1. Introduction

The USDA defines food security as “access by all people at all times to enough food for an active, healthy life [

1].” This definition is further expanded in the literature to emphasize the need for access to sustainable and culturally relevant food options for all individuals within a community [

2]. In the United States, there are currently over 34 million people experiencing food insecurity, nine million of whom are children [

3]. The negative public health effects of food insecurity are apparent, as studies show food insecurity is linked to the prevalence of chronic disease, particularly type 2 diabetes, and hypertension, in communities across the U.S. and around the world [

4,

5]. In Pittsburgh, one in five residents is considered to be food insecure, and in Allegheny County there are over 161,000 food insecure people [

6,

7]. These food insecurity rates for southwest Pennsylvania were exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic [

8]. In many cities, job- insecure individuals experienced food insecurity directly related to the pandemic [

9]. In light of the evolving challenges of maintaining resiliency in regional food systems, this research explores the relationship between public transportation access and rates of food insecurity. If a grocery store is present in a community, but the nearest public transportation stop is a long walk away, members of the community may elect inadequate alternatives to meet their food needs. This may render communities with long walks to food outlets for food insecure, perpetuating barriers to access established by the built environment in urban, mid-urban, and suburban areas. In addition, this can pose a unique challenge for some segments of the population which are known to be disproportionately impacted by lack of access to healthy and affordable. Thus, we explore the unique impact the lack of access to transportation has on women’s access to healthy food an link to their overall well-being.

1.1. Food Insecurity and Women’s Well-Being

Food insecurity also has disproportionate health and well-being ramifications for women, which is particularly relevant for female-headed households. One study found that female-headed households were 75% more likely to experience food insecurity when compared to male-headed households [

10]. Studies posit that the increased likelihood of food insecurity to female-headed households is partially the byproduct of a food system constructed on oppressive gender roles for women [

11]. One study found there to be a gendered obligation for women to ensure the health of the children, even at the sacrifice of their own health and nutritional needs [

12]. Holistically, food insecurity has a detrimental impact on a woman’s diet, effecting all components of the diet beyond simply fruit and vegetable intake [

13]. Specifically, research finds that food insecure women have a higher intake of carbohydrates, opting to minimize costs through selection of pasta and bread [

13]. Between the gender constraints women face, as well as income restraints, single mothers especially are at immense risk for diet-related chronic illness like obesity [

14]. In addition to the susceptibility to chronic illness due to these social pressures, food insecure women also have worse mental health than food secure women [

15]. While this may seem intuitive, it’s key to point out that the detriment to mental health of food insecurity has an exponential impact when coupled with pregnancy [

15]. These physical and mental health effects were exacerbated for women by the covid-19 pandemic [

16]. Also, sexual minority women were found to be at greater risk for experiencing food insecurity disparities, which is anticipated to be driven not only by the disproportionate burden of food insecurity on women, but also homophobic and heterosexist conditions in society that deplete economic resources, specifically including employment and wages [

17]. This leads to an inequitable distribution of health risks, including chronic disease stemming from food insecurity [

17]. Disparities in household food insecurity in the U.S. among female and male headed households are evident. In 2021, 24.3% of female-headed households in the U.S. experienced food insecurity, while only 16.2% of male-headed households experience the same [

18]. A similar disparity, though not as dramatic, was determined for women living alone, who experience greater food insecurity than men [

18].

1.2. Defining & Measuring Food Insecurity

A lack of access to food has been traditionally defined by the presence of a grocery store or supermarket, and roughly one third of all zip codes in the U.S. do not have either food outlet [

19]. However, the term “food desert” has evolved. Karen Washington [

20], food justice activist and founder of Rise & Root Farm, coined the term “food apartheid” so emphasize the systemic racism and economic inequality that influences food insecurity in marginalized communities [

21]. Economic inequality has often been associated with food insecurity, as studies have shown affluent communities often have greater access to nutritious food [

22,

23]. Increased access to healthy food is generally associated with lower rates of type 2 diabetes, and one study found that black Americans have generally less physical proximity to food [

24]. Another study found that as neighborhood poverty increased, presence of grocery stores and supermarkets increased, and predominately black census tracts had the lowest presence of supermarkets [

25]. In the U.S. the odds of having type 2 diabetes are higher for black Americans than any other race, and these odds are further increased for lower income individuals [

26]. Food apartheids are inherently complex, as a number of root causes can contribute to the prevalence of food insecurity in a community. The concept of “food mirages” asserts that even though there may be a grocery store present in a community, the prices of healthy food within the grocery store are not affordable to individuals in the low-income bracket [

27]. The research begins to further expand the perception of food apartheids beyond solely the presence of a grocery store in a community. A food mirage ultimately leads to more infrequent shopping trips and less purchase of produce due to in-store pricing [

28]. As the definition of food deserts evolves, it’s evident that the traditional grocery store measure does not account for the complexity of food access [

29]. Several studies have revealed that after food retail intervention projects, there is no significant impact on fruits and vegetable consumption [

30,

31]. In these studies, the perception of food access increased amongst community members, but their healthy food consumption remained unchanged [

30,

31]. From these studies it’s clear that a multidimensional approach to addressing food insecurity is necessary to incite change within a community, and that other factors besides the mere presence of healthy food in a community play a role in dietary habits and community health. Further continuing the development of a multidimensional approach, my study seeks to test the efficacy of using distance as a dimension to measure food insecurity, which is a crucial component of access to healthy food. In addition to this development, research shows that a combination of environmental factors in the community as well as widespread, equitable, education is necessary to influence behavior within a community [

32].

1.3. The Food Abundance Index

Researchers at the University of Pittsburgh developed a proprietary tool to measure regional food insecurity called the Food Abundance Index [

2]. This approach sought to capture the multidimensional nature of food insecurity in a community. The index assesses food security across five dimensions: Access, Affordability, Diversity, Density, and Quality [

2]. The access dimension scale examined the accessibility of local grocery stores via public transportation, where a grocery store with a bus stop within a quarter mile was considered to be accessible [

2]. Previous research used three of the five dimensions of the Food Abundance Index were assessed within the mid-Monongahela valley of Pittsburgh [

33]. This study revealed that there were a series of food outlets in Pittsburgh communities that did not have sufficient access via public transportation [

33]. This study also implicated that for future research, it is necessary to account for environmental structures like bridges and highways that may impede travel to grocery outlets [

33].

