1. Introduction

The evolution of contemporary economic development, shifts in work styles, and the imperative for innovative production have triggered organizational changes, impacting both workspace design and the organizational structure. Enterprises now face the continual need to innovate their products or services to bolster core competitiveness. Consequently, the strategies for fostering corporate innovation and sustainable development have emerged as a pivotal research area in the twenty-first century. Initial research concentrating on individual employee creativity within organizations bears certain limitations (Styhre & Sundgren,2005[

1]). However, a prevailing focus in contemporary organizational research revolves around investigating environmental elements that exert influence on employee innovation at the organizational level. Given the intricate nature of organizational surroundings, divergent viewpoints on the relationship between innovation and the environment emerge across various disciplines. Despite the extensive historical research delving into innovation through the lenses of organizational sociology and architecture, the amalgamation of these perspectives to explore innovation remained a relatively unexplored avenue until recent times. Organizational culture and climate, as the most important organizational factors affecting innovation(Andriopoulos, 2001)[

2], have become a hot topic of interdisciplinary research by exploring the impact of the physical environment on organizational culture in organizations(Kallio et al.,2015)[

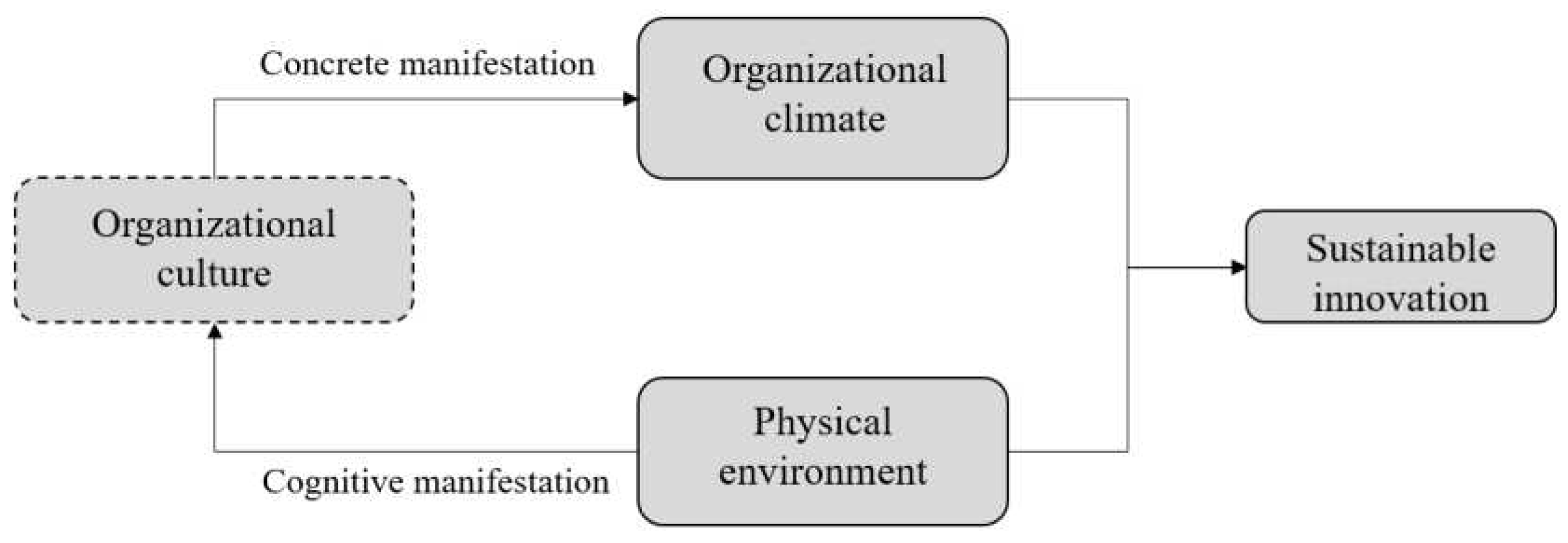

3]. Organizational climate, viewed as a distinct facet of organizational culture(Ahmed,1998; Chan,1998;Schneider et al., 2002)[

4,

5,

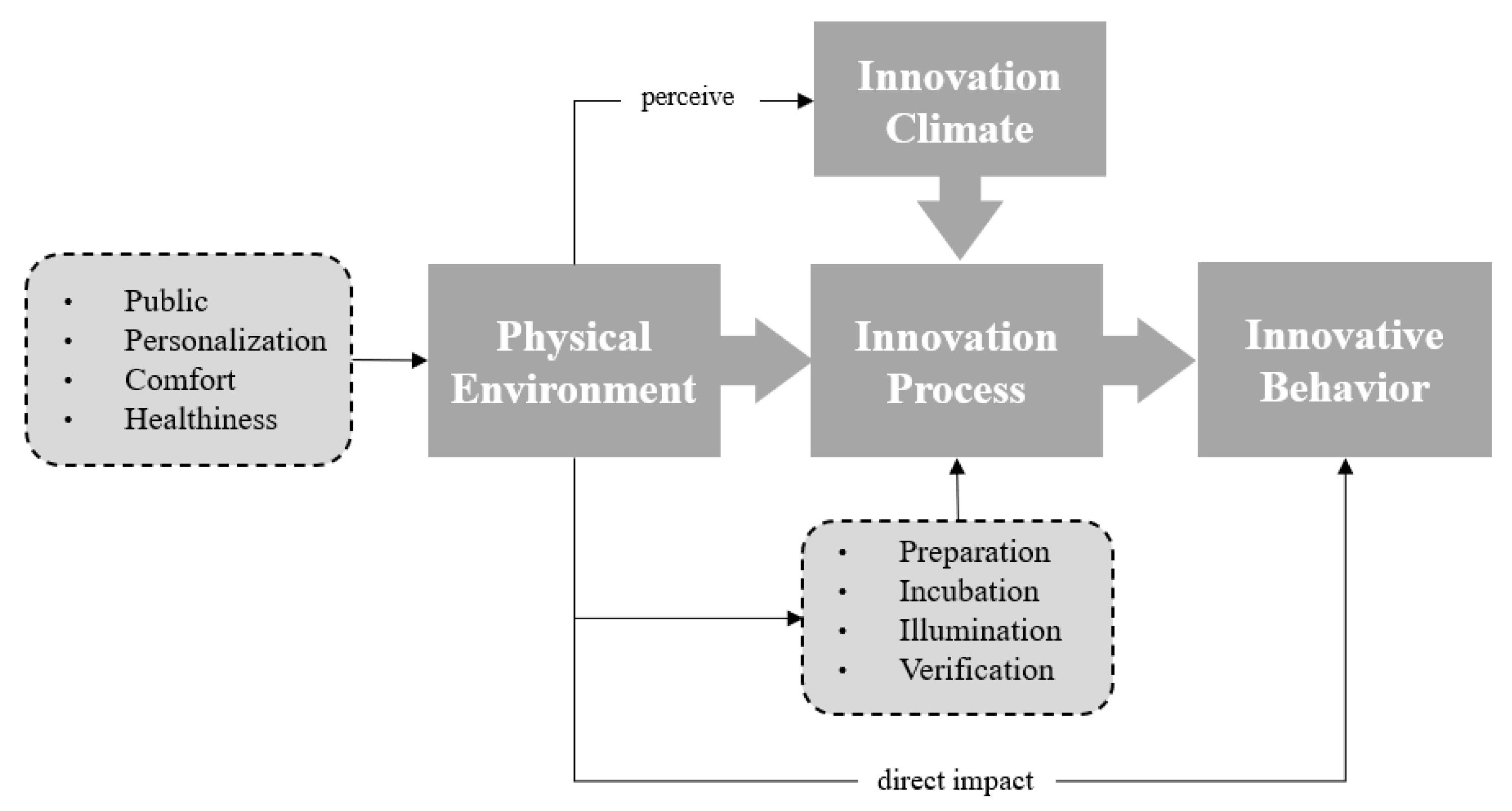

6], warrants a deeper investigation into its correlation with physical space, particularly in its role in promoting innovation (

Figure 1). This paper narrows its focus to the realm of ambient and physical environments within organizations, delving into the interconnectedness of these elements in driving sustainable innovation.

