Introduction

The ongoing first global outbreak of the mpox virus in humans (formerly known as monkeypox) was first recognized in May 2022 when several countries in Europe and North America, where the disease was not endemic, declared the first mpox cases [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. The World Health Organization declared the infection a public health emergency of international concern on July 23, 2022 [

7]. As of August 29, 2023, over 89000 laboratory-confirmed cases have been reported worldwide from 114 Member States across all 6 WHO regions, with over 26,000 cases in the European Region [

8].

Mpox is a zoonotic disease caused by a double-stranded DNA virus classified in the Orthopoxvirus genus of the Poxviridae family. The disease is endemic to western and central Africa, especially in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Transmission before 2022 was predominantly zoonotic, related to direct contact with infected animals. Most cases detected outside the endemic areas responded to sporadic and limited outbreaks linked to exotic pet trade or travel activity [

9]. During the current global outbreak, the transmission has occurred through close person-to-person contact, predominantly sexual contact through high-risk sexual practices, without epidemiological links to western or central Africa and mainly, but not exclusively, in men who have sex with men (MSM) [

8]. HIV infection has been overrepresented in the current outbreak, with approximately 40-50% of the cases being co-infected with HIV[

10]. The illness is usually mild symptomatic, including few skin- and/or mucosal lesions at inoculation sites, fever and local lymphadenopathy, and 15-30% present with proctitis [

10,

11]. However, more severe cases have been described, especially in immunosuppressed patients, e.g., HIV-related immunosuppression, with necrotizing skin lesions, lung involvement, central nervous system infection, secondary bacterial infections, sepsis and ocular involvement [

12]. As of August 129, 2023, a total of 157 deaths have been reported globally, which underscores that mpox can be a life-threatening disease in an immunosuppressed host and that ongoing measures are needed to prevent infection and disease spread [

8].

The earlier vaccinia virus vaccination administered against smallpox provided cross-immunity to mpox virus as both viruses are closely related to Orthopoxviruses. Discontinuation of routine smallpox vaccination following smallpox eradication in the early 1980s and thus waning immunity with no immunity coverage in the population <40 years of age has probably been an important risk factor for the current emergence of mpox as a public health thread [

9].

The objective of this study is to describe the epidemiological data collected during the outbreak in Catalonia in 2022, as part of the public health surveillance program with special focus on the differences in clinical outcomes at a population level between people with HIV (PWH) and without HIV (PWoH), and in those with severe immunosuppression among PWH. Furthermore, we aim to explore the efficacy of dose-sparing smallpox vaccination, which was implemented at the beginning of the outbreak due to restrained vaccine availability, in controlling the outbreak.

Material and Method

Setting

On January 1, 2023, Catalonia had a population of 7∙7 million citizens and an estimated HIV prevalence among the adult population of 0∙4%. The Catalan healthcare system provides universal, tax-funded healthcare and antiretroviral therapy, mpox test, mpox vaccination and mpox treatment are provided free-of-charge to all citizens.

Mpox is a nationally notifiable disease in Spain and mpox cases are notified by sexually transmitted infections (STIs) clinics, primary healthcare and hospitals to the Surveillance System of the Regional Ministry of Health. Data are collected using standardized case report forms (CRF).

Study Design and Data Sources

This is a surveillance study conducted in Catalonia, Spain, including all confirmed cases of mpox between May 06 and December 19, 2022. A confirmed mpox case was defined as a positive laboratory result of mpox virus polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Specimens were collected from suspected lesions for each suspected case. Laboratory analyses were conducted in the National Reference Laboratory in Madrid until May 31, 2022. From this date forward, the mpox testing capacity was enhanced and was available in 12 different laboratories in Catalonia.

Data collection was performed by trained epidemiologists who completed the mpox standardized CRFs. We linked this surveillance data with the Catalan HIV PISCIS cohort (Catalonian and Balearic Islands HIV cohort) and PADRIS (Public Data Analysis for Health Research and Innovation Program).

The study design of PISCIS is described elsewhere[

13]. Briefly, PISCIS is an ongoing, prospective, multicentre, population-based cohort from 1998 that includes all PWH aged ≥16 years followed in one of the 16 collaborating hospitals in Catalonia, representing 84% of all diagnosed PWH. Data are updated yearly and include demographics, date of HIV diagnosis, AIDS-defining events, antiretroviral therapy, and measurement of CD4

+T-cell count and plasma HIV-RNA over time.

PADRIS is a research-oriented big data repository, which gathers and crossmatches real-world health data generated by the public health care system of Catalonia (SISCAT). Programmatic Health data is provided by the Catalan Agency for Health Quality and Evaluation (AQuAS). The registry includes individual-level comorbidity data from hospital discharge diagnoses and primary health care from 2005 according to the International Classification of Disease 10

th revision (ICD-10), laboratory, microbiology, prescription and epidemiological surveillance data from mandatory notification systems of infectious diseases [

14]. From PADRIS we retrieved information for other notifiable sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and comorbidity data using ICD-10 codes, defining comorbidities according to the Swedish National Study of Aging and Care in Kungsholmen (SNAC-K) cohort (

www.snac-k.se) (eTable 1,2).