1.4. Elements of the Built Environment

Public transportation and environmental structures mentioned in this previous research are key elements of the built environment. The Environmental Protection Agency defines the built environment as “the man-made or modified structures that provide people with living, working, and recreational spaces,” which essentially encompasses the infrastructure of a community [

34]. An early study conducted on the connection between the built environment and obesity adopts the framework to define three different spaces within the built environment: the residential space, the activity space, and the connectors between these spaces [

35]. Expanding on this framework, a study exploring the relationship between the built environment and heart disease conducted in Australia examined the built environment across six dimensions: Density, Diversity, Design, Destination, Distance to Transit, and Demand Management [

36]. Research has indicated an association between obesity, specifically childhood obesity, and aspects of the built environment like walkability [

35,

37]. Food outlet access plays a role, as higher rates of obesity in children is seen in communities with more fast-food restaurants and convenience stores within walking distance of a residential neighborhood [

37]. The built environment has also been connected to the level of trust and collective efficacy within a community, where communities with more parks and less alcohol outlets were perceived to harbor more trust [

38]. Another study found a similar positive association between walkability and destination space access in a community to social capital, which is the prevalence of positive social relationships [

39]. Finally, research has shown that modifications to the built environment can contribute to eliminating disparities within a community, especially in the context of improving access to vital destination spaces like grocery stores, healthcare, and recreation [

40].

1.5. Purpose of this Study

This study is a comprehensive examination of the food system infrastructure in Allegheny County, assessing location trends in the establishment of key food outlet types like grocery stores and food banks. Also, our goal is to further explore the relationship between these food outlets and the public transportation system in Allegheny County. We focus on the accessibility of these food outlets by analyzing the walking distance from Port Authority public transportation stops to food outlets across four different categories. Ultimately, our goal is to determine if disadvantaged communities with food outlets that do not have public transportation stops within walking distance experience elevated levels of food insecurity. By examining the relationship between public transportation, walking distance, and food outlets, our goal is to develop a roadmap for researchers and policymakers to develop informed initiatives that address food access challenges in disadvantaged communities and address disparities that disproportionately impact women. This study will also critique existing methodologies regarding regional food system analysis and seek to identify areas where aggregate regional analysis using publicly available data may generate misleading insights. A case study of a vulnerable community in Pittsburgh will be leveraged to demonstrate the implications of this access assessment and demonstrate the link between women’s health and food access. Ultimately, the implications of this research will aid in more effective data collection and analysis of regional food systems in order to accurately capture disparities in disadvantaged communities in Allegheny County.

2. Methods

Our first analysis examines the food outlet landscape in Allegheny County with emphasis on areas that did not contain a particular type of food outlet. On a census tract level, the relationship between the presence of four different types of food outlets and the food insecurity rate was examined. The second analysis also focused on census tract levels, but instead focused on distances of public transportation stops to the food outlets in the area identified by the first analysis. Thus, we examined relevant demographic data and examined the correlation with high rates of food insecurity which were specific to the Larimer community within Allegheny County as a model that could be applied to the broader Pittsburgh community.

2.1. Data Acquisition and Cleansing

For this study, data was obtained from three primary outlets: the Western Pennsylvania Regional Data Center (WPRDC), the United States Census Bureau [

41], and Feeding America [

42]. The first group of data obtained from the WRPDC contained all the registered food outlets in Allegheny County [

43]. Classification of these food outlets was already established in the dataset, however only the classifications related to Grocery Stores (GS), Convenience Stores (CS), Food Banks (FB), and Farmer’s Markets (FM) were retained for the analysis. The classification was recoded from a previous delineation between chain and non-chain facilities, where chain and non-chain supermarkets were reclassified to be simply GS. This is the same, but more up-to-date, data that was used in the application of the Food Abundance Index to the Mid-Mon valley region in Pittsburgh [

33]. Food outlet licensing data as of June 2022 was used in this study. The second group of data from WRPDC contained all of the Port Authority Public Transportation stops in Allegheny County [

44]. This data primarily focused on ridership associated with the various Port Authority routes in the region. Our focus, however, was on extracting all of the stop locations in order to obtain a holistic view of the transportation environment in the region. Once every unique stop was obtained, data was synthesized with corresponding food outlet data. Using the Google Maps API in R, the closest public transportation stop to each food outlet was determined. Google Maps API was selected over other methods like the Euclidean distance due to the greater accuracy in the walkable path to the food outlet. Since Pittsburgh is a city of many bridges, there may be scenarios in which a public transportation stop would be close by as the crow flies, but in reality, the individual would have to take an alternative route in order to reach the food outlet. The use of the Google Maps API accounts for this as an approach to derive the distance of each route in meters, as well as the walking time in seconds. The master dataset contained each food outlet across the four categories and the closest public transportation stop. In order to determine the level of food insecurity for each census tract in Allegheny County, Feeding America’s “Map the Meal Gap” data was used for all of the census tracts in Pennsylvania. Feeding America uses a comprehensive methodology to estimate food insecurity rates based on a series of demographic variables [

42]. The Map the Meal Gap study is publicly available on a county level, but this census tract disaggregation is a specialized request completed by Feeding America using relevant regional data [

45]. Along with the estimate rates of food insecurity in each census tract in Pennsylvania, Feeding America also provided key demographic information related to food insecurity, like the percent of households enrolled the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. The final component of the analysis was to obtain key demographic information for each census tract in Allegheny County. For these metrics, the American Community Survey from the Census Bureau was queried for each and census tract in Allegheny County [

41]. From the 5-year estimate tables for 2021, key demographic factors like median household income and population were appended to the data provided by Feeding America. Feeding America uses the ACS data and the Food Security Supplement of the Current Population Survey to calculate the food insecurity rates, and as a result many demographic dimensions have strong correlation with the food insecurity estimates. In order to avoid multicollinearity, these demographic factors were not considered as predictors in any portion of the study.

