1. Introduction

Bladder cancer (BC) is the most common malignancy of the urinary system [

1]. At present, the most common treatment approach for BC is still transurethral resections of the bladder tumour (TURBT) and intravesical drug delivery (IDD) of Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) [

2]. However, these treatments have a high recurrence rate and a severe risk of progression remains. Recently, PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors and FGFR inhibitors have been approved for BC, but potential side effects and the low response ratio of these drugs have restricted their clinic application [

3]. Thus, novel therapeutic approaches are urgently required.

Metformin (Met,

SFig. 1) has been a first-line oral hypoglycaemic agent for treatment of type 2 diabetes (T2D) for decades, and its potential association with decreased cancer risk and improved cancer prognosis Has aroused increasing attention [

4]. However, according to the results of multiple clinical trials, metformin has not been effective in inhibiting the proliferation and growth of the tumour cells if taken orally [

5,

6,

7]. It has been speculated that the low clinical anticancer responses of metformin is because of the circulating concentration in the body being low following conventional drug delivery, failing to achieve a sufficient dose to kill the tumour cells. The unique physiological features of the bladder allow intravesical administration of metformin, which can enhance the anti-tumour concentration locally [

8]. However, intravesical administration has inherent limitations since the delivered drugs may be diluted and discharged easily in the urine [

9]. Consequently, to attain an effective concentration, repeated intubation is acquired, which puts patients at increased risk of infection and inconvenience. Reducing the dose and increasing the retention time on the bladder surface remains a challenge.

Chitosan (Cs) is a nature-derived mucopolysaccharide primarily attained from the deacetylation of chitin [

10,

11,

12]. In recent years, benefiting from its nanometric size, biodegradability, virulence, and biocompatibility, Cs has been used as an effective carrier for drug delivery systems [

13]. It has been shown that Cs possesses the advantages of controlling drug release, prolonging drug efficacy, and reducing side effects of the drugs, which are helpful for improving stability and permeability through the cell membrane [

14]. Cs-based gels and nanoparticles have been used to deliver various different therapeutic agents, including peptides, small molecules, vaccines, DNA, and drugs [

15,

16]. Thus, considering that Cs dramatically improved the performance of mucoadhesive vaginal gels [

17,

18,

19,

20], developing novel formulations using Cs as a carrier for treating BC has a significant potential in anti-BC drug development. Additionally, Cs carries a positive charge, which can interact with the mucous membranes of the bladder so as to enhance the duration of metformin in the bladder, promoting the absorption of hydrophilic drugs [

21,

22].

Continuing previous observations regarding the potential for treatment of BC with metformin [

8,

23,

24], the present study prepared metformin-loaded Cs hydrogels, (MLCH) using freeze-drying to enhance the bioavailability of the metformin when intravesically administered. Moreover, a cell culture model was used to determine the optimized formulation. An orthotropic animal bladder tumour model, which simulates the occurrence and development of human BC [

25], was used to evaluate the efficiency of this newly prepared MLCH formulation. Significantly, based on previous explorations of the molecular mechanism of metformin [

23,

24], the functional activation of the AMPK/mTOR signalling pathway was determined using both in vitro and in vivo samples. The present study may pave the way for exploring the development of a safe and highly efficient formulations of Met for clinical use in the treatment of BC.

2. Results

2.1. Freeze-Drying Improves the Microstructure of Cs and Induces the Formation of Colloidal Hydrogels

The transmittance measured by UV-vis spectrophotometry is typically used for evaluating the degree of turbidity [

