1. Introduction

In hospitals, the process of applying architectural design is of great importance for the physical, psychological and physiological health of the individual. The impacts of the physical environment on healing and well-being have become more and more important in recent years for patients, their caregivers, and medical professionals [

1]. The first design guidelines for hospital wards were created by Florence Nightingale in her 1863 book Notes on Hospitals. They included considerations for spatial layout, materials, and color, but most importantly for the quality of the environment, where natural elements like daylight, fresh air ventilation, and heating played a key role in establishing sanitation standards [

2]. To create an environment that will enhance the patient’s quality of life, healing environments involve complicated relationships amongst practices, space, and care. Healing environments in healthcare settings aim to enhance healthcare quality and safety by utilizing evidence-based design principles and adopting a patient-centred care approach [

3]. This approach recognizes the impact of physical environments on patients’ well-being, comfort, and healing process [

4]. For this purpose, the benefits of healing design in hospitals have been well evidenced by relevant studies and experiments. These include shortening the length of patients’ stay in the hospital, accelerating the patient’s recovery time, reducing painkiller doses, and increasing the productivity of medical staff. In addition to providing patients with the most cutting-edge medical care and technology, healing environments should also provide its users—staff members, patients, and their caregivers—with psychological, emotional, and social support [

4]. However, healing environment design is universal and not only specific to hospitals, as it applies to all kinds of buildings, interiors, and other similar disciplines, such as in neurology, psychology, architecture, biophilic design, and medicine. These disciplines can work together with the concept of evidence-based design (EBD), where many academic studies focus on these concepts within the architectural literature [

5]. According to Alfonsi et al., [

6], evidence-based design (EBD) is a research-driven approach that uses scientific evidence to guide design decisions in healthcare settings. It involves incorporating findings from studies and research into the design process to create environments that promote positive health outcomes and improve patient experience. EBD considers various factors, such as the use of natural light, access to nature, noise reduction, infection control, and ergonomic design, among others, to enhance the healing environment. Roger Ulrich and colleagues conducted several experimental and quasi-experimental studies to determine the effects of healing hospitals on patients and other users [

7]. They found that the environment, such as environmental comfort, which can be physical, functional, or psychological, affects patient well-being. As a result, the decision made by the designer has an impact on patient comfort and should be considered as such [

7]. Like Ulrich, similar perspectives from different researchers have been studied through healthcare design and some EBD definitions come up from the EBD scholar of Hamilton and Watkins describes EBD as, ‘best available information from research and practice’ [

8]. Cama points out the importance of ‘The process involves reorganizing thinking, conducting thorough research, developing scientific questions and hypotheses, and testing innovative design solutions.’ [

9].

The evidence base is critical for the design of cancer care facilities, just as it is for the diagnosis, treatment, and care of cancer patients. [

10].

Therefore, EBD concept followed with the biophilic design concept to help patients to reduce stress, and improves health and well-being, especially for illnesses due to stress with the help of nature for a better restorative response. This is possible with the use of design patterns which deals with nature, design, and human biology of the physical surrounding. [

11].

Kellert in his book discusses biophilia, and biophilic design and comes to the findings within the light of studies Ulrich, Hartig, Frumkin, and others as the six dimensions of biophilic design which shapes the study indeed are; environmental features, natural shapes and forms, natural patterns and processes, light and space, place-based relationships and evolved-human nature relationship which derived from within more than 70 biophilic design attributes. [

12].

1.1. The Importance and the Study Challenge

A definition of health can be found in the prologue of the WHO constitution:

“Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” [

13]

In recent years, it has emerged in the literature the importance of hospitals needing to be carefully designed with patients and users in mind. This is even more important for cancer patients, to create an appropriate healing environment to support mood and reduce stress, affecting their health and well-being. Healthcare building facility design tries to maximize the quality of care for the patients and patient privacy through the patients’ experience [

14]. For this reason, the study focuses on cancer patients. Cancer, as a disease, plays a crucial role patient psychological well-being. Jencks who is the husband of the founder of Maggie’s Cancer Care Centre’s Maggie Keswick Jencks, has provided evidence that cancer patients can live longer when recovering within a good environment [

15]. According to the Ministry of Health statistics for cancer patients in N. Cyprus, there were around 700 cancer patients registered to the system back in time. The general number of cancer patients has reached 21000 since 1993, and 7000 were reported dead due to several types of cancer disease. The studies recorded 3633 patients during the last 5 years [

16].

When designing hospitals, the focus is often on functional efficiency, without considering the mental and spiritual well-being of patients and staff. For this reason, hospitals are typically associated with negative emotions such as fear, depression, and increased stress load, and accordingly, this creates reluctance in patients [

17]. Designing healing hospitals for cancer patients will only be possible if architects are aware of the existence of healing concepts of design. In this direction, based on the literature reviewed, Ulrich, Phiri, Bobrow, and Thomas point out that healing environment design in hospitals has the following characteristics and values: [

18,

19,

20]

Shortening hospital stays,

The great effect of exposure to nature on pain,

Increased motivation and productivity in patients and staff.

The work of biophilic design is also associated with cognitive architecture where Ann Sussman explains the relation in her studies as looking through how to design for user experience and needs for better design with understanding human behavior by using nature as a context. [

21].

All these literature data are linked to nature itself which is used as a landscape at the same time prefers to use, photo content analysis in his studies to be able to compare the landscape in different environmental conditions. The study releases the importance of perception of the view that may affect the perception of the space [

22].

1.2. Purpose and Objective of the Study

Emotions can have counter-productive effects on the immune system. Therefore, a psycho-social support design is required to prevent such feelings and aid the process of improving one’s health and well-being [

20]. The healing environment design approach is a very broad concept. Healing design applications can be found on various scales. Healing environment design takes place in many disciplines such as interior architecture, architecture, landscape design, and urban planning. This study is limited to health buildings – oncology hospitals, from various building categories according to the function in the field of architecture and interior architecture as well as environmental aspects such as; natural light, air quality, view, use of art, noise, etc. There is a significant emphasis on designing healing environments to achieve better health outcomes for patients. Cancer is the most serious disease type which can cause many malignant conditions in people. The increasing number of cases and deaths due to cancer, in n. Cyprus as in the rest of the world in the past years cause fear for many individuals. According to the statistics from the Health Ministry of n. Cyprus,

[23], the increasing number of cancer cases and the need to design care hospitals recently shows the importance of how there is a link between the environment and patient health and well-being. Therefore, this study looks into the oncology hospitals in n. Cyprus and uses a selected and accredited NHS’s AEDET and ASPECT toolkit to explore the toolkit the opportunities of in a developed country and apply it in the developing country of n. Cyprus to identify the strengths and weaknesses of the toolkit and make a recommendation for the adoption of the toolkit and whether it is applicable.

Within the scope of this strategy, newly built hospitals abroad are defined as “healing” facilities that have a positive impact on the built environment. However, there is a huge misunderstanding when it comes to designing hospital buildings. Hospitals that are built nowadays suffer from a ‘lack of soul’ of the use of contemporary materials and turn out to be like a glass box in the end. Therefore; hospital buildings end up with a modern appearance, however it does not meet the standards of either biophilic design or healing environment design even if the interior has been well planned. In this case, it can be said, that the beauty of a building is questionable whether talking about the classical definition or a modernist way. Donald Ruggles defines the aesthetic form of contemporary buildings which can be disappointing when compared to more classical buildings that affect people’s psychological cognition he brings his theory called ‘the nine square’ to fit into modern architecture as a building façade which can be divided and than fit into a tic-tac-toe board.

[24]

There is also a new topic about fracturing biophilia. Taylor, in his article published in 2021, discusses the fragmentation of the whole image into a naturistic form that resembles the aesthetic space itself. [

25] This is currently beyond the scope of the paper. This has been a statement that puts fractals into art, design, and architecture, however, this is beyond the scope of this study, and due to the criticism of the study, it may be explored more in detail as a future study.

Aside from the well-known functional complexity of healthcare facilities, there are several standards, guidelines, and requirements that architects must consider while designing hospitals. These vary from one country to the next in terms of quantity and focus. For instance, the Department of Health and NHS Estates in the UK has released a sizable number of standards and guideline documents to control and direct architects throughout the design process of healthcare facilities. [

26], Phiri [

18], in his book, discovers and categorizes EBD under four main headings; Improving compliance, improving design quality, enhancing efficiency and effectiveness, and achieving sustainability in architectural healthcare estates, where AEDET and ASPECT toolkit took place to support the argument under design quality indicator for better healthcare quality.

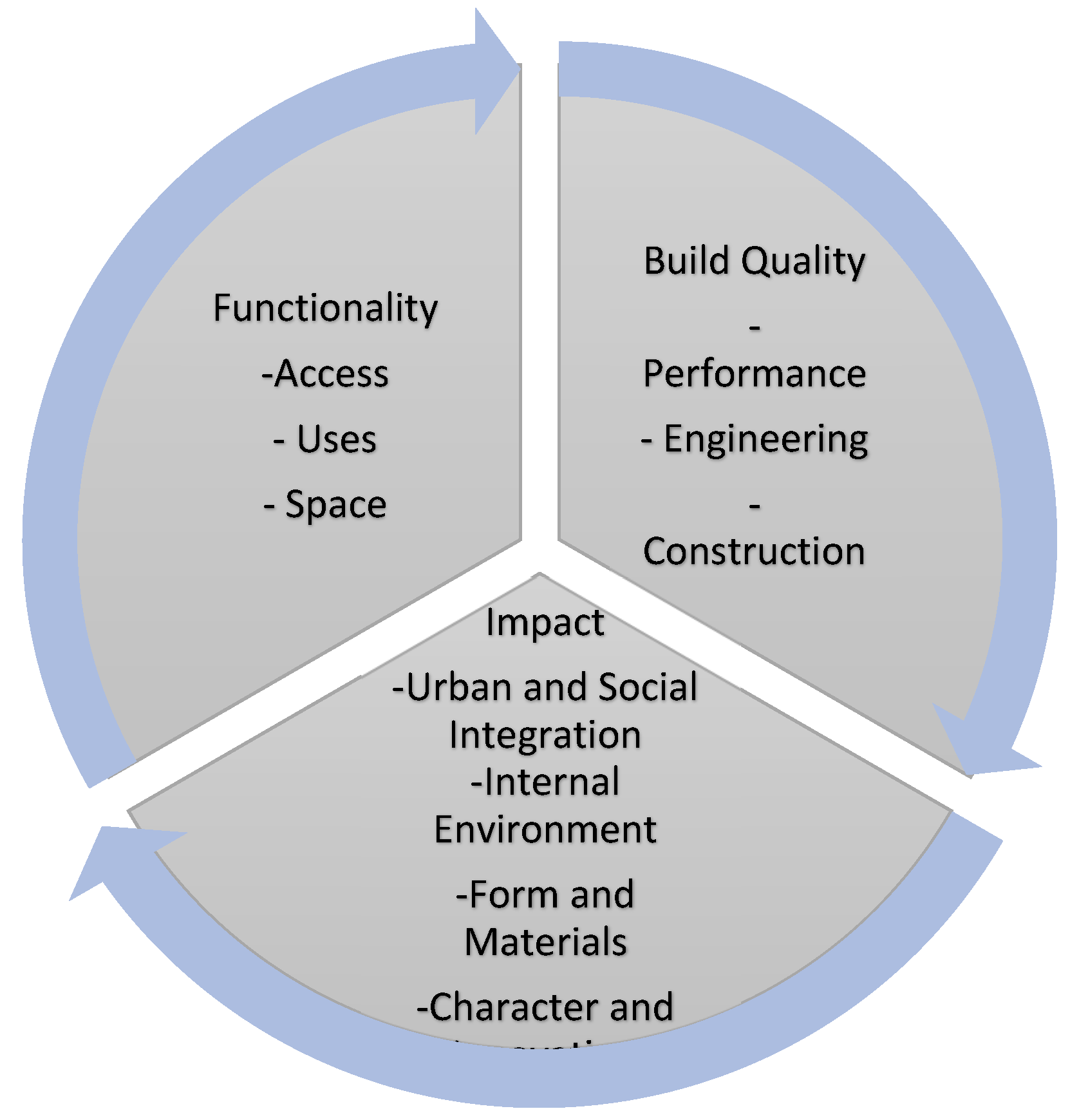

The Design Quality Indicator (DQI) if used well meets with better health outcomes. AEDET and ASPECT Toolkit are the framework derived from Design Quality Indicator (DQI) which meets under three main headings and categories; [

26], (AEDET) has a structured method for classifying each design criterion that was taken from the four NHS toolkits. The design quality indicator (DQI) is the foundation of the (AEDET). The DQI was created to assess the design quality of structures at each of the four critical stages of building development. In this study, the toolkit was used to evaluate the two oncology hospitals to check the adaptability of the toolkit within the local authorities.

