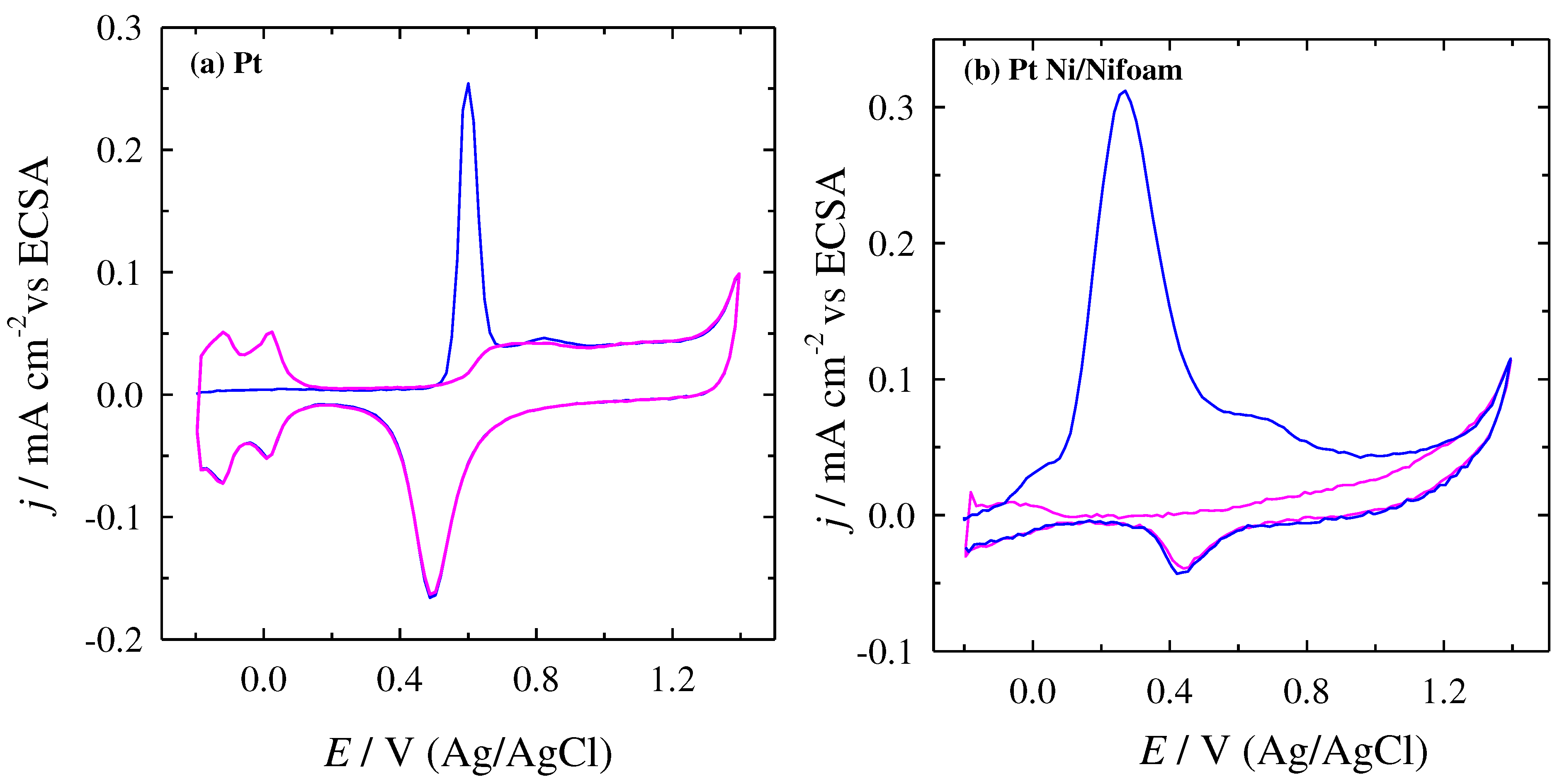

3. Results and Disscusion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ma, Z.; Legrand, U.; Pahija, E.; Tavares, J. R.; Boffito D., C. From CO2 to Formic Acid Fuel Cells. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 803–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artz, J.; Müller, T. E.; Thenert, K.; Kleinekorte, J.; Meys, R.; Sternberg, A.; Bardow, A.; Leitner, W. Sustainable Conversion of Carbon Dioxide: An Integrated Review of Catalysis and Life Cycle Assessment. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 434–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legrand, U.; Boudreault, R.; Meunier, J. L. Decoration of N-Functionalized Graphene Nanoflakes with Copper-Based Nanoparticles for High Selectivity CO2 Electroreduction towards Formate. Electrochim. Acta. 2019, 318, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekar, G. H.; Park, K.; Jung, K.-D.; Yoon, S. Recent Developments in the Catalytic Hydrogenation of CO2 to Formic acid/Formate using Heterogeneous Catalysts. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2016, 3, 882–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Heinen, M.; Jusys, Z.; Behm, R. Kinetics and mechanism of the electrooxidation of formic acid – Spectroscopical study in a flow cell. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 981–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheijen, F. J. E.; Beltramo, G. L.; Hoeppener, S.; Housmans, T. H. M.; Koper, M. T. M. The electrooxidation of small organic molecules on platinum nanoparticles supported on gold: influence of platinum deposition procedure. J. Solid-State Electrochem. 2008, 12, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, J. N.; Tiwari, R. N.; Singh, G.; Kim, K. S. Recent progress in the development of anode and cathode catalysts for direct methanol fuel cells. Nano Energy. 2013, 2, 553–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Chen, R. Direct formate fuel cells: A review. J.Power Sources. 2016, 320, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulas, B.; Kivrak, H. D. Direct Liquid Fuel Cells. Fundamentals, Advances and Future. 2021, 149-176.

