1. Introduction

The market of services provided by courier operators has recently experienced expanding growth. The main cause of the increase in volumes of goods delivered, especially in parcel shipments is e-commerce, an indispensable part of global retail. One of the most important factors of this phenomenon is the number of over five billion internet users worldwide. With the widespread availability of online shopping, retail e-commerce sales were estimated to exceed 5.7 trillion U.S. dollars globally in 2022. The forecasts indicate its further growth by 56 percent over the next years, reaching about 8.1 trillion dollars by 2026 [

1].

An increase of retail in e-commerce services brings new challenges especially in urban areas [

2] for the logistic sphere of how to deliver specific goods to the final consumers in the shortest possible time at reasonable costs. There are several different methods and approaches to the delivery of goods to the final retail recipient, depending on the specificity of the industry, type of goods and customer preferences creating different policies for online-to-offline (O2O) retailing strategy [

3,

4,

5] or even integrating online and physical stores through omnichannel (OC) distribution [

6]. The most popular ways of delivering goods to a retail customer are by: couriers, logistics service provider, e-commerce operators, pickup at the store: BOPIS (Buy Online, Pick-Up In-Store) or other PUDO (Pick Up Drop Off) point. Along with the last possibility of delivery, there are several options that give users the freedom and convenience to choose: point-to-point, point-to-door or door-to point. Such variety gives the opportunity to decide when and where the recipients want to send, return or collect parcels. This makes it possible to eliminate problems related to the delivery of goods to the retail customer, including those related to the collection and delivery to the point of sale of unwanted, advertised or incorrectly delivered goods to the final customer. in the issue of the last kilometer in the field of delivery of courier parcels, several methods of solving problems in terms of the possibility of their delivery have been proposed:

allowing access to the house or its element to the courier delivering the package, who places the package in an electronic terminal secured with a confirmation code,

leaving the package at the place of residence without the need to access the house, i.e., in the so-called home pickup box,

delivery of the package to the local agency, which in turn delivers the package to the customer’s home,

the use of pick-up points i.e., places where the customer can pick up the parcel on his own (they can be divided into self-service and those where the release of the parcel requires service by staff)

In each of these cases, it is essential to ensure efficient logistics, shipment tracking and communication with the customer to ensure satisfaction and timely delivery. It is important to provide support from local authorities and entrepreneurs in the aspects of spatial development in urbanized areas, where the availability of points (reception boxes, delivery boxes, controlled access system, collection points and locker-banks [

7]) is one of the parameters of developing smart cities and last mile delivery efficiency [

8]. Moreover, automated parcel lockers (APLs), mailboxes or automated parcel lockers are usually accessible 24/7, unless they are located, for example, in shopping malls, which have limited opening hours [

9]. Those automated lockers, parcel kiosks, locker boxes, self-service delivery lockers, and intelligent lockers are now categorized as self-service technologies (SSTs) for self-service collection and return of goods purchased online [

10]. For this reason, as predicted by industrial reports [

11], parcel lockers have received positive feedback from both consumers and businesses [

12,

13] and the demand for parcel locker hubs is booming, especially in Sweden, Germany, Great Britain, France, Belgium.

The largest US carrier offering this type of service today is the postal operator UPS with 82 locker service locations at select locations in various states in the UPS Store. In Europe, the Deutsche Post DHL Group introduced DHL Packstation in 2001 which now includes 11,500 locker stations working nationally for out-of-home (OOH) delivery. However, DHL Parcel operates in 28 European countries. The partnership between DHL and Cainiao is aimed as setting up a network of approximately 1,200 parcel lockers across Poland, one of the fastest growing e-commerce markets in Europe, with up to 40% of consumers preferring shipments delivered to parcel boxes. The largest network in Poland currently is InPost, with 20,000 automated parcel machines in Poland. There are almost as many of them as all ATMs in this country and four times more than all petrol stations [

14]. In addition to Poland, the company operates under its name in Great Britain with over 3,000 parcel lockers, Italy (around 300 devices) and plans to place 1,000 machines for the city of Salzburg in Austria. Parcel lockers of this company are used in the networks of local courier or postal companies in such countries as: United Arab Emirates, Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Colombia, Brazil and the Netherlands. The Polish network of parcel lockers is the largest infrastructure of this type in Europe. As a result, 59 % of Poles will find a parcel locker within a distance that can be covered in less than seven minutes on foot, which is in line with the 15-minute city (FMC) concept derived from smart cities. In urban areas, 85% of them have such or shorter distance to the parcel locker.

Currently, there are many types of parcel lockers available on the market, including: indoor lockers, outdoor lockers (surface-mounted, mounted on building facades, built-in, fence boards, free-standing), drop box lockers, refrigerated lockers, package room solutions or open locker networks and others. They can be individual/collective, public/private, electronic/mechanic or stationary/mobile [

15]. The devices are available in hundreds of colors, materials and sizes, according to the customer’s preferences. It is important that solutions for mounted parcel lockers meet the guidelines of PD CEN/TS 16819:2015 standard [

16] which describes the technical features of parcel boxes for end use. This covers technical features such as size of parcels, ergonomics and safety, corrosion and water penetration resistance and security of parcel delivery.

The traditional system of parcel lockers consists of 76 boxes, available in three sizes. Usually parcel lockers are designed in such a way that 32/35 parcels of big size (640x380x80 mm), 32/33 parcels of medium size (640/380/190 mm) and 12 parcels of small (640x380x410 mm) size can be deposited in them, up to 25 kg for a parcel. The system of automatic post office boxes used for sending and receiving parcels may, however, due to its modular structure, may have a different size, which should be adapted to the demand for services reported in a given area. Attention should be paid to the digitization of parcel locker service in smart cities, which enables contactless service using a special application on the user’s smartphone. It turned out to be very convenient especially during the pandemic.

Picking up a parcel at a parcel locker is convenient, especially for people who prefer flexibility and independence in terms of picking up the goods. Parcel lockers are usually available whole day, which allows to collect the parcel at a time convenient for the customer. The time slot of the delivery is one of the elements which was investigated as crucial in decision-making of online consumer behavior [

17,

18,

19]. The other factors indicated are speed of the delivery [

20], timeliness [

21], consumer preferences for delivery attributes in online retailing [

22,

23] and of course delivery fees [

24]. The price for the delivery service is one of the most important factors determining the need to develop a system of low-cost parcel machines in rural areas. The investigations on the willingness to pay for different delivery options show that 70% consumers are content with the cheapest form of home delivery and 23% would pay more for same-day delivery [

25]. Many scientists make research in order to classify factors influencing online purchase intention towards online shopping [

26,

27,

28], however, the economic practice shows that they are primarily: fast delivery (59%), secure tracking (49%), secure packaging (36%), sustainable packaging (26%), flexible delivery (23%) and sustainable delivery route (12%) [

29].

Ultimately, the decision to use specialized devices for courier parcel delivery and collection should be based on a comprehensive analysis of these factors, considering the specific requirements and goals of the courier service provider. Regardless, the main factors that must be considered are those related to their advantages in relation to the quality of customer service, namely: proximity to infrastructure, ease of use, speed, price attractiveness, security and continuity of service.

To address practical issues and fill a research gap, a customer perspective was adopted in the manuscript to explore and provide insight into consumer perceptions of parcel lockers and customer satisfaction with their service. This paper aims to answer the following main research questions: (1) What are the performance and service quality attitudes for parcel distribution using parcel lockers? and (2) which of them are most important from the user’s perspective? Using the example of Polish e-consumers, the study determines which quality features of the customer service process can be classified according to the Kano model groups. The findings provide classification of must-be, one-dimentional, indifferent and attractive features of the customer service process enable stakeholders to make rational decisions related to the development of automated parcel lockers networks in cities. This paper also contributes to the literature by filling the gap in our knowledge of customer satisfaction in relation to this widely applied self-service technology.

The study is organized as follows:

Section 2 includes a brief scientific literature review of customer attitude and satisfaction with parcel lockers, the methods used to analyze them and the most important research achievements in this area.

