Submitted:

07 September 2023

Posted:

07 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Edible Coatings’ Contextualization

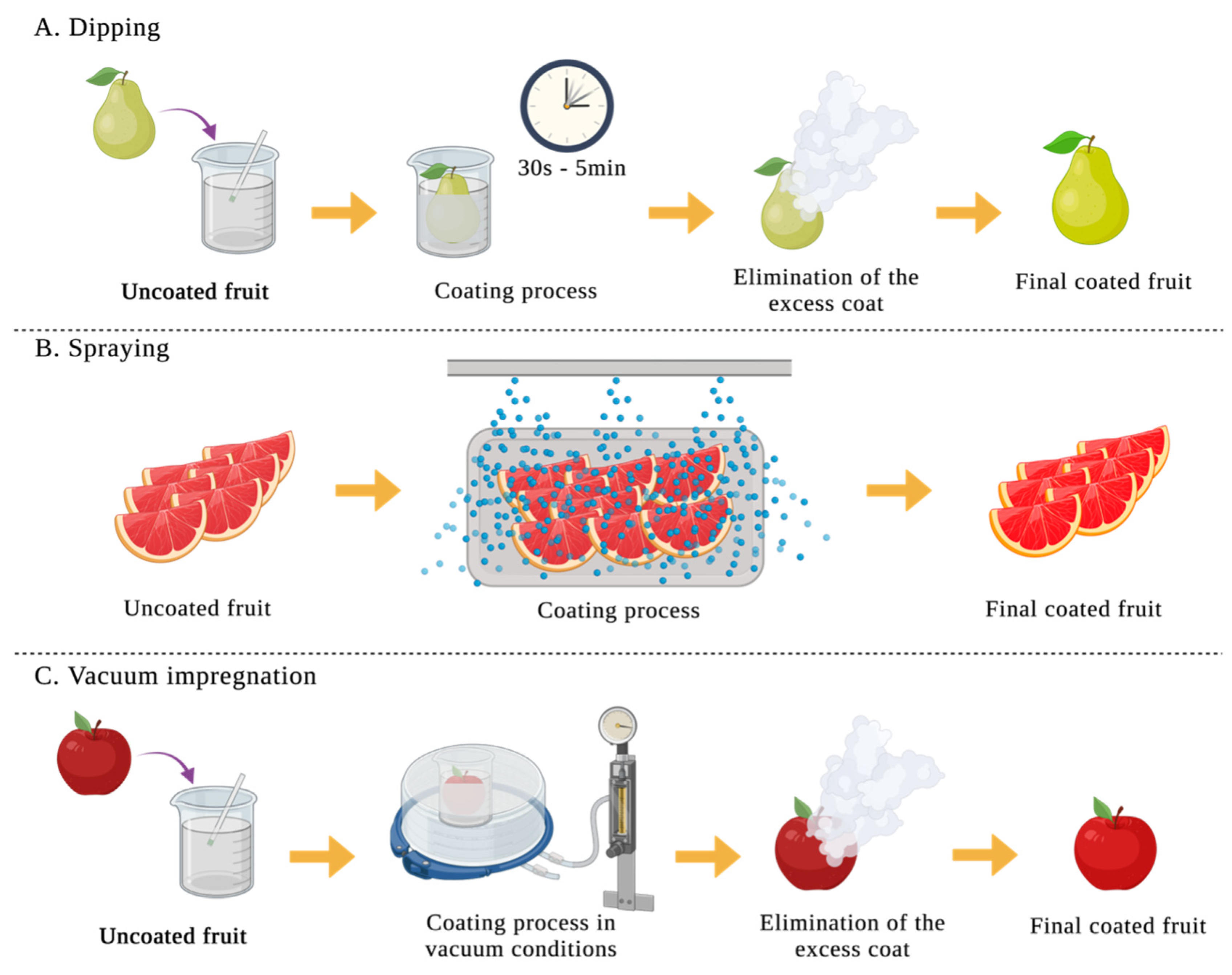

2.1. Film Formation and Application of Coat

2.2. Principle Macromolecules Used for the Edible Coating Formulation

2.2.1. Polysaccharides

2.2.2. Proteins

2.2.3. Lipids

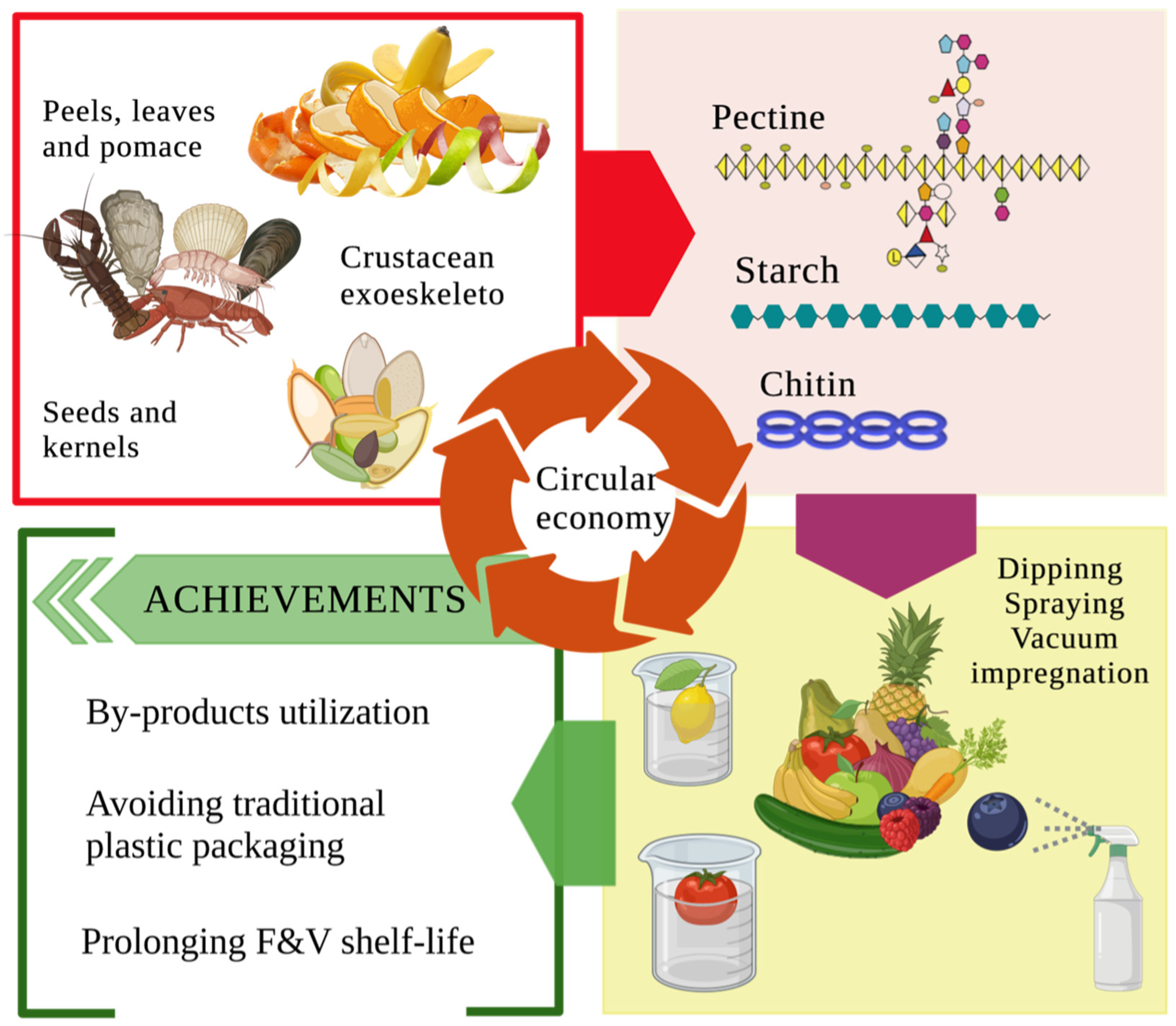

3. Food By-Products as Materials for the Edible Coating Formation

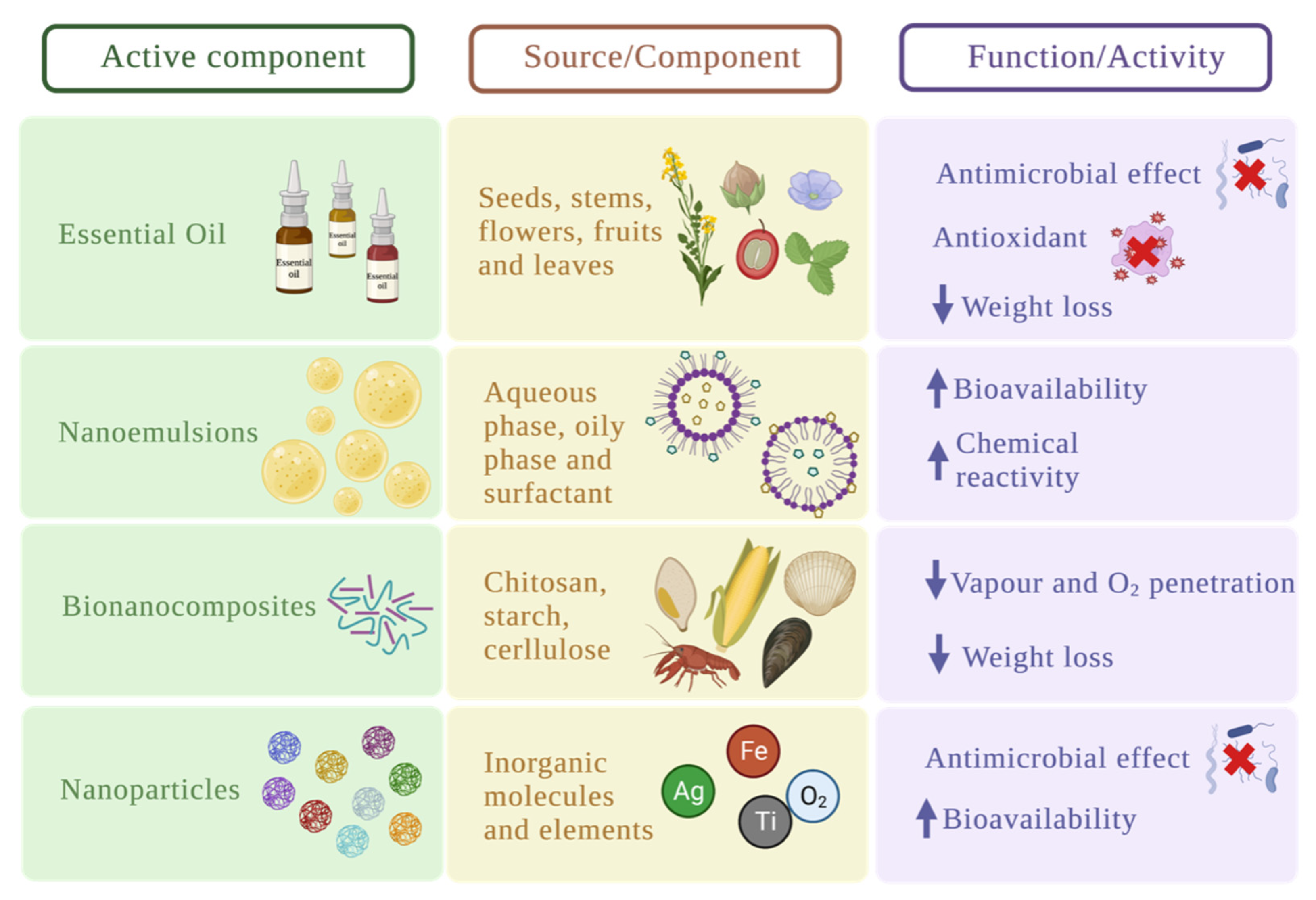

4. Improvement of the Physicochemical and Functional Characteristics of the Coatings

4.1. Essential Oils

4.2. Nanoemulsions

4.3. Bio-Nanocomposites

4.4. Inorganic Nanoparticles

5. Application of Edible Coatings in Fruits and Vegetables

5.1. Current Application of Edible Coatings Applied in Fruits and Vegetables

5.2. Effects of Edible Coatings in the Sensory Characteristics

