Submitted:

05 September 2023

Posted:

06 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

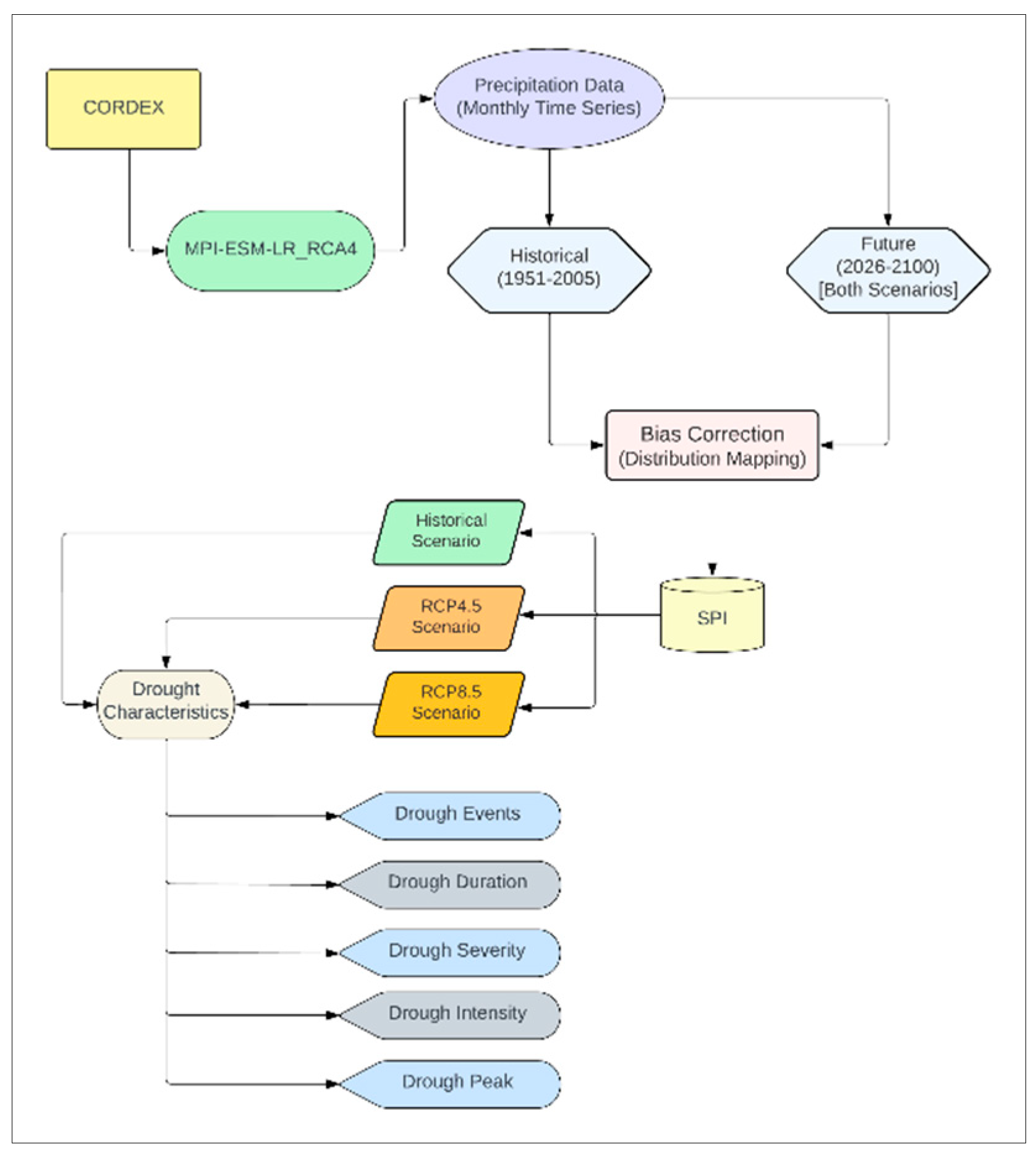

2. Methodology

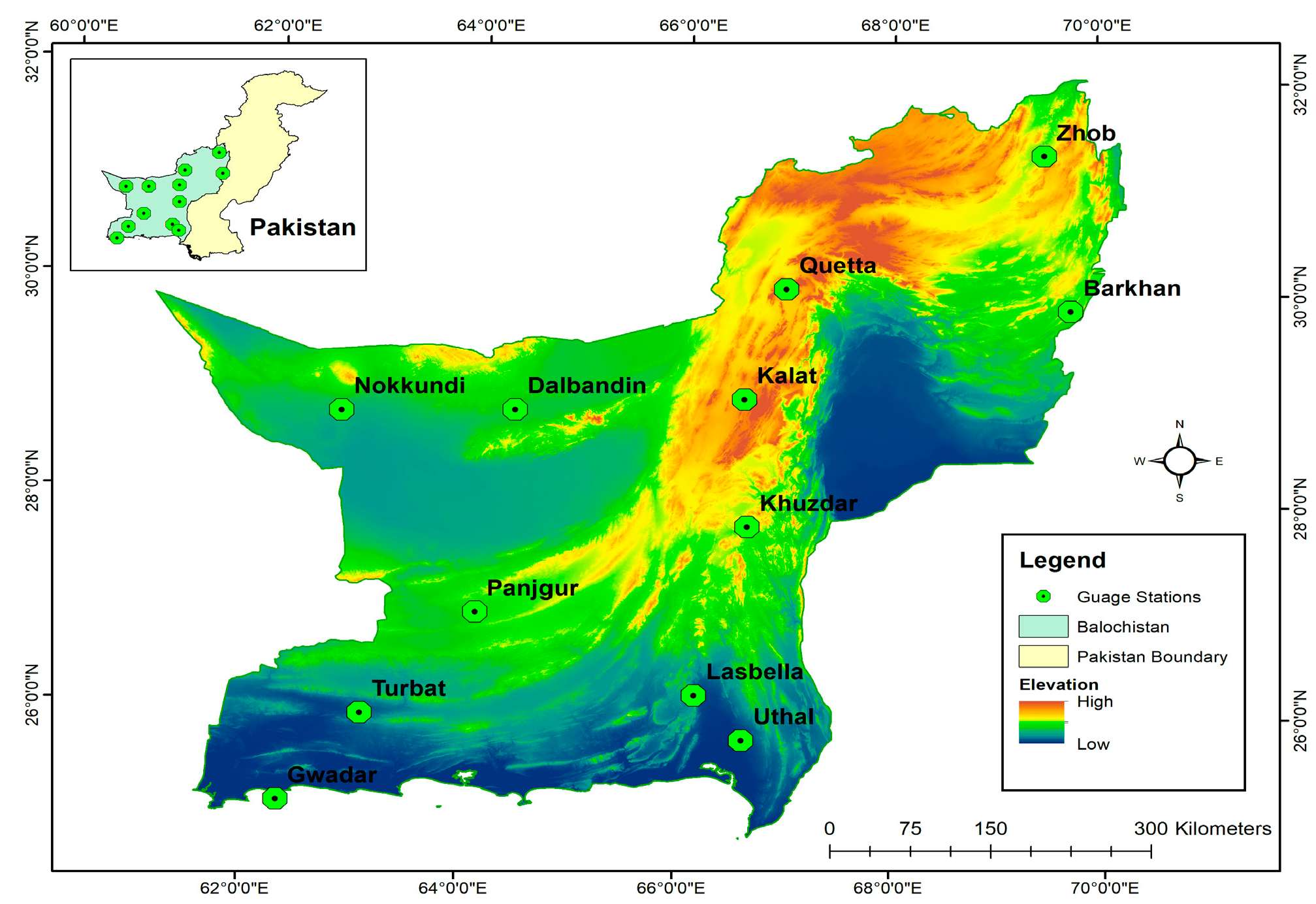

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Dataset

2.3. Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI)