Section 3 describes the research method based on Kano model, and

Section 4 presents its. This is followed by a discussion in

Section 5 and conclusions in

Section 6.

2. Scientific Literature Review

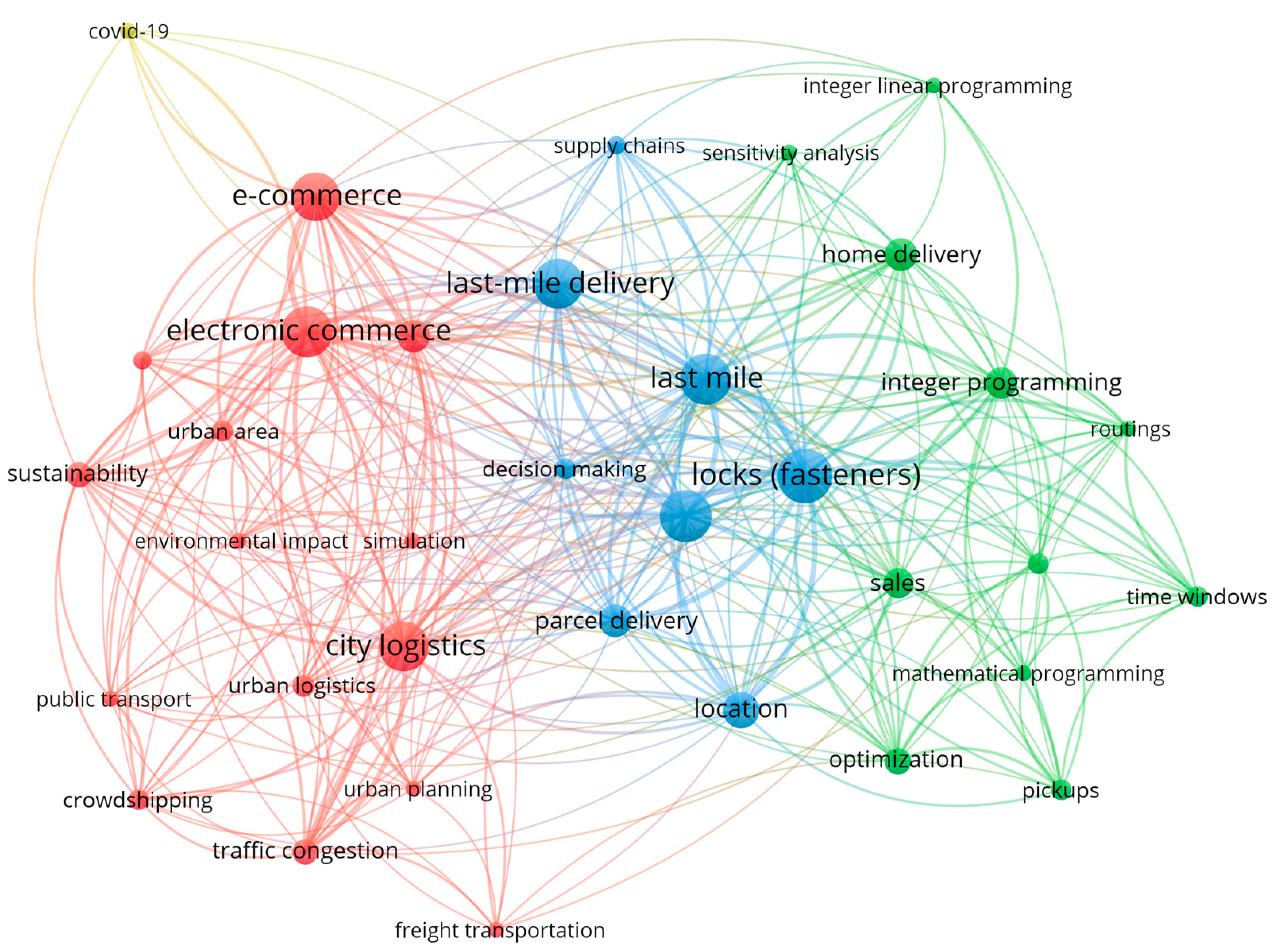

The analysis of the literature in the researched area was based on the resources of the Web of Science and Scopus databases. Searching the databases in the keywords “parcel locker(s)” allowed to extract only 156 documents from 2014 until 2023, mainly articles (100), conference papers (44), book chapters (8) and other. The authors of the publication are mainly scientists from those countries where the technology of courier parcels distribution using automatic boxes is the most popular: Italy (23), China (20), United States (14), Poland (13), Germany (12), Australia (9), United Kingdom (9), Netherlands (8) and other. Co-occurrence analysis of all 1103 key words from the database allowed to construct and visualize bibliometric networks of 35 common keywords with VOSviewer software tool presented in

Figure 1.

The bibliometric network visualization of the keywords allowed to identify four clusters related to parcel lockers. Cluster 1 refers to 15 items associated with city logistics, e-commerce, sustainability, urban area, urban planning etc. Cluster 2 with 11 items relates to sales, home delivery, pickups and optimization methods (vehicle routing problem, time windows, integer linear programming, sensitivity analysis). Cluster 3 applies to 8 items of decision making, location, parcel delivery, last mile delivery and supply chains. The last Cluster 4 refers to the latest to the recently revealed factor related to the outbreak of the covid-19 pandemic, which effectively contributed to the development of the technology of automatic collection of courier parcels. This analysis shows that there is a research lack in area of customer approach on parcel lockers users. However, some of the subject areas are identical to the qualitative characteristics perceived as satisfactory by the recipients of parcel locker services.

When analyzing the literature related to the quality of service, attention should be paid to those publications that primarily concern research on the attitude of consumers to the use of automated parcel lockers and related self-service technologies. Chen et al. [

30] enhanced understanding of the components and processes that are involved in

consumer intentions and consumer participation readiness (CPR) to use automated parcel stations (APS).

One of the driving factors is technology anxiety understood as the ability and willingness of customers to use of self-service technologies (SSTs) as underlined by Meuter et al. [

31] and Vo. et al. [

32]. However, studies of Gelderman et al. [

33] have shown that an even more dominant effect on the use of SSTs is the need for interaction. Moreover, as investigated by Alloulbi et al. [

34] technology anxiety was found to be a significant and negative determinant of decision-making in smart cities. In the results of Yuen et al. [

35] research five key characteristics of innovation, relative advantage, compatibility and trialability positively influence customers’ intention to use self-collection services can be shown. Similar results are presented in Neto and Vieira [

36] publication. And in [

37] effects of convenience, privacy security, and reliability are defined as determinants of customers’ intention to use smart lockers for last-mile deliveries. Service convenience expressed in specific variables like network density, parking availability, spatial location, proximity to consumers’ home or office, safe and secure operation, hours of operation are revealed by Kedia et al. [

38] and spatial accessibility revealed by Schaefer et al. [

39] as obligatory in the acceptability of new delivery technologies from consumers’ perspective. Tsai and Tiwasing [

40] results revealed that convenience, reliability, privacy security, compatibility, relative advantage, complexity, perceived behavioral control, and attitude influence consumers’ intention to use smart lockers in last mile delivery [

41].

Lee and Lyu [

42] examined

personal values and

consumer traits as antecedents of attitudes toward an intention of using SSTs as the need for interaction and self-efficacy. According to Milioti et al. [

43] consumer characteristics, like environmental awareness, can be an effective subject of consideration in modelling consumers’ acceptance for the click and collect service. Understanding

consumer preferences in relation to selected attributes of deliveries, such as location, delivery time, information and traceability, and cost of transportation, and the willingness to use automatic delivery stations are, according to [

44], factors necessary to estimate the demand for new technologies in urban areas. According to Rai et al. [

45], APS solutions are growing in popularity also because consumers choose them due to previous disappointment resulting from failed delivery problems observed in the urban distribution of goods.

The above research on the key factors related to consumer intentions, traits and preferences influencing the choice of APS technology was carried out through statistical analysis of survey studies in various parts of the world. However, Lai et al. [

46] introduced service quality (SERVQUAL) model and logistics service quality (LSQ) model, this study investigates the antecedents of customer satisfaction with parcel locker services in last-mile logistics. The analysis of the scientific literature led to the conclusion that no earlier publications using the Kano model for analysis in the selected area were found.