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Suhag, R.; Kumar, N.; Petkoska, A.T.; Upadhyay, A. Film Formation and Deposition Methods of Edible Coating on Food Products: A Review. Food Res. Int. 2020, 136. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, V.; Sharma, R. Chitosan Nanoemulsions as Advanced Edible Coatings for Fruits and Vegetables: Composition, Fabrication and Developments in Last Decade. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 152, 154–170. [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Chen, W.; Li, C.; Aziz, T.; Cui, H.; Lin, L. Topical Advances of Edible Coating Based on the Nanoemulsions Encapsulated with Plant Essential Oils for Foodborne Pathogen Control. Food Control 2023, 145. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, J.; Dong, M.; Zhang, H.; Li, L.; Wang, L. Food Spoilage, Bioactive Food Fresh-Keeping Films and Functional Edible Coatings: Research Status, Existing Problems and Development Trend. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 119, 122–132. [CrossRef]

- Salgado, P.R.; Ortiz, C.M.; Musso, Y.S.; Di Giorgio, L.; Mauri, A.N. Edible Films and Coatings Containing Bioactives. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2015, 5, 86–92. [CrossRef]

- Rohasmizah, H.; Azizah, M. Pectin-Based Edible Coatings and Nanoemulsion for the Preservation of Fruits and Vegetables: A Review. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2, 100221. [CrossRef]

- Pratap Singh, D.; Packirisamy, G. Biopolymer Based Edible Coating for Enhancing the Shelf Life of Horticulture Products. Food Chem. Mol. Sci. 2022, 4, 100085. [CrossRef]

- Sousa-Gallagher, M.J.; Tank, A.; Sousa, R. Emerging Technologies to Extend the Shelf Life and Stability of Fruits and Vegetables. Stab. Shelf Life Food 2016, 399–430. [CrossRef]