| SPI | SPI category |

|---|---|

| ≥ 2.00 | Extremely wet |

| 1.50 to 1.99 | Severely wet |

| 1.00 to 1.49 | Moderately wet |

| 0 to 0.99 | Mildly wet |

| -0.99 to 0 | Mild drought |

| -1.49 to -1.00 | Moderate drought |

| -1.99 to -1.50 | Severe drought |

| ≤ -2.00 | Extreme drought |

2.4. Drought Characteristics

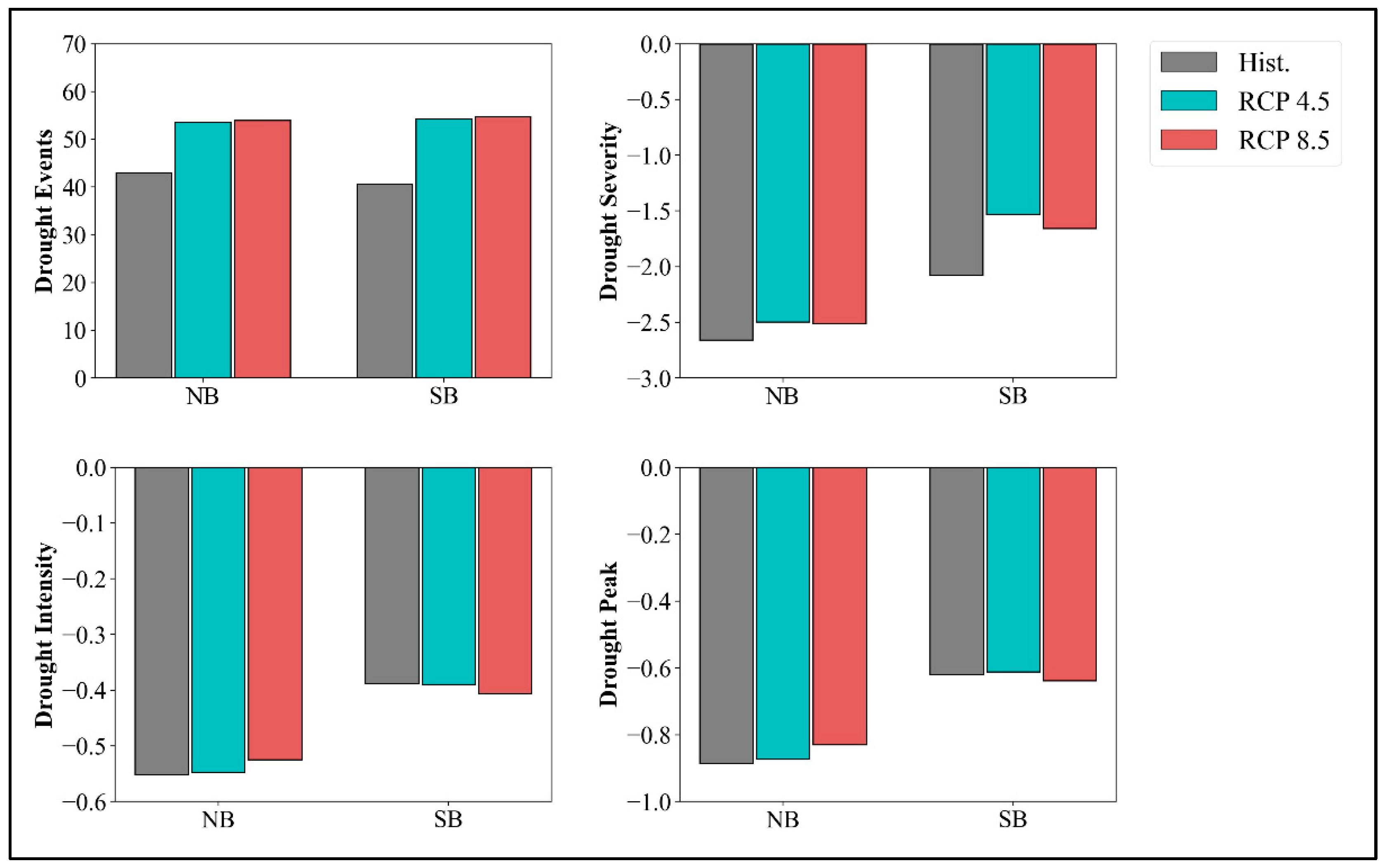

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusion

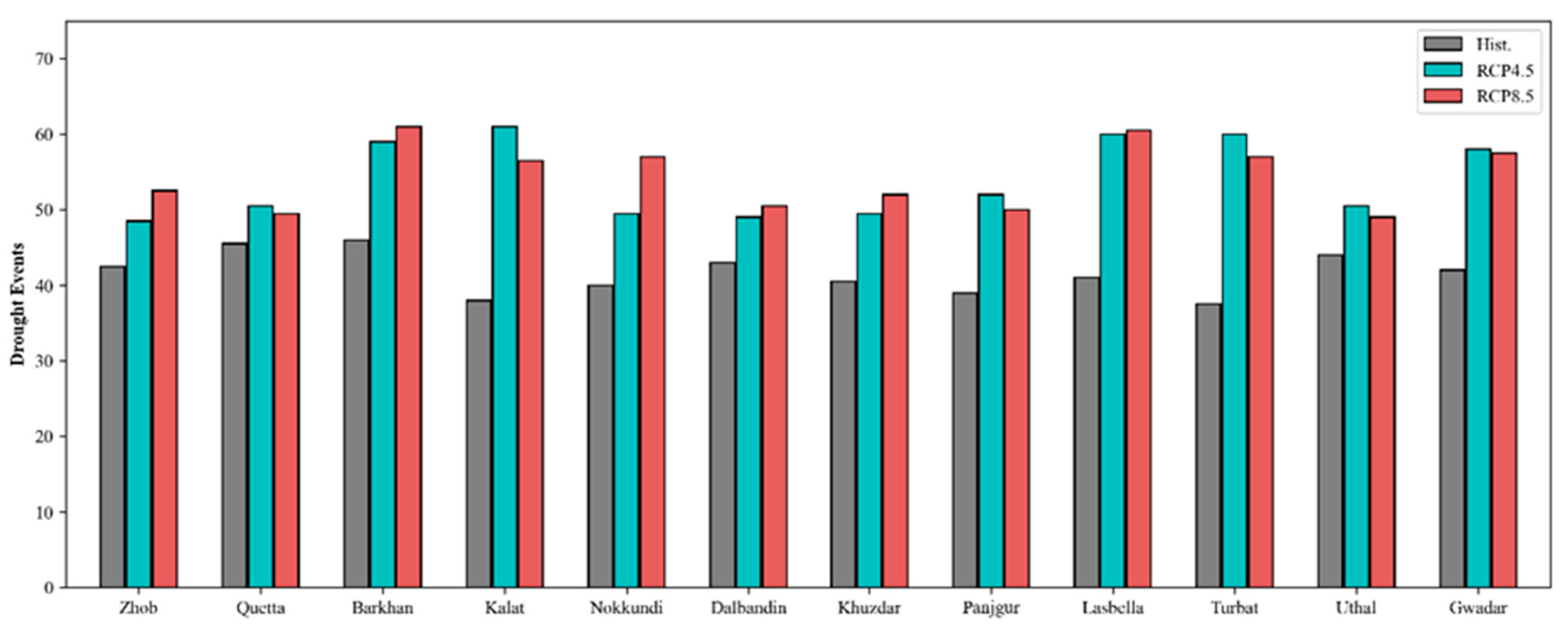

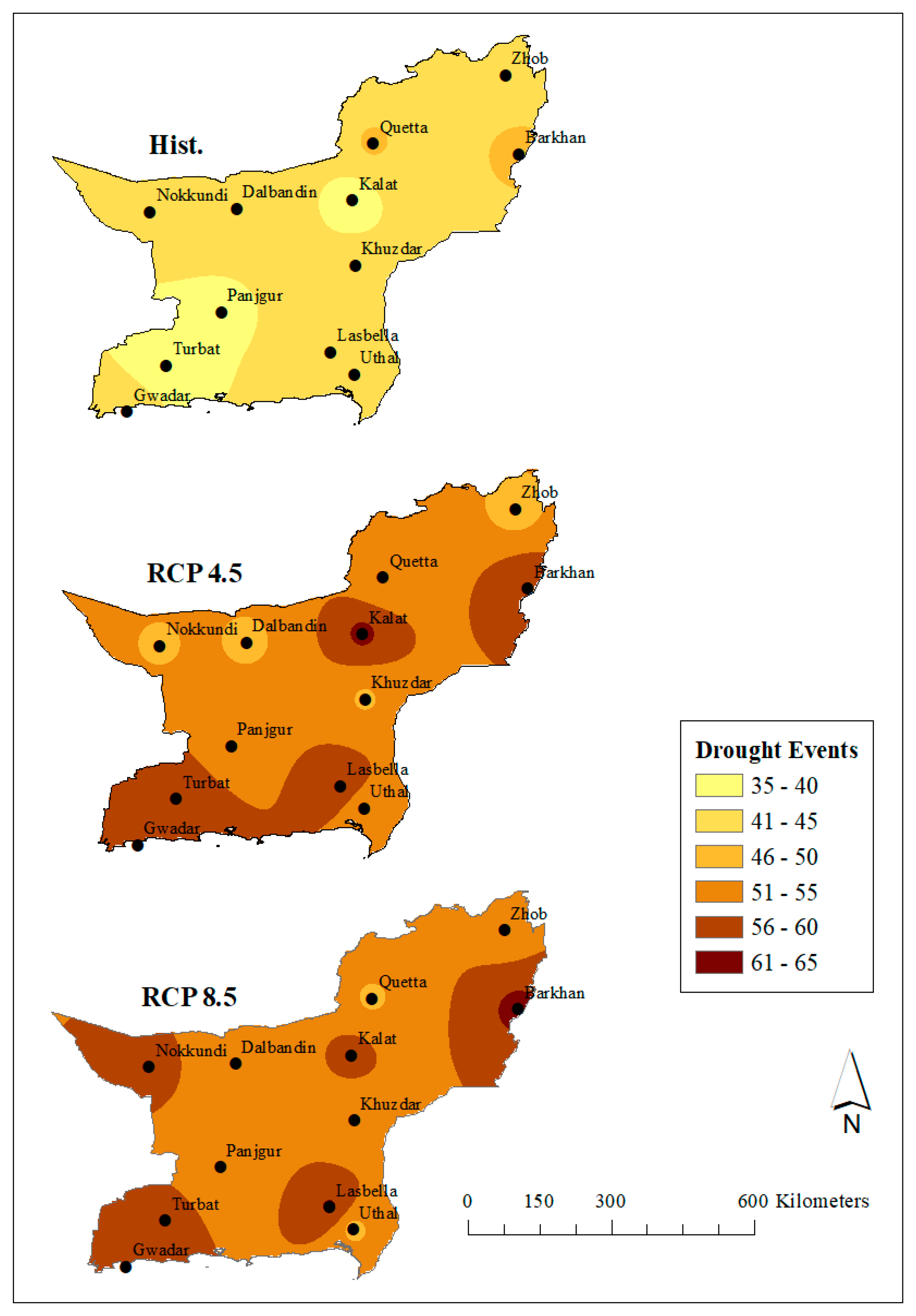

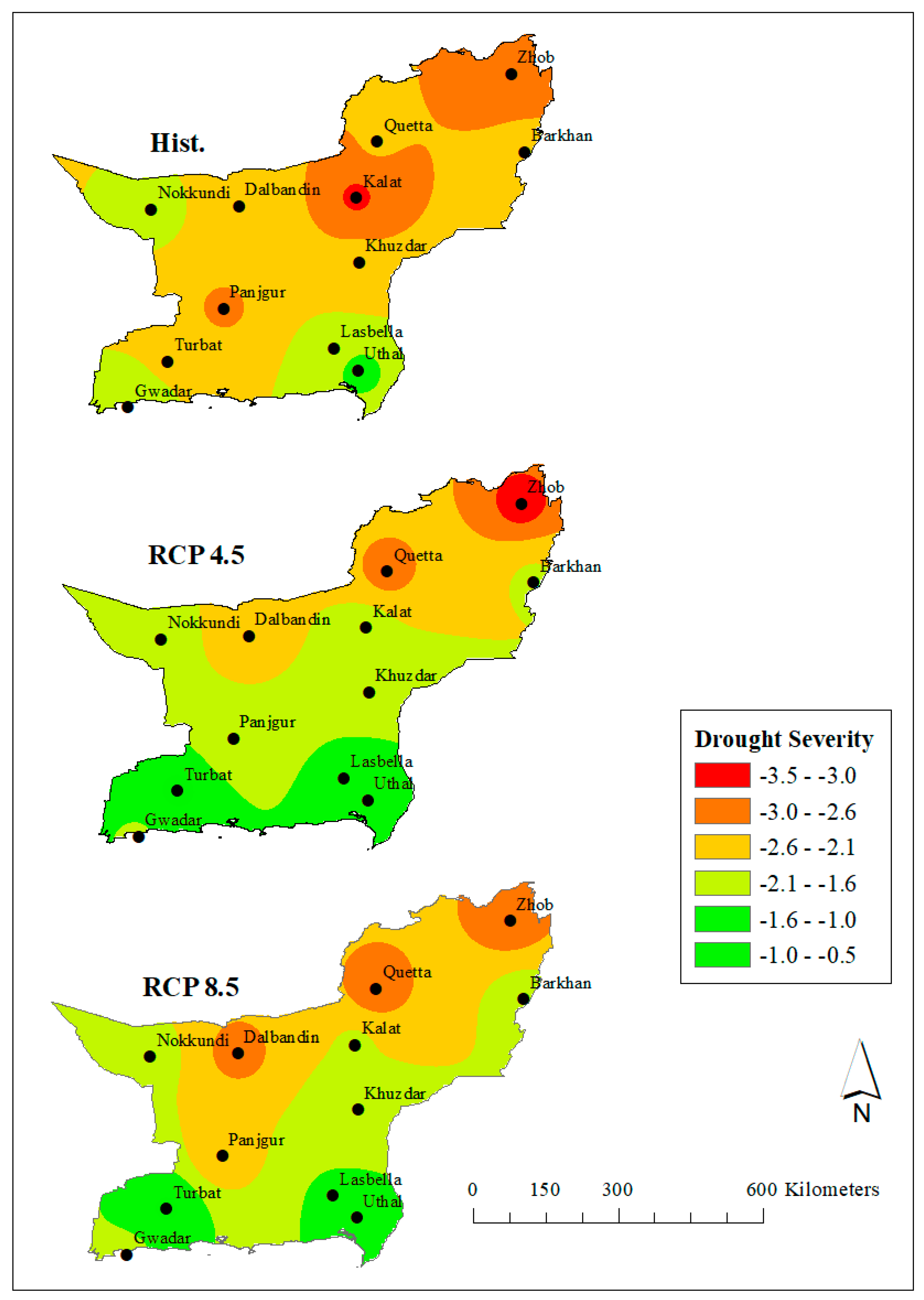

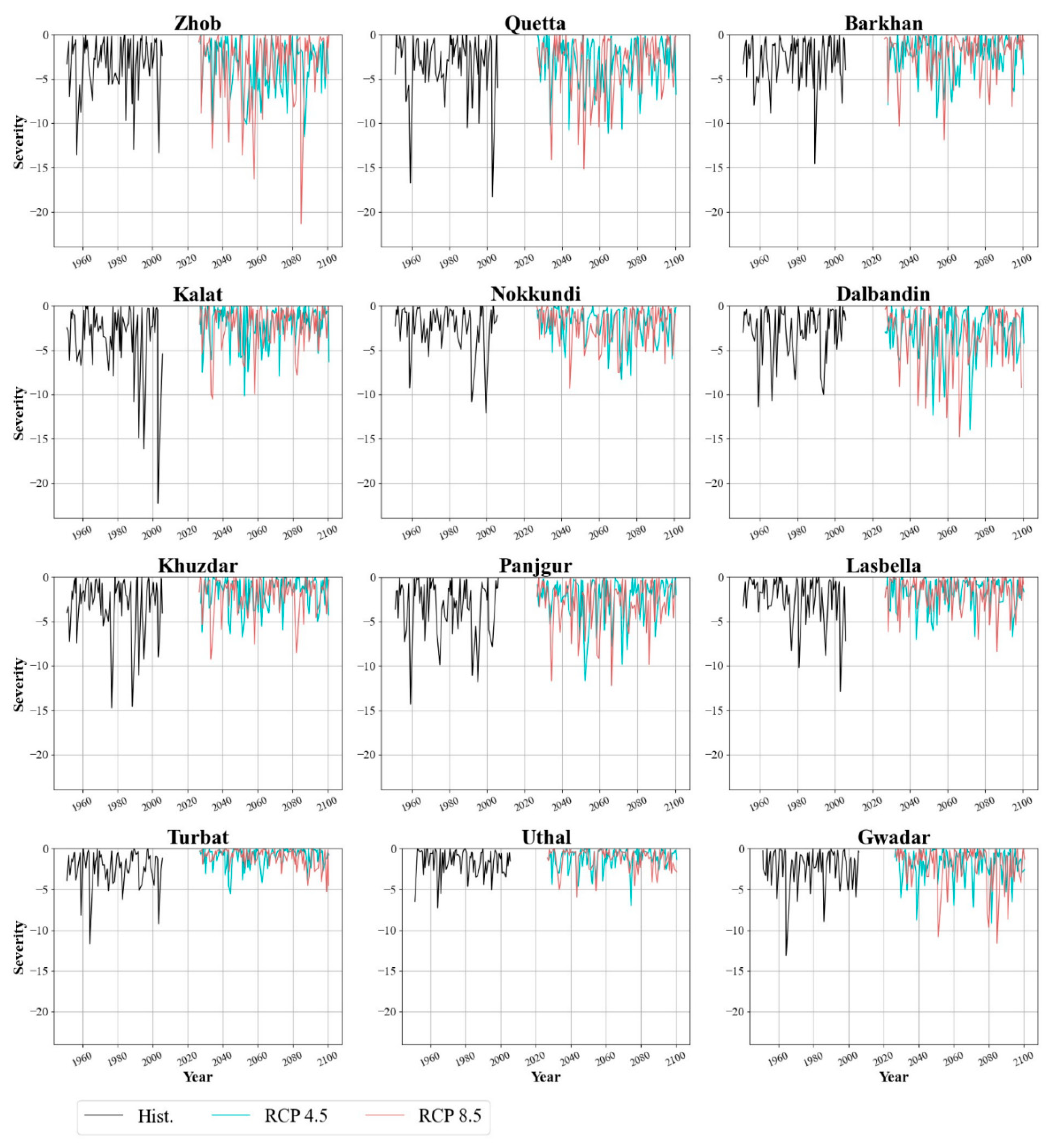

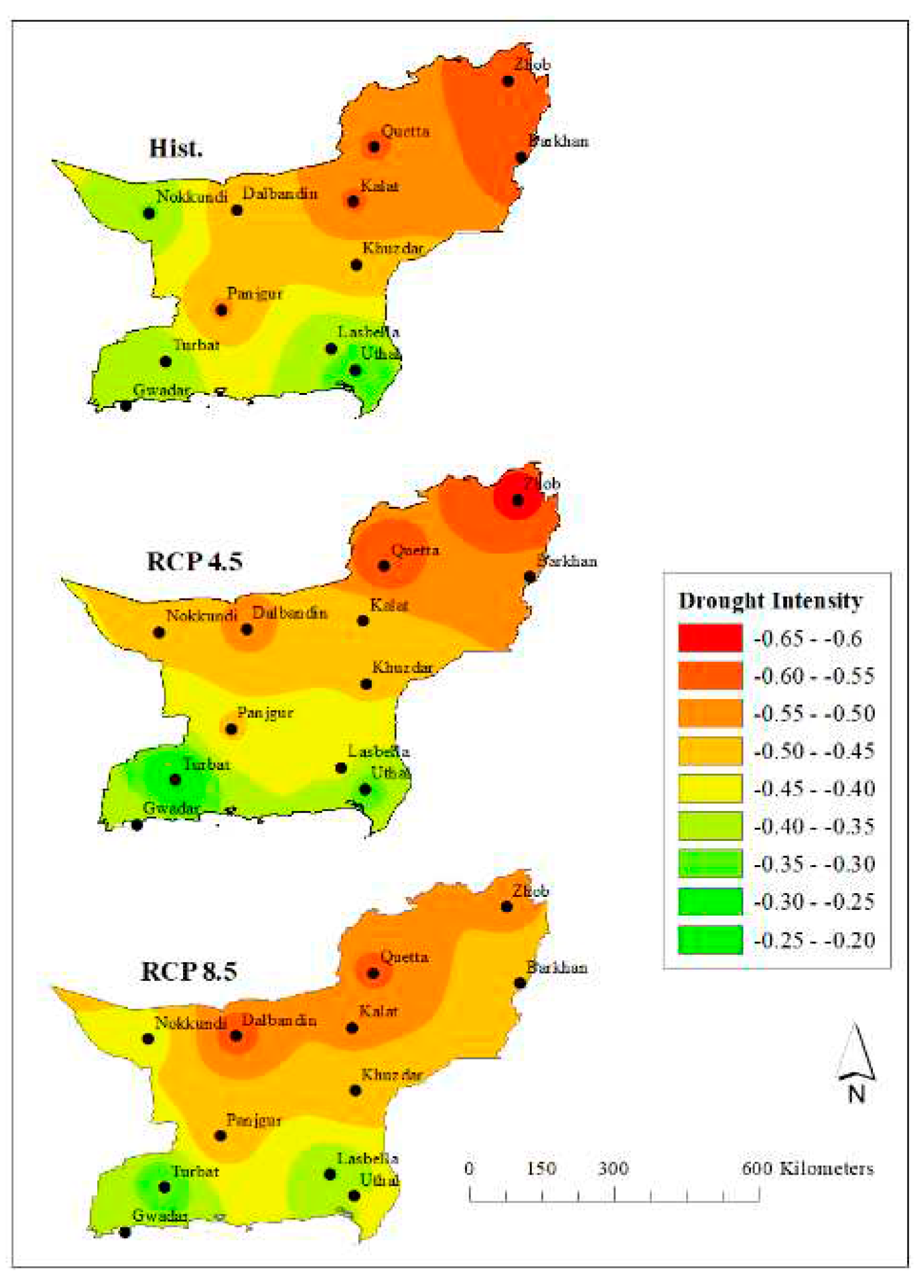

