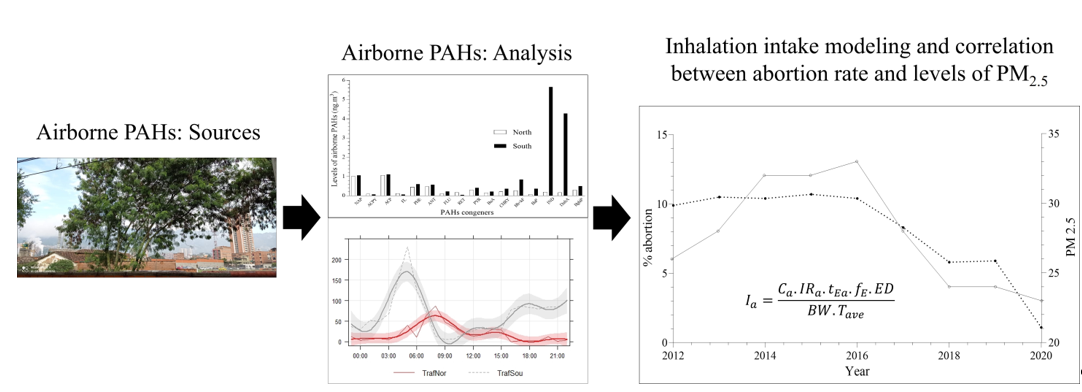

1. Introduction

Particulate Matter (PM) is produced by natural and human activities that pollutes air [

1,

2]. Depending on the source, PM may include a wide range of Polycyclic Aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) which cause health problems including endocrine disorders on vulnerable populations such as older adults, childhood, and pregnant women [

3]. The PAHs are produced principally by sources such as fuel fossil combustion, forest burning, and industrial emission. Those sources may suppose a risk of serious concern by long-term exposure. For instance, the PAHs concentrations in eastern China are mainly produced by industrial and traffic emissions which showed negligible cancer risks over humans, but children pose a higher risk than adults. Additionally, in this sense, it has found that living within a perimeter of 50 m of a road with high traffic was significantly associated with spontaneous abortion (SAB) [

4]. Thus, the screening of PAHs levels should focus on industrial and traffic emission for public health studies.

The effect of PAHs is higher in pregnant women because their body physiologically change to take more air [

5]. In this way, PAHs increase in their lungs since the air volume taken increases 10% more during pregnancy [

6]. As many airborne pollutants are in mother’s blood, PAHs may diffuse to the fetal environment by placenta-blood interchange [

7,

8]. Specifically, high concentrations of PAHs were found in mother blood by Drwal and coworkers [

9], and they even found benzo[a] pyrene (BaP), a carcinogenic congener, at concentrations of 0.75 ng.ml

-1. PAHs reduce their concentration four times crossing through the placenta, but this does not avoid their effect on the intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) [

10].

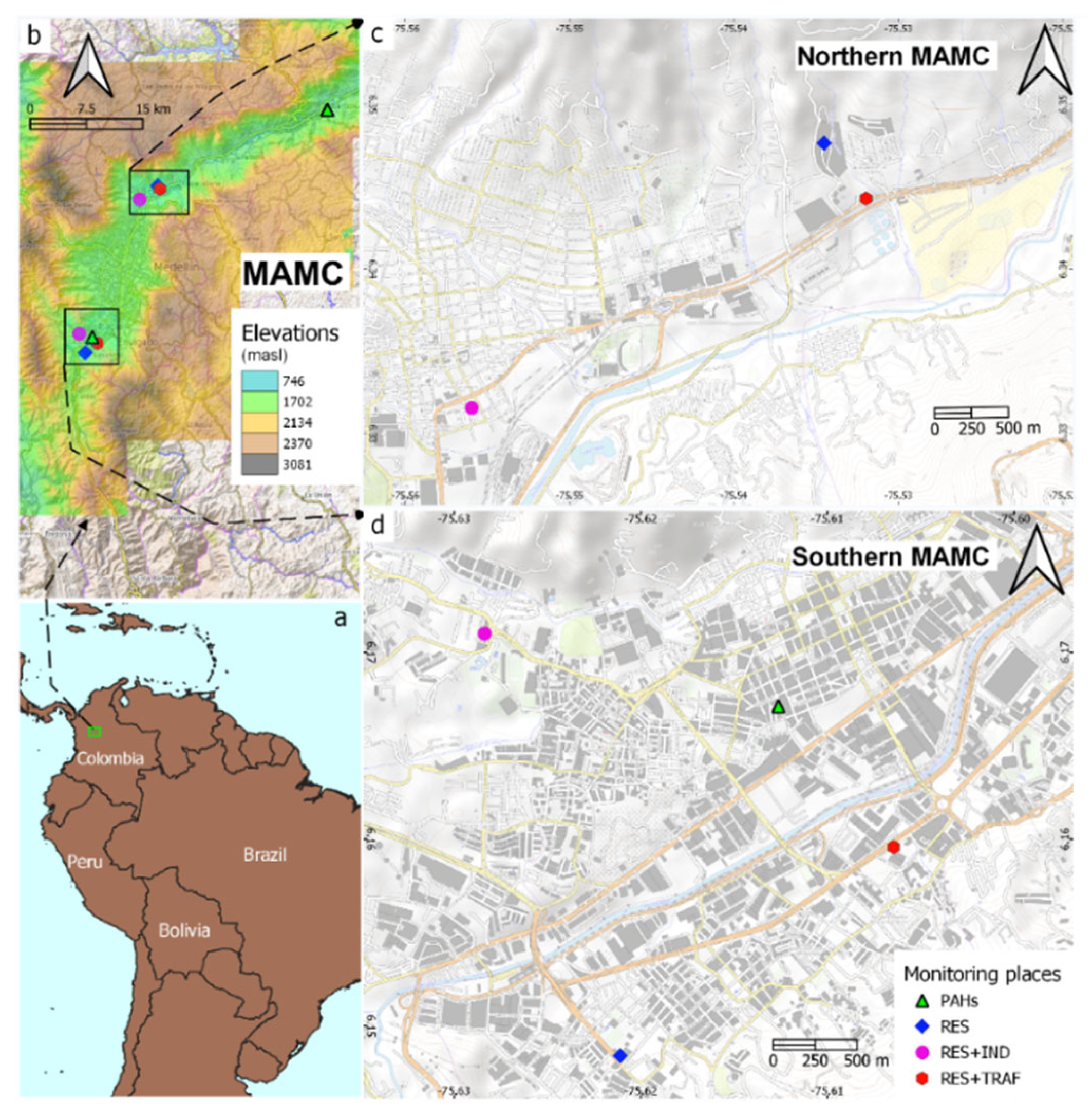

The Abortion rate in the MAMC has recently increased but the effect of air pollution on this tendency remains unknown. Although air quality has decreased in the last years ranking MAMC in the top-worst air quality in Latin America [

11], the main sources and receptors places (hazardous places for pregnancy exposure) of airborne PAHs are also unknown. The MAMC is located over the northwestern corner of tropical South America (See

Figure 1a). Specifically, it is placed over the mountains of the Colombian Andes inside of a very narrow and deep valley with elevations ranging between 1400 and 2400 m.a.s.l. This valley has a maximum width of 17 km and an average length of 45 km, its main river flows predominantly from South to North (See

Figure 1b). In general, the MAMC is influenced by a north-to-south direction of low-level atmospheric winds [

12]. This direction relies on the influence of the northeast trade-winds that dominates the climatology of this region [

13] and, for instance, it implies that it rains more over the southern than northern MAMC [

12]. In spite of better condition of employment rate, access to health system and per capita incomes are done in southern, this place show the higher abortion rate than northern in the MAMC which may be related to more industrial and vehicular emission and even the trade-winds direction increase the PAHs’ impact. However, those associations among PAHs’ impact, sources and trade winds have been not carried out in MAMC.