- Yousuf, B.; Qadri, O.S.; Srivastava, A.K. Recent Developments in Shelf-Life Extension of Fresh-Cut Fruits and Vegetables by Application of Different Edible Coatings: A Review. LWT 2018, 89, 198–209. [CrossRef]

- Alegbeleye, O.; Odeyemi, O.A.; Strateva, M.; Stratev, D. Microbial Spoilage of Vegetables, Fruits and Cereals. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2, 100122. [CrossRef]

- Oyom, W.; Zhang, Z.; Bi, Y.; Tahergorabi, R. Application of Starch-Based Coatings Incorporated with Antimicrobial Agents for Preservation of Fruits and Vegetables: A Review. Prog. Org. Coatings 2022, 166, 106800. [CrossRef]

- Facchini, F.; Silvestri, B.; Digiesi, S.; Lucchese, A. Agri-Food Loss and Waste Management: Win-Win Strategies for Edible Discarded Fruits and Vegetables Sustainable Reuse. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 83, 103235. [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.; Barua, M.K. Modeling the Key Factors Leading to Post-Harvest Loss and Waste of Fruits and Vegetables in the Agri-Fresh Produce Supply Chain. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 198, 106936. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, V.K.; Islam, R.U.; Shams, R.; Dar, A.H. A Comprehensive Review on the Application of Essential Oils as Bioactive Compounds in Nano-Emulsion Based Edible Coatings of Fruits and Vegetables. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2, 100042. [CrossRef]

- Le, K.H.; Nguyen, M.D.B.; Tran, L.D.; Nguyen Thi, H.P.; Tran, C. Van; Tran, K. Van; Nguyen Thi, H.P.; Dinh Thi, N.; Yoon, Y.S.; Nguyen, D.D.; et al. A Novel Antimicrobial ZnO Nanoparticles-Added Polysaccharide Edible Coating for the Preservation of Postharvest Avocado under Ambient Conditions. Prog. Org. Coatings 2021, 158. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, B.; Chatha, S.A.S.; Hussain, A.I.; Zia, K.M.; Akhtar, N. Recent Advances on Polysaccharides, Lipids and Protein Based Edible Films and Coatings: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 109, 1095–1107. [CrossRef]

- Nair, M.S.; Tomar, M.; Punia, S.; Kukula-Koch, W.; Kumar, M. Enhancing the Functionality of Chitosan- and Alginate-Based Active Edible Coatings/Films for the Preservation of Fruits and Vegetables: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 304–320. [CrossRef]

- Romanazzi, G.; Moumni, M. Chitosan and Other Edible Coatings to Extend Shelf Life, Manage Postharvest Decay, and Reduce Loss and Waste of Fresh Fruits and Vegetables. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2022, 78, 102834. [CrossRef]

- Chiralt, A.; Menzel, C.; Hernandez-García, E.; Collazo, S.; Gonzalez-Martinez, C. Use of By-Products in Edible Coatings and Biodegradable Packaging Materials for Food Preservation. Sustain. Food Syst. Sovereignty, Waste, Nutr. Bioavailab. 2020, 101–127. [CrossRef]

- Rohasmizah, H.; Azizah, M. Pectin-Based Edible Coatings and Nanoemulsion for the Preservation of Fruits and Vegetables: A Review. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2, 100221. [CrossRef]

- Panahirad, S.; Dadpour, M.; Peighambardoust, S.H.; Soltanzadeh, M.; Gullón, B.; Alirezalu, K.; Lorenzo, J.M. Applications of Carboxymethyl Cellulose- and Pectin-Based Active Edible Coatings in Preservation of Fruits and Vegetables: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 110, 663–673. [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi, M.; Pitirollo, O.; Ornaghi, P.; Corradini, C.; Cavazza, A. Valorization of Agro-Industrial Byproducts: Extraction and Analytical Characterization of Valuable Compounds for Potential Edible Active Packaging Formulation. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2022, 33, 100900. [CrossRef]

- Karimi Sani, I.; Masoudpour-Behabadi, M.; Alizadeh Sani, M.; Motalebinejad, H.; Juma, A.S.M.; Asdagh, A.; Eghbaljoo, H.; Khodaei, S.M.; Rhim, J.W.; Mohammadi, F. Value-Added Utilization of Fruit and Vegetable Processing by-Products for the Manufacture of Biodegradable Food Packaging Films. Food Chem. 2023, 405, 134964. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zhang, W.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Pu, Y.; Cao, J.; Jiang, W. Applications of Plant-Derived Food by-Products to Maintain Quality of Postharvest Fruits and Vegetables. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 1105–1119. [CrossRef]