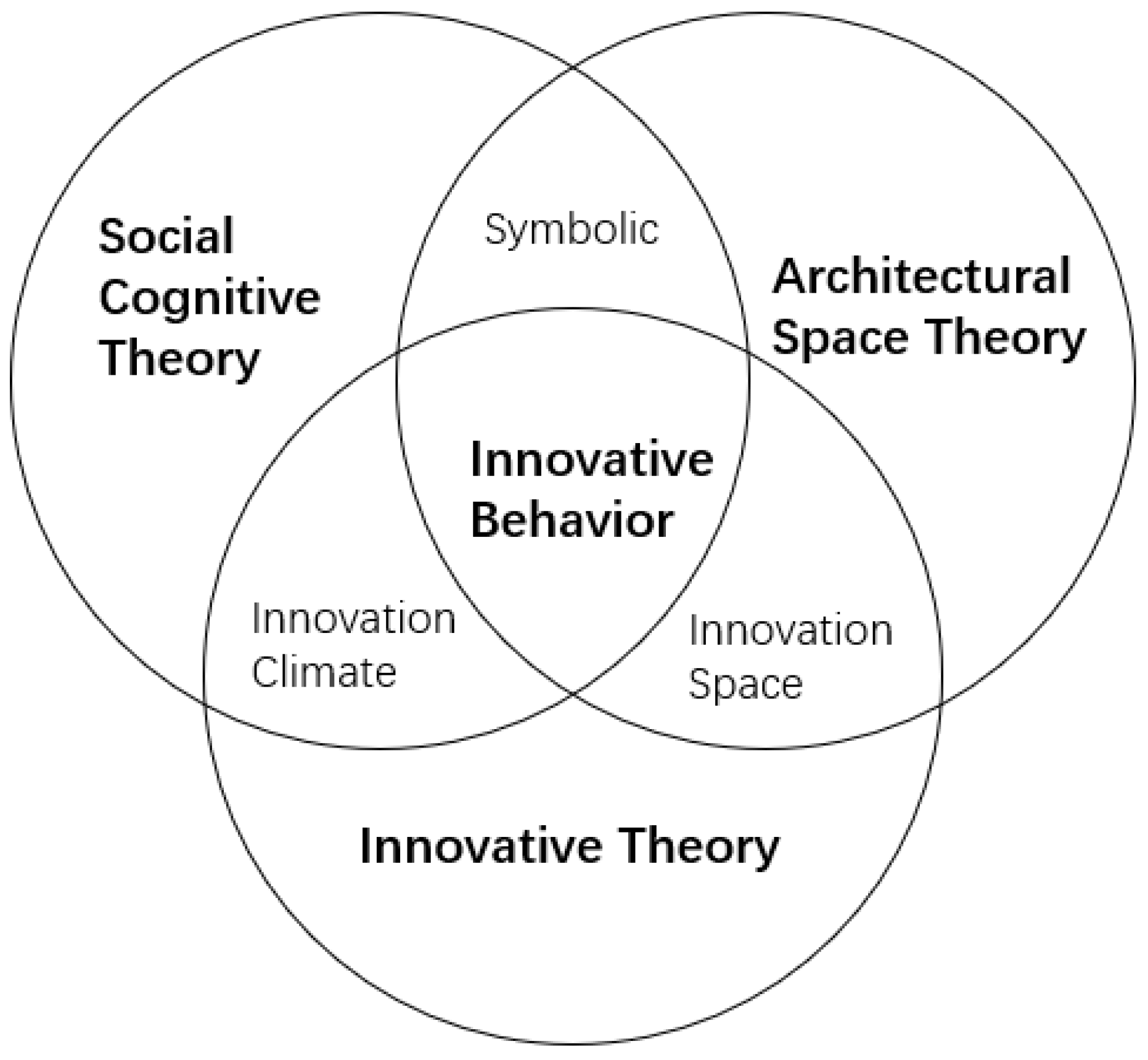

Exploring the promotion of sustainable innovative organizational environments necessitates the delineation of three distinct trajectories within academic research: innovation behavior, the physical spatial organization within organizations, and the ambient milieu within these establishments. The disciplinary demarcations that separate sociology and architecture impose challenges on scholars within each domain, hindering a holistic comprehension of organizational environments. Despite architecture's comprehensive scrutiny of office environments (Vilnai et al., 2005) [

7], it falls short in investigating the attributes of physical spaces conducive to innovation, lacking a systematic framework akin to that in sociology. This paper takes its inception from the vantage point of innovation behavior, amalgamating the social context with physical spatial considerations. Through this approach, we aim to unearth the gaps existing in the exploration of the interconnectedness between sociology and architecture in the sphere of innovation research. Our objective is to furnish theoretical augmentation for designing office spaces that foster innovation behavior. We also advocate for parity in the attention devoted to both physical space and operational management in the realms of research and practical implementation of innovation, a call directed towards scholars and entrepreneurs alike. Consequently, this paper's analysis predominantly gravitates toward the realm of architectural research. Our intention is to comprehensively review and encapsulate the cross-pollination of the physical spatial environment and the atmosphere conducive to sustainable innovation. The research content encompasses the following areas:

1. Establish a three-dimensional analysis framework of social cognition, workspace, and innovation to guide the association studies of atmosphere, space, and behavior (

Figure 2).

2. Based on the three-dimensional framework, summarize the research on the association between social environment, physical environment, and sustainable innovation respectively.

3. Analyze the mechanism of correlation between atmosphere and space in the context of sustainable innovation, and propose future research avenues, as well as theoretical research directions of spatial design that can promote innovation.

2. Innovation and Organizational Environment

2.1. Innovation and Creativity

The term "innovation" has been extensively explored from a multidisciplinary perspective. Scott and Bruce (1994)[

8] assert that innovation constitutes a process encompassing both idea generation and implementation. In research, "innovation" and "creativity" are often utilized interchangeably. Amabile et al. (1996)[

9] propose that individual and collaborative creativity serves as the foundational bedrock for innovation. They contend that creativity acts as both the precursor and outcome of the innovation process (Winks et al. 2020)[

10]. While creativity pertains to the formulation of original and useful concepts (Mumford and Gustafson, 1988 ) [

11], innovation revolves around the adoption and realization of these novel and valuable ideas (Kanter, 1988)[

12]. It is imperative to recognize that innovation and creativity are symbiotic, mutually reinforcing elements, differing in emphasis more than they do in substance (West & Farr, 1990). Therefore, the definition of innovation adopted within this paper encompasses the entirety of the process involving the generation and implementation of novel ideas, or the creation of novel entities within an organizational context, inherently encapsulating creativity as an integral component.

2.2. Physical, Social, and Organizational Environments

Human behavior is not solely propelled by intrinsic factors like motives and attitudes; it can also be influenced by impromptu actions triggered by the surroundings. Social cognitive theory underscores the dynamic interplay between the individual and their environment. Within this framework, the components of the individual, their behavior, and the environment coexist independently while simultaneously interconnecting and shaping one another(Bandura,1986)[

10]. In this paper, the organizational environment is divided into the objective physical environment and the social environment(Morton et al.,2016; Billie & Robert,2002)[

13,

14]. The physical environment is defined using Stephenson et al. (2020) [

15]: as the built environments that emerge from organizational activities, objects, arrangements, and social practices. Repetti(1987)[

16] categorized the work social environment into common and individual social environments. This paper focuses on the analysis of the common social environment, which means that the social climate is shared by employees in the same work setting. While achieving a comprehensive understanding of organizational environments demands interdisciplinary investigation, research into physical spaces frequently remains siloed and explored within specific disciplines that extend beyond the customary realms of organizational behavior and management. These encompass fields like architecture, environmental psychology, facilities management, and education (Brown et al., 2005; Orlikowski,2010) [