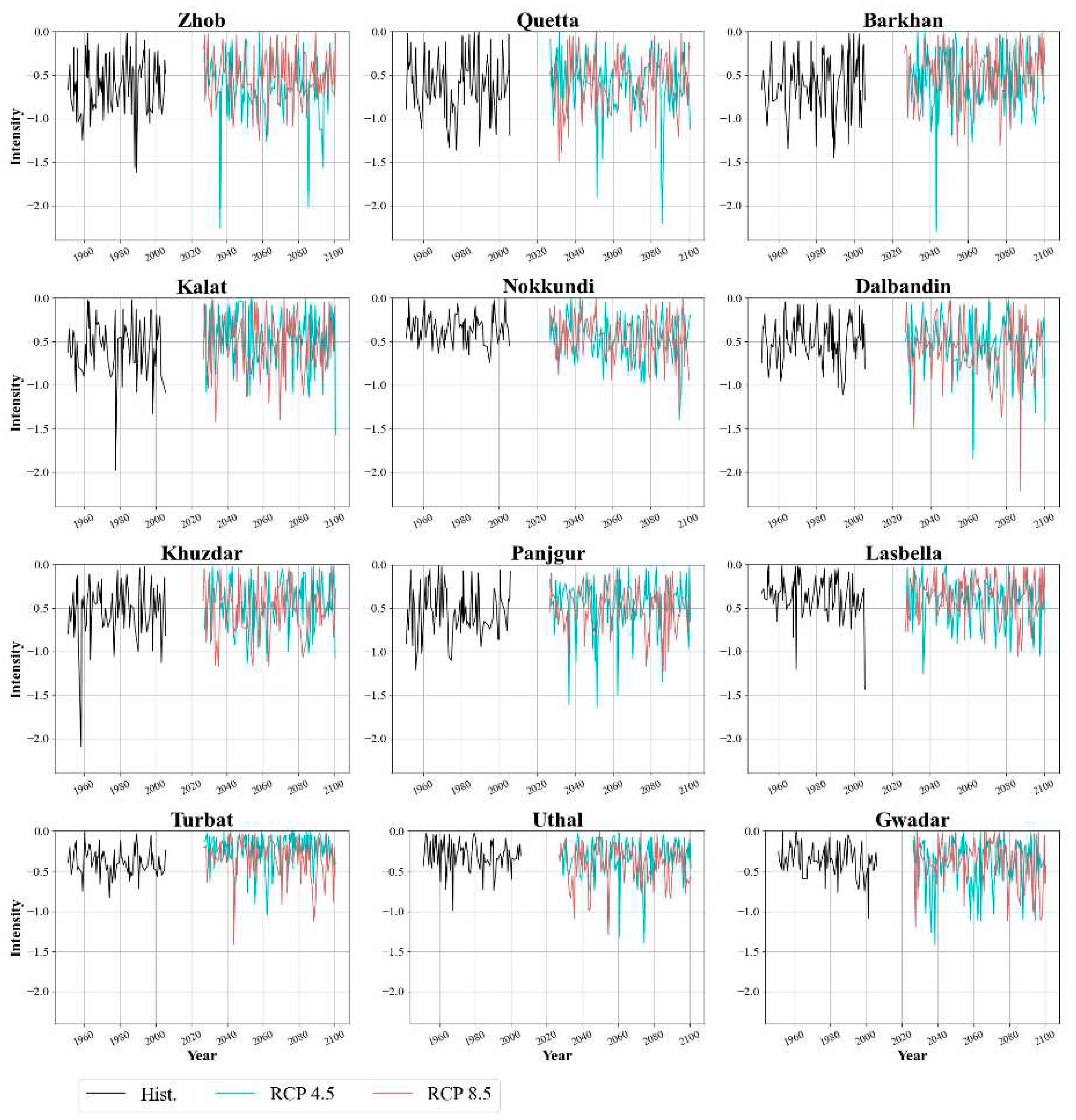

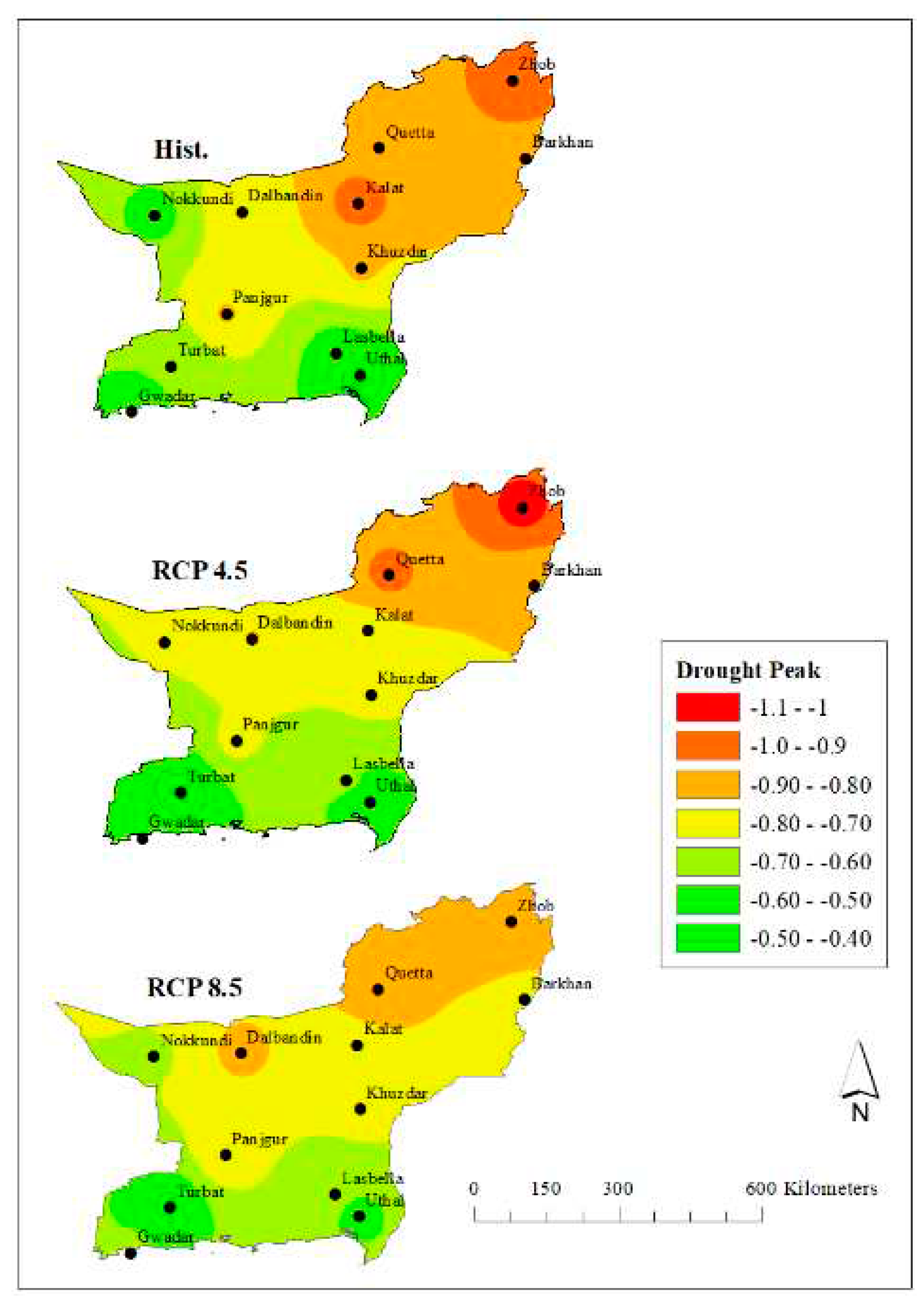

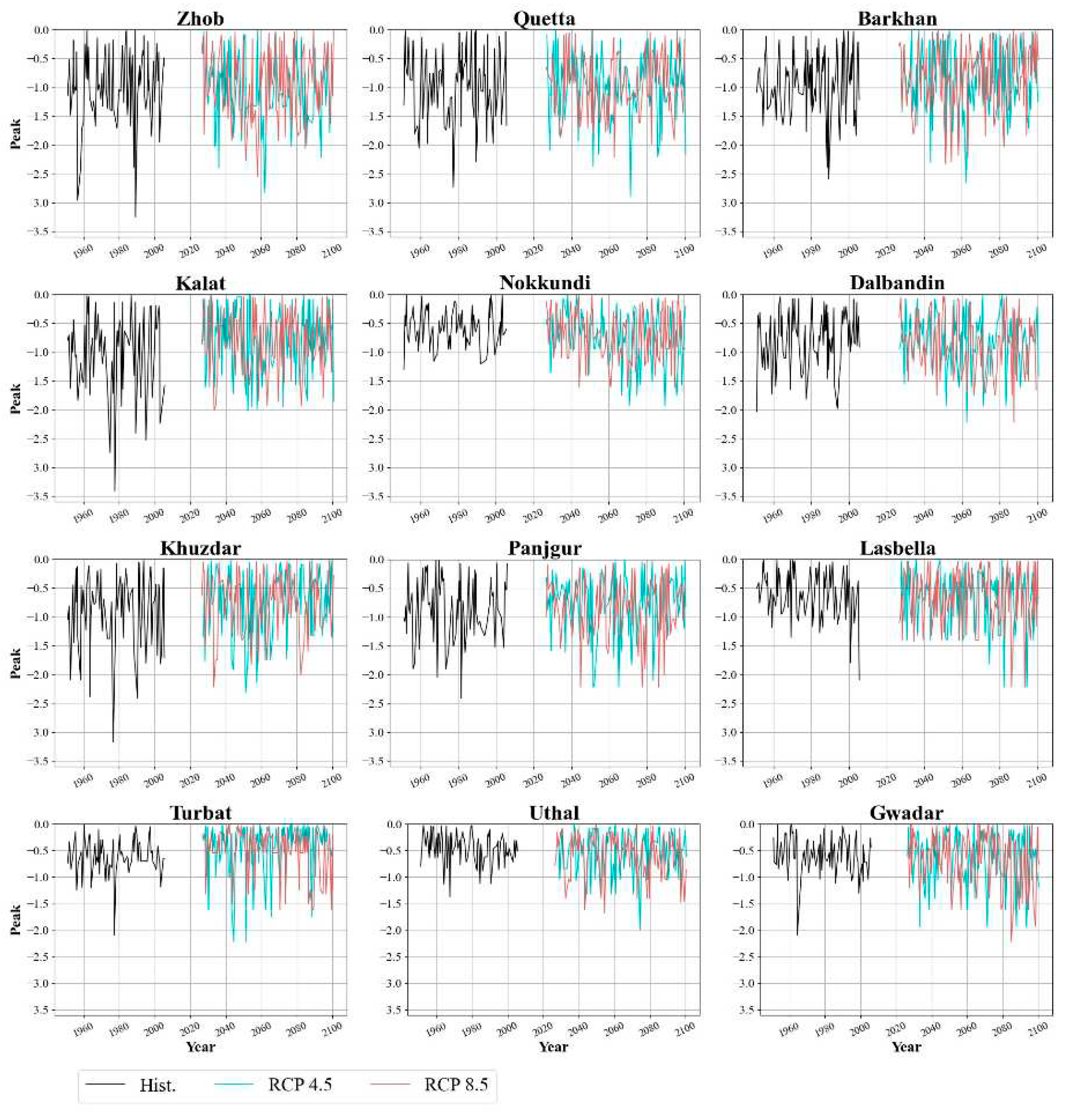

- All stations experienced numerous drought conditions in different years and are likely to suffer moderate, severe, and extremely dry conditions, in the future under both scenarios.

- The stations in the NB region faced higher droughts in the historical period. Moreover, droughts are projected to increase in the future under both scenarios. It shows that the drought characteristics (severity, intensity, and peaks) are projected to be more in the NB region under both scenarios.