- Yu, X.; Pickup, P. G. Recent advances in direct formic acid fuel cells (DFAFC). J. Power Sources. 2008, 182, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, P.; Liao, S.; Zeng, J.; Huang, X. Design, fabrication and performance evaluation of a miniature air breathing direct formic acid fuel cell based on printed circuit board technology. J. of Power Sources. 2010, 195, 7332–7337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miesse C., M.; Jung, W. S.; Jeong, K.-J.; Lee, J. K.; Lee, J.; Han, J.; Yoon, S. P.; Nam, S. W.; Lim, T.-H. ; Hong. S.-A. Direct formic acid fuel cell portable power system for the operation of a laptop computer. J Power Sources. 2006, 162, 532–540. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, K. N.; Azam, A. M. I. N.; Isahak, W. N. R. W.; Zainoodin, A. M.; Masdar, M. S. Improving the electrocatalytic activity for formic acid oxidation of bimetallic Ir–Zn nanoparticles decorated on graphene nanoplatelets. Mater. Res. Express. 2020, 7, 015095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Nagar, G. A.; Delikaya, Ö.; Lauermann, I.; Roth, C. Platinum Nanostructure Tailoring for Fuel Cell Applications Using Levitated Water Droplets as Green. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019, 11, 22398–22407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X. W.; Manthiram, A. Catalyst-selective, scalable membraneless alkaline direct formate fuel cells. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2015, 165, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwitonze, N.; Chen, Y. The study of Pt and Pd based anode catalysis for formic acid fuel cell, Chem. Sci. J. 2017, 8, 167. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman, S.J.; González-Cobos, J.; Giancola, S.; Sánchez-Molina, I.; Galán-Mascarós, J.R. Benchmarking Catalysts for Formic Acid/Formate Electrooxidation. Molecules. 2021, 26, 4756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Z.; Chen, W. Recent advances in formic acid electro-oxidation: from the fundamental mechanism to electrocatalysts. Nanoscale Adv. 2021, 3, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. F.; Liu, Z. P. Formic acid oxidation at Pt/H2O interface from periodic DFT calculations integrated with a continuum solvation model. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2009, 113, 17502–17508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrii, O. A. The Progress in Understanding the Mechanisms of Methanol and Formic Acid Electrooxidation on Platinum Group Metals (a Review). Russian Journal of Electrochem. 2019, 55, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Meng, Q.; Wang, X.; Jin, Z.; Liu, C.; Ge, J.; Xing, X. A new pathway for formic acid electro-oxidation: The electro-chemically decomposed hydrogen as a reaction intermediate. Journal of Energy Chemistry. 2022, 71, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, P. N.; Lipkowski, J. Electrocatalysis. New York: Wiley-VCH, 1998.