2.2. Level of Analysis

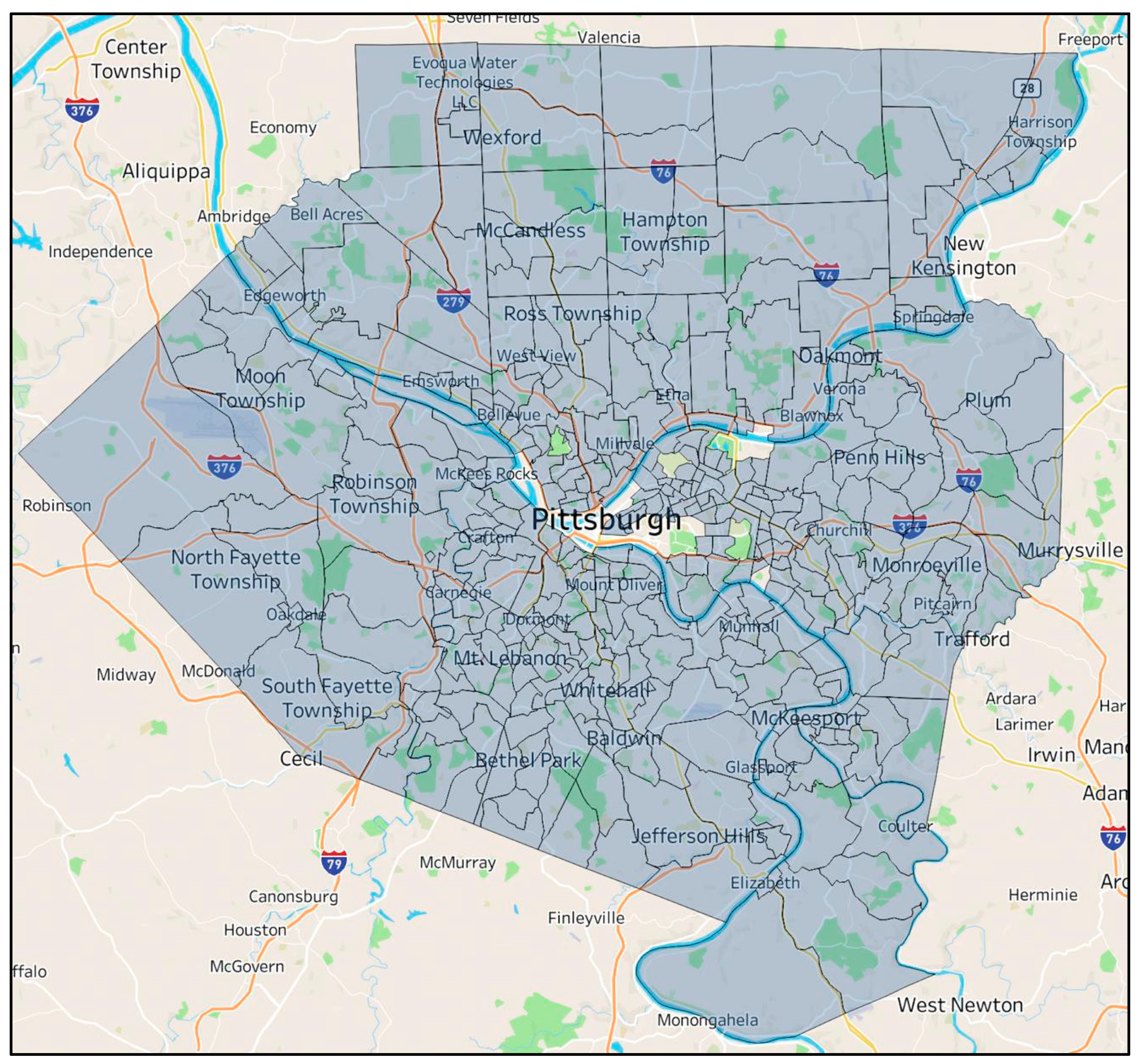

The level of analysis for the statistical analysis were census tracts. All census tracts in Allegheny County were included in the aggregate dataset, which was then filtered based on a series of parameters in order to reflect the region more accurately. All the census tracts that did not contain a sufficient population to produce a food insecurity estimate in Allegheny County were removed.

Appendix A lists the census tracts that were excluded from the statistical analysis.

Figure 1 depicts the census tracts that were included in the analysis for this study.

2.3. Examining the Food Landscape in Allegheny County

The purpose of this first analysis was to gain an understanding of the food outlet landscape in Allegheny County. Traditional methodologies to measure food insecurity have revolved around the presence of a food outlet in a community, but research has revealed that often this approach does not paint the entire picture of a community. However, to further explore the landscape of Allegheny County, the census tracts were first assessed for their overall classification and its relationship with the Feeding America rate of food insecurity. First, census tracts with high rates of food insecurity were identified and mapped. These maps were compared to the mapping of the population breakdown and median household income for each area. For each census tract, a binary classifier was appended to indicate the presence, or lack thereof, of each of the four food outlets at the focus of this study. In the first phase of this analysis, the data was separated into two parts: the tracts that had at least one of the respective food outlets and the tracts that did not. For example, one set contained census tracts that had a grocery store, and the other contained census tracts that did not. This was completed for all types of food outlets on the census tract level. This data was mapped in order to visualize areas in Allegheny County that lacked the basic presence of the four types of food outlets. Next, the average rate of food insecurity was calculated for each set of data, and a two-sample Welch t-test with a 95% confidence interval was used to determine if there was a significant difference in the mean rate of food insecurity of the two sets. Further statistical documentation on this analysis is available in Appendix B. The hypothesis for each test was that the mean rate of food insecurity does not differ between areas with and without each of the food outlets. We also examined whether the mean rate of food insecurity did differ between areas with and without each of the food outlets. The second phase of the analysis employed the same process, but the data was filtered to only incorporate census tracts that fell below the median household income of $69,091 in Allegheny County per the American Community Survey’s inflation-adjusted reporting for the current year. A trend in the data emerged that in high-income communities with low rates of food insecurity, the public transportation stops were a great distance from the food outlets. The assumption behind this trend is that in these communities, members are less likely to use public transportation to travel to a food outlet, and most likely own cars as a means of transportation, and the food outlets could be zoned for parking lots instead of public transportation access. The census tracts that fell below this median were subject to the same process as the first phase of the statistical analysis.

2.4. Examining Food Outlets and Public Transportation in Allegheny County

The second analysis conducted for this study delves further beyond only an assessment of the food outlets in Allegheny County to address the accessibility of these food outlets via public transportation, effectively incorporating one of the most important aspects of the built environment. The Food Abundance Index considers food outlets that have a public transportation stop greater than 0.25 miles away to be inaccessible and thus lowers the overall Food Abundance score for the region [

2]. This concept was used to determine the accessibility of food outlets in various census tracts in Allegheny County. Food outlets with a public transportation stop within 0.25 miles were considered accessible, while food outlets with a stop greater than 0.25 miles away were considered inaccessible. For each census tract, the minimum and average distance for each of the four food outlet classifications was calculated. We elected to use the minimum because this would theoretically represent the food outlet that is the most accessible via public transportation in terms of the stop proximity to the store. The census tracts were mapped based on the minimum and the average distances to the different types of food outlets. The statistical phase of the second analysis also involved the use of the two-sample Welch t-test with a 95% confidence interval to determine if there was a difference in mean rates of food insecurity in areas with accessible food outlets compared to those with inaccessible food outlets. This statistical test was first conducted on all the census tracts in the scope of the study, and then repeated using only census tracts below the Allegheny County median income. The first test incorporated only the minimum distances, while the analysis of the bottom 50% of areas examined both the minimum and average distances for each census tract.

2.5. Examining the Larimer Community within Allegheny County

Based on the previous analysis, a deeper dive into Allegheny County (census tract 120900) which is where the Larimer Neighborhood is located was conducted. Larimer currently experiences significant rates of food insecurity. Also, Larimer has a high proportion of female-headed households. The literature has revealed women, especially female heads of household, can experience disproportionate levels of food insecurity. Our analysis examined correlations between household type and food insecurity. A two-sample Welch t-test with a 95% confidence interval was conducted to determine if the average food insecurity rate differs at different proportions of female-headed households. Specifically, the census tracts were broken into two tranches. The first included all tracts where the proportion of female-headed households was above 14.3%, which is the average for Allegheny County. The second tranche is all tracts below this average. The t-test was used to determine if there was a significant difference in average rates of food insecurity between the two tranches of data.

3. Results

3.1. Food Insecurity Rates

Of the census tracts selected for the analysis, 63% did not contain a grocery store.