- Torres-León, C.; Vicente, A.A.; Flores-López, M.L.; Rojas, R.; Serna-Cock, L.; Alvarez-Pérez, O.B.; Aguilar, C.N. Edible Films and Coatings Based on Mango (Var. Ataulfo) by-Products to Improve Gas Transfer Rate of Peach. LWT 2018, 97, 624–631. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Chen, C.; Gan, Z.; Chen, J.; Wan, C. (Craig) Loquat Leaf Extract and Alginate Based Green Composite Edible Coating for Preserving the Postharvest Quality of Nanfeng Tangerines. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2022, 27, 100674. [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Veloz, L.M.; Calderón-Santoyo, M.; Carvajal-Millan, E.; Martínez-Robinson, K.; Ragazzo-Sánchez, J.A. Artocarpus Heterophyllus Lam. Leaf Extracts Added to Pectin-Based Edible Coating for Alternaria Sp. Control in Tomato. LWT 2022, 156, 113022. [CrossRef]

- Rivera Calo, J.; Crandall, P.G.; O’bryan, C.A.; Ricke, S.C. Essential Oils as Antimicrobials in Food Systems e A Review. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-González, L.; Vargas, M.; González-Martínez, C.; Chiralt, A.; Cháfer, M. Use of Essential Oils in Bioactive Edible Coatings: A Review. Food Eng. Rev. 2011, 3, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Donsì, F.; Annunziata, M.; Sessa, M.; Ferrari, G. Nanoencapsulation of Essential Oils to Enhance Their Antimicrobial Activity in Foods. [CrossRef]

- Carpena, M.; Nuñez-Estevez, B.; Soria-Lopez, A.; Garcia-Oliveira, P.; Prieto, M.A. Essential Oils and Their Application on Active Packaging Systems: A Review. Resources 2021, 10, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Wang, H.; Xu, X.; Lu, X.; Song, X.; Zhou, G. Effects of Nanoemulsion-Based Edible Coatings with Composite Mixture of Rosemary Extract and ε-Poly-l-Lysine on the Shelf Life of Ready-to-Eat Carbonado Chicken. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 102, 105576. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Mcclements, D.J. Nanoemulsions: An Emerging Platform for Increasing the Efficacy of Nutraceuticals in Foods. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Aloui, H.; Khwaldia, K. Natural Antimicrobial Edible Coatings for Microbial Safety and Food Quality Enhancement. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2016, 15, 1080–1103. [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, N.; Ranjan, S.; Gandhi, M. Nanoemulsions in Food: Market Demand. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2019, 17, 1003–1009. [CrossRef]

- Jafarzadeh, S.; Mohammadi Nafchi, A.; Salehabadi, A.; Oladzad-abbasabadi, N.; Jafari, S.M. Application of Bio-Nanocomposite Films and Edible Coatings for Extending the Shelf Life of Fresh Fruits and Vegetables. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 291. [CrossRef]

- Jayakumar, A.; Radoor, S.; Kim, J.T.; Rhim, J.W.; Nandi, D.; Parameswaranpillai, J.; Siengchin, S. Recent Innovations in Bionanocomposites-Based Food Packaging Films – A Comprehensive Review. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2022, 33, 100877. [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Yan, M.; Wu, S.; Ge, X.; Liu, S.; Du, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Mao, Y. Chitosan Nanoparticles Embedded with Curcumin and Its Application in Pork Antioxidant Edible Coating. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 204, 410–418. [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Oh, S.W. Enhancing Safety and Quality of Shrimp by Nanoparticles of Sodium Alginate-Based Edible Coating Containing Grapefruit Seed Extract. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 189, 84–90. [CrossRef]

- Sucheta; Chaturvedi, K.; Sharma, N.; Yadav, S.K. Composite Edible Coatings from Commercial Pectin, Corn Flour and Beetroot Powder Minimize Post-Harvest Decay, Reduces Ripening and Improves Sensory Liking of Tomatoes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 133, 284–293. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Garcia, I.; Cruz-Valenzuela, M.R.; Silva-Espinoza, B.A.; Gonzalez-Aguilar, G.A.; Moctezuma, E.; Gutierrez-Pacheco, M.M.; Tapia-Rodriguez, M.R.; Ortega-Ramirez, L.A.; Ayala-Zavala, J.F. Oregano (Lippia Graveolens) Essential Oil Added within Pectin Edible Coatings Prevents Fungal Decay and Increases the Antioxidant Capacity of Treated Tomatoes. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 3772–3778. [CrossRef]

- Abdel Aziz, M.S.; Salama, H.E. Development of Alginate-Based Edible Coatings of Optimized UV-Barrier Properties by Response Surface Methodology for Food Packaging Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 212, 294–302. [CrossRef]