Understanding consumer attitude influencing the choice of APS technology in last mile delivery has a direct or indirect impact on the customer satisfaction with the service provided. Except that, customer loyalty, customer retention, and profitability are elements of firm operations, which in turn are related to service quality as agreed by Gupta [

47] and Li and Shang [

48]. Although extant studies have argued that consumer intentions and preferences clearly impact parcel lockers as self-collection service, scant evidence has been provided on the influencing factors of customer satisfaction regarding parcel lockers service quality. Thus, the scientific objective of this study is to identify and range quality attributes of automated parcel lockers services in urban areas to fill the gap of knowledge in this area.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research framework

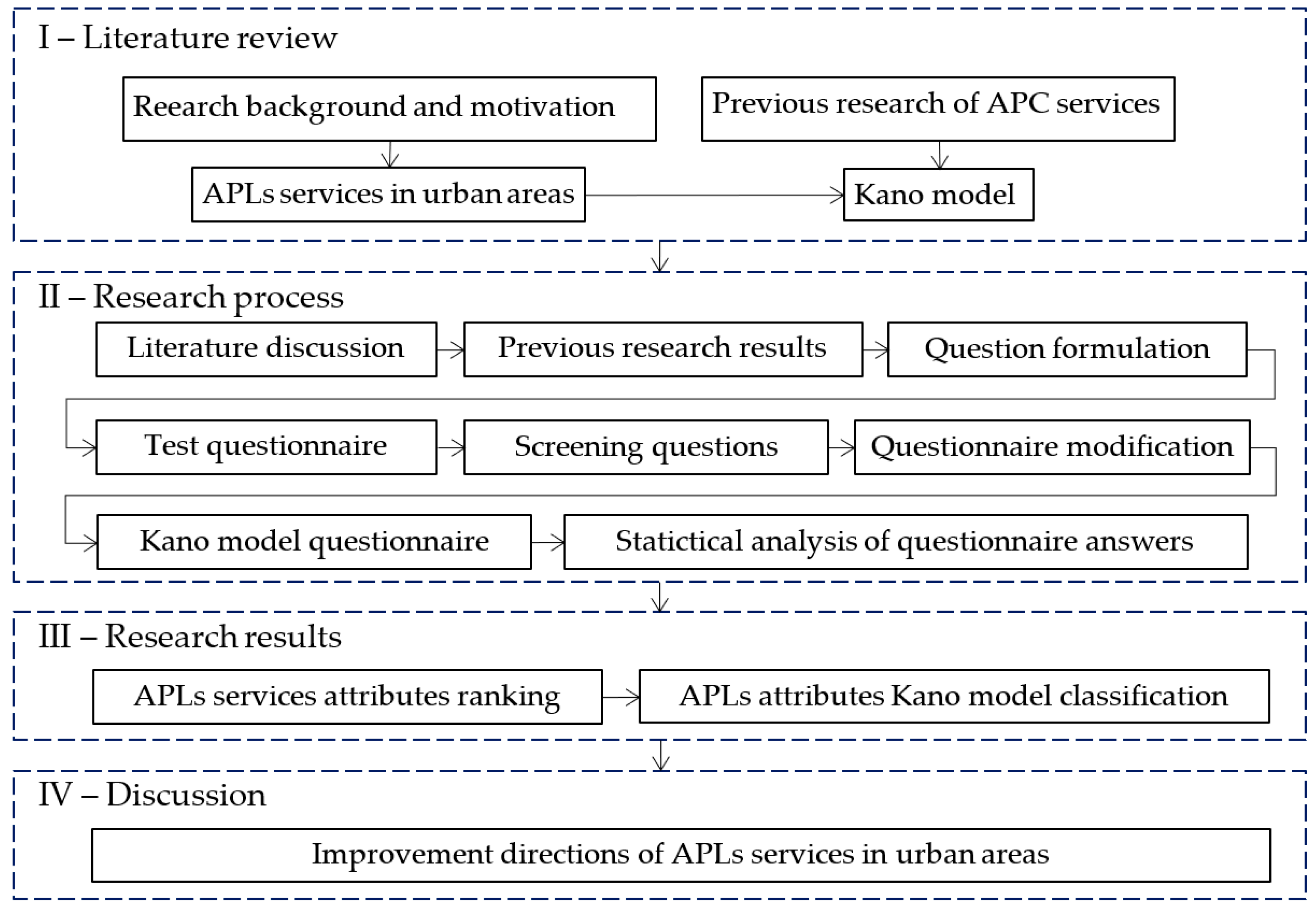

The research part of the paper is focused on the analysis of APC services in urban areas from the point of view of their users. Information on the hierarchy of customer expectations towards parcel machines may be helpful in improving services in the field of deliveries with their use, but also in spatial planning or making decisions regarding the development of this type of infrastructure in cities. The research framework includes four stages presented with a diagram in

Figure 2.

Stage I was the initial stage focused on the review. As a result, the assumptions and objectives of automated parcel lockers services attributes analysis were developed. This part was implemented in two tracks. First one was the scientific literature review the most important research achievements of customer attitude and satisfaction with parcel lockers and the methods used to analyze them. In the second path, the achievements of previous analyzes were used. The joint results of this part of the methodology enabled the decision to use the Kano model, which has never been used before to classify APLs services attitudes.

Stage II was focused on the research process where the procedure was carried out according to the Kano model. Based on the knowledge related to the literature review and previous university research results [

49,

50,

51,

52,

53], preliminary questions were developed for the survey on the needs and expectations of users of parcel machines systems in cities. In the next part of the research, a questionnaire test was carried out, which allowed to check the respondents’ understanding of the questions. After the tests, it was decided to modify the survey layout for a more transparent reception of questions. Then, a survey was carried out in accordance with the Kano model, followed by a statistical analysis of the obtained results. Conducting the Kano questionnaire concerned twenty-one features of the customer service quality process using parcel machines. Due to the automation of the process of collecting and sending parcels and the use of a dedicated mobile application, the online survey with Google Forms was also used for the research. The survey form in question consisted of 24 closed, single-choice questions. The survey was conducted at the turn of November and December 2022. 468 respondents took part in the survey, of which 55.6% were women, which corresponds to the total number of 260 people surveyed. Out of 468 people participating in the study, as much as 65% (304 people) were people aged 18-24. The second largest group in terms of share, constituting 23.1%, are people aged 25-34 (108 people). Another 3.4% of all respondents were in the age range of 35-44 (16 people), while 4.3% were in the age range of 45-54 (20 people). Twenty people under the age of 18 correspond to 4.3% of all respondents.

Stage III of the methodology was concentrated on result analysis. According to the questionnaire survey results, a Kano model was established to obtain the satisfaction ranking of automated parcel lockers services’ attributes

Finally, stage IV covered the discussion on the results. Further conclusions related to the development and possible improvements for APLs in urban areas were made.

3.2. Kano model

Due to its popularity, accessibility and transparency, the Kano model was chosen as the optimal method for analysis and classification of the most important attributes of the courier services quality, including the delivery of parcels through automated sending and receiving parcel lockers. It is based on posing logical and unambiguous questions that allow to determine the group for which a given distribution process is dedicated.