In this paper, we present a real-time tracking analysis in the MAMC for both individual airborne PAHs and total congeners by GC/MS and real-time monitoring as a preliminary association of abortion rate and air quality. Additionally, the distance between air pollution sources of pregnancy women may explain the risk for adverse perinatal outcomes. Therefore, we did our real-time monitoring of residential places locating the equipment at a minimum distance of 50 meters from the emission source including vehicles and industrial emission [

14], while the residential places influenced by traffic and industrial activity were located at a distance less than 50 meters from the emission source (

Figure 1c, 1d). Also, this monitoring was performed from September-October of 2021. This period represents a critical season for PM2.5 on the MAMC. See

Figure 1.

The airborne PAHs exposure was assessed using Inhalation Intake Modelling (IIM) to identify receptor places for risk assessment on pregnant women living in the MAMC. Also, applying a cross-sectional study in the last 15 years, the abortion rate series were correlated with the average levels of PM2.5. Finally, contrasting northern and southern of MAMC, PAHs levels were compared with abortion rate to identify the role of the predominant direction of a low-level atmospheric wind in the narrow valley where the MAMC is placed.

2. Materials and Methods

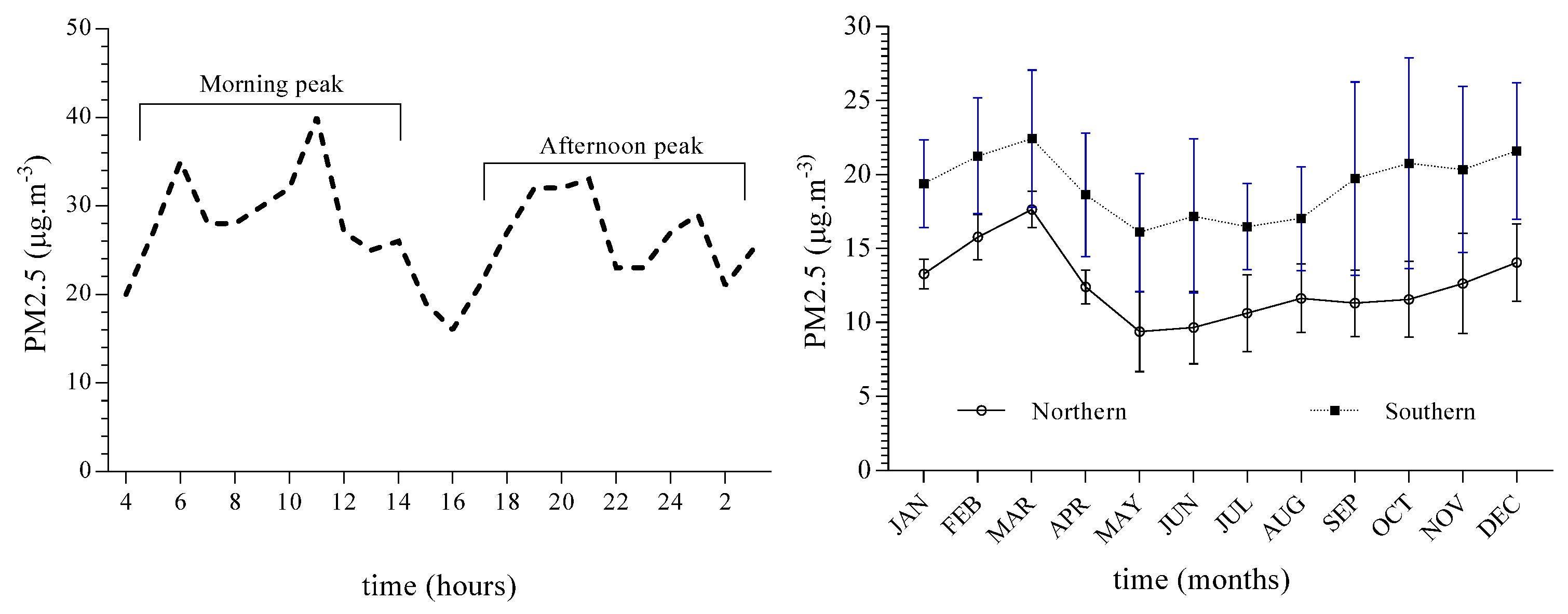

2.1. Study Area and Tendency for PM2.5

For real time monitoring of PAHs, three places were selected in both northern and southern MAMC. Rather, fixed air quality gauges were employed for PAHs analysis via GC/MS in both northern and southern areas. Refer to

Figure 2.

2.2. Chemical and Reagents

The stock solution of PAHs congeners (16 priority test), seven deuterated PAHs (quantification purposes), and stock solution of 16 individual PAHs were purchased in sigma Aldrich (Purity >99.5%). Similarly, hexane and methanol for extraction and preparing stock solution of PAHs were purchased in sigma Aldrich (Gas chromatography MS SupraSolv®). Finally, the capillary column (30 m, 0.25 mm, 0.15 μm) was supplied by Restek pure chromatography.

2.3. Airborne PAHs Analysis by GC/MS

Quartz filters for Particle-bound PAHs analysis were supplied by the MAMC which oversees air quality monitoring Network. Those filters were taken out from high flow samplers (Average flow of 1.13 m3.min-1 for 24 hours) which were deployed in southern and northern representatives’ places. The sampled filters were kept at -20°C. Therefore, filters were cut into small circular pieces (16 mm diameter), and those were extracted by Pressurized hot water extraction (PHWE) using a Thermo Scientific® Dionex® ASE® 350 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Sunnyvale, CA USA). The ratio 90:10 of water/methanol at 200°C, 2000 psi and only one cycle extraction was applied.

The aqueous extract was subjected to liquid-liquid micro-extraction with ultrapure hexane (Merck®, Darmstadt, Germany) and PAHs from organic phase were determined by a Thermo Scientific Trace® Ultra coupled to mass spectrometry detector (ISQ) in mode of Selected Ion Monitoring (SIM) under electronic impact (70eV). The PAHs congeners were separated on a Select PAHs Capillary Column (30 m, 0.25 mm (about 0.01 in), 0.15 μm) with an initial and final temperature of 70℃ and 320 ℃ respectively, using helium as the carrier gas (2 mL.min

-1). The quantification was done by seven deuterated internal standards (ISTD) [

15].

2.4. Monitoring of Total PAHs in Real-Time (Exposure Levels)

The PAHs analysis in real-time was carried out in a period ranging from September to November 2021 in the southern and northern of MAMC (See

Figure 1). This is a critical period coinciding with the second peak of the bimodal tendency for PM2.5 emissions in MAMC (See

Figure 1b). Regarding the geomorphological features and the predominant north-to-south wind’s direction in the MAMC, northern and southern places were chosen for PAHs’ monitoring (

Figure 2 c,d). The total level of airborne PAHs was monitored using Photoelectric sensor PAS 2000 (EcoChem Analytics, League City, TX, USA) with UV radiation detector. The range for quantification was between 0 to 4000 ng.m

-3 and a lower threshold of 10 ng.m

-3. The flow was 5 Liters per minute similar to minute ventilation during breathing in pregnancy and the device was deployed in each monitoring place for 24 hours. Data were collected in real-time by the software PAHDAS in txt file output and those were processed in Microsoft Excel format (2016 - v16.0) and the R Project for Statistical Computing. ®

2.5. Risk Assessment by Inhalation Intake for Pregnant Women

The risk by long-term inhalation exposure for pregnant women were assessed applying the inhalation intake (

Ia) model [

16]. See equation 1

where

Ca is the contaminant concentration in air (mg.m

-3),

IRa is the inhalation rate (m3.h-1),

tEa is the time which depends on duration of exposure (h.day

-1),

fE is the exposure frequency (day. year-1),

ED is the exposure duration (years),

BW is body weight (kg) and

Tave is the average period of exposure (day). The

Ia was estimated for exposure in southern and northern of the MAMC to assay the maximum pregnancy risk exposure in the city. The body weight was defined based on the average weight of woman in the MAMC (65 kg) + Recommended weight gain during pregnancy according to world health organization - WHO (12 kg).

