Submitted:

04 September 2023

Posted:

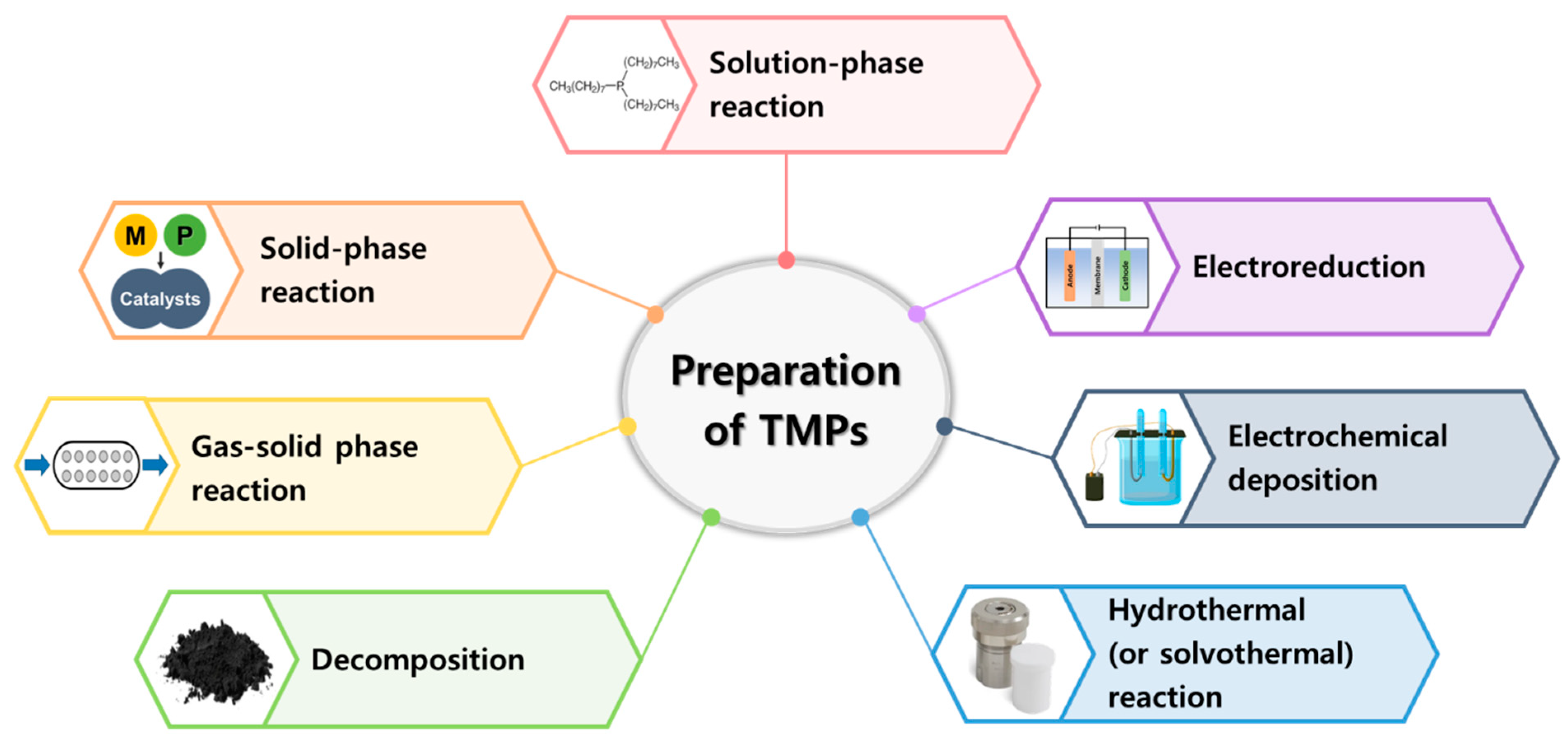

06 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

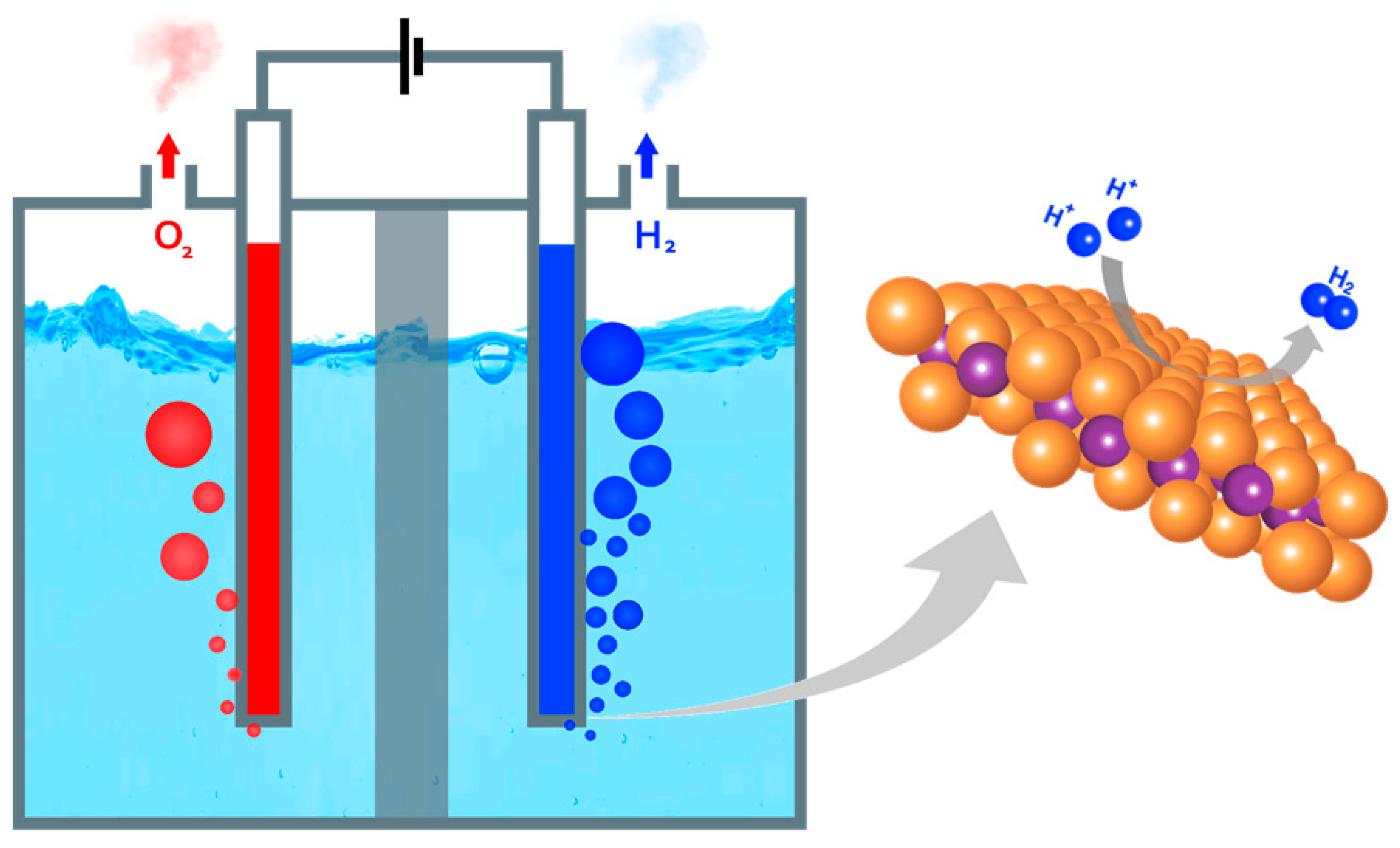

2. HER mechanism

3. Preparation of Transition-Metal Phosphides (TMPs)

3.1. Solution-phase reactions

3.2. Solid-phase reaction

3.3. Gas-solid phase reaction