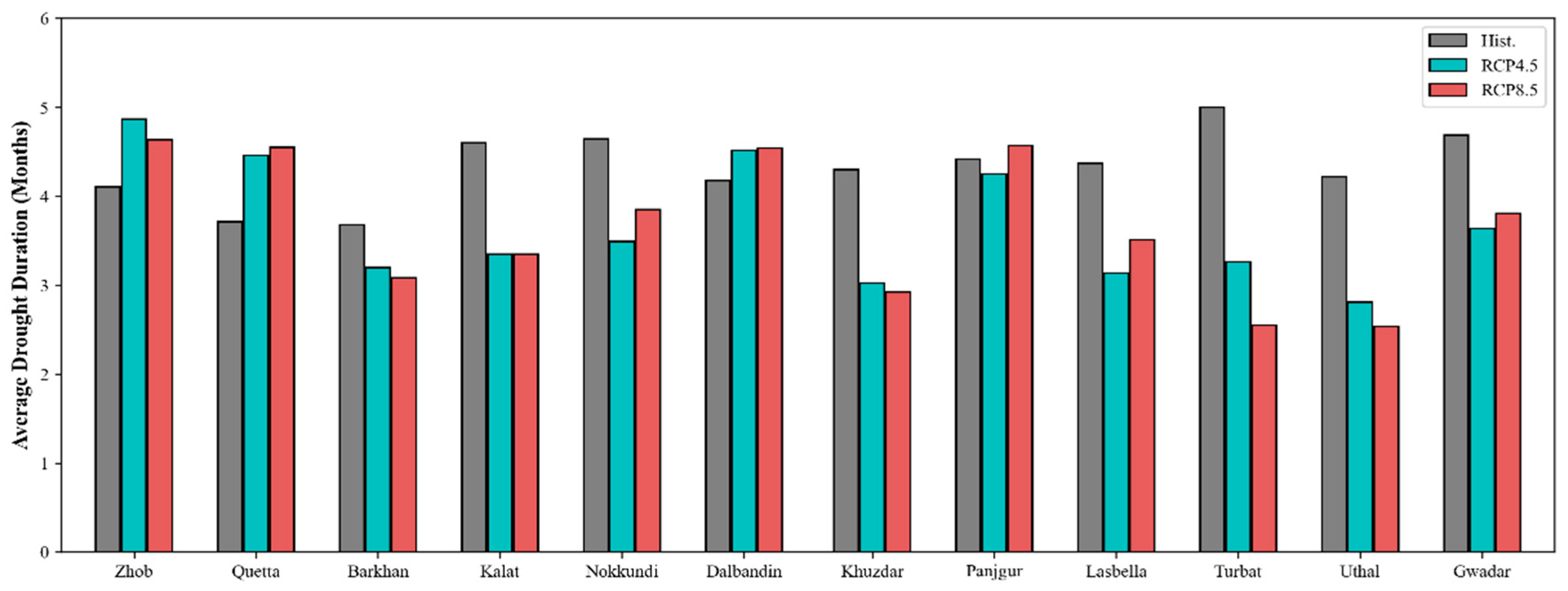

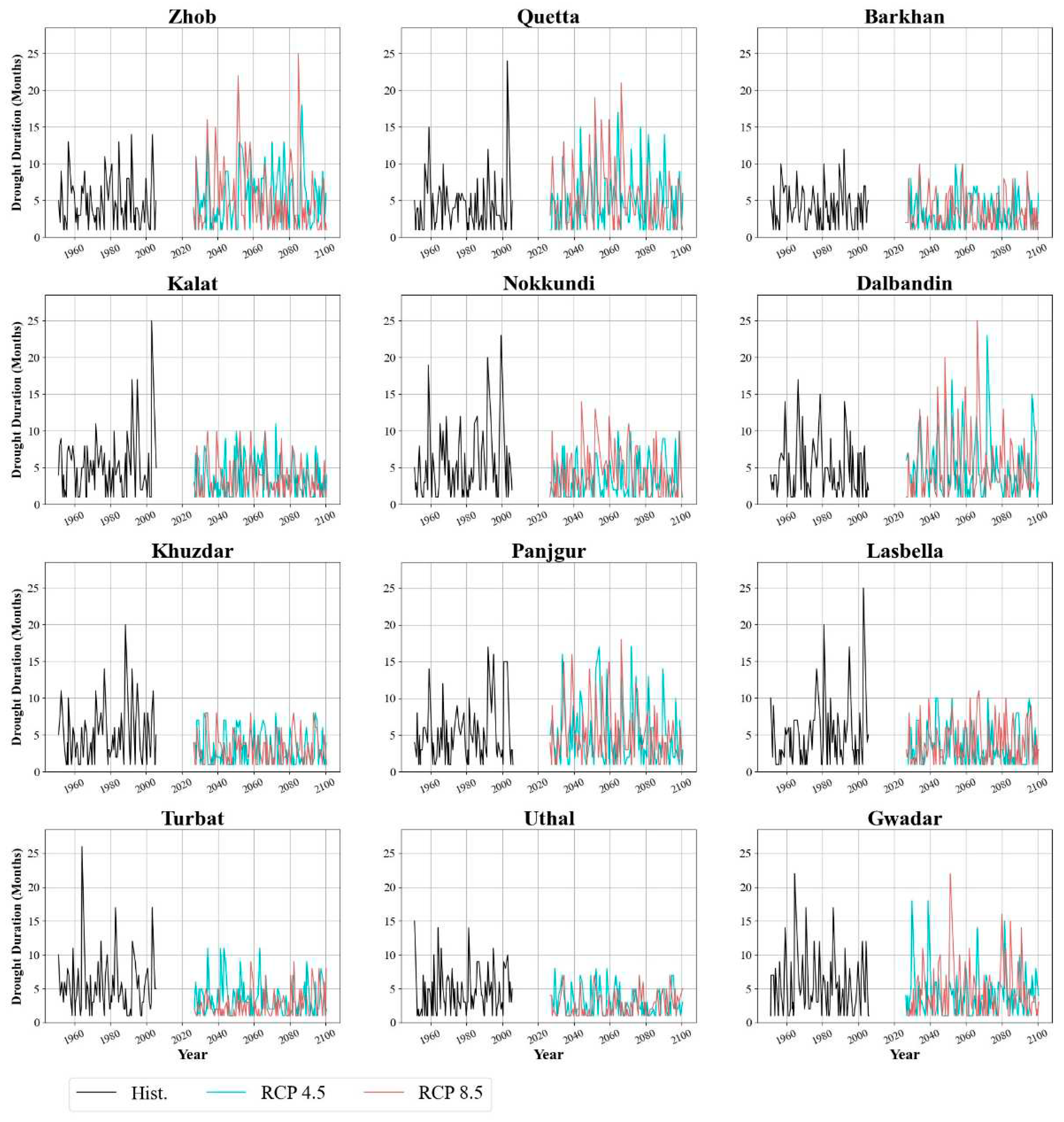

- The drought duration seems to be reduced with an increase in the number of drought events and vice versa in the whole region.

- At most stations, the average drought duration for historical and future scenarios is calculated as 3-5 months.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GRR The Global Risks Report 2022; 2022; ISBN 9782940631094.

- Farooq, U.; Ahmad, M.; Jasra, A.W. Natural Resource Conservation, Poverty Alleviation, and Farmer Partnership. Pak. Dev. Rev. 2007, 46, 1023–1049. [CrossRef]

- Naz, F.; Dars, G.H.; Ansari, K.; Jamro, S.; Krakauer, N.Y. Drought Trends in Balochistan. Water (Switzerland) 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, V. Pakistan’s Alarming Water Crises: Country to Run Out of Clean Water By 2025. 2018.

- Wang, S.-Y.; Davies, R.E.; Huang, W.-R.; Gillies, R.R. Pakistan’s Two-Stage Monsoon and Links with the Recent Climate Change. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2011, 116, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Salma, S.; Rehman, S.; Shah, M.A. Rainfall Trends in Different Climate Zones of Pakistan. Pakistan J. Meteorol. 2012, 9, 37–47.

- Ullah, I.; Ma, X.; Yin, J.; Omer, A.; Habtemicheal, B.A.; Saleem, F.; Iyakaremye, V.; Syed, S.; Arshad, M.; Liu, M. Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Meteorological Drought Variability and Trends (1981–2020) over South Asia and the Associated Large-Scale Circulation Patterns. Clim. Dyn. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Z.; Shahid, S.; Ahmed, K.; Ismail, T.; Nawaz, N. Spatial Distribution of the Trends in Precipitation and Precipitation Extremes in the Sub-Himalayan Region of Pakistan. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2019, 137, 2755–2769. [CrossRef]

- Dars, G.H.; Najafi, M.R.; Qureshi, A.L. Assessing the Impacts of Climate Change on Future Precipitation Trends Based on Downscaled CMIP5 Simulations Data. Mehran Univ. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2017, 36, 385–394. [CrossRef]

- Wilhite, D.A.; Sivakumar, M.V.K.; Pulwarty, R. Managing Drought Risk in a Changing Climate: The Role of National Drought Policy. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2014, 3, 4–13. [CrossRef]

- Wilhite, D.A. Drought as a Natural Hazard: Concepts and Definitions. Droughts 2000, 33–33. [CrossRef]

- Keyantash, J. The Quantification of Drought: An Evaluation of Drought Indices. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2002, 1167–1180.