17,

18]. The following section explores the relationship between the physical (

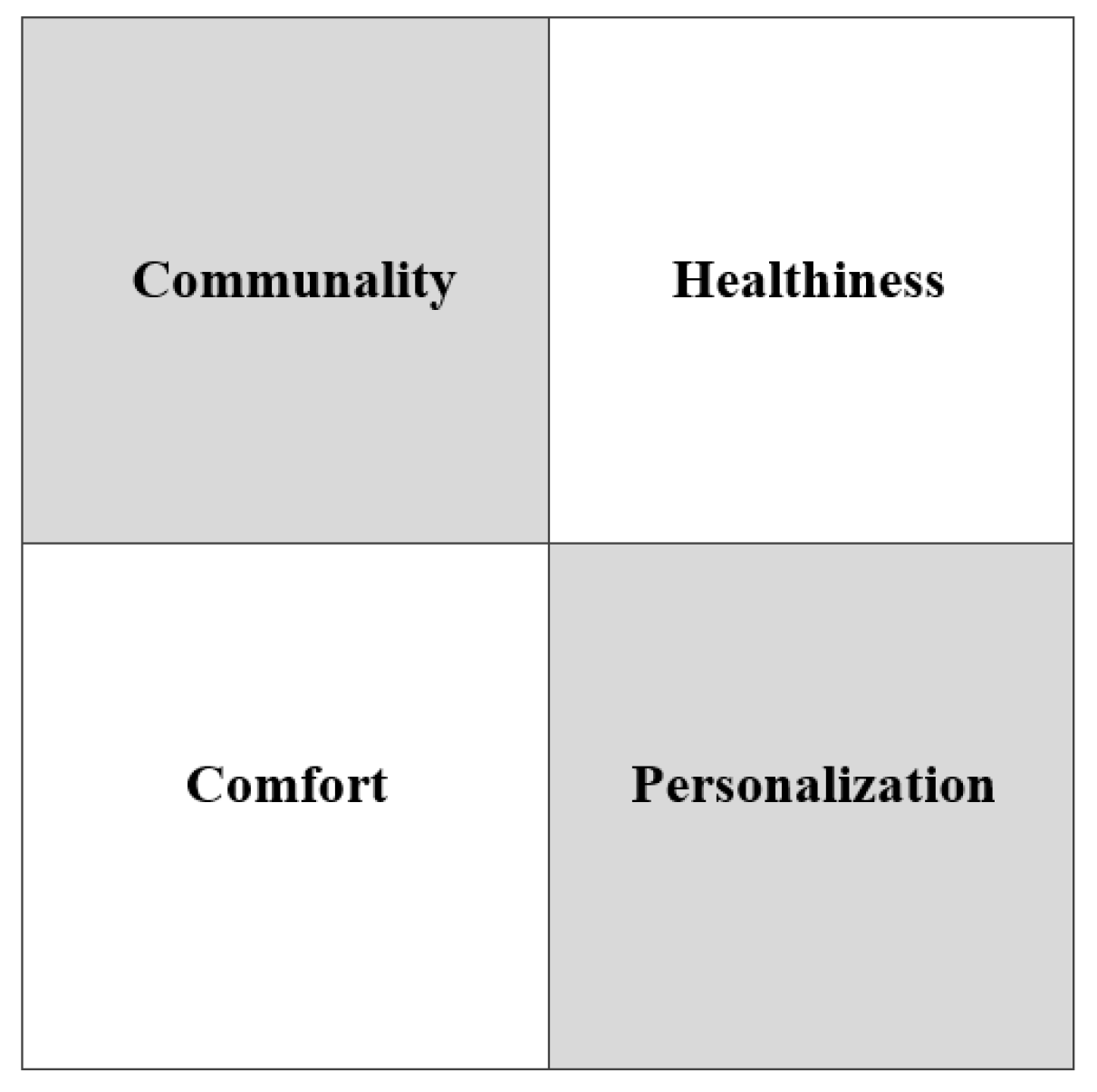

Figure 3) and ambient environments and behavior, respectively, and discusses the similarities between the two that influence behavior, providing a basis for summarizing the discussion of the innovation climate and spatial associations.

2.2.1. Physical Working Environment

Hall(1966)[

19]Suggests that the physical environment can influence the behavior of human interactions through scales that affect individuals differently. Therefore, this paper adopts a viewpoint centered on spatial openness and individual perception, and the physical characteristics of the work environment are classified into four elements: communality, personalization, comfort, and healthiness.

At the spatial scale, researchers have focused on the communal attributes of space in terms of communication and interaction between employees [

20](Blomberg and Kallio,2022). Allen (1977) [

21] was among the first to quantitatively establish a connection between spatial components and social behavior. His research highlighted that as the distance between workstations increased, the frequency of communication decreased. This pioneering study by Allen catalyzed increased scholarly interest in elucidating the mechanisms that interconnect the public attributes of the physical environment with communication and collaboration.(Eric & Mary,1986[

22]; Hatch,1987[

23]; Lile et al.,2009[

24]; Wineman et al.,2009[

25]; Salazar and Claudel,2022[

26]). The personalization of space pays more attention to the impact of personal-scale spatial elements such as workstations on the individual's own emotions and perceptions. (Ainsworth et al.,1993;Jiang et al.,2021;Ko et al.,2020)[

27,

28,

29].

From the personal perception perspective, the healthiness of space primarily manifests in the caliber of the indoor environment, encompassing factors like lighting, temperature, humidity, and ventilation(Ko et al., 2020; Khoshbakht et al., 2021; Zhuang et al., 2022)[

29,

30,

31]. These aspects exert an influence on employees' physical sensations, which can indirectly affect employee productivity or organizational performance. With the emphasis on exercise, researchers have begun to look at how workplace layout design can promote physical activity to improve employee health(Candido et al.,2019)[

32]. The comfort of a space can be evaluated from two distinct angles. Firstly, cognitive comfort encompasses the sense of spaciousness within the environment (Zhuang et al., 2022)[

31], as well as the aesthetic qualities of its decor (Ainsworth et al., 1993)[

27], both of which contribute to heightened job satisfaction. Secondly, physical comfort pertains to ergonomically designed furniture, which has been substantiated by research to enhance employees' efficiency.

2.2.2. Organizational Climate Environment

Starting from the 1960s, organizational climate has gained increasing attention from organizational researchers as a critical aspect of the human social environment. Through the lens of the shared cognitive approach, there is a general consensus among researchers that organizational climate pertains to members' perceptions or experiences of the prevailing organizational environment (James et al., 2008) [

33]. It represents a systematic organizational attribute, formed by the collective perceptions of members about the organizational environment, ultimately influencing their behaviors (Litwin & Stringer, 1968; Sleutel, 2000) [

34]. Numerous studies have demonstrated the significant impact of organizational climate on employee behavior and psychology y (Anderson & West, 1998; James et al., 2008) [

33,

35]. The diverse nature of organizational climate dictates that different climate elements wield varying effects on employee behaviors. Schneider et al. (2013) [

36] posit that organizational climate can be categorized into result-oriented and process-oriented climates based on their core orientations. Researchers investigating climate often center their attention on specific policies, practices, and procedures as the sources of individuals' perceptions. They delve into how employees perceive the outcomes of the organization's management (e.g., service quality, safety, innovation) and the corresponding internal processes (e.g., fairness, ethics, inclusivity). It is contended that climate serves as behavioral evidence reflecting the cultural attributes of the work environment. These behaviors, in turn, constitute the foundation upon which employees formulate their perceptions of the organization's values and beliefs.

2.2.3. Connections Among Physical Environment, Social Environment, and Innovation

Until recently, the consideration of the multidisciplinary impact of the environment on behavior has not received adequate attention. Frank (1984) argued that the environment's influence on behavior is not singular and direct, but rather a convergence of physical and social factors that collectively shape it. Olikowsik (2010) [

18] contended that the conventional realm of management overlooks the intricate connection between organizations and the tangible spaces that underlie human actions and interactions. He advocated for the simultaneous exploration of physical space and organizational environments, shedding light on the intricate ways in which society and matter interact in everyday life.

