1. Introduction

A key issue in healthcare is patient safety. Several studies have shown that safety culture and the related concept of safety climate are related to clinical behaviors such as error reporting [

1], reduction of adverse events [

2,

3], and reduction of mortality [

4,

5,

6].

The development of a culture of safety is the focus of many efforts to improve patient safety and quality of care in acute care facilities [

6,

7]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), developing a culture of safety is the basis for improving the quality of health care [

8]. One of the essential steps to improve patient safety is the promotion of a culture of patient safety (PSC) [

6]. PSC is defined as “the product of individual and group values, attitudes, perceptions, competencies, and behavior patterns that determine an organization's health and safety management commitment, style, and competence”. In fact, it is able to influence the behaviors, attitudes, and cognitions of physicians and staff at work, providing guidance on the relative priority of patient safety over other goals (e.g., performance or efficiency) [

9].

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), in describing the culture of safety, points out that the dimensions to be considered should include teamwork, staffing, adherence to procedures, training and skills, non-punitive response to errors, transfers, feedback and incident reporting, open communication, supervisor expectations and actions, overall perception of safety, management support, and "organizational learning [

10]. One approach to optimizing safety outcomes in health care is often referred to as Safety I. This system, through retrospective investigation, assesses the causes of individual errors or failures to redesign the system and eliminate similar future occurrences [

11]. However, these measures may be better identified in Safety II, which is an approach to safety that recognizes complex systems and unpredictable circumstances, imposing flexibility and resilience within systems and among individuals to avoid errors [

11].

The concept of “safety culture” was introduced in 1991 by the International Atomic Energy Authority (IAEA) in the wake of the 1986 Chernobyl disaster [

12] and has since been emphasized globally, defining it as, “Safety culture is the enduring value and priority placed on the safety of workers and all the public, in all groups and at all levels of an organization” [

13]. In 2022, to further urge all countries to sustain attention and information on the topic of safety culture especially in the context of care and the assisted person, the World Health Organization (WHO) has promoted "World Patient Safety Day" [

14].

The culture of safety needs to be increasingly widespread because problems can arise from the adverse events and unintentional harm that can occur as a result of health care provided by any member of the health care institution [

15]. When care is directed toward patients in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, safety must be even more careful. In agreement with the fact that research on critically ill patients is difficult; and research on critically ill children who are in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) becomes crucial, as many errors threaten patient safety because of the complex situations that occur [

16].

Challenges can arise from the heterogeneity of patients in terms of age and comorbidities, often with ill-defined clinical syndromes and rapidly changing physiology. Other challenges arise from the personality of pediatric intensivists. In agreement with Nicholson [

17] who wrote that “pediatric intensivists are not strong advocates of the scientific method” and in agreement with Zimmerman [

18] who states that pediatric intensivists are “prone to action rather than deliberate inquiry”. Moreover, children's health problems, disease processes, and outcomes may be very different in countries with different epidemiology and with different wealth and resources.

In order to increase the literature in terms of nursing safety culture, this study aimed to bring out the dimensions of PSC from the perspective of nurses, who play an important role in health care delivery6 and are in contact with patients in PICUs [

19]. The role of nurses offers several opportunities to reduce adverse events and catch errors before they occur. A positive work environment, management commitment, nurses' level of education, and error reporting have a positive impact on patient safety outcomes [

20]. In the PICU environment, where children have a higher severity of illness, a qualitative research approach helps to identify failure factors [

11]. In accordance with an analysis conducted by Salem et al. [

19], patient safety was a primary goal of nursing before 1900, and reflection on this analysis can inspire nurses to take actions that improve patient safety today.