Charlson comorbidity scores at baseline were calculated in all groups using diagnosis coded in PADRIS, excluding AIDS-defining event, which was assessed separately [

15].

Study Population

We included all individuals with laboratory confirmed mpox between May 06 and December 19, 2022.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were described as the median and the interquartile range (IQR), whereas categorical variables were presented as the frequency and percentage of available data. We used the chi-squared, T, and Mann-Whitney U tests to compare variables between the groups.

We conducted descriptive statistics on demographics and clinical outcomes comparing PWoH and PWH individuals. We described also the prevalence of other concomitant STIs at mpox diagnosis (with a time window of 8 weeks either side of mpox diagnosis) and in the 2-year period before mpox.

Descriptive statistics were also conducted in the group of PWH, comparing those with CD4+T-cell counts <200 and ≥200 cells/µL at mpox diagnosis.

We constructed an epidemiological curve with the aggregated confirmed cases of mpox per week to explore the temporal relation with the initiation of dose-sparing smallpox vaccination in Catalonia. We used negative binomial regression to assess the impact of vaccination on the daily counts of mpox cases and provided p-value as significance test.

We used STATA software for the analysis (v.16; Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethics Approval

The PISCIS cohort has received ethical approval from Germans Trias i Pujol University Hospital’s Clinical Research Ethics Committee, reference number EO-11-108, and patient data extraction is allowed by the 203/2015 Decree from the Catalan Health Department. All data are pseudo-anonymized in accordance with Regulation 2016/679 of the European Parliament.

