Submitted:

06 September 2023

Posted:

08 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Precocious puberty

- –

- central or true precocious puberty (CPP), if it is determined by an early activation of the HPG axis with the production of gonadotropins

- –

- peripheral or precocious pseudopuberty (PPP), unrelated to the production of gonadotropins.

Central precocious puberty

Peripherical precocious puberty

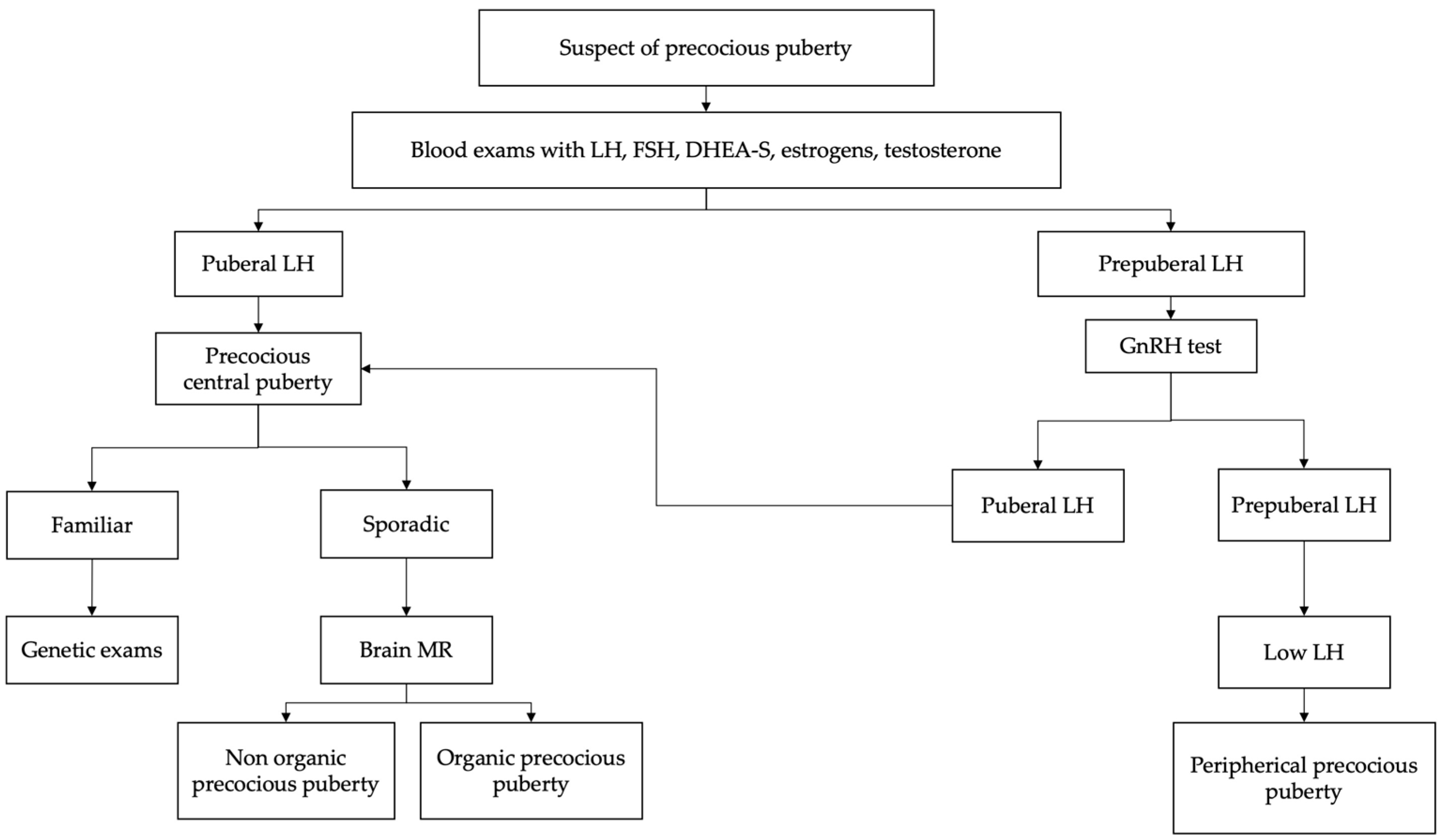

2. Diagnosis

3. Treatment

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Eugster EA. Treatment of central precocious puberty. J Endocr Soc 2019;3. [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Lora AL, Torres-Tamayo M, Zurita-Cruz JN, Aguilar-Herrera BE, Calzada-León R, Rivera-Hernández AJ, et al. Diagnosis of precocious puberty: Clinical guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of precocious puberty. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex 2020;77. [CrossRef]