Given this background, the objectives of the study were: (I) to describe the clinical risk perceptions of nurses working in PICUs; (II) to identify nurses' perceived adverse events and risk factors; and (III) to describe their perceptions of the nurse's role in patient safety.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

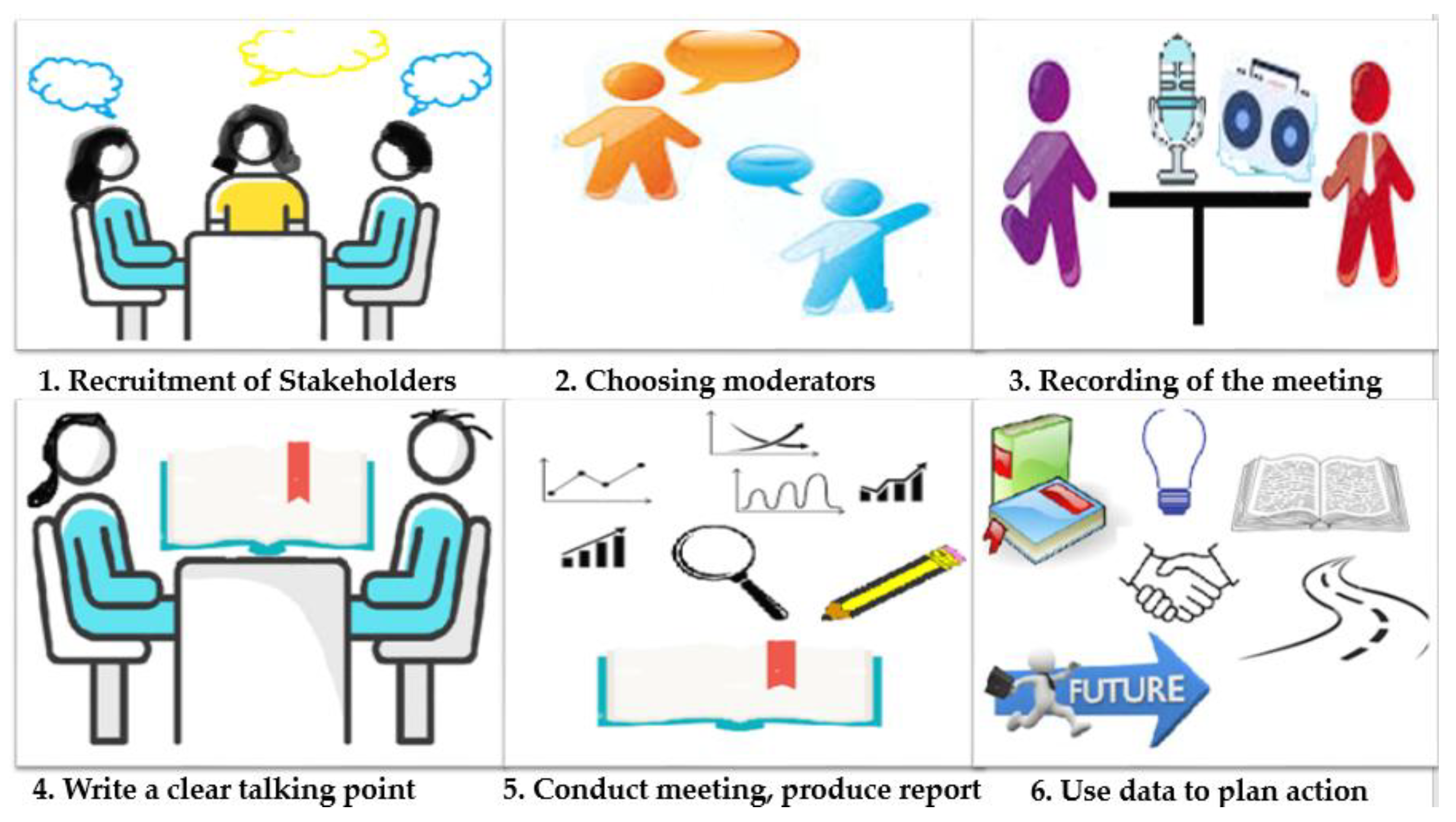

The study is a focus group research conducted between May and December 2022 with a panel of PICU nurses from the University Hospital of Padua in order to collect respondents' attitudes, feelings, beliefs, experiences, and reactions with respect to clinical risk, adverse events, and patient safety. As defined by Powell et al. [

21] a focus group is a group of people selected and brought together by researchers to discuss and comment, from personal experience on the topic being researched. Based on the parameters established by Merton and Kendal [

22], the participants selected for our study were stakeholders with a specific experience or opinion on the topic under study, and the subjective experiences of the participants were explored using an explicit interview guide (

Figure 1).