2.6. Correlation between % of Abortion and the Average Levels of PM2.5 in the MAMC

The abortion rate was extracted from the harmonized databases of Dirección seccional de salud de Antioquia (DSSA-

https://dssa.gov.co/index.php/vigilancia-en-salud-publica ). This specific database works harmonized for both places (unique database). On the other hand, data for variation of PM2.5 were obtained from Sistema de Alertas Tempranas del Valle del Aburrá (SIATA-

https://siata.gov.co/siata_nuevo/ ). Both data were extracted between 2012 to 2020. The pregnant women between 25-34 years old were considered in location of south and north in the MAMC which is reported for their residential places regardless of where woman had the abortion.

Data were graphed for descriptive statistical analysis, tendencies, and differences of abortion rate between south and north by one-way ANOVA. Also, the set data were analyzed by Pearson correlation for tendencies study.

2.7. Diurnal Cycle of Winds and Air Temperature in MAMC

Wind and temperature at pressure levels (825-875 hPa) corresponding to the MAMC for September, October and November – 2021 which are related to the event for total PAHs and individual analysis by GC/MS. Data were taken from reanalysis ERA-5 downscaled at 12.5 Km.

2.8. Data Analysis

Data were plotted using the GraphPAD Prism 7.0 and R project. Differences between abortion rate of both south and north were estimated using a one-way ANOVA analysis and Pearson correlations (confidence interval >95%). Finally, PAHs data collected in real time were processed in Microsoft Excel format (2016 - v16.0) and the R Project.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Airborne PAHs (Levels Exposures)

All PAHs congeners were efficiently separated on the Select PAHs Capillary Column and those were identified by the target ion presented in

Table 1. Overall, the validation data indicate acceptable values for quantification purposes of particle-bound PAH by GC/MS analysis and PHWE. For instance, the PHWE showed a good recovery method (> 60%) using spiked deuterated surrogates while the limits of detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ), as well as the linearity, were significant for our quantification purpose (See

Table 1). Additionally, the homoscedasticity and even the

r2 (0.99) showed a good linearity. See

Table 1

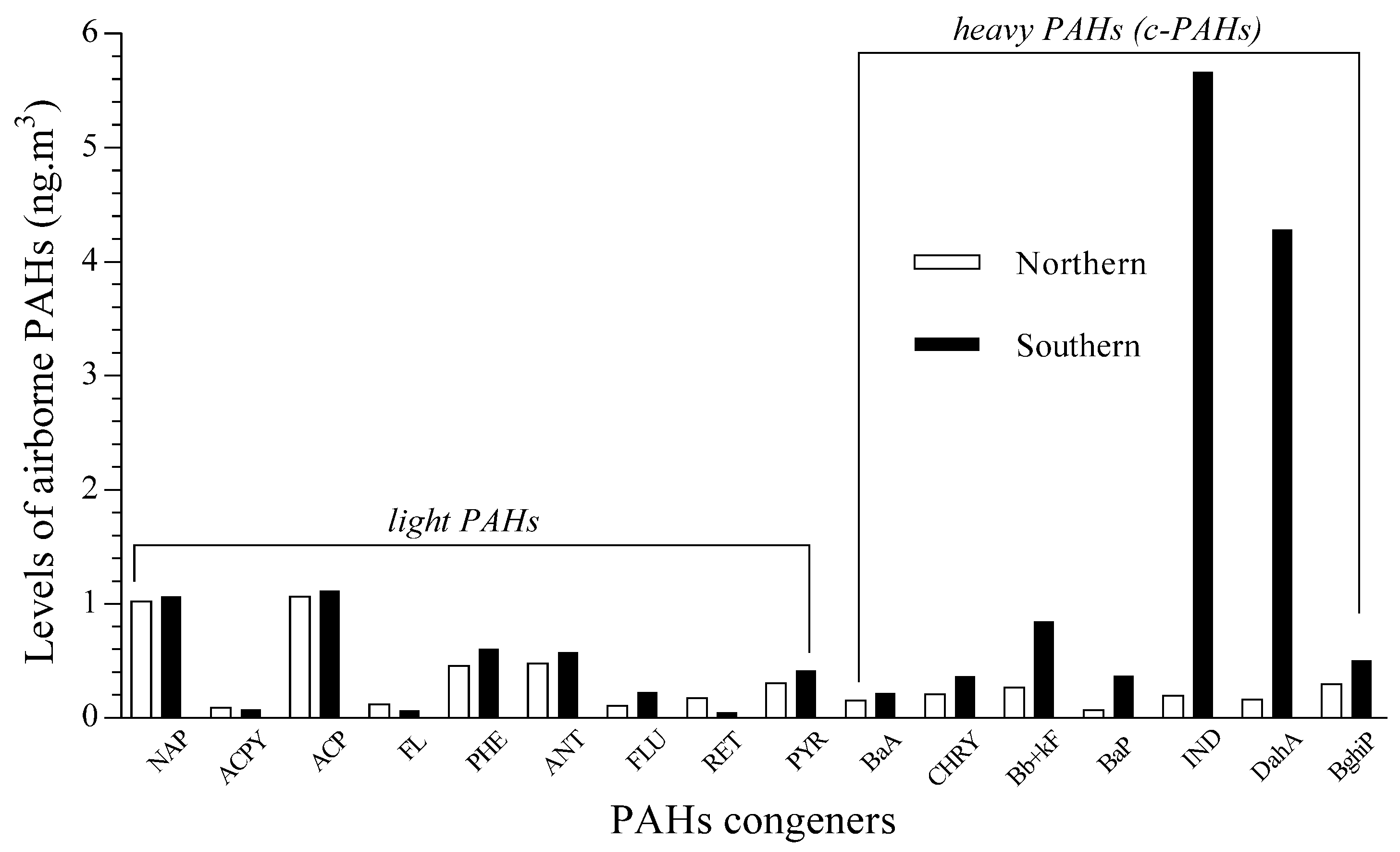

Low levels of PAHs were found in northern and southern, instead, the heavier congeners showed higher amounts (See

Figure 3).

The individual PAHs were found in PM from MAMC which showed differences between northern and southern for the total of PAHs congeners. Additionally, we found spatial differences in heavy PAHs levels assessed. The total of individual PAHs congeners showed a concentration of 5.3 ng.m

-3 in North-MAMC and 16.82 ng. m

-3 in South-MAMC. Therefore, the southern levels were 3.2 times higher than northern ones which indicates more PAHs levels exposure in southern (See

Figure 3). Similarly, the total of heavy PAHs in northern showed levels of 1.33 ng.m

-3 compared to southern which showed levels of 12.39 ng.m

-3. Those heavy PAHs are widely studied because of their carcinogenic potential effect (c-PAHs). The BaP is the main c-PAHs congener studied because of their major carcinogenic effects [

17]. This congener showed levels of 0.35 ng.m

-3 southern, while in the northern levels of 0.07 ng.m

-3 were found (See

Figure 3).