- Aguirre RS, Eugster EA. Central precocious puberty: From genetics to treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2018;32. [CrossRef]

- Loomba-Albrecht LA, Styne DM. The physiology of puberty and its disorders. Pediatr Ann 2012;41. [CrossRef]

- Wood CL, Lane LC, Cheetham T. Puberty: Normal physiology (brief overview). Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019;33. [CrossRef]

- Koskenniemi JJ, Virtanen HE, Toppari J. Testicular growth and development in puberty. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2017;24. [CrossRef]

- Latronico AC, Brito VN, Carel JC. Causes, diagnosis, and treatment of central precocious puberty. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2016;4. [CrossRef]

- Klein DA, Emerick JE, Sylvester JE, Vogt KS. Disorders of Puberty: An Approach to Diagnosis and Management. Am Fam Physician 2017;96.

- Brito VN, Canton APM, Seraphim CE, Abreu AP, Macedo DB, Mendonca BB, et al. The Congenital and Acquired Mechanisms Implicated in the Etiology of Central Precocious Puberty. Endocr Rev 2023;44. [CrossRef]

- Brito VN, Spinola-Castro AM, Kochi C, Kopacek C, Da Silva PCA, Guerra-Júnior G. Central precocious puberty: Revisiting the diagnosis and therapeutic management. Arch Endocrinol Metab 2016;60. [CrossRef]

- Sultan C, Gaspari L, Maimoun L, Kalfa N, Paris F. Disorders of puberty. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2018;48. [CrossRef]

- Manotas MC, González DM, Céspedes C, Forero C, Moreno APR. Genetic and Epigenetic Control of Puberty. Sex Dev 2022;16. [CrossRef]

- Petrella C, Nenna R, Petrarca L, Tarani F, Paparella R, Mancino E, et al. Serum NGF and BDNF in Long-COVID-19 Adolescents: A Pilot Study. Diagnostics 2022;12:1162. [CrossRef]

- Prosperi S, Chiarelli F. Early and precocious puberty during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023;13. [CrossRef]

- Chioma L, Bizzarri C, Verzani M, Fava D, Salerno M, Capalbo D, et al. Sedentary lifestyle and precocious puberty in girls during the COVID-19 pandemic: an Italian experience. Endocr Connect 2022;11. [CrossRef]

- Kim EY, Lee MI. Psychosocial aspects in girls with idiopathic precocious puberty. Psychiatry Investig 2012;9. [CrossRef]

- Tremblay L, Frigon JY. Precocious puberty in adolescent girls: A biomarker of later psychosocial adjustment problems. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2005;36. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira Neto CP de, Azulay RS de S, Almeida AGFP de, Tavares M da GR, Vaz LHG, Leal IRL, et al. Differences in Puberty of Girls before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19. [CrossRef]

- Shim YS, Lee HS, Hwang JS. Genetic factors in precocious puberty. Clin Exp Pediatr 2022;65. [CrossRef]

- Tauber M, Hoybye C. Endocrine disorders in Prader-Willi syndrome: a model to understand and treat hypothalamic dysfunction. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2021;9. [CrossRef]

- Tinano FR, Canton APM, Montenegro LR, de Castro Leal A, Faria AG, Seraphim CE, et al. Clinical and Genetic Characterization of Familial Central Precocious Puberty. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2023;108:1758–67. [CrossRef]

- Tajima T. Genetic causes of central precocious puberty. Clin Pediatr Endocrinol 2022;31. [CrossRef]

- Tenuta M, Carlomagno F, Cangiano B, Kanakis G, Pozza C, Sbardella E, et al. Somatotropic-Testicular Axis: A crosstalk between GH/IGF-I and gonadal hormones during development, transition, and adult age. Andrology 2021;9:168–84. [CrossRef]