Results

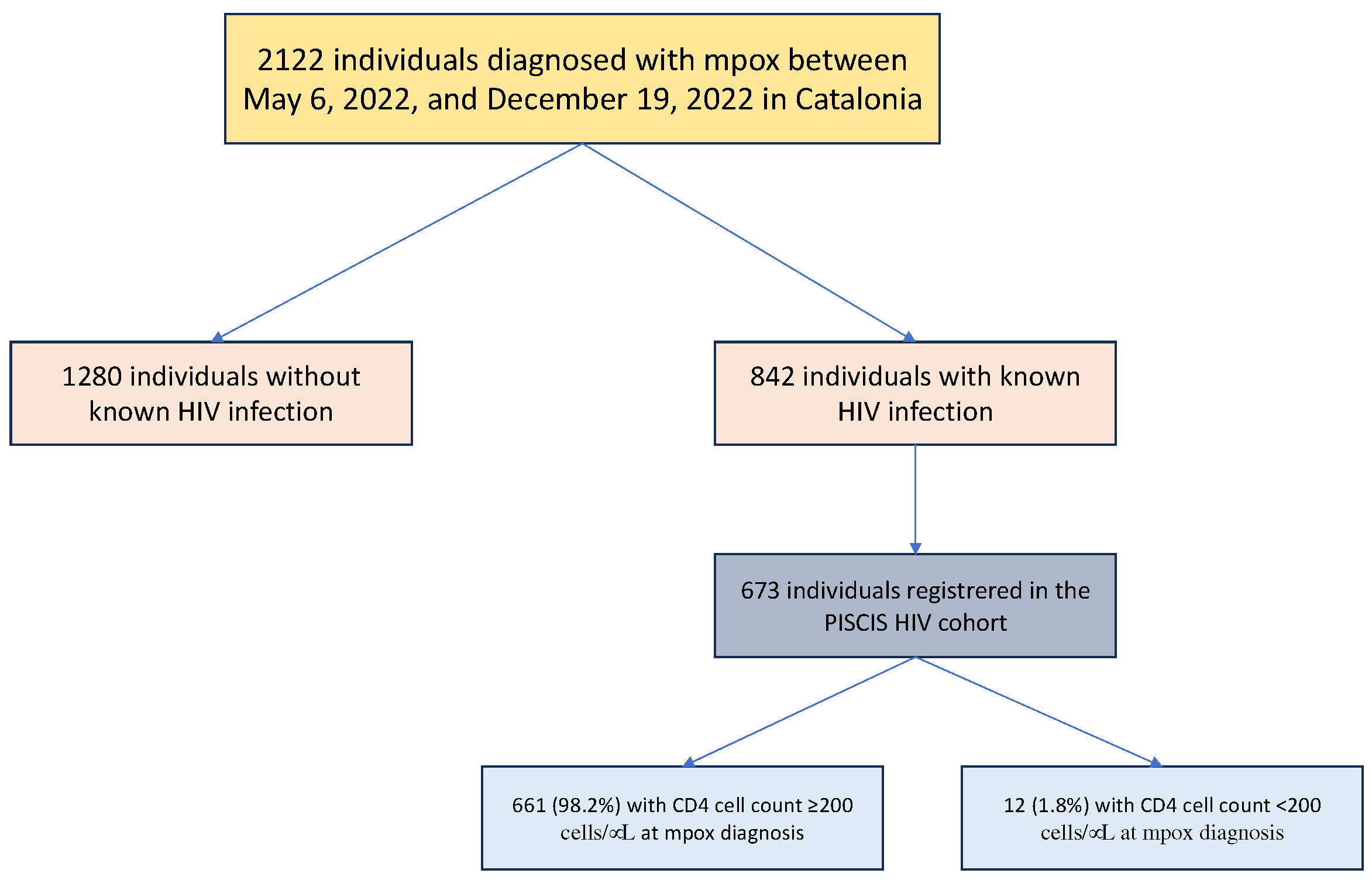

A total of 2122 individuals were reported with confirmed mpox during the study period. Of these, 842 (39.7%) had HIV-coinfection (

Figure 1). Overall, the most probable reported transmission mode of mpox was sexual (88.2%), in men (97.6%), with a median age at mpox diagnosis of 38 years (IQR: 32-44). Fifty-nine percent were of Spanish origin, 21% from South America, 13% from other European countries, and the rest from different countries around the word. Approximately 9% had travelled internationally in the 3 weeks prior to mpox diagnosis.

The clinical characteristics of PWoH and PWH are shown in

Table 1. Most individuals were symptomatic with a mild and self-limiting disease. The symptoms were similar in the PWoH and PWH groups, except the latter had more frequent fever, headache and generalized exanthema (p=0.015, 0.023, and 0.002, respectively). The rash was described mainly as maculopapular, vesicular, umbilical or pustular, the two latter more commonly described among PWH (p=0.011). The complication rate (bacterial skin infections, pneumonia, cornea infection, proctitis and/or hospitalization requirement) was low overall (5.0%), without significant differences in both groups (p=0.13). Approximately 2% of the patients developed bacterial superinfection of the skin lesion, mainly in the anogenital region followed by the facial area, and 1.4% developed proctitis. Only 2 patients developed pneumonia and 3 corneal infections, both in the PWH group. Forty-four (2.1%) individuals required hospital admission, without differences in the two groups (p=0.16). No severe complications (sepsis, encephalitis, myocarditis) were observed except one unvaccinated PWoH who required admission to the intensive care unit (ICU). There were no mpox-related deaths in this series.

