1. Introduction

With the COVID - 19 pandemic, attitudes toward obtaining and sharing medical data have changed significantly in Europe and around the world. The pandemic demonstrated the importance of coordination among European countries to protect people’s health, both in times of crisis and in normal times, when we can address underlying health problems, invest in robust health systems and train medical personnel. November 30, 2022. The European Union adopted the EU Global Health Strategy, a document outlining three main goals for health system development such as deliver better health and well-being of people across the life course, strengthen health systems and advance universal health coverage; and a prevent and combat health threats, including pandemics [

1]. As part of its activities, the European Union is also developing the European Health Data Space, which aims to support individuals to take control of their own health data, supports the use of health data for better healthcare delivery, better research, innovation and policy making and enables the EU to make full use of the potential offered by a safe and secure exchange, use and reuse of health data [

2]. Biobanking is a key process related to the development of the health care system. Collecting and storing biological samples allows building collections that can be used to search for new diagnostic and therapeutic methods thus contributing to the development of health care systems both in Poland, Europe and the world. The Polish Network of Biobanks, established thanks to the efforts of the BBMRI.pl consortium, has been operating in Poland since 2017. It currently includes more than 50 units spread across the country. The development of biotechnology stimulates the use and creation of new biobanks. These units enable the identification of genes, support the development of personalized diagnostic, preventive and therapeutic programs. Combining health and genetic data from large populations also means that complex relationships between genes, environment and disease can be studied [

3]. While biobanks are an important resource for biomedical research and ultimately the health care system, there are also ethical, legal and social concerns about their use, such as donor privacy and confidentiality, data protection, the use of genetic technologies and the commercialization of genetics and genetic technologies or the commercialization of genetic products. However, in order for these repositories of data and samples to be useful, they must be fed with information from donors who are willing to participate in scientific research and donate their biological material. Therefore, it was decided to conduct a survey on a representative group of adult Poles to determine their awareness, attitudes and willingness to donate their biological material and medical data to a biobank. The information obtained will allow a better understanding of the needs, expectations and concerns of potential donors and will help build conditions for effective communication between biobank staff and potential donors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey

The survey was conducted among a nationwide group of 1,052 Poles aged 18 and over where the totals for gender, age and place of residence were selected according to representation in the population of adult Poles. The survey was conducted using the Computer Assisted Web Interview (CAWI) method with the help of Ariadna, a nationwide survey panel company. The survey was conducted between January and February 2023.

The survey questionnaire was distributed with the help of the Ariadna company. Upon completion of the survey, Ariadna provided a cleaned and anonymized dataset. Each panelist is subject to verification upon registration and is guaranteed full anonymity and confidentiality of their personal information. They then receive an invitation to complete the survey sent via email, to the email address they provided when registering with the panel. Respondents receive a message with a coded and personalized link to the survey. Real people with established identities took part in the survey. The survey was not conducted using random selection methods, where respondents are collected from ad hoc roundups via pop-ups displayed on the Internet to random people, or via mass mailings or online surveys.

2.2. Questionnaire development

The questionnaire contained 23 questions about Poles’ knowledge, opinions, beliefs and attitudes toward biobanking and scientific research in which biological material is collected. The questionnaire for the survey was based on open-access questions used in the 2010 Eurobarometer survey [

4] and questions used in the survey on public willingness to participate in biobanking in Switzerland published in 2021 by C. Brall et.al.[

5]. The questions were translated into Polish, consulted with experts and adapted to the specifics of Polish society. The questionnaire examined the level of awareness of biobanking, factors influencing the decision to donate biological material to a biobank, determined what the public’s expectations are regarding the supervision of biological material and data in biobanks, and examined attitudes and determined what factors influence parents’ decisions to donate their children’s biological material to a biobank. This publication only describes the areas of the level of awareness, the factors affecting the decision to donate material, and identifies public expectations.

2.3. Ethics Committee opinion

On 16/01/2023, by decision No. AKBE/3/2023, the study and the questionnaire received a positive opinion from the Ethics Committee at the Medical University of Warsaw.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were summarized using mean and standard deviation. In addition, median, interquartile range, range and kurtosis were presented. For nominal variables, counts and percentages were used to summarize. Sprearman’s Q was used for correlation analysis. A p-value (Hollander and Wolfe) was used to assess the significance of correlations. Due to multiple comparisons, a Benjamini-Hochberg correction was applied to the p-value. The relationship was considered significant at p<0.05. The analysis was conducted in the R language environment.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic characteristics of respondents

One thousand and fifty-two respondents (N = 1052) took part in the survey. The average age of respondents was 46.37 years (SD = 15.92). Slightly more women (N=567, 53.9%) participated in the survey than men (N=485, 46.1%). More than half of the respondents are in a relationship (N=573, 54.5%), and about a third of the participants said they were single (N=310, 29.5%). The remaining respondents are divorced (N=108, 10.3%) or widowed (N=61, 5.8%). Most respondents have a university degree (completed college degree N=357, 33.9% or bachelor’s degree N=87, 8.3%). Most respondents live in rural areas (N=390, 37.1%). Detailed demographic characteristics of the respondents are shown in

Table 1.