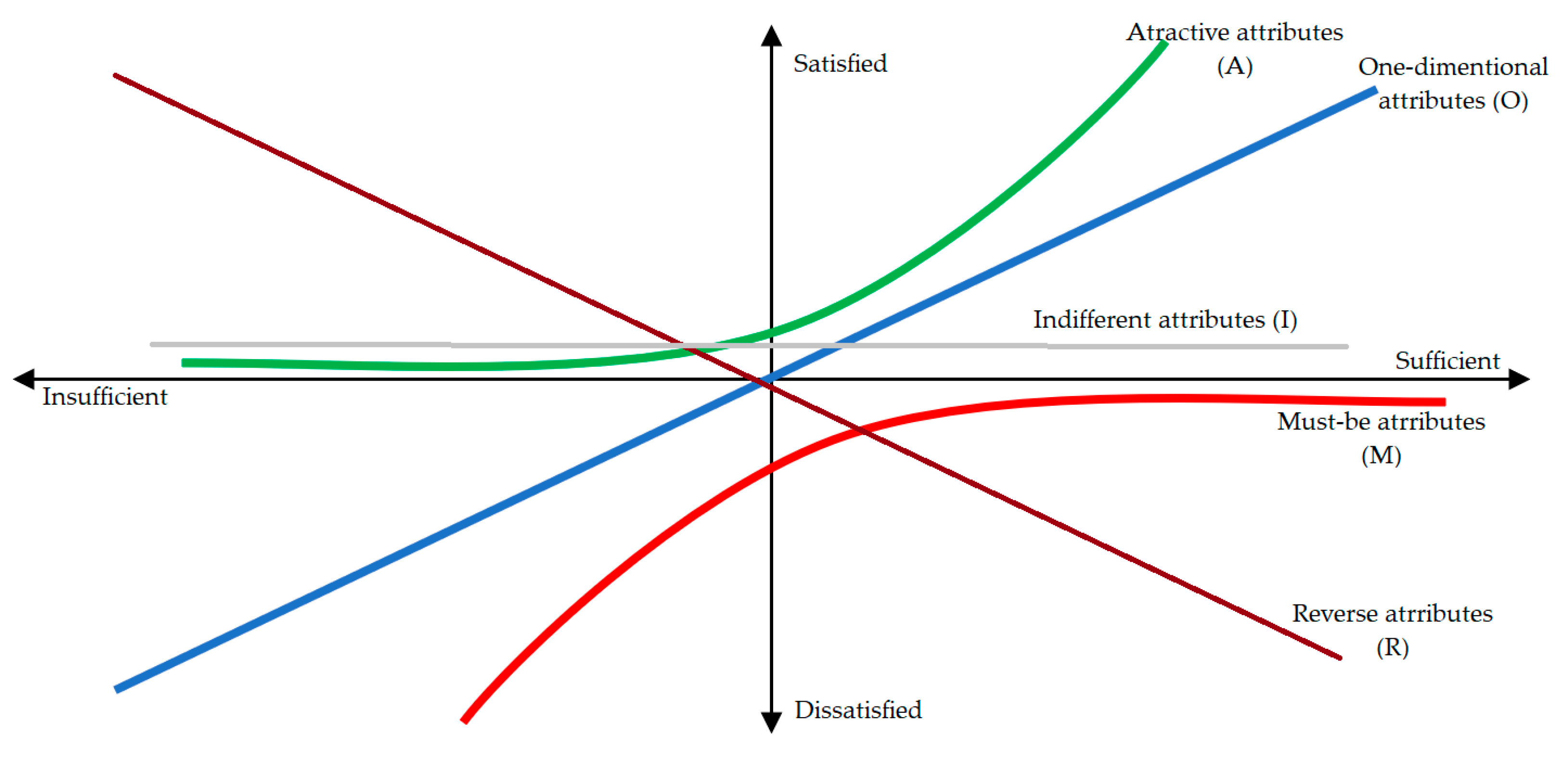

Kano model is a two-dimensional modeling tool (satisfaction/sufficiency – see

Figure 3) proposed by Noriaki Kano of Tokyo Institute of Technology [

54], mainly used for user requirements classification and prioritization classes. The use of the Kano system is practically reflected in the modeling of many processes, including services and objects. The analysis was supported with review papers of the most commonly used approaches to the classification of quality attributes according to the Kano model published by Berger et al. [

55], Wang and Ji [

56], Mikulić and Prebežac [

57], Wittel et al. [

58] or Kermanshachi et al. [

59].

The Kano model has been previously successfully used as a technique for classifying quality attributes in a whole range of research areas, like: hospitality services by Zobnina and Rozkhov [

60], healthcare industry by Gupta and Srivastava [

61], restaurant services by Pai et al. [

62] and Chen et al. [

63], elderly care service platform by Zhou et al. [

64] or even hotel service robots by Xie et al. [

65].

The main assumption of the Kano model is that not all attributes of the object or service are equally important to the customer. Three basic groups of features should be distinguished in the Kano model:

Must-be attributes (M). It is a set of requirements that the recipient is not aware of, but they are extremely important from the perspective of shaping his satisfaction or dissatisfaction. This group is characterized by requirements whose fulfillment will not increase customer satisfaction, but their absence will result in customer dissatisfaction;

One-dimensional attributes (O). This is a group of desired customer requirements. This means that their implementation increases satisfaction, but failure to meet these requirements will result in dissatisfaction;

Attractive attributes (A). These are the service requirements to attract attention. Their fulfillment has a huge effect on the increase in satisfaction, while their failure will affect the customer’s feelings.

In addition to the above-mentioned basic groups of features, Kano also defined the so-called additional requirements that are more difficult to identify due to their specificity. These include:

Indifferent attributes (I). The presence or absence of these requirements will in no way affect the return or reduction of customer satisfaction. They are irrelevant;

Questionable attributes (Q). This is a group of requirements about which there is no reliable information on whether they are relevant to the consumer;

Reverse attributes (R). They appear when the opposite of a given feature is important to the client.

According to the refined theory of the Kano model presented by Lo [

67], a product or service pays more attention to whether the must-be quality, one-dimensional quality, and attractive quality are satisfied or not. Various classification methods were previously proposed with the cross-reference of the consumer’s options. Schvaneveldt et al. [

68], as well as Matzler and Hinterhuber proposed the five-grade evaluation. The last, verified methodological approach has been adapted to this study. According to the Kano model, each question is asked in two variants for the examined attitude as presented in

Table 1. In the positive variant, a question is built describing that something occurs, works, is sufficient. On the other hand, in the negative variant, the problem is that something is absent, does not work, is inefficient.

Based on the number of responses received within one feature, individual categories (A, M, O, R, Q or I) are determined, as presented in

Table 2. It is important to eliminate potential interference resulting from incorrectly formulated questions and their poor understanding by the respondents. To do this, the following two rules must be followed:

– if (A+M+O) > (R+Q+I), then finally the category from the group A, M, O with the highest value is selected;

– if (A+M+O) < (R+Q+I), then finally the category from the R, Q, I group with the highest value is selected.

To better understand the attitude of the APLs users it is important to acknowledge all the responses when evaluating and categorizing each factor. For this reason, Shahin et al. [

70] revised satisfaction coefficient (

) and dissatisfaction coefficient (

) used in the Kano model and advised to use the following ones:

Larger satisfaction coefficient indicates higher consumer satisfaction, while a smaller dissatisfaction coefficient means higher dissatisfaction. The difference between the satisfaction and dissatisfaction coefficients values is known as the total satisfaction index, and the attributes can be ranked, based on that calculated total value.

4. Results

Kano questionnaire concerned following twenty-one features of the customer service quality process using parcel machines:

24/7 customer support;

additional parcel locker services (e.g., refrigerated lockers, laundry services);

adjusting the size of package to the size of the box (parameter related to problems with removing the parcel when the parcel tightly fills the box);

advertisement on parcel locker;

convenience of receiving and sending parcels;

dedicated application;

ease of use of the parcel locker;

improvements for people with disabilities;

methods of the parcel pick-up (standard or automatically via smartphone);

methods of the parcel drop-off (standard or online without the need to print the shipping label, which is attached by the courier upon receipt);

natural environment awareness;

parcel locker location (related not only to a satisfactory distance, but also to the place, for example close to work or school);

parcel locker novelty (parameter related to modernity, because the newly created APLs sometimes differ from the previous ones);

parcel locker service time (time needed for parcel pick-up or drop-off);

parking next to the parcel locker;

placing the parcel in a specific box (the service is called: easy access zone and enables placing parcels in the lower compartments in the parcel locker);

possibility of using a multi-locker (allows to pick-up multiple parcels from multiple senders by one receiver or drop-off multiple parcels to one receiver);

security of the parcel placed in the locker;

size of the parcel locker (number of boxes);

temperature inside;

time window for parcel pick-up.