2.2. Partecipants in the study and Procedures

A qualitative method was used to analyze stakeholders' experiences and understanding of the events. A 2-hour focus group session was conducted with 9 nurses with different work experiences in PICUs, 2 facilitators, and 1 observer.

Participants were informed about the objectives and methods of the study. They were also informed that they would be recorded and implied consent was obtained. Participation in the study was voluntary and participants could withdraw at any time.

Eight open-ended questions were used (

Figure 2). The session was divided into three parts: the first part (questions numbers 1, 2, 3, 4) focused on the critical issues and adverse events in PICUs and the factors that could solve these critical issues; the second part (questions numbers 5, 8) focused on the measures already implemented in PICUs and those that could be improved; finally, a third part (questions numbers 6, 7) focused on the role of the nurse.

Participants were asked what nurses do for clinical risk management, what their role should be, what they already do, and what they would like to develop in the future. No training was provided prior to the focus group, and all responses were based solely on the participants' experience.

2.3. Data Anaysis Procedures

The text generated by a transcriber from the session audio was analyzed and coded by an independent author with extensive experience in qualitative research. Conventional content analysis with a comparative approach was used, and general principles for ensuring the quality of qualitative research were followed [

23,

24,

25]. The transcriber identified and collected words and short phrases to assign a summative, salient, essence-capturing, and/or evocative attribute or summary. A summary report was prepared that outlined the domains, codes, and quotations. Finally, the work was evaluated by the facilitators and the outside observer.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of Study Partecipants

Nine nurses from the University Hospital of Padua agreed to participate in the study, including 7 females and 2 males, aged 30±10 years, with varying levels of experience working in PICUs and length of service (

Table 1).

3.2. Identified themes that describe perceived clinical risk in the PICU

From the focus group discussion, 9 themes were identified that describe the perception of clinical risk in the PICU (

Table 2). The themes identified are mainly related to the characteristics of the workplace or work management. Only two themes relate to the specific characteristics of the professionals or patients.

3.1.1. Teamwork

Participants identified a critical issue in the poor organization of work among staff: first, there is incomplete communication between physicians and nurses (quote 1), which occurs not only at the patient's bedside, but also during briefing and debriefing between physicians and nurses or between nurses.

Another critical issue identified in terms of teamwork is the lack of control in the administration of therapy by at least two nurses or a nurse and a physician, which can be seen in a broader sense, again reported by focus group participants, as a lack of discussion among colleagues (quote 2) and collaboration among different health professionals. Dual review also affects shared medical records and metabolic screening (citation 3).

3.1.2. Specific training

Participants in the focus group reveal a perceived training gap for residents in the topic of clinical risk, and for nurses hospitals did not provide continuing education on this topic arises from the lack of organizational knowledge of the entire team (quote 4), from the inadequate support of the new employee (from both the medical and nursing point of view, e.g. lack of knowledge of the correct compilation of the therapy sheet or inability to read the prescription correctly by nurses), the absence of specific and mandatory courses on this topic. The factors that have increased the clinical risk are due to the lack of specific training, but also to the lack of awareness, which results in the failure of the nurse coordinator to request specific training (quote 5) from the central hospital management or the hospital training service. Solutions to this gap may be to increase the use of incident reporting after specific training, and training sessions with high fidelity drills (quote 6).

3.1.3. Time management

Another criticality that emerged is related to time management, both in the preparation of therapy, which is often interrupted by questions from colleagues or the patient's family, and for more complex procedures that are not adequately managed in terms of time (time of day to perform them).

What the participants report to the medical management is also a lack of care priorities (quote 7), which correlates with poor time management, both from the organizational point of view of invasive procedures, as well as handover, prescriptions, etc. (quote 8).

3.1.4. Team comunication

Participants identify another issue as risky due to the possibility of making mistakes, which is more related to communication within the team, an aspect that can be transversal and touches on time management and teamwork, but which is characterized in its own way by reported episodes of inadequate or incomplete information (quote 9), incomplete communication between doctors and nurses during briefings, deliveries that focus on certain problems without emphasizing others, and also the lack of a common procedure for handover, as well as the absence of a multidisciplinary meeting with doctors and nurses.