3.4. Decomposition

3.5. Hydrothermal(or solvothermal) reaction

3.6. Electrochemical deposition

3.7. Electroreduction

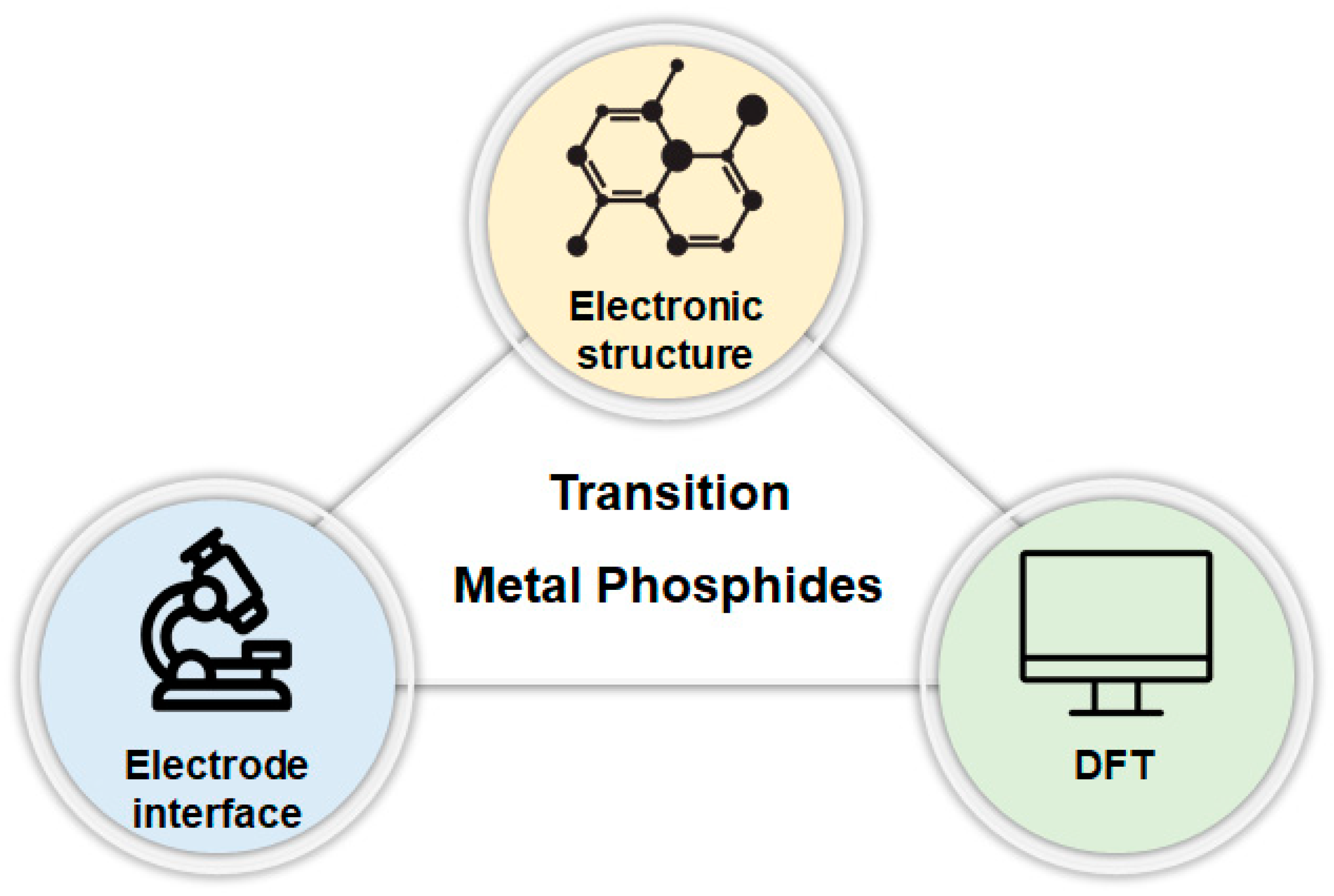

4. Electrocatalytic performance for HER in alkaline

4.1. Ni-based TMPs

4.1.1. Ni-P structure

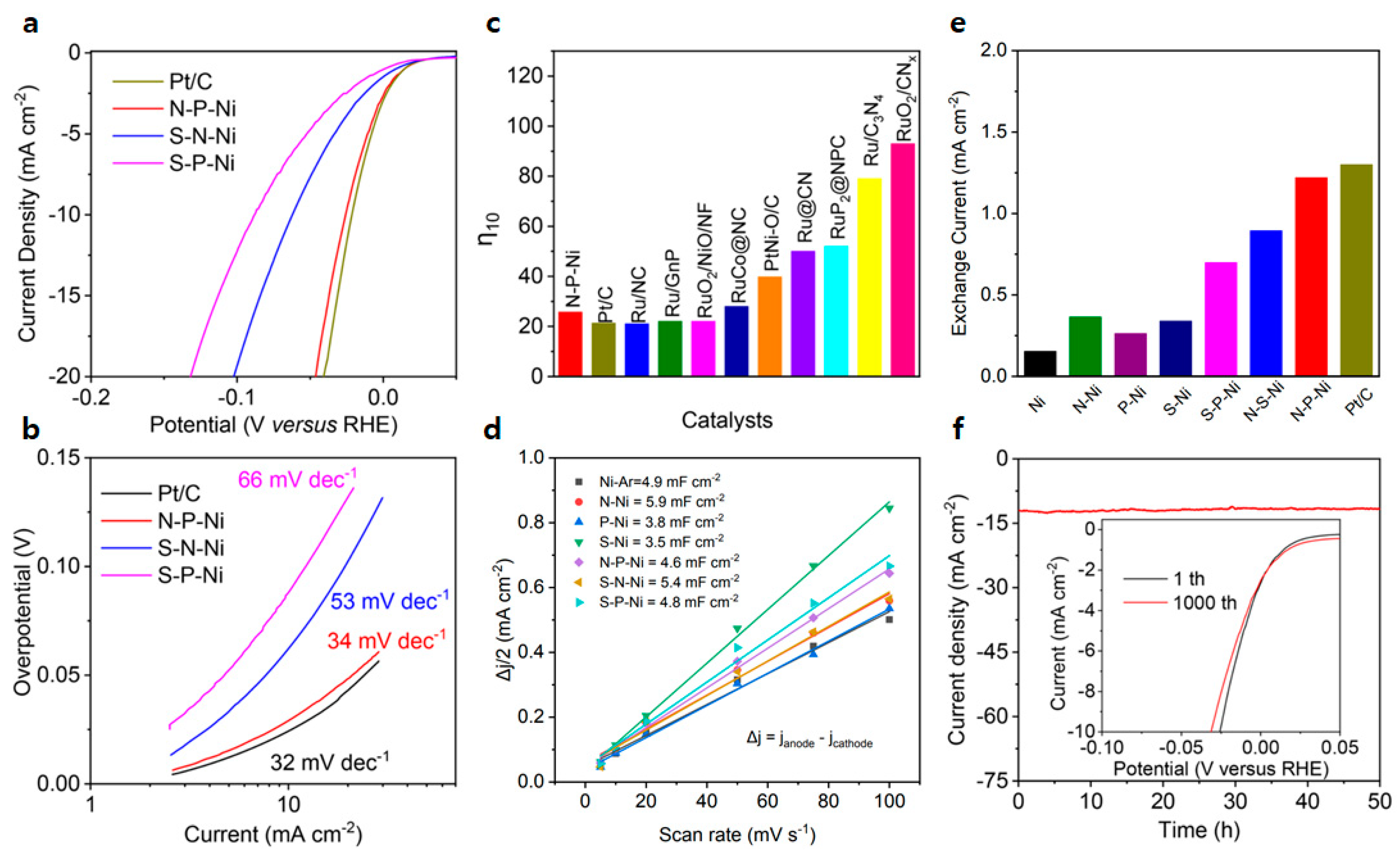

4.1.2. Ni-N&P structure