Table 3 presents the proportion questionnaire answers of each type of quality attribute to Kano groups and then the classification decision.

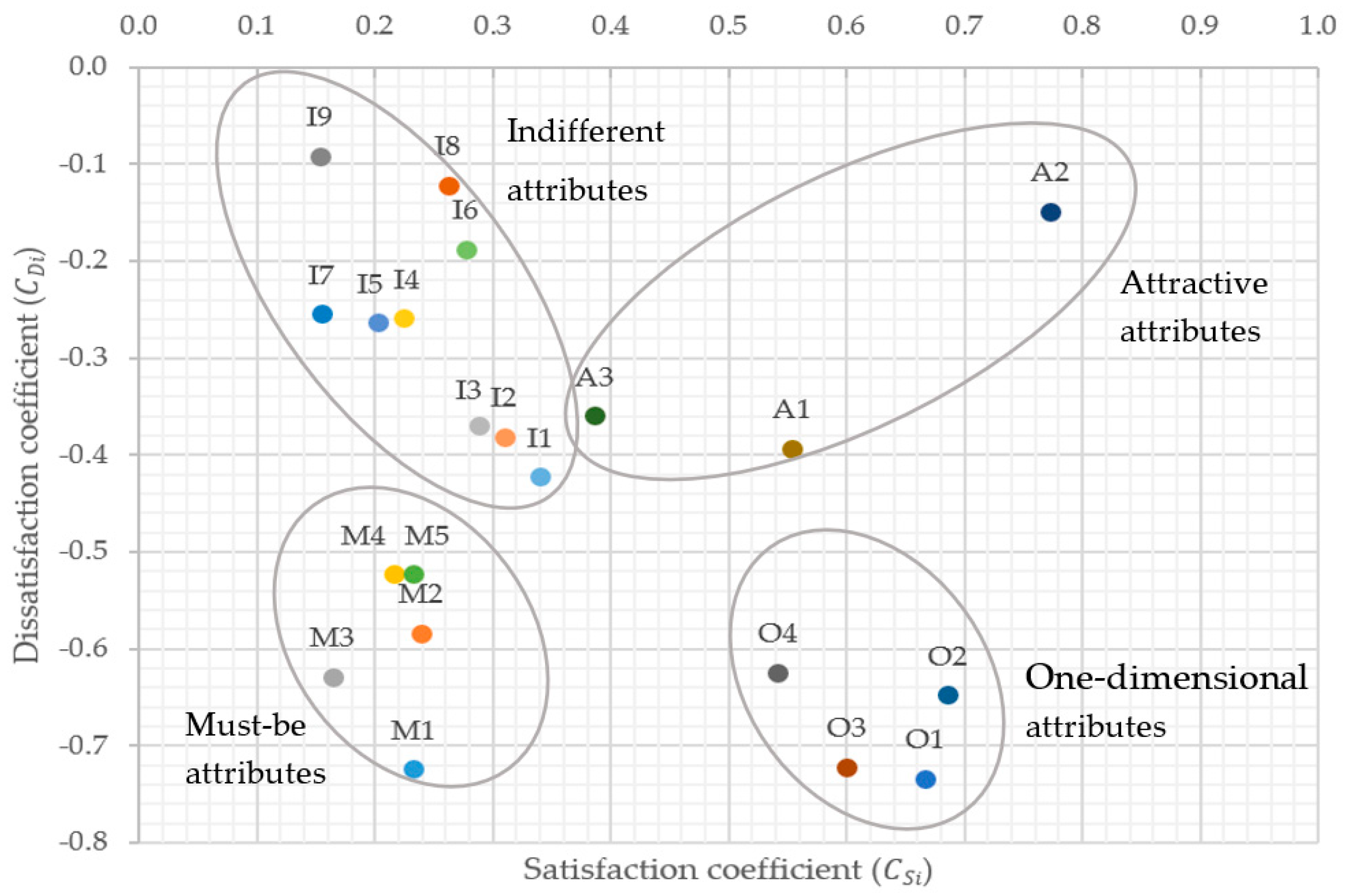

Based on the results of the respondents related to the Kano questionnaire, it was possible to classify 5 attributes to must-be (M) type, 4 attributes to one-dimensional (O) type, 3 attributes to attractive (A) type and 9 attributes to indifferent (I) type. When analyzing the percentage distribution of responses, no attitudes were assigned to the questionable (Q) nor reverse (R) types.

Must-be attributes are the ones that must be provided for the APLs users. Service providers need to regard this quality pattern when developing delivery services with parcel lockers usage. Dedicated application, possibility of placing the parcel in a specific box also for people with disabilities are extremely important issues for consumers. Also, analyzing locations of parcel locker stations in the city is crucial. Training of couriers in the selection of a specific box in a parcel locker when placing a parcel has a significant impact, according to respondents, on the ease of pick-up, and thus on the quality of service.

The one-dimensional attributes indicate the adequacy of quality for consumer satisfaction. They are used as a basis for APLs service providers to differentiate prices. The customers consider the basic functionality of parcel lockers to be important, which suggests that operators must maintain and improve the one-dimensional quality attributes of additional services offered, ensuring parcel safety or providing parking places next to automated parcel stations.

The attractive attribute is used as a tool to understand service differentiation and reflects a consumer’s desire for a specific feature. The result of this study revealed that consumers were not satisfied with, but accepted features related to operation time and convenience of use and possibility of parcel pick-up with different methods.

The indifferent attributes have a little effect on customer satisfaction. According to the research results, this was the biggest group of features related to advertisements put on APLs, possibility of using a multi-locker, 24/7 customer support, temperature inside or time window for parcel pick-up.

The consumer satisfaction coefficient (

) and dissatisfaction coefficient (

) were used to evaluate the degree of the customers’ satisfaction and dissatisfaction with the APLs services’ attributes. The total satisfaction calculation allowed to present the ranking of attributes according to their classification types in

Table 4. As in Xu et al. [

71] research, the matrix presented in

Figure 4 illustrates these relationships.

5. Discussion

The research carried out using the Kano methodology allowed to obtain answers to the research questions related to the attributes of servicing parcel lockers important for users and enabled their classification.

The most important factor necessary to maintain the high quality of services related to parcel lockers is a

dedicated application for their service. The most common in Poland, InPost Mobile application was created to improve the convenience of customers and expand the possibilities of managing their shipments. The application is free, available for download in the Google Play Store, Apple App Store and Huawei AppGallery. Since its introduction in 2019, the application has gained several improvements and useful features, such as: possibility of parcel tracking, remote opening of the parcel box (this service was the preferred form of service, especially during the covid-19 pandemic), possibility of shipping parcel without a printed label, notifications about packages ready for pick-up, possibility of extending the pick-up time, Easy Access Zone, dynamic redirection, quick returns, sharing parcel information between application users, cashless payment for cash on delivery (COD) parcels and map of Inpost APLs and navigation to the specified parcel locker. Mobile applications are indispensable, because, as Tang et al. [

72] emphasize adoption of Internet of Things (IoT) based smart parcel lockers has developed very rapidly. Niederprüm and van Lienden [

73] underline that operators have found innovative solutions for last mile delivery to improve access and operability, including the use of advanced technologies through the use of mobile applications, e.g., integrating electronic systems and wireless transfer of information between online retailers, deliverers and recipients, as well as enabling contactless parcel pick-up. Similarly, Akdoğan and Özceylan [

74] note that parcel locker applications can meet some of the alternative needs for environmentally friendly and efficient solutions for logistics services in harmony with the digitalizing world to enable

ease of use of APLs (the one-dimensional attitude.