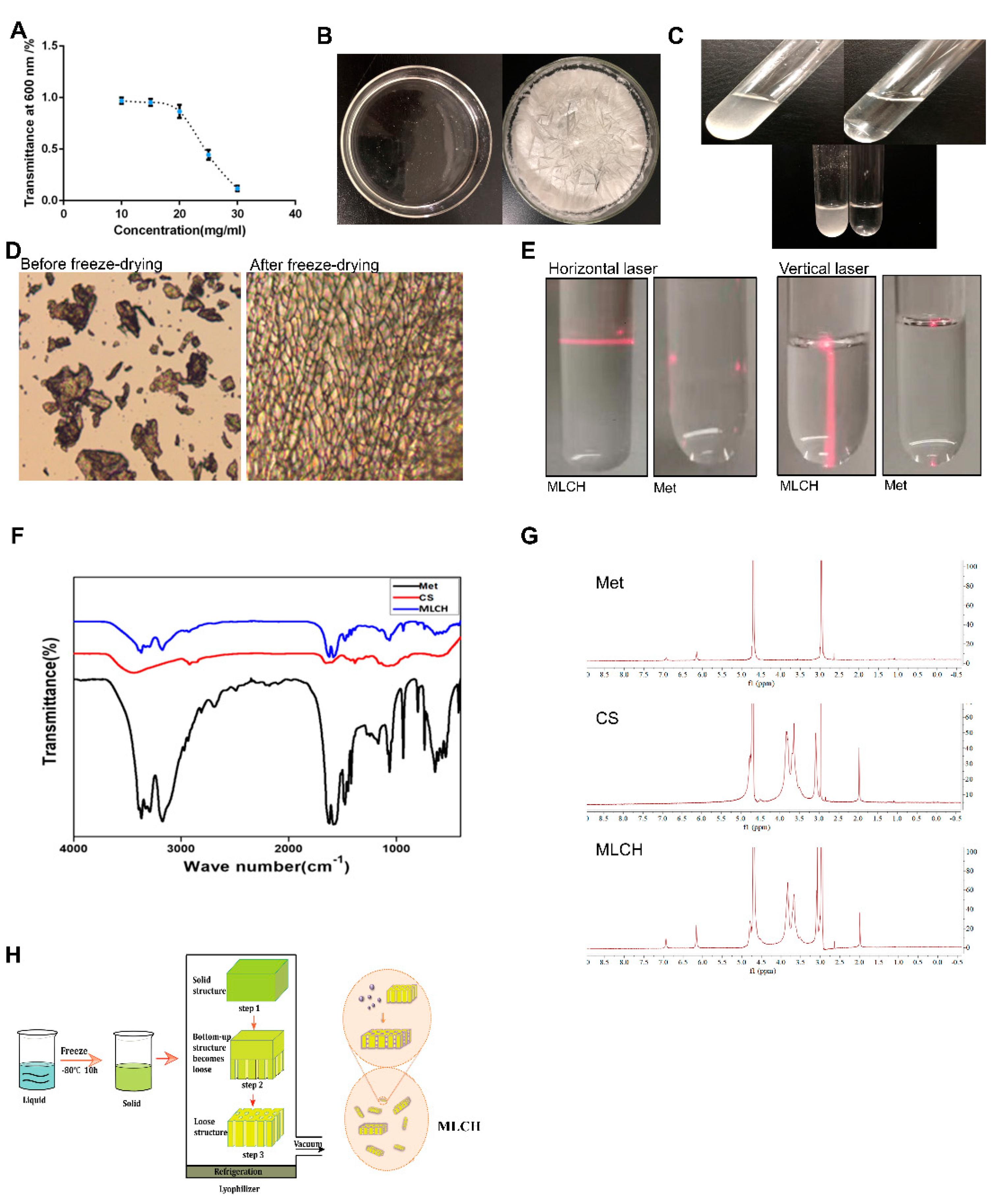

26]. As shown in

Figure 1A, the transmittance of Cs (10–20 mg/ml) in hydrochloric acid solution was close to 90%, indicative of a high degree of transparency. In contrast, its light transmittance reduced sharply by 40–50% at concentrations of 20–25 mg/ml. This demonstrated that the amine groups on Cs formed a salt with the hydrogen ions in the acid, such that the original hydrogen bond of the Cs was destroyed and dissolved. Therefore, a hydrochloric acid solution with a Cs concentration of 10 mg/ml was used for freeze-drying. As shown in

Figure 1B, right panel, uniform lyophilized Cs powder was obtained after freeze-drying. Compared with the regular Cs powder, which is almost insoluble in Met-containing physiological saline, the equivalent quantity of lyophilized Cs powder was completely dissolved (

Figure 1C), indicating a notable increase in solubility following the freeze-drying procedure. Furthermore, the lyophilized Cs powder displayed a well arranged, finely networked structure, in contrast to the disordered structure of regular Cs powder (