4.1.3. Ni-M-P (M: metal) structure.

4.2. Co-based TMPs

4.2.1. Co-P structure

4.2.2. Cu-Co-P structure

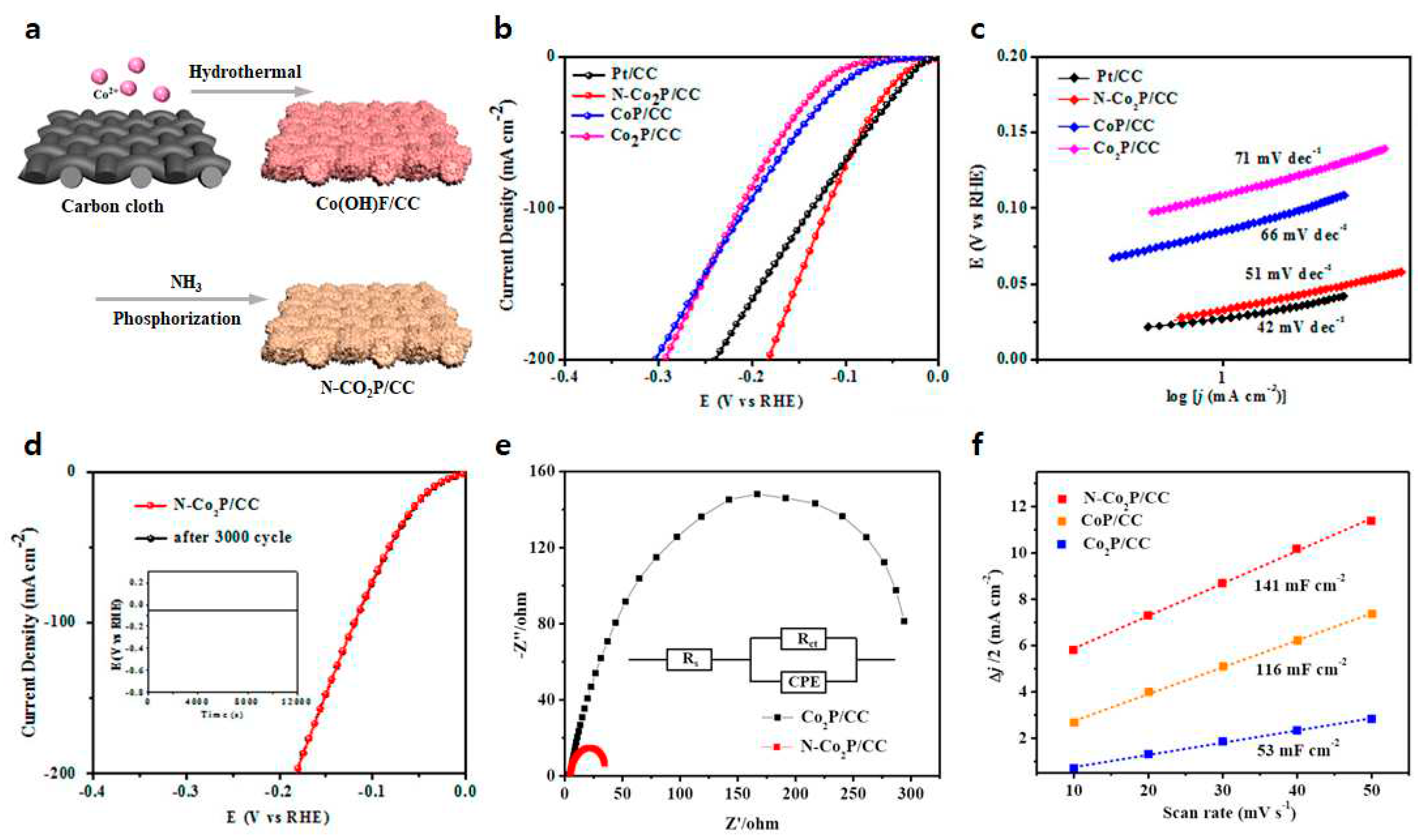

4.2.3. N-Co-P structure

4.3. Fe-based TMPs

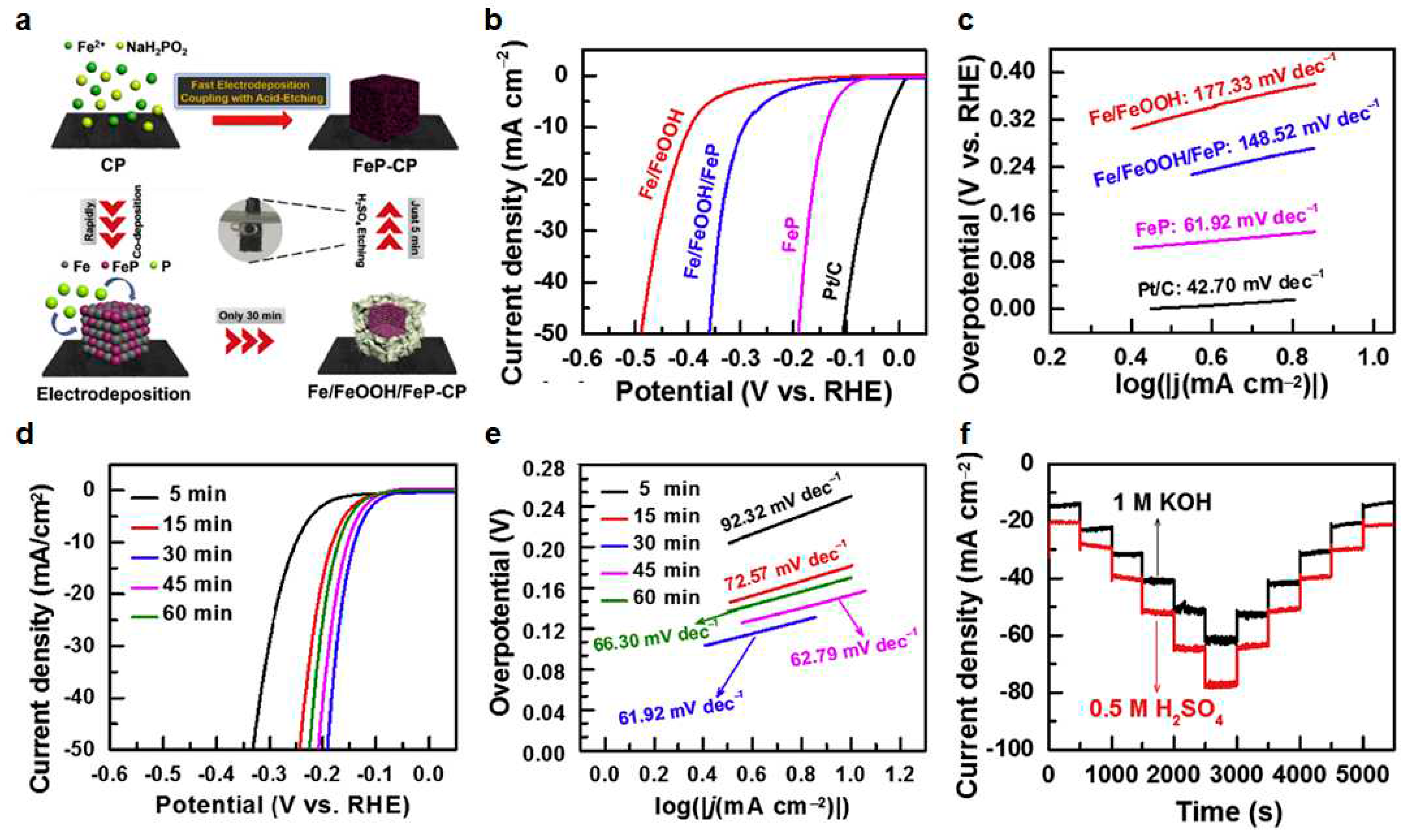

4.3.1. Fe-P structure

4.3.2. M-Fe-P (M = metal) structure

4.3.3. Fe-P/M-P (M = metal) structure