3.1.5. Management

An aspect criticized by the participants in relation to the care coordinator is the inadequate management of shifts, which can lead to many hours of overtime for some nurses, irregular shifts with a consequent increase in fatigue and the risk of errors. In addition, an inadequate distribution of activities among the different health professionals is reported: this is mainly linked to the expertise of the individual, so that those with more seniority tend to intervene several times in more complex procedures and "leave" the care of their patients to a colleague, with a significant increase in the risk of error (citation 10).

Finally, with regard to the care coordinator, a poor organization of dangerous drugs is reported, for which it would be necessary to find common solutions for their management and storage.

3.1.6. Individual errors

The increase in clinical risk is certainly related to the individual: in particular, there are "errors" that require careful study and observation to identify and overcome. First of all, the participants reported illegible prescriptions by doctors (quote 11) and, in the worst case, an incorrect prescription, for example in dosage, posology or administration times. Another point concerns the poor management of patient files, the disorganization that can lead to delays (n°12), the solution to which is necessarily linked to a better awareness and training of the team regarding clinical risks.

3.1.7. Facility criticity

In addition to the risk related to the human factor seen in the previous paragraph, the nurses in the focus group also reported on the shortcomings of the facilities in the hospital, such as a PICU linked to old models of care, therefore dispersed and with inadequate spaces (quote 13), problems related to the packaging of drugs (similar packaging), which can lead to confusion and errors in an emergency situation.

Participants suggested as a first solution to have a complete therapy cart with a room dedicated to the preparation of drugs and infusions (quote 14).

3.1.8. Patient Factors/Characteristics

One of the main criticalities in care management is related to the patient's situation, who may face accidental falls, accidental device removal (CVC, PICC), accidental extubation (rate 15). These variables are also difficult for nurses to identify and resolve. A solution could be linked to the ability to keep nurses in the room and educate them adequately about these possible events.

3.1.9. Standardization

A final element emphasized by the participants in the focus group is the need to standardize the different activities as much as possible: the need to use labels to distinguish the different infusions (perhaps with different colors), the need to standardize recipes and to use IT tools as much as possible (quote 16). Finally, also related to the need for better communication and training, there is also the possible solution of reducing the risk of errors by introducing checklists (quote 17).

4. Discussion

The assessment of the results of the focus group highlighted critical points in the different phases of the processes and procedures within the system. The main difficulty identified by nurses during the focus group is the relationship between working in a high quality PICU and ensuring optimal patient safety with scarce resources. Teamwork, communication, and a culture of safety are essential factors in providing effective and safe care [

20] especially in the PICU due to the criticality of the patient. Among the various articles in the literature [

20,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34] that have studied practices and systems focused on improving these aspects to enhance the culture of patient safety, Merandi et al. [

11], outline that the main approach used to optimize patient safety in health care, defined Safety I. However, this system involves a retrospective investigation after a failure to determine individual failures to preserve from eliminating future events. Therefore, the behaviors of Safety [

35] are those that prevent people from repeating the same mistakes; in fact, people focused on the event and not enough on prevention and improvement. in the evolution towards Safety II, which focuses on what is already positive in the system, recognizing that systems are complex and seeing human behavior as a source of creativity versus a dangerous threat, people can be better engaged[

11]. Promotion of patient safety culture can best be synthesized as a series of interventions of leadership, behavior change and above all teamwork [

6].

Multiprofessional care is defined as the provision of collaborative and integrated health care by professionals from a variety of disciplines and professions, with different levels of training and experience, in response to the needs of the patient [

36]. Reeves et al. [

37], in collaboration with the UK Centre for Advancement of Interprofessional Education (CAIPE), have published the CAIPE framework, which identifies three key areas, each contributing to multiprofessional teamwork: relational factors; processual factors; and organizational and contextual factors. Taken together, these findings suggest that there is evidence to support the effectiveness of such interventions in improving clinicians' and staff's perceptions of elements of safety culture.