3.2. Awareness of research using biological material and biobanking

In 2023, N=701 (66.6%) respondents indicated that they had heard of scientific studies in which samples of biological material such as blood, saliva or urine are collected. N=146 (13.9%) of respondents were unsure or could not remember if they had ever heard of such research. More than half of respondents (N=613, 58.3%) have a positive opinion regarding scientific research in which samples of biological material are taken (N=441, 41.9% - rather positive, N=172 16.4% - positive), N=371 (35.3%) respondents have no opinion on the subject and only N=68 (6.5%) have a negative opinion (N=50, 4.8% - rather negative, N=18, 1.7% - negative). Only N=220 (20.9%) of respondents had previously encountered the term biobanking, and as many as N=674 (64.1%) had never heard of it before. The correlation analysis showed no relationship between education, place of residence, marital status or age and awareness of biobanking and related to scientific research in which biological material samples are supported. Detailed responses are shown in

Table 2.

N=619 (58.8%) respondents believe that they have to give consent for biobanking their biological samples, but only N=566 (53.8%) believe that they can withdraw such consent. It is noteworthy that as many as N=360 (34.2%) respondents do not know whether they have to give consent for biobanking and N=443 (42.1%) do not know whether they can withdraw the consent already given.

Respondents believe that a biobank should ask for consent every time samples are to be used for a new project - narrow consent (N=505, 48.0%). According to N=149 (14.2%) respondents, it is sufficient for them to give their consent once for the use of their samples in research projects - broad consent. Similarly, the correlation analysis showed no relationship between education, place of residence, marital status or age and knowledge of the rights that potential research participants have. It indicates a significant need to educate potential research participants about their rights and responsibilities, regardless of previously received education or place of residence. Detailed responses are presented in

Table 3.

The survey asked respondents to indicate which of the proposed definitions they thought best described the biobanking process. N=441 (41.9%) respondents indicated that in their opinion, biobanking is a process in which body fluid or tissue samples, genetic data and medical data (medical history, laboratory results, etc.) are collected and stored in order to better understand health and disease progression. As many as N=390 (37.1%) respondents did not know which of the proposed definitions best described the biobanking process. Detailed responses are shown in

Table 4.

3.3. Willingness to participate in the study and factors influencing the decision to donate biological material

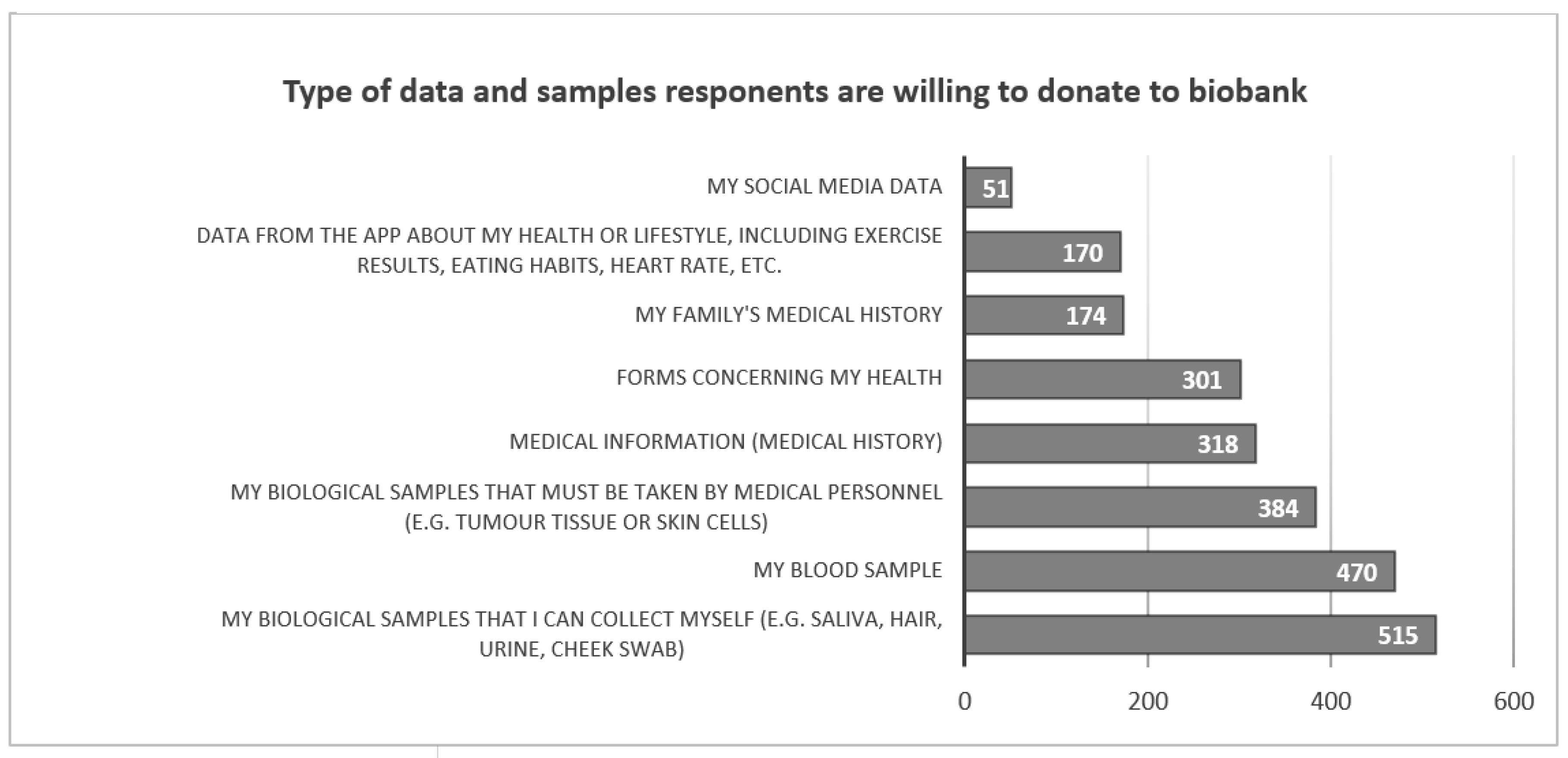

N=687 (65.3%) respondents would participate in a scientific study that biobanked biological material and health information. Those who agreed to participate in the study would be most willing to share samples that they can collect themselves (saliva, hair, urine, cheek swab) (N=515, 75.0%), a blood sample (N=470, 68.4%) or samples of biological material that must be collected by medical personnel (N=384, 55.9%). Respondents are less willing to provide medical history (N=318 46.3%), complete health forms (N=301, 43.8%), family medical history (N=174, 25.3%) or health data from sports apps (N=170, 24.7%). Only N=51 (7.4%) respondents consider sharing the information they post on their social media (