Table 1 depicts the results of the statistical analysis on the comparison of average food insecurity rates for all census tracts in the analysis.

Based on the results of the first analysis, census tracts with grocery stores and farmers markets had marginally lower rates of food insecurity, but these differences were deemed insignificant. There was a statistically significant difference in the average rate of food insecurity in tracts with and without food banks. Census tracts without food banks had lower rates of food insecurity. Based on this analysis, we also examined food insecurity for tracts that were below the median income within Allegheny County.

In census tracts without a grocery store, there was a statistically significantly higher rate of food insecurity when compared to tracts without any grocery stores present. For tracts without food banks there were statistically significant lower rates of food insecurity. Tracts with farmers' markets or convenience stores also had higher rates of food insecurity, but this difference was not found to be statistically significant.

3.2. Examining Public Transportation and Food Access Proximity

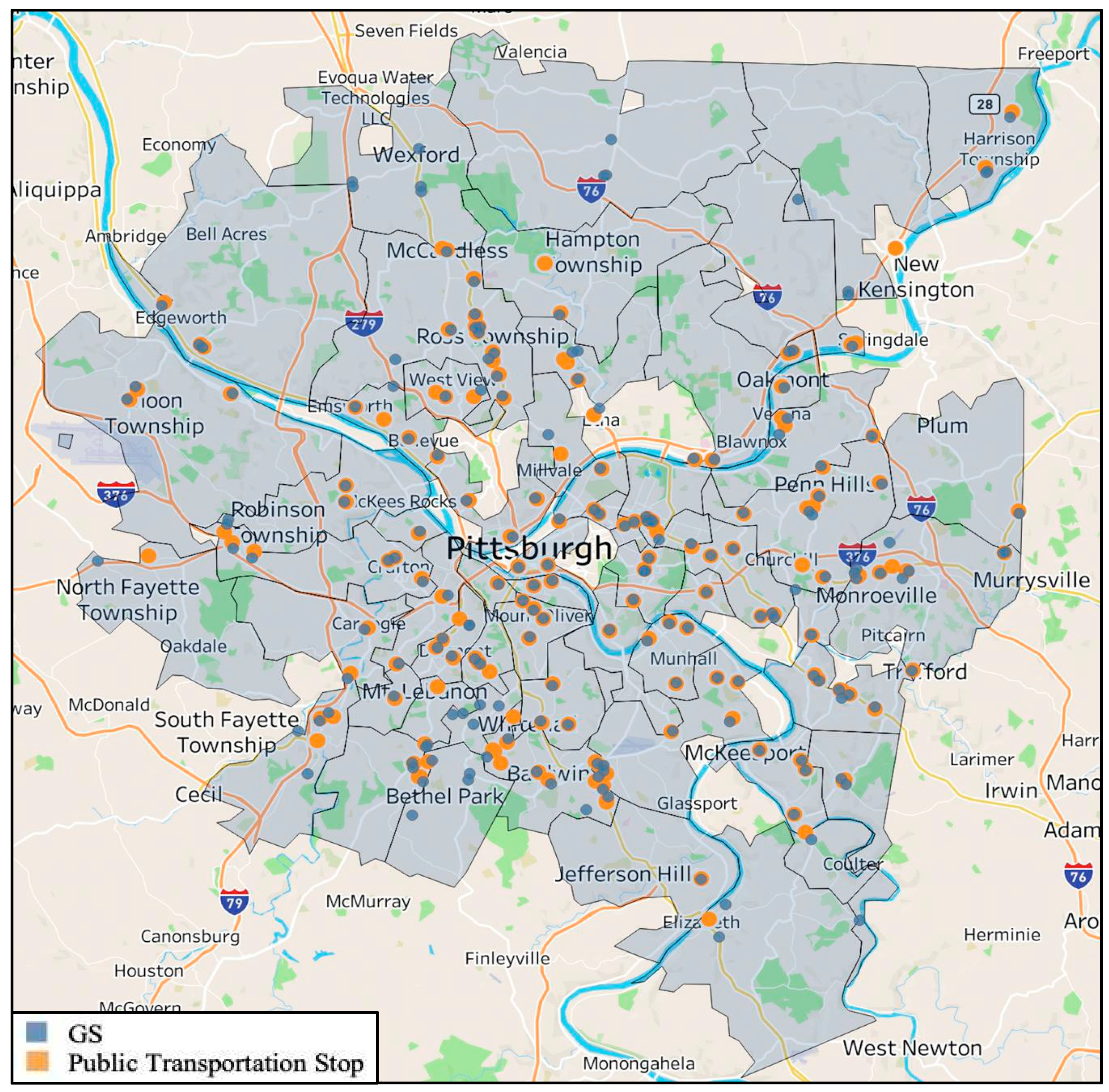

The mere presence of a grocery store or a particular food outlet in a community is not holistically indicative of the food security environment of the area. In order to gain a better understanding of this environment along the dimension of public transportation, census tracts were further divided based on the proximity of the food outlet in the community to public transportation stops.

Figure 2 portrays a map of the census tracts selected for the study and all of the grocery stores listed in the Allegheny County database.

Appendix B contains this analysis for the other three food outlet types. For each grocery store, a second point represents the closest public transportation stop by walking distance. Beginning with the minimum distance for each census tract, we conducted an analysis of the accessibility of the food outlets for all tracts selected as meeting the criteria for this study.

Table 3 displays the results for this analysis, all of which were statistically significant.

In census tracts where the closest grocery store was inaccessible by public transportation, there was determined to be a lower overall average rate of food insecurity. In fact, for every outlet type, the tracts where the closest outlet was inaccessible had lower rates of food insecurity. In order to account for income differences,

Table 4 displays the same analysis of minimum distance, however only the census tracts below the median income for Allegheny County were included.

The same trend, however, was determined in this analysis, where the average rate of food insecurity was lower for tracts with food outlets that were inaccessible. This comparison was only significant for grocery stores and convenience stores. It is important to note that when filtered by income, the average rate of food insecurity for tracts with inaccessible grocery stores increased substantially. This may signal a more significant and negative impact for low-income communities when a lack of food access and limited transportation are both present.

Table 5 depicts the distance analysis on the census tract level but instead aggregated by the average distance from food outlets to public transportation.

No statistically significant differences were found in the average rates of food insecurity for either classification across all four of the food outlet categories. However, tracts with grocery stores and food banks that were on average, inaccessible, did have marginally higher rates of food insecurity.

3.3. Examing Food Insecurity and Transportation Access for the Larimer Comunity

We specifically examined distance data for the Larimer neighborhood using the same approach as was conducted for Allegheny County overall. Prior to the 1960s, Larimer was a flourishing community, known as Pittsburgh’s “Little Italy.” In the 1960s, the neighborhood experienced significant “white flight,” as residents moved to the suburbs and businesses closed down [

46]. “White flight” is the exodus of white Americans from a neighborhood in the 1960s and 1970s as a result of desegregation of schools and an increase in African American families in urban neighborhoods [

47]. One study found that on a census tract level, an increasing proportion of African Americans was a significant predictor of white mobility [

48]. Interestingly, recent revitalization projects in the Larimer community that were put into place recently have been driven by current residents who advocate for housing, business development and greater food access. These efforts yielded a

$30 million grant from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development primarily focused on affordable housing development while issues related to food access are still an unaddressed priority in the community [

46].