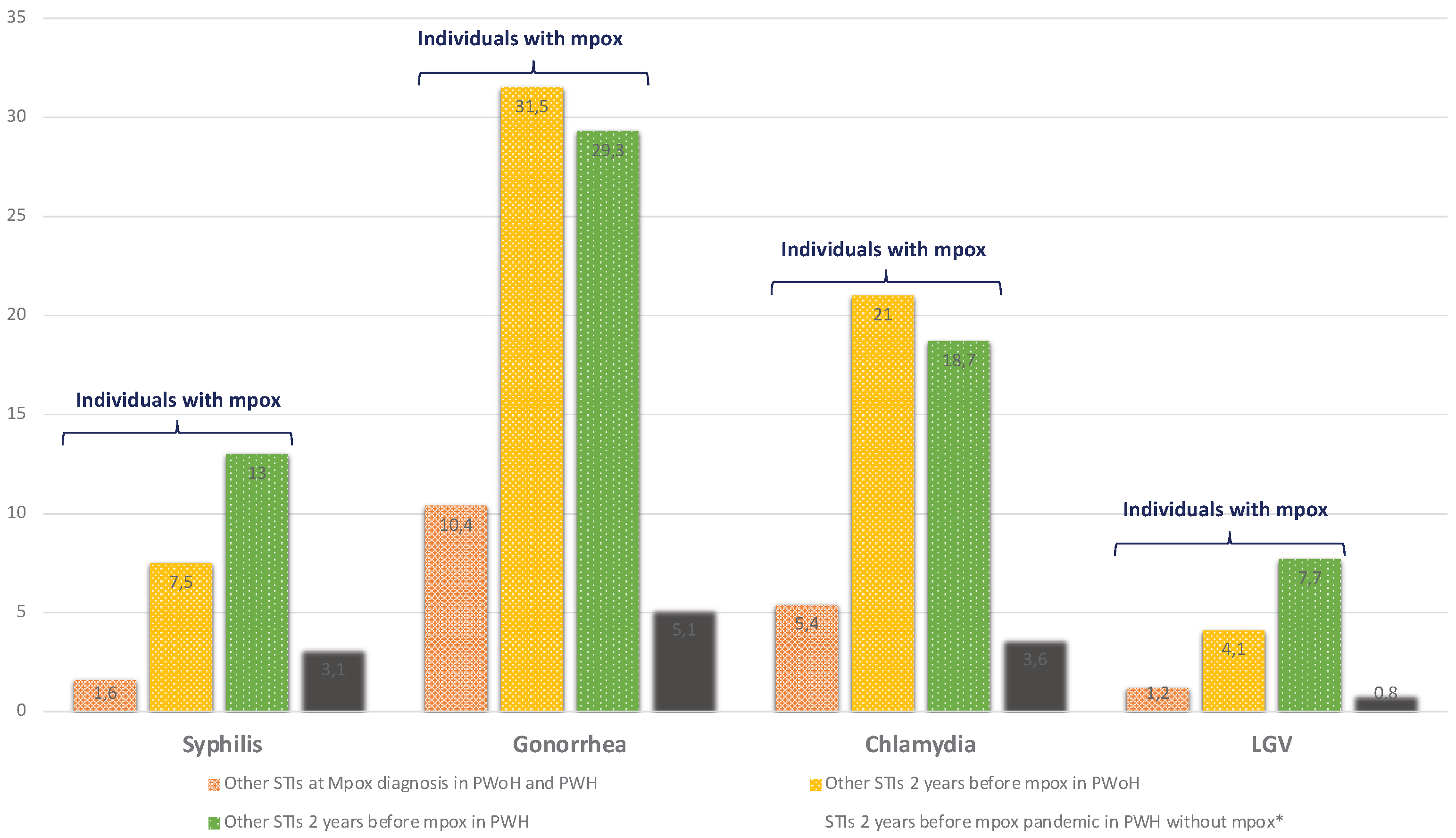

Overall, 16.5% of mpox cases were diagnosed with a concomitant notifiable STI at mpox diagnosis and 43% had had at least one notifiable STI in the two years before mpox compared to 8.5% of PWH without mpox (p<0.0001) (

Figure 2, etable 3).

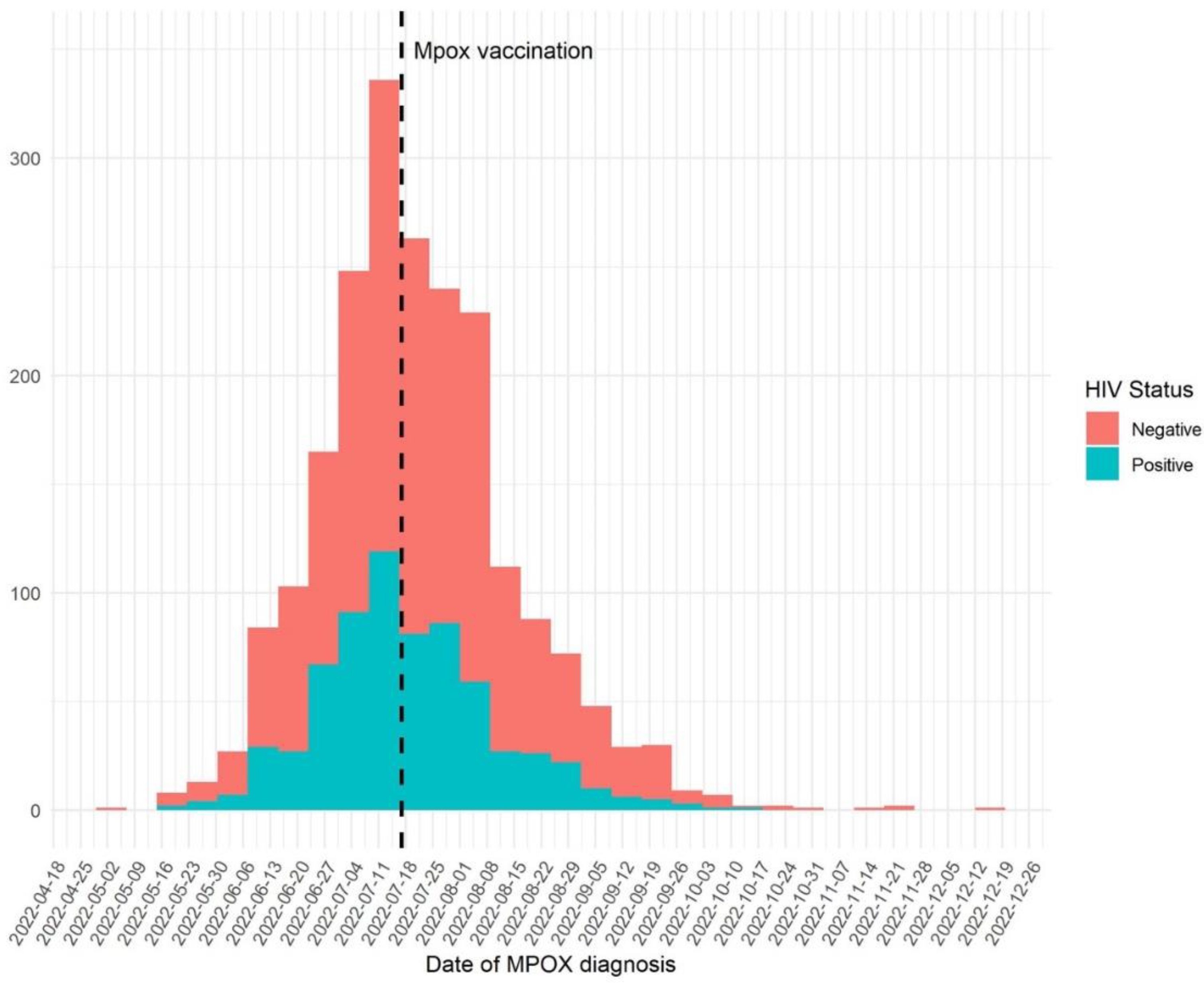

Smallpox vaccination was introduced in Catalonia on July 17, 2022, and was associated with a statistically significant decline in the mpox incidence as shown in

Figure 3 (p<0.0001).