Figure 1).

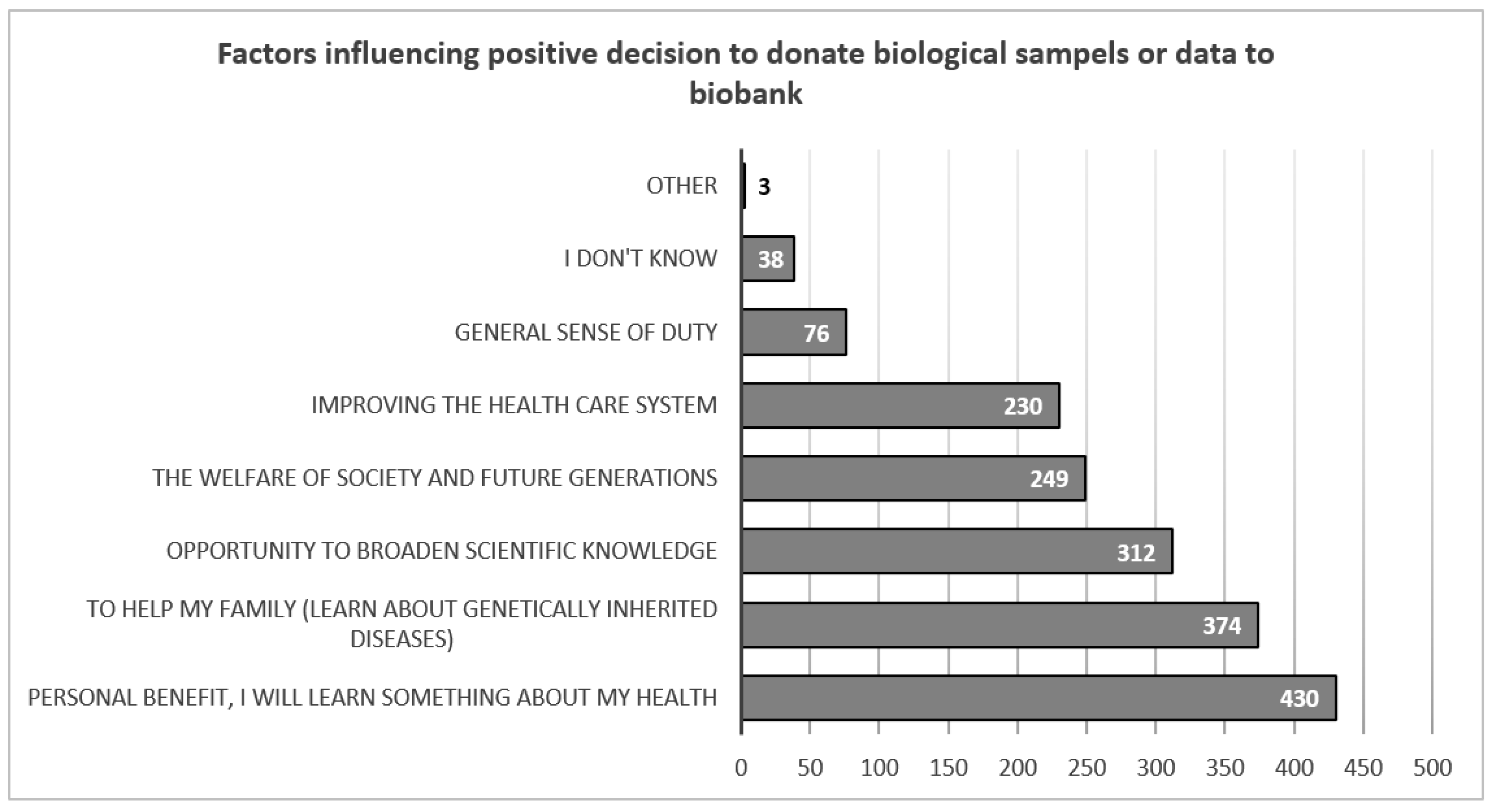

The greatest motivation for respondents to take part in a research study in which information about their health would be biobanked is the personal benefits they could gain from such a study (N=430, 62.6%) or the benefits their family could gain (N=374. 54.8%). The least motivating factor is a general sense of duty, with only N=76 (11.1%) respondents taking this into account when making their decision (

Figure 2).