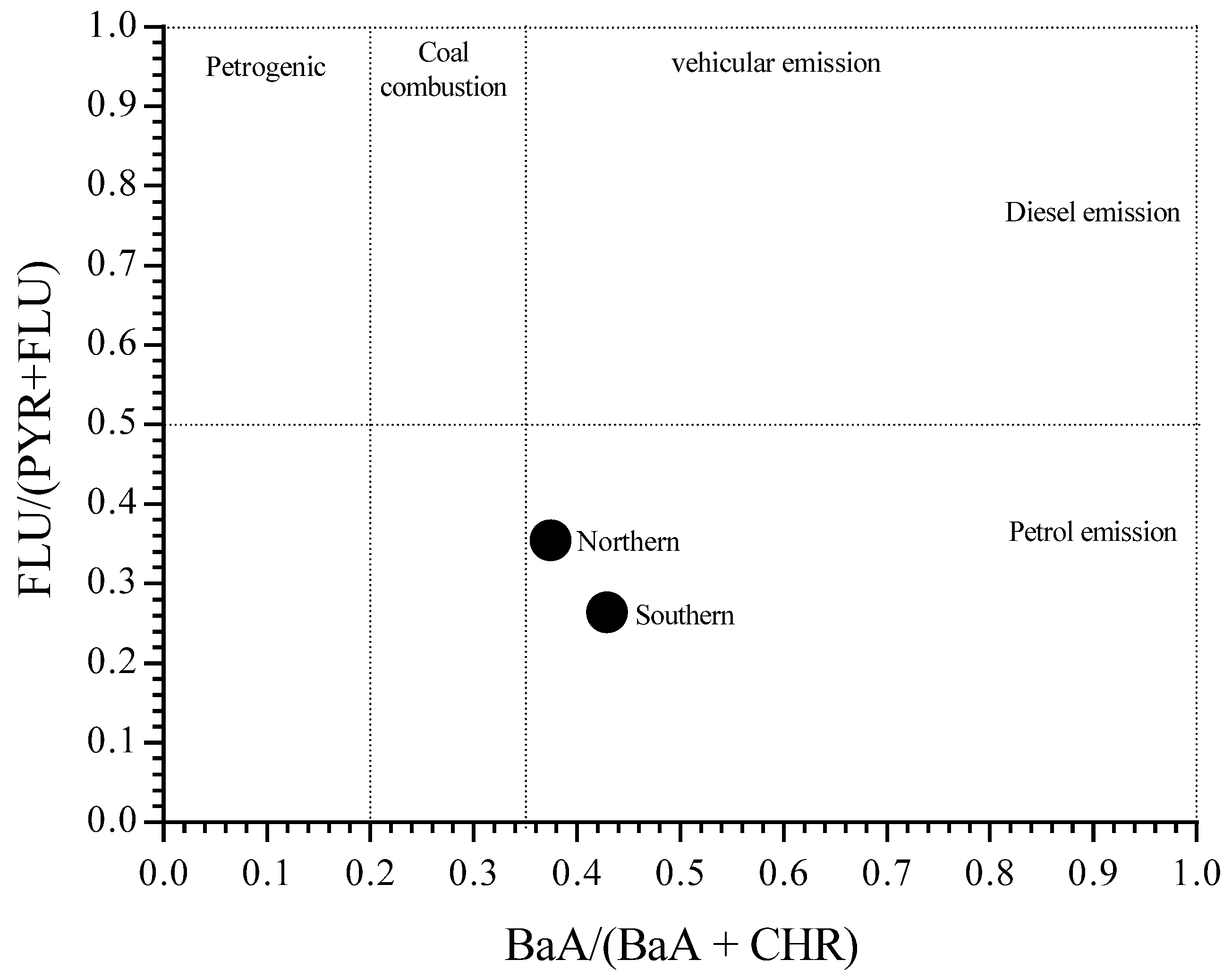

The Analysis of PAHs emission sources (Vehicular emission) showed that vehicular combustion is the main source of congeners’ contribution. See

Figure 4.

The sources of pollution emission in MAMC were identified based on previous research using diagnostic ratios between PAHs congeners [

18]. See

Figure 4. According to our results, vehicular emission (diesel and petrol) is a critical source for airborne PAHs and specifically the petrol emission is the main contribution. Therefore, the RES+TRAF may be consider as a higher risk.

Researchers report risk values for BaP y c-PAHs exposure. For instance, human exposure to approximately 1.6 ng.m

-3 of BaP or 10 ng.m

-3 of carcinogenic PAHs (c-PAHs) such as BaP, BaA, Bb+kF, BghiP, CHRY, DahA and IND increases DNA adducts and decreases repair efficiency [

19]. The c-PAHs (5-7 rings and molecular weight between 252 to 300 g.mol

-1) are associated with the breathable PM2.5 and therefore, those congeners such as BaP, CHRY, IND, DahA among others may be found in blood, placenta and maternal-fetal cord white blood cells in pregnant woman exposed to air pollution [

20,

21]. For instance, the BaP has been found at higher levels in placenta of preterm delivery group than full-term delivery group in case study research [

22]. Additionally, in a previous report, we found that the mixture of PAHs congeners such as ANT, FLU, PYR, BaP at low levels may affect gestational hormone production such as progesterone and β-hCG in a placental cell line which may explain the placental dysfunction and finally the adverse pregnancy outcomes [

23]. Therefore, the levels of PAHs found in the MAMC may represent a risk due to long term exposure. Also, a significate relationship between c-PAHs levels and decreasing concentration of redox biomarkers provides an indication of the oxidative stress pathways in preterm labor [

22].

In the southern MAMC, the levels of BaP were lower than the risk value to affect the DNA repair but the levels of c-PAHs overcome the thresholds which may affect DNA repair as a marker for genetic damage. See

Table 2 for reference values

Instead, the north MAMC does not overcome those risk values for BaP and c-PAHs exposure. According to the differences found, more studies should be carried out to assess the risk of incidences for genetic implications in southern by airborne PAHs.

3.2. PAHs Monitoring in Real-Time

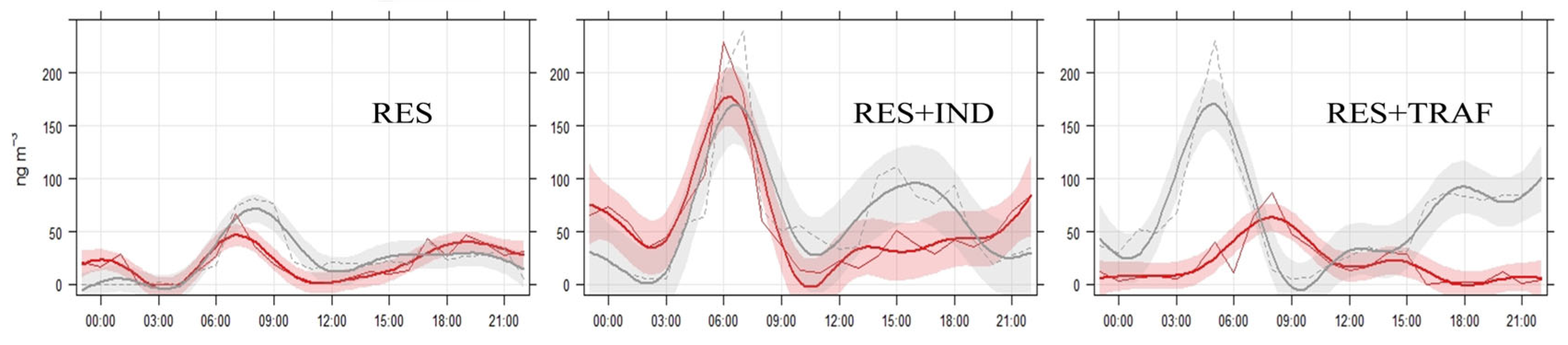

The level exposure of PAHs showed a diurnal variation in northern and southern MAMC (See

Figure 5). Overall, we found higher levels of PAHs in RES+IND and RES+TRAF than RES in both northern and southern places which revealed the contribution of those substances by anthropogenic activities.