- Miki, A.; Ye, S.; Osawa, M. Surface-enhanced IR absorption on platinum nanoparticles: an application to real-time monitoring of electrocatalytic reactions. Chem. Commun. 2002, 150, 1500–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbia, M. R.; Thiel, P. A. The interaction of formic acid with transition metal surfaces, studied in ultrahigh vacuum. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1994, 369, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuesta, A.; Cabello, G.; Gutierrez, C.; Osawa, M. Adsorbed formate: the key intermediate of the oxidation of formic acid on platinum electrodes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 20091–20095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuesta, A.; Cabello, G.; Osawa, M.; Gutierrez, C. Mechanism of the electrocatalytic oxidation of formic acid on metals. ACS Catal. 2012, 2, 728–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamon, M. J.; Briega-Martos, V.; Cuesta, A.; Herrero, E. , Insight into the role of adsorbed formate in the oxidation of formic acid from pH-dependent experiments with Pt single-crystal electrodes. J. Electroanl. Chem. 2022, 925, 116886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, A.; Briega-Martos, V.; Cuesta, A.; Herrero, E. Adsorbed Formate is the Last Common Intermediate in the Dual-Path Mechanism of the Electrooxidation of Formic Acid. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 8120–8130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-X.; Heinen, M.; Jusys, Z.; Behm, R. J. Bridge-bonded formate: active intermediate or spectator species in formic acid oxidation on a Pt film electrode. Langmuir. 2006, 22, 10399–10408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y. X.; Ye, S.; Heinen, M.; Jusys, Z.; Osawa, M.; Behm, R. J. Application of in-situ attenuated total reflection-Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy for the understanding of complex reaction mechanism and kinetics: formic acid oxidation on a Pt film elektrode at elevated temperatures. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006, 110, 9534–9544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-X.; Heinen, M.; Jusys, Z.; Behm, R. J. Kinetic isotope effects in complex reaction networks: formic acid electrooxidation. Chem., Phys. Chem. 2007, 8, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Yuan, D. F.; Yang, F.; Mei, D.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.-X. On the mechanism of the direct path way formic acid oxidation at Pt(111) electrodes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 4367–4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, H.; Numata, Y.; Gojuki, T.; Mukouyama, Y. Different behavior of adsorbed bridgebonded formate from that of current in the oxidation of formic acid on platinum. Electrochim. Acta. 2014, 116, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haan, J. L.; . Masel, R. T. The influence of solution pH on rates of an electrocatalytic reactions: Formic acid electrooxidation on platinum and palladium. Electrochim. Acta. 2009, 54, 4073–4078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, J.; Uchida, T.; Cuesta, A.; Koper, M. T. M.; Osawa, M. Importance of acid-base equilibrium in electrocatalytic oxidation of formic acid on platinum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 9991–9994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perales-Rondon, J. V.; Herrero, E.; Feliu, J. M. Effects of the anion adsorption and pH on the formic acid oxidation reaction on Pt(111) electrodes. Electrochim. Acta. 2014, 140, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perales-Rondon, J. V.; Brimaud, S.; Solla-Gullon, J.; Herrero, E.; Behm, R. J.; Feliu, J. M. Further insights into the formic acid oxidation mechanism on platinum: pH and anion adsorption effects. Electrochim. Acta. 2015, 180, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, J.; Choun, N.; Jeong, J.; Lee, J. Influence of solution pH on Pt anodic catalyst in direct formic acid fuel cells. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 6848–6851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrum, I. T.; Janik, M. J. pH and alkali cation effects in the Pt cyclic voltammogram explained using density functional theory. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2016, 120, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, A.; Hermann, J. M.; Kibler, L. A. Electrocatalytic oxidation of formate and formic acid on platinum and gold: study of pH dependence with phosphate buffers. Electrocatalysis. 2017, 8, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.-K.; Wei, Z.; Chen, W.; Xu, M.-L.; Cai, J.; Chen, Y.-X. Bell shape vs volcano shape pH dependent kinetics of the electrochemical oxidation of formic acid and formate, intrinsic kinetics or local pH shift? Electrochim. Acta. 2020, 363, 13716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, J.; Uchida, T.; Cuesta, A.; Koper, M. T. M.; Osawa, M. The effect of pH on the electrocatalytic oxidation of formic acid/formate on platinum: A mechanistic study by surface-enhanced infrared spectroscopy coupled with cyclic voltammetry. Electrochim. Acta. 2014, 129, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Zuo, K. Q.; Zhengda, H.; Chen, W.; Lin, C. H.; Cai, J.; Sartin, M.; Chen, Y.-X. The mechanisms of HCOOH/HCOO– oxidation on Pt electrodes: Implication from pH effect and H/D kinetic izotope effect. Electrochem. Commun. 2017, 81, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buso-Rogero, C.; Ferre-Vilaplana, A.; Herrero, E.; Feliu, J. M. The role of formic acid/formate equilibria in the oxidation of formic acid on Pt (111). Electrochem. Commun. 2019, 98, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Scott, J.; Wieckowski, A. Direct evidence of triple-path mechanism of formate electrooxidation on Pt black in alkaline media at varying temperature. Part I: The electrochemical studies. Electrochim. Acta. 2013, 104, 124–133. [Google Scholar]