- Xu YQ, Li GM, Li Y. Advanced bone age as an indicator facilitates the diagnosis of precocious puberty. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2018;94. [CrossRef]

- Cavallo F, Mohn A, Chiarelli F, Giannini C. Evaluation of Bone Age in Children: A Mini-Review. Front Pediatr 2021;9. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry S, Tadokoro-Cuccaro R, Hannema SE, Acerini CL, Hughes IA. Frequency of gonadal tumours in complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS): A retrospective case-series analysis. J Pediatr Urol 2017;13:498.e1-498.e6. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed ML, Ong KK, Dunger DB. Childhood obesity and the timing of puberty. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2009;20. [CrossRef]

- Silventoinen K, Jelenkovic A, Palviainen T, Dunkel L, Kaprio J. The Association Between Puberty Timing and Body Mass Index in a Longitudinal Setting: The Contribution of Genetic Factors. Behav Genet 2022;52. [CrossRef]

- Haddad NG, Eugster EA. Peripheral precocious puberty including congenital adrenal hyperplasia: causes, consequences, management and outcomes. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019;33. [CrossRef]

- Tarani L, Rasio D, Tarani F, Parlapiano G, Valentini D, Dylag KA, et al. Pediatrics for Disability: A Comprehensive Approach to Children with Syndromic Psychomotor Delay. Curr Pediatr Rev 2021;18:110–20. [CrossRef]

- Jrgensen A, Rajpert-De Meyts E. Regulation of meiotic entry and gonadal sex differentiation in the human: Normal and disrupted signaling. Biomol Concepts 2014;5. [CrossRef]

- Perluigi M, Di Domenico F, Buttterfield DA. Unraveling the complexity of neurodegeneration in brains of subjects with Down syndrome: Insights from proteomics. Proteomics - Clin Appl 2014;8:73–85. [CrossRef]

- Profeta G, Micangeli G, Tarani F, Paparella R, Ferraguti G, Spaziani M, et al. Sexual Developmental Disorders in Pediatrics. Clin Ter 2022;173:475–88. [CrossRef]

- Yu T, Yu Y, Li X, Xue P, Yu X, Chen Y, et al. Effects of childhood obesity and related genetic factors on precocious puberty: protocol for a multi-center prospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr 2022;22. [CrossRef]

- Lewis K, Lee PA. Endocrinology of male puberty. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2009;16. [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz O, Sari G, Mecidov I, Ozen S, Goksen D, Darcan S. The Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Analogue Therapy May Not Impact Final Height in Precocious Puberty of Girls With Onset of Puberty Aged 6 - 8 Years. J Clin Med Res 2019;11. [CrossRef]

- Macedo DB, Cukier P, Mendonca BB, Latronico AC, Brito VN. [Advances in the etiology, diagnosis and treatment of central precocious puberty]. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol 2014;58. [CrossRef]

- Liimatta J, Utriainen P, Voutilainen R, Jääskeläinen J. Girls with a history of premature adrenarche have advanced growth and pubertal development at the age of 12 years. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2017;8. [CrossRef]

- Novello L, Speiser PW. Premature adrenarche. Pediatr Ann 2018;47. [CrossRef]

- Wirth T. Fibrous dysplasia. Orthopade 2020;49:929–40. [CrossRef]

- Tanner Scale. Definitions, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Soto J, Pereira A, Busch AS, Almstrup K, Corvalan C, Iñiguez G, et al. Reproductive hormones during pubertal transition in girls with transient Thelarche. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2020;93:296–304. [CrossRef]

- Balzer BWR, Garden FL, Amatoury M, Luscombe GM, Paxton K, Hawke CI, et al. Self-rated Tanner stage and subjective measures of puberty are associated with longitudinal gonadal hormone changes. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2019;32. [CrossRef]

- Johannsen TH, Main KM, Ljubicic ML, Jensen TK, Andersen HR, Andersen MS, et al. Sex differences in reproductive hormones during mini-puberty in infants with normal and disordered sex development. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2018;103. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary S, Walia R, Bhansali A, Dayal D, Sachdeva N, Singh T, et al. FSH-stimulated Inhibin B (FSH-iB): A Novel Marker for the Accurate Prediction of Pubertal Outcome in Delayed Puberty. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2021;106. [CrossRef]