The themes that emerged from the focus group analysis are part of these factors:

- Themes "1. Teamwork" and "4. Team communication" reflect the relational factors. These factors describe the mentality and influence the relationship between professionals. There are two aspects that need to be taken into consideration that can hinder the proper management of the multiprofessional team: the power, hierarchy, composition together with the roles of the team, and the tension between senior and junior health professionals, doctors and nurses, and between the parents of a child and the hospital staff in the PICU [

36]. To have a united and cohesive team, regardless of hierarchy, responsibility should be shared among a network of equal partners [

36].

Teamwork is crucial in causing and preventing adverse events [

20]. Effective communication is important for maintaining patient safety, and it exists when there is a culture of respect, fostered by shared mental models and efficient communication among team members, including the patient's parents and relatives, which form the basis for effective team management in a PICU [

36]. In addition, encouraging nurses to report events is very important for improving patient safety; however, this requires a non-punitive environment where people are not blamed [

20].

- Themes "3. Team management," "6. Individual errors," "8. Patient factors/characteristics," and "9. Standardization" can be included in the process factors. Process factors describe the processes involved in teamwork. To work competently in a team is a learning process, it means to be part of a very complex system of activities (routines and rituals, roles and rules with a high load of unpredictability and urgency). The challenge is to learn by structuring clinical work as a learning process to improve patient safety; in health care organizations, formal and team-based learning is possible in simulation [

36,

38]. Creating effective teamwork and enabling learning on the job requires leadership and cultural change that favors the management of the multiprofessional team [

36]. It is essential to view errors as important learning opportunities to improve the culture of patient safety rather than as personal failures. This type of vision creates a guilt-free environment in which nurses are able to identify and promptly report errors, thereby improving patient safety. Developing a culture of safety requires a zero-fault and error-reporting environment [

20].

- Themes "2. Specific training", "5. Management" and "7. Structural criticalities" can be included in organizational and contextual factors. Organizational, leadership and contextual culture are responsible for the organizational environment and are considered important factors in the management of the multiprofessional team [

39]. The literature shows that managers' expectations and actions, feedback and communication about errors, teamwork between hospital units [

40,

41] and hospital handoffs and transitions [

41] predict the overall perception of patient safety culture [

20,

39,

40]. This demonstrates the importance of managers encouraging a commitment to patient safety by providing feedback and communication about unit errors and proactively responding to staff recommendations to improve patient safety and prevent errors from occurring [

20]. It is important to note that nurses' perceptions and recognition of patient safety culture increase with professional experience if they work in teaching hospitals [

20].

The results of the current study are consistent with other studies [

6,

13,

20,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41] showing that communication about errors, teamwork across hospital units, and specific training are predictors of overall perceptions of patient safety culture.

The limitations of this study are that the focus group questions were created specifically for this study; and the data were obtained from a small sample and a single center.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the importance of promoting a culture of safety in a sensitive and critical context such as the PICU and identifies 9 themes that describe nurses' perceptions of clinical risk in the PICU.

Promoting a culture of safety requires replacing the traditional culture of shame/blame with a non-punitive culture, sharing information, and learning from events. In fact, the culture of safety can only take place through the implementation of: multi-professional meetings, workshops and educational activities that promote a culture of respect and shared mental models; individual and team briefings-debriefings, feedback, focus groups, coaching and mentoring; communication training; simulation training; mortality and morbidity conference; critical incident reporting system; dissemination of reported errors and solutions; recognition and support of bottom-up initiatives and projects.

Nurses in PICUs need to be committed to promoting patient safety, knowing that by doing so, the organization will optimize its processes, staff well-being will increase, nurses can improve their care and outcomes, and fulfill their mission.

Implications.

- Promoting a culture of safety could improve the quality-of-care delivery processes in a PICU setting.

- The implementation of multi-professional meetings, workshops and educational activities that promote a culture of respect could be used to develop policies that will improve the quality-of-care delivery.

- The involvement of PICU nurses in promoting patient safety could improve break down the barriers that keep nurses from fulfilling their role.