The next must-be attitudes of parcel locker services are of technical nature. Feature connected with

adjusting the size of package to the size of the box it is certainly related to the negative experience of recipients with their parcel getting stuck in a locker or problems with its removal. Parcel locker stations (terminals) are constructed in different sizes in terms of the number of lockers they contain, ranging from compact terminals consisting of less than 15 lockers to large terminals that may contain more than 500 lockers (the largest parcel locker station in Europe is in Finland with 1,002 lockers [

73]). Parcel locker modules, adapted to parcels of various sizes, are configured to contain compartments of various sizes, adjusted to three standard dimensions: small, medium and large compartments. Typical locker dimensions can range from 8-75 cm x 35-40 cm x 60-64 cm depending on the supplier, and the configuration of the modules can generally be customized to include a certain number of specific cabinet sizes within the overall dimensions of the module. This is one of the factors influencing the multi-objective green express cabinet assignment problem in urban last-mile logistics presented by Ji et al. [

75]. Incorrectly matching the dimensions can lead to several problems, because the package will not fit into a too small locker. Parcel lockers are adapted to individual shipments, which is why it is important to provide clear information to users to avoid later problems. It is also good to give users brief instructions what to do when the chosen parcel locker size is too small for a drop-off service. Stojanov [

76] emphasizes that one of the limitations of parcel lockers is that not all parcels fit within the specified dimensions of each APL, and therefore would require alternative delivery methods.

The issue of

placing the parcel in a specific box relates to the Easy Access Zone service allows for the delivery of parcels to the lower-placed lockers at a height between 30 cm and 150 cm. This attitude of service is dedicated for users of short stature or for people with physical disabilities. According to the research results,

improvements for people with disabilities or special needs must also be considered by parcel lockers operators. As noted by Lagorio and Pinto [

77], any inconvenience or barriers arising in the service process can be easily overcome by providing a telephone customer service connected to the lockers and the inclusion of voice/commands for people with disabilities.

In view of the emergence of various operators operating parcel machines, it is worth looking at the one-dimensional attitudes of their services, which were indicated by the respondents, because they can contribute to gaining a competitive advantage. The first reported factor is

additional APLs services. Such ideas concerned, for example, the introduction of the Hi’Shine clothes dry cleaning service in Inpost parcel machines, but they were withdrawn from the market. Another is to enable the delivery of shipments at a controlled temperature. Wróbel-Jędrzewska and Polak [

78] propose construction of a prototype device (food parcel locker), consisting of small cooling and freezing boxes ensuring temperature conditions (+5°C or −18°C) to enable grocery storage.

Another attitude,

security of the parcel placed in APL is widely discussed by researchers. For example, the study of An et al. [

79] examines consumers’ decision to select parcel locker service regarding technology assessment and privacy protection concerns. The work of Min-Hye et al. [

80] suggests a double-security smart parcel locker to keep parcel safe from the risk of loss and personal information leakage by using parcel invoice bar-codes through near field communication (NFC) module for smart-phones. However, most recipients, as stated by Keen et al. [

81], perceive the perceived level of security of parcel locker service as satisfactory.

The next suggestion of

parking next to APL is related to the widely analyzed issue of the location of parcel lockers. When choosing locker installation place, Guerrero-Lorente et al. [

82] suggest that high demand points should be considered to obtain higher efficiency, such as: subway or bus stops, shopping centers, supermarkets etc. Iyer et al. [

83] noticed that for high density urban areas the optimal walking distance can vary widely across the network and the solution can deliver varying levels of benefit depending on the location of parcel lockers. For this reason, the possibility of parking at the parcel locker, according to Lachapelle et al. [

84], may be a decisive variable for this form of parcel delivery. As demonstrated by Wang et al. [

85] movable locker units with few lockers can be a more suitable for scattered low demand areas. Also, the approach of Schwerdfeger and Boysen [

86], as well as Lazarević et al. [

87] prove that mobile parcel locker (MPL) allow for easy access to hard-to-reach destinations and especially when driving autonomously, reduce customer inconvenience connected with walking or car parking.

The results of the study on indifferent attributes which have a little effect on customer satisfaction are surprising. It turns out that many of them are the subject of research by scientists and may in the future become factors of greater importance for users of parcel machines.

6. Conclusions

The main reason for the increase in the volume of shipments recorded by courier operators, visible especially in parcel shipments, is global electronic commerce, creating new trends in delivering goods purchased online to customers. An increase of retail in e-commerce services brings new challenges especially in urban areas for the logistic sphere of different delivery possibilities, in the shortest possible time and at reasonable costs. In view of new organizational and infrastructural solutions regarding the use of automated parcel machines in the distribution of goods, the issue of the quality of services and the needs of users becomes important.

To fill a knowledge gap, a customer perspective was adopted in the paper to explore and provide insight into consumer perceptions of parcel lockers and features of customer satisfaction with their service. Thus, the scientific objective of this study was to identify and range quality attributes of automated parcel lockers services in urban areas. The methodology based on the Kano model was adopted for the analysis, which has proven itself as a research method in studies on a different subject. The questionnaire, which is a research tool, included twenty-one attributes related to the quality of parcel locker services and was conducted on 468 respondents.

Based on the Kano questionnaire results, it was possible to classify 5 attributes to must-be (M) type, 4 attributes to one-dimensional (O) type, 3 attributes to attractive (A) type and 9 attributes to indifferent (I) type. It was also possible to classify the rankings of attributes in the groups basing on satisfaction and dissatisfaction coefficients. The must-be attributes which should become mandatory for service providers are according to users: parcel stations, ensuring improvements for the disabled, adjusting the size of the parcel to the size of the box, proper placement of the parcel in the box and a properly functioning dedicated application. This is confirmed by numerous studies of scientists cited in the work. It is also worth paying attention to one-dimensional attributes that can attract users such as: additional services, security issues of the parcels in lockers, parking zones provided nest to parcel stations and ease of use of APLs. The other attractive and indifferent should not be underestimated, because they become a very important carrier of information for decision makers related to spatial development of cities and entrepreneurs providing services related to the distribution of parcels.

A limitation of this study is that it is based on a convenience sample. Although a large sample of 468 respondents was carried out and all interest groups were well represented, older people were underrepresented in the research sample. While the possibility cannot be ruled out that this under-representation may have influenced the results to some extent, the fact that, also when shopping online, young users also dominate the statistics. Therefore, it may be advisable to repeat this study on a larger and more representative sample. Repeating the research in this direction would also be rational due to the fact that with the passage of time, other factors of the environment may change, influencing the decision-making of parcel machines users, and in particular the perception of quality attributes. Interesting results may also be presented when analyzing customer attitudes in cities in different countries, when their decisions are influenced by other cultural, religious, beliefs, etc. factors.

Further research work on the subject matter may concern the development of a decision-making model covering subsequent areas of parcel lockers services quality attributes. An interesting extension would be the analysis and verification of the comprehensiveness of these services, the range and flexibility of which are very diverse.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Author would like to thank the reviewers for their profound and valuable comments, which have contributed to enhancing the standard of the paper, as well as future research in this area.

Conflicts of Interest

Author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| APLs |

automated parcel lockers |

| APS |

automated parcel stations |

| BOPIL®

|

Buy Online, Pick-up in Locker |

| BOPIS |

Buy Online, Pick-Up In-Store |

| COD |

cash on delivery |

| CPR |

consumer participation readiness |

| FMC |

15-minute city |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| MPL |

mobile parcel locker |

| NFC |

near field communication |

| O2O |

online-to-offline |

| OC |

omnichannel |

| OOH |

out-of-home |

| PUDO |

Pick Up Drop Off |

| SSTs |

Self-Service Technologies |

References

- Chevalier, S.; Global retail e-commerce sales worldwide from 2014 to 2026. Statista 2022, eMarketer, Jul. 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/379046/worldwide-retail-e-commerce-sales/ (accessed 30 June 2023).