Present perspectives on the interplay between behavior and social and physical environments are categorized into two primary streams. The first perspective underscores the intricate entwinement of physical and social environments. Billie and Robert (2002) [

13] argued that the physical environment serves as a necessary support for behavior, ranking second only to personal and social determinants in influencing behavior. Lukersmith and Burgess (2013) investigated healthcare workers' creativity by considering job content and leadership as social variables and interior decoration, sound, light, and heat as physical variables. They concluded that the social and physical environments collaboratively stimulate creativity, with the social environment wielding a more potent influence on creativity than the physical environment. However, there are scholars who contend that the physical and social environments exert separate and independent influences on behavior. For instance, Dul (2011) [

37] examined the impact of the physical work environment on the creativity of knowledge workers. Through a questionnaire survey involving 274 knowledge workers, it was discerned that creative personality, social and organizational environment, and physical work environment distinctly and progressively influence creative performance.

3. Method

The above summarizes the elements of physical space and organizational climate that affect employees, respectively, and summarizes the current research perspectives on the relationship between the social and physical environments based on innovation: The physical and social environments have been recognized by scholars in both theoretical and empirical research on innovation, but there is no clear description of the elements of the physical environment that affect innovation, and how they work together with the social environment to support innovation. In the subsequent sections, the authors aim to address these gaps. Firstly, restructuring the existing research findings concerning innovation and the physical environment, anchoring their analysis on the four identified elements of the physical environment that impact employees. Secondly, the authors delve into the innovation climate, a pivotal facet of the social environment influencing innovation. They explore the present status of research examining its connection with the physical environment and introduce a framework for contemplating how the climate and space collaborate to foster innovative behavior.

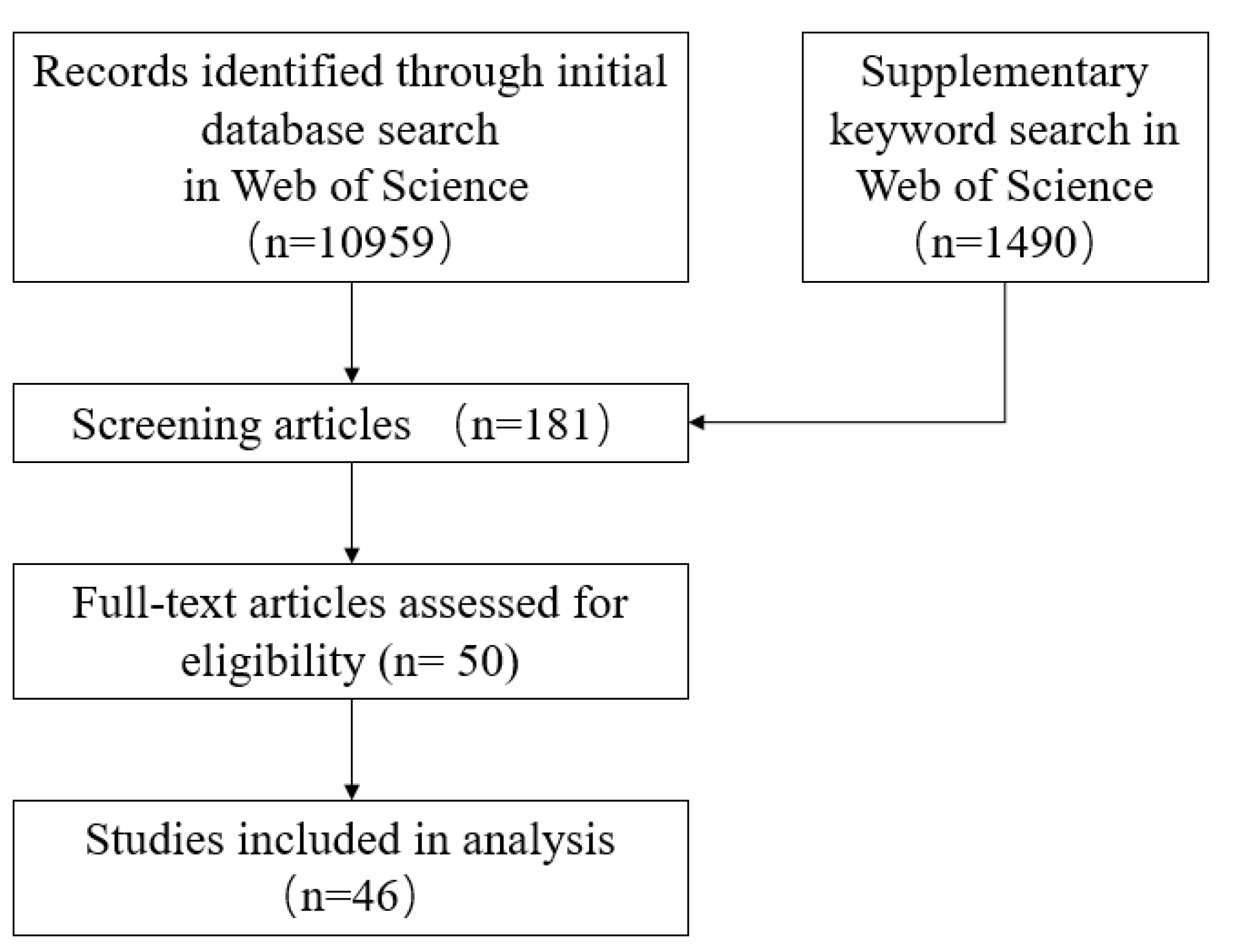

The literature collection process (

Figure 4) is structured into three distinct stages. In the initial stage, a search was conducted within the Web of Science database for English literature up to 2023, focusing on themes related to innovation and the physical environment. Keyword combinations "innovation AND physical environment", "innovation AND physical space", and "innovation AND space design" were employed to retrieve relevant sources. Furthermore, numerous studies have substantiated the pivotal role of communication and cooperation in fostering innovation. Social behaviors like collaboration and serendipitous interactions are perceived as tangible indicators or catalysts of innovation (Allen, 1977[

21]; Toker and Gray, 2008[

38]; Wagner et al., 2011[

39]; Yubo et al., 2021[

40]). Consequently, this paper extends the search by incorporating additional keywords, such as "collaboration communication AND physical environment" et al, was utilized to comprehensively explore the literature landscape. By excluding research areas such as urban planning scales, a total of 181 research papers were identified. Through two rounds of manual screening, the titles, keywords, and abstracts of these papers were scrutinized to ascertain their relevance to either physical space and innovation or physical space and communication. The objective was to ensure that the literature under consideration explored innovation from a materiality standpoint. Ultimately, 46 papers were deemed suitable for analysis.

In the third stage, the innovation climate's constituent elements and influencing mechanisms, pertaining to the physical environment, were distilled. This synthesis was based on the elements and mechanisms elucidated in the research literature retrieved during the earlier stages.

4. Result

4.1. Physical Environment and Innovation

The significance of the physical environment as a catalyst for innovation has garnered recognition within both theoretical and empirical inquiries within the innovation realm. Researchers have embarked on contemplating the design attributes of the physical environment that wield influence over innovation (

Table 1). This paper seeks to encapsulate the amalgamated research literature by categorizing how the physical environment shapes innovation from the standpoint of individuals utilizing the space. This classification revolves around four distinct characteristic elements: public, personalization, comfort, and healthiness (

Table 2).