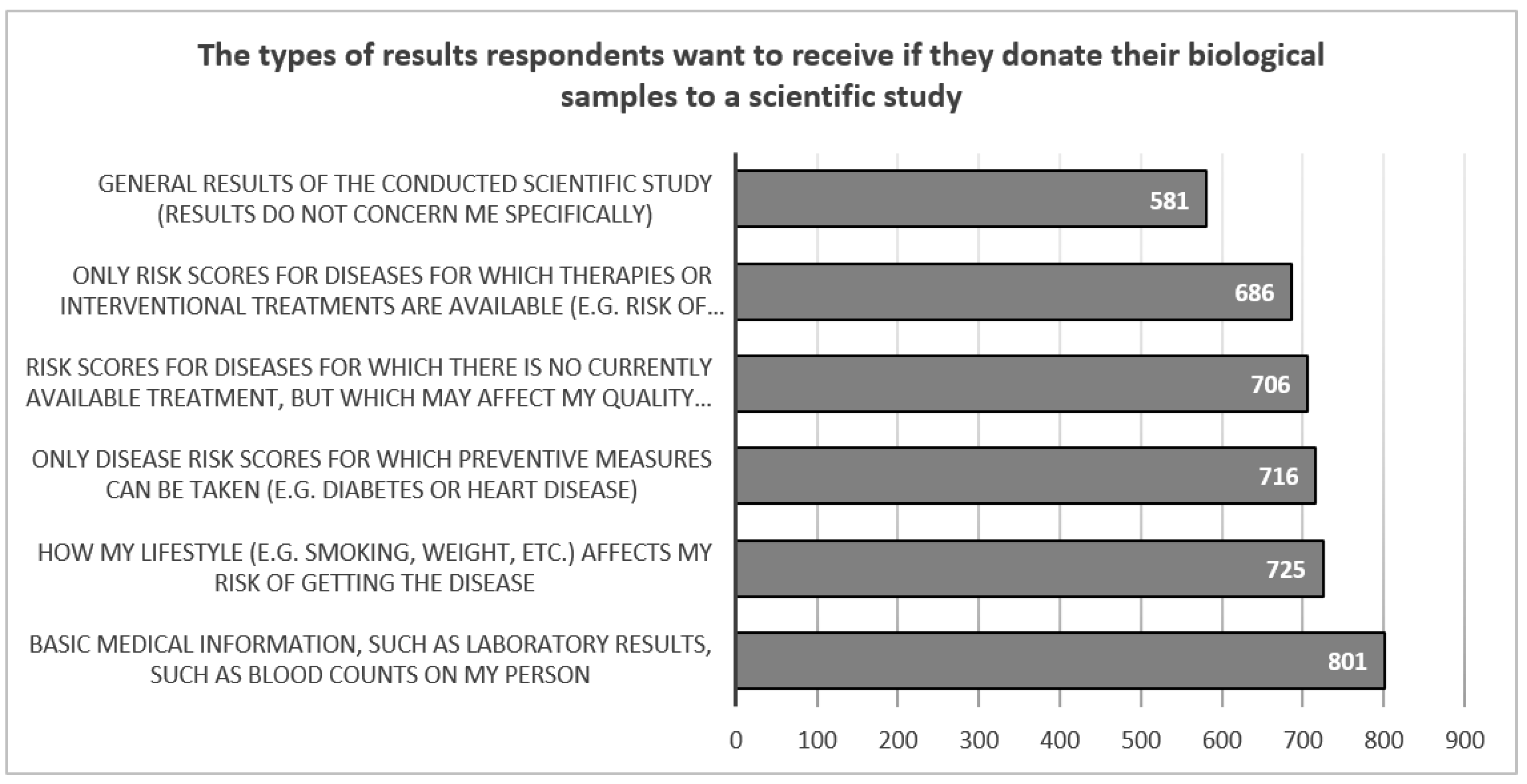

Respondents who would participate in a scientific study conducted in a biobank would be most interested in receiving basic laboratory results such as blood counts (N=801, 76.1%) and information on how their lifestyle affects their risk of contracting a disease (N=725, 68.9%). They are least interested in general study results, with only slightly half (N=581, 55.2%) wanting such information (

Figure 3).