- Brimaud, S.; Solla-Gullon, J.; Weber, I.; Feliu, J. M.; Behm, R. J. Formic acid electrooxidation on noble-metal electrodes: role and mechanistic implication of pH, surface structure, and anion adsorption. ChemElectroChem, 2014, 1, 1075–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferre-Vilaplana, A.; Perales-Rondóon, J. V.; Buso-Rogero, C.; Feliu, J. M.; Herrero, E. Formic acid oxidation on platinum electrodes:a detailed mechanism supported by experiments and calculations on well-defined surfaces. J. Mater. Chem. A, 2017, 5, 21773–21784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Themsirimongkon, S.; Pongpichayakul, N.; Fang, L.; Jakmunee, J.; Saipanya, S. New catalytic designs of Pt on carbon nanotube-nickel-carbon black for enhancement of methanol and formic acid oxidation. J. of Electroanalyt Chem. 2020, 876, 114518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, M.; Zhang, J.; Luo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Ji.; Fan, J.; Wang, G.; Wang, R. Facile synthesis and enhanced catalytic activity of electrochemically dealloyed platinum–nickel nanoparticles towards formic acid electro-oxidation. J. Energy Chem. 2019, 35, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.-W.; Zhang, Z.-C.; Liao, H.-G.; Gong, Y.; Gu, L.; Qu, X.-M.; You, L.-X.; Liu, S.; Huang, L.; Tian, X.-C.; Huang, R.; Zhu, F.-C.; Liu, T.; Jiang, Y.-X.; Zhou, Z.-Y.; Sun, S.-G. Tuning Pt-skin to Ni-rich surface of Pt3Ni catalysts supported on porous carbon for enhanced oxygenreduction reaction and formic electro-oxidation. Nano Energy. 2016, 19, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, A.; Ruan, L.; Liu, B.; Chen, W.; Lin, S.; Chen, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, L. H.; Chen, B. H. Ultra-low Au decorated PtNi alloy nanoparticles on carbon for high-efficiency electro-oxidation of methanol and formic acid. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2020, 45, 22893–22905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perales-Rondón, J. V.; Ferre-Vilaplana, A.; Feliu, J. M.; Herrero, E. Oxidation mechanism of formic acid on the bismuth adatom-modified Pt (111) surface. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 13110–13113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.; Ahn, C.-Y.; Lee, H.; Kim, J. K.; Oh, S.-H.; Hwang, W.; Yang, S.; Kim, J.; Kim, O.-H.; Choi, I.; Sung, Y.-E.; Cho, Y.-H.; Rhee, C. K.; Shin, W. Bi-modified Pt supported on carbon black as electro-oxidation catalyst for 300 W formic acid fuel cell stack. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental. 2019, 253, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. Y.; Yu, Z.-Y.; Li, G.; Song, Q.-T.; Li, G.; Luo, C.-X.; Yin, S.-H.; Lu, B.-A.; Xiao, C.; Xu, B.-B.; Zhou, Z.-Y.; Tian, T.; Sun, S.-G. ; Intermetallic PtBi Nanoplates with High Catalytic Activity towards Electrooxidation of Formic Acid and Glycerol. ChemElectroChem. 2020, 7, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Qiao, M.; Huang, Y.; Zou, Y.; Liu, Z.; Tao, L.; Li, Y.; Dong, C. L.; Wang, S. In Situ Exfoliation and Pt Deposition of Antimonene for Formic Acid Oxidation via a Predominant Dehydrogenation Pathway. Research. 2020, 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawy, E. N. E.; Pickup, P. G. Carbon monoxide and formic acid oxidation at Rh@Pt nanoparticles. Electrochimi. Acta. 2019, 302, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Nagar, G. A.; Mohammad, A. M.; El-Deab, M. S.; El-Anadouli, B. E. Electrocatalysis of Formic Acid Electro-Oxidation at Platinum Nanoparticles Modified Surfaces with Nickel and Cobalt Oxides Nanostructured. Progress in Clean Energy. 2015, 1, 577–594. [Google Scholar]