4.1.1. Communality

The spatial delineation of layout proximity encompasses three dimensions: within the office, within the building, and between the office building and adjacent regional spaces. Within the office, Hatch (1987) [

23], conducting observations and interviews within two technology companies, discovered that office employees situated farther away from the office entrance had fewer interactions. Additionally, it was found that the presence of fewer obstacles—translating to easier pathways—within the office contributed to a higher frequency of interactions. There is evidence to suggest that interprofessional interactions were more frequent among practitioners sharing the same office ( Bouncken & Aslam, 2019) [

45]. Within a building, research indicates that the distance between offices directly impacts collaborative innovation. Longer distances between offices are associated with a reduced likelihood of collaborative innovation (Winema et al., 2009) [

25]. Moreover, a higher overlap of shortest paths between researchers in various functional domains within a building corresponds to an elevated probability of collaborative innovation (Kabo et al., 2014) [

46]. Salazar and Claudel (2022) [

26]demonstrated that researchers operating within the same building exhibit an increased likelihood of engaging in collaborative innovation. Toker and Gray (2008) [

47], in a case study, identified that a closer distance between offices and laboratories enhances the probability of face-to-face consultations, subsequently influencing innovation research. Sevtsuk et al. (2022) [

48] showcased that reduced distances between offices correlate with a higher likelihood of email exchanges within the same building. Ying et al. (2010[

49], 2011[

50]) revealed that shorter distances between meeting rooms and workstations amplify the probability of collaboration. Yacoub and Haefliger (2022) [

51] gleaned from interviews with employees across various firms on the same floor that closer common workspaces facilitate communication among employees not directly affiliated with the same firm, fostering potential for collaborative innovation. Moreover, the urban surroundings surrounding a building can also sway employees' innovative behaviors at work. Moultrie et al. (2007) [

43] posited that the geographical location of the work environment influences employees' communication efficiency and innovation potential, both within the office and on the company's shop floor. Yubo et al. (2021) [

40] highlighted interdisciplinary chance encounters as a mechanism to nurture innovation. Employing a spatial syntax approach to quantify the complexity of buildings within a university, their analysis disclosed that proximity in path links between teaching spaces, canteens, and accommodations heightens the likelihood of serendipitous encounters and exchanges. Xia et al. (2022) [

52] introduced the concept of multidisciplinary innovation (MDI) and evaluated it through campus spatial organization networks and social networks. Their study found that the proximity of campus spaces positively influences interdisciplinary communication links.

The appearance of the environment is important because it reflects the values and norms of people and organizations (Kelly, 2002) [

53], and is the substance that is most intuitively perceived by people through vision. An attractive work environment can be inspiring and stimulate innovation among employees in an office environment (Haner, 2005) [

54]. Creating a creative appearance is the main motivation for designing a creative office, which can increase the motivation of office workers, which in turn improves productivity (Crawford, 2018) [

55]

.

4.1.2. Personalization

The decor of the physical environment is a reflection of the unique attributes of the organizational context. For optimal innovation stimulation, space design should be customized to cater to different activities, cognitive intensities, and personal inclinations (Martens, 2011) [

56].McCoy and Evans (2002) [

57] conducted research into the impact of visually perceivable interior design elements—such as materials, colors, and shapes—on creativity, utilizing a comparative quasi-experimental approach. Their study unveiled that the utilization of more natural materials, incorporation of natural environmental components, and minimal usage of cool colors and artificial materials can foster employee creativity. Similarly, Ceylan et al. (2008) [

58]demonstrated that well-executed office interior design has the potential to stimulate employee creativity. Colors, albeit indirectly, can influence creativity by impacting visual perceptions. In Lukersmith and Burgess' (2013) [

59] study, healthcare workers reported that calming colors in their work environment—like those on painted walls or furniture—supported their creativity or creative potential within the workspace. Dul and Ceylan (2011) [

60], based on a questionnaire survey involving 30 companies, found that the presence of inspiring decorative colors in the physical work environment fosters employees' autonomy in their work, subsequently fostering creativity in their tasks.

The layout of a workspace establishes spatial boundaries, reconfiguring building space and consequently impacting spatial accessibility and visibility. Changes in these boundaries can influence the perception of spatial accessibility and visibility. The visibility of workstations can significantly influence users' sense of psychological safety. Limited visibility tends to have a detrimental effect on communication and collaboration (Stryker et al., 2012) [

61]. Contrary to common perception, open-plan workspaces do not necessarily foster face-to-face employee communication and interaction (Bernstein and Turban, 2018) [

62]. Employees situated in neighboring workspaces are more inclined to interact when within each other's shared field of view (Peponis et al., 2007) [

63], potentially fostering communicative innovation. In Lukersmith and Burgess's study (2013) [

59], spatial privacy emerged as the most influential factor among physical elements like interior decoration and the acoustic environment, significantly affecting creativity according to questionnaire analysis. Motalebi and Parvaneh (2021) [

64], in their focus on the indoor spatial elements impacting artists' creativity, discovered through questionnaires and interviews with 40 artists that privately customized spaces induce relaxation and enhance creative thinking ability. They posited that personalization and a sense of security emerge as two pivotal characteristics of an innovative space conducive to creative work. Kristensen (2004) [

65] illustrated via a case study that personal workstations play a central role in influencing the initial stage of innovation, highlighting the importance of catering to individual activity needs.

Across various phases of innovation, individuals exhibit diverse behaviors and, consequently, necessitate distinct acoustic environments. For instance, certain employees necessitate a tranquil environment to concentrate, while others thrive in a communicative atmosphere conducive to innovation promotion. Noise within office settings hampers communication efficiency, undermines organizational cohesion, and disrupts the thought processes crucial to the innovation journey (Clements-Croome, 2006)[

66]. Martens (2011) [

56]identified through interviews with creative individuals that noise could potentially hinder their creative work. However, the appropriate ambiance of work-related sounds can actually stimulate creativity. Lukersmith and Burgess (2013) [

59], in a questionnaire study involving healthcare workers, identified sound within the work environment as a prospective element for fostering creativity. They suggested various ways to improve the sound environment, such as incorporating sound barriers, employing damping features on flooring surfaces, and providing designated spaces for background or mood music.

4.1.3. Comfort

A generous office space contributes to a comfortable user experience and bolsters job satisfaction (Maryam et al., 2021[

30]; Dian et al., 2022[

31]). Ying et al. (2011) [

50] conducted research incorporating workstation size and workplace space density (the number of employees within a 25-foot radius) as physical variables. They employed a collaboration perception questionnaire and identified a negative correlation between spatial density and collaboration perception. The study highlighted the importance of providing employees with spacious and comfortable workspaces to facilitate collaboration and innovation. In spaces dedicated to innovation, the presence of materials for prototyping and whiteboards for visualizing ideas allows employees to concretize their concepts. This in turn enhances communication comfort and increases the likelihood of innovation (Moultrie et al., 2007) [

43].

4.1.4. Healthiness

An ample presence of natural elements can significantly enhance both physical and mental well-being, impacting work innovation through visual perception. Incorporating indoor greenery has been demonstrated to enhance cognitive and creative performance (van den Bogerd et al., 2021[

67]; Shibata & Suzuki, 2004[

68]). Natural landscapes visible through windows can play a crucial role in the preparatory phase of innovation, stimulating visual senses and fostering the generation of novel ideas and heightened creativity (Plambech & Konijnendijk, 2015[

69]; Ko et al., 2020[

70]; Atchley et al., 2012[

71]; Yeh et al., 2022[

72]; Chulvi et al., 2020[

73]). Furthermore, the intensity of light is capable of influencing the conception and incubation of creative ideas by impacting personal perceptions such as attention and mood. This influence is especially prominent during the pre-innovation process (Steidle & Werth, 2013[

74]). Considering the perspective of physical perception, although some current studies have demonstrated the influence of air quality and ventilation on staff's job satisfaction and productivity (Fang et al., 2004) [

75], comprehensive research on the nexus between innovation and air quality is yet to be fully developed.

In terms of physical activity, researchers are increasingly examining the impact of open and exercise spaces on employees' physical well-being, communication, and interaction. Hua et al. (2010) [

49] evaluated the percentage of leisure and interaction areas in various office buildings along with employees' perceptions of collaboration. Their findings indicated that a smaller percentage of leisure and interaction areas correlated with lower perceived collaboration among employees, thereby hindering effective communication and innovation. Sailer (2011) [

76] analyzed leisure and exercise spaces' effects on employees' physical health, communication, and interaction by comparing the spatial layout of a media company's building before and after relocation. This analysis revealed that workplaces with a higher proportion of open spaces exhibited a greater likelihood of episodic communication. Candido et al. (2019)[

32] identified that engaging in physical activity during office hours not only promotes physical fitness but also heightens the likelihood of episodic communication. Such communication patterns, in turn, contribute to fostering innovation.

4.2. Physical Environment and Innovation Climate

4.2.1. Innovation Climate

The concept of innovation climate entails exploring the connection with innovation, building upon the study of organizational climate, which significantly contributes to enhancing employee creativity, organizational efficiency, and competitiveness. In accordance with Schneider et al.'s (2013) [

36] classification of organizational climate, innovation climate research is positioned as an investigation centered on organizational innovation as a strategic outcome. In this study, we delve into highly cited quantitative analyses of innovation climate, operating at the level of shared perceptions, and categorize them into team and organizational levels based on the research subjects' focus.