Feeding America’s Map the Meal Gap study estimates that 23% of Larimer’s 1,728 residents experience food insecurity, which is over double the average rate of food insecurity for census tracts in Allegheny County. According to the U.S. Census, Larimer has an average household income of $20,000, which is one third of the average household income for Allegheny County. A majority of these households in the Larimer neighborhood are female headed, which is defined by the Census as a household with a single female head with either relative or nonrelative dependents. Based on the review of the literature, it is evident that women, particularly women who are head of household, experience a disproportionate level of food insecurity. This trend appears to be true, not just in the Larimer neighborhood, but in Allegheny County holistically.

In an assessment of all census tracts selected for this study, correlation was calculated between the rate of food insecurity for each tract and the proportion of households in the tract that were female headed. Other than female headed, a household can be classified as male headed, married couples, or non-family households. There is a significant positive correlation (0.74) between rates of food insecurity and proportion of female headed households among all census tracts for which there exists data in Allegheny County. A positive and signficant correlation was also found for male-headed households in Allegheny County, but significantly weaker compared to female-headed househols.

3.4. Examining Food Insecurity for Female-Headed Households in the Larimer Community

As depicted in

Table 6, the census tracts were classified into the two aforementioned categories: tracts with a proportion of female-headed households above and below the Allegheny County average proportion. After creating these two categories, we examined any differences in household composition and food insecurity rates. Tracts with above average proportion of female-headed households had significantly higher average rates of food insecurity. This significant difference was more pronounced when examining only census tracks below the median income within Allegheny County. Clearly, the combination of low median income and female-headed households has a significant impact on food insecurity rates within this community.

When examining only census tracts in Allegheny County without grocery stores, the largest difference in the average rate of food insecurity was examined. Census tracts that have an above-average proportion of female-headed households and no grocery store experienced 2.3 times the rate of food insecurity when compared to tracts with no grocery store with a below-average proportion of female-headed households. A similar trend existed with tracts that did have a grocery store. Areas (census tracts) that had an above-average proportion of female-headed households and a grocery store experienced 1.8 times the rate of food insecurity when compared to tracts with a grocery store with a below-average proportion of female-headed households. When controlling for income factors, the same trend was found in census tracts with and without grocery stores below the median income in Allegheny County. Census tracts that have an above-average proportion of female-headed households and no grocery store experienced 2.3 times the rate of food insecurity when compared to tracts with no grocery store with a below-average proportion of female-headed households. Thus, census tracts with an above-average proportion of female-headed households experienced higher rates of food insecurity.

4. Discussion

Based on this analysis, it is evident that there are still areas in Allegheny County that do not have a local grocery store for community members to access. In accordance with traditional food desert research, these areas have higher average rates of food insecurity. From the results of the statistical analysis regarding transportation, it was determined that there is only a weak relationship between distances to public transportation stops and rates of food insecurity. This finding must be interpreted with caution because it is widely known that improving physical access to food, especially in the context of affordable transportation, enables members of marginalized communities to access healthy, sustainable food. Ironically, significantly higher rates of food insecurity were present in communities with higher perceived access to food. Perhaps the solution to reducing the negative impact on well-being especially for female-headed households is to examine a more comprehensive definition of food access rather than the mere presence of a single food outlet or grocery store. While this study examined transportation access, there was limited data available for determining how individuals and families used alternate methods of transportation to obtain food (e.g., car pooling, food delivery, community pick-up points). For this study, these unexamined and perhaps confounding variables that may be difficult to measure could influence the results. These variables could be labeled the “re-built” environment as they reflect the ways in which families especially those female-headed households adjust and cope with lack of access to both food and transportation resources. For example, while often not considered to be a standard food outlet, there was a significant relationship between convenience store accessibility and food access. Unfortunately, these types of food outlets can increase food insecurity since the quality of food available is not considered healthy or affordable.

Within the current study, neighborhoods with more accessible convenience stores were found to have significantly higher rates of food insecurity, which corroborates the notion of food swamps, where there is a high level of access to unhealthy, innutritious food options [

49]. When examining the mapping of the convenience stores compared to the public transportation stops, it seems that the convenience stores were poised at locations that followed the mapping of the transit system. Another trend that emerged was the clustering of mid-urban areas that had lower access to grocery stores via public transportation and higher rates of food insecurity. It was determined that areas experiencing severe poverty within the urban environment had high rates of food insecurity but also high access to public transportation. On the other end of the spectrum, areas in a suburban environment with low rates of food insecurity had low access to public transportation, presumably because many residents had access to private cars. The key areas experiencing marginalization in the context of this study were a collection of mid-urban areas with high rates of food insecurity and low access to public transportation that have a disparately negative impact on overall well-being.

Another group determined to be experiencing a disproportionate rate of food insecurity, compounded by a lack of access to food, were areas with a high proportion of female headed households. While throughout all scopes of the analysis, areas with high proportions of female-headed households experienced significantly higher food insecurity rates on average, areas without a local grocery store experienced the most significant and negative impact. This suggests that access to food, along with income demographics, may contribute to the disproportionately high rate of food insecurity that female-headed households face that have a negative impact on both their families and communities. Food insecurity is linked to greater prevalence of chronic disease and mental health issues, so this conclusion has important implications for women’s health and well-being. An improvement in financial support, enhanced access to affordable food sources, and well be improvements in transportation infrastructure may alleviate the additional burden for female headed households and address the disproportionate rates of food insecurity experienced and its negative impact on well-being.

There are some limitations with the type of regional analysis conducted in the current research that should be acknowledged. A food outlet could be situated on a border, being accessible to those in an area but not appearing in an analysis of presence. When conducting this style of analysis in the future, it may be more effective to use more advanced spatial regression techniques and data structures. Additionally, the incorporation of other variables may add greater insight into the accessibility of different food outlets in the region such as community-based solutions and alternatives. In addition, population density appears to play a role, as areas with high population density in Allegheny County have high access to public transportation stops. Additionally, incorporating the density of public transportation stops into the model would more effectively address disparities within each study area. For example, if a census tract does have a grocery store and a public transportation stop nearby, but a particular segment of that tract does not have any nearby stops, access for individuals within that segment may be limited. Incorporating density may provide a more holistic approach to examining the accessibility of public transportation and its impact on food access. Finally, Allegheny County has significant variation in topography (e.g., hills, wooded areas) which impacts the walkability of the routes from the public transportation stops to the food outlet but is somewhat difficult to measure based on existing technology. While a food outlet may appear to be a short distance away, this route could incorporate a hill or a steep incline, which is especially strenuous to navigate when carrying groceries. This is clearly an area for future research that can measure and include more specific data on topology as a factor along with distance.