- El-Nagar, G. A.; Mohammad, A. M. Enhanced electrocatalytic activity and stability ofplatinum, gold, and nickel oxide nanoparticlesbased ternary catalyst for formic acid electro-oxidation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2014, 39, 11955–11962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, A. M.; El-Nagar, G. A.; Al-Akraa, I. M; El-Deab, M. S.; El-Anadouli, B. E. Towards improving the catalytic activity and stability of platinum-based anodes in direct formic acid fuel cells. Hydrogen Energy. 2015, 40, 7808–7816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Refaei, S. M.; El-Nagar, G. A.; Mohammad, A. M.; El-Deab, M. S.; El-Anadouli, B. E. Electrocatalytic Activity of NiOx Nanostructured Modified Electrodes Towards Oxidation of Small Organic Molecules. In book: 2nd International Congress on Energy Efficiency and Energy Related Materials (ENEFM2014). 2015, 1-7.

- El-Nagar, G. A Mohammad, A. M.; El-Deab, M. S.; El-Anadouli, B. E. Propitious Dendritic Cu2O−Pt Nanostructured Anodes for Direct Formic Acid Fuel Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017, 9, 19766–19772. [Google Scholar]

- Ali Al-Qodami, B.; Farrag, H. H.; Sayed, S. Y.; Allam, N. K.; El-Anadouli, B. E.; Mohammad, A. M. Bifunctional Tailoring of Platinum Surfaces with Earth Abundant Iron Oxide Nanowires for Boosted Formic Acid Electro-Oxidation. Journal of Nanotechnology. 2018, 2018, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, A. M.; Al-Akraa, I. M.; El-Deab, M. S. Superior electrocatalysis of formic acid electrooxidation on a platinum, gold and manganese oxide nanoparticle-based ternary catalyst. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2018, 43, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asal, Y. M.; Al-Akraa, I. M.; Mohammad, A. M.; El-Deab, M. S. A competent simultaneously co-electrodeposited Pt-MnOx nanocatalyst for enhanced formic acid electro-oxidation. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Engineers. 2019, 96, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Nagar, G. A.; Mohammad, A. M.; El-Deab, M. S.; El-Anadouli, B. E. Facilitated electrooxidation of formic acid at nickel oxide nanoparticles modified electrodes. J Electrochem Soc. 2012, 159, F249–F254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Nagar, G. A.; Mohammad, A. M.; El-Deab, M. S.; El-Anadouli, B. E. Electrocatalysis by design: enhanced electrooxidation of formic acid at platinum nanoparticles–nickel oxide nanoparticles binary catalysts. Electrochim Acta. 2013, 94, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caglar, A.; Cogenli, M. S.; Yurtcan, A. B.; Kivrak, H. Effective carbon nanotube supported metal (M=Au, Ag, Co, Mn, Ni, V, Zn) core Pd shell bimetallic anode catalysts for formic acid fuel cells. Renewable Energy. 2020, 150, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Yan, B.; Li, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Guo, J.; Du, Y. N-doped graphene supported PtAu/Pt intermetallic core/dendritic shell nanocrystals for efficient electrocatalytic oxidation of formic acid. Chem Eng J. 2018, 334, 2638–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Akraa, I. M.; Salama, A. E.; Asal, Y. M.; Mohammad, A. M. Boosted performance of NiOx/Pt nanocatalyst for the electro-oxidation of formic acid: A substrate’s functionalization with multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Arabian Journal of Chemistry. 