There has been limited use of these toolkits in Global North countries. A handful of studies done by Ghazali, Chaham, Mahmood, et al.; explore the hospitals in Malaysia, Kurdistan, etc. [

27,

28,

29], using the AEDET evolution toolkit as an assessment method of the hospital buildings. However, none of these papers assess the toolkits nor do they provide recommendations for use in Global North countries. Although part of the study is the evaluation of the two hospitals in terms of creating a better healing environment, the main contribution of the study is the recommendations for these toolkits. AEDET is more related to professionals, aspect is more meets with the patient use. Currently, this statement makes its claim that is not supported by these data, and interviews have been included in the study. Interviews with the architects strengthen the argument.

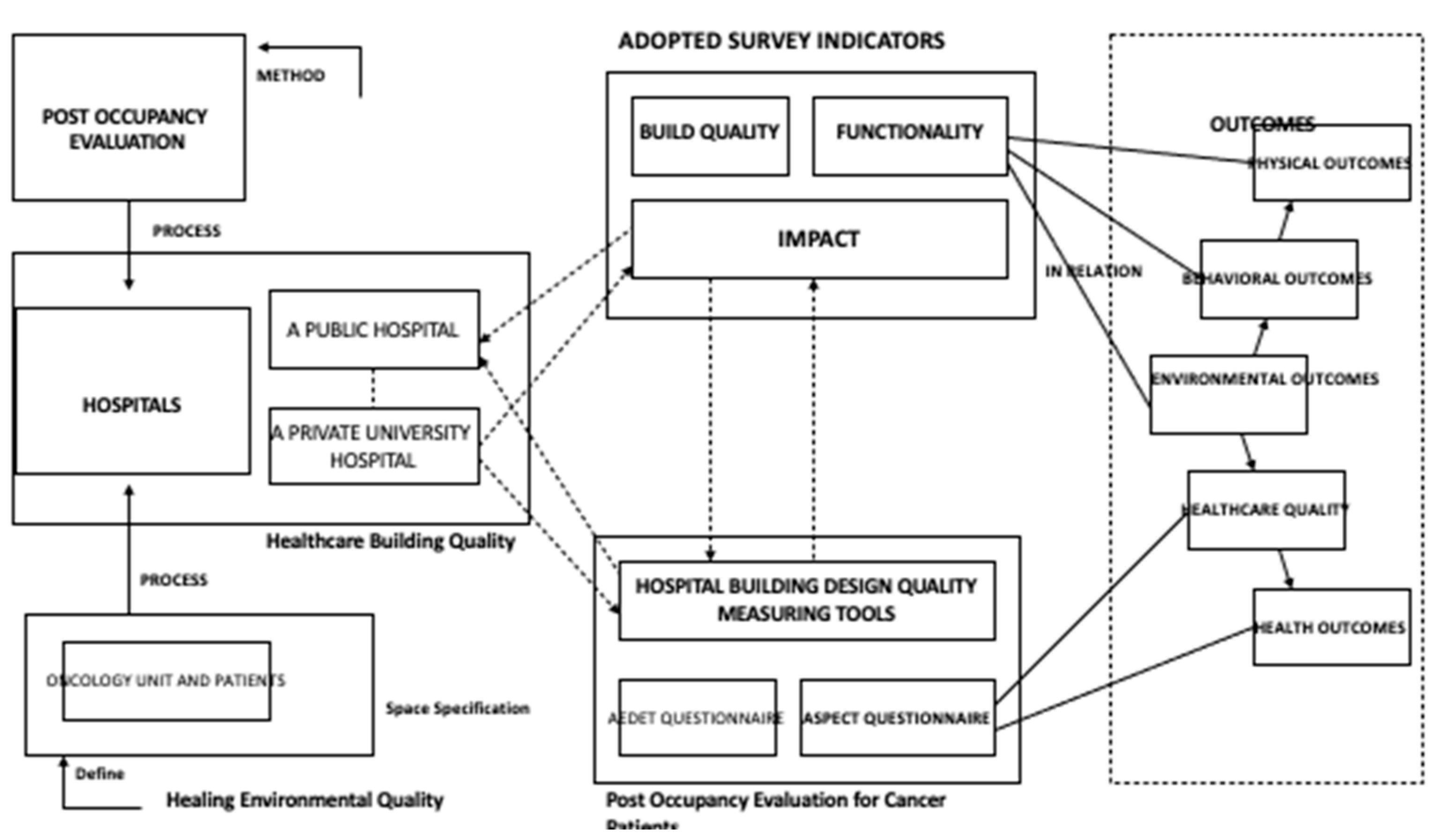

Scheme 1.

The modified framework of the NHS’s AEDET toolkit is based on the Design Quality Indicator. [

26].

Scheme 1.

The modified framework of the NHS’s AEDET toolkit is based on the Design Quality Indicator. [

26].

In this context, the aim is to investigate the concept of evidence-based design, patient-centred design in terms of the healing environment in hospitals, to examine the cancer hospitals in n. Cyprus through the use of an existing toolkit and create recommendations based on how this toolkit developed for developed countries can be used in developing contexts too. This is achieved by employing the evaluation toolkits across two oncology hospitals in n. Cyprus.

Research indicates that access to nature, daylight, and wellness factors can reduce drug use and hospital stays. Nature positively impacts patients’ emotions, reduces anxiety, and stimulates senses. Natural environments and design can improve health by balancing contrast and harmony. [

30].

At the Center for Health Design, an organization that supports healthcare and design professionals to improve the quality of healthcare through evidence-based building design, researchers have proposed the definition of EBD as: “the process of basing decisions about the built environment on credible research to achieve the best possible outcomes” [

31].

Scientific evidence is used to improve the effectiveness of design interventions and gain the support of healthcare providers trained to rely solely on sound scientific data. This new scientific approach to the design of healing environments is generally referred to as ‘evidence-based design’ [

32]. The primary potential uses of the instruments are measuring the facility design to develop the existing surroundings [

33], devising updated hospital buildings, and offering a quantitative method for evaluating a built structure for research [

34].

This study focuses on finding a relevant existing toolkit to evaluate the link between nature, human comfort, and well-being to create healthy and sustainable spaces that enrich daily lives through the use of Evidence-based Design, Patient-Centred Care Design in terms of environmental comfort. The main purpose of the study is to raise awareness about the role of architecture, guidance, and biophilic design in interacting with the healing environment in the healing process of cancer patients. In addition, it is to develop criteria and design guidelines for the implementation of cancer design practices in hospitals in n. Cyprus and to fill the gap in the literature in this context.

1.3. Study Framework

The study aims “to draw attention to the role of architecture in the interaction with nature and its elements in the healing process of patients, to develop criteria and design guidelines for the application of healing environment design in hospitals in n. Cyprus”.

For evaluating facilities, there are numerous techniques and resources. The technical building performance, function/usability, or form/beauty are often the three areas of concern. However, assessments of active structures are uncommon. They are regarded as a drawn-out and expensive portion of the last stage of a construction project. As a result, the mistakes made during completed construction projects are not recorded. For this, mixed methods including both qualitative and quantitative approaches were used. Procedures include collecting, observing, analyzing, and comparing both qualitative and quantitative data in terms of primary and secondary data.

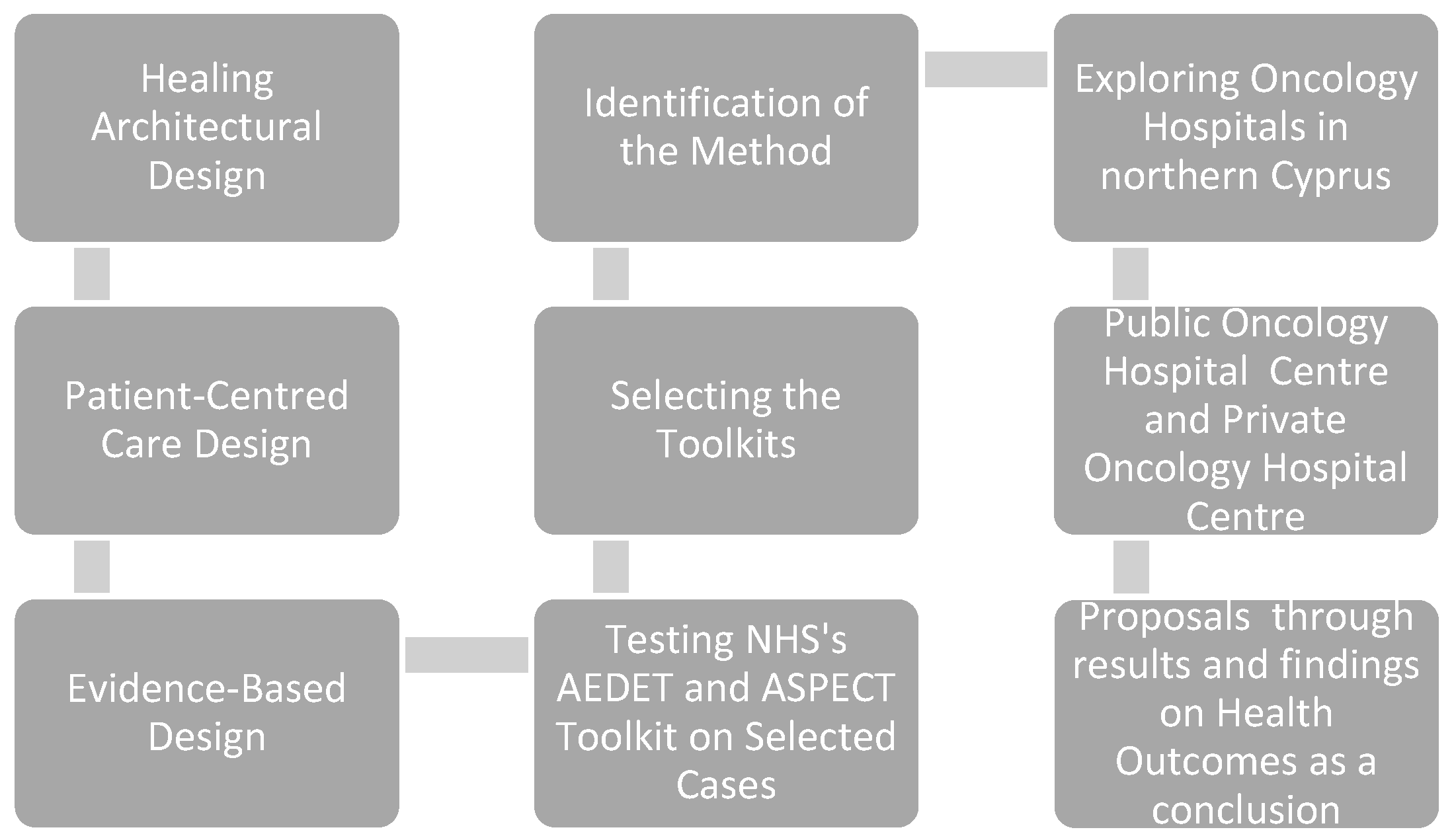

In general, the study framework process proceeded as follows: A targeted literature search and data collection on the concept of evidence-based design, patient-centred care design, and biophilic design research was conducted. Healing environment design literature and theories have been carefully studied to define guidelines. A targeted literature search and data collection process were carried out on evidence-based design in hospitals. To establish the analysis method of hospitals, a pilot analysis study was conducted on hospitals with selected toolkits. Existing oncology hospitals in n. Cyprus were researched. First of all, different hospitals were examined in the selection of the study hospitals. At this stage of the study, various information and documents regarding qualitative and quantitative sources were collected and individual interviews were conducted with some professionals such as; architects, engineers, stakeholders and doctors. The number of existing oncology hospitals in n. Cyprus has been identified and architectural studies and AEDET and ASPECT evaluation toolkits were applied. A comparison has been made between public and private hospitals to test the validity according to their strengths and weaknesses, and a proposal for a new healing design for hospitals has been developed in line with the findings. The results and recommendations section have provided a design guide proposal based on all research and analysis.