- Khodaei, D.; Hamidi-Esfahani, Z.; Rahmati, E. Effect of Edible Coatings on the Shelf-Life of Fresh Strawberries: A Comparative Study Using TOPSIS-Shannon Entropy Method. NFS J. 2021, 23, 17–23. [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.; Gao, C.; Liu, X.; Zhang, N.; Xu, T.; Feng, X.; Yang, Y.; Shen, X.; Tang, X. Improvement of Storage Quality of Strawberries by Pullulan Coatings Incorporated with Cinnamon Essential Oil Nanoemulsion. LWT 2020, 122, 109054. [CrossRef]

- Zam, W. Effect of Alginate and Chitosan Edible Coating Enriched with Olive Leaves Extract on the Shelf Life of Sweet Cherries (Prunus Avium L.). J. Food Qual. 2019, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Eshghi, S.; Karimi, R.; Shiri, · Azam; Karami, · Mostafa; Moradi, M. Effects of Polysaccharide-Based Coatings on Postharvest Storage Life of Grape: Measuring the Changes in Nutritional, Antioxidant and Phenolic Compounds. 2022, 16, 1159–1170. [CrossRef]

- Rossi Marquez, G.; Di Pierro, P.; Mariniello, L.; Esposito, M.; Giosafatto, C.V.L.; Porta, R. Fresh-Cut Fruit and Vegetable Coatings by Transglutaminase-Crosslinked Whey Protein/Pectin Edible Films. LWT 2017, 75, 124–130. [CrossRef]

- Galus, S.; Mikus, M.; Ciurzyńska, A.; Domian, E.; Kowalska, J.; Marzec, A.; Kowalska, H. The Effect of Whey Protein-Based Edible Coatings Incorporated with Lemon and Lemongrass Essential Oils on the Quality Attributes of Fresh-Cut Pears during Storage. Coatings 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Grosso, A.L.; Asensio, C.M.; Grosso, N.R.; Nepote, V. Increase of Walnuts’ Shelf Life Using a Walnut Flour Protein-Based Edible Coating. LWT 2020, 118, 108712. [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, P.; Khan, S.A.K.U.; Siddiqua, M.; Sultana, S. Effect of Guava Leaf and Lemon Extracts on Postharvest Quality and Shelf Life of Banana Cv. Sabri (Musa Sapientum L.). J. Bangladesh Agric. Univ. 2018, 16, 337–342. [CrossRef]

- Basaglia, R.R.; Pizato, S.; Santiago, N.G.; Maciel de Almeida, M.M.; Pinedo, R.A.; Cortez-Vega, W.R. Effect of Edible Chitosan and Cinnamon Essential Oil Coatings on the Shelf Life of Minimally Processed Pineapple (Smooth Cayenne). Food Biosci. 2021, 41. [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Vishakha, K.; Banerjee, S.; Mondal, S.; Ganguli, A. Sodium Alginate-Based Edible Coating Containing Nanoemulsion of Citrus Sinensis Essential Oil Eradicates Planktonic and Sessile Cells of Food-Borne Pathogens and Increased Quality Attributes of Tomatoes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 162, 1770–1779. [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, S.; Gull, A.; Wani, S.M.; Ganaie, T.A.; Masoodi, F.A.; Bashir, K.; Malik, A.R.; Dar, B.N. Improving the Shelf Life of Fresh Cut Kiwi Using Nanoemulsion Coatings with Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Agents. Food Biosci. 2021, 41, 101015. [CrossRef]

- Alves, M.M.; Gonçalves, M.P.; Rocha, C.M.R. Effect of Ferulic Acid on the Performance of Soy Protein Isolate-Based Edible Coatings Applied to Fresh-Cut Apples. LWT 2017, 80, 409–415. [CrossRef]

- Ghidelli, C.; Mateos, M.; Rojas-Argudo, C.; Pérez-Gago, M.B. Extending the Shelf Life of Fresh-Cut Eggplant with a Soy Protein–Cysteine Based Edible Coating and Modified Atmosphere Packaging. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2014, 95, 81–87. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Saini, C.S. Edible Composite Bi-Layer Coating Based on Whey Protein Isolate, Xanthan Gum and Clove Oil for Prolonging Shelf Life of Tomatoes. Meas. Food 2021, 2, 100005. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Wu, G.; Liu, C.; Li, D.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, X. Edible Coating Based on Whey Protein Isolate Nanofibrils for Antioxidation and Inhibition of Product Browning. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 79, 179–188. [CrossRef]

- Mendy, T.K.; Misran, A.; Mahmud, T.M.M.; Ismail, S.I. Application of Aloe Vera Coating Delays Ripening and Extend the Shelf Life of Papaya Fruit. Sci. Hortic. (Amsterdam). 2019, 246, 769–776. [CrossRef]