At mpox diagnosis, 23.7% and 14.5% (p<0.0001) of PWH and PWoH had received at least one fractioned dose of the smallpox vaccine during the outbreak, with a median time from the first dose of the vaccine to the development of the symptoms of 23 days (IQR: 13-48)

A higher percentage of PWH (16.5%) compared to PWoH (8.4%) had received smallpox vaccination in childhood (p<0.0001).

PWH developing mpox were mainly men (99.7%), MSM (92.3%) with a median age of 41 years (IQR 35-46). The median CD4+T-cell count at mpox diagnosis was 715 cells/µL (IQR 526-909) with only 12 (1.8%) individuals with CD4+T-cell count <200 cells/μL. Eighty-three percent of PWH had plasma HIV-RNA <50 copies/mL at mpox diagnosis, 66.7% in the group of individuals with CD4+T-cell count <200 cells/μL (p=0.12).

We compared the clinical presentation of mpox in the 673 PWH included in the PISCIS cohort with CD4+T-cell count <200 versus ≥200 cells/µL (

Table 2). The median CD4+T-cell count was 122 cells/µL (IQR 72-176) and 724 cells/µL (IQR 540-912), respectively. The Charlson comorbidity scores were similar in both groups, with more than ¾ having an index of 0. However, malignancy and earlier AIDS-defining events were more common in PWH with CD4+T-cell count <200 cells/μL (25% versus 5.8%, p=0.006 and 33.3% versus 7.7%, p=0.001, respectively). Furthermore, we found that PWH with CD4+T-cell count <200 cells/μL were more commonly from Latin America (100% versus 41%, p<0.0001), had more generalized exanthema (83.3% versus 44.6%, p=0.008), had more frequent pustular and haemorrhagic exanthema (50.0% versus 20.6%, p=0.013 and 8.3% versus 0.3%, p<0.0001, respectively) and required more frequently hospitalization (16.7% versus 2%, p=0.001). However, no individual required hospitalization in ICU, and no severe complications, such as pneumonia, bacterial infection or proctitis, were recorded.

Discussion

We report population surveillance data on 2122 mpox cases notified from May 06, 2022, to December 19, 2022, in Catalonia, in PWoH and PWH. The risk of severe mpox infection or hospitalization was not increased in PWH compared to PWoH, except in immunosuppressed individuals. However, the absolute numbers of immunosuppressed PWH were very low. We found that HIV coinfection or other STIs were common among individuals diagnosed with mpox, which highlights the importance of screening for HIV and STIs in these individuals. We also observed notable disparities in mpox incidence among individuals of Latin American origin. Finally, dose-sparing smallpox vaccination was implemented at the beginning of the outbreak due to restrained vaccine availability and was associated with a significant decline in mpox cases in both groups.

Mpox infection usually had a mild course, and most individuals recovered without complications both in PWH and PWoH. The rate of severe illness was very low and although both severe disease and death have been described in other reports, we did not observe any severe complications or death cases in this series. In a recent report, the mpox-associated death rate in the US was 1.3 per 1000 cases (and 1.2 per 1000 cases worldwide), mainly observed in immunocompromised unvaccinated individuals [

16]. This case fatality rate is lower than reported in outbreaks before 2022 [

9].

Transmission during the current mpox outbreak was mainly due to sexual activity in high-risk unprotected sexual practices, mainly in MSM, as evidenced by the numerous previous and concomitant diagnoses of other notifiable STIs in these individuals and the rates of HIV co-infection. Control measures such as contact tracing, information campaigns and vaccination were pivotal and introduced early during the outbreak. Vaccination represents an important public health measure to reduce disease spread and severity and control the epidemic. The smallpox vaccine (JYNNEOS; Modified Vaccinia Ankara-Bavarian Nordic; MVA-BN) was offered against mpox during the study period in a two-dose regimen. Due to restrained vaccine availability, a dose-sparing vaccination strategy was initially implemented, fractionating a full-dose vaccine vial into five doses and promoting it to all individuals at high risk. From October 2022, a full second dose was offered to all individuals.

Although the efficacy of the vaccine against mpox has not been assessed in clinical trials, real-world studies have shown good effectiveness. A recent study from Israel evaluating 1037 male individuals who completed only the first dose of the vaccine and were followed up for at least 90 days estimated that the adjusted vaccine effectiveness in preventing infection was 86% (95% confidence interval 59-95%)[

17]. A CDC report from December 2022 estimated that the mpox incidence was 7 and 10 times higher among unvaccinated individuals compared to those who had received only one dose or both vaccine doses, respectively [

18]. In a recent study, Dimitrov et al also showed that a dose-sparing vaccination strategy was moderately effective [

19].