Scheme 2.

The study framework.

Scheme 2.

The study framework.

General hospital samples were examined in the field study carried out to examine the architectural space quality in oncology units. In the study; Public Hospital, Oncology Center, and Private Hospital, Oncology unit were selected as the study areas. When selecting the hospitals, the criteria were considered that the institutions to be examined are public and private hospitals, which are assumed to have more favorable spatial conditions, are preparing for accreditation, and have intensive surgery departments, hence the importance of patient rooms and their service life is long. In the course of the study and data analysis, hospitals are referred to as (A) and (B) hospitals without being named.

The study focused on patient experience in healthcare facilities to recognize the deficiencies within this context. As such, it was required to rethink the patient experience within healthcare facilities and create new guidelines, which can be applied in other Global South countries worldwide.

POE is possibly the most well-known as an assessment method for evaluating the quality of buildings by users. ‘Post-occupancy’ refers to the building already being in use at the time of evaluation. In other words, POE can be described as progress for assessing facilities in a more defined and systematic way after the completion and the use of the building [

34].

AEDET is a toolkit used for assessing the design quality of buildings within the healthcare sector. It creates a detailed report demonstrating the strengths and weaknesses of the inspected design [

26].

A Staff-and-Patient Environment Calibration Toolkit (ASPECT) supports the AEDET evolution toolkit to evaluate the design quality of spaces of hospitals for healthcare staff and their patients [

35].

At the Center for Health Design, an organization that supports healthcare and design professionals to improve the quality of healthcare through evidence-based building design, researchers have proposed the definition of EBD as “the process of basing decisions about the built environment on credible research to achieve the best possible outcomes” [

31]. Scientific evidence is used to improve the effectiveness of design interventions and gain the support of healthcare providers trained to rely solely on sound scientific data. This new scientific approach to the design of healing environments is generally referred to as ‘evidence-based design’ [

36].

According to Ulrich [

37], only the physical surrounding is healing for the patients supportive for the families, and efficient for the staff can be the result of design successfully. To sum it up, evidence-based design has provided scientific justification for deep-rooted notions of the importance of the physical environment for health and healing.

Healthcare building design frequently involves complex concepts, which are difficult to measure and evaluate. The Achieving Excellence Design Evaluation Toolkit (AEDET) is a questionnaire tool, which is used with post-occupancy evaluation to evaluate the quality of the healthcare buildings to understand their strength and weaknesses. AEDET evaluates a design by posing a series of clear, non-technical statements, based on three key criteria: Functionality, Build Quality, and Impact. [

26].

To achieve this guidance, the evaluation method in the United Kingdom National Health System (NHS) accredited Achieving Excellence Design Evaluation Toolkit (AEDET) was used for the patients and caregivers. [

26].

On the other hand, ASPECT; staff and patient environment is a complementary tool that is used alongside AEDET for the staff of the hospital. [

35]. In the end; radar table formation was achieved based on the results and findings separately for the selected cases of one private hospital building which is the Oncology Unit of Near East University Hospital and the public Oncology Centre of Public Hospital which is based at the capital city, Nicosia.

The Methods employed for data collection were UK’s NHS AEDET Evolution and ASPECT Evaluation Toolkits Questionnaires, personal site observation, and photographic documentation supplemented by the toolkits’ evaluations. [

21].

The AEDET (Achieving Excellence Design Evaluation Toolkit) Evolution is part of a benchmarking tool that assists in measuring and managing the design quality in healthcare facilities. In terms of reliability, it includes references to evidence-based design literature and this is related to the criteria used in the evaluation. In terms of validity, its use is mandatory in the major hospital design development of n. Cyprus. It evaluates a design through a series of statements that encompass the three areas. The Impact Area deals with the degree to which the building created a sense of place and contributed positively to the lives of the users and its neighbors. It involves four sections - Character and Innovation, Form and Materials, Staff and Patient Environment, and Urban and Social Integration. The Build Quality Area deals with the physical components of the building rather than the spaces and involves three sections – Performance, Construction, and Engineering. The Functionality Area deals with issues on the primary purpose of the building and involves three sections – Use, Access, and Space as follows; [

26].

Table 1.

AEDET Questionnaire Modified Table Aspects with Numbers in detail. [

26].

Table 1.

AEDET Questionnaire Modified Table Aspects with Numbers in detail. [

26].

| AEDET EVOLUTION |

CRITERIA |

LAYERS |

| IMPACT |

- A.

talic>A. Character and Innovation

|

A.01. There are clear ideas behind the design of the building and grounds.

A.02. The building and grounds are interesting to look at and move around in.

A.03. The building, grounds, and art design contribute to the local setting.

A.04. The design appropriately expresses the appropriate values.

A.05. The project is likely to influence future healthcare designs. |

|

B.01: The design has a human scale and feels welcoming.

B.02. The design contributes to the local microclimate, maximizing sunlight and shelter from prevailing winds.

B.03. Entrances are obvious and logical, about likely points of arrival on site.

B.04 The external materials and detailing appear to be of high quality

B.05: The external colours and textures seem appropriate and attractive.

B.06. The design maximises the site opportunities and enhances a sense of place |

|

C.01: The design respects the dignity of patients and allows for appropriate levels of privacy and company

C.02. The design maximises opportunities for daylight/views of greenery or natural landscape.

C.03. The design maximises opportunities for access to usable outdoor space.

C.04. There are high levels both of comfort and control of comfort

C.05. The design is understandable and wayfinding is intuitive.

C.06. The interior of the facility is attractive

C.07. There are good baths/toilets and other facilities for patients.

C.08. There are good facilities for staff, including convenient places to work and relax without being on demand. |

|

D.01: The height, volume, and skyline of the design relate well to its setting.

D.02: The facility contributes positively to its locality.

D.03: The hard and soft landscapes contribute positively to the locality

D.04: The design is sensitive to neighbors and passers-by. |

| BUILD QUALITY |

|

E.01: The facility is easy to operate

E.02: The facility is easy to clean and maintain.

E.03: The facility has appropriately durable finishes and components

E.04: The facility will weather and age well.

E.05: Access to daylight, views of nature, and outdoor space are robust.

E.06: The design maximises the opportunities for sustainability. |

|

F.01: The engineering systems are well-designed, flexible, and effective.

F.02: The engineering systems exploit any benefits from standardization and prefabrication where relevant

F.03: The engineering systems are energy efficient.

F.04: There are emergency backup systems that are designed to minimize disruption.

F.05: During construction disruption to essential healthcare services is minimised. |

|

G.01: If phased construction is necessary the various stages are well organised.

G.02: Temporary construction work is minimised

G.03: The impact of the building process on continuing healthcare provision is minimised

G.04: The building and grounds can be readily maintained

G.05: The construction is robust

G.06: The construction allows easy access to engineering systems for maintenance

G.07: The construction exploits any benefits from standardization and prefabrication where relevant |

| FUNCTIONALITY |

|

H.01: The prime functional requirements of the brief are satisfied

H.02: The design facilitates the care model

H.03: Overall the design is capable of handling the projected throughput.

H.04: Workflows and logistics are arranged optimally.

H.05: The design is sufficiently flexible to respond to enable expansion.

H.06: Where possible spaces are standardized and flexible in use patterns.

H.07: The design facilitates both security and supervision. |

|

I.01: There is good access from available public transport including any on-site roads

I.02: There is adequate parking for visitors and staff cars with appropriate provisions for disabled people

I.03: The approach and access for ambulances are appropriately provided.

I.04: Service vehicle circulation is good and does not inappropriately impact the experience for service users and staff

I.05: Pedestrian access routes are obvious, pleasant, and suitable for wheelchair users and people with other disabilities/impaired sight

I.06: Outdoor spaces wherever appropriate are useable, with safe lighting indicating paths, ramps, steps, and fire egress.

I.07: Active travel is encouraged and connections to local green routes and spaces are enhanced. |

The AEDET Toolkit is divided into three main categories Impact, Build Quality, and Functionality which look at the aspects of; A; Character and Innovation, B; Form and Materials, C; Staff and Patient Environment, D; Urban and Social Integration, E; Performance, F; Engineering, G; Construction, H; Use, I; Access, J; Space. The criteria under aspects also numbered as A.01-5, B01-6, C.01-6, D.01-4, E.01-6, F.01-5, G.01-7, H.01-7, I.01-7 and J.01-6. [

26].

The ASPECT (A Staff and Patient Environment Calibration Toolkit) measures the manner the healthcare environment can impact both the satisfaction levels of patients and the provision of facilities to staff. It evaluates eight sections - Privacy, Company and Dignity; Views; Nature and Outdoors; Comfort and Control; Legibility of Place; Interior Appearance; Facilities; and Staff. In terms of reliability and validity, the ASPECT is based on a database of over 600 pieces of research. The ASPECT Evaluation, in the form of questionnaires, assessed users’ satisfaction with both nurses and patients. An overall total of 50 staff, 20 professionals including architects, engineers, and stakeholders, and 150 cancer patients will respond to the questionnaires as follows; [

35].

Table 2.

ASPECT Questionnaire Aspects with Numbers. [

21].

Table 2.

ASPECT Questionnaire Aspects with Numbers. [

21].

| ASPECT |

ASPECT CRITERIA |

LAYERS |

| C: Staff and Patient Environment |

C1: Privacy, company, and dignity |

1.01: Patients can choose to have visual privacy.

1.02: Patients can have private conservations

1.03: Patients can be alone

1.04: Patients have places where they can be with others

1.05: Toilets/bathrooms are located logically, conveniently, and discretely. |

| C2: Views |

2.01: Spaces where staff and patients spend time have windows.

2.02: Patients and staff can easily see the sky.

2.03: Patients and staff can easily see the ground.

2.04: The view outside is calming.

2.05: The view outside is interesting. |

| C3: Nature and Outdoors |

3.01: Patients can go outside.

3.02: Patients and staff have access to usable landscaped areas.