According to

Figure 5, the RES+TRAF and RES+IND showed higher levels of airborne total PAHs than RES in a bimodal behavior (Morning and afternoon peaks). The diurnal PAHs analysis shows a similar tendency for a concentration of PM2.5 in MAMC (

Figure 2). Moreover, the analysis of airborne PAHs in real-time showed levels > 50 ng.m

-3 in rush hours for total PAHs in RES while, RES+TRAF, and RES+IND may reach values three times higher (>150 ng.m

-3). Similarly, the airborne total PAHs in southern are slightly higher than northern. The morning peak of PAHs levels approximately occurs between 06:00 to10:00 local standard time (LST) and the afternoon peak occurs between 16:00 to 20:00 LST. This afternoon peak is triggered by the rush hour coinciding with the average diurnal patterns of air pollution in the MAMC [

24]. Since MAMC is located on the tropical region, the diurnal temperature range has longer variability than the annual range, and consequently the diurnal patterns of PAHs could be more affected by these fluctuations [

25]. Specifically, the morning peak of PAHs is higher than the afternoon peak due to a complex interaction among surface temperature (night/early morning gradient), thermal inversion, and condensation which affect the dynamic of gases and particles in the boundary layer. Additionally, the air particles are condensed producing a stable layer which is re-suspended early morning in MAMC due to temperature [

26]. See

Figure 6 for diurnal wind and temperature cycle.

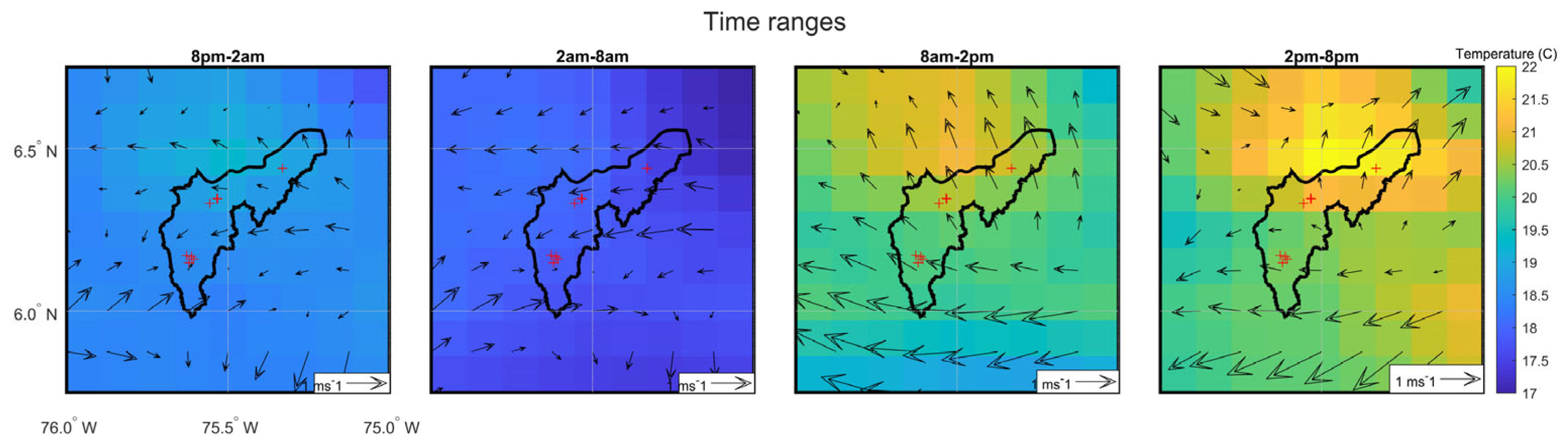

During the range 8 pm to 8 am when the temperature decreases during the diurnal cycle, the wind direction domain from northern to Southern (see

Figure 6). When the temperature increases at time ranging 8 am-2pm, the easterly and southeasterly winds domain the transport of aerosols. Finally, from 2 pm- 8 pm the temperature reaches its maximum values, and, the easterly winds domain the cycle but a southerly wind appears in northern MAMC.

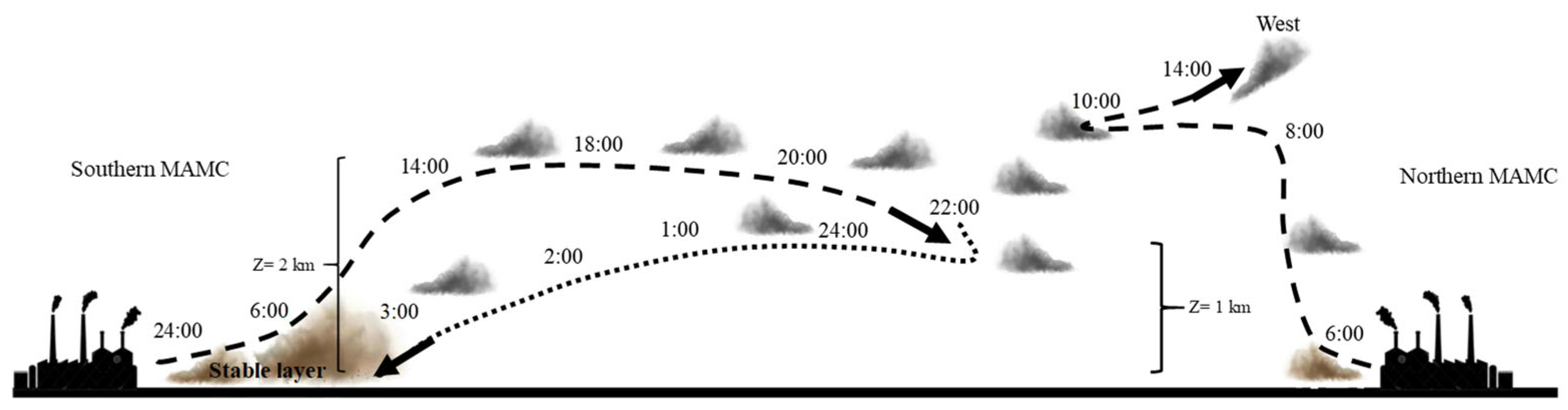

Due to minimum temperatures at early morning, a bigger stable layer is located in southern MAMC. Then after 8 am the temperature increases and consequently the aerosols are resuspended to higher elevations in southern MAMC. The resuspended aerosol may stay during morning just to the easterly winds start to blow. Thereby, if the elevation aerosols reach the top of mountains, the aerosols may be depurated. Instead, the aerosols are confine below the top of mountains, they are re-transported to north when the wind domain in this direction (2 pm – 8pm). Since after 8 pm the temperature decreases and the north-easterly wind domain, the aerosols are deposited again reaching its the higher levels as a stable layer in southern MAMC. Similarly, a small stable layer is formed in northern MAMC but the temperature gradients and wind direction move the aerosols to south and some amounts are depurated by winds because the northern temperatures are higher allowing the higher elevation of aerosols and its depuration to west.

Figure 7 shown the conceptual model for aerosol transport in MAMC. The information is consistent with diurnal levels of PM2.5 reported in Sistema de Alertas Tempranas del Valle del Aburrá (SIATA-

https://siata.gov.co/siata_nuevo/ ). For instance, higher levels are found in southern MAMC between 23:00 to 7:00 am compared to Northern MAMC when the stable layer is formed.