5. Conclusions

The focus on the accessibility of food outlets should deviate from a holistic focus on distance calculation and instead focus on walkability. While large-scale data analysis of regional factors like the analysis conducted for this research is convenient and can garner some insight, it should not be used as the basis for policy and action. For these changes, it is crucial to avoid pure emphasis on distance and instead look at walkability. Distance analysis can be misleading when taken at face value. Instead, this distance analysis can be used as a roadmap for further investigation into key areas in need of support. Once disparities are identified through a distance analysis, grassroots data collection to gain a better understanding of the walkability and individual experience of community members is necessary to effectively address accessibility issues. Policy should be driven by walkability and qualitative analysis of the built environment of at-risk communities, not simply a distance calculation. Surveying methodology, especially when used in conjunction with regional analysis, can provide insight into consumer behavior and social trends in the region. In the context of transportation, research has found that people often travel outside of their own domain to go to preferred stores for food [

50]. For future analysis, the synthesis of individual behavior within a community, vehicle access, and walkability will provide greater insight into the accessibility of food outlets within a community especially for those families and communities that are most impacted by lack of food assess which is critical for overall health and well-being.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Alex Firestine and Audrey Murrell.; methodology, Alex Firestine and Audrey Murrell; formal analysis, Alex Firestine; resources, Audrey Murrell; data curation, Alex Firestine; writing—original draft preparation, Alex Firestine; writing—review and editing, Alex Firestine and Audrey Murrell; visualization, Alex Firestine; supervision, Audrey Murrell; project administration, Audrey Murrell. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge and express their gratitude to: Dr. Leon Valdes, Dr. Sabina Deitrick, Prof. Meredith Grelli, University of Pittsburgh, David C. Frederick Honors College and the members of the Food21 (

www.food21.org) organization for their help, support, guidance and expertise in making this project a reality.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Census Tracts Used in Analyses