- Lee, E.J.; Azam, M.; Rehman, S.U.; Waseem, M.; Anjum, M.N.; Afzal, A.; Cheema, M.J.M.; Mehtab, M.; Latif, M.; Ahmed, R.; et al. Spatio - Temporal Variability of Drought Characteristics across Pakistan. Paddy Water Environ. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Jamro, S.; Channa, F.N.; Dars, G.H.; Ansari, K.; Krakauer, N.Y. Exploring the Evolution of Drought Characteristics in Balochistan, Pakistan. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.; Routray, J.K. Spatio-Temporal Characteristics of Precipitation and Drought in Balochistan Province, Pakistan. Nat. Hazards 2015, 77, 229–254. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.; Shahid, S.; Harun, S. bin; Wang, X. jun Characterization of Seasonal Droughts in Balochistan Province, Pakistan. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2016, 30, 747–762. [CrossRef]

- Jamro, S.; Dars, G.H.; Ansari, K.; Krakauer, N.Y. Spatio-Temporal Variability of Drought in Pakistan Using Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9. [CrossRef]

- Haroon, M.A.; Zhang, J.; Yao, F. Drought Monitoring and Performance Evaluation of MODIS-Based Drought Severity Index ( DSI ). Nat. Hazards 2016, 84, 1349–1366. [CrossRef]

- Bibi, T.; Ahmad, M.; Bakhsh Tareen, R.; Mohammad Tareen, N.; Jabeen, R.; Rehman, S.U.; Sultana, S.; Zafar, M.; Yaseen, G. Ethnobotany of Medicinal Plants in District Mastung of Balochistan Province-Pakistan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 157, 79–89. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Shahab, S.; Fani, M.I.; Wahid, A.; Hassan, M.; Khan, A. Climate and Weather Condition of Balochistan Province Pakistan Climate and Weather Condition of Balochistan Province , Pakistan. Int. J. Econ. Environ. Geol. 2021, 12, 65–71.

- Khan, A.J.; Koch, M. Selecting and Downscaling a Set of Climate Models for Projecting Climatic Change for Impact Assessment in the Upper Indus Basin ( UIB ). 2018. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Gupta, A. Das; Babel, M.S. Spatial Disaggregation of Bias-Corrected GCM Precipitation for Improved Hydrologic Simulation: Ping River Basin, Thailand. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2007, 11, 1373–1390. [CrossRef]

- Mckee, T.B.; Doesken, N.J.; Kleist, J. The Relationship of Drought Frequency and Duration to Time Scales. 1993, 17–22.

- Adnan, S.; Ullah, K.; Shuanglin, L.; Gao, S.; Khan, A.H.; Mahmood, R. Comparison of Various Drought Indices to Monitor Drought Status in Pakistan. Clim. Dyn. 2018, 51, 1885–1899. [CrossRef]

- Turkes, M.; Tath, H. Use of the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) and a Modified SPI for Shaping the Drought Probabilities over Turkey. Int. J. Climatol. 2009, 29, 2270–2282. [CrossRef]

- Mann, H.B. NONPARAMETRIC TESTS AGAINST TREND1 By HENRY B. MANN. 2013, 13, 245–259.

- Golian, S.; Mazdiyasni, O.; Aghakouchak, A. Trends in Meteorological and Agricultural Droughts in Iran. 2015, 679–688. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Ren, G.; Yang, G.; Feng, Y. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology Analysis of the Spatiotemporal Variability of Droughts and the e Ff Ects of Drought on Potato Production in Northern China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2019, 264, 334–342. [CrossRef]