According to the wind analysis, although some industries and high quantity of vehicles per citizen are found in northern of MAMC, the trade winds show influences over the MAMC (Valley) from north to south which contributes to PM transport in this way [

27,

28].

According to our results, the only RES showed the lower exposure of PAHs for pregnant women were located in which are far away (50 meters) from vehicles and industries emissions. However, more studies should be carried out to estimate the safety perimeters.

3.3. Inhalation Intake Risk Assessment for Pregnancy Women

The inhalation intake risk model showed higher values in southern than northern MAMC and also the highest risk was found in RES+TRAF and RES+IND. The risk assessment for comparing the pregnancy exposure to PAHs between northern and southern MAMC is presented in

Table 2. The

Ia value was estimated applying equation 1.

In southern MAMC, the inhalation intake over RES+TRAF and RES+IND was three times higher than over RES (See

Table 2). Additionally, as it was presented before, the total concentration of airborne PAHs in southern was 3.2 times higher than northern. According to data reported about abortion in the MAMC the ratio for the south is twofold higher than north [

24]. This fact 2suggests a relationship between vehicular and industrial emissions and a higher exposure during pregnancy. In this sense, Rochelle and coworkers showed that living within a perimeter of 50 m of a road with high traffic was significantly associated with spontaneous abortion (SAB) [

14]. Additionally, Perera et al found that airborne PAHs may be associated with abortion mechanisms because some congeners bound to DNA (PAH–DNA adducts) in maternal-fetal cord white blood cells [

20]. Therefore, the association between abortion and airborne PAHs exposure should be considered in risk assessment for pregnant woman.

On another hand, low levels of RET congener in the MAMC indicate that wildfire is not the principal source for PAHs emission. For more detail see

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. Actually, the principal sources for airborne PAHs detected around RES are from fuel burning such as traffic and factories [

29]. In summary, the main source for airborne PAHs in MAMC is the vehicular emission specifically the petrol fuel (See

Figure 4). Additionally, as it was presented before, the heavier congeners such as Bb+kF, BeP, BaP, IND, DahA and BghiP (c-PAHs) showed the highest differences between northern and southern in MAMC. Those congeners are usually detected in PM 2.5 and PM10 due to more lipophilic properties and related to the IUGR at levels over 40 μg.m

-3 by exposure in the first gestational month [

30].

3.4. Implication of Air Pollution Exposure on Pregnancy in the MAMC

Air pollution increases pregnancy disorders such as the abortion rate which is even higher in most pollutant cities [

31]. For developed countries, the pregnancy outcomes and maternal care are relevant, then abortion is a worldwide concern. However, abortion etiology is a multifactorial issue where air pollution plays a key role [

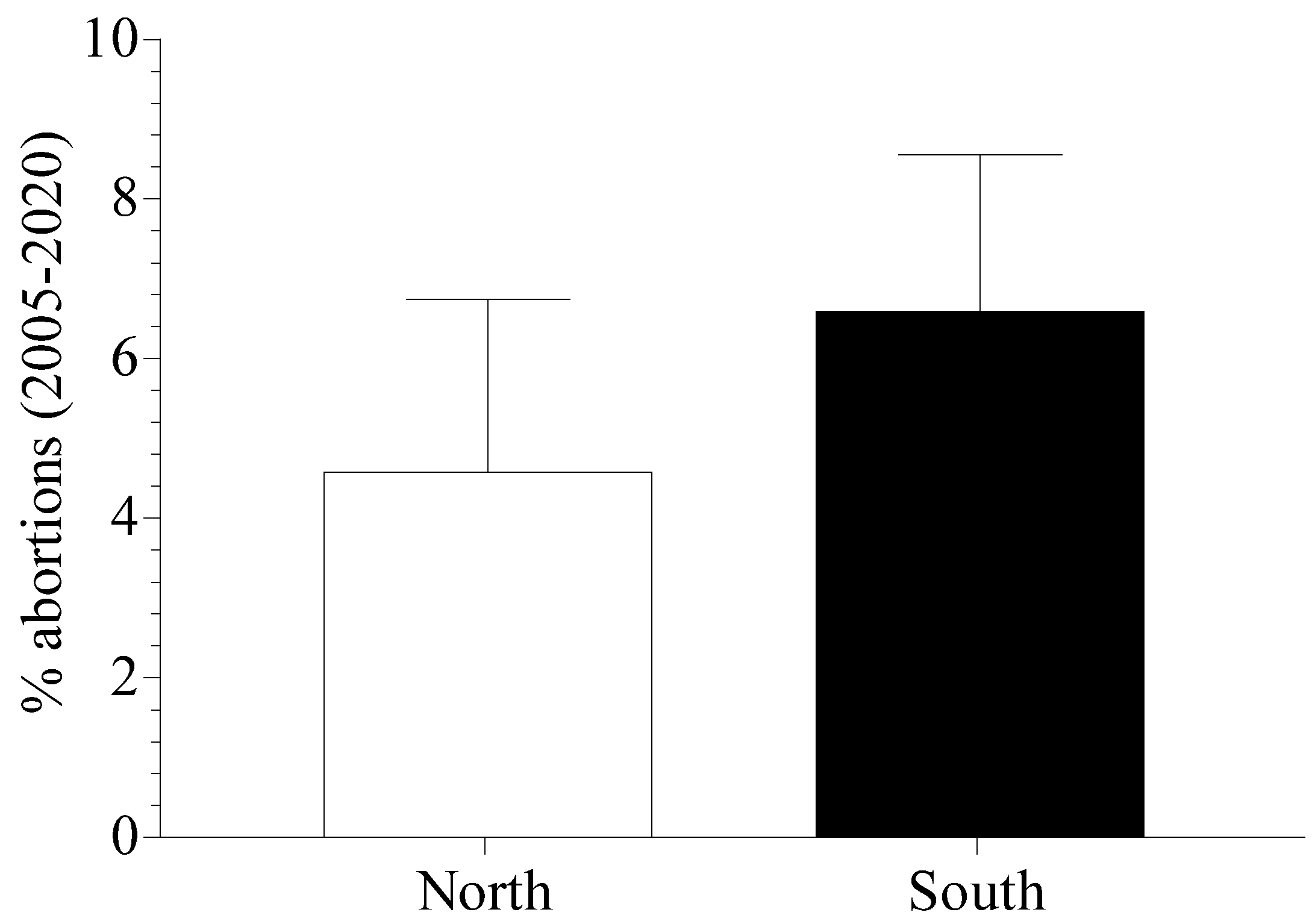

31]. In this research, the abortion rate in the MAMC was analyzed by applying a t-student test finding a significant difference of abortion between northern and southern MAMC (

p < 0.05). In summary, the southern abortion rate in the period 2005 – 2020 was 1.4 times higher than northern MAMC (See

Figure 8).