2021, 14, 103383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saquib, M.; Halder, A. Ensemble Effect of Ni in Bimetallic PtNi on Reduced Graphene Oxide Support for Temperature-Dependent Formic Acid Oxidation. ChemistrySelect. 2018, 3, 3909–3917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatla, A. S.; Hassan, K. M.; Abd-El-Latif, A. A.; Hathoot, A. A.; Baltruschat, H.; Abdel-Azzem, M. Poly 1,5 diaminonaphthalene supported Pt, Pd, Pt/Pd and Pd/Pt nanoparticles for direct formic acid oxidation. J. Electroanalyt. Chemistry. 2019, 833, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Moghny, M. G. A.; Alalawy, H. H.; Mohammad, A. M.; Mazhar, A. A.; El-Deab, M. S.; El-Anadouli, B. E. Conducting polymers inducing catalysis: Enhanced formic acid electro-oxidation at a Pt/polyaniline nanocatalyst. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2017, 42, 11166–11176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Dimitrov, N. Ultralow Pt loading nanoporous Au-Cu-Pt thin film as highly active and durable catalyst for formic acid oxidation. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental. 2020, 263, 118366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.-J.; Xu, H. T.; Li, X.; Wang, J. Q.; Wang, Y. Core–shell-structured nanoporous PtCu with high Cu content and enhanced catalytic performance. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2015, 3, 7939–7944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Yan, X.; Ren, W.; Jia, Y.; Chen, J.; Sun, D.; Xu, L.; Tang, Y. Porous AgPt@Pt Nanooctahedra as an Efficient Catalyst toward Formic Acid Oxidation with Predominant Dehydrogenation Pathway. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016, 8, 31076–31082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, J.; Wei, X.; Luo, R.; Wang, G.; Wang, R. Dealloyed platinum-copper with isolated Pt atom surface: Facile synthesis and promoted dehydrogenation pathway of formic acid electro-oxidation. J Electroanal Chem. 2017, 799, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Meng, F.; Wang, H.; Jiang, X.; Zhu, Y. Nanoporous AuPt alloy with low Pt content: a remarkable electrocatalyst with enhanced activity towards formic acid electro-oxidation. Electrochim. Acta. 2016, 190, 852–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.-H.; Liu, H.-M.; Bai, J.; Tian, X. L.; Xia, B. Y.; Zeng, J.-H.; Jiang, J.-X.; Chen, Y. Platinum-silver alloy nanoballoon nanoassemblies with super catalytic activity for the formate electrooxidation. ACS Appl Energy Mater. 2018, 1, 1252–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, F.; Jin, Y.; Guo, L.; Gong, X.; Wanga, X.; Johnston, R. L. In situ high-potential-driven surface restructuring of ternary AgPd–Ptdilute aerogels with record-high performance improvement for formate oxidation electrocatalysis. Nanoscale. 2019, 11, 14174–14185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nacys, A.; Balčiūnaitė, A.; Zabielaitė, A.; Upskuvienė, D.; Šebeka, B.; Jasulaitienė, V.; Kovalevskij, V.; Šimkūnaitė, D.; Norkus, E.; Tamašauskaitė-Tamašiūunaitė, L. An Enhanced Oxidation of Formate on PtNi/Ni Foam Catalyst in an Alkaline Medium. Crystals, 2022, 12, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, D.; Seah, M. P. Practical Surface Analysis, John Wiley & Sons. 1993, 1.