- Baig, M.R.I.; Shahfahad; Waseem Naikoo, M.; Ansari, A.H.; Ahmed, S.; Rehman, A. Spatio - Temporal Analysis of Precipitation Pattern and Trend Using Standardized Precipitation Index and Mann – Kendall Test in Coastal Andhra Pradesh. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2022, 8, 2733–2752. [CrossRef]

| Season | Topography | Duration |

|---|---|---|

| Winter | Hilly area | Seven months |

| Plain Area | Five months | |

| Summer | Hilly area | Five months |

| Plain Area | Seven months |

| S. No. |

Gauge Station |

Latitude (Degree) |

Longitude (Degree) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Zhob | 31.350 | 69.467 |

| 2 | Quetta | 30.083 | 66.967 |

| 3 | Barkhan | 29.883 | 69.717 |

| 4 | Kalat | 29.033 | 66.583 |

| 5 | Nokkundi | 28.817 | 62.750 |

| 6 | Dalbandin | 28.883 | 64.400 |

| 7 | Khuzdar | 27.833 | 66.633 |

| 8 | Panjgur | 26.967 | 64.100 |

| 9 | Lasbella | 26.233 | 66.167 |

| 10 | Turbat | 25.983 | 63.067 |

| 11 | Uthal | 25.817 | 66.617 |

| 12 | Gwadar | 25.133 | 62.333 |

| Historical | RCP 4.5 | RCP 8.5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-Value | Sen's Slope | p-Value | Sen's Slope | p-Value | Sen's Slope | ||

| Zhob | SPI | 0.51205 | -0.00012 | 0.68596 | -0.00005 | 0.48736 | -0.00008 |

| Duration | 0.58640 | 0.00000 | 0.24680 | 0.00000 | 0.06030 | -0.01060 | |

| Severity | 0.45130 | 0.00560 | 0.32490 | -0.00770 | 0.31870 | 0.00470 | |

| Intensity | 0.41940 | 0.00120 | 0.40520 | -0.00100 | 0.40520 | -0.00100 | |

| Peak | 0.33220 | 0.00280 | 0.29910 | -0.00210 | 0.74030 | 0.00060 | |

| Quetta | SPI | 0.14060 | -0.00028 | 0.47199 | -0.00008 | 0.98782 | 0.00000 |

| Duration | 0.98300 | 0.00000 | 0.66350 | 0.00000 | 0.69280 | 0.00000 | |

| Severity | 0.93330 | -0.00040 | 0.35130 | -0.00580 | 0.50740 | 0.00400 | |

| Intensity | 0.88910 | -0.00020 | 0.30700 | -0.00100 | 0.37670 | 0.00110 | |

| Peak | 0.93890 | -0.00020 | 0.46910 | -0.00110 | 0.44650 | 0.00160 | |

| Barkhan | SPI | 0.26518 | -0.00021 | 0.88722 | 0.00000 | 0.72998 | 0.00000 |

| Duration | 0.80180 | 0.00000 | 0.89470 | 0.00000 | 0.31360 | 0.00000 | |

| Severity | 0.75250 | 0.00150 | 0.99060 | 0.00000 | 0.25600 | 0.00240 | |

| Intensity | 0.34760 | 0.00120 | 0.69050 | -0.00030 | 0.40840 | 0.00050 | |

| Peak | 0.57160 | 0.00120 | 0.95490 | 0.00000 | 0.21530 | 0.00140 | |

| Kalat | SPI | 0.07669 | -0.00033 | 0.91634 | 0.00000 | 0.51402 | 0.00004 |

| Duration | 0.68240 | 0.00000 | 0.62070 | 0.00000 | 0.43800 | 0.00000 | |

| Severity | 0.95620 | 0.00060 | 0.97680 | 0.00000 | 0.65810 | 0.00140 | |

| Intensity | 0.92710 | 0.00020 | 0.53170 | -0.00040 | 0.95190 | 0.00010 | |

| Peak | 0.62130 | 0.00140 | 0.71970 | 0.00000 | 0.61490 | 0.00050 | |

| Noukkundi | SPI | 0.12863 | -0.00019 | 0.00841 | -0.00024 | 0.20181 | -0.00012 |

| Duration | 0.26790 | 0.00000 | 0.39780 | 0.00000 | 0.06090 | 0.00000 | |

| Severity | 0.33020 | -0.00540 | 0.41580 | -0.00280 | 0.56310 | 0.00150 | |

| Intensity | 0.59380 | -0.00040 | 0.31830 | -0.00080 | 0.29850 | -0.00080 | |

| Peak | 0.59670 | -0.00090 | 0.59670 | -0.00090 | 0.21980 | -0.00140 | |

| Dalbandin | SPI | 0.07734 | -0.00029 | 0.64722 | -0.00003 | 0.45909 | -0.00007 |

| Duration | 0.62460 | 0.00000 | 0.50990 | 0.00000 | 0.39460 | 0.00000 | |

| Severity | 0.67910 | 0.00220 | 0.57690 | -0.00250 | 0.39110 | -0.00480 | |

| Intensity | 0.99090 | 0.00000 | 0.07880 | -0.00170 | 0.41620 | -0.00100 | |

| Peak | 0.55380 | 0.00140 | 0.46720 | -0.00090 | 0.29700 | -0.00150 | |

| Khuzdar | SPI | 0.22427 | -0.00021 | 0.35833 | 0.00003 | 0.94483 | 0.00000 |

| Duration | 0.39940 | 0.00000 | 0.86800 | 0.00000 | 0.80450 | 0.00000 | |

| Severity | 0.90410 | -0.00070 | 0.71020 | 0.00073 | 0.79760 | -0.00051 | |

| Intensity | 0.66270 | 0.00070 | 0.58260 | 0.00040 | 0.80640 | -0.00020 | |

| Peak | 0.81920 | 0.00060 | 0.46260 | 0.00060 | 0.63810 | -0.00060 | |

| Panjgur | SPI | 0.36514 | -0.00016 | 0.19098 | -0.00011 | 0.94689 | 0.00000 |

| Duration | 0.73470 | 0.00000 | 0.22120 | 0.00000 | 0.40920 | 0.00000 | |

| Severity | 0.62540 | -0.00340 | 0.47800 | 0.00280 | 0.62000 | 0.00270 | |

| Intensity | 0.82250 | -0.00040 | 0.86200 | -0.00010 | 0.86560 | -0.00020 | |

| Peak | 0.98950 | 0.00010 | 0.83060 | 0.00000 | 0.94690 | 0.00000 | |

| Lasbella | SPI | 0.00319 | 0.00319 | 0.68805 | -0.00001 | 0.01517 | -0.00021 |

| Duration | 0.13500 | 0.00000 | 0.38010 | 0.00000 | 0.85660 | 0.00000 | |

| Severity | 0.08750 | -0.00840 | 0.75290 | 0.00060 | 0.90420 | 0.00000 | |

| Intensity | 0.12420 | -0.00150 | 0.26320 | -0.00050 | 0.70130 | 0.00010 | |

| Peak | 0.14880 | -0.00250 | 0.67560 | 0.00000 | 0.75570 | 0.00000 | |

| Turbat | SPI | 0.54739 | -0.00008 | 0.78605 | 0.00000 | 0.00005 | -0.00028 |

| Duration | 0.61780 | 0.00000 | 0.15460 | 0.00000 | 0.31060 | 0.00000 | |

| Severity | 0.86660 | -0.00170 | 0.37260 | 0.00080 | 0.15360 | -0.00140 | |

| Intensity | 0.19770 | -0.00120 | 0.87950 | 0.00000 | 0.28740 | -0.00040 | |

| Peak | 0.66430 | -0.00070 | 0.42610 | 0.00000 | 0.16480 | 0.00000 | |

| Uthal | SPI | 0.02714 | -0.00024 | 0.23098 | -0.00005 | 0.00015 | -0.00026 |

| Duration | 0.05550 | 0.01390 | 0.68760 | 0.00000 | 0.06230 | 0.00000 | |

| Severity | 0.02890 | -0.00720 | 0.58470 | 0.00010 | 0.06050 | -0.00490 | |

| Intensity | 0.12180 | -0.00130 | 0.67810 | 0.00000 | 0.15530 | -0.00090 | |

| Peak | 0.04450 | -0.00250 | 0.90000 | 0.00000 | 0.09320 | -0.00190 | |

| Gwadar | SPI | 0.48114 | -0.00009 | 0.40615 | -0.00006 | 0.00203 | -0.00027 |

| Duration | 0.78940 | 0.00000 | 0.45300 | 0.00000 | 0.49320 | 0.00000 | |

| Severity | 0.13920 | -0.00670 | 0.43640 | -0.00180 | 0.32250 | -0.00240 | |

| Intensity | 0.00860 | -0.00230 | 0.44210 | -0.00050 | 0.30140 | -0.00090 | |

| Peak | 0.01540 | -0.00360 | 0.58960 | -0.00030 | 0.14220 | -0.00180 | |

| Statistically Significant at 95% | |||||||

| Not Statistically Significant | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).