4.4. Mo-based TMPs

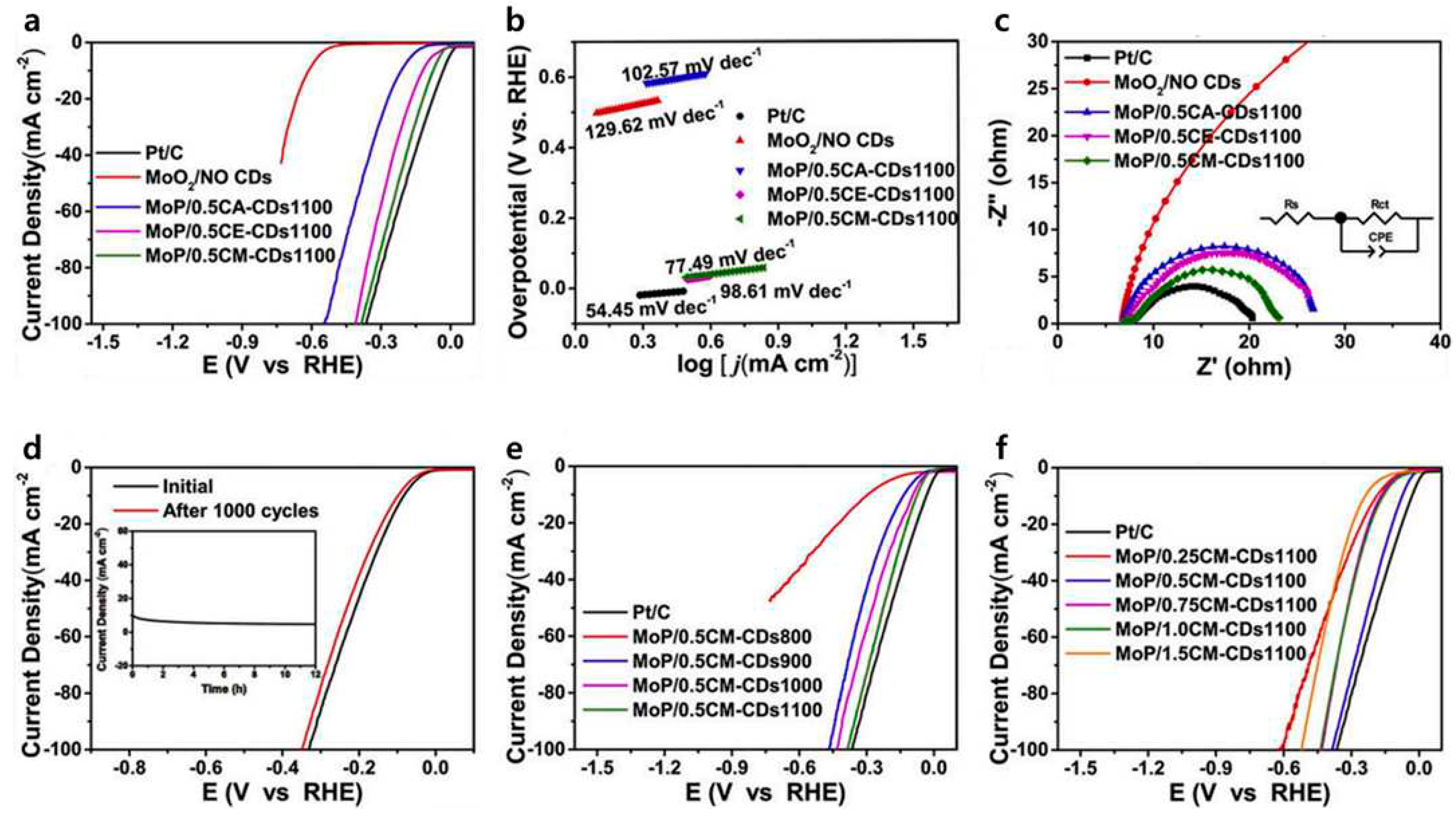

4.4.1. Mo-P structure

4.4.2. Mo-Ni-P structure.

4.4.3. Mo-P/Ni-P structure

4.5. Others

| Electrocatalyst | Overpotential (mV) at a current density of 10 mA cm−2 |

Tafel slope (mV dec−1) |

Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ni2P/Ni composite | 41 | 50 | [73] |