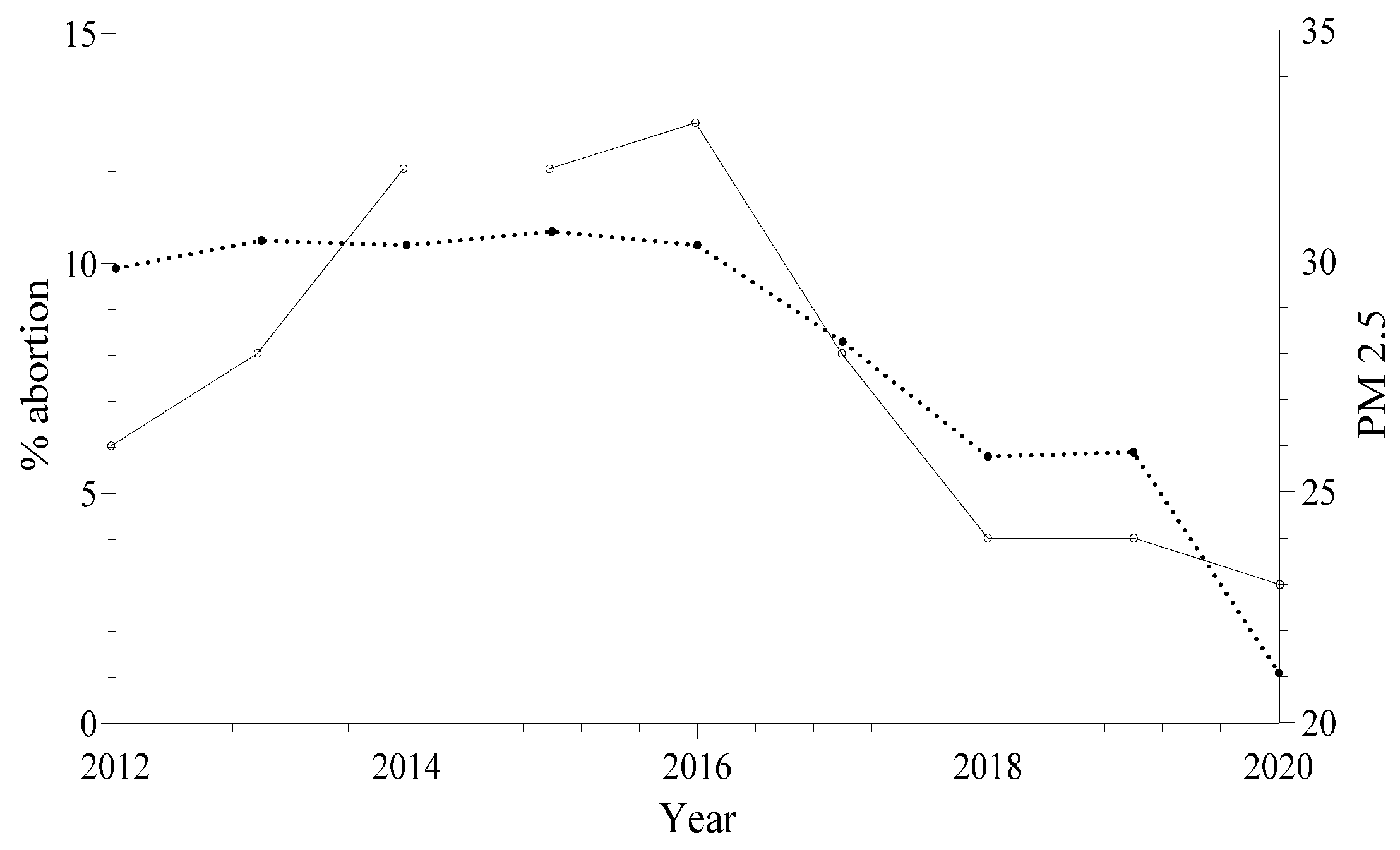

The annual series of abortion rates (2012-2020) in the MAMC showed a significant correlation with the annual average levels of PM2.5 (Pearson

r= 0.8031,

p-value < 0.01). (See

Figure 5). Although this significant correlation does not imply causality, our results suggest an important connection between both variables. For instance, 2016 was a critical year for air pollution in the MAMC and this coincided with the highest abortion rate. The average of PM2.5 value in 2016 was higher than 33 μg.m

-3 as the abortion rate was 10.3% (ages ranging between 25-34 years old). Briefly, 2016 was an inflection year for both variables: before 2016 the levels of PM2.5 were directly proportional to the abortion rate (uptrend) while after 2016 both series decreased (downtrend). (See

Figure 8).

At global scale, the PM2.5 and even airborne PAHs have been linked with the increasing of abortion rate [

32]. Similarly, at the local scale (MAMC) we have found a preliminary association between PM2.5 (Associated to PAHs) and abortion rate. For this reason, public health strategies in the MAMC should focus on the suitable management of PM2.5 emissions and also on more basic protection measures such as air masks. The air mask has been proved as an effective tool to reduce reproductive disorders during air pollution events [

32]. However, the abortion rate has been not deeply studied in the MAMC and also future research should include the role of comorbidities as another study variable.

Overall, the MAMC has shown an abortion rate around 10% (2005-2016) in healthy women (Not comorbidities) in age ranges between 25-34 years old. Spatially, abortion rate showed clear differences between southern and northern MAMC; likewise, southern total PAHs were 3.2 times higher than northern MAMC. The higher level of PAHs in the southern are related to industrial activities, and traffic vehicles. Also, the trade winds transport the PM2.5 from northern to southern and thus the PAHs from industries/traffic may follow the predominant north-south wind pathway. Probably, the southern MAMC represents a higher risk for short-term exposure during pregnancy. Overall, the conceptual model presented in

Figure 7 may explain why heavy congeners for PAHs such as BaP, DahA and IND were predominantly found in southern MAMC.

The Ia in southern MAMC showed to be higher than northern. In our cross-sectional study the abortion rate in the south was 1.5 times higher than north and therefore, our results may find an association between airborne PAHs and abortion in the MAMC. Additionally, we found more amounts of total PAHs in residential places with traffic and industrial influences meaning that sources such as vehicles and industries around the pregnancy population may increase the risk for adverse perinatal outcomes. However, this is a preliminary study, and more studies should be carried out in the future.

The human mobility was identified as a potential bias in this research. Thereby, pregnancy women exposure to PAHs may result from the mobility by several places. However, the higher exposure may occur in their residential places where they spend most of their time. Those limitations may create uncertainty which should be cope in future studies. For instance, remote sensors and geo-spatial big data should be applied to identified mobility [

32]. Here, we applied a PAHs analysis in real time to identified levels exposures in residential places influenced by traffic and industrial emission. Therefore, we found lower or higher risk for people living under those conditions.

Finally, older people, pregnant women and childhood are considered as vulnerable populations during air pollution emergencies in the MAMC. Particularly, safety perimeters in cities should be considered to avoid adverse pregnancy outcomes [

33]. This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

5. Conclusions

Southern PAHs levels are higher than northern levels and at the same time significantly correlated with PM2.5 with abortion rates in the MAMC. As the traffic and industrial are principal sources of PAHs in the MAMC, we suggest designing safety perimeters for pregnancy development ensuring located them far away from emission sources. We found that petrol emission is the main source for airborne PAHs, thus, fuel transition should be considered because the narrow morphology in this Valley and the thermal inversion decreases the atmospheric depuration in this place. Although, the industrial emission should be controlled by environmental authorities, similarly the location of industries in north should be evaluated, because the transport by trade winds is dominant from north to south which affect the air quality by air transport.

The highest risk was found in the southern MAMC implying more intensive protection measures there. This higher risk may be related to industrial and traffic sources influenced by air pollution dynamics in MAMC.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.J.M-P; methodology, S.V.A-B, V.C-G and J.J.G-L; validation, C.D.R-C, G.B.V-G and G.G. P-C; formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation and supervision, J.F.N-V and J.M.B-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The materials and methods were supported by grants from Corporación Universitaria Remington (Project code: 4000000098 and project code 4000000316)

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Acknowledgments

The authors thank to the research project Ensayo de disrupción endocrina de micro-contaminantes acumulados en prótesis mamarias de silicona por medio de passive dosing y expresión de la hormona β-hCG en la línea celular BeWo (Project code: 4000000098). Furthermore, the authors thank to the research Project Escalamiento en procesos hidrológicos en los Andes de Colombia (Project code: 4000000316). Finally, the authors thank the GAIA group for analyzing samples and for technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest with regard to the published results.