- Explore future research on the problem of the study to further develop our understanding of the topic and find new strategies for nurturing patient safety culture in PICU.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P., P.C.F., and V.A.; methodology, P.C.F., B.T., V.S., and V.C.; software, S.M.A.; validation, A.P., P.C.F., V.A. and S.M.A.; resources, A.P., P.C.F, V.S. ; data curation, A.P.,B.T. and V.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P and P.C.F.; writing—review and editing, S.M.A..; visualization, P.C.F., B.T., V.S., V.C.; supervision, S.M.A, V.A. and M.C.; project administration A.P., P.C.F., V.A., M.C and S.M.A.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol included full assurance of anonymity, discretion of participation, and absence of risk, conflict of interest, and incentives for participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We express special thanks to the study participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Braithwaite, J.; Westbrook, M.T.; Travaglia, J.F.; Hughes, C. Cultural and associated enablers of, and barriers to, adverse incident reporting. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010, 19, 229–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, S.; Lin, S.; Falwell, A.; Gaba, D.; Baker, L. Relationship of safety climate and safety performance in hospitals. Health Serv Res. 2009, 44, 399–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardon, R.E.; Khanna, K.; Sorra, J.; Dyer, N.; Famolaro, T. Exploring relationships between hospital patient safety culture and adverse events. J Patient Saf. 2010, 6, 226–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estabrooks, C.A.; Tourangeau, A.E.; Humphrey, C.K.; Hesketh, K.L.; Giovannetti, P.; Thomson, D.; et al. Measuring the hospital practice environment: a Canadian context. Res Nurs Health. 2002, 25, 256–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sexton, J.B. A Matter of Life or Death: Social, Psychological, and Organizational Factors Related to Patient Outcomes in the Intensive Care Unit. Austin: Univ of Texas, 2002.

- Weaver, S.J.; Lubomksi, L.H.; Wilson, R.F.; et al. Promoting a Culture of Safety as a Patient Safety Strategy: A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med. 2013, 158, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, L.T.; Corrigan, J.M.; Donaldson, M.S. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Pr; 2000.

- WHO. Patient safety in developing and transitional countries: new insights from Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2011.

- Zohar, D.; Livne, Y.; Tenne-Gazit, O.; Admi, H.; Donchin, Y. Healthcare climate: a framework for measuring and improving patient safety. Crit Care Med. 2007, 35, 1312–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessels, A.J.; Murray, M.T.; Cohen, B.; Larson, E.L. Perception of Patient Safety Culture in Pediatric Long-Term Care Settings. J Healthc Qual. 2018, 40(6), 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merandi, J.; Vannatta, K.; Davis, J.T.; et al. Safety II Behavior in a Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. Pediatric. 2018, 141(6), e20180018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.D. Towards a model of safety culture. Safety Science 2000, 36, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomides, M.D.A.; Fontes, A.M.S.; Silveira, A.O.S.M.; Sadoyama, G. Patient safety culture in the intensive care unit: cross-study. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2019, 13(6), 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). World Patient Safety Day. Available from https://www.who.int/campaigns/world-patient-safety-day/2022 (Accessed on July 23, 2023).

- Mira, J.J.; Cho, M.; Montserrat, D.; Rodríguez, J.; Santacruz, J. Elementos clave en la implantación de siste- mas de notificación de eventos adversos hospitalarios en América Latina. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2013, 33(1), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.J.; Argent, A.; Festa, M.; et al. The intensive care medicine clinical research agenda in paediatrics. Intensive Care Med 2017, 43, 1210–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, C.E.; Gans, B.M.; Chang, A.C.; Pollack, M.M.; Blackman, J.; Giroir, B.P.; Wilson, D.; Zimmerman, J.J.; Whyte, J.; Dalton, H.J.; Carcillo, J.A.; Randolph, A.G.; Kochanek, P.M. Pediatric critical care medicine: planning for our research future. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2003, 4, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, J.J.; Anand, K.J.; Meert, K.L.; Willson, D.F.; Newth, C.J.; Harrison, R.; Carcillo, J.A.; Berger, J.; Jenkins, T.L.; Nicholson, C.; Dean, J.M.; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network Research as a standard of care in the PICU. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2016, 17, e13–e21.