3.03: Patients and staff can easily see plants, vegetation, and nature. |

| C4: Comfort |

4.01: There is a variety of artificial lighting patterns appropriate for day and night and for summer and winter.

4.02: Patients and staff can easily control the artificial lighting.

4.03: Patients and staff can easily exclude sunlight and daylight.

4.04: Patients and staff can easily control the temperature.

4.05: Patients and staff can easily open windows/doors.

4.06: The design layout minimizes unwanted noise in staff and patient areas. |

| C5: Legibility of Place |

5.01: When you arrive at the building, the entrance is obvious.

5.02: It is easy to understand the way the building is laid out.

5.03: There is a logical hierarchy of places in the building.

5.04: When you leave the building, the way out is obvious.

5.05: It is obvious where to go find a member or staff.

5.06: Different parts of the building have different characters |

| C6: Interior Appearance |

6.01: Patients’ spaces feel homely.

6.02: The interior feels light and airy.

6.03: The interior has a variety of colors, textures, and views.

6.04: The interior looks clean, tidy, and cared for.

6.05: The interior has provisions for art, plants, and flowers.

6.06: The ceilings are designed to look interesting.

6.07: Patients can have and display personal items in their own space. 6.08: Floors are covered with suitable material. |

| C7: Facilities |

7.01: The bathroom has seats, handrails, non-slip flooring, a shelf for toiletries, and somewhere to hang clothes within easy reach.

7.02: Patients can have a choice of bath/shower and assisted/unassisted bathrooms.

7.03: There is a space where religious observances can take place.

7.04: There is a place where live performances can take place.

7.05: There is a place where live performances can take place

7.06:Patients have facilities to make drinks.

7.07:There are accessible vending machines for snacks.

7.08:There are facilities for patients’ relatives/friends to stay overnight. |

| C8: Staff |

8.01: Staff have a convenient place to change and securely store belongings and clothes.

8.02: Staff have convenient places to concentrate on work without being in demand.

8.03: There are convenient places where staff can speedily get snacks and meals.

8.04: Staff can rest and relax in places segregated from patient and visitor areas

8.05 All staff have easy and convenient access to IT.

8.06 Staff have convenient access to basic banking facilities and can shop for essentials

8.07: The design facilitates both security and supervision |

The ASPECT Toolkit is taken from the C criteria of the AEDET Evaluation Toolkit as Staff and Patient Environment and opens up to eight aspects: C1.1-5; Privacy, company and dignity, C2.1-5; Views, C3.1-3; Nature and Outdoors, C4.1-6; Comfort, C5.1-6; Legibility of Place, C6.1-8; Interior Appearance, C7.1-8; Facilities, and C.8.1-6; Staff consequently. [

35].

1.4. Case Study Setting

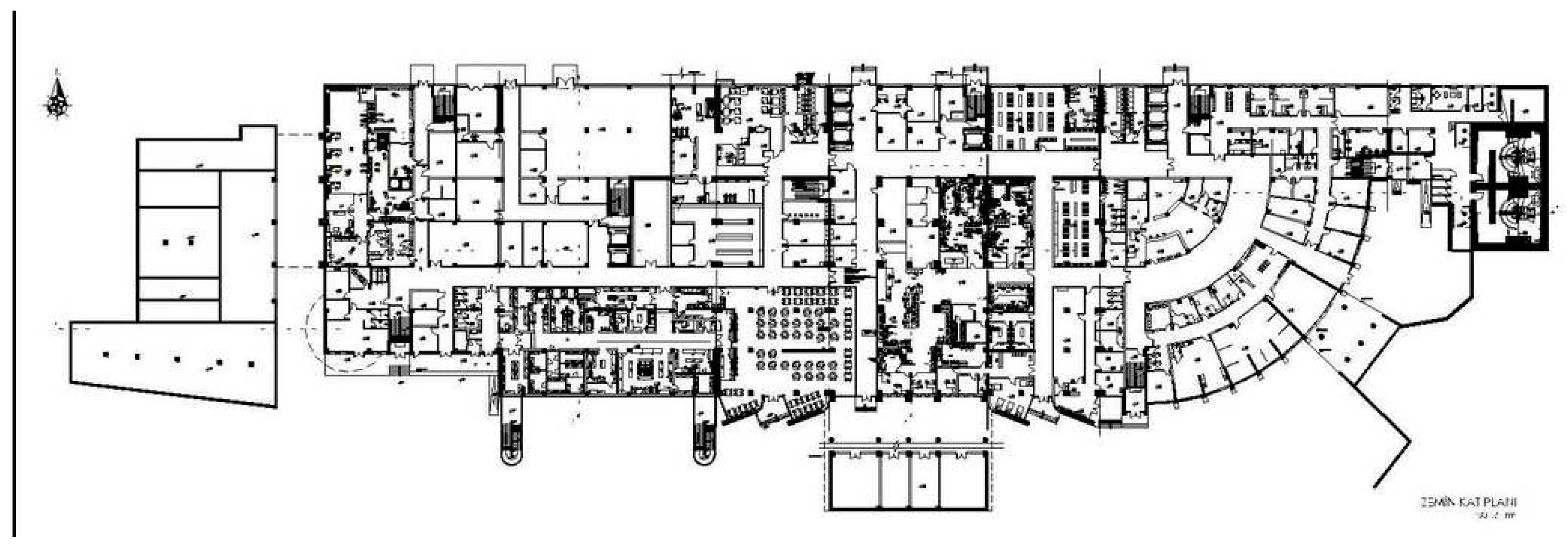

1.4.1. Hospital A; A Public Central Hospital’s Oncology Centre

Public Central Hospital’s Oncology Centre is cancer–oriented centre established in 2016 and aims to provide global healthcare standards for cancer patients and promote their psychology in a new, technically, and physically developed suitable environment. [

38]. There are 62 beds and 5 intensive care beds in the 6-story Oncology Center with a total capacity of 67 beds.

Figure 1.

Typical Functional floor plan for the oncology center.

Figure 1.

Typical Functional floor plan for the oncology center.

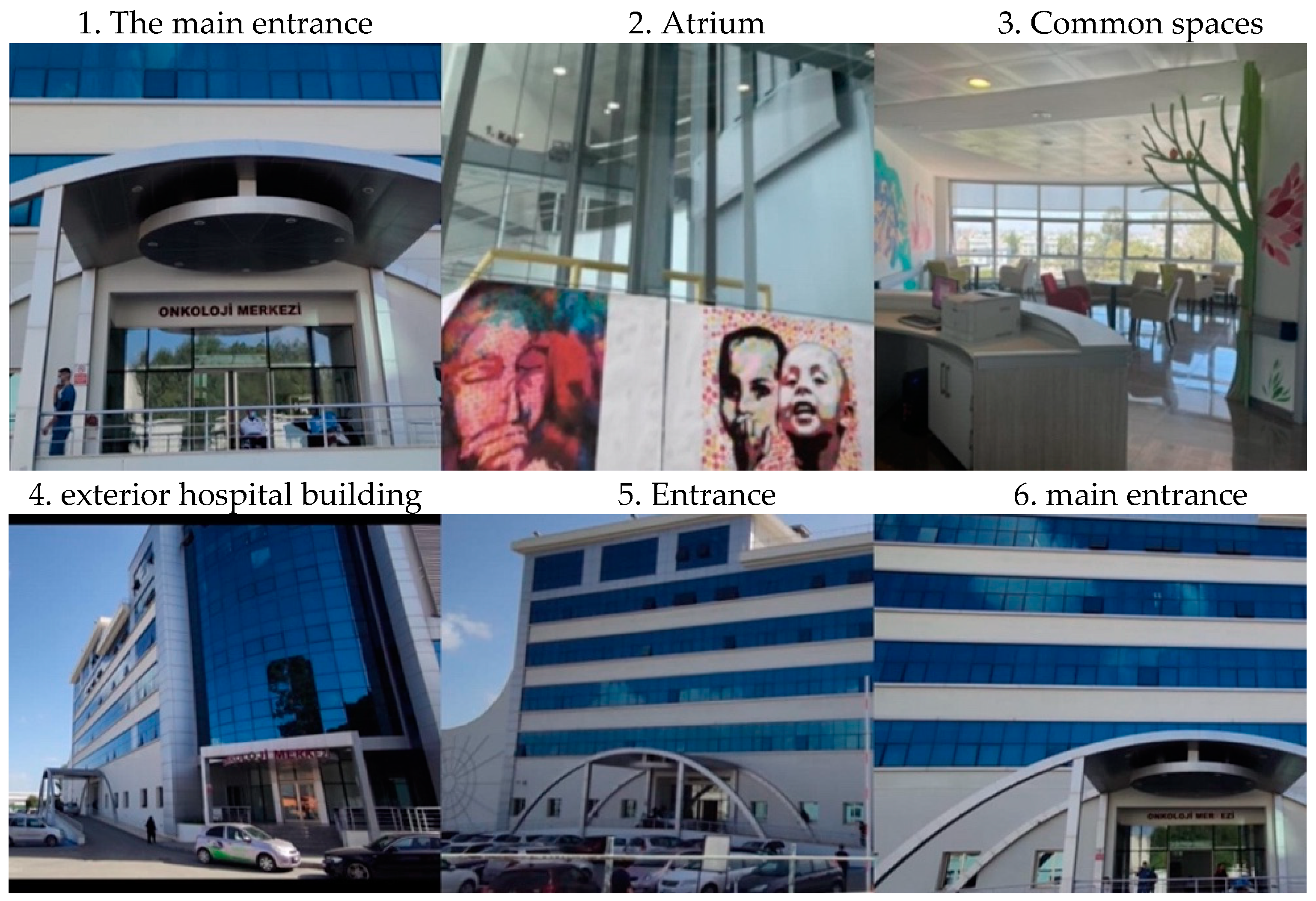

Figure 2.

Public Oncology Hospital, Nicosia. .

Figure 2.

Public Oncology Hospital, Nicosia. .

1.4.2. Hospital B: Private Hospital Oncology Unit

The hospital is composed of three separate blocks including several entrances to the accommodation unit for the patients and relatives. The main entrance is segregated from the other entrances to prevent public and private relationships. The hospital proposes specific entries for staff and service facilities. The emergency department also provides another entry to the facility which has a connection to the outpatient department to ease the travel distance between the departments.

Three separate blocks are as follows. Nine floored main central blocks are offering inpatient care. The floored East Block is built for emergency services. Three floored West Blocks are for healthcare services. The floors are connected with a vertical circulation system.

The hospital is comprised of more than 200 single-patient rooms, 8 operational surgical spaces with contemporary equipped for operation, monitoring, and anesthesia as well as Neonatal Intensive care units, Intensive care Units where a laboratory is located near the Radiotherapy, Nuclear Medicine, and Radiotherapy centers to provide faster and most accurate results in diagnosis, scanning and treatments fort he, cancer patients. [

39].

Figure 3.

Typical functional floor plan of the hospital.

Figure 3.

Typical functional floor plan of the hospital.

Figure 4.

Private Near East University Hospital from left to right.

Figure 4.

Private Near East University Hospital from left to right.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Research Design

2.1.1. Data Analysis

The primary method used in evaluating healthcare facilities within this study is the application of the existing toolkits of AEDET and ASPECT. The methodological framework below, applies the AEDET and ASPECT toolkits in two different oncology hospitals, in order a) to evaluate and compare the main criteria of build quality, functionality, and impact on health outcomes; and b) create a revised assessment method based on the findings that can be used by architects designing hospitals in Global North contexts, such as in n. Cyprus. The decision about the number of people was made in collaboration with the Cancer Research Centre and based on similar numbers from other related studies.