- Kim, K. S.; Winograd, N. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopic studies of nickel oxygen surfaces using oxygen and argon ion-bombardment. Surf. Sci. 1974, 43, 625–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittstok, G.; Strübing, A.; Szargan, R.; Werner, G. Glucose oxidation at bismuth-modified platinum electrodes. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1998, 444, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasini, D. R.; Rochefort, D.; Fachini, E.; Aldena, L. R.; DiSalvo, F. J.; Cabrera, C. R.; Abruna, H. D. Surface composition of ordered intermetallic compounds PtBi and PtPb. Surf. Sci., 2006, 600, 2670–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanli, A. E.; Aytaç, A. Electrochemistry of The Nickel Electrode as a Cathode Catalyst In The Media Of Acidic Peroxide For Application of The Peroxide Fuel Cell. ECS Transactions. 2012, 42, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiler, K.; Krawiec, H.; Kozina, I.; Sort, J.; Pellicer, E. Electrochemical characterisation of multifunctional electrocatalytic mesoporous Ni-Pt thin films in alkaline and acidic media. Electroch. Acta, 2020, 359, 136952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trasatti, S.; Petrii, O. A. Real surface area measurements in electrochemistry. Pure Appl. Chem. 1991, 63, 711–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samjeské, G.; Miki, A.; Ye, S.; Osawa, M. Mechanistic Study of Electrocatalytic Oxidation of Formic Acid at Platinum in Acidic Solution by Time-Resolved Surface-Enhanced Infrared Absorption Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006, 110, 16559–16566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemos, S. G.; Oliveira, R. T. S.; Santos, M. C.; Nascente, P. A. P.; Bulhões, L. O. S.; Pereira, E. C. Electrocatalysis of methanol, ethanol and formic acid using a Ru/Pt metallic bilayer. J. Power Sources. 2007, 163, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, R. S.; Shain, I. Theory of Stationary Electrode Polarography. Single Scan and Cyclic Methods Applied to Reversible, Irreversible, and Kinetic Systems. Analytical Chemistry. 1964, 36, 706–723. [Google Scholar]

- Çögenli, M.S.; Yurtcan, A.B. Catalytic activity, stability and impedance behavior of PtRu/C, PtPd/C and PtSn/C bimetallic catalysts toward methanol and formic acid oxidation. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 2018, 43, 10698–10709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Akraa, I.M.; Mohammad, A.M. A spin-coated TiOx/Pt nanolayered anodic catalyst for the direct formic acid fuel cells. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 4703–4711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Akraa, I.M.; Asal, Y.M.; Darwish, S.A. A simple and effective way to overcome carbon monoxide poisoning of platinum surfaces in direct formic acid fuel cells. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2019, 14, 8267–8275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Huang, B.; Li, Y.; Qin, Y.; Fu, Z.; Sun, M.; Wang, L.; Guo, S. Segmented Au/PtCo heterojunction nanowires for efficient formic acid oxidation catalysis. Fun. Res. 2021, 1, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| cFA, M | Peak I | Peak II | Peak III | Peak IV | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epc, V |

jd, mA cm-2 |

Epc, V |

jind, mA cm-2 |

jd/jind | Epc, V |

jd, mA cm-2 |

Epc, V |

jb, mA cm-2 |

(jd)/(jb) | |

| 0.3 0.5 0.7 |

0.320 | 0.42 | 0.661 | 2.29 | 0.18 | 1.227 | 2.54 | 0.390 | 6.30 | 0.07 |

| 0.319 | 0.45 | 0.671 | 3.10 | 0.14 | 1.236 | 3.43 | 0.391 | 9.37 | 0.05 | |

| 0.327 | 0.44 | 0.679 | 3.64 | 0.12 | 1.234 | 4.29 | 0.405 | 12.00 | 0.04 | |

| cFA, M | Peak I | Peak II | Peak IV | Peak V | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epc, V |