Figure 1D), demonstrating a notable improvement in the microstructure following freeze-drying. In addition, the Tyndall effect assay indicated that only MLCH showed a significant Tyndall effect (

Figure 1E), demonstrating its colloidal characteristics. Subsequently, we used infrared spectral to determine whether Cs and metformin formed intermolecular chemical bonds or Cs served as carrier to load metformin. As shown in

Figure 1F, the absorption peaks of Met at 3368 and 3292 cm

-1 represented the asymmetric and symmetrical stretching vibration of -NH. The absorption peak at 3150 cm

-1 was the stretching vibration absorption peak of -NH, and the absorption peak at 1621 cm

-1 was the stretching vibration of C=N. The double absorption peaks at 1472 and 1446 cm

-1 were the symmetric bending vibration absorption peaks of the methyl CH groups, indicating that there were no significant differences amongst the characteristic peaks between the infrared spectra of MLHC and Met. In addition, NMR hydrogen spectra proved that no new peaks were generated (

Figure 1G). All these results showed that MET wrapped in loose and porous Cs rather than formed intramolecular chemical bonds between MET and Cs (

Figure 1H).

2.2. MLCH Exhibits Favourable Physical and Chemical Properties, and Can Be Administered Intravesically

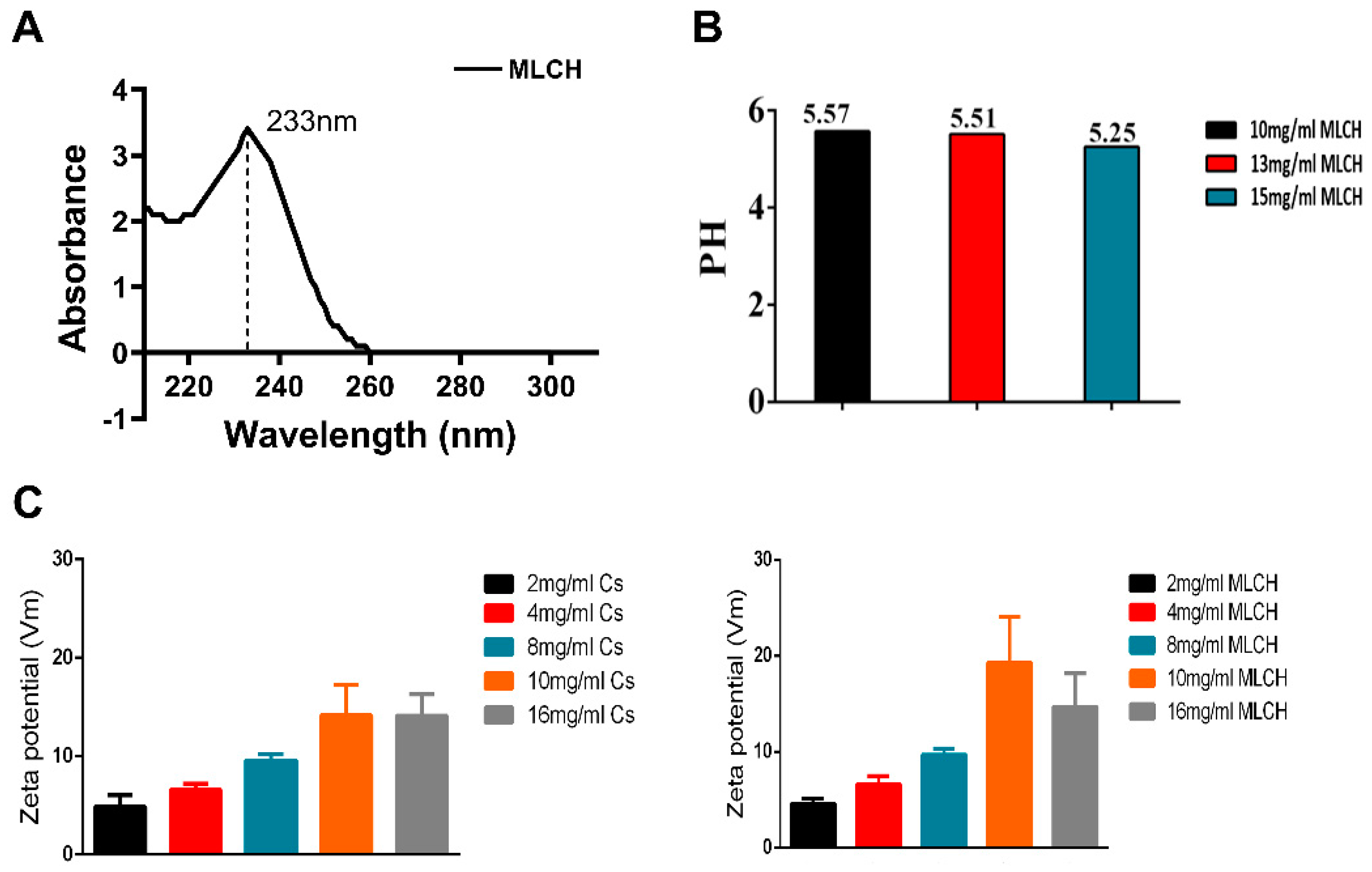

In order to obtain the optimal MLCH, the features of MLCH prepared with different concentrations of Cs were detected. The UV spectrum of MLCH displayed a characteristic absorption peak at 233 nm, indicating the presence of Met (

Figure 2A). Moreover, the pH of MLCH was ~5, meeting the requirements for bladder perfusion (

Figure 2B).

The ζ potentials of all MLCH solutions were positive due the presence of the positively charged carbohydrates of Cs (

Figure 2C). Of note, addition of Met increased the ζ potential value (

Figure 2C, right panel) compared with the Cs hydrogel alone (

Figure 2C; left panel), indicating a favourable physical interaction between Met and lyophilized Cs hydrogel. More importantly, a maximum ζ potential was obtained when 10 mg/ml of lyophilized hydrogel was used, demonstrating the optimum physical interaction between these two substances (

Figure 2C). High ζ potentials favour adherence of a drug to the negatively charged bladder membrane (

Figure 2C). All these results indicated that 10 mg/ml of CS was the most suitable vector for metformin.