| 42003010301, |

42003010302, |

42003020100, |

42003020300, |

42003040200, |

42003040500, |

| 42003040600, |

42003040900, |

42003051000, |

42003140100, |

42003515300, |

42003563201, |

| 42003980000, |

42003980100, |

42003980300, |

42003980400, |

42003980500, |

42003980600, |

| 42003980700, |

42003980800, |

42003980900, |

42003981000, |

42003981100, |

42003981200, |

| 42003981800, |

42003982200. |

|

|

|

|

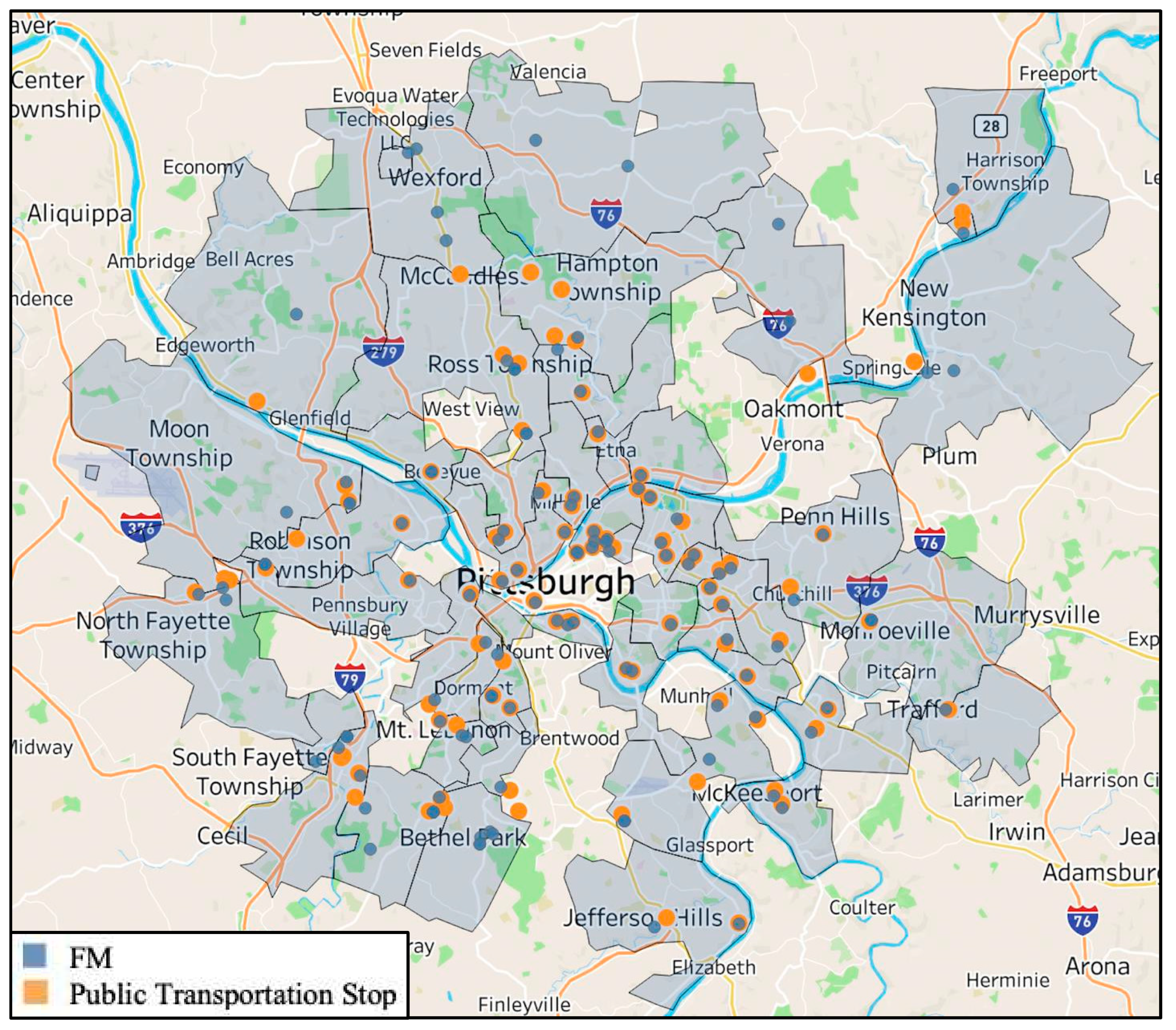

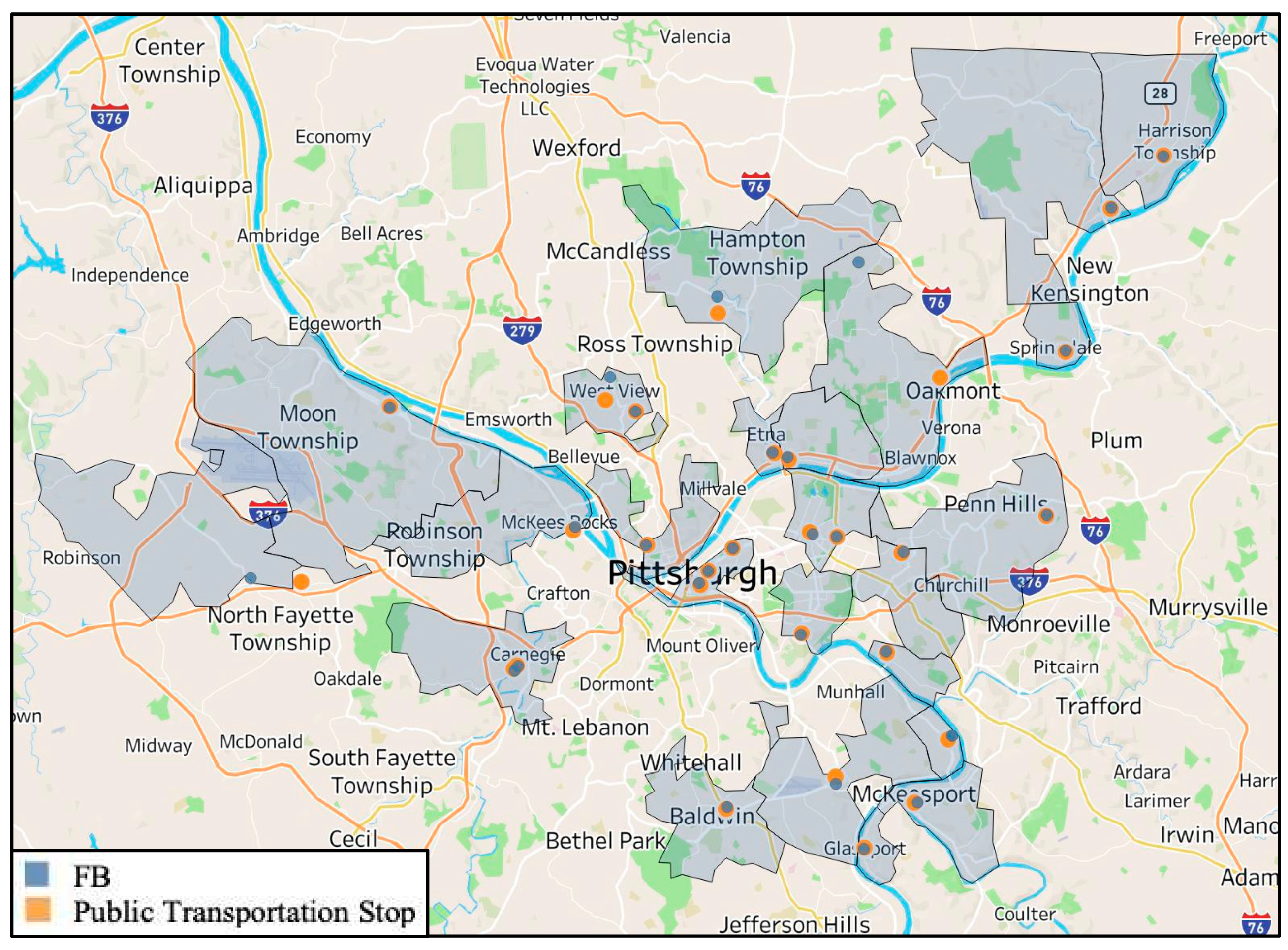

Figure B1.

Convenience Stores and Nearest Public Transportation Stop.

Figure B1.

Convenience Stores and Nearest Public Transportation Stop.

Figure B2.

Farmer’s Markets and Nearest Public Transportation Stop.

Figure B2.

Farmer’s Markets and Nearest Public Transportation Stop.

Figure B3.

Food Banks and Nearest Public Transportation Stop.

Figure B3.

Food Banks and Nearest Public Transportation Stop.

References

- Coleman-Jensen, A.; Rabbitt, M.; Hales, L.; Gregory, C. (2023). Food Security in the U.S. Economic Research Service; U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food- security-in-the-u-s/.

- Murrell, A.; Jones, R. Erratum: Murrell, A., et al. Measuring Food Insecurity Using the Food Abundance Index: Implications for Economic, Health and Social Well-Being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2434. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2020, 17, 6495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute for Local Self Reliance. (2018). Dollar store impact. https://ilsr.org/wp- content/uploads/2018/12/Dollar_Store_Fact_Sheet.pdf.

- Seligman, H.K.; Laraia, B.A.; Kushel, M.B. Food Insecurity Is Associated with Chronic Disease among Low-Income NHANES Participants. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laraia, B.A. Food Insecurity and Chronic Disease. Adv. Nutr. Int. Rev. J. 2013, 4, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- City of Pittsburgh. (n.d.). Food access programs. Retrieved , 2023, from http://pittsburghpa.gov/dcp/food-access-programs. 9 April.

- Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank. (2021). Hunger Profile: Allegheny County. https://pittsburghfoodbank.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/2021-Allegheny-County-hunger- profile.pdf.

- Gulish, B. (2020). Food Insecurity Rates Increase Significantly Due To COVID-19 Pandemic. https://pittsburghfoodbank.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/PRESS-RELEASE-New-Food- Insecurity-Data-Shows-Significant-Increase-in-Southwest-PA.pdf.

- Men, F.; Tarasuk, V. Food Insecurity amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: Food Charity, Government Assistance, and Employment. Canadian Public Policy / Analyse de Politiques 2021, 47, 202–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, N.M.; de Bairros, F.S.; Pattussi, M.P.; Pauli, S.; Neutzling, M.B. Gender differences in the prevalence of household food insecurity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Heal. Nutr. 2017, 20, 902–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, M. Compounding crises of economic recession and food insecurity: a comparative study of three low-income communities in Santa Barbara County. Agric. Hum. Values 2012, 29, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P.; Sachs, C. Women and Food Chains: The Gendered Politics of Food. Int. J. Sociol. Agric. Food 2007, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.M.; Sharkey, J.R.; Lackey, M.J.; Adair, L.S.; E Aiello, A.; Bowen, S.K.; Fang, W.; Flax, V.L.; Ammerman, A.S. Relationship of food insecurity to women’s dietary outcomes: a systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 2018, 76, 910–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papan, A.S.; Clow, B. The food insecurity―obesity paradox as a vicious cycle for women: inequalities and health. Gend. Dev. 2015, 23, 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, M.; Uphoff, E.; Kelly, B.; E Pickett, K. Food insecurity and mental health: an analysis of routine primary care data of pregnant women in the Born in Bradford cohort. J. Epidemiology Community Health 2017, 71, 324–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsey-Priebe, M.; Lyons, D.; Buonocore, J.J. COVID-19′s Impact on American Women’s Food Insecurity Foreshadows Vulnerabilities to Climate Change. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 6867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, J.G.; Russomanno, J.; Tree, J.M.J. Sexual orientation disparities in food insecurity and food assistance use in U.S. adult women: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2005–2014. BMC Public Heal. 2020, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman-Jensen, A.; Rabbitt, M.P.; Gregory, C.A.; Singh, A. (2022). Household Food Security in the United States in 2021, ERR-309. Economic Research Service; U.S. Department of Agriculture. ttps://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/104656/err-309.pdf?v=7320. 7320. [Google Scholar]

- Whitacre, P.; Yih, P.T.; Mulligan, J.; Institute of Medicine (U.S.); National Research Council (U.S.); National Research Council (U.S.) (Eds.) (2009). The public health effects of food deserts: Workshop summary. National Academies Press.