At the organizational level, for instance, Amabile et al. (1996)[

77] defines organizational innovation climate as the collective perceptions held by organizational members regarding the presence of an innovative environment within the organization. To assess this climate, Amabile employs the KEYS (Innovation Climate Evaluation Scale) to quantitatively examine elements of the organizational environment conducive to fostering innovation, such as the promotion of challenging goals and recognition for creative work. Scott and Bruce (1994) [

8] propose a model where individual innovative behavior arises from the interplay of four factors: the individual, the leader, the work group, and the organizational innovation climate. Empirical research conducted on employees of R& D companies by Scott and Bruce revealed that the dimension of innovation support within the organizational climate significantly influences individual innovative behavior. On the team level, Anderson and West (1998) [

35]introduce the Team Climate for Innovation (TCI) scale, comprising four dimensions: safety, support for innovation, willingness, and task orientation. They further break down safety into the security of participation and frequency of interaction into five dimensions. A majority of innovation climate research scales are adapted versions of these quantitative studies (Newman et al., 2019) [

78]. In this paper, we categorize elements from the aforementioned quantitative research on innovation climate into two orientations: those focused on stimulating the innovation process (e.g., encouragement, safety) and those aimed at realizing innovation (e.g., rewards, challenging). This categorization prepares the groundwork for exploring the associations between atmosphere and space in subsequent sections.

4.2.2. The relationship between the innovation climate and the physical environment

As early as the early 20th century, the concept of "cognitive maps" was introduced by Tomas (1926)[

80], which marked the first instance of associating individual perception with the environment. This connection between subjective perception and the environment laid the foundation for understanding how people perceive their surroundings. As Schneider et al. (2013) [

36] articulated, "atmosphere provides a way of accessing tangible things," encompassing both tangible elements and intangible factors within an environment that have the potential to deeply influence human psychology, thereby shaping work behaviors. The impact of the environment on human behavior has increasingly garnered attention from scholars within the field of organizational sociology. However, there remains a dearth of research literature focusing on the perception of the atmosphere and the physical environment through the lens of the architectural discipline. This paper proposes a model in which the physical environment and the innovation climate jointly influence the innovation process and, finally, innovation behavior (

Figure 5).

Climate serves as the underlying carrier of organizational culture, encapsulating the intangible aspects of culture that manifest through work processes, organizational objectives, and a series of observable behaviors that contribute to the "tangible" atmosphere. Culture, operating imperceptibly within the environment, wields a transformative influence on individuals' psychology and behavior. This transition from an intangible culture to a "tangible" atmosphere is pivotal in achieving this goal, as elucidated by Schneider et al. (2013) [

36]. A consensus exists among researchers that physical space can serve as a symbol of an organization's values and culture. Accordingly, it is stressed that physical environments conducive to fostering innovation should mirror the organization's culture and ethos of innovation (Rafaeli & Vilnai, 2004[

41]; Vilnai et al., 2005[

7]; de Vaujany and Mitev, 2013[

81]; Blomberg & Kallio, 2022[

20]). Notably, less emphasis has been placed on the "tangible" innovation climate within the physical space. Concurrently, the linkage between organizational innovation culture and organizational innovation climate sparks debate within the realm of management science. Ahmed (1998)[

4] delineates between innovation culture and innovation climate without explicitly defining their similarities and distinctions. In contrast, Panuwatwanich et al. (2008)[

82] identify organizational culture, leadership, and team climate as constituents of the innovation climate. Through empirical analysis, they ascertain that perceptible organizational culture moderates the other two elements of innovation climate, ultimately fostering innovation and subsequently impacting firm performance.

The interplay between physical space and innovation climate can also be mediated through various other conditions. An illustration of this is the work of Munir and Beh (2019) [

83], who establish that organizational innovation climate contributes to knowledge sharing, thereby fostering innovative work behaviors. Additionally, the capacity of communal physical spaces to significantly impact knowledge exchange and sharing in pursuit of collaboration is a consensus among most scholars (Wineman et al., 2009[

25]; Ying et al., 2011[

50]; Salazar & Claudel, 2021[

26]). Another dimension to consider is the influence of the innovation climate's element of interaction frequency, as articulated by Anderson and West (1998)[

35], on organizational innovation. This aspect of innovation climate aligns with how spatial layout can impact employee communication, a point underscored by research such as Eric and Marry (1986) [

22] and Ashkanasy et al. (2014) [

84]. These mediating conditions thus reinforce the intricate connections between physical space and innovation climate within organizational contexts.

5. Future Research Directions

5.1. Mechanisms Linking the Physical Environment and the Innovation Climate

To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between the physical environment and the climate for innovation, further investigation into the mechanisms through which the physical environment influences the innovation climate is recommended. This exploration should delve into questions such as: What is the nature of the connection between the physical space that supports innovation and the innovation climate? Are there any precursor conditions or interactive elements involved? How exactly do physical space and innovation climate collaboratively impact innovation behavior? Addressing these inquiries can deepen our comprehension of the intricate dynamics at play. Considering the present diversity in innovation climate assessment scales and the limited explanations for modifying established scales, this paper advocates for incorporating the influence of physical space into the framework. By integrating spatial factors, future research can enhance the refinement and adjustment of innovation climate scales.

Furthermore, the examination of space's interplay with other managerial components that affect the innovation climate, such as leadership (Lukersmith and Burgess-Limerick, 2013[

59]), could provide a more comprehensive insight. Leadership not only reflects an organization's culture but also its rules and guidelines. Another avenue to explore is the differentiation in the impact of various types of physical environments on the innovation climate. This endeavor can offer practical guidance for cultivating an innovation-friendly climate within organizations. Understanding the nuanced effects of different spatial setups on the innovation climate can aid in crafting tailored strategies for fostering an innovation-oriented atmosphere. In the pursuit of optimizing the innovation climate, organizations are encouraged to capitalize on the advantages offered by the physical environment. By harnessing the potential of the workspace, organizations can amplify their employees' creativity and innovation, thereby propelling the growth and advancement of the entire organization. In sum, the relationship between the physical environment and the innovation climate warrants thorough consideration, necessitating a multidimensional approach to cultivate an optimal innovation climate within organizations.

5.2. Innovative Symbols of Space and Social Cognition

While organizational culture, normative systems, and values as symbols of physical space have been confirmed by most scholars (Vilnai-Yavetz et al., 2005[

7]; Oksanen & Ståhle, 2013[

44]), the current development of firms aiming at sustainable innovation requires scholars to think further about how physical space can symbolize an organization's innovation. When diverse individuals with varying backgrounds and experiences come together within an organizational setting, their shared perception of the physical space contributes to the construction of a collective identity (Brown & Humphreys, 2005[

85]). This shared identity influences how individuals navigate and interact within the organization. In this context, the physical space plays a subtle yet significant role in shaping cultures that foster innovation. Notably, several scholars have confirmed the positive impact of space on the collectivist dimension of innovation culture (Kallio et al., 2015[

3]; Blomberg and Kallio, 2022[

20]). The intricate interplay between the innovation culture represented by the physical space and how this culture is collectively perceived by employees warrants further exploration and investigation. This avenue of inquiry holds the potential to uncover valuable strategies for cultivating an innovation culture that is not just symbolized by the space, but also deeply ingrained within the collective identity of the organization.

6. Conclusion

Research on the relationship between the physical environment and innovative behavior has historically been centered in the field of architecture, with a focus on workspace design (Elsbach and Bechky, 2007) [

86]. However, in recent years, this topic has gained recognition and attention from sociological research as well. The existing insights drawn from the literature above offer valuable conclusions about the nexus between innovation and the physical environment. First, The physical environment should be tailored to match the various stages of the innovation process(Haner,2005[

54]; Pittaway et al.,2019[

87]). For instance, natural environments have been shown to notably impact the preparatory and incubation stages of innovation (Plambech & Konijnendijk, 2015) [

69]. Second, Architects should design physical environments with different preferred attributes (personalized or communal) depending on the type of work being done. Third, communication and collaboration are essential drivers of innovation within organizations, and the design of physical spaces can significantly influence the occurrence and effectiveness of these interactions(Sailer,2011)[

76].