- Soriano-Guillén L, Argente J. Central precocious puberty: Epidemiology, etiology, diagnosis and treatment. An Pediatr 2011;74. [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson C. Testosterone measurements in early infancy. Arch Dis Child - Fetal Neonatal Ed 2004;89:F558–9. [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi MF. Physiology of puberty in boys and girls and pathological disorders affecting its onset. J Adolesc 2019;71. [CrossRef]

- Muerköster AP, Frederiksen H, Juul A, Andersson AM, Jensen RC, Glintborg D, et al. Maternal phthalate exposure associated with decreased testosterone/LH ratio in male offspring during mini-puberty. Odense Child Cohort. Environ Int 2020;144. [CrossRef]

- DiVall SA, Radovick S. Endocrinology of female puberty. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2009;16. [CrossRef]

- Willemsen RH, Elleri D, Williams RM, Ong KK, Dunger DB. Pros and cons of GnRHa treatment for early puberty in girls. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2014;10. [CrossRef]

- Cheuiche AV, da Silveira LG, de Paula LCP, Lucena IRS, Silveiro SP. Diagnosis and management of precocious sexual maturation: an updated review. Eur J Pediatr 2021;180. [CrossRef]

- Razzaghy-Azar M, Ghasemi F, Hallaji F, Ghasemi A, Ghasemi M. Sonographic measurement of uterus and ovaries in premenarcheal healthy girls between 6 and 13 years old: Correlation with age and pubertal status. J Clin Ultrasound 2011;39:64–73. [CrossRef]

- Haber HP, Wollmann HA, Ranke MB. Pelvic ultrasonography: Early differentiation between isolated premature thelarche and central precocious puberty. Eur J Pediatr 1995;154:182–6. [CrossRef]

- Badouraki M, Christoforidis A, Economou I, Dimitriadis AS, Katzos G. Evaluation of pelvic ultrasonography in the diagnosis and differentiation of various forms of sexual precocity in girls. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2008;32:819–27. [CrossRef]

- Yu J, Shin HY, Lee SH, Kim YS, Kim JH. Usefulness of pelvic ultrasonography for the diagnosis of central precocious puberty in girls. Korean J Pediatr 2015;58:294–300. [CrossRef]

- Messina MP, Piccioni MG, Petrella C, Vitali M, Greco A, Ralli M, et al. Advanced Midwifery Practice: Intrapartum Ultrasonography To Assess Fetal Head Station and Comparison With Vaginal Digital Examination. Minerva Obstet Gynecol 2021;73:253–60. [CrossRef]

- Spaziani M, Lecis C, Tarantino C, Sbardella E, Pozza C, Gianfrilli D. The role of scrotal ultrasonography from infancy to puberty. Andrology 2021;9:1306–21. [CrossRef]

- Oehme NHB, Roelants M, Bruserud IS, Eide GE, Bjerknes R, Rosendahl K, et al. Ultrasound-based measurements of testicular volume in 6- to 16-year-old boys — intra- and interobserver agreement and comparison with Prader orchidometry. Pediatr Radiol 2018;48:1771–8. [CrossRef]

- Pozza C, Kanakis G, Carlomagno F, Lemma A, Pofi R, Tenuta M, et al. Testicular ultrasound score: A new proposal for a scoring system to predict testicular function. Andrology 2020;8:1051–63. [CrossRef]

- Chadha NK, Forte V. Pediatric head and neck malignancies. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2009;17:471–6. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd C, McHugh K. The role of radiology in head and neck tumours in children. Cancer Imaging 2010;10:49–61. [CrossRef]

- Micangeli G, Menghi M, Profeta G, Tarani F, Mariani A, Petrella C, et al. The Impact of Oxidative Stress on Pediatrics Syndromes. Antioxidants 2022;11:1983. [CrossRef]

- Bulcao Macedo D, Nahime Brito V, Latronico AC laudi. New causes of central precocious puberty: the role of genetic factors. Neuroendocrinology 2014;100. [CrossRef]

- Dorn LD. Psychological and social problems in children with premature adrenarche and precocious puberty. Curr Clin Neurol 2010. [CrossRef]