The smallpox vaccine became available in Catalonia on July 17, 2022, and was recommended for unvaccinated adults with a high risk of contracting the infection, that is, those who engaged in high-risk sexual activities, and for close contacts of confirmed cases who, if they were to contract the disease, had a higher risk of suffering further complications, such as children, pregnant women and immunocompromised people, if the vaccine could be administrated within four days from exposure to the infection. The introduction of the dose-sparing vaccine was associated with a clear decline in incidence in our population. However, other reasons, like the effect of other public health measures instigated, could have also played a role.

Among patients developing mpox, the rates of prior smallpox vaccination were higher in PWH, probably reflecting the recommendations for vaccination of high-risk populations at that time and their accessibility through STI and HIV Units. Interestingly, PWH also had higher rates of smallpox vaccination from childhood, which could be related to their older age and the potentially higher smallpox vaccination rates in migrants.

The prevalence of HIV coinfection among mpox cases in our population is similar to that described in the previous case series, at approximately 40% [

10,

11]. This is most likely due to the overrepresentation of people with high-risk sexual practices, as evidenced by the significant disparities in prevalence of other STIs in PWH with and without mpox in our study (p<0.0001, figure 3 and table S1). These results highlight the importance of offering HIV testing to all mpox cases and screening for other STIs. A mpox diagnosis is, therefore, an opportunity to prescribe pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), which should be considered in HIV-negative cases in order to reduce the risk of later HIV infection in this high-risk group. Besides, initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in PWH who are not yet on ART is important, especially in cases of advanced HIV infection, in order to boost immune recovery. Most PWH developing mpox had high CD4+T-cell count at mpox diagnosis and undetectable plasma HIV-RNA, reflecting a population mostly successfully treated for HIV.

Except in the case of HIV-related immunosuppression, PWH had a similar mpox clinical outcomes compared to PWoH. Nevertheless, PWH had more frequent fever, headache and generalized umbilical or pustular exanthema (p=0.015, 0.023, and 0.002, respectively). Although the absolute numbers of PWH with low CD4+T-cell count <200 cells/µL and mpox infection were very low (1.8% of all PWH with mpox), we found a more severe illness, with more generalized exanthema, with more frequently pustular and hemorrhagic pattern, and with higher rates of hospitalization. One-third of these patients had had a previous AIDS-defining event, and one-fourth had had a malignancy diagnosis, evidencing a population with severe immune suppression and a higher comorbidity burden. However, no severe complications or deaths occurred in this series. With our surveillance data, we cannot further describe the details of the clinical presentations, but in a recent report, PWH with CD4+T-cell count <100 cells/µL and unsuppressed HIV viremia were identified at higher risk of severe disease, with risk for necrotizing skin and mucosal lesions, lung involvement with multifocal opacities (perivascular nodules), secondary bacterial infection, sepsis and death [

12]. Severity in mpox has mainly been reported in PWH with low CD4+T-cell count and has been proposed to be considered an AIDS-defining event. These individuals exhibited high rates of IRIS following ART initiation, including severe IRIS with a high mortality risk. However, the rate of coinfection with other opportunistic infections in these patients was high (26%), which could have confounded the observations.

Overall, a relatively high percentage of PWH developing mpox in our series were from Latin America (42%), including 100% of the immunosuppressed PWH, which may relate to ethnic disparities in HIV infection and inequities and barriers to HIV and STI prevention and mpox information and vaccination. Similarly, the US CDC has also recently reported a disproportionately higher incidence of mpox among Hispanic and Black/African American men in the US (31% and 33%, respectively) as well as a higher risk of death, indicating important health inequities and social risk factors in these groups [

16,

20]. Other studies have shown that assortative mixing in the selection of sexual partners may play a role in the observed increased incidence of HIV and other STIs in some clusters and might also have played a role in the racial disparities observed during the mpox epidemic [

21]. It is crucial to ensure early and equal access to mpox and HIV prevention and treatment in all communities for continued control of both infections.

A strength of our study is the population-based dataset with all confirmed mpox cases reported in Catalonia, including individuals with HIV coinfection. We had access to the PISCIS cohort with data on CD4+T-cell count and HIV-RNA measurements close to the mpox diagnosis. In addition, we had access to high-quality comorbidity data in these patients and access to all notifiable STIs.

Our study has some limitations, including the surveillance nature of the data, and not having detailed clinical data for the course of hospitalization regarding complications and treatment. Furthermore, our study includes a limited number of PWH with low CD4+T-cell count and therefore at risk for severe mpox disease, and it is therefore not possible to rule out type II errors in the analysis of this subpopulation.