| Ni-FeP/TiN/CC | 75 | 73 | [96] |

| Ni/Ni2P@3DNSC | 92 | 65 | [97] |

| NiCoFe-PS nanorod/NF | 97.8 | 51.8 | [77] |

| NSP-Ni3FeN/NF | 45 | 75 | [98] |

| Ni2P/Ni0.96S/NF | 72 | 149 | [99] |

| NiCoP/CC | 62 | 68.2 | [76] |

| Ni2P/MoO2/NF HNRs | 34 | 45.8 | [100] |

| sc-Ni2Pδ-/NiHO | 60 | 75 | [101] |

| Ni2P-Ni3S2 HNAs/NF | 80 | 65 | [102] |

| NiMoP | 400 | 163 | [103] |

| NiMnP | 490 | 238 | [103] |

| NiFeP | 690 | 116 | [103] |

| NiCoP | 530 | 116 | [103] |

| Ni2P | 710 | 103 | [103] |

| N-NiCoP/NCF | 78 | 83.2 | [104] |

| v-Ni12P5 | 27.7 | 30.88 | [105] |

| Ni2P-NiP2 HNPs/NF | 59.7 | 58.8 | [106] |

| Ni2P/rGO | 142 | 58 | [74] |

| Ni-Co-P HNBs | 107 | 46 | [75] |

| Ni2P/Ni/NF | 98 | 72 | [107] |

| Ni5P4 | 47 | 56 | [108] |

| NiCo2Px NW | 58 | 34.3 | [109] |

| Ni2P-NiCoP@NCCs | 116 | 79 | [110] |

| (Ni0.33Fe0.67)2P NS | 84 | [111] | |

| NiFe LDH@NiCoP/NF | 120 | 88.2 | [112] |

| Ni(OH)2-Fe2P/TM | 76 | 105 | [113] |

| R-NiZnP/NF | 50 | 53 | [114] |

| N-P-Ni | 25.8 | 34 | [12] |

| N–NiCoP NWs/CFP | 105.1 | 59.8 | [115] |

| Co-P | 94 | 42 | [116] |

| CoP/CC | 209 | 129 | [29] |

| CoP/Co2P@NC | 198 | 82 | [78] |

| CoP@BCN | 215 | [79] | |

| O, Cu-CoP-2 | 74 | 57.7 | [80] |

| S-CoP@NF | 109 | 79 | [117] |

| Zn0.075,S-Co0.925P NRCs/CP | 37 | 41.5 | [118] |

| CoFeP | 177 | 72 | [119] |

| Co3S4/MoS2/Ni2P | 178 | 98 | [120] |

| Zn0.08Co0.92P/TM | 67 | [121] | |

| Al-CoP/CC | 38 | 45 | [122] |

| Al-CoP/NF | 66 | 94 | [123] |

| N-Co2P/CC | 34 | 51 | [81] |

| C- (Fe-Ni)P@PC/(Ni-Co)P@CC | 142 | 98 | [124] |

| CoP-CeO2/Ti | 43 | 45 | [125] |

| FeP (NPC FeP/CP) | 140 | 61.92 | [72] |

| FeP NAs/CC | 218 | 146 | [126] |

| meso-FeP/CC | 84 | 60 | [82] |

| FeP-CoMoP | 33 | 51 | [87] |

| NFP/C | 95 | 72 | [83] |

| MoO2-FeP@C | 103 | 48 | [84] |

| MoP/CNT | 86 | 73 | [88] |

| MoP2 NS/CC | 67 | 70 | [127] |

| MoP-RGO | 152 | 69 | [89] |

| MoP/MWCNTs | 155 | 56.8 | [128] |

| Mo-Ni2P NWs/NF | 78 | 109 | [92] |

| MoP/Ni2P/NF | 75 | 100.2 | [93] |

| MoP/CDs | 70 | 77.49 | [91] |

| C-WP/W | 133 | 70.1 | [129] |

| Cu3P/CF | 222 | 148 | [95] |

| WP NAs/CC | 150 | 102 | [94] |

5. Future Plan

6. Conclusion

Acknowledgements

References

- Xu, S.; Zhao, H.; Li, T.; Liang, J.; Lu, S.; Chen, G.; Gao, S.; Asiri, A.M.; Wu, Q.; Sun, X. Iron-based phosphides as electrocatalysts for the hydrogen evolution reaction: recent advances and future prospects. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 19729–19745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balderas-Xicohténcatl, R.; Schmieder, P.; Denysenko, D.; Volkmer, D.; Hirscher, M. High Volumetric Hydrogen Storage Capacity using Interpenetrated Metal–Organic Frameworks. Energy Technol. 2018, 6, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Qiao, S.Z. Engineering of Carbon-Based Electrocatalysts for Emerging Energy Conversion: From Fundamentality to Functionality. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 5372–5378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Liu, D.; Li, H.; Li, J. Molybdenum Carbide-Decorated Metallic Cobalt@Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Polyhedrons for Enhanced Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. Small 2018, 14, 1704227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, H.; Joo, J.; Chaudhari, N.K.; Choi, S.-I.; Lee, K. Recent Progress in Bifunctional Electrocatalysts for Overall Water Splitting under Acidic Conditions. ChemElectroChem 2019, 6, 3244–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, B.; Chen, L.; Shi, J. Anion-Containing Noble-Metal-Free Bifunctional Electrocatalysts for Overall Water Splitting. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 3688–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Li, G.; Han, Z.; Wang, Z.; Huang, X.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, J.; He, C. Recent progress in the hybrids of transition metals/carbon for electrochemical water splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 14380–14390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhu, Y.-P.; Yuan, Z.-Y. Three-Dimensional Electrocatalysts for Sustainable Water Splitting Reactions. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 2016, 1916–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, H.B. Powering the planet with solar fuel. Nat. Chem. 2009, 1, 7–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millet, P.; Andolfatto, F.; Durand, R. Design and performance of a solid polymer electrolyte water electrolyzer. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 1996, 21, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.-Y.; Mahmood, J.; Jeon, I.-Y.; Baek, J.-B. Recent advances in ruthenium-based electrocatalysts for the hydrogen evolution reaction. Nanoscale Horiz. 2020, 5, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Liu, X.; Chen, S.; Vasileff, A.; Li, L.; Jiao, Y.; Song, L.; Zheng, Y.; Qiao, S.-Z. Heteroatom-Doped Transition Metal Electrocatalysts for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. ACS Energy Lett. 2019, 4, 805–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, N.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, J.-W.; Pan, L.; Zhang, X.; Zou, J.-J. Electrocatalysts for Hydrogen Evolution in Alkaline Electrolytes: Mechanisms, Challenges, and Prospective Solutions. Adv. Sci. 2018, 5, 1700464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, S.A.; Iqbal, M.I.; Kim, S.-H.; Jung, K.-D. Catalytic Activity of Urchin-like Ni nanoparticles Prepared by Solvothermal Method for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction in Alkaline Solution. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 227, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalbino, F.; Delsante, S.; Borzone, G.; Angelini, E. Electrocatalytic behaviour of Co–Ni–R (R=Rare earth metal) crystalline alloys as electrode materials for hydrogen evolution reaction in alkaline medium. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2008, 33, 6696–6703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalbino, F.; Macciò, D.; Saccone, A.; Angelini, E.; Delfino, S. Fe–Mo–R (R = rare earth metal) crystalline alloys as a cathode material for hydrogen evolution reaction in alkaline solution. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2011, 36, 1965–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Cao, J.; Dong, J.; Du, H.; Zhang, H.; Chen, J.; Xu, L. Ordered mesoporous Ni-Co alloys for highly efficient electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2017, 42, 6637–6645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Gan, L.; Wang, J.; Yang, X. Experimental and theoretical insights into sustained water splitting with an electrodeposited nanoporous nickel hydroxide@nickel film as an electrocatalyst. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 7744–7748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xia, G.; Zhang, R.; Jiang, P.; Chen, J.; Chen, Q. MOF-derived RuO2/Co3O4 heterojunctions as highly efficient bifunctional electrocatalysts for HER and OER in alkaline solutions. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 3686–3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Zhang, L.; Gao, G.; Chen, H.; Wang, B.; Zhou, J.; Soo, M.T.; Hong, M.; Yan, X.; Qian, G.; et al. A Heterostructure Coupling of Exfoliated Ni–Fe Hydroxide Nanosheet and Defective Graphene as a Bifunctional Electrocatalyst for Overall Water Splitting. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1700017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruqia, B.; Choi, S.-I. Pt and Pt–Ni(OH)2 Electrodes for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction in Alkaline Electrolytes and Their Nanoscaled Electrocatalysts. ChemSusChem 2018, 11, 2643–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, E.; Sun, G. Layered transition-metal hydroxides for alkaline hydrogen evolution reaction. Chinese J. Catal. 2020, 41, 574–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.H. Evaluation of electrocatalysts for water electrolysis in alkaline solutions. J. electroanal. chem. interfacial electrochem. 1975, 60, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, J.H.; Conway, B.E. Structural specificity of the kinetics of the hydrogen evolution reaction on the low-index surfaces of Pt single-crystal electrodes in 0.5 M dm−3 NaOH. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1999, 461, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilovic, N.; Subbaraman, R.; Strmcnik, D.; Stamenkovic, V.; Markovic, N. Electrocatalysis of the HER in acid and alkaline media. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2013, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, K.; Zhang, D. Recent progress in alkaline water electrolysis for hydrogen production and applications. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2010, 36, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, G.; Henne, R.; Mohr, P.; Peinecke, V. High performance electrodes for an advanced intermittently operated 10-kW alkaline water electrolyzer. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 1998, 23, 761–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhang, B. Recent advances in transition metal phosphide nanomaterials: synthesis and applications in hydrogen evolution reaction. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 1529–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Liu, Q.; Asiri, A.M.; Sun, X. Self-Supported Nanoporous Cobalt Phosphide Nanowire Arrays: An Efficient 3D Hydrogen-Evolving Cathode over the Wide Range of pH 0–14. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 7587–7590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Liu, Q.; Liang, Y.; Tian, J.; Asiri, A.M.; Sun, X. A Cost-Effective 3D Hydrogen Evolution Cathode with High Catalytic Activity: FeP Nanowire Array as the Active Phase. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 12855–12859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Dong, P.; Craig, S.R.; Ajayan, P.M.; Ye, M.; Shen, J. Transforming Nickel Hydroxide into 3D Prussian Blue Analogue Array to Obtain Ni2P/Fe2P for Efficient Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1800484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, Q.; Jing, F.; Chi, K.; Wang, S. Large-scale printing synthesis of transition metal phosphides encapsulated in N, P co-doped carbon as highly efficient hydrogen evolution cathodes. Nano Energy 2018, 51, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, P.; Chen, W.; Wang, X. A Review of Phosphide-Based Materials for Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. Adv. Energy Mater. 2015, 5, 1500985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yan, M.; Zhou, X.; Huang, Z.-Q.; Xia, Z.; Chang, C.-R.; Ma, Y.; Qu, Y. Mechanistic Insights on Ternary Ni2−xCoxP for Hydrogen Evolution and Their Hybrids with Graphene as Highly Efficient and Robust Catalysts for Overall Water Splitting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 6785–6796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Zhu, S.; Chen, S.; Li, Y.; Ma, L.; Wu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, C.; Yang, X.; et al. Amorphous Metallic NiFeP: A Conductive Bulk Material Achieving High Activity for Oxygen Evolution Reaction in Both Alkaline and Acidic Media. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1606570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Shen, Z.; Zhu, C.; Li, J.; Ding, Z.; Wang, P.; Pan, F.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, H.; Wang, S.; et al. Nitrogen-Doped CoP Electrocatalysts for Coupled Hydrogen Evolution and Sulfur Generation with Low Energy Consumption. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1800140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshahawy, A.M.; Guan, C.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Hu, Y.; Wu, H.; Pennycook, S.J.; Wang, J. Sulfur-doped cobalt phosphide nanotube arrays for highly stable hybrid supercapacitor. Nano Energy 2017, 39, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Kim, T.; Lee, K.; Li, J. Recent Advances in Transition Metal Phosphide Electrocatalysts for Water Splitting under Neutral pH Conditions. ChemElectroChem 2020, 7, 3578–3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, P.E.R.; Grosvenor, A.P.; Cavell, R.G.; Mar, A. X-ray Photoelectron and Absorption Spectroscopy of Metal-Rich Phosphides M2P and M3P (M = Cr−Ni). Chem. Mater. 2008, 20, 7081–7088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callejas, J.F.; Read, C.G.; Roske, C.W.; Lewis, N.S.; Schaak, R.E. Synthesis, Characterization, and Properties of Metal Phosphide Catalysts for the Hydrogen-Evolution Reaction. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 6017–6044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, H.; Huang, H.; Jiao, H.; Du, Y. MOF-derived porous Ni2P nanosheets as novel bifunctional electrocatalysts for the hydrogen and oxygen evolution reactions. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 18720–18727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Tian, J.; Cui, W.; Jiang, P.; Cheng, N.; Asiri, A.M.; Sun, X. Carbon Nanotubes Decorated with CoP Nanocrystals: A Highly Active Non-Noble-Metal Nanohybrid Electrocatalyst for Hydrogen Evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 6710–6714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Rodriguez, J.A. Catalysts for Hydrogen Evolution from the [NiFe] Hydrogenase to the Ni2P(001) Surface: The Importance of Ensemble Effect. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 14871–14878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popczun, E.J.; McKone, J.R.; Read, C.G.; Biacchi, A.J.; Wiltrout, A.M.; Lewis, N.S.; Schaak, R.E. Nanostructured Nickel Phosphide as an Electrocatalyst for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 9267–9270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, J.; Liu, Q.; Cheng, N.; Asiri, A.M.; Sun, X. Self-Supported Cu3P Nanowire Arrays as an Integrated High-Performance Three-Dimensional Cathode for Generating Hydrogen from Water. Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 9731–9735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.-C.; Cao, S.; Fu, W.-F.; Chen, Y. Ultrafine CoP Nanoparticles Supported on Carbon Nanotubes as Highly Active Electrocatalyst for Both Oxygen and Hydrogen Evolution in Basic Media. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 28412–28419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Zhou, Y.-X.; Jiang, H.-L. Metal–organic framework-based CoP/reduced graphene oxide: high-performance bifunctional electrocatalyst for overall water splitting. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 1690–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; You, B.; Sheng, M.; Sun, Y. Electrodeposited Cobalt-Phosphorous-Derived Films as Competent Bifunctional Catalysts for Overall Water Splitting. Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 6349–6352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greeley, J.; Jaramillo, T.F.; Bonde, J.; Chorkendorff, I.; Nørskov, J.K. Computational high-throughput screening of electrocatalytic materials for hydrogen evolution. Nat. Mater. 2006, 5, 909–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Qu, J.; Li, J. Highly Active and Stable Catalysts of Phytic Acid-Derivative Transition Metal Phosphides for Full Water Splitting. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 14686–14693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.; Fu, B.; Zhao, J.; Li, X.; Ma, B.; Chen, Y. A review of the electrocatalysts on hydrogen evolution reaction with an emphasis on Fe, Co and Ni-based phosphides. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 55, 14081–14104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Ling, T.; Chen, S.; Jin, B.; Vasileff, A.; Jiao, Y.; Song, L.; Luo, J.; Qiao, S.-Z. Non-metal Single-Iodine-Atom Electrocatalysts for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 12252–12257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, M.; Wang, D.-Y.; Chen, C.-C.; Hwang, B.-J.; Dai, H. A mini review on nickel-based electrocatalysts for alkaline hydrogen evolution reaction. Nano Res. 2016, 9, 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhou, M.; Long, A.; Xue, Y.; Liao, H.; Wei, C.; Xu, Z.J. Heterostructured Electrocatalysts for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction Under Alkaline Conditions. Nanomicro Lett 2018, 10, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Jaroniec, M.; Qiao, S.Z. Design of electrocatalysts for oxygen- and hydrogen-involving energy conversion reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 2060–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theerthagiri, J.; Murthy, A.P.; Lee, S.J.; Karuppasamy, K.; Arumugam, S.R.; Yu, Y.; Hanafiah, M.M.; Kim, H.-S.; Mittal, V.; Choi, M.Y. Recent progress on synthetic strategies and applications of transition metal phosphides in energy storage and conversion. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 4404–4425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, S.C.; Fodor, P.S.; Tsoi, G.M.; Wenger, L.E.; Brock, S.L. Application of De-silylation Strategies to the Preparation of Transition Metal Pnictide Nanocrystals: The Case of FeP. Chem. Mater. 2003, 15, 4034–4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, Z. Selective Synthesis of Magnetic Fe2P/C and FeP/C Core/Shell Nanocables. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthuswamy, E.; Brock, S.L. Oxidation Does Not (Always) Kill Reactivity of Transition Metals: Solution-Phase Conversion of Nanoscale Transition Metal Oxides to Phosphides and Sulfides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 15849–15851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, C.-C.; Ren, J.-T.; Yuan, Z.-Y. Transition Metal Phosphide-Based Materials for Efficient Electrochemical Hydrogen Evolution: A Critical Review. ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 3357–3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Li, Y. Recent advances in heterogeneous electrocatalysts for the hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 14942–14962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, B.F.; Walmsley, R.H. Magnetic Susceptibility and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance in Transition-Metal Monophosphides. Phys. Rev. 1966, 148, 933–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Zhou, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, C.; Chen, Y. Synthesis and application of transition metal phosphides as electrocatalyst for water splitting. Sci. Bull. 2017, 62, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Kolen'ko, Y.V.; Bao, X.Q.; Kovnir, K.; Liu, L. One-Step Synthesis of Self-Supported Nickel Phosphide Nanosheet Array Cathodes for Efficient Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Generation. Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 8306–8310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledendecker, M.; Krick Calderón, S.; Papp, C.; Steinrück, H.-P.; Antonietti, M.; Shalom, M. The Synthesis of Nanostructured Ni5P4 Films and their Use as a Non-Noble Bifunctional Electrocatalyst for Full Water Splitting. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 12361–12365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, B.; Chen, Y. Iron phosphides supported on three-dimensional iron foam as an efficient electrocatalyst for water splitting reactions. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 54, 14872–14883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.P.; Bae, E.J.; Yu, J.