The methodology was compromised of ;

Literature review

Comparative analysis between two hospitals

Testing AEDET and ASPECT toolkits as questionnaires in these hospitals amongst patients, relatives and staff.

Semi-structured interviews with architects

Personal building observations

Photo content analysis

Results have been shown as tables in numeric and charts as comparison.

The research took place both in the oncology units of Private Hospital and Central Hospital’s Oncology Centre. The main focus was on patients’ perceptions through their experiences in the hospital.

Due to the pandemic period of COVID-19, considerable delays were observed in securing the necessary permission necessary permissions. Once approved all recommended COVID-19 protection precautions were taken and the in-person questionnaire process would be more appropriate and relevantly parallel to the studies as well as provide a more practical.

The questionnaire data were entered into Google Forms and done with different profile groups of users of the building consisting of:

- 150 Cancer patients and relatives above 18 years old. (75 per each hospital)

- 50 Doctors and staff. (25 per each hospital)

- 20 Professionals such as architects engineers and stakeholders.

The questionnaire is selected to be used due to the relevance to the study in terms of observation, environmental, functional, and behavioral aspects of the building as well as focusing on the patient’s needs. The key aspects have been used as the main framework, under the main themes, however, the questions were selected and modified according to the reasons decided.

Scheme 2.

Methodological Framework for the study.

Scheme 2.

Methodological Framework for the study.

3. Results

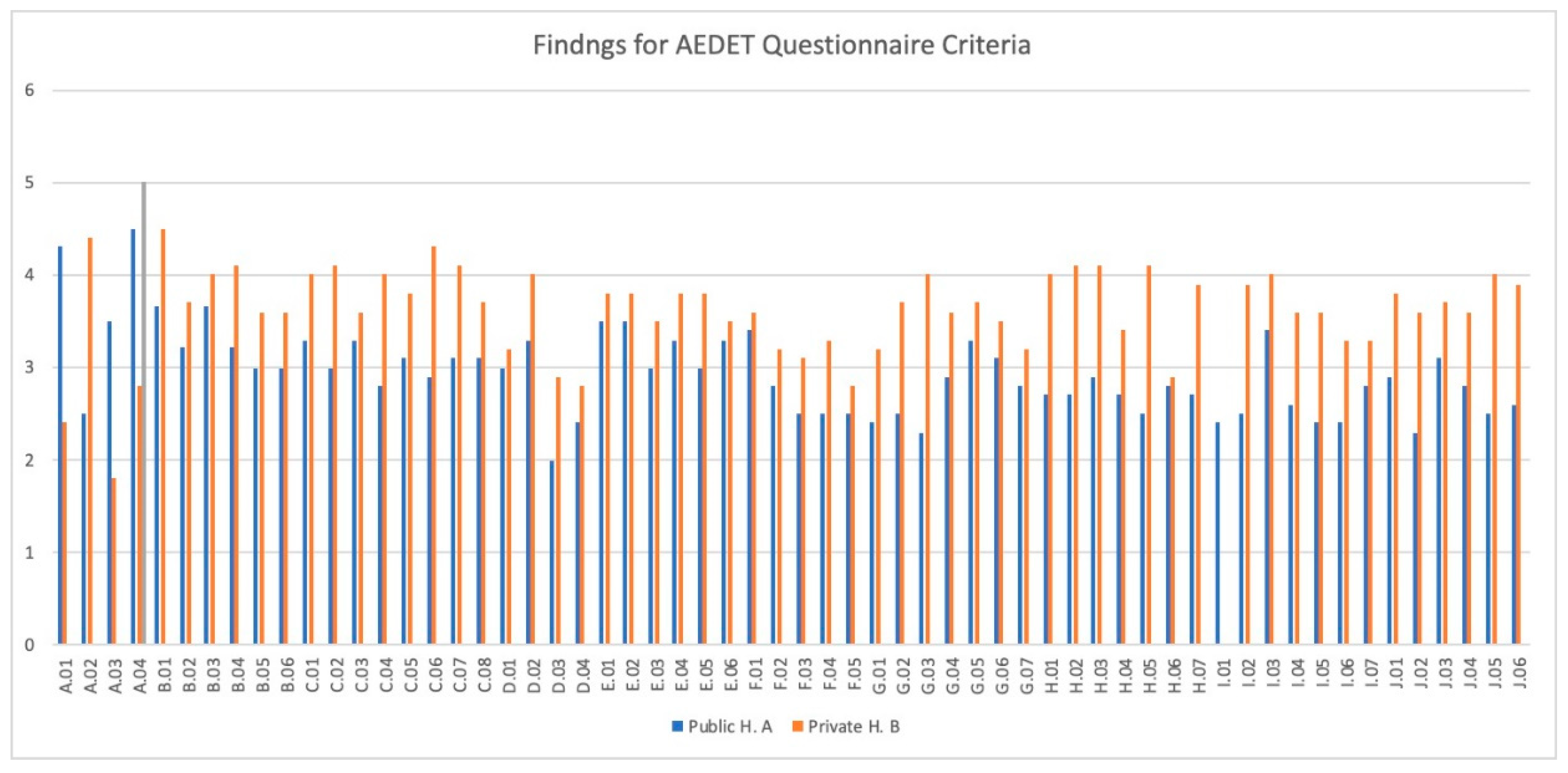

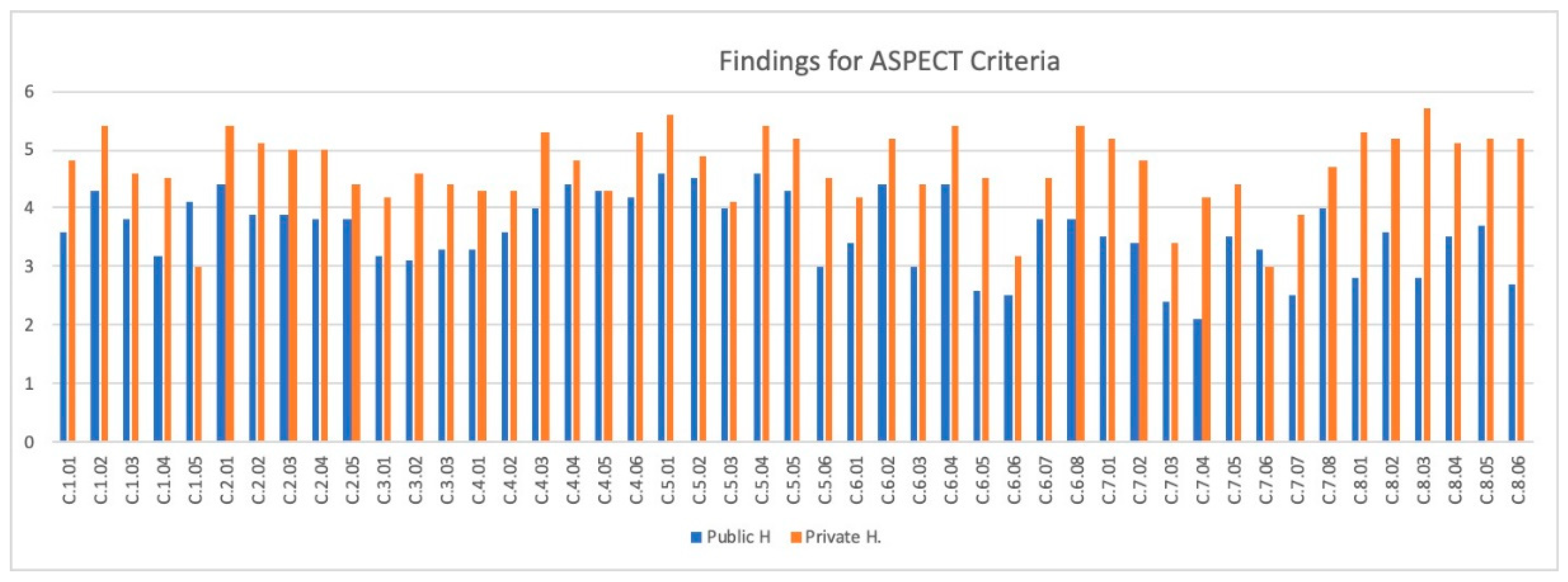

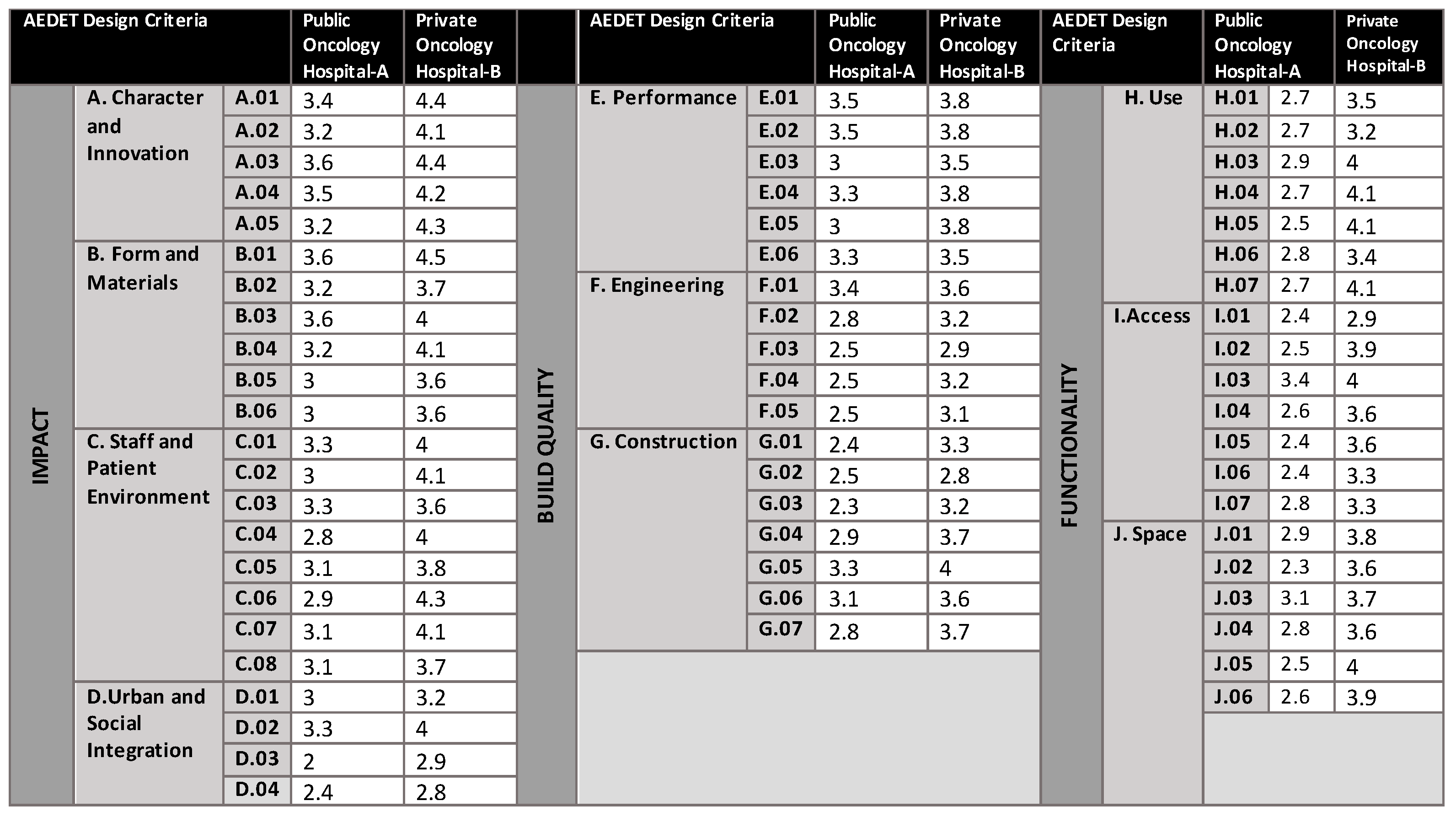

3.1. AEDET Toolkit findings

The comparative approach was used, and the results were shown with the radar tables to evaluate selected cases together and make new suggestions in global standards for future healthcare architecture in n. Cyprus. The table presented below provides a comprehensive overview of the AEDET Criteria across ten distinct categories. The table includes the previously mentioned point allocations for each criterion. Additionally, the table presents a comparative summary of the overall results, quantified on a scale of 1 to 6. The AEDET evaluation highlights that the aspects related to public hospitals tend to fall below average, particularly in terms of functionality. While there isn’t a significant disparity between the build quality and impact aspects for both public and private hospitals, a noteworthy distinction emerges when considering functionality. This divergence underscores a substantial difference in this particular aspect between the two types of hospitals.