- Klein KO, Lee PA. Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRHa) Therapy for Central Precocious Puberty (CPP): Review of Nuances in Assessment of Height, Hormonal Suppression, Psychosocial Issues, and Weight Gain, with Patient Examples. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev 2018;15. [CrossRef]

- Censani M, Feuer A, Orton S, Askin G, Vogiatzi M. Changes in body mass index in children on gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist therapy with precocious puberty, early puberty or short stature. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2019. [CrossRef]

- Song W, Zhao F, Liang S, Li G, Xue J. Is a combination of a GnRH agonist and recombinant growth hormone an effective treatment to increase the final adult height of girls with precocious or early puberty? Int J Endocrinol 2018;2018. [CrossRef]

- Cantas-Orsdemir S, Eugster EA. Update on central precocious puberty: from etiologies to outcomes. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab 2019;14. [CrossRef]

- Partsch CJ, Sippell WG. Treatment of central precocious puberty. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;16. [CrossRef]

- Głąb E, Wikiera B, Bieniasz J, Barg E. The influence of GnRH analog therapy on growth in central precocious puberty. Adv Clin Exp Med 2016;25. [CrossRef]

- Gła̧b E, Barg E, Wikiera B, Grabowski M, Noczyńska A. Influence of GnRH analog therapy on body mass in central precocious puberty. Pediatr Endocrinol Diabetes Metab 2009;15.

- Muratoğlu Şahin N, Dikmen AU, Çetinkaya S, Aycan Z. Subnormal growth velocity and related factors during GnRH analog therapy for idiopathic central precocious puberty. JCRPE J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol 2018;10. [CrossRef]

- Waal HAD-V De, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Delemarre-Van De Waal HA, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Clinical management of gender identity disorder in adolescents: A protocol on psychological and paediatric endocrinology aspects. Eur. J. Endocrinol. Suppl., vol. 155, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Mouat F, Hofman PL, Jefferies C, Gunn AJ, Cutfield WS. Initial growth deceleration during GnRH analogue therapy for precocious puberty. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2009;70. [CrossRef]

- Pienkowski C, Tauber M. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist treatment in sexual precocity. Endocr Dev 2016;29. [CrossRef]

- Fiore M, Tarani L, Radicioni A, Spaziani M, Ferraguti G, Putotto C, et al. Serum prokineticin-2 in prepubertal and adult Klinefelter individuals. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2021;100:151–7. [CrossRef]

- Ferraguti G, Fanfarillo F, Tarani L, Blaconà G, Tarani F, Barbato C, et al. NGF and the Male Reproductive System: Potential Clinical Applications in Infertility. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23:13127. [CrossRef]

- Ferraguti G, Terracina S, Micangeli G, Lucarelli M, Tarani L, Ceccanti M, et al. NGF and BDNF in pediatrics syndromes. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2023;145:105015. [CrossRef]

- Roberts SA, Kaiser UB. Genetics in endocrinology genetic etiologies of central precocious puberty and the role of imprinted genes. Eur J Endocrinol 2020;183. [CrossRef]

- Paparella R, Menghi M, Micangeli G, Leonardi L, Profeta G, Tarani F, et al. Autoimmune Polyendocrine Syndromes in the Pediatric Age. Children 2023;10. [CrossRef]

- Petrella C, Spaziani M, D’Orazi V, Tarani L, Terracina S, Tarani F, et al. Prokineticin 2/PROK2 and Male Infertility. Biomedicines 2022;10. [CrossRef]

| Tanner Stage | Breast (female) | Pubic hair (female, male) | Genitalia (male) |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Preadolescent | None | Preadolescent |

| II | Breast bud palpable under the areola | Sparse, long, straight | Enlargement of scrotum/testes |

| III | Breast tissue palpable outside areola; no areolar development | Darker, curling, increased amount | Penis grows in length; testes continue to enlarge |

| IV | Areola elevated above the contour of the breast, forming a “double scoop” appearance | Coarse, curly, adult type | Penis grows in length/breadth; scrotum darkens, testes continue to enlarge |

| V | Areolar mound recedes into single breast contour with areolar hyperpigmentation, papillae development, and nipple protrusion | Adult, extend to thighs | Adult shape/size |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).