In conclusion, unless immunosuppressed, PWH were not at increased risk of severe mpox or hospitalization compared to PWoH. PWH had more frequent fever, headache and generalized umbilical or pustular exanthema. Mpox was associated with high rates of coinfection with HIV and other STIs and represents a marker of high-risk sexual behavior, supporting the importance of STIs and HIV testing in all mpox cases. Mpox diagnosis in HIV-negative individuals should trigger considerations to offer PrEP. We observed ethnicity disparities in mpox incidence during the outbreak, underscoring all communities' need for equal access and utilization of healthcare services for continued efforts against mpox. Finally, dose-sparing smallpox vaccination was associated with a sharp and significant decline in mpox incidence in our study.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Transparency statement

We hereby declare that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as originally planned have been explained.JMM has received consulting honoraria and/or research grants from AbbVie, Angelini, Contrafect, Cubist, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Jansen, Lysovant, Medtronic, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, and ViiV Healthcare, outside the submitted work.JML has received honoraria and/or research grants from ViiV Healthcare, Gilead Sciences and Janssen-Cilag.PAL has received honoraria from Gilead Sciences, Janssen-Cilag, MSD and ViiV Healthcare, outside the submitted work.

Contributors

RMI conducted the research and RMI, YD, LAR analysed the data. RMI and JML wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and all authors contributed to the interpretation of the results and revision of the manuscript and gave their final approval to the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients who participated in this cohort and our colleagues in the clinical departments for their continued contribution and dedication.We also want to thank PADRIS and the Programme for the Prevention, Control and Care for HIV, Sexually Transmitted Diseases and Viral Hepatitis of the Ministry of Health of the Government of Catalonia for their support and Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS) for financial support.The PISCIS study group includes: J. Casabona, A. Esteve, A. Bruguera, S. Moreno-Fornés (CEEISCAT), JM. Miró, J. Mallolas, E. Martínez, JL Blanco, M. Laguno, M. Martínez-Rebollar, B. Torres, A. Gonzalez-Cordon (Hospital Clínic-Idibaps, Universitat de Barcelona), Elisa De Lazzari (Hospital Clínic-Idibaps), Arkaitz Imaz (Unitat de VIH i ITS, Servei de Malalties Infeccioses, Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge, IDIBELL), Pere Domingo (Unitat de VIH/SIDA Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau), Josep María Llibre (Fundació Lluita contra la Sida-Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol-Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona), Francisco Fanjul (Servei Medicina Interna, Hospital Universitari Son Espases), Gemma Navarro (Unitat de VIH/SIDA, Parc Tauli Hospital Universitari-Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona), Vicenç Falcó Ferrer (Servei de Malalties Infeccioses, Hospital Universitari Vall d'Hebron, Vall d'Hebron Research Institute (VHIR)), Hernando Knobel (Servei de Malalties Infeccioses, Hospital del Mar).

Data sharing

The data collected for this study are available from the Centre for Epidemiological Studies of Sexually Transmitted Diseases and HIV/AIDS in Catalonia (CEEISCAT), the coordinating center of the PISCIS cohort study and from each of the collaborating hospitals upon request. Requests can be made via

https://pisciscohort.org/contacte/. The study protocol, the statistical codebook and codes for the analysis can be requested from RMI (raquel@bisaurin.org).

Conflicts of Interest

All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at

www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.JMM received a personal 80:20 research grant from Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, Spain, during 2017–23. The study was investigator-driven and thus independent of any pharmaceutical company. The funding sources were not involved in study design, data collection, analyses, report writing, or the decision to submit the paper.

References

- Vivancos, R.; Anderson, C.; Blomquist, P.; Balasegaram, S.; Bell, A.; Bishop, L.; Brown, C.S.; Chow, Y.; Edeghere, O.; Florence, I.; et al. Community Transmission of Monkeypox in the United Kingdom, April to May 2022. Eurosurveillance 2022, 27, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Duque, M.P.; Ribeiro, S.; Martins, J.V.; Casaca, P.; Leite, P.P.; Tavares, M.; Mansinho, K.; Duque, L.M.; Fernandes, C.; Cordeiro, R.; et al. Ongoing Monkeypox Virus Outbreak, Portugal, 29 April to 23 May 2022. Eurosurveillance 2022, 27, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J.I.; Montalbán, E.G.; Bueno, S.J.; Martínez, F.M.; Juliá, A.N.; Díaz, J.S.; Marín, N.G.; Deorador, E.C.; Forte, A.N.; García, M.A.; et al. Monkeypox Outbreak Predominantly Affecting Men Who Have Sex with Men, Madrid, Spain, 26 April to 16 June 2022. Eurosurveillance 2022, 27, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022 May 21. Multi-Country Monkeypox Outbreak in Non-Endemic Countries Available online: available: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON385. Accessed by August 31, 2023.