- Karen Washington. (n.d.). Rise & Root Farm. Retrieved , 2023, from https://www.riseandrootfarm.com/karen-washington. 5 April.

- Brones, A. (2018, May 15). Food apartheid: The root of the problem with America’s groceries. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/may/15/food-apartheid-food-deserts- racism-inequality-america-karen-washington-interview.

- Burns, C.; Inglis, A. Measuring food access in Melbourne: Access to healthy and fast foods by car, bus and foot in an urban municipality in Melbourne. Heal. Place 2007, 13, 877–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ball, K.; Timperio, A.; Crawford, D. Neighbourhood socioeconomic inequalities in food access and affordability. Heal. Place 2009, 15, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Union of Concerned Scientists. (2016). The Devastating Consequences of Unequal Food Access: The Role of Race and Income in Diabetes. Union of Concerned Scientists. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep17305.

- Bower, K.M.; Thorpe, R.J., Jr.; Rohde, C.; Gaskin, D.J. The intersection of neighborhood racial segregation, poverty, and urbanicity and its impact on food store availability in the United States. Prev. Med. 2014, 58, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskin, D.J.; Thorpe, R.J., Jr.; McGinty, E.E.; Bower, K.; Rohde, C.; Young, J.H.; LaVeist, T.A.; Dubay, L. Disparities in Diabetes: The Nexus of Race, Poverty, and Place. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 2147–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breyer, B.; Voss-Andreae, A. Food mirages: Geographic and economic barriers to healthful food access in Portland, Oregon. Heal. Place 2013, 24, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, M. acticing anthropology on a community-based public health coalition: Lessons from heal. Ann. Anthr. Pr. 2011, 35, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedore, M. Geographies of capital formation and rescaling: A historical-geographical approach to the food desert problem: Geographies of capital formation and rescaling. The Canadian Geographer / Le Géographe Canadien 2013, 57, 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, R.C.; Gilliland, J.A.; Arku, G. A Food Retail-Based Intervention on Food Security and Consumption. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2013, 10, 3325–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, S.; Flint, E.; Matthews, S.A.; Zenk, S.N.; Tarlov, E.; Wing, C.; Jones, K.; Tong, H.; Powell, L.M.; Shannon, J.; et al. New Neighborhood Grocery Store Increased Awareness Of Food Access But Did Not Alter Dietary Habits Or Obesity. Heal. Aff. 2014, 33, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, R.C.; Gilliland, J.A.; Arku, G. Theoretical issues in the “food desert” debate and ways forward. GeoJournal 2016, 81, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murrell, A.J.; Jones, R.; Rose, S.; Firestine, A.; Bute, J. Food Security as Ethics and Social Responsibility: An Application of the Food Abundance Index in an Urban Setting. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 10042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US EPA. (2017). Basic information about the built environment. https://www.epa.gov/smm/basic- information-about-built-environment.

- Papas, M.A.; Alberg, A.J.; Ewing, R.; Helzlsouer, K.J.; Gary-Webb, T.L.; Klassen, A.C. The Built Environment and Obesity. Epidemiol. Rev. 2007, 29, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Hooper, P.; Javad Koohsari, M.; Foster, S.; Francis, J. (2014). Low density development: Impacts on physical activity and associated health outcomes. https://resources.heartfoundation.org.au/images/uploads/publications/Heart_Foundation_Low_de nsity_Report_FINAL2014.pdf.

- Le, H.; Engler-Stringer, R.; Muhajarine, N. Walkable home neighbourhood food environment and children’s overweight and obesity: Proximity, density or price? Canadian Journal of Public Health / Revue Canadienne de Santé Publique 2016, 107, eS42–eS47. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/90006797. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.A.; Inagami, S.; Finch, B. The built environment and collective efficacy. Heal. Place 2008, 14, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumdar, S.; Learnihan, V.; Cochrane, T.; Davey, R. The Built Environment and Social Capital: A Systematic Review. Environ. Behav. 2018, 50, 119–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutch, D.J.; Bouye, K.E.; Skillen, E.; Lee, C.; Whitehead, L.; Rashid, J.R. Potential Strategies to Eliminate Built Environment Disparities for Disadvantaged and Vulnerable Communities. Am. J. Public Heal. 2011, 101, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Census Bureau. (2021). American Community Survey. [Data set]. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs.

- Feeding America. (2022). Map the Meal Gap 2022 Technical Brief. https://www.feedingamerica.org/sites/default/files/2022- 08/Map%20the%20Meal%20Gap%202022%20Technical%20Brief.pdf?s_src=W233REFER&s_ referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fmap.feedingamerica.org%2F&s_channel=https%3A%2F%2Fmap.feedingamerica.org%2F&s_subsrc=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.feedingamerica.org%2F%3F_ga%3D2.184580201.1333710483.1679974539-31638797.1675470498.

- Western Pennsylvania Regional Data Center. (2022). Allegheny County Restaurant/Food Facility Inspections and Locations. [Data set]. https://data.wprdc.org/dataset/allegheny-county-restaurant- food-facility-inspection-violations.

- Western Pennsylvania Regional Data Center. (2022). Port Authority Monthly On Time Performance by Route. [Data set]. https://data.wprdc.org/dataset/port-authority-monthly-average-on-time- performance-by-route.

- Gundersen, C.; Strayer, M.; Dewey, A.; Hake, M.; Engelhard, E. (2022). Map the Meal Gap 2022: An Analysis of County and Congressional District Food Insecurity and County Food Cost in the United States in 2020. Feeding America.

- Davison, R. (2019, November 20). ‘We deserve it’: Larimer residents reflect on the neighborhood’s history and the long fight for redevelopment. PublicSource. http://www.publicsource.org/we-deserve-it-larimer-residents-reflect-on-the-neighborhoods-history-and-the-long-fight-for-redevelopment/.

- Krysan, M. Whites Who Say They'd Flee: Who Are They, and Why Would They Leave? Demography 2002, 39, 675–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowder, K. The Racial Context of White Mobility: An Individual-Level Assessment of the White Flight Hypothesis. Soc. Sci. Res. 2000, 29, 223–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooksey-Stowers, K.; Schwartz, M.B.; Brownell, K.D. Food Swamps Predict Obesity Rates Better Than Food Deserts in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2017, 14, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, C.; Tomer, A. (2021). Beyond ‘food deserts’: America needs a new approach to mapping food insecurity. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/research/beyond-food-deserts-america- needs-a-new-approach-to-mapping-food-insecurity/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).