-S. Fe–P: A New Class of Electroactive Catalyst for Oxygen Reduction Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 3165–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Z.; Amiinu, I.S.; Zhang, C.; Wang, M.; Kou, Z.; Mu, S. Phytic acid-derivative transition metal phosphides encapsulated in N,P-codoped carbon: an efficient and durable hydrogen evolution electrocatalyst in a wide pH range. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 3555–3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrappa, K.; Adschiri, T. Hydrothermal technology for nanotechnology. Prog. Cryst. Growth Charact. Mater. 2007, 53, 117–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.H.; Cheung, C.K.; Leung, Y.H.; Djurišić, A.B.; Ling, C.C.; Beling, C.D.; Fung, S.; Kwok, W.M.; Chan, W.K.; Phillips, D.L.; et al. Defects in ZnO Nanorods Prepared by a Hydrothermal Method. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 20865–20871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Fu, W.; Yang, X.; Huang, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y. Recent advancements in heterostructured interface engineering for hydrogen evolution reaction electrocatalysis. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 6926–6956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Qiu, F.; Yuan, W.; Guo, M.; Yuan, C.; Lu, Z.-H. Novel electrocatalyst of nanoporous FeP cubes prepared by fast electrodeposition coupling with acid-etching for efficient hydrogen evolution. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 329, 135185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhuo, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, B. Ni2P Nanosheets/Ni Foam Composite Electrode for Long-Lived and pH-Tolerable Electrochemical Hydrogen Generation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 2376–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, L.; Jiang, H.; Xing, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, D.; Gu, X.; Dai, P.; Li, L.; Zhao, X. Nickel metal–organic framework implanted on graphene and incubated to be ultrasmall nickel phosphide nanocrystals acts as a highly efficient water splitting electrocatalyst. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 1682–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, E.; Feng, Y.; Nai, J.; Zhao, D.; Hu, Y.; Lou, X.W. Construction of hierarchical Ni–Co–P hollow nanobricks with oriented nanosheets for efficient overall water splitting. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 872–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Yang, L.; Yang, F.; Cheng, G.; Luo, W. Nest-like NiCoP for Highly Efficient Overall Water Splitting. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 4131–4137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Hu, H.; Sun, B.; Wang, N.; Hu, W.; Komarneni, S. Self-Supportive Mesoporous Ni/Co/Fe Phosphosulfide Nanorods Derived from Novel Hydrothermal Electrodeposition as a Highly Efficient Electrocatalyst for Overall Water Splitting. Small 2019, 15, 1905201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Ren, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, Z.-Y. Well-Defined Phase-Controlled Cobalt Phosphide Nanoparticles Encapsulated in Nitrogen-Doped Graphitized Carbon Shell with Enhanced Electrocatalytic Activity for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction at All-pH. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 8993–9001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, H.; Guo, W.; Meng, W.; Mahmood, A.; Zhao, R.; Wang, Q.; Zou, R. Metal–Organic Frameworks Derived Cobalt Phosphide Architecture Encapsulated into B/N Co-Doped Graphene Nanotubes for All pH Value Electrochemical Hydrogen Evolution. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1601671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Sun, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, G.; Zhang, Q.; Gu, L.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Fan, H.J. Yin-Yang Harmony: Metal and Nonmetal Dual-Doping Boosts Electrocatalytic Activity for Alkaline Hydrogen Evolution. ACS Energy Lett. 2018, 3, 2750–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, Y.; Li, P.; Zhou, J.; Cheng, G.; Chen, S.; Luo, W. Tailoring the Electronic Structure of Co2P by N Doping for Boosting Hydrogen Evolution Reaction at All pH Values. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 3744–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Z.; Yuan, S.; Yang, G.; Wang, K.; Li, X.; Li, N.; Jing, S. Self-Supported Mesoporous Iron Phosphide with High Active-Site Density for Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution in Acidic and Alkaline Media. ChemElectroChem 2020, 7, 4943–4948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.F.; Yu, L.; Lou, X.W. Highly crystalline Ni-doped FeP/carbon hollow nanorods as all-pH efficient and durable hydrogen evolving electrocatalysts. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaav6009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Jiao, Y.; Yan, H.; Xie, Y.; Wu, A.; Dong, X.; Guo, D.; Tian, C.; Fu, H. Interfacial Engineering of MoO2-FeP Heterojunction for Highly Efficient Hydrogen Evolution Coupled with Biomass Electrooxidation. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2000455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Wu, A.; Yan, H.; Xiao, Y.; Tian, C.; Fu, H. Trapping [PMo12O40] 3− clusters into pre-synthesized ZIF-67 toward MoxCoxC particles confined in uniform carbon polyhedrons for efficient overall water splitting. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 4746–4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-S.; Tang, Y.-J.; Liu, C.-H.; Li, S.-L.; Li, R.-H.; Dong, L.-Z.; Dai, Z.-H.; Bao, J.-C.; Lan, Y.-Q. Polyoxometalate-based metal–organic framework-derived hybrid electrocatalysts for highly efficient hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 1202–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Li, F.; Xu, L.; Wang, X.; Jiao, H.; Chen, Y. Self-Supported FeP-CoMoP Hierarchical Nanostructures for Efficient Hydrogen Evolution. Chem. Asian. J. 2020, 15, 1590–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, F.; Liang, Y.; Wang, R. Molybdenum Phosphide/Carbon Nanotube Hybrids as pH-Universal Electrocatalysts for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1706523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Song, M.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, X. Various strategies to tune the electrocatalytic performance of molybdenum phosphide supported on reduced graphene oxide for hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 536, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xia, H.; Peng, Z.; Lv, C.; Jin, L.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, C. Graphene Porous Foam Loaded with Molybdenum Carbide Nanoparticulate Electrocatalyst for Effective Hydrogen Generation. ChemSusChem 2016, 9, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Li, Y.; Shang, L.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, T.; Lu, S. Designed controllable nitrogen-doped carbon-dots-loaded MoP nanoparticles for boosting hydrogen evolution reaction in alkaline medium. Nano Energy 2020, 72, 104730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Hang, L.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, T.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Lyu, X.; Li, Y. Mo doped Ni2P nanowire arrays: an efficient electrocatalyst for the hydrogen evolution reaction with enhanced activity at all pH values. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 16674–16679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, C.; Shang, M.; Mao, J.; Song, W. Hierarchical MoP/Ni2P heterostructures on nickel foam for efficient water splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 15940–15949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Asiri, A.M.; Sun, X. Tungsten Phosphide Nanorod Arrays Directly Grown on Carbon Cloth: A Highly Efficient and Stable Hydrogen Evolution Cathode at All pH Values. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 21874–21879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, C.-C.; Chen, Q.-Q.; Wang, C.-J.; Liang, F.; Lin, Z.; Fu, W.-F.; Chen, Y. Self-Supported Cedarlike Semimetallic Cu3P Nanoarrays as a 3D High-Performance Janus Electrode for Both Oxygen and Hydrogen Evolution under Basic Conditions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 23037–23048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Qasim, A.M.; Jin, W.; Wang, L.; Hu, L.; Miao, Y.; Li, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Huo, K.; et al. Ni-doped amorphous iron phosphide nanoparticles on TiN nanowire arrays: An advanced alkaline hydrogen evolution electrocatalyst. Nano Energy 2018, 53, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, T.; Li, X.; Bai, Y.; Lyu, X.; Liu, G.; Cai, W.; Li, Y. Bifunctional Hybrid Ni/Ni2P Nanoparticles Encapsulated by Graphitic Carbon Supported with N, S Modified 3D Carbon Framework for Highly Efficient Overall Water Splitting. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 5, 1800473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, C.; Liu, D.; Huang, X.; Huo, J.; Wang, S. Nanoparticle-Stacked Porous Nickel–Iron Nitride Nanosheet: A Highly Efficient Bifunctional Electrocatalyst for Overall Water Splitting. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 18652–18657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Feng, C.; Liao, T.; Hu, S.; Wu, H.; Sun, Z. Low-Cost Ni2P/Ni0.96S Heterostructured Bifunctional Electrocatalyst toward Highly Efficient Overall Urea-Water Electrolysis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 2225–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Jiang, Y.; Qu, M.; Qin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shen, W.; He, R.; Su, W.; Li, M. Strong electronic couple engineering of transition metal phosphides-oxides heterostructures as multifunctional electrocatalyst for hydrogen production. Appl. Catal. B 2020, 269, 118803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, B.; Zhang, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Davey, K.; Qiao, S.Z. Negative Charging of Transition-Metal Phosphides via Strong Electronic Coupling for Destabilization of Alkaline Water. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 11796–11800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Sun, K.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Pan, Y.; Liu, Z.; Cao, D.; Song, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, C. Three-dimensional-networked Ni2P/Ni3S2 heteronanoflake arrays for highly enhanced electrochemical overall-water-splitting activity. Nano Energy 2018, 51, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, H.-W.; Tsang, C.-S.; Li, M.M.-J.; Mo, J.; Huang, B.; Lee, L.Y.S.; Leung, Y.-c.; Wong, K.-Y.; Tsang, S.C.E. Transition metal-doped nickel phosphide nanoparticles as electro- and photocatalysts for hydrogen generation reactions. Appl. Catal. B 2019, 242, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Huang, J.; Chen, G.; Chen, W.; Song, C.; Li, C.; Ostrikov, K. In situ engineering bi-metallic phospho-nitride bi-functional electrocatalysts for overall water splitting. Appl. Catal. B 2019, 254, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Chen, S.; Ortíz-Ledón, C.A.; Jaroniec, M.; Qiao, S.-Z. Phosphorus Vacancies that Boost Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution by Two Orders of Magnitude. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 8181–8186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Li, A.; Wang, C.; Zhou, W.; Liu, S.; Guo, L. Interfacial Electron Transfer of Ni2P–NiP2 Polymorphs Inducing Enhanced Electrochemical Properties. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1803590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, B.; Jiang, N.; Sheng, M.; Bhushan, M.W.; Sun, Y. Hierarchically Porous Urchin-Like Ni2P Superstructures Supported on Nickel Foam as Efficient Bifunctional Electrocatalysts for Overall Water Splitting. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 714–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xie, Y.; Cao, H.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Xu, Z.; Wang, X.; Xiong, N.; Pan, K. Flower-Like Nickel Phosphide Microballs Assembled by Nanoplates with Exposed High-Energy (0 0 1) Facets: Efficient Electrocatalyst for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. ChemSusChem 2017, 10, 4899–4908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, X.; Yu, S.; Wen, T.; Zhu, X.; Yang, F.; Sun, X.; Wang, X.; Hu, W. Ternary NiCo2Px Nanowires as pH-Universal Electrocatalysts for Highly Efficient Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1605502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Yu, T.; Lei, W.; Liu, W.; Feng, K.; Ding, Y.; Jiang, G.; Xu, P.; Chen, Z. Nitrogen-doped carbon nanocones encapsulating with nickel–cobalt mixed phosphides for enhanced hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 16568–16572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, Q.; He, P.; Sun, X. 3D Self-Supported Fe-Doped Ni2P Nanosheet Arrays as Bifunctional Catalysts for Overall Water Splitting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1702513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Hähnel, A.; Naumann, V.; Lin, C.; Azimi, S.; Schweizer, S.L.; Maijenburg, A.W.; Wehrspohn, R.B. Bifunctional Heterostructure Assembly of NiFe LDH Nanosheets on NiCoP Nanowires for Highly Efficient and Stable Overall Water Splitting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1706847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, S.; Xia, L.; Si, C.; Qu, F.; Qu, F. Ni(OH)2–Fe2P hybrid nanoarray for alkaline hydrogen evolution reaction with superior activity. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 1201–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, S.; Chen, Y.; He, W.; Ze, T.; Chen, B. Preparation of rimose NiZnP electrode for hydrogen evolution reaction in alkaline medium by electroless and H2SO4 etching. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 719, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Qi, Y.; Sun, L.; Chen, G.; Wang, L.; Zhang, M.; Zeng, D.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Xu, K.; et al. Facile route of nitrogen doping in nickel cobalt phosphide for highly efficient hydrogen evolution in both acid and alkaline electrolytes. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 512, 145715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; You, B.; Sheng, M.; Sun, Y. Electrodeposited Cobalt-Phosphorous-Derived Films as Competent Bifunctional Catalysts for Overall Water Splitting. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 6251–6254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjum, M.A.R.; Okyay, M.S.; Kim, M.; Lee, M.H.; Park, N.; Lee, J.S. Bifunctional sulfur-doped cobalt phosphide electrocatalyst outperforms all-noble-metal electrocatalysts in alkaline electrolyzer for overall water splitting. Nano Energy 2018, 53, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y. Callistemon-like Zn and S codoped CoP nanorod clusters as highly efficient electrocatalysts for neutral-pH overall water splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 22453–22462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Qu, H.; Liu, Y.; Han, Y.; Wang, L.; Dong, B. Bimetallic CoFeP hollow microspheres as highly efficient bifunctional electrocatalysts for overall water splitting in alkaline media. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 465, 816–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, L. Hierarchical CoS/MoS2 and Co3S4/MoS2/Ni2P nanotubes for efficient electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution in alkaline media. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 25410–25419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Liu, D.; Qu, F.; Wang, D.; Zhang, L.; Ge, R.; Hao, S.; Ma, Y.; Du, G.; Asiri, A.M.; et al. Enhanced Electrocatalysis for Energy-Efficient Hydrogen Production over CoP Catalyst with Nonelectroactive Zn as a Promoter. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1700020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Tang, C.; Kong, R.; Du, G.; Asiri, A.M.; Chen, L.; Sun, X. Al-Doped CoP nanoarray: a durable water-splitting electrocatalyst with superhigh activity. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 4793–4800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, X.; Hu, Z.; Ren, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, Z.-Y. Self-supported Al-doped cobalt phosphide nanosheets grown on three-dimensional Ni foam for highly efficient water reduction and oxidation. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2019, 6, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.-N.; Zhang, L.; Huang, X.-H.; Zhu, Y.-X.; Zhang, X.; Hu, J.-S.; Lu, S.-Y. Double functionalization of N-doped carbon carved hollow nanocubes with mixed metal phosphides as efficient bifunctional catalysts for electrochemical overall water splitting. Nano Energy 2019, 65, 103995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Ren, X.; Hao, S.; Ge, R.; Liu, Z.; Asiri, A.M.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, X. Selective phosphidation: an effective strategy toward CoP/CeO2 interface engineering for superior alkaline hydrogen evolution electrocatalysis. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 1985–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Asiri, A.M.; Sun, X.; Luo, Y. Self-Supported FeP Nanorod Arrays: A Cost-Effective 3D Hydrogen Evolution Cathode with High Catalytic Activity. ACS Catal. 2014, 4, 4065–4069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Tang, C.; Liu, D.; Wang, J.; Asiri, A.M.; Sun, X. A self-standing nanoporous MoP2 nanosheet array: an advanced pH-universal catalytic electrode for the hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 7169–7173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Li, X.; Fu, C.; Zhao, X.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, J. Morphology and distribution of in-situ grown MoP nanoparticles on carbon nanotubes to enhance hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 877, 160214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Pu, Z.; Tu, Z.; Amiinu, I.S.; Liu, S.; Wang, P.; Mu, S. Integrated design and construction of WP/W nanorod array electrodes toward efficient hydrogen evolution reaction. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 327, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Feng, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Wilkinson, D.P. Non-noble Metal Electrocatalysts for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction in Water Electrolysis. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2021, 4, 473–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Carlton, C.; Risch, M.; Surendranath, Y.; Chen, S.; Furutsuki, S.; Yamada, A.; Nocera, D.G.; Shao-Horn, Y. The Nature of Lithium Battery Materials under Oxygen Evolution Reaction Conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 16959–16962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Vasileff, A.; Qiao, S.-Z. The Hydrogen Evolution Reaction in Alkaline Solution: From Theory, Single Crystal Models, to Practical Electrocatalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 7568–7579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Electrolyte | Reaction pathway | Equation |

|---|---|---|

| Alkaline electrolyte | Volmer | 2H2O + 2e− → H2 + 2OH− |

| H2O + e− → Hads + OH− | ||

| Heyrovsky | ||

| Hads + H2O + e− → H2 + OH− | ||

| Tafel | ||

| Hads + Hads → H2 (g) | ||

| Acidic electrolyte | Volmer | 2H+ + 2e− → H2 |

| H3O+ + e− → Hads | ||

| Heyrovsky | ||

| Hads + H3O+ + e− → H2 | ||

| Tafel | ||

| Hads + Hads → H2 (g) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).