3.2. Comparative Case Study Findings Between Hospitals

Studies revealed, that they have not been evaluated before, and evaluation toolkits are not enough to be used. The main gap is that the toolkits are not fully appropriate to use in the global south and need to be modified and this is the contribution to the field.

Northern Cyprus, similar hospital designs, challenges, not fit for purpose and needs to be modified. Developed and developing. Examples need to be supported. Current toolkit studies, what they look like. The current toolkit it’s not fit for purpose and it needs modification which deals in the study. They have been designed for developed country context instead of developing country context. the other studies include.. talking about hospitals, not the tools they used. There is a handful of studies that used these tools beyond the global north context but they haven’t discussed the shortcomings of the toolkit and they haven’t proposed. This is the first paper to discuss, the shortcomings of the toolkits and what needs to be added or changed.

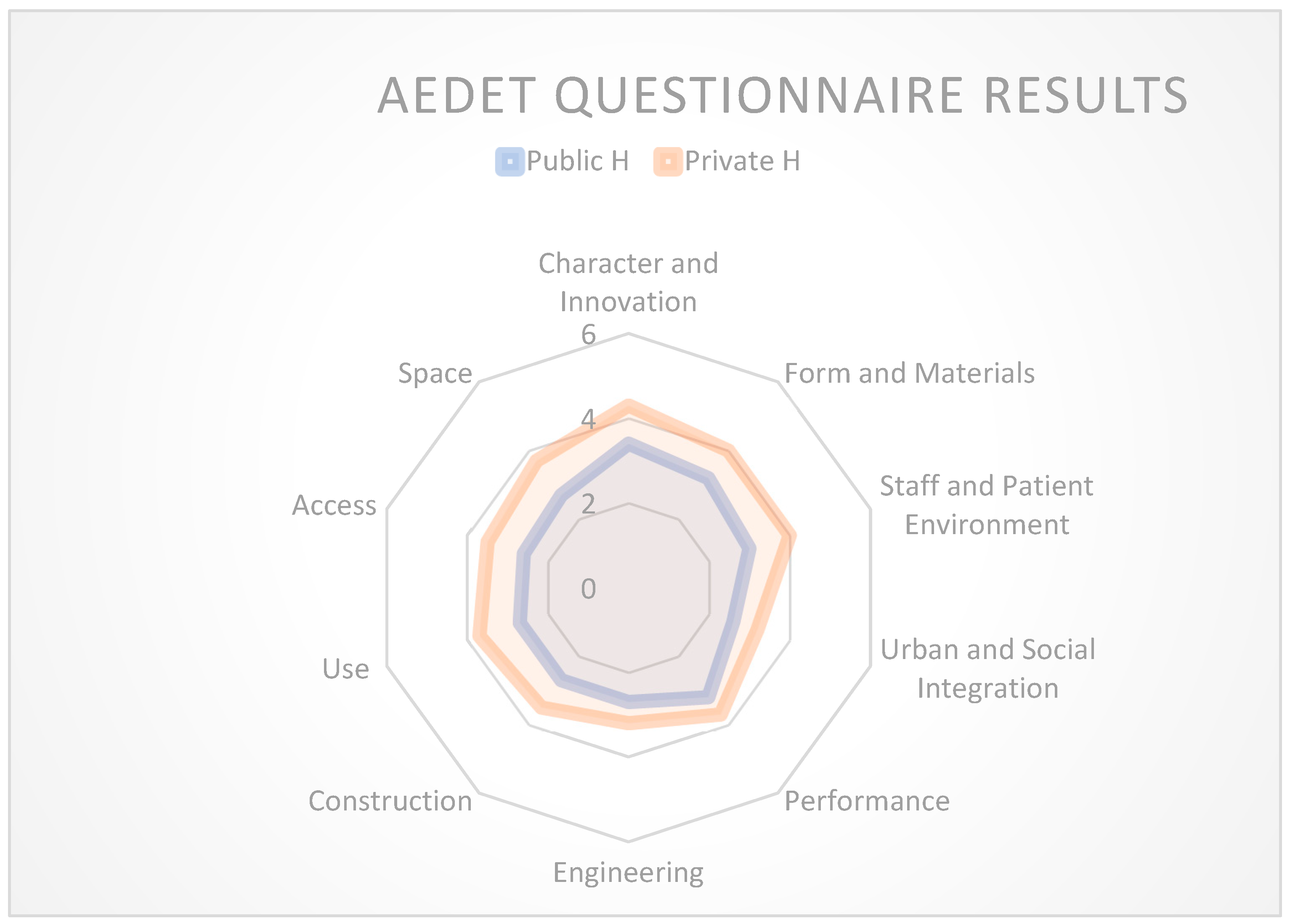

Based on the data presented below, it is evident that private hospitals exhibit a higher score in comparison to public hospitals in terms of scoring. This disparity is particularly pronounced in terms of their distinct characteristics and innovative practices. However, the variation in building performance between the two categories is comparatively marginal.

Chart 1.

Findings Table for Comparing the Hospitals Examined Within the Proportions of the AEDET Design Parameters.

Chart 1.

Findings Table for Comparing the Hospitals Examined Within the Proportions of the AEDET Design Parameters.

Based on the findings in the

Table 4, bar chart has been made to follow the comparison and figuring the strengths and weaknesses of the toolkit to be more legible.

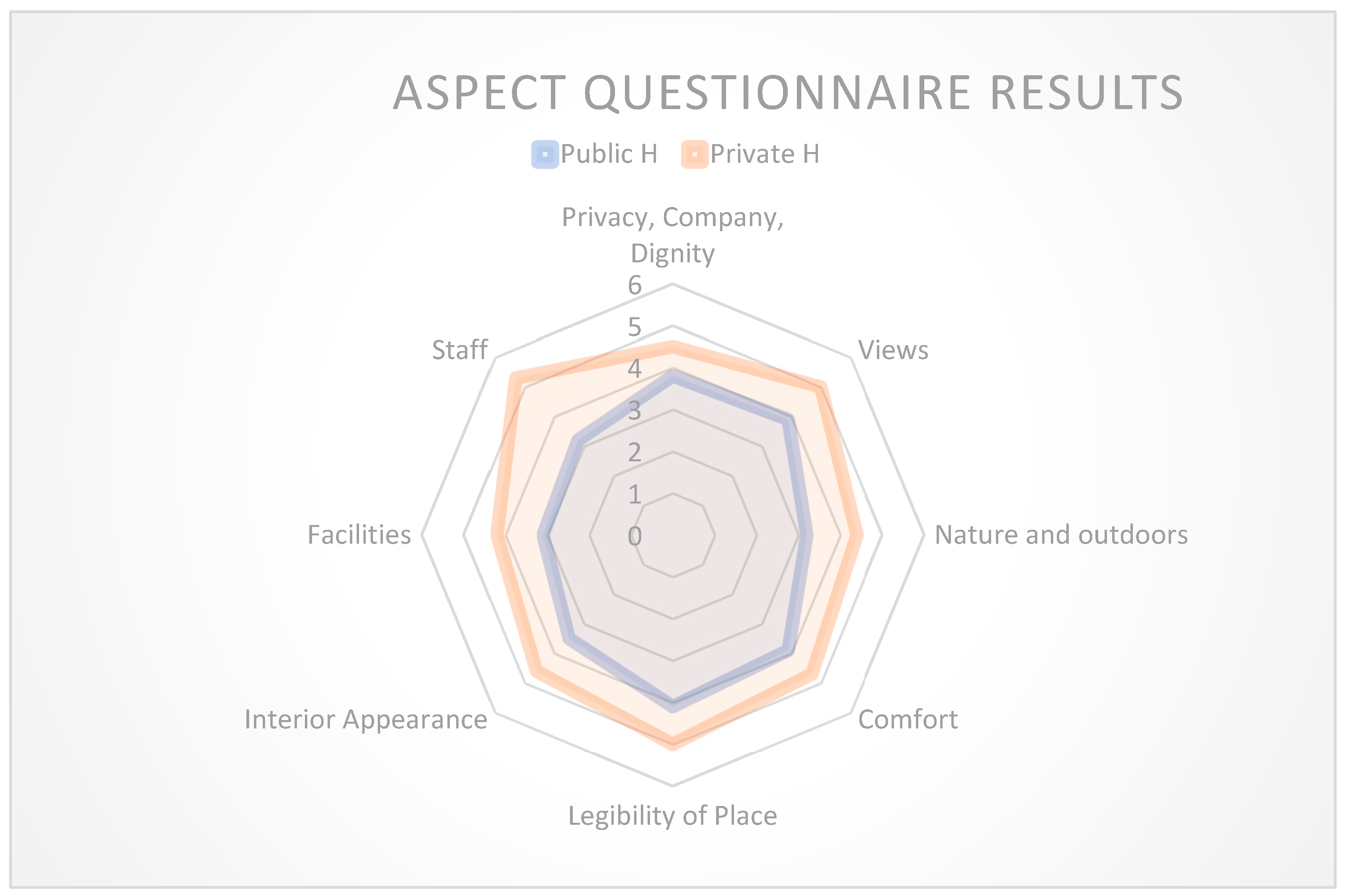

The radar table has been made below to show the comparison and the findings above more clearly in between Public and Private Hospitals.

Chart 2.

Clear comparison between hospitals for AEDET.

Chart 2.

Clear comparison between hospitals for AEDET.