- Allen, J., Piecyk, M., Piotrowska, M., McLeod, F., Cherrett, T., Ghali, K., ... & Austwick, M. Understanding the impact of e-commerce on last-mile light goods vehicle activity in urban areas: The case of London. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2018, 61, pp. 325-338. [CrossRef]

- Dey, B. K., Sarkar, M., Chaudhuri, K., & Sarkar, B. Do you think that the home delivery is good for retailing?. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2023, 72, 103237. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, B., Dey, B. K., Sarkar, M., & AlArjani, A. A sustainable online-to-offline (O2O) retailing strategy for a supply chain management under controllable lead time and variable demand. Sustainability 2021, 13(4), 1756. [CrossRef]

- Choi, S. B., Dey, B. K., & Sarkar, B. Retailing and servicing strategies for an imperfect production with variable lead time and backorder under online-to-offline environment. Journal of Industrial and Management Optimization 2023, 19(7), pp. 4804-4843. [CrossRef]

- Hübner, A., Holzapfel, A., & Kuhn, H. Distribution systems in omni-channel retailing. Business Research 2016, 9, pp. 255-296. [CrossRef]

- Allen, J., Thorne, G., & Browne, M. BESTUFS good practice guide on urban freight transport. 2007. Available online: https://www.eltis.org/sites/default/files/trainingmaterials/english_bestufs_guide.pdf (accessed 30 June 2023).

- Iwan, S., Kijewska, K., & Lemke, J. Analysis of parcel lockers’ efficiency as the last mile delivery solution–the results of the research in Poland. Transportation Research Procedia 2016, 12, pp. 644-655. [CrossRef]

- Koncová, D., Kremeňová, I., & Fabuš, J. Last Mile and its Latest Changes in Express, Courier and Postal Services Bound to E-commerce. Transport and Communications 2022, 12, pp. 12-17. [CrossRef]

- Vakulenko, Y., Hellström, D., & Hjort, K. What’s in the parcel locker? Exploring customer value in e-commerce last mile delivery. Journal of Business Research 2018, 88, 421-427. [CrossRef]

- IPC. Annual Review 2020 Supporting posts during the COVID-19 crisis. Available online: https://www.ipc.be/sector-data/reports-library/ipc-reports-brochures/annual-review2020 (accessed 30 June 2023).

- Ducret, R. Parcel deliveries and urban logistics: Changes and challenges in the courier express and parcel sector in Europe — The French case. Research in Transportation Business & Management 2014, 11, pp. 15-22. [CrossRef]

- Morganti, E., Seidel, S., Blanquart, C., Dablanc, L., & Lenz, B. The impact of e-commerce on final deliveries: alternative parcel delivery services in France and Germany. Transportation Research Procedia 2014, 4, pp. 178-190. [CrossRef]

- InPost. Our history. Available online: https://inpost.eu/who-we-are/our-history (accessed 30 June 2023).

- Zurel, Ö., Van Hoyweghen, L., Braes, S., & Seghers, A. Parcel lockers, an answer to the pressure on the last mile delivery? New business and regulatory strategies in the postal sector 2018, pp. 299-312. [CrossRef]

- PD CEN/TS 16819:2015. Postal services. Parcel boxes for end use. Technical features. 2015. Standard ISBN: 978 0 580 88556 3.

- Agatz, N., Campbell, A., Fleischmann, M., & Savelsbergh, M. Time slot management in attended home delivery. Transportation Science 2011, 45(3), 435-449. [CrossRef]

- Mackert, J. Choice-based dynamic time slot management in attended home delivery. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2019, 129, 333-345. [CrossRef]

- Fallahtafti, A., Karimi, H., Ardjmand, E., & Ghalehkhondabi, I. Time slot management in selective pickup and delivery problem with mixed time windows. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2021, 159, 107512. [CrossRef]

- Otim, S., & Grover, V. An empirical study on web-based services and customer loyalty. European Journal of Information Systems 2006, 15(6), pp. 527-541. [CrossRef]

- Peng, D. X., & Lu, G. Exploring the impact of delivery performance on customer transaction volume and unit price: evidence from an assembly manufacturing supply chain. Production and Operations Management 2017, 26(5), pp. 880-902. [CrossRef]

- Garver, M.S., Williams, Z., Taylor, G.S., and Wynne, W.R. Modelling Choice in Logistics: A Managerial Guide and Application. International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management 2012, 42(2), pp. 128–51. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D. H., De Leeuw, S., Dullaert, W., & Foubert, B. P. What is the right delivery option for you? Consumer preferences for delivery attributes in online retailing. Journal of Business Logistics 2019, 40(4), pp. 299-321. [CrossRef]

- Rao S., Griffis S.E., Goldsby T.J. Failure to deliver? Linking online order fulfillment glitches with future purchase behavior. Journal of Operations Management 2011, 29(7-8), pp. 692-703. [CrossRef]

- Joerss, M., Neuhaus, F., & Schröder, J. How customer demands are reshaping last-mile delivery. The McKinsey Quarterly 2016, 17, pp. 1-5.

- Popli, A., & Mishra, S. Factors of perceived risk affecting online purchase decisions of consumers. Pacific Business Review International 2015, 8(2), pp. 49-58.

- Yang, L., Xu, M., & Xing, L. Exploring the core factors of online purchase decisions by building an E-Commerce network evolution model. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2022, 64, 102784. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, P., & Joshi, H. Factors influencing online purchase intention towards online shopping of Gen Z. International Journal of Business Competition and Growth 2020, 7(2), pp. 175-187. [CrossRef]

- van Gelder, K. Factors that influence online purchase decisions in the United States and the United Kingdom in 2022. Statista 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/628782/internet-user-purchase-influence-factors/ (accessed 30 June 2023).

- Chen, C.F., White, C., & Hsieh, Y.E. The role of consumer participation readiness in automated parcel station usage intentions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2020, 54, pp. 102063. [CrossRef]

- Meuter, M.L., Ostrom, A.L., Bitner, M.J., & Roundtree, R. The influence of technology anxiety on consumer use and experiences with self-service technologies. Journal of Business Research 2003, 56(11), pp. 899-906. [CrossRef]

- Vo, K.N., Le, A.N.H., Thanh Tam, L., & Ho Xuan, H. Immersive experience and customer responses towards mobile augmented reality applications: The moderating role of technology anxiety. Cogent Business & Management 2022, 9(1), 2063778. [CrossRef]

- Gelderman, C.J., Paul, W., & Van Diemen, R. Choosing self-service technologies or interpersonal services—The impact of situational factors and technology-related attitudes. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2011, 18(5), pp. 414-421. [CrossRef]

- Alloulbi, A., Öz, T., & Alzubi, A. The use of artificial intelligence for smart decision-making in smart cities: a moderated mediated model of technology anxiety and internal threats of IoT. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2022, 2022, 6707431. [CrossRef]

- Yuen, K. F., Wang, X., Ng L.T.W, & Wong, Y.D. An investigation of customers’ intention to use self-collection services for last-mile delivery, Transport Policy 2018, 66, pp. 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Neto, L. G., & Vieira, J. G. V. An investigation of consumer intention to use pick-up point services for last-mile distribution in a developing country. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2023, 74, 103425. [CrossRef]

- Yuen, K.F., Wang, X., Ma, F., & Wong, Y.D. The determinants of customers’ intention to use smart lockers for last-mile deliveries. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2019, 49, pp. 316-326. [CrossRef]

- Kedia, A., Kusumastuti, D., & Nicholson, A. Acceptability of collection and delivery points from consumers’ perspective: A qualitative case study of Christchurch city. Case Studies on Transport Policy 2017, 5(4), 587-595. [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, J. S., & Figliozzi, M.A. Spatial accessibility and equity analysis of Amazon parcel lockers facilities. Journal of Transport Geography 2021, 97, 103212. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.T., & Tiwasing, P. Customers’ intention to adopt smart lockers in last-mile delivery service: A multi-theory perspective. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2021, 61, 102514. [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, Y., & Golany, B. A parcel locker network as a solution to the logistics last mile problem. International Journal of Production Research 2018, 56(1-2), pp. 251-261. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J., & Lyu, J. Personal values as determinants of intentions to use self-service technology in retailing. Computers in Human Behavior 2016, 60, pp. 322-332. [CrossRef]

- Milioti, C., Pramatari, K., & Kelepouri, I. Modelling consumers’ acceptance for the click and collect service. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2020, 56, 102149. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, L. K., Morganti, E., Dablanc, L., & de Oliveira, R.L.M. Analysis of the potential demand of automated delivery stations for e-commerce deliveries in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. Research in Transportation Economics 2017, 65, pp. 34-43. [CrossRef]

- Rai, H.B., Verlinde, S., & Macharis, C. Unlocking the failed delivery problem? Opportunities and challenges for smart locks from a consumer perspective. Research in Transportation Economics 2021, 87, 100753. [CrossRef]

- Lai, P.L., Jang, H., Fang, M., & Peng, K. Determinants of customer satisfaction with parcel locker services in last-mile logistics. The Asian Journal of Shipping and Logistics 2022, 38(1), pp. 25-30. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H. Evaluating service quality of airline industry using hybrid best worst method and VIKOR. Journal of Air Transport Management 2018, 68, pp. 35-47. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., & Shang, H. Service quality, perceived value, and citizens’ continuous-use intention regarding e-government: Empirical evidence from China. Information & Management 2020, 57(3), 103197. [CrossRef]

- Durmaz D. Analysis of the level of customer service quality on the example of Inpost. Engineering thesis. 2022 (promoter: Maria Cieśla).

- Motyka M. Research on the preferences of users of InPost services in the field of self-service drop-off and pick-up points in the city of Żory. Engineering thesis. 2022 (promoter: Maria Cieśla).

- Mosur K. Analysis of the quality level of courier services on the example of Inpost. Engineering thesis. 2022 (promoter: Maria Cieśla).

- Kopała P. Improving the customer service process of courier services on the example of InPost. Engineering thesis. 2023 (promoter: Maria Cieśla).

- Czechowski M. Testing the quality of the customer service process of courier services at the sending and receiving points Engineering thesis. 2023 (promoter: Maria Cieśla).

- Kano, N. Attractive quality and must-be quality. Journal of the Japanese society for quality control 1984, 31(4), 147-156.

- Berger, C. Kano’s methods for understanding customer-defined quality. Center for quality management journal 1993, 2(4), 3-36.

- Wang, T., & Ji, P. Understanding customer needs through quantitative analysis of Kano’s model. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management 2010, 27(2), 173-184. [CrossRef]

- Mikulić, J., & Prebežac, D. A critical review of techniques for classifying quality attributes in the Kano model. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal 2011, 21(1), 46-66. [CrossRef]

- Witell, L., Löfgren, M., & Dahlgaard, J. J. Theory of attractive quality and the Kano methodology–the past, the present, and the future. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 2013, 24(11-12), 1241-1252. [CrossRef]

- Kermanshachi, S., Nipa, T.J., & Nadiri, H. Service quality assessment and enhancement using Kano model. Plos One 2022, 17(2), e0264423. [CrossRef]

- Zobnina, M., & Rozhkov, A. Listening to the voice of the customer in the hospitality industry: Kano model application. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes 2018, 10(4), 436-448. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P., & Srivastava, R.K. Customer satisfaction for designing attractive qualities of healthcare service in India using Kano model and quality function deployment. MIT International Journal of Mechanical Engineering 2011, 1(2), 101-107.

- Pai, F.Y., Yeh, T.M., & Tang, C.Y. Classifying restaurant service quality attributes by using Kano model and IPA approach. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 2018, 29(3-4), 301-328. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.J., Yeh, T.M., Pai, F.Y., & Chen, D.F. Integrating refined kano model and QFD for service quality improvement in healthy fast-food chain restaurants. International journal of environmental research and public health 2018, 15(7), 1310. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z., Wang, L., & Dong, Y. Research on innovative design of community mutual aid elderly care service platform based on Kano model. Heliyon 2023, 9(5). [CrossRef]

- Xie, M., & Kim, H.B. User acceptance of hotel service robots using the quantitative kano model. Sustainability 2022, 14(7), 3988. [CrossRef]

- Shahin, A., Pourhamidi, M., Antony, J., & Hyun Park, S. Typology of Kano models: a critical review of literature and proposition of a revised model. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management 2013, 30(3), 341-358. [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.H. Application of Refined Kano’s Model to Shoe Production and Consumer Satisfaction Assessment. Sustainability 2021, 13(5), 2484. [CrossRef]

- Schvaneveldt, S.J., Enkawa, T., & Miyakawa, M. Consumer evaluation perspectives of service quality: evaluation factors and two-way model of quality. Total quality management 1991, 2(2), 149-162. [CrossRef]

- Matzler, K., & Hinterhuber, H.H. How to make product development projects more successful by integrating Kano’s model of customer satisfaction into quality function deployment. Technovation 1998, 18(1), 25-38. [CrossRef]

- Shahin, A., & Mohammadi Shahiverdi, S. Estimating customer lifetime value for new product development based on the Kano model with a case study in automobile industry. Benchmarking: An International Journal 2015, 22(5), 857-873. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q., Jiao, R.J., Yang, X., Helander, M., Khalid, H.M., & Opperud, A. An analytical Kano model for customer need analysis. Design studies 2009, 30(1), 87-110. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.M., Chau, K.Y., Xu, D., & Liu, X. Consumer perceptions to support IoT based smart parcel locker logistics in China. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2021, 62, 102659. [CrossRef]

- Niederprüm, A., & van Lienden, W. Parcel locker stations: A solution for the last mile? (No. 2). WIK Working Paper. 2021. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/253743/1/WIK-WP-No2.pdf (accessed 15 July 2023).

- Akdoğan, K., & Özceylan, E. Parcel Locker Applications in Turkey. Beykent Üniversitesi Fen ve Mühendislik Bilimleri Dergisi 2023, 16(1), 43-54. [CrossRef]

- Stojanov, M. Automated parcel terminals-commercialization of the system for automated post services. Известия на Съюза на учените-Варна. Серия Икoнoмически науки 2022, 11(2), 21-28.

- Ji, S.F., Luo, R.J., & Peng, X.S. A probability guided evolutionary algorithm for multi-objective green express cabinet assignment in urban last-mile logistics. International Journal of Production Research 2019, 57(11), 3382-3404. [CrossRef]

- Lagorio, A., & Pinto, R. The parcel locker location issues: An overview of factors affecting their location. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Information Systems, Logistics and Supply Chain: Interconnected Supply Chains in an Era of Innovation, ILS. April 2020. pp. 414-421.

- Wróbel-Jędrzejewska, M., & Polak, E. The operation analysis of the innovative MainBox food storage device. Applied Sciences 2021, 11(16), 7682. [CrossRef]

- An, H.S., Park, A., Song, J.M., & Chung, C. Consumers’ adoption of parcel locker service: protection and technology perspectives. Cogent Business & Management 2022, 9(1), 2144096. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.H., Yu, T.S., & Lim, S.J. An Unmanned Smart Parcel Locker System with a Parcel Sterilizer. Journal of Computational and Theoretical Nanoscience 2021, 18(5), 1530-153. [CrossRef]

- Keen, C.C., Liang, C.H., & Sham, R. The effectiveness of parcel locker that affects the delivery options among online shoppers in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. International Journal of Logistics Systems and Management 2022, 41(4), 485-502. [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Lorente, J., Gabor, A. F., & Ponce-Cueto, E. Omnichannel logistics network design with integrated customer preference for deliveries and returns. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2020, 144, 106433. [CrossRef]

- Iyer, P., Veldman, R., & Zhang, Y.Universal Locker Systems for urban areas. In 53rd ORSNZ Annual Conference. December 2019.

- Lachapelle, U., Burke, M., Brotherton, A., & Leung, A. Parcel locker systems in a car dominant city: Location, characterisation and potential impacts on city planning and consumer travel access. Journal of Transport Geography 2018, 71, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Bi, M., Lai, J., & Chen, Y. Locating movable parcel lockers under stochastic demands. Symmetry 2020, 12(12), 2033. [CrossRef]

- Schwerdfeger, S., & Boysen, N. Who moves the locker? A benchmark study of alternative mobile parcel locker concepts. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 2022, 142, 103780. [CrossRef]

- Lazarević, D., Dobrodolac, M., & Marković, D. Implementation of Mobile Parcel Lockers in Delivery Systems–Analysis by the AHP Approach. International Journal for Traffic and Transport Engineering 2023, 13(1). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).