3.4. Concerns

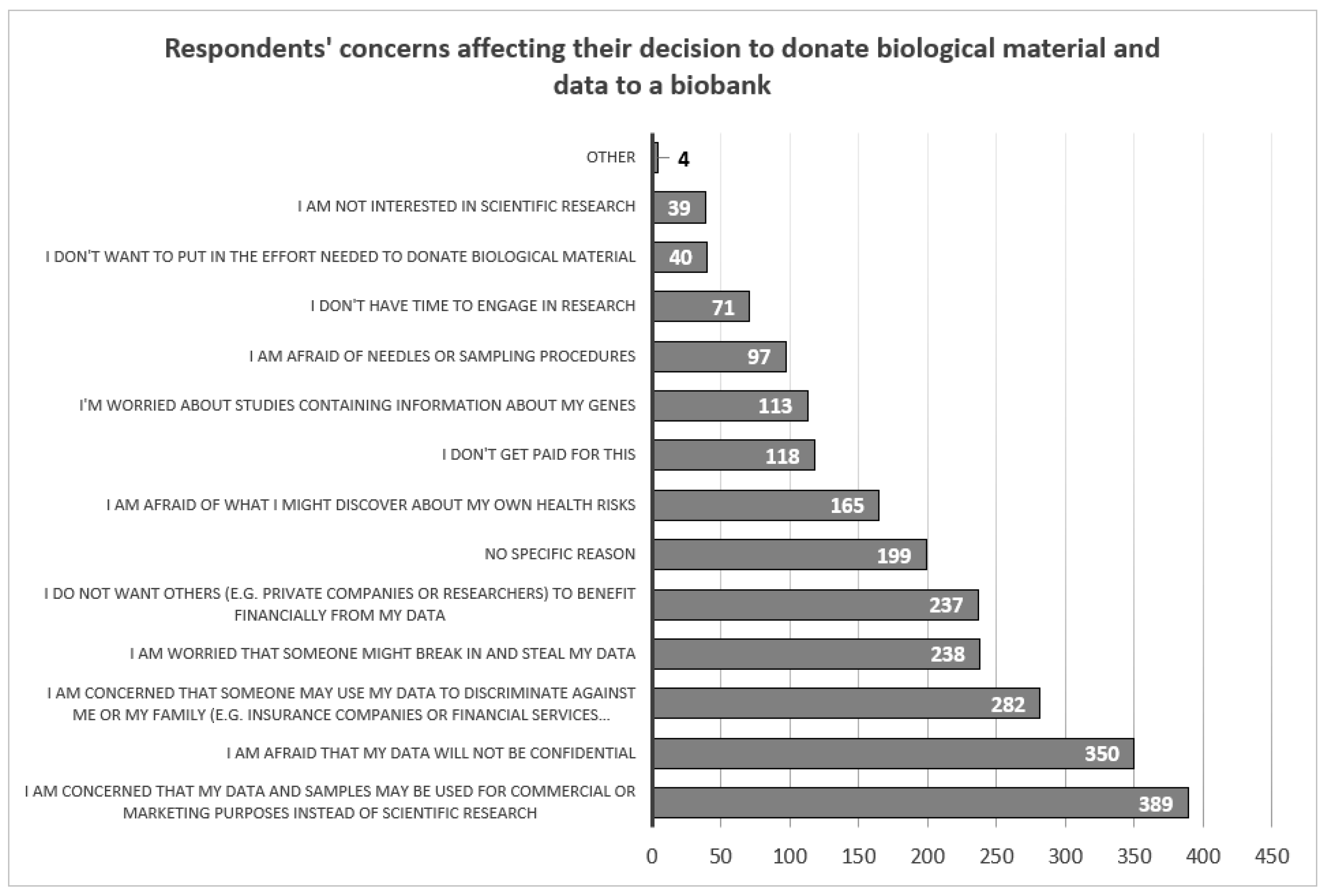

Respondents indicated that the negative factor that would most likely influence their decision was the fear that their data would be used for commercial or marketing purposes rather than for research (N=389, 37.0%). Respondents were also concerned about the confidentiality of their data (N=350, 33.3%), and that the data they provided could be used to discriminate against them or their family members (N=282, 26.8%). Factors such as lack of time (N=71, 6.7%), the effort involved in submitting biological material (N=40, 3.8%) or general interest in scientific research (N=39, 3.7%) influenced least the decision to take part in the study (

Figure 4).