2.3. MLCH Shows a Robust Inhibitory Effect against BC Cell Growth In Vitro

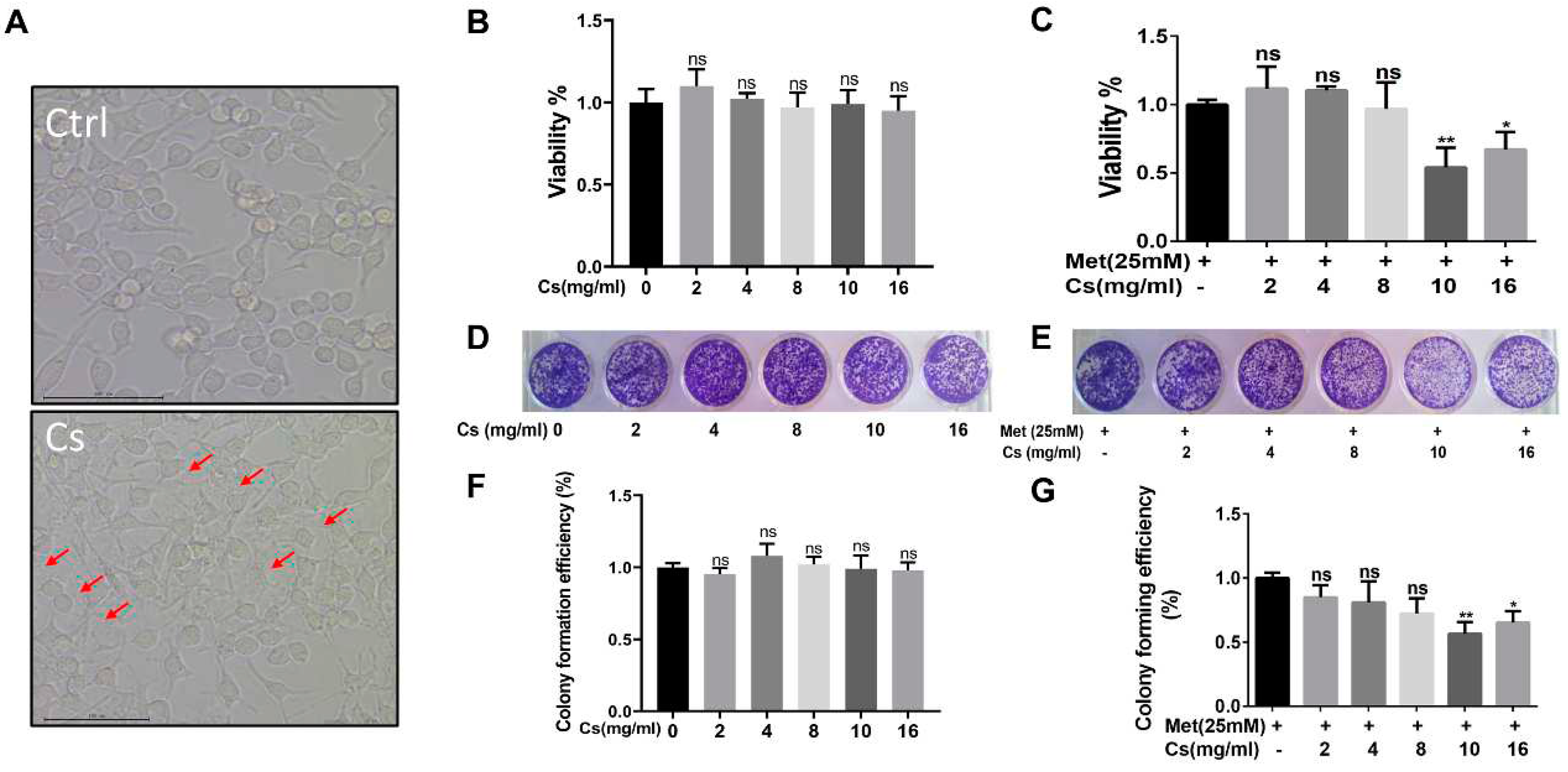

The next question was whether the MLCH prepared at 10 mg/ml of Cs had the best antitumor effect. Since MB49 is one of the most commonly used murine BC cell lines for establishment of an orthotopic BC model in immune complete mice, the inhibitory effect of MLCH was assessed using this cell line. As shown in

Figure 3A, after removing the culture medium, the Cs shell adhered to the cells. The Cs had no inhibitory effect on the growth of tumour cells, indicating that Cs had good adhesion and safety. The optimal ratio of MLCH was assessed using MTT assays. Cell viability was assessed via treatment with Cs hydrogel alone or with MLCH formulations of different Cs concentrations for 2 h. As shown in

Figure 3B, the Cs hydrogels alone did not inhibit the growth of tumour cells, indicative of their low toxicity. In contrast, MLCH exhibited a potent inhibitory effect against cell viability. Moreover, there were significant differences in cells treated with MLCH via 10 mg/ml Cs hydrogels, MLCH via 16 mg/ml Cs hydrogels, and Met alone, at all detected amounts, in MB49 cells. Notably, MLCH in 10 mg/ml Cs hydrogel exhibited the best inhibitory effect (

Figure 3C), and thus, this ratio of Cs hydrogel:Met was considered optimal. Furthermore, colony formation assays showed that MLCH in 10 mg/ml Cs hydrogels exhibited the optimum anticancer activity, in agreement with the MTT assay (

Figure 3D–G). Taken together, these data provide solid evidence that 10 mg/ml Cs prepared MLCH had the best anticancer activity.