While there is a wealth of literature exploring the impact of physical space on communicative innovation is abundant within the field of architecture, yet research oriented towards the processes or outcomes of innovative production remains concentrated in the field of management. Public organizational space inevitably has a subtle impact on the organizational level, which has only been theorized in a few literatures in terms of the symbolic significance of physical space in combination with organizational culture (de Vaujany & Mitev, 2013) [

81], and there is a lack of quantitative research. However, the "behavioral evidence" (Schneider et al., 2013) [

36] characteristic of organizational climate provides a theoretical basis for quantitative research on organizational culture and physical space, and it is worthwhile for scholars to explore the association between climate characteristics and physical space in terms of innovative behavior.

This paper offers several contributions. First, we review the literature on the physical environment and organizational climate in organizational studies and propose a ternary framework to guide the analysis of the linkages between sustainable innovation, physical environment, and climate environment. Second, we inductively propose four elements (communality, personalization, comfort, healthiness) of the physical environment that affect organizational operations to better review the literature on physical environment research on innovation. Third, based on the four stages of the innovation process, the hypothesis of the mechanism of influence of the physical environment and innovation climate on innovation is proposed. Fourth, we integrate research on the physical environment and innovation climate using organizational culture as a hub. Finally, we propose two directions for future research, hoping to provide some reference value for future research on the integrated environment of sustainable innovation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.P. and R.J.; methodology, R.J.; validation, L.P., R.J..; data curation, R.J.; writing—original draft preparation, J.R.; writing—review and editing, L.P.; visualization, R.J.; supervision, L.P.; project administration, L.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript and contributed equally to this work.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 51978294.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Styhre A, Sundgren M. Managing Creativity in Organizations[J]. Critique and practices, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Andriopoulos C. Determinants of organisational creativity: a literature review[J]. Management decision, 2001,39(10):834-841. [CrossRef]

- Kallio T J, Kallio K, Blomberg A J. Physical space, culture and organisational creativity – a longitudinal study[J]. Facilities, 2015,33(5/6):389-411.

- Ahmed P K. Culture and climate for innovation[J]. European journal of innovation management, 1998,1(1):30-43. [CrossRef]

- Chan D. Functional Relations Among Constructs in the Same Content Domain at Different Levels of Analysis: A Typology of Composition Models[J]. Journal of applied psychology, 1998,83(2):234-246. [CrossRef]

- Schneider B, Salvaggio A N, Subirats M. Climate strength: a new direction for climate research.[J]. Journal of Applied Psychology, 2002,87(2):220-229. [CrossRef]

- Vilnai-Yavetz I, Rafaeli A, Yaacov C S. Instrumentality, Aesthetics, and Symbolism of Office Design[J]. Environment and behavior, 2005,37(4):533-551. [CrossRef]

- SCOTT S G, BRUCE R A. Determinants of Innovative Behavior: A Path Model of Individual Innovation in the Workplace[J]. Academy of Management Journal, 1994,3(37):580-607.

- Teresa M. Amabile R C H C. Assessing the Work Environment for Creativity[J]. The Academy of Management Journal, 1996.

- WOOD R, BANDURA A. Social Cognitive Theory of Organizational Management[J]. Academy of management Review, 1989,3(14):361-384.

- Mumford M D, Gustafson S B. Creativity syndrome: Integration, application, and innovation[J]. Psychological bulletin, 1998,103(1):27.

- Kanter R M. Three tiers for innovation research[J]. Communication Research, 1988,15(5):509-523.

- Giles-Corti B, Donovan R J. The relative influence of individual, social and physical environment determinants of physical activity[J]. Social Science & Medicine, 2002,54(12):1793-1812. [CrossRef]

- Morton K L, Atkin A J, Corder K, et al. The school environment and adolescent physical activity and sedentary behaviour: a mixed-studies systematic review[J]. Obes Rev, 2016,17(2):142-158. [CrossRef]

- Stephenson K, Kuismin A, Putnam L, et al. Process studies of organizational space[J]. Academy of Management Annals, 2020,14(2):797-827.

- Repetti R L. Individual and common components of the social environment at work and psychological well-being.[J]. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1987,52(4):710.

- BROWN G, LAWRENCE T B, ROBINSON S L. Territoriality in organizations[J]. Academy of Management Review, 2005,30(3):577-594.

- Orlikowski W J. The sociomateriality of organisational life: considering technology in management research[J]. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 2010,34(1):125-141. [CrossRef]

- Hall E T. The Hidden Dimension[M]. Anchor, 1966.

- Blomberg A J, Kallio T J. A review of the physical context of creativity: A three-dimensional framework for investigating the physical context of creativity[J]. International Journal of Management Reviews, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Allen T J. Managing the Flow of Technology[M]. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1977.

- Sundstrom E, Sundstrom M G. Work places: The psychology of the physical environment in offices and factories[M]. CUP Archive, 1986.

- Hatch M J. Physical barriers, task characteristics, and interaction activity in research and development firms[J]. Administrative Science Quarterly, 1987,32:387-399.

- Jia L, Hirt E R, Karpen S C. Lessons from a Faraway land: The effect of spatial distance on creative cognition[J]. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2009,45(5):1127-1131. [CrossRef]

- Wineman J D, Kabo F W, Davis G F. Spatial and Social Networks in Organizational Innovation[J]. Environment and Behavior, 2009,41(3):427-442. [CrossRef]

- Salazar Miranda A, Claudel M. Spatial proximity matters: A study on collaboration[J]. PLOS ONE, 2021,16(12):e259965. [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth R A, Simpson L, Cassell D. Effects of three colors in an office interior on mood and performance[J]. Perceptual and motor skills, 1993,76(1):235-241.

- Jiang B, Xu W, Ji W, et al. Impacts of nature and built acoustic-visual environments on human’s multidimensional mood states: A cross-continent experiment[J]. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 2021,77:101659. [CrossRef]

- Ko W H, Schiavon S, Zhang H, et al. The impact of a view from a window on thermal comfort, emotion, and cognitive performance[J]. Building and environment, 2020,175:106779. [CrossRef]

- Khoshbakht M, Baird G, Rasheed E O. The influence of work group size and space sharing on the perceived productivity, overall comfort and health of occupants in commercial and academic buildings[J]. Indoor and Built Environment, 2021,30(5):692-710. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang D, Wang T, Gan V J L, et al. Supervised learning-based assessment of office layout satisfaction in academic buildings[J]. Building and Environment, 2022,216:109032. [CrossRef]

- Candido C, Thomas L, Haddad S, et al. Designing activity-based workspaces: satisfaction, productivity and physical activity[J]. Building research and information : the international journal of research, development and demonstration, 2019,47(3):275-289. [CrossRef]

- James L R, Choi C C, Ko C E, et al. Organizational and psychological climate: A review of theory and research[J]. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 2008,17(1):5-32. [CrossRef]

- Sleutel M R. Climate, Culture, Context, or Work Environment? Organizational Factors That Influence Nursing Practice[J]. The Journal of nursing administration, 2000,30(2):53-58. [CrossRef]

- ANDERSON N R, WEST M A. Measuring climate for work group innovation: development and validation of the team climate inventory[J]. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 1998,3(19):235-258.

- Schneider B, Ehrhart M G, Macey W H. Organizational Climate and Culture[J]. Annual review of psychology, 2013,64(9):361-388. [CrossRef]

- Dul J. Human factors in business: creating people-centric systems[J]. RSM Discovery-Management Knowledge, 2011,5(1):4-7.

- Toker U, Gray D O. Innovation spaces: Workspace planning and innovation in U.S. university research centers[J]. Research Policy, 2008,37(2):309-329. [CrossRef]

- Wagner C S, Roessner J D, Bobb K, et al. Approaches to understanding and measuring interdisciplinary scientific research (IDR): A review of the literature[J]. Journal of Informetrics, 2011,5(1):14-26. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Ji M, Deng Q, et al. Physical Connectivity as Enabler of Unexpected Encounters With Information in Campus Development: A Case Study of South China University of Technology[J]. Frontiers in Psychology, 2021,12. [CrossRef]

- Rafaeli A, Vilnai-Yavetz I. Emotion as a connection of physical artefacts and organizations[J]. Organization science, 2004,6(15):671-686.

- McCOY J M. Linking the Physical Work Environment to Creative Context[J]. The Journal of creative behavior, 2005,39(3):167-189. [CrossRef]

- Moultrie J, Nilsson M, Dissel M, et al. Innovation Spaces: Towards a Framework for Understanding the Role of the Physical Environment in Innovation[J]. Creativity and Innovation Management, 2007,16(1):53-65. [CrossRef]

- Oksanen K, Ståhle P. Physical environment as a source for innovation: investigating the attributes of innovative space[J]. Journal of Knowledge Management, 2013,17(6):815-827. [CrossRef]

- Bouncken R, Aslam M M. Understanding knowledge exchange processes among diverse users of coworking-spaces[J]. Journal of Knowledge Management, 2019,23(10):2067-2085. [CrossRef]

- Kabo F W, Cotton-Nessler N, Hwang Y, et al. Proximity effects on the dynamics and outcomes of scientific collaborations[J]. Research Policy, 2014,43(9):1469-1485. [CrossRef]

- Toker U, Gray D O. Innovation spaces: Workspace planning and innovation in U.S. university research centers[J]. Research Policy, 2008,37(2):309-329. [CrossRef]

- Sevtsuk A, Chancey B, Basu R, et al. Spatial structure of workplace and communication between colleagues: A study of E-mail exchange and spatial relatedness on the MIT campus[J]. Social Networks, 2022,70:295-305. [CrossRef]

- Hua Y, Loftness V, Kraut R, et al. Workplace Collaborative Space Layout Typology and Occupant Perception of Collaboration Environment[J]. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 2010,37(3):429-448. [CrossRef]

- Ying H, Loftness V, Heerwagen J H, et al. Relationship Between Workplace Spatial Settings and Occupant-Perceived Support for Collaboration[J]. Environment and Behavior, 2011,43(6):807-826. [CrossRef]

- Yacoub G, Haefliger S. Coworking Spaces and Collaborative Practices[J]. ORGANIZATION, 2022.DOI:13505084221074037.

- Xia B, Wu K, Guo P, et al. Multidisciplinary Innovation Adaptability of Campus Spatial Organization: From a Network Perspective[J]. SAGE Open, 2022,12(1):1999380497. [CrossRef]

- KELLY T. The art of innovation[M]. Profile Business, 2002.

- Haner U. Spaces for Creativity and Innovation in Two Established Organizations[J]. Creativity and innovation management, 2005,14(3):288-298. [CrossRef]

- Crawford R. Office space: Australian advertising agencies in the twentieth century[J]. Journal of Management History, 2018,4(24):396-413. [CrossRef]

- Martens Y. Creative workplace: instrumental and symbolic support for creativity[J]. Facilities, 2011,29(1/2):63-79. [CrossRef]

- McCoy J M, Evans G W. The Potential Role of the Physical Environment in Fostering Creativity[J]. Creativity research journal, 2002,14(3-4):409-426. [CrossRef]

- Ceylan C, Dul J, Aytac S. Can the office environment stimulate a manager's creativity?[J]. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing, 2008,18(6):589-602. [CrossRef]

- Lukersmith S, Burgess-Limerick R. The perceived importance and the presence of creative potential in the health professional's work environment[J]. Ergonomics, 2013,56(6):922-934. [CrossRef]

- Dul J, Ceylan C. Work environments for employee creativity[J]. Ergonomics, 2011,54(1):12-20.

- Stryker J B, Santoro M D, Farris G F. Creating Collaboration Opportunity: Designing the Physical Workplace to Promote High-Tech Team Communication[J]. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 2012,59(4):609-620. [CrossRef]

- Bernstein E S, Turban S. The impact of the 'open' workspace on human collaboration[J]. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 2018,373(1753). [CrossRef]

- Peponis J, Bafna S, Bajaj R, et al. Designing Space to Support Knowledge Work[J]. Environment and behavior, 2007,39(6):815-840. [CrossRef]

- Motalebi G, Parvaneh A. The effect of physical work environment on creativity among artists’ residencies[J]. Facilities, 2021,39(13/14):911-923. [CrossRef]

- Kristensen T. The Physical Context of Creativity[J]. Creativity and Innovation Management, 2004,13(2):89-96. [CrossRef]

- Clements-Croome D E. Creating the Productive Workplace[M]. Oxford, England: Taylor & Francis, 2006.

- van den Bogerd N, Dijkstra S C, Koole S L, et al. Greening the room: A quasi-experimental study on the presence of potted plants in study rooms on mood, cognitive performance, and perceived environmental quality among university students[J]. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 2021,73:101557. [CrossRef]

- SHIBATA S, SUZUKI N. Effects of an indoor plant on creative task performance and mood[J]. Scandinavian journal of psychology, 2004,45(5):373-381. [CrossRef]

- Plambech T, Konijnendijk Van Den Bosch C C. The impact of nature on creativity – A study among Danish creative professionals[J]. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 2015,14(2):255-263. [CrossRef]

- Ko W H, Schiavon S, Zhang H, et al. The impact of a view from a window on thermal comfort, emotion, and cognitive performance[J]. Building and Environment, 2020,175:106779. [CrossRef]

- Atchley R A, Strayer D L, Atchley P. Creativity in the Wild: Improving Creative Reasoning through Immersion in Natural Settings[J]. PLoS ONE, 2012,7(12):e51474. [CrossRef]

- Yeh C, Hung S, Chang C. The influence of natural environments on creativity[J]. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 2022,13. [CrossRef]

- Chulvi V, Agost M J, Felip F, et al. Natural elements in the designer's work environment influence the creativity of their results[J]. Journal of Building Engineering, 2020,28:101033. [CrossRef]

- Steidle A, Werth L. Freedom from constraints: Darkness and dim illumination promote creativity[J]. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 2013,35:67-80. [CrossRef]

- Fang L, Wyon D P, Clausen G, et al. Impact of indoor air temperature and humidity in an office on perceived air quality, SBS symptoms and performance[J]. Indoor Air, 2004,14 Suppl 7:74-81. [CrossRef]

- Sailer K. Creativity as social and spatial process[J]. Facilities (Bradford, West Yorkshire, England), 2011,29(1/2):6-18. [CrossRef]

- Amabile T M, Conti R, Coon H, et al. Assessing the work environment for creativity[J]. Academy of management journal, 1996,39(5):1154-1184.

- Newman A, Round H, Wang S, et al. Innovation climate: A systematic review of the literature and agenda for future research[J]. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 2019,93(1):73-109. [CrossRef]

- TESLUK P E, FARR J L, KLEIN S R. Influences of Organizational Culture and Climate on Individual Creativity[J]. The Journal of creative behavior, 1997,31(1):27-41. [CrossRef]

- Tomás T N. Manual de pronunciación española[M]. Junta para ampliación de estudios e investigaciones científicas, Centro de …, 1926.

- de Vaujany F, Mitev N. Introduction: Space in organizations and sociomateriality[M]// Materiality and space: Organizations, artefacts and practices. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013:1-21.

- Panuwatwanich K, Stewart R A, Mohamed S. The role of climate for innovation in enhancing business performance[J]. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 2008,15(5):407-422. [CrossRef]

- Munir R, Beh L. Measuring and enhancing organisational creative climate, knowledge sharing, and innovative work behavior in startups development[J]. The Bottom line (New York, N.Y.), 2019,32(4):269-289. [CrossRef]

- Ashkanasy N M, Ayoko O B, Jehn K A. Understanding the physical environment of work and employee behavior: An affective events perspective[J]. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2014,35(8):1169-1184. [CrossRef]

- Brown A D, Humphreys M. Organizational identity and place: a discursive exploration of hegemony and resistance[J]. Journal of management studies, 2005,43(2):231-258.

- Elsbach K D, Bechky B A. It's More than a Desk: Working Smarter through Leveraged Office Design[J]. California management review, 2007,49(2):80-101. [CrossRef]

- Pittaway L, Aissaoui R, Ferrier M, et al. University spaces for entrepreneurship: a process model[J]. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 2019,26(5):911-936. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).