- Poverenov, E.; Zaitsev, Y.; Arnon, H.; Granit, R.; Alkalai-Tuvia, S.; Perzelan, Y.; Weinberg, T.; Fallik, E. Effects of a Composite Chitosan–Gelatin Edible Coating on Postharvest Quality and Storability of Red Bell Peppers. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2014, 96, 106–109. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Gonzalez, L.; Pastor, C.; Vargas, M.; Chiralt, A.; Gonzalez-Martinez, C.; Chafer, M. Effect of Hydroxypropylmethylcellulose and Chitosan Coatings with and without Bergamot Essential Oil on Quality and Safety of Cold-Stored Grapes. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2011, 60, 57–63. [CrossRef]

- Saberi, B.; Golding, J.B.; Marques, J.R.; Pristijono, P.; Chockchaisawasdee, S.; Scarlett, C.J.; Stathopoulos, C.E. Application of Biocomposite Edible Coatings Based on Pea Starch and Guar Gum on Quality, Storability and Shelf Life of ‘Valencia’ Oranges. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2018, 137, 9–20. [CrossRef]

- Nawab, A.; Alam, F.; Hasnain, A. Mango Kernel Starch as a Novel Edible Coating for Enhancing Shelf- Life of Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum) Fruit. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 103, 581–586. [CrossRef]

- Tesfay, S.Z.; Magwaza, L.S. Evaluating the Efficacy of Moringa Leaf Extract, Chitosan and Carboxymethyl Cellulose as Edible Coatings for Enhancing Quality and Extending Postharvest Life of Avocado (Persea Americana Mill.) Fruit. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2017, 11, 40–48. [CrossRef]

- Chong, K.Y.; Brooks, M.S.L. Development of Pea Protein-Based Films and Coatings with Haskap Leaf Extracts. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2, 100102. [CrossRef]

| Edible coating | Macro-molecule | Active component | Food product | Improvement | T (ºC) |

t (days) |

RH (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alginate (3%) + Chitosan (1%) + Olive leaf extract | PS | Olive leaf extract | Cherry fruits | Retardation of maturation, Anthocyanin incrementation | 25 | 20 | 65 | [45] |

| Guava leaf extract (20%) + Lemon extract (15%) | - | Guava leaf extract + Lemon extract | Banana | Reduction of color changes, Preservation of vitamin C | NS | 14 | NS | [50] |

| Commercial pectin + corn-flour starch + beetroot powder | PS | Corn-flour starch // Corn-flower-beetroot powder | Tomatoes | Lower weight loss, Lower decay percentage, Lower respiration rate | 25 | 30 | 80-85 | [40] |

| Pectin + Oregano essential oil (36.1 mg/mL) | PS | Oregano EO | Tomatoes | Lower fungal decay, Increasement of antioxidant activity | 25 | 12 | NS | [41] |

| Whey protein pectin + pectin + transglutaminase | PR and PS | Transglutaminase | Apples, Potatoes, Carrots | Lower weight loss, Inhibition of microbial growth, Antioxidant activity preservation | 4-6 | 10 | NS | [47] |

| Glycerol + Tragacanth gum (0.6 %) | PS | Tragacanth gum | Strawberries | Reduction of the rate of deterioration in ascorbic acid, total phenolics and anthocyanins | 4 | 16 | NS | [43] |

| Glycerol + CMC (1%) | CMC | |||||||

| Glycerol +LMP (2%) | LMP | |||||||

| Glycerol + PG (4%) | PG | |||||||

| Whey protein (8%) + lemon oil (1%) | PR | Lemon oil | Pears | Reduction in color changes, Reduction in loss of hardness, Reduction in loss of polyphenols and flavonoids | 4 | 7-28 | 80 | [48] |

| Whey protein (8%) + lemon grass essential oil (0.5%) | PR | Lemongrass EO | ||||||

| Chitosan (1%) + Gum ghatti (1%) | PS | Gum gatthi | Grapes | Retention of phenolic acids content, Reduction in yeast-mold growth | 1 | 60 | 85-90 | [46] |

| Alginate + Aloe vera + ZnO-NPs | PS | Aloe vera ZnO-NPs | Tomatoes | No spoilage during the storage | RT | 16 | NS | [42] |

| PET + Chitosan (2%) + Cinnamon essential oil (0.5%) | PS | Cinnamon EO | Pineapple | Lower weight loss, Lower decrease of L*, Microbial growth retardation | 5 | 15 | NS | [51] |

| Sodium alginate + sweet orange essential oil (5%) | PS | Sweet orange EO | Tomatoes | Eradication of sessile and planktonic forms of Salmonella and Listeria, Lower weight loss | 22 | 15 | NS | [52] |