2.4. Intravesical Treatment of MLCH Possesses Potent Anticancer Effects In Vivo

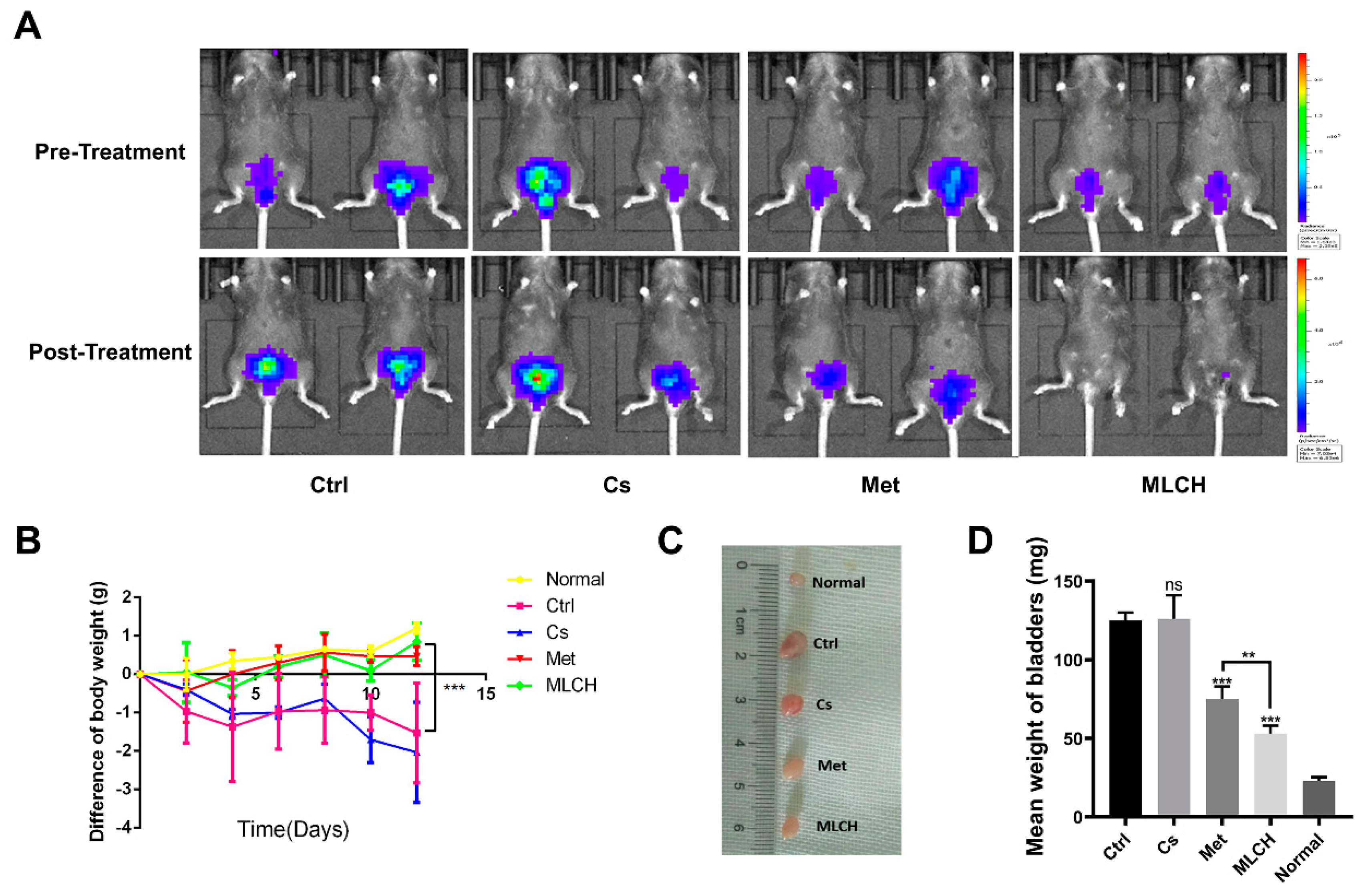

Orthotopic mouse tumour models are useful tools to assess the effects of intravesical localized treatments [

27]. The anti-tumour activity of MLCH were assessed in vivo using a well-established orthotopic tumour mouse model [

28,

29,

30]. Met alone exhibited significant inhibitory effects against bladder tumour growth compared with the control mice. MLCH demonstrated a more potent inhibitory effect against bladder tumour growth compared with Met alone, demonstrating the beneficial effects of the novel formulation for BC treatment in vivo. No obvious inhibitory effects against bladder tumour growth were observed in the Cs group (

Figure 4A). During the course of the animal experiments, the total body weight of the animals was monitored to assess whether any of the treatments exerted any toxic effects. Consistent with the in vitro experiments, mice with orthotopic tumours that were not treated with Met or MLHC exhibited significant decreases in body weight due to the tumour, and they were immