1. Introduction

Prevention of health deterioration in CKD is necessary [

1] because it affects both physical and mental health [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Adopting an optimal combination of coping strategies may facilitate prevention of health deterioration in CKD [

7]. Educational interventions to promote coping strategies in patients on HD are effective for enhancing their physical, mental, and social function [

8], yet interventions cannot be implemented without adequate knowledge of the demographics-stress, demographics-coping, and stress-coping relationships [

9]. Therefore, there is a need for methodological improvements in how to study these relationships to address stress in kidney diseases [

10].

Considering the controversies regarding the evidence of relationships between sex and coping, Bruce et al. (2015) proposed that future studies should consider gender instead of sex to incorporate a psychological perspective rather than a reproductive perspective [

10]. However, Johnson et al. (2019) suggested that future studies specifically focused on sex have been needed to understand the coping strategies of persons on HD [

11].

Most research in HD patients has focused on sex (i.e., males vs. females) and stressors that consider the reproductive health of males [

11]. For example, a study was conducted in Asia on the links between stress and coping by using sex as a mediator [

12]. Exploring the sex difference between stress and coping provided evidence on how elderly male and female persons perceived and coped with their stress [

12]. However, further research has been needed involving other populations to validate the sex differences in the link between stress and coping, particularly for elderly groups [

12].

Identifying demographic characteristics and stressors for selecting corresponding effective coping strategies has been the foundation for planning intervention that is sensitive to patients’ needs [

11]. Inconsistencies in previous studies in the literature regarding the nature of the relationships between stress, coping, and demographics were prevalent, as reflected in the literature review that was part of the larger dissertation study. Considering the gaps, regarding the relationships between stress and coping variables as well as stress and demographics variables a need to study how stress may moderate the choice of coping strategy in managing HD or how a patient's demographic profile (see

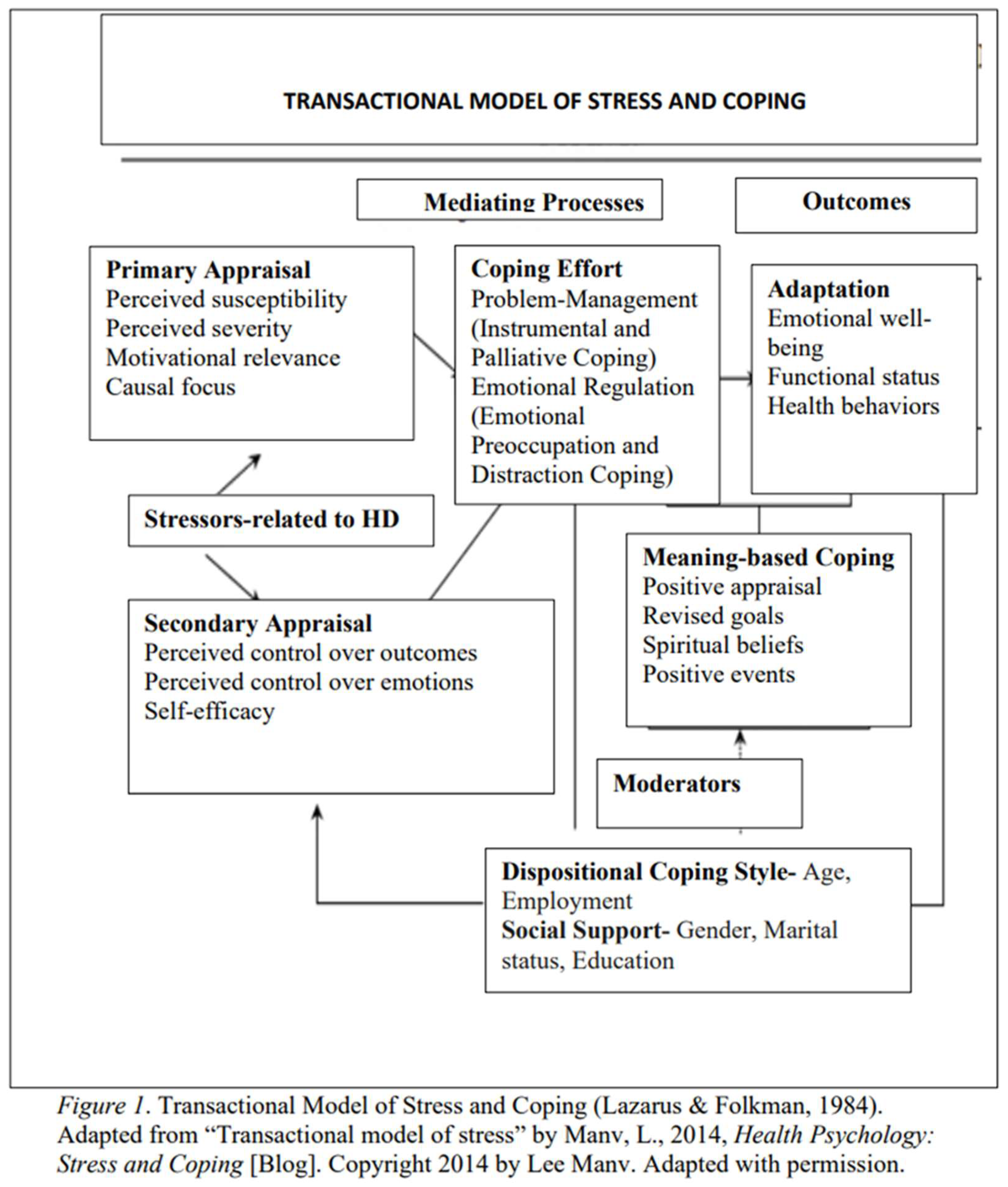

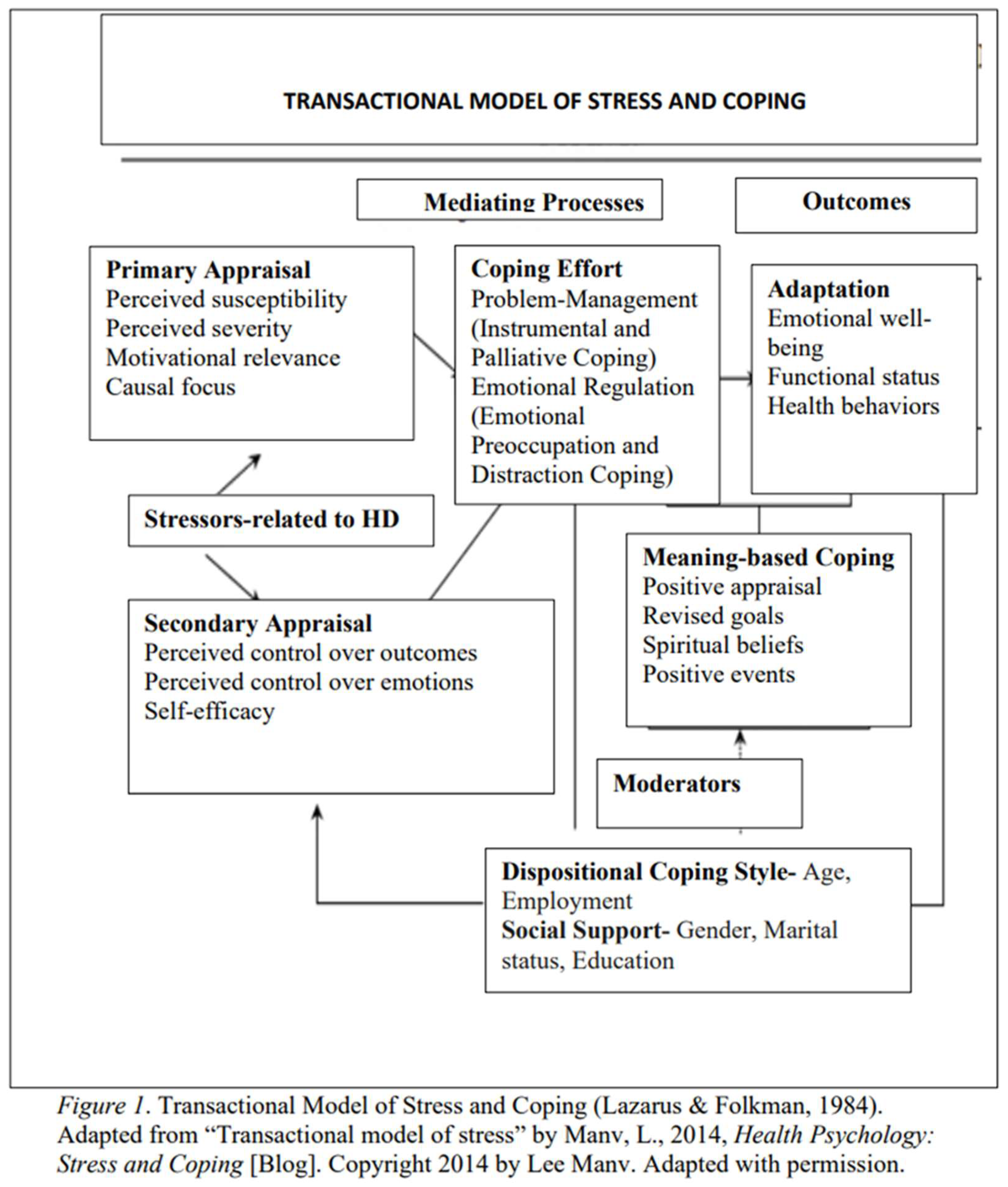

Appendix A) may introduce further variation into this relationship was identified. A quantitative research design to address the identified need was adopted. The research design was built on the theoretical approach of Lazarus and Folkman (1984) to guide such research [

13]. The transactional model of stress and coping “forms the metatheoretical foundation on which the cognitive theory of stress rests” ([

13], 1984, p. 293) and a model also used in the development of Coping with Health Injuries and Problems (CHIP, Endler et al., 1998) scale and Chronic Kidney Disease Stress Inventory (CKDSI) by Harwood et al., 2009). CHIP and CKDSI are the two instruments that were used in the data collection for the implemented study. The model claims that coping strategies have been determined by stressors that together lead to the appraisal of a stressful event ([

13,

14], see Figure 1, Appendix B). Based on this ideology that stressors determine the coping strategies used and the corresponding appraisal of a stressful event, the implemented study was conducted to identify the various types of coping strategies used in response to HD-related stress scores and to identify the patterns across different groups by demographics.

2. Materials and Methods

The quantitative, non-experimental, study design was used to assess if specific types of coping strategies are more prevalent as compared to others especially with the increase or decrease of stress scores and by sex type. Prediction of coping scores by demographic variables and stress scores was assessed using a series of inferential analyses. Data was collected in person while patients were receiving dialysis and in accordance with the ethics committee criteria of the hospital. Because no identifying information was collected from patients, the privacy of patients’ information was maintained. The study was approved by the IRBs of both the researcher’s institution and the hospital. Participants were men and women who self-reported between the ages of 20 and 70 and were on HD for CKD Stages 1-5 in a hospital of a Midwestern city in the United States. Purposeful sampling was done to recruit study participants. Purposeful sampling was used to ensure the sample met the eligibility criteria for the study. Participants were eligible to participate if they had been on HD for a minimum of 1 month and were currently receiving HD, with the assumption that study participants were coping with the stress of their illness, as some form of coping is common for addressing stress due to HD [

11]. Age groups within the study participants were organized by a range of age categories (see

Appendix A). Patients were accessed through the hospital protocol. Instruments used in the study were chosen based on their reliability and validity as evaluated in the scientific literature. Data were collected from the eligible participants after obtaining informed consent. Data analysis was conducted using descriptive and inferential analysis with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) v. 25.0 [

15].

G*Power (2017) was used to calculate the sample size necessary to achieve statistical power and generalizability to a larger population [

16]. A sample size calculation for a two-tailed multiple regression was performed for a fixed model

R-squared increase using a moderate effect size (

f = 0.15) with alpha set at 0.05 and power at 0.80. A sample size of 68 study participants was indicated through sample calculation as needed to achieve statistical power.

Although a sample size of 68 was calculated for maintaining statistical power and generalizability, the total number of patients attending nephrology clinics for HD at the target hospital was 80, thereby affecting the likelihood of recruiting the necessary sample size. Most patients regularly completed forms as part of their HD visits, which increased the likelihood of increased response rate. Generalizability of findings to larger populations may require consideration of other factors (i.e., factors not included for evaluation in this study), even if statistical power was met.

A letter of cooperation was finalized and signed by the hospital administration, followed by institutional review board (IRB) approval granted through the IRBs of A. T. Still University College of Graduate Health Studies and the hospital with an IRB # STUDY00001929. Research was conducted after obtaining IRB approvals. Data were collected through a primary data collection method (i.e., in-person survey administered by the nurses on floor at the time of in-patient dialysis in the dialysis unit).

Three instruments were used to collect data i.e., demographic data questionnaire (see

Appendix A); CHIP; and CKDSI. All items from CHIP and CKDSI instruments were used to collect data. Each item in the CHIP and CKDSI instruments was measured using a 4-point Likert-type scale. The demographic questionnaire included questions to measure age, sex, marital status, educational level, and employment status. The CHIP questionnaire was used because it is a reliable scale with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging in between 0.78-0.88 [

17]; and a valid scale as was assessed through a principal component analysis using varimax rotation to determine factor validity in addition to measuring construct validity [

18]. CHIP also has criterion validity as was assessed by comparing it with the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations and the Coping Strategy Indicator [

19]. The CKDSI was used to measure the perceived stress experienced corresponding to HD-related stressors in patients with CKD as it is a reliable and valid scale [

20]. The CKDSI scores for each item were added together to form a continuous variable with a continuous score for the study.

Data were collected in-person during the patients’ dialysis. Patients were screened for the study using two questions: “What is the type of your chronic renal disease?” and “What is the stage of your chronic kidney disease?” (See

Appendix A). Patients who indicated HD for CKD were included in the study. Patients with a diagnosis of CKD but not on HD were excluded because coping strategies for HD-related stressors were being evaluated. No potential participants meeting the eligibility were excluded for any reason. To increase recruitment without researcher bias, eligibility questions were used to define inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Eligible study participants were provided a copy of the informed consent. Verbal informed consent was obtained. Verbal permission to collect data was implied as a voluntary informed consent for participation in the study. Data was collected for a time of about three months until a sample size of 66 was reached. Data collection stopped at this point because there were no more eligible participants accessible to be surveyed.

The study investigator was responsible for the anonymous data collection and data storage security. Paper format data was collected at the end of the dialysis visit, placed in locked folders, transferred to locked drawers at the researcher’s on-site office location, and later converted into electronic files by manual data entry. Paper files were shredded after keeping paper-format data protected in locked drawers for a minimum of 1 year. Electronic files of data were secured in password-protected folders in REDCap™ on the researcher’s password-protected external organization’s computer at the time of study’s implementation.

Only completed surveys were analyzed for outcomes. Incomplete surveys were used for descriptive analyses only. Descriptive statistics included the percentages, frequencies, mode, and index of qualitative variation for each nominal demographic variable, the median and interquartile range or each ordinal demographic variable and the mean and standard deviation for each of the continuous variables (stress and coping strategies).

The Materials and Methods should be described with sufficient details to allow others to replicate and build on the published results. Please note that the publication of your manuscript implies that you must make all materials, data, computer code, and protocols associated with the publication available to readers. Please disclose at the submission stage any restrictions on the availability of materials or information. New methods and protocols should be described in detail while well-established methods can be briefly described and appropriately cited.

Research manuscripts reporting large datasets that are deposited in a publicly available database should specify where the data have been deposited and provide the relevant accession numbers. If the accession numbers have not yet been obtained at the time of submission, please state that they will be provided during review. They must be provided prior to publication.

3. Results

A response rate of 84.84% was observed. Generally, the participants were 60-69 years old (28.6%), male (64.3%), single (53.6%), and high school graduates or the equivalent (64.3%; see

Table 1).

The self-reported stress scores by the participants were more towards the lower values of total stress score (M = 0.89, SD = 0.51), meaning the sample could not be considered stressed. Considering coping strategies, the sample had the highest mean score for instrumental coping (M = 23.94, SD = 7.32), followed by palliative coping (M = 24.28, SD = 6.57), then distraction coping (M = 23.94, SD = 7.32), and finally emotional pre-occupation coping (M = 22.0847, SD = 8.09).

Correlation analysis of the independent variables (IVs) with the dependent variables (DVs) in nine research questions indicated that correlation values for age, marital status, and educational status were not moderate (i.e., either below 0.2 or above 0.7) and none of the correlations were significant in any of the nine research questions. IVs of age, marital status, and education were, therefore, not included in any of the regression models. Correlations of the IV of employment status were not only moderate but also statistically significant and were therefore, added to the regression models for predicting DVs of distraction coping, palliative coping, instrumental coping, and stress score in four different models. Correlation of employment status with emotional preoccupation was high but not statistically significant. Correlations of employment status with any of the three different coping strategies or the stress score did not appear to be significant in the regression models. Sex was another variable that was statistically correlated and had a moderate correlation with the stress but when added into the regression model did not

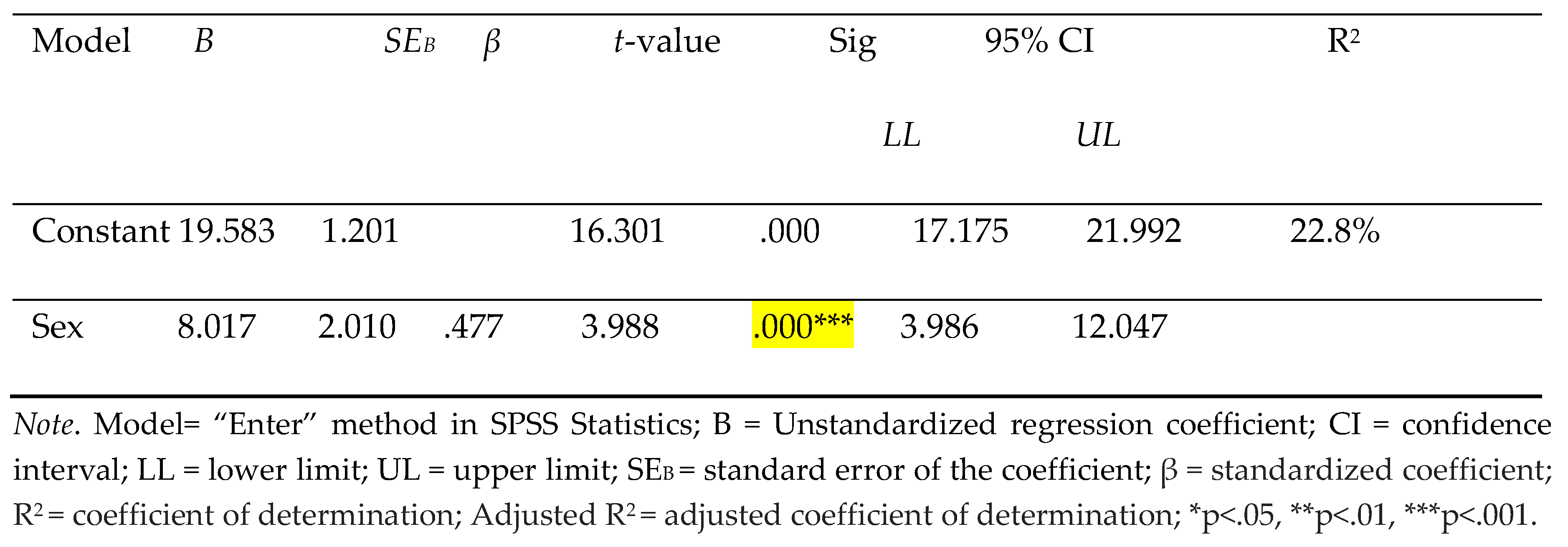

Sex and Emotional Pre-occupation

IV of sex statistically significantly predicted variations in emotional preoccupation coping. Sex was only fit to be added to the linear regression model for predicting variations in emotional pre-occupation. R2 for the overall model was 22.8% with an adjusted R2 of 21.3%, a small to moderate size effect [

21]. The linear 58 regression model statistically significantly predicted emotional pre-occupation coping, F(1, 54) = 15.904, p = .000, adj. R2 = .213. The variable of sex statistically significantly predicted variations in emotional pre-occupation, p < 0.001. The slope coefficient (B) of sex was statistically significantly different from 0 (zero) in the model. It can also be interpreted as meaning there was a linear relationship between sex and emotional preoccupation coping strategy. Females (comparison group) could be expected to have emotional coping scores 8 units greater than males (reference group), as B = 8.017 for sex in the model, p =.000 that explained 21% of the variance in the emotional pre-occupation coping strategy). Regression coefficients and standard errors were enlisted (see

Table 2).

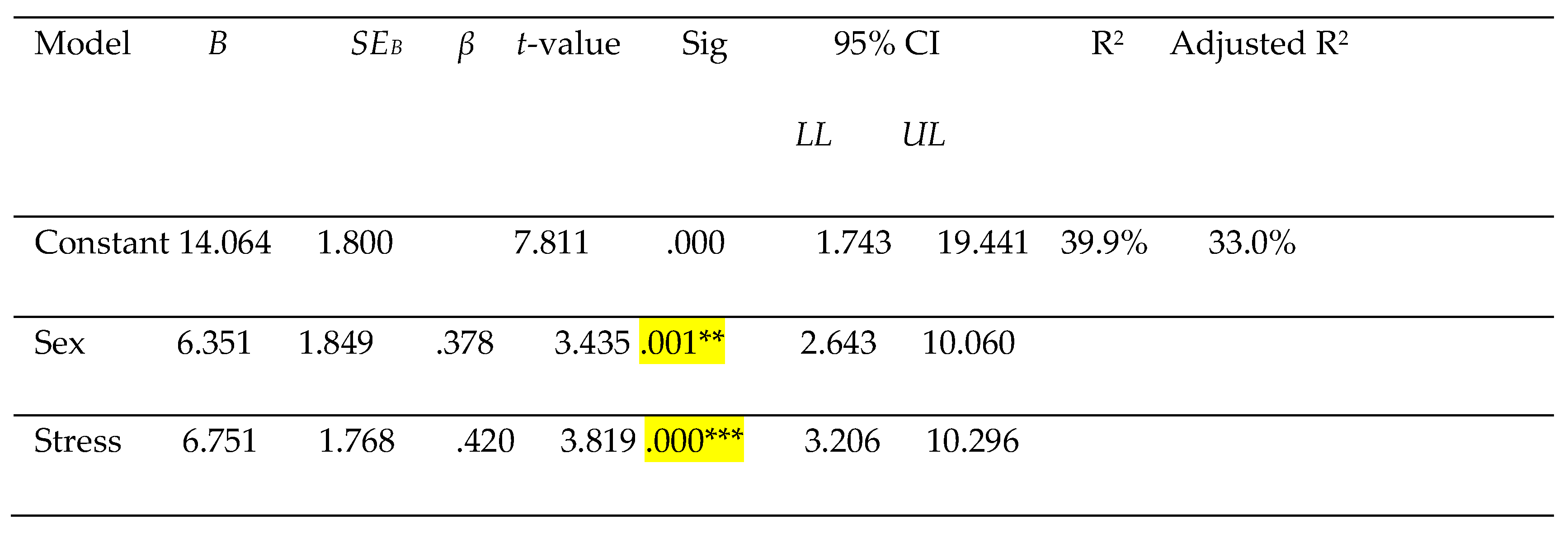

Sex, Stress, and Emotional Pre-occupation. Correlation values for sex were 0.477 and for total stress score were 0.509, p=.000 for both variables. Sex and stress score were only fit to be added to the multiple regression model for predicting variations in emotional pre-occupation. RI for the overall model was 39.4% with an adjusted R2 of 37.1%, a moderate size effect.[

21] The multiple regression model statistically significantly predicted emotional pre-occupation coping, F(2,53)=17.246, p=.000, adj. R

2=.371. The variable of sex and stress added statistically significantly added to the prediction of emotional pre-occupation, p < 0.001, that explained 33% of the variance in the emotional pre-occupation coping strategy. The slope coefficients (Bs) of sex and stress were statistically significantly different to 0 (zero) in the model. It can also be interpreted as meaning there was a linear relationship between sex and emotional pre-occupation coping strategy. Females could be expected to have coping scores 6.4 points higher than males when adjusted for stress levels, as B=6.351 for sex in the model, p=.001. For each 1-point increase in Stress Score, the Coping Score could be expected to increase 6.8 points when adjusted for Sex, where B=6.751 and p =.000. Regression coefficients and standard errors were enlisted (see

Table 3).

4. Discussion

Stress is a normal part of life and especially stress associated with chronic health conditions can be overwhelming.[

9,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Stress specifically holds more significance in HD patients because it increases the higher rates of mortality due to cardiovascular events in HD patients as compared to cardiovascular events in general patients without HD [

26].

Higher stress levels and corresponding higher needs to address stress in HD [

25], demands prevalence of coping strategies in HD patients, yet achieving adequate use of coping strategies requires learning and adopting adaptive coping strategies in some cases.[

27] The differences between men and women in the use of emotion-focused coping strategies have been reported [

9,

11,

28]. The observed similarities of significant relationships of sex/gender with emotional pre-occupation/emotion-focused coping strategies correspondingly refers to the fact that despite geographical distances and whether you consider gender or sex, the construct of sex/gender holds significance in association with emotion-centered coping strategies/emotional pre-occupation coping strategy. Women use more emotion-focused coping strategies which can be explained by the current finding that females as compared to males use more emotional pre-occupation coping strategy.[

9] Though emotion-focused coping often has been described as less effective than problem-focused coping, under certain circumstances, emotion-focused coping may be more productive than active coping responses (e.g., when a stressor cannot be changed like HD).

Self-blame, rumination and/or catastrophizing are examples of emotion-focused coping negative in nature that are related to higher depression scores.[

29] Positive reappraisal, on the other hand is a emotion-focused coping strategy positive in nature that is not only related with lower depression scores [

28] but also associated with lower levels of negative affect.[

30] Increased prevalence of emotion-focused coping in females in the current study could be an advantage for women undergoing HD, as adaptive use of emotion-oriented coping can help to decrease negative affect in women and increase positive affect in men.[

31] Furthermore, promoting adaptive emotion-focused coping facilitates prevention of harmful effects in HD patients [

24].

The phenomenon of understanding the significance of emotion-focused coping in patients on HD corresponds with the finding in the current study where, with an increase in stress, emotional pre-occupation coping strategy also increased. This finding was like the finding that emotion-focused coping increasingly prevailed in patients with CKD and/or patients on HD [

11,

32,

33]. Despite the increased prevalence of emotion-focused coping with increased stress in HD, emotion-focused coping consistently appeared to be more prevalent in women than men.

A need to assess if increasing emotional pre-occupation coping strategies in males would help to provide protective effects against the HD-related stress in males especially, because although males tended to engage in emotion-focused coping strategies less often, they appeared to experience better functional outcomes if they learn to use emotion-focused coping strategies [

34]. Up-skilling males in the use of emotion-focused strategies may provide them with an additional tool to manage their HD-related stress [

30]. Future research to confirm the role of emotional pre-occupation coping strategy as it relates to HD may be beneficial in planning and implementing interventions especially because emotional pre-occupation has considerable conceptual overlap with the emotion-oriented coping [

35]. Positive coping strategies in emotion-oriented coping like positive appraisal may need to be promoted for better stress management in HD patients and especially males. Therefore, future studies should consider increasing the prevalence of adaptive emotion-focused coping in men especially because men lack in emotion-focused coping to address stress. Increasing adaptive emotion-focused coping holds significance in the stress-management therapies as it can be used to increase self-care in patients on HD for ultimately increasing hope [

36].

The results of the study provided evidence-based information to health care providers involved in renal care management about the differences in the use of coping strategies that were reported from the study sample. Knowledge of variations in coping strategies may effectively enable health care providers to plan and implement interventions for the study sample. Directed interventions to increase the prevalence of a better combination of coping strategies may facilitate the promotion of positive behaviors, manage HD compliance, and increase the quality of physical, mental, and social functions.

Researchers may consider assessing factors that contribute to expected increased emotional pre-occupation in females on HD. Simultaneously, researchers may also assess if increased use of emotional pre-occupation is associated with decreased use of distraction coping, to assess if emotional pre-occupation coping strategy may be used as a facilitative coping strategy for minimizing the negative effects of negative coping strategies. It may also be assessed if increased emotional pre-occupation in females helps to decrease the stress related with HD, and thus, increases palliative coping and instrumental coping strategies in females on HD.

Multi-centered research to assess if the observed trends remain consistent across larger populations. A longitudinal study to measure the same relationships at different time points would help with the confirmability of findings. In addition, assessment of daily living stressors in addition to HD-related stressors may be done. Larger sample sizes may also lead to the identification of associations that were insignificant in the study.

5. Conclusions

Stress-coping mechanisms are important parameters in addressing hemodialysis management especially when variations in coping styles corresponding to HD-related stress prevail by sex. Future research studies may focus on implementing interventions to increase emotional pre-occupation coping as a defensive coping mechanism in males and decreasing EP in females as an avoidance coping strategy.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, S.A.; methodology, S.A.; C.A and M.M; software, S.A.; validation, S.A., C.A.; L.K. and M.M; formal analysis, S.A. and C.A.; investigation, S.A.; resources, S.A. and Z.Q.; data curation, S.A. and Z.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A.; writing—review and editing, S.A. and C.A; visualization, S.A.; supervision, C.A.; L.K. and M.M.; project administration, S.A. and Z.Q.; funding acquisition, N.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of SANFORD HEALTH (protocol code 00001929 and February 20, 2020).” for studies involving humans. At A.T. Still University “Ethical review and approval were waived for this study under Section 45CFR46.104(d)(2)(i).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy restrictions and ethical requirements of the participating organization.

Acknowledgments

Study was originally published as a part of the dissertation thesis at the Doctorate in Health Education (DHEd), A.T. Still University. I would like to acknowledge Lori Harwood for sharing the “Chronic Kidney Disease Stress Instrument (CKDSI)”. I am also very thankful to Kelli Owens for her invaluable help with the data collection process; Angela Robinson for helping me with the IRB submission; Amanda Mensing, for helping me with the REDCap, and Presley Melvin for her administrative assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Screening and Demographic Questionnaire

Screening Question:

What is the type of your chronic renal disease? Circle one.

a. Chronic Kidney Disease

b. End-Stage Renal Disease

Demographic Questionnaire:

Please circle the letter of the answer that describes you best:

1. What is the stage of your CKD?

a. Stage 1

b. Stage 2

c. Stage 3

d. Stage 4

e. Stage 5

2. How long have you been on chronic hemodialysis?

a. Less than 6 months

b. 6 months – less than 12 months

c. 1 year – less than 2 years

d. 2 years to less than 3 years

e. 3 years or more

3. What is your age group?

a. 18-29 years

b. 30-39 years

c. 40-49 years

91

d. 50-59 years

e. 60-69 years

f. 70-79 years

g. 80-89 years

h. 90-99 years

4. What is your sex?

a. Male

b. Female

5. What is your marital status?

a. Married

b. Unmarried

c. Widowed

6. What is your educational level?

a. Less than high school diploma or equivalent

b. High school diploma or equivalent

c. Bachelor’s degree

d. Higher than Bachelor’s degree

7. What is your employment status?

a. Unemployed

b. Employed

c. Retired

Appendix B

References

- Honeycutt, A. A.; Segel, J. E.; Zhuo, X.; Hoerger, T. J.; Imai, K.; Williams, D. Medical costs of CKD in the Medicare population. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013, 24, 1478–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Chronic kidney disease in the United States; 2019 [PDF file]. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/kidneydisease/pdf/2019_National-Chronic-Kidney-DiseaseFact-Sheet.pdf.

- Herlin, C.; Wann-Hanson, C. The experience of being 30-45 years of age and depending on hemodialysis treatment: A phenomenological study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2010, 24, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liakopoulos, V.; Roumeliotis, S.; Gorny, X.; Dounousi, E.; Mertens, P. R. Oxidative stress in hemodialysis patients: A review of the literature. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017, 2017, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naderifar, M.; Tafreshi, M. Z.; Ilkhani, M.; Kavousi, A. The outcomes of stress exposure in hemodialysis patients. J Renal Inj Prev. 2017, 6, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otte, J.; Netten, J. V.; Woittiez, A. J. The association of chronic kidney disease and dialysis treatment with foot ulceration and major amputation. J Vasc Surg. 2015, 62, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cukor, D.; Cohen, S. D.; Peterson, R. A.; Kimmel, P. L. Psychosocial aspects of chronic disease: ESRD as a paradigmatic illness. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007, 18, 3042–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehkordi, L. M.; Shahgholian, N. An investigation of coping styles of hemodialysis patients. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2013, 18, 42–46. Available online: http://www.ijnmrjournal.net/. [PubMed]

- Harwood, L.; Wilson, B.; Sontrop, J. Sociodemographic differences in stressful experience and coping amongst adults with chronic kidney disease. J Adv Nurs. 2011, 67, 1779–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, M. A.; Griffith, D. M.; Thorpe, R. J. Stress and the kidney. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2015, 22, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.; Crane, P. B.; Neil, J.; Christiano, C. Coping with intradialytic events and stress associated with hemodialysis. Nephrol Nurs J. 2019, 46, 13–21. Available online: https://annanurse.org/resources/products/nephrology-nursing-journal.

- Yeh, S. J.; Huang, C. H.; Chou, H. C.; Wan, T. H. Gender differences in stress and coping among elderly patients on hemodialysis. Sex Roles. 2009, 7, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S.; Folkman, S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York, NY: Springer, USA, 1984. pp.293.

- Manv, L. Health psychology: Stress and coping [Blog]. 2014. Available online: http://leemanibnotes.blogspot.com/2014/04/health-psychology-stress-and-coping.htm.

- lIBM Analytics. What is IBM SPSS? n.d. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/analytics/us/en/technology/spss#what-is-spss.

- Heinrich Heine Universität Düsseldorf. G*Power: Statistical power analyses for Windows and Mac. (n.d.). Available online: http://www.psychologie.hhu.de/arbeitsgruppen/allgemeine-psychologie-undarbeitspsychologie/gpower.html.

- Kehler, M. D.; Hadjistavropoulos, H. D. Is health anxiety a significant problem for individuals with multiple sclerosis? J Behav Med. 2009, 32, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endler, N. S., Parker, J. A. Coping with health injuries and problems (CHIP): Manual. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems Inc; 2000.

- Hadjistavropoulos, H.; Asmundson, G.; Norton, G. Validation of the coping with health, injuries, and problems scale in a chronic pain sample. Clin J Pain. 1999, 15, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harwood, L.; Wilson, B.; Locking-Cusolito, H.; Sontrop, J.; Spittal, J. Stressors and coping in individuals with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Nurs J. 2009, 36, 265–301. Available online: https://www.annanurse.org/resources/products/nephrology-nursing-journal. [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). New York: Psychology Press, USA, 1988.

- Gorji, M. H.; Mahdavi, A.; Janati, Y.; Illayi, E.; Yazdani, J.; Setareh, J.; et al. Physiological and psychosocial stressors among hemodialysis patients in educational hospitals of northern Iran. Indian J Palliat Care. 2013, 19, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leghari, N.; Amin, R.; Akram, B.; Asadullah, M. A. Hemodialysis; psychosocial stressors in patients undergoing. Professional Med J. 2015, 22, 762–766. Available online: http://www.theprofesional.com/index.php/tpmj. [CrossRef]

- Mollahadi, M.; Tayyebi, A.; Ebadi, A.; Daneshmandi, M. Comparison of anxiety, depression and stress among hemodialysis and kidney transplantation patients. Irani J Crit Care Nurs. 2010, 2, 153–156. Available online: http://www.inhc.ir.

- Niihata, K.; Fukuma, S.; Akizawa, T.; Fukuhara, S. Association of coping strategies with mortality and health-related quality of life in hemodialysis patients: The Japan Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. PLoS One. 2017, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, M.; Mangano, M.; Stucchi, A.; Ciceri, P.; Conte, F.; Galassi, A. Cardiovascular disease in dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018, 33 (Suppl. 3), iii28–iii34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, M.; Morowatisharifabad, M. A.; Mehrabi, Y.; Zare, S.; Askari, J.; Alizadeh, S. What are the hemodialysis patients’ style in coping with stress? A directed content analysis. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery 2019, 7, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M. M.; Al Nazly, E. K. Hemodialysis: Stressors and coping strategies. Psychol Health Med. 2015, 20, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garnefski, N.; Teerds, J.; Kraaij, V.; Legerstee, J.; van den Kommer, T. Cognitive emotion regulation strategies and depressive symptoms: Differences between males and females. Pers Individ Dif. 2004, 36, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnefski, N.; Kraaij, V. Relationships between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and depressive symptoms: A comparative study of five specific samples. Pers Individ Dif. 2006, 40, 1659–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juth, V.; Dickerson, S. S.; Zoccola, P. M.; Lam, S. Understanding the utility of emotional approach coping evidence from a laboratory stressor and daily life. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2015, 28, 50–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deter, H. C. Psychosocial interventions for patients with chronic disease. Biopsychosoc Med. 2012, 6, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehkordi, L. M.; Shahgholian, N. An investigation of coping styles of hemodialysis patients. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2013, 18, 42–46. Available online: http://www.ijnmrjournal.net/. [PubMed]

- El-Shormilisy, N.; Strong, J.; Meredith, P. J. Associations among gender, coping patterns and functioning for individuals with chronic pain: A systematic review. Pain Res Manag. 2015, 20, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J. A.; Endler, N. S. Coping with coping assessment: A critical review. Eur J Pers. 1992, 6, 321–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorgholami, F.; Abdollahifard, S.; Zamani, M.; Jahromi, M. K.; Jahromi, Z. B. The effect of stress management training on hope in hemodialysis patients. Glob J of Health Sci. 2016, 8, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Sample Demographics.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Sample Demographics.

Table 2.

Linear Regression Results for Sex and Emotional Pre-occupation Coping.

Table 2.

Linear Regression Results for Sex and Emotional Pre-occupation Coping.

Table 3.

Multiple Regression Results for Sex, Stress and Emotional Pre-occupation Coping.

Table 3.

Multiple Regression Results for Sex, Stress and Emotional Pre-occupation Coping.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).