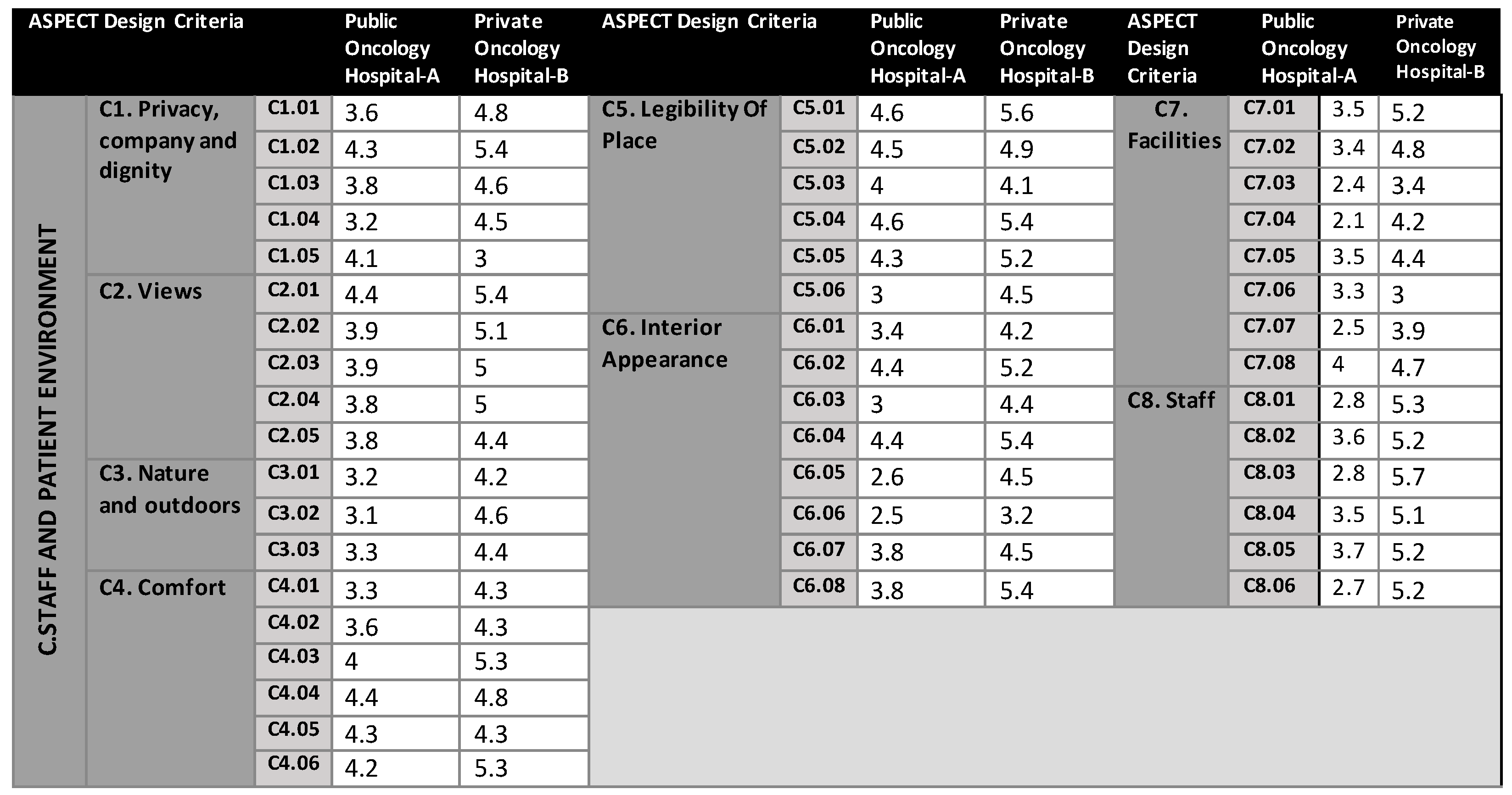

3.3. Findings for Data Analysis Method ASPECT Toolkit

The overall results and mean comparison of the ASPECT questionnaire shown above are in between the scoring of 1-6 where 1 is virtually no agreement, 2 is hardly any agreement, 3 is little agreement, 4 is a fair agreement, 5 is strong agreement and 6 is virtually complete agreement. Below are the main findings and comparisons made amongst the ASPECT criteria for public and private hospitals. The comprehensive assessment indicates that both hospitals are situated at an intermediate level in terms of their overall performance. Notably, the aspect displaying the most pronounced vulnerability pertains to “Facilities” (c07), garnering a rating of 2.5 out of 6. This outcome suggests an inadequacy in the provisions extended to users within the public hospital context. Conversely, this same aspect yields a notably higher rating of 3.9 out of 6 for the private hospital, denoting a relatively more satisfactory arrangement of user-oriented facilities. The facet reflecting the most robust outcome pertains to the “Legibility of Place,” wherein the public hospital secures a commendable score of 4.6 out of 6, and the private hospital excels with a score of 5.6 out of 6, affirming the effective navigational and comprehensible attributes of both establishments.

3.4. Comparative Case Study Findings Between Hospitals

Chart 3.

Findings Table for Comparing the Hospitals Examined Within the Proportions of the ASPECT Design Parameters in detail.

Chart 3.

Findings Table for Comparing the Hospitals Examined Within the Proportions of the ASPECT Design Parameters in detail.

Based on the findings in the

Table 5, bar chart has been made to follow the comparison and figuring the strengths and weaknesses of the toolkit in detail to be more legible.

Chart 4.

ASPECT QUESTIONNAIRE – Staff and Patient Environment Comparison Radar Table .

Chart 4.

ASPECT QUESTIONNAIRE – Staff and Patient Environment Comparison Radar Table .

The radar table has been made below to show the comparison and the findings above more clearly in between Public and Private Hospitals.

The radar table effectively underscores a distinct contrast between the private and public hospitals. Notably, “Staff Experience” emerges as a salient forte for the private hospital, while conversely ranking as the least prominent aspect for the public hospital. In the realm of user experience, the element of “Comfort” emerges as a pivotal determinant. This encompasses a spectrum ranging from lighting, air quality, and views to design layout, window provision, and temperature control. The collective impact of these factors cannot be overstated. It is noteworthy that user feedback uniformly converges on a specific observation: the inability to open windows, attributed to safety concerns. This convergence underscores a shared constraint experienced by users across both hospital types.

4. Discussion

The findings from the AEDET and ASPECT evaluation provide valuable insights into the current state of healing environment design in the selected hospitals in northern Cyprus. By analyzing the results through the lens of relevant literature and theory, key linkages and implications emerge surrounding environmental design, user experience, and the need for localized design toolkits.

4.1. According to Data Analysis Results for AEDET Toolkit

The following table has been made through the results of the table for the AEDET toolkit. The comparison has been made through each aspect of each hospital.

In essence, Zeisel’s conceptual study and the AEDET evaluation share a common ground in their recognition of the intricate interplay between environmental design, occupant health, and well-being. They reinforce the idea that a well-thought-out environment can have a profound impact on occupants’ physical and psychological health, highlighting the importance of conscientious design decisions in healthcare settings.[

40].

The goal in healthcare environments is to create nurturing, home-like spaces for patients that prioritize patient-centered care. This can be achieved by optimizing the design to provide access to nature, maximize natural light through large windows, reduce noise with single-bed patient rooms and outdoor healing gardens, and use calming natural colors. Technology integration is also important for sustainability. Proximity to nature is a key element in designing healing spaces, with factors like daylight, ventilation, tranquility, and natural colors being consistent considerations in hospital design [

41].

Environmental factors significantly impact building designs, including healthcare facilities. However, there is often a lack of consideration for these factors in healthcare facility planning. To enhance patient health and wellness, it is essential to integrate natural settings, establish visual connections with nature, and create therapeutic healing gardens. The use of natural light and color can elevate environmental quality standards, leading to faster patient recovery [

42].

-Patient rooms must be designed to create a homely, attractive environment that contributes to patient well-being and faster recovery. Therefore, in stationary rooms and waiting areas, attention should be paid to the use of natural light, natural materials, and textures, as well as artistic objects [

43].

The following factors need to be considered by management to practice patient-centred care Design:

The location of the building, the selection of the place with the city centre

Contextual design principles

The functional relationship of efficient and appropriate interior spaces

Easy signs for in-hospital navigation

Suitably designed and accessible structures for all people [

44].

4.2. According to Data Analysis Results for ASPECT Toolkit

Table 7.

Discussion of ASPECT QUESTIONNAIRE Results.

Table 7.

Discussion of ASPECT QUESTIONNAIRE Results.

| ASPECT CRITERIA |

Discussion through Results |

| C1.’Privacy, company and dignity’ |

Patient privacy decisions, private conversations, being alone, and having places to be with others are higher in value when compared with the public oncology center. However, only toilets/bathrooms located logically are chosen to be more successful in the public oncology center. Overall, Private hospitals have better privacy, company, and dignity recognition compared to the Public Oncology Center. |

| C2.’Views’ |

Natural view, time spent having windows, seeing the sky, seeing the ground, outside calming view, outside interesting view is nearly as reachable to the highest standards in the private hospital oncology unit. On the other hand, an obvious difference is observed in the decrease of values in Public H. Oncology Center where the location and the view are still on the average but not more than the Private Hospital. |

| C3.’Nature’ |

Connection with nature and the outdoors needs to be studied further by providing more access to the existing landscape or creating a landscape for the users to feel more engaged with nature itself. In this sense, a public hospital oncology center is very poor in terms of providing a natural environment as well a Private Hospital oncology unit can be developed to be better. |

| C4.’Comfort’ |

In terms of comfort, the findings were almost close to each other with a slightly more successful private hospital oncology unit. Patients and staff can easily control temperature and patients and staff can easily open windows and doors are quite equal for both hospitals which needed to be taken into consideration again. |

| C5.’Legibility of Place’ |

The legibility of space especially different parts of the building has different characteristics and is not at the level of standards in the public oncology center. However, the entrance definition, exit definition, and finding related staff are near the complete agreement for the private oncology unit. The hierarchy of places is almost the same and could be better in terms of, a patient needs to go to the upper levels to find the treatment rooms, it could be located closer to the entrance area. |

| C6.’Interior Appearance’ |

Interior appearance definition is more successful in private oncology units where usage of suitable floor materials is successful, hygienic, application of art plants and flowers is not applied for the units but in general hospital usage was adequate. In both hospitals, the ceiling design was not successful and below limits. Unfortunately, Public Hospital appearance needs to be revised according to the standards which could be more flexible, sustainable, and easy to clean by providing more character to the interior design. |

| C7.’Facilities’ |

The facilities are the poorest aspects of all the factors. Providing spaces for religious activities, live performances, and snacks again failed to pass the average in public oncology centers. The points in private hospital units look more successful however, it could be better in providing facilities to make drinks, and even if there is a religious room the users do not know about it to make religious activities. |

| C8.Staff |

Staff is the section where the most difference had in between both hospitals. Private H. Oncology unit is nearly to complete agreement and highest standards for the staff, however, on the other hand, the poorest results were obtained for Public Oncology Center found for the staff by having only nurse stations in the middle but no resting rooms provided for them. |

4.3. Recommended Design Criteria Checklist

The table below summarises the results and discussion under the main categories of functionality, build quality, and impact, the following recommendation checklist has been made to adapt the AEDET and ASPECT toolkits to improve the use of hospitals in northern Cyprus.

Table 8.

Recommended and adapted checklist for northern Cyprus.

Table 8.

Recommended and adapted checklist for northern Cyprus.

| Recommended Design Criteria Checklist for Oncology Hospitals based on the AEDET and ASPECT Toolkit Aspects and Findings in northern Cyprus |

| 1 |

According to FUNCTIONALITY |

− Create a more sustainable hospital environment

− Promote healthier environments

− Develop patient experience surveys

− Provide sustainable design for increasing building performance

− Improve patients’ health and well-being by applying evidence-based design

|

| 2 |

According to BUILD QUALITY |

− Select the location of the building near the city center

− Apply site-specific design principles

− Use appropriate interior spaces to provide a functional relationship

− Use easy and simple signs for hospital navigation

− Provide accessible suitably- designed structures for all people

− The design facilitates the care model

− Arrange workflows and logistics optimally

− Handle the projected throughput capable for the overall design

|

| 3 |

According to IMPACT |

− Make the style respect the dignity of patients and permit applicable levels of privacy and company

− Maximize the opportunities for daylight/views of the natural landscape

− Maximize the opportunities for access to the usable outside area

− Measure high levels of comfort and management of comfort

− Make wayfinding apprehensible

− Provide an appropriate square measure for a sensible bath/bathroom and different facilities for patients.