| Pullulan + cinnamon EO | PS | Cinnamon EO | Strawberry | Delay in mass loss, decay percentage and firmness | 20 | 6 | 70-75% | [44] |

| Sodium alginate (2%) + ascorbic acid (0.5%) + vanillin (1%) | PS | Ascorbic acid, Vanillin | Kiwifruit | Lower decay, Lower ascorbic acid loss | 5 | 7 | NS | [53] |

| Sodium alginate (2%) + ascorbic acid (0.5%) + vanillin (0.5%) | Lower weight loss | |||||||

| Walnut flour protein | PR | - | Walnuts | Protection against lipid deterioration, Preservation of the sensory characteristics | 40 | 84 | NS | [49] |

| Soy protein + ferulic acid | PR | Ferulic acid | Fresh-cut apple | Weight loss control, Firmness control | 10 | 7 | 50 | [54] |

| Soy protein + cysteine (1%) | PR | Cysteine | Fresh-cut eggplant | Enzymatic browning control | 8-9 | 5 | NS | [55] |

| Whey protein +. Xanthan gum + Clove oil | PR | Clove oil | Tomatoes | Improvements in firmness and color, Respiration is inhibited | 15 | 20 | 85 | [56] |

| Whey protein nanofibrils + glycerol + trehalose | PR | Glycerol and trehalose | Fresh-cut apple | Enzymatic browning control | 10 | 4 | NS | [57] |

| Whey protein nanofibrils | - | Hydrophobic and antioxidant activity | ||||||

| Aloe vera 50% gel | Gel | Aloe vera | Papaya fruit | Control disease pathogens, Delay ripening, Water loss control, Respiration rate reduction | 15 | 28 | 68-70 | [58] |

| Chitosan-gelatin | PS | - | Red bell peppers | Microbial spoilage reduction, Respiration rate maintenance, Nutritional content maintenance | 7;20 | 14 | - | [59] |

| 21 | 7 | |||||||

| 14 | 20 | |||||||

| Chitosan + HPMC + bergamot EO | PS | Bergamot EO | Grapes | Weight loss reduction, Respiration rate reduction, Firmness improvement, Antimicrobial effect | 1-2 | 22 | - | [60] |

| Pea starch + guar gum | PS | - | Oranges | Shelf-life extension, Higher perception of off flavors, Better sensory scores | 20 | 7 | 90-95 | [61] |

| Product | Subproduct | Extraction | Conditions | Compound | Formulation | Application | Product | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mango | Mango peel flour | Drying pretreatment | 60ºC; 48h | - | 1.09% MPF 0.33% Gly |

Casting | Peach | [25] |

| Mango seed kernel | Solvent extraction | EtOH 90%; 75ºC | Antioxidant compounds | 1.09% MPF 0.33% Gly 0.078 g/L EMS |

||||

| Onion | Leaves, stems, flowers | UAE | Acetone | Phenolic compounds | 1% SA 0.3 g/g Gly/SA 0.04 g/g CaCO3/ SA 5.4 g/g GDL/CaCO3 |

- | - | [22] |

| Artichoke | ||||||||

| Thistle | ||||||||

| Mango | Kernel | Solvent extraction | Sodium metabisulphite 0.16% | Amylose; amylopectin | Gly:Sorbitol 1:1 Starch 50% |

Dipping | Tomato | [62] |

| Olive leaf | Leaves | Solvent extraction | EtOH 40%; 60ºC; 120 min | Olive leaf extract | 3% SA 10% Gly 2% CaCl2 0.01g/mL Chitosan 0.02 g/mL OLE |

Dipping | Sweet cherries | [45] |

| Loquat leaf | Leaves | Reflux extraction | EtOH 50%; 196ºC | Loquat leaf extract | 10 g/L SA 0.7 g/L CA 10 g/L SE 0.5 g/L AsA 0.5 g/L PS |

Dipping | Tangerines | [26] |

| Jackfruit leaf | Leaves | MAE | EtOH:H2O 4:1; 840 W; 2min | Jackfruit leaf extract | 1.5% pectin (w/v) 30% w/w) Gly 10% (w/w) Beeswax JLE 5mg/mL |

Wounded | Tomatoes | [27] |

| Moringa leaf | Leaves | NS | - | Moringa leaf extract | MLE 2% Chitosan 0.5% CMC 0.5% |

Dipping | Avocado | [63] |

| Haskap leaf | Leaves | ATPE | Sodium phosphate 10%, EtOH 37%, H2O 53%; min5 | Haskap leaf bioactive compounds | PPC 10% 0.91% Gly 10% SPHLE/ASHLE 1.7 g CA/MA |

Filming | Grape tomatoes | [64] |

| Dipping | Bananas |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).