- Selb, R.; Werber, D.; Falkenhorst, G.; Steffen, G.; Lachmann, R.; Ruscher, C.; McFarland, S.; Bartel, A.; Hemmers, L.; Koppe, U.; et al. A Shift from Travel-Associated Cases to Autochthonous Transmission with Berlin as Epicentre of the Monkeypox Outbreak in Germany, May to June 2022. Eurosurveillance 2022, 27, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Antinori, A.; Mazzotta, V.; Vita, S.; Carletti, F.; Tacconi, D.; Lapini, L.E.; D’Abramo, A.; Cicalini, S.; Lapa, D.; Pittalis, S.; et al. Epidemiological, Clinical and Virological Characteristics of Four Cases of Monkeypox Support Transmission through Sexual Contact, Italy, May 2022. Eurosurveillance 2022, 27, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Nuzzo, J.B.; Borio, L.L.; Gostin, L.O. The WHO Declaration of Monkeypox as a Global Public Health Emergency. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association 2022, 328, 615–617. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization 2022-23 Mpox (Monkeypox Outbreak: Global Trends.

- Bunge, E.M.; Hoet, B.; Chen, L.; Lienert, F.; Weidenthaler, H.; Baer, L.R.; Steffen, R. The Changing Epidemiology of Human Monkeypox—A Potential Threat? A Systematic Review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2022, 16, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Thornhill, J.P.; Barkati, S.; Walmsley, S.; Rockstroh, J.; Antinori, A.; Harrison, L.B.; Palich, R.; Nori, A.; Reeves, I.; Habibi, M.S.; et al. Monkeypox Virus Infection in Humans across 16 Countries - April-June 2022. N Engl J Med 2022. [CrossRef]

- Thornhill, J.P.; Palich, R.; Ghosn, J.; Walmsley, S.; Moschese, D.; Cortes, C.P.; Galliez, R.M.; Garlin, A.B.; Nozza, S.; Mitja, O.; et al. Human Monkeypox Virus Infection in Women and Non-Binary Individuals during the 2022 Outbreaks: A Global Case Series. The Lancet 2022, 400, 1953–1965. [CrossRef]

- Mitjà, O.; Alemany, A.; Marks, M.; Lezama Mora, J.I.; Rodríguez-Aldama, J.C.; Torres Silva, M.S.; Corral Herrera, E.A.; Crabtree-Ramirez, B.; Blanco, J.L.; Girometti, N.; et al. Mpox in People with Advanced HIV Infection: A Global Case Series. The Lancet 2023, 401, 939–949. [CrossRef]

- Bruguera, A.; Nomah, D.; Moreno-Fornés, S.; Díaz, Y.; Aceitón, J.; Reyes-Urueña, J.; Ambrosioni, J.; Llibre, J.M.; Falcó, V.; Imaz, A.; et al. Cohort Profile: PISCIS, a Population-Based Cohort of People Living with HIV in Catalonia and Balearic Islands. Int J Epidemiol 2023, 52, e241–e252. [CrossRef]

- Government of Catalonia. Public Program of Data Analysis for Health Research and Innovation in Catalonia –PADRIS–. AQuAS. Barcelona. Available at: https://aquas.gencat.cat/ca/ambits/analitica-dades/padris/ [Accessed 20 Mar 2022].

- Quan, H.; Li, B.; Couris, C.M.; Fushimi, K.; Graham, P.; Hider, P.; Januel, J.M.; Sundararajan, V. Updating and Validating the Charlson Comorbidity Index and Score for Risk Adjustment in Hospital Discharge Abstracts Using Data from 6 Countries. Am J Epidemiol 2011, 173, 676–682. [CrossRef]

- States, U.; Riser, A.P.; Hanley, A.; Cima, M.; Lewis, L.; Saadeh, K.; Alarcón, J.; Smith, M.; Rehman, T.; Lubelchek, R.; et al. Epidemiologic and Clinical Features of Mpox-Associated Deaths —. 2023, 72, 404–410.

- Wolff Sagy, Y.; Zucker, R.; Hammerman, A.; Markovits, H.; Arieh, N.G.; Abu Ahmad, W.; Battat, E.; Ramot, N.; Carmeli, G.; Mark-Amir, A.; et al. Real-World Effectiveness of a Single Dose of Mpox Vaccine in Males. Nat Med 2023, 29. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Rates of Mpox Cases by Vaccination Status Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/cases-data/mpx-vaccine-effectiveness.html#print. Accessed by August 31, 2023.

- Dimitrov, D.; Adamson, B.; Matrajt, L. Evaluation of Mpox Vaccine Dose-Sparing Strategies. PNAS Nexus 2023, 2. [CrossRef]

- Kota, K.K.; Hong, J.; Zelaya, C.; Riser, A.P.; Rodriguez, A.; Daniel, L.; Spicknall, I.H.; Kriss, J.L.; Lee, F.; Boersma, P.; et al. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Mpox Cases and Vaccination Among Adult Males — United States , May – December 2022. 2023, 1–10.

- Birkett, M.; Neray, B.; Janulis, P.; Phillips, G.; Mustanski, B. Intersectional Identities and HIV: Race and Ethnicity Drive Patterns of Sexual Mixing. AIDS Behav 2019, 23, 1452–1459. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).