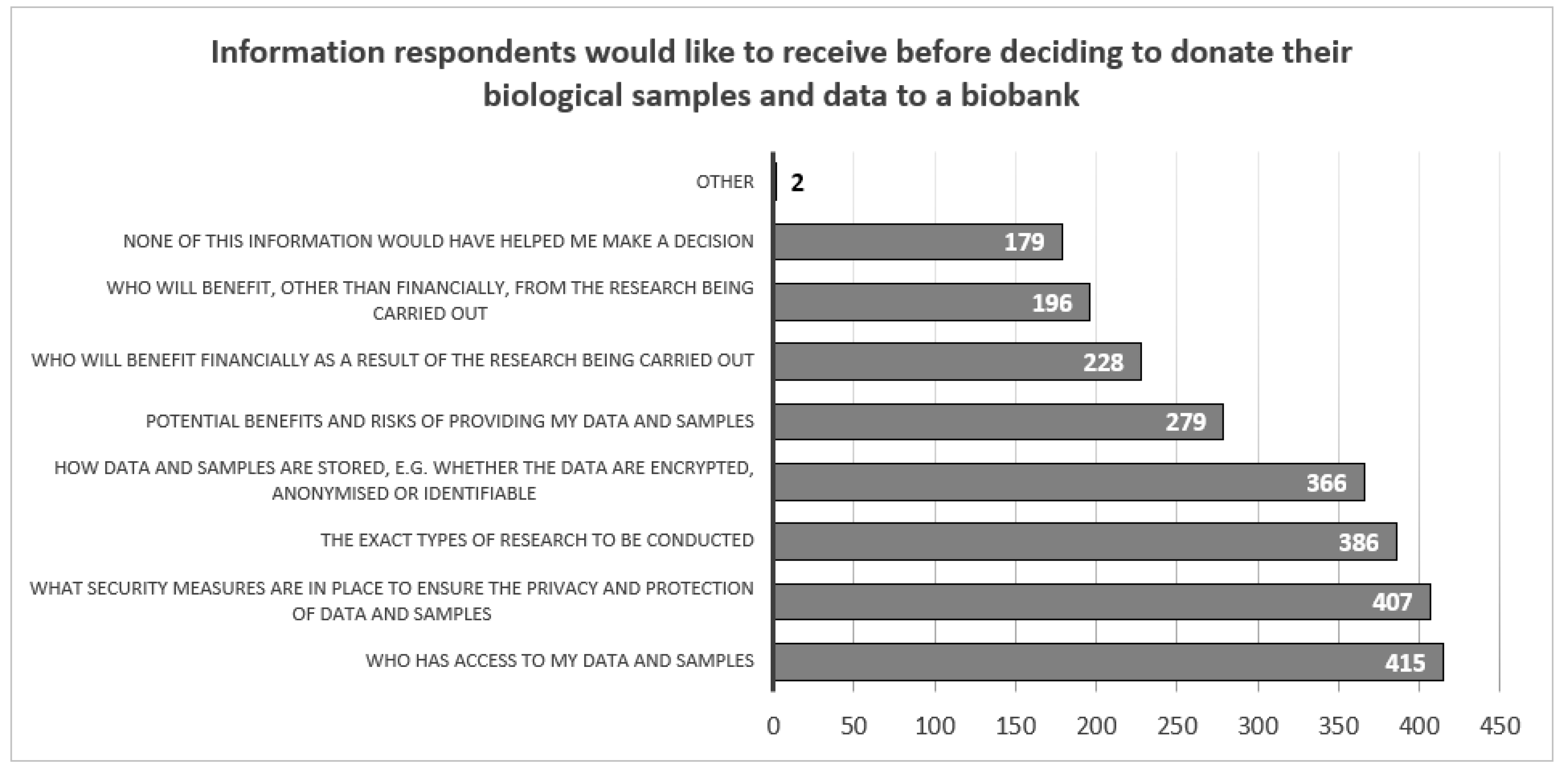

Respondents considered the most important information needed to make a decision from their perspective to be who will have access to their data and samples (N=415 39.4%), what security measures are in place to ensure the privacy and protection of the samples (N=407, 38.7%) and what research will be conducted using their samples (N=386, 36.7%). Respondents considered the least important information to be who will receive financial benefits as a result of the research (N=228, 21.7%) and who will receive non-financial benefits as a result of the research (N=196, 18.6%) (

Figure 5).

3.5. Expectations for research using biological material and biobanking

The majority (N=591, 56.2%) of respondents would like their samples to be stored in a coded way - allowing them to be identified if needed. Most (N=562; 53.4%) respondents would like to personally own the samples stored in the biobank, or would agree that the biobank itself should own the samples (N=330; 31.4%). Respondents completely distrust the government in this area, with only N=17 (1.6%) people indicating that the government should own the samples stored in the biobank (

Table 5).

Respondents are most trusting of their general practitioner, with N=213 (20.2%) people fully trusting and N=390 (37.1%) trusting that their general practitioner would ensure the confidentiality and protection of the data and samples stored in the biobank if they had access to them. Another group are doctors in general and scientists working at universities and public institutes, trusted by about a third of respondents. The government, pharmaceutical companies and other profit-driven global and Polish companies were not trusted by respondents. It is noteworthy that more than half of the respondents (N=581, 55.2%) completely distrust the government in the area of maintaining confidentiality and ensuring the security of data stored in the biobank (

Table 6).

According to respondents, the responsibility for the storage of samples and related data should rest with the biobank’s board of directors (N=567, 53.9%) or an independent committee of experts not associated with the biobank (N=337, 32.0%). Respondents have the least confidence in a committee composed of representatives of the public (N=155 14.7%) or a mixed committee composed of experts and representatives of the public (N=126, 12.0%) (

Table 7.)

4. Discussion

4.1. Public awareness of biobanks and scientific research during which biological material is collected.

A similar distribution of the population was presented in a survey conducted in a 2010 Eurobarometer survey on biotechnology [

4], a survey conducted in Switzerland in 2020 [

5] and Latvia in 2019. [

6]. According to the 2010 Eurobarometer survey on biotechnology, it was shown that, looking at Central and Eastern European Region, in Poland 28% of citizens had heard of biobanks, compared to 46% of Czech citizens, 34% of Slovak citizens, 34% of Lithuanian citizens and 31% of Hungarian citizens had encountered the term [

4]. The European average was 34%. In Germany, 30.8% of respondents in a 2018 survey had heard of biobanks [

7]. In a 2019 in Latvia survey this percentage was 25.8% [

6]. According to the results of this survey, 20.9% of respondents in 2023 in Poland have heard of biobanking. However, in the question on indicating the definition of biobanking, as many as 41.9% of respondents indicated that, in their opinion, biobanking is a process in which body fluid or tissue samples, genetic data and medical data (medical history, laboratory results, etc.) are collected and stored in order to better understand the state of health and the course of disease. It should also be noted that in Poland, more than 66% of respondents indicate that they have heard of scientific research in which biological material is used, and 58.3% have a positive opinion of it. In Switzerland, 71% of the public has heard of such research and more than 60% have a positive opinion of it. In Germany, 95.5% of respondents have a positive opinion about scientific research [

7]. Comparing the results obtained from the present study with those obtained by other researchers, it can be concluded that both the Polish society and other European societies have an awareness of scientific research in which biological material is collected, but are not fully aware that such material can be subject to biobanking and what this process consists of.

4.2. The approach to informed consent

Informed consent in the context of biobanking is a debated ethical and social issue. The use of classical consent (specific or narrow, i.e., consent to a single experiment with well-defined goals, risks and benefits) is not possible for objective reasons - biological samples are used in many studies by many scientists working in different locations. Therefore, new models of consent are being sought and proposed, such as general consent (refers to the process by which individuals donate their samples without any restrictions), broad consent (refers to the process by which individuals donate their samples for a wide range of an unspecified future research purpose with some restrictions), dynamic consent (the decision to participate in a study is made dynamically, in which modern information communication technologies are used to continuously inform and offer donors choices in the types of research for which their samples may or may not be used) or tiered consent (research can be divided into levels or categories, and participants can specify the types of research for which their samples will be used) [

8,

9]. Among medical school students in Saudi Arabia, 78% were aware that donating material to a biobank requires consent from the potential donor [

10]. In the United States, in Colorado, 79% of respondents believe that the researcher must obtain consent from them to collect biological material for biobanking, 11% that there is no such requirement and 10% have no opinion [