- Salem, M.; Labib, J.; Mahmoud, A.; Shalaby, S. Nurses' Perceptions of Patient Safety Culture in Intensive Care Units: A Cross-Sectional Study. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019, 7(21), 3667–3672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammouri, A.A.; Tailakh, A.K.; Muliira, J.K.; Geethakrishnan, R.; Al Kindi, S.N. Patient safety culture among nurses. Int Nurs Rev. 2015, 62(1), 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, R.A.; Single, H.M. Focus groups. International Journal of Quality in Health Care 1996, 8(5), 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton ,R.K.; Kendall ,P.L. The Focused Interview. American Journal of Sociology 1946, 51, 541-557.

- Hickey, G.; Kipping, C. A multi-stage approach to the coding of data from open-ended questions. Nurse Res. 1996, 4(1), 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005, 15(9), 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R.A.; Casey, M.A. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. Fourth Edition. Thousand Oaks, CA Sage Publications, 2009.

- Smith, F.; Plunkett, E. People, systems and safety: resilience and excellence in healthcare practice. Anaesthesia. 2019, 74(4), 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, P.W.; Muething, S.; Kotagal, U. et al. Improving situation awareness to reduce unrecognized clinical deterioration and serious safety events. Pediatrics. 2013, 131(1), e298-e308. 1.

- Brilli, R.J.; McClead, R.E. Jr; Crandall, W.V. et al. A comprehensive patient safety program can significantly reduce preventable harm, associated costs, and hospital mortality. J Pediatr. 2013, 163(6), 1638-1645.

- Hilliard, M.A.; Sczudlo, R.; Scafidi, L.; Cady, R.; Villard, A.; Shah, R. Our journey to zero: reducing serious safety events by over 70% through high-reliability techniques and workforce engagement. J Healthc Risk Manag. 2012, 32(2), 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyren, A.; Brilli, R.; Bird, M.; Lashutka, N.; Muething, S. Ohio Children's Hospitals' Solutions for Patient Safety: A Framework for Pediatric Patient Safety Improvement. J Healthc Qual. 2016, 38(4), 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McClead, R.E. Jr; Catt, C.; Davis, J.T. et al. An internal quality improvement collaborative significantly reduces hospital-wide medication error related adverse drug events. J Pediatr. 2014, 165(6), 1222-1229.e1.

- Muething, S.E.; Goudie, A.; Schoettker, P.J.; et al. Quality improvement initiative to reduce serious safety events and improve patient safety culture. Pediatrics 2012, 130(2), e423–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, T.H.; Teman, S.F.; Connors, R.H. A safety culture transformation: its effects at a children's hospital. J Patient Saf. 2012, 8(3), 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaffzin, J.K.; Harte, L.; Marquette, S.; et al. Surgical Site Infection Reduction by the Solutions for Patient Safety Hospital Engagement Network. Pediatrics. 2015, 136(5), e1353–e1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollnagel. E. Safety-I and Safety-II: The Past and Future of Safety Management. First Edition. Farnham, Surrey, Ashgate Publishing, 2014.

- Stocker, M.; Pilgrim, S.B.; Burmester, M.; Allen, M.L.; Gijselaers, W.H. Interprofessional team management in pediatric critical care: some challenges and possible solutions. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016, 9, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, S.; Lewin, S.; Espin, S.; Zwarenstein, M. Interprofessional Team work for Health and Social Care. In: A Conceptual Framework for Interprofessional Teamwork. Chichester, West Sussex, Ames, IA, John Wiley and Sons, 2010.

- Jacqueline, E.; Lauren, S. Nurse-Driven Care in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit: a Review of Recent Strategies to Improve Quality and Patient Safety. Curr Treat Options Peds 2017, 3, 236–245. [Google Scholar]

- El-Jardali, F.; Dimassi, H.; Jamal, D.; Jaafar, M.; Hemadeh, N. Predictors and outcomes of patient safety culture in hospitals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmadi, H.A. Assessment of patient safety culture in Saudi Arabian hospitals. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010, 19(5), e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballangrud, R.; Hedelin, B.; Hall-Lord, M.L. Nurses’ perceptions of patient safety climate in intensive care units: a cross-sectional study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2012, 28(6), 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).