− Provide sensible facilities for staff together with convenient places to relax together with indoor and outdoor areas

− Provide use of natural daylight − Use of thermal comfort

− Good air ventilation

− Use of artworks and plants

− Monitoring noise

− Providing infection control

|

The recommended checklist made above is derived from the combined insights of the AEDET evaluation and ASPECT Toolkit analyses. It outlines key design criteria for creating effective and patient-centered oncology hospitals in northern Cyprus. By considering these recommendations, hospitals can work toward providing healing environments that align with both functional and human aspects of healthcare design.

5. Conclusions

This paper explored the potential of using the AEDET Hospital Evaluation Toolkit to create better healing environments for cancer patients beyond the Global North context, with a focus on hospitals in northern Cyprus. The healing environment is crucial for cancer patient’s well-being and recovery, yet current hospital designs in the Global South often neglect these considerations. The study explored and analysed two different healthcare facilities in Nicosia, Northern Cyprus mainly consist of the same characteristics as each other such as; one public oncology hospital, and one private oncology department of a university hospital. The profile of the users for these hospitals has been explored generally, however, the profile for the patients has been focused on short-term illnesses who have experienced a stay in hospital for at least one night. The patient’s ages were categorized as above 18 according to the adult age characteristics. Surveys were prepared to provide and receive data from the patients, staff, and relatives within the themes of physical, environmental, and behavioral characteristics formed from different functions from the general scale, followed by the building scale and room scale.

The study focused; on the physical, and psychological characteristics of the spaces however; it does not include technical standards.

Human-environment interactions are intricate and entail personal characteristics in addition to social, cultural, and behavioral difficulties. [

45] It is seen that the definitions of disease and health have changed many times in the evolution from the first hospital buildings in history to today’s hospital structures, and many advances have been made in medical science. [

46].

The AEDET evaluation indicates a positive shift in the physical qualities and design direction of hospitals, aligning to create healing environments. [

27]. However, this improvement does not appear to correspond with the levels of satisfaction reported by end users, as revealed in the ASPECT analyses.

This incongruity emphasizes the intricate relationship between design evolution and user experience, prompting a need to address both physical and subjective aspects to ensure the creation of genuinely satisfying healing environments for N. Cyprus. The toolkits used in the evaluation processes ensure good quality in the development process, assuming they have been tailored to specific cases. Otherwise, they are inadequate. Thus, providing architects with a ‘modified local’ checklist toolkit as an assessment method will help design better quality and qualified healthcare facilities. As Pantayou et al. in their article on Cyprus “ This study is one of a few focusing on Cyprus. It considers a relatively long period and updated the previous evidence in the literature regarding heat-related morbidity”. This study also proves the development in terms of the importance of healthcare buildings on people’s health and well-being in Cyprus.[

47]

Through a mixed methods approach involving literature review, case studies, surveys, and interviews, the study evaluated two oncology hospitals in northern Cyprus using the NHS-accredited AEDET toolkit and ASPECT questionnaires. Findings revealed the strengths and weaknesses of the hospitals regarding environmental comfort, privacy, views, facilities, and other design aspects affecting patient experience. The comparative analysis found private hospitals performed better overall, especially in functionality criteria.

However, a key finding was that the AEDET toolkit in its current form is not fully fit for purpose in the Cyprus context, requiring adaptations to be applicable in the Global South. The toolkit was designed for developed countries and lacks considerations for local climate, culture, regulations, materials, and other contextual factors. This paper is the first to critically analyze the limitations of AEDET for developing countries and propose targeted modifications to improve its relevance.

Based on the evaluation results and findings, the study put forth a recommended design criteria checklist adapted for hospitals in northern Cyprus. The adapted criteria integrate learnings on privacy, access to nature, wayfinding, staff facilities, and other aspects affecting patients and staff. This localized criteria checklist serves as a practical tool for architects to design healthcare facilities aligned with user needs, promoting quality care. The approach can be extended to other Global South settings.

The study is limited in its focus only on two hospitals in Nicosia, involving a small sample of patients, staff, and professionals. Additionally, the scope centers on physical and environmental qualities, without considering other technical standards. Further research across more hospitals and regions would strengthen the findings.

The localised design criteria put forth can guide hospital design in n. Cyprus and other developing nations to better support patient health. The findings highlight the need for toolkit modifications to suit local contexts, paving the way for further refinements. The approach can be replicated to evaluate and tailor toolkits for diverse settings.

This work has broader implications for hospital design worldwide. It emphasizes that while evidence-based design principles are universal, the pathways for implementation must consider contextual specificities. Environmental design is integral for healing, but toolkits to enable it must resonate locally. The study indicates the value of participatory methods to assess and evolve healthcare design toolkits across the Global North and South. Adapting toolkits can catalyze the spread of healing environments where they are most needed.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the process. The authors’ contributions are as follows: Conceptualization: Bedia Tekbiyik Tekin, Ozgur Dincyurek Methodology: Bedia Tekbiyik Tekin, Ozgur Dincyurek Formal analysis: Bedia Tekbiyik Tekin. Writing-original draft preparation: Bedia Tekbiyik Tekin Supervision, review, and editing: Ozgur Dincyurek. All authors have read the manuscript and they contributed to the work.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was conducted according to the guidelines of the NHS under the open government license and approved by Eastern Mediterranean University, Research, and Publication Ethics Board.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed Consent Statement was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results can be requested from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Cancer Association of North Cyprus for their cooperation in collecting data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

The appendix is attached as AEDET Toolkit QUESTIONNAIRE and ASPECT Toolkit Questionnaire distributed to the respondents.

References

- Huisman, E.; Morales, E.; van Hoof, J.; Kort, H. Healing environment: A review of the impact of physical environmental factors on users. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 58, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nightingale, F. Introductory notes on lying-in institutions. London: Longmans, Green, 1871:3.

- Tekin, B.H.; Corcoran, R.; Gutiérrez, R.U. A Systematic Review and Conceptual Framework of Biophilic Design Parameters in Clinical Environments. HERD: Heal. Environ. Res. Des. J. 2022, 16, 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MD, E. M. S. Healing Spaces: The Science of Place and Well-Being; Harvard University Press, 2010.p.50-70.

- 2016.

- Alfonsi, E.; Capolongo, S.; Buffoli, M. Evidence Based Design and healthcare: an unconventional approach to hospital design. 26, 43. [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D Kirk, Hamilton; Watkins, D. H. D Kirk Hamilton; Watkins, D. H. Evidence-Based Design for Multiple Building Types; John Wiley & Sons, Inc: Hoboken, N.J. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cama, R. Evidence-Based Healthcare Design; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, N.J, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, L.L.; Crane, J.; Deming, K.A.; Barach, P. Using Evidence to Design Cancer Care Facilities. Am. J. Med Qual. 2020, 35, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- W.D., Ryan, C.O., & Clancy, J.O. 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design. 2014.

- Kellert, S. R.; Heerwagen, J.; Mador, M. Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life; Wiley: Hoboken, N.J. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- The world health organisation. Public Heal. 1946, 60, 74–75. [CrossRef]

- Høybye, M.T. Healing environments in cancer treatment and care. Relations of space and practice in hematological cancer treatment. Acta Oncol. 2012, 52, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jencks, C. ; The Architecture of Hope; Frances Lincoln Ltd., 2015.

- 2018.

- Gashoot, M.M. Holistic Healing Framework: Impact of the Physical Surrounding Design on Patient Healing and Wellbeing. Art Des. Rev. 2022, 10, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phiri, M. Design Tools for Evidence-Based Healthcare Design; Routledge: London, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gann, D.; Salter, A.; Whyte, J. Design Quality Indicator as a tool for thinking. Build. Res. Inf. 2003, 31, 318–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R. Nature, and Mental Health: Biophilia and Biophobia. The Environment and Mental Health 2013, 179–196. [Google Scholar]

- Sussman, A.; Hollander, J. B. Cognitive Architecture: Designing for How We Respond to the Built Environment; Routledge: New York, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tasser, E.; Lavdas, A.A.; Schirpke, U. Assessing landscape aesthetic values: Do clouds in photographs influence people’s preferences? PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0288424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KKTC Sağlık Bakanlığı > İSTATİSTİKİ BİLGİLER > KANSER İSTATİSTİKLERİ. Gov.ct.tr. http://arsiv.salik.gov.ct.tr/ (accessed 2023-06-20).

- Ruggles, D. H. Beauty, Neuroscience, and Architecture: Timeless Patterns and Their Impact on Our Well-Being; Fibonacci: Denver, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, E.; Hignett, S. DEEP SCOPE: A Framework for Safe Healthcare Design. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 7780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CHD. Center for Health Design. Available online: https://www.pcpd.scot.nhs.uk/Capital/SCIM_Pilot/2017/AEDET%20Refresh%20Guidance.docx (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Ghazali, R.; Abbas, M.Y. Natural Environment in Paediatric Wards: Status and Implications. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 68, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalouch, C.; Aspinall, P.A.; Smith, H. Design Criteria for Privacy-Sensitive Healthcare Buildings. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2016, 8, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, F.J. Post-occupancy evaluation Correlated with Medical Staffs' Satisfaction: A Case Study of Indoor Environments of General Hospitals in Sulaimani City. J. Eng. 2021, 27, 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobus, R. L. Building Type Basics for Healthcare Facilities; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- CHD. Center for Health Design. Available online: https://www.healthdesign.org/certification-outreach/edac/about-ebd (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Preiser Wolfgang F., E. Harvey Z. Rabinowitz and Edward T. White. 1988. Post-Occupancy Evaluation. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

- Miller, R. L.; Swensson, E. S. New Directions In Hospital and Healthcare Facility Design; McGraw-Hill: New York, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Der. , V., D. J. M. van; van, W. H. B. R. Architecture in Use: An Introduction to the Programming, Design, Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- URL: The National Archives. The National Archives ASPECT. Available online: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130124042001/http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_082081.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Kvåle, K.; Bondevik, M. What is important for patient centred care? A qualitative study about the perceptions of patients with cancer. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2008, 22, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulrich, R.S. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 1984, 224, 420–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- URL. Available online: http://bndh.gov.ct.tr/tr/servisler/dahili-birimler/onkoloji (accessed on 8 February 2022).

- Available online: https://neareasthospital.com/departments/medical-oncology/? (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Zeisel, J. Inquiry by Design: Environment/Behavior/Neuroscience in Architecture, Interiors, Landscape, and Planning; W.W. Norton & Co.: New York, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S. How design impacts wellness. 1992, 35, 20–5.

- Berg, A. E. V. D. Health impacts of healing environments: a review of the evidence for benefits of nature, daylight, fresh air, and quiet in healthcare settings. University Hospital, Groningen, 2005.

- Greenberg, J.; Jonas, E. Psychological motives and political orientation--The left, the right, and the rigid: Comment on Jost et al. (2003). Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Changing Hospital Architecture / Edited by Sunand Prasad. London: RIBA, 2008.

- Ismaeil, E.M.H.; Sobaih, A.E.E. Enhancing Healing Environment and Sustainable Finishing Materials in Healthcare Buildings. Buildings 2022, 12, 1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. , A.M.; A., F.J.; A., A.H.; J., A.M. Theoretical Issues and Conceptual Framework for Physical Facilities Design in Hospital Buildings. J. Arch. Environ. Struct. Eng. Res. 2021, 4, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantavou, K.; Giallouros, G.; Philippopoulos, K.; Piovani, D.; Cartalis, C.; Bonovas, S.; Nikolopoulos, G.K. Thermal Conditions and Hospital Admissions: Analysis of Longitudinal Data from Cyprus (2009–2018). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 13361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).