11]. In a 2010 Eurobarometer survey in Poland, 61% of respondents agreed with the use of narrow consent while 22% agreed with the use of broad consent. The European average is 67% for broad consent while 18% for narrow consent [

4]. In Latvia, in 2019, 27.4% of respondents preferred broad consent and 62.2% of respondents preferred narrow consent [

6]. In 2023 in Poland, it is shown that 58.8% of respondents believe that they must give their consent to biobank their samples, 34.2% have no opinion on this and 7.0% believe that they do not have to give their consent to biobanking. In addition, 48.0% of respondents believe that they should give their consent every time the samples they provide are to be used for a new research project only 14.2% of respondents consider a one-time consent sufficient. To complete the picture, it is worth noting that in this survey 53.8% of respondents indicated that they can withdraw consent already given and 42.1% do not know if they can make such a decision. Compared to 2010, both the number of people who accept the use of broad consent and the number of people who accept the use of narrow consent have declined in Poland. Combining this information with the fact that, compared to 2010, the number of people in Poland who have heard of biobanking has dropped, we can conclude that, overall, the level of awareness in society regarding scientific research has dropped significantly.

4.3. Willingness to participate in the study and factors affecting the decision to donate biological material

Willingness to participate in scientific research and willingness to donate biological material is reported by 83% of Finns [

12] and 78% of Swedes [

13]. In the UK, 72% of respondents agreed to donate their material for research [

14], in Germany 70.4% [

7]. Among Americans, this percentage was 69% [

11]. In contrast, among the Swiss, the percentage was 53.6% [

5] and among the Latvians 36.7% [

6]. In Poland in 2023. 65.3% of respondents agreed to take part in a survey that would biobank their biological material and information and their health status. Considering the level of knowledge of respondents regarding biobanking, the percentage of people willing to donate their biological material for biobanking is exceptionally high. It can be assumed that this is due to the high level of trust in the medical and scientific community.

Citizens of the European Union, on a roughly equal level, are ready to donate information about their genetic profile (34%), medical records (33%), blood samples (30%), samples taken during surgery (30%) or lifestyle information (24%) to the biobank [

4]. Latvians in 2019 were willing to donate blood samples (25.5%), samples taken during surgery (26.7%), genetic profile (27.5%), medical records (35.6%) or lifestyle information (25.8%) [

6]. The Swiss would be most willing to hand over their health forms (85.6%), a blood sample (84.6%) and biological samples they can collect themselves (81.6%). They would be least willing to share information from their social media (14.5%) [

5]. Saudi Arabian students would be most likely to donate a blood sample (82%), saliva (77%) or urine (70%) to a biobank [

10]. The results obtained in this study do not differ from those obtained by other researchers, in general, respondents in Poland are most willing to donate their blood sample or. samples they can collect themselves. They are not as willing to share their medical history or lifestyle information. It is also worth noting that respondents generally show a higher willingness to hand over their information than the European average.

Among students in Saudi Arabia, the most important motivating factors for donating their biological material were the opportunity to support the advancement of medical science (44%) and the opportunity to obtain health information (25%) [

10]. Among residents of the state of Colorado, the opportunity to contribute to scientific advancement (85%) and support in understanding genetics and disease risk, survival or treatment methods (72%) were identified as the most important factors influencing decisions to donate a sample to a biobank [

11]. Among Swedes, the main motivating factors for donating biological material were the opportunity to support future patients (88.7%) and personal benefit to the donor or his family (61.1%) [

13]. In the cited literature, examples related to altruistic motives predominate, so it is puzzling to see the results presented in this study where the welfare of future generations is considered by only 36.2% of respondents. In contrast, the opportunity to expand scientific knowledge motivates only 45.4% of respondents. The main motivation of respondents is the opportunity to gain personal benefits and learn something about their own health (62.6%). Comparing these groups is fraught with high risk, as altruistic attitudes may be influenced by a number of factors unrelated to the characteristics of the survey conducted, and factors such as history, education or religion. Although the motivating factors for donating biological material may vary, whether in Poland, Sweden, the United States or Saudi Arabia, the most important factors negatively influencing the willingness to donate biological material to a biobank include concerns about unauthorized use of samples or issues related to confidentiality and sample security [

10,

11,

13]. Despite such high concerns about data security, as many as 15.7% of respondents felt that data should be stored with contact information allowing for immediate identification and 56.2% of respondents indicated that they would prefer that data be stored in a coded manner allowing for possible identification rather than in a fully anonymized manner.

4.4. Public expectations for research using biological material and biobanking

In general, scientific institutions are trusted more worldwide than government or commercial or insurance companies [

8,

15,

16]. In 2010, both at the European Union level and in Poland, physicians were given the most trust in terms of access and oversight of data and samples stored in a biobank, 39% and 44%, respectively [

4]. In Latvia, in a 2019 survey in the first indication, physicians were also given the most trust (28.8%) followed by scientists (15.6%) [

6]. In the present study, the results were similar to European results, Polish society analogously trusts doctors and scientists the most. It is worth mentioning that the most trusted doctors are those whom respondents have direct contact with. In the United States, 92% of respondents would be willing to give their data to scientists, 80% to the government and 75% to commercial companies [

17], the results obtained in this study contradict them and indicate low levels of trust in public institutions and commercial companies. The likely reason for this inconsistency is the cultural, historical and social differences that exist between Poland and the United States. Puzzlingly, compared to other responses, respondents believe that a biobank should be under the supervision of a board of directors rather than a committee of experts (doctors and scientists). This represents some contradiction in terms of information as to whom respondents trust most. However, the source of this contradiction may be insufficient awareness of how biobanks operate.