References

- Bo, M.; Salizzoni, P.; Clerico, M.; Buccolieri, R. Assessment of Indoor-Outdoor Particulate Matter Air Pollution: A Review. Atmosphere 2017, 8, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phairuang, W.; Suwattiga, P.; Chetiyanukornkul, T.; Hongtieab, S.; Limpaseni, W.; Ikemori, F.; Hata, M.; Furuuchi, M. The influence of the open burning of agricultural biomass and forest fires in Thailand on the carbonaceous components in size-fractionated particles. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 247, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-H.; Jahan, S.A.; Kabir, E.; Brown, R.J.C. A review of airborne polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and their human health effects. Environ. Int. 2013, 60, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green RS, Malig B, Windham GC, Fenster L, Ostro B, Swan S. Residential Exposure to Traffic and Spontaneous Abortion. Environ Health Perspect. 2009, 117, 1939–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marca L La, Gava G. Air Pollution Effects in Pregnancy. In: Clinical Handbook of Air Pollution-Related Diseases. Springer; 2018. p. 479–94.

- Korten, I.; Ramsey, K.; Latzin, P. Air pollution during pregnancy and lung development in the child. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2017, 21, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, X.; Wang, Q.; Peng, J.; Wu, M.; Pan, B.; Xing, B. Transfer of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from mother to fetus in relation to pregnancy complications. Sci. Total. Environ. 2018, 636, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, B.; Tao, S.; Liu, W.; Wang, X.; Cao, J.; Li, B.; Lu, X.; Wong, M.H. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Residues in Human Milk, Placenta, and Umbilical Cord Blood in Beijing, China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 10235–10242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drwal, E.; Rak, A.; Gregoraszczuk, E.L. Review: Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)—Action on placental function and health risks in future life of newborns. Toxicology 2019, 411, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 10. Detmar J, Rennie MY, Whiteley KJ, Qu D, Taniuchi Y, Shang X, et al. Fetal growth restriction triggered by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons is associated with altered placental vasculature and AhR-dependent changes in cell death. Am J Physiol - Endocrinol Metab 2008, 295.

- Rodríguez-Villamizar, L.A.; Rojas-Roa, N.Y.; Fernández-Niño, J.A. Short-term joint effects of ambient air pollutants on emergency department visits for respiratory and circulatory diseases in Colombia, 2011–2014. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 248, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedoya-Soto JM, Aristizábal E, Carmona AM, Poveda G. Seasonal shift of the diurnal cycle of rainfall over medellin’s valley, central andes of Colombia (1998–2005). Front Earth Sci. 2019, 7.

- Poveda, G. La hidroclimatología de colombia: una síntesis desde la escala inter-decadal hasta la escala diurna. 2004, 28, 201–221. [CrossRef]

- Green RS, Malig B, Windham GC, Fenster L, Ostro B, Swan S. Residential Exposure to Traffic and Spontaneous Abortion. Environ Health Perspect. 2009, 117, 1939–44.

- Contreras, I.R.; Contreras, C.R.; Perez, F.M.; Grana, E.C. Optimization of an environmentally sustainable analytical methodology for the determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in PM10 particulate matter. Conf Proc - Congr Colomb y Conf Int Calid Aire y Salud Publica, CASAP 2019. 2019;2019-Janua. [CrossRef]

- Aral, M.M. Environmental Modeling and Health Risk Analysis (Acts/Risk). 2010. [CrossRef]

- Saleh SAK, Adly HM, Aljahdali IA, Khafagy AA. Correlation of Occupational Exposure to Carcinogenic Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (cPAHs) and Blood Levels of p53 and p21 Protiens. Biomolecules 2022, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Tobiszewski, M.; Namieśnik, J. PAH diagnostic ratios for the identification of pollution emission sources. Environ. Pollut. 2012, 162, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binkova, B.; Chvatalova, I.; Lnenickova, Z.; Milcova, A.; Tulupova, E.; Farmer, P.B.; Sram, R.J. PAH–DNA adducts in environmentally exposed population in relation to metabolic and DNA repair gene polymorphisms. Mutat. Res. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2007, 620, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, F.P.; Jedrychowski, W.; Rauh, V.; Whyatt, R.M.; D, L.; J, R.; J, L.; M, H.; Y, H.; H, P.; et al. Molecular epidemiologic research on the effects of environmental pollutants on the fetus. Environ. Heal. Perspect. 1999, 107 (SUPPL. 3), 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumova, Y.Y.; Eisenreich, S.J.; Turpin, B.J.; Weisel, C.P.; Morandi, M.T.; Colome, S.D.; Totten, L.A.; Stock, T.H.; Winer, A.M.; Alimokhtari, S.; et al. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Indoor and Outdoor Air of Three Cities in the U.S. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 36, 2552–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.; Singh, L.; Anand, M.; Taneja, A. Association Between Placental Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHS), Oxidative Stress, and Preterm Delivery: A Case–Control Study. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2018, 74, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valderrama, J.F.N.; Gil, V.C.; B, V.A.; Tavera, E.A.; Noreña, E.; Porras, J.; Quintana-Castillo, J.C.; L, J.J.G.; P, F.J.M.; Ramos-Contreras, C.; et al. Effects of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons on gestational hormone production in a placental cell line: Application of passive dosing to in vitro tests. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 245, 114090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedoya J, Martínez E. Calidad del aire en el valle de aburrá Antioquia-Colombia. DYNA. 2009, 76, 7–15.

- Zhu, Y. , Yang, L., Meng, C., Yuan, Q., Yan, C., Dong, C., Sui, X., Yao, L., Yang, F., Lu, Y., & Wang, W. In-door/outdoor relationships and diurnal/nocturnal variations in water-soluble ion and PAH concentrations in the atmospheric PM2.5 of a business office area in Jinan, a heavily polluted city in China. Atmospheric Research 2015, 153, 276–285. [Google Scholar]

- Rendón, A.M.; Salazar, J.F.; Palacio, C.A.; Wirth, V.; Brötz, B. Effects of Urbanization on the Temperature Inversion Breakup in a Mountain Valley with Implications for Air Quality. J. Appl. Meteorol. Clim. 2014, 53, 840–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Mejía, L.; Hoyos, C.D. Characterization of the atmospheric boundary layer in a narrow tropical valley using remote-sensing and radiosonde observations and the WRF model: the Aburrá Valley case-study. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2019, 145, 2641–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa M, Zuluaga C, Palacio C, Pérez J, Jiménez J. Surface wind coupling from free atmosphere winds to local winds in a tropical region within complex terrain. Case of study: Aburrá Valley Antioquia, Colombia. Dyna. 2009, 76, 17–27.

- Lung, S.-C.C.; Liu, C.-H. Fast analysis of 29 polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and nitro-PAHs with ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-atmospheric pressure photoionization-tandem mass spectrometry. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šrám, R.J.; Binková, B.; Rössner, P.; Rubeš, J.; Topinka, J.; Dejmek, J. Adverse reproductive outcomes from exposure to environmental mutagens. Mutat. Res. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 1999, 428, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, B.T.; Chang, E.J.; Bendikson, K.A. Advanced paternal age and the risk of spontaneous abortion: an analysis of the combined 2011–2013 and 2013–2015 National Survey of Family Growth. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 221, 476–e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Huang, B.; He, Q.; Chen, B.; Wei, J.; Mahmood, R. Dynamic assessment of PM2.5 exposure and health risk using remote sensing and geo-spatial big data. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 253, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Zheng, H.; Liu, J.; Cai, J.; Wang, G.; Li, Y.; Shen, H.; Yang, J.; Wang, X.; Wu, J.; et al. The correlation between chronic exposure to particulate matter and spontaneous abortion: A meta-analysis. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).