jd, mA cm-2 |

Epc, V |

jind, mA cm-2 |

jd/jind | Epc, V |

jd, mA cm-2 |

Epc, V |

jb, mA cm-2 |

(jd)/(jb) | |

| 0.05 0.07 0.1 0.3 0.5 0.7 |

0.426 | 9.47 | 0.618 | 9.70 | 0.98 | 0.326 | 14.52 | 0.086 | 8.865 | 0.65 |

| 0.439 | 23.18 | 0.615 | 20.27 | 1.14 | 0.393 | 34.14 | 0.249 | 25.740 | 0.68 | |

| 0.456 0.549 0.390 0.390 |

28.01 75.10 21.71 18.90 |

0.680 0.821 0.870 0.949 |

28.14 100.80 164.55 263.10 |

1.00 0.75 0.13 0.07 |

0.441 0.508 0.556 0.603 |

55.75 145.30 223.55 261.50 |

0.297 |

38.565 |

0.50 0.52 0.10 0.07 |

|

| Catalyst | I d /Iind | Conditions of Experiment | pH | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NiOx/Pt/GC | 0.33 | 0.3 M FA,pH 3.5, 100 mV/s |

3.5 | [69] |

| NiOx/Pt/CNTs/GC | ∝ | 0.3 M FA, pH 3.5, 100 mV/s |

3.5 | [69] |

| Pt/GC | 0.69 | 0.3 M FA, pH 3.5, 100 mV/s |

3.5 | [69] |

| Commercial Pt/C | 0.16 | 0.5 M FA + 0.1M HClO4, pH ≈1.0 50 mV/s |

1.0 | [51] |

| Pt11.1Ni88.9/C | 0.33 | 0.5 M FA + 0.1M HClO4, pH ≈1.0 50 mV/s |

1.0 | [51] |

| Pt10.9 Au0.2Ni88.9/C | 0.34 | 0.5 M FA + 0.1M HClO4, pH ≈1.0 50 mV/s |

1.0 | [51] |

| Pt/C | 0.29 | 0. 5 M FA + 0.5 M H2SO4 , pH 0.3 50 mV s |

0.3 | [91] |

| Pt black | 0.24 | 0. 5 M FA + 0.5 M H2SO4, pH 0.3, 50 mV s |

0.3 | [91] |

| PtPd/C | 0.87 | 0. 5 M FA + 0.5 M H2SO4, pH 0.3, 20 mV s |

0.3 | [91] |

| Pt-TiOx (700 C) | 10.00 | 0.3 M FA, pH = 3.5, 100 mV/s |

3.5 | [92] |

| Pt/MWCNTs-GC | 7.50 | 0.3 M FA, pH = 3.5, 100 mV/s |

3.5 | [93] |

| MnOx/Au/Pt/GC | 30.20 | 0.3 M FA , pH ≈ 3.5 + a proper amount of NaOH, 100 mV/s |

3.5 | [63] |

| NiOx/Au/Pt/GC | ∝ | 0.3 M FA , pH = 3.5 +a proper amount of NaOH, 100 mV/s |

3.5 | [59] |

| nano-NiOx/Pt | 50.00 | 0.3 M FA , pH = 3.5 +a proper amount of NaOH, 100 mV/s |

3.5 | [65] |

| nano-NiOx/Pt/GC | 17.00 | 0.3 M FA , pH = 3.5 +a proper amount of NaOH, 100 mV/s |

3.5 | [66] |

| Au23/Pt63Co14 | 3.60 | 0.5 M FA + 0.1 M HClO4 pH ≈ 1.0, 50 mV/s |

1.0 | [94] |

| PtNi/Nifoam | 1.14 | 0.07 M FA + 0.5 M H2SO4 , pH 0.3, 50 mV/s |

0.3 | This work |

| PtNi/Nifoam | 1.00 | 0.1 M FA + 0.5 M H2SO4 , pH 0.3, 50 mV/s |

0.3 | This work |

| PtNi/Nifoam | 0.70 | 0.3 M FA + 0.5 M H2SO4 , pH 0.3, 50 mV/s |

0.3 | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).