5. Conclusions

In Poland, despite a relatively low level of knowledge among the public about biobanking, respondents showed a surprisingly high willingness to donate their biological material to a biobank. It can be assumed that the Polish public has a high level of trust in medical and scientific personnel working at universities and public research institutions for this reason, despite the low level of awareness, they are ready to participate in scientific research. It is also worth noting that the results indicate that the main motivation for participating in scientific research is personal or family benefits. The biggest concerns that respondents have are related to issues of access to the data they provide and the safeguards used. Researchers wishing to recruit potential donors, during the briefing, should focus on indicating what potential personal benefits such a donor may gain from donating their biological material, and should explain in detail how they intend to ensure the safety of the samples and data collected. At the national level, there is an apparent need for educational activities aimed at informing the public about scientific research with a special focus on biobanking. It is also crucial to raise awareness about the role that informed consent plays in the entire process and what rights a potential donor has. Given the low trust in the government and the pharmaceutical industry, it makes sense that the awareness-raising process should be led by the medical or scientific community.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Łukasz Pronicki, Marcin Czech, Mariusz Gujski and Natalia Boguszewska; methodology, Łukasz Pronicki, Marcin Czech, Mariusz Gujski and Natalia Boguszewska.; formal analysis, Łukasz Pronicki and Natalia Boguszewska; investigation, Łukasz Pronicki; writing—original draft preparation, Łukasz Pronicki.; writing—review and editing,.; Marcin Czech and Mariusz Gujski; visualization, Łukasz Pronicki.; supervision, Marcin Czech and Mariusz Gujski; project administration, Łukasz Pronicki ; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

On 16/01/2023, by decision No. AKBE/3/2023, the study and the questionnaire received a positive opinion from the Ethics Committee at the Medical University of Warsaw.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- EU Global Health Strategy; Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2022; pp.1-10.

- Proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on the European Health Data Space Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legalcontent/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52022PC0197 (accessed on 30.08.2023).

- Kaiser, Jocelyn. (2002). Population Databases Boom, From Iceland to the U.S.. Science (New York, N.Y.). 298. 1158-61. [CrossRef]

- Eurobarometer Biotechnology Report; 2010; pp.137-142.

- Brall, Caroline & Berlin, Claudia & Zwahlen, Marcel & Ormond, Kelly & Egger, Matthias & Vayena, Effy. (2021). Public willingness to participate in personalized health research and biobanking: A large-scale Swiss survey. PLOS ONE. 16. e0249141. [CrossRef]

- Mežinska, Signe & Kaleja, Jekaterina & Mileiko, Ilze & Santare, Daiga & Rovite, Vita & Tzivian, Lilian. (2020). Public awareness of and attitudes towards research biobanks in Latvia. BMC Medical Ethics. 21. [CrossRef]

- Bossert, Sabine & Kahrass (Knüppel), Hannes & Strech, Daniel. (2018). The Public’s Awareness of and Attitude Toward Research Biobanks – A Regional German Survey. Frontiers in Genetics. 9. [CrossRef]

- Domaradzki, Jan & Pawlikowski, Jakub. (2019). Public Attitudes toward Biobanking of Human Biological Material for Research Purposes: A Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 16. 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Master, Zubin & Campo-Engelstein, Lisa & Caulfield, Timothy. (2014). Scientists’ perspectives on consent in the context of biobanking research. European journal of human genetics : EJHG. 23. [CrossRef]

- Merdad, Leena & Aldakhil, Lama & Gadi, Rawan & Assidi, Mourad & Saddick, Salina & Abuzenadah, Adel & Vaught, Jim & Buhmeida, Abdelbaset & Al-Qahtani, Mohammed. (2017). Assessment of knowledge about biobanking among healthcare students and their willingness to donate biospecimens. BMC Medical Ethics. 18. [CrossRef]

- Rahm, Alanna & Wrenn, Michelle & Carroll, Nikki & Feigelson, Heather. (2013). Biobanking for research: A survey of patient population attitudes and understanding. Journal of community genetics. 4. [CrossRef]

- Tupasela, Aaro & Sihvo, Sinikka & Snell, Karoliina & Jallinoja, Pa & Aro, Arja & Hemminki, Elina. (2009). Attitudes towards biomedical use of tissue sample collections, consent, and biobanks among Finns. Scandinavian journal of public health. 38. 46-52. [CrossRef]

- Kettis, Åsa & Ring, Lena & Viberth, Eva & Hansson, Mats. (2006). Genetic research and donation of tissue samples to biobanks. What do potential sample donors in the Swedish general public think?. European journal of public health. 16. 433-40. [CrossRef]

- Goodson, Michaela & Vernon, Bryan. (2004). A study of public opinion on the use of tissue samples from living subjects for clinical research. Journal of clinical pathology 57.2 135-8. [CrossRef]

- Gottweis, Herbert & Gaskell, George & Starkbaum, Johannes. (2011). Connecting the public with biobank research: Reciprocity matters. Nature reviews. Genetics. 12. 738-9. [CrossRef]

- Dixon-Woods, Mary & Kocman, David & Brewster, Liz & Willars, Janet & Laurie, Graeme & Tarrant, Carolyn. (2017). A qualitative study of participants’ views on re-consent in a longitudinal biobank. BMC Medical Ethics. 18. 22. [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, David & Bollinger, Juli & Scott, Joan & Hudson, Kathy. (2009). Public Opinion about the Importance of Privacy in Biobank Research. American journal of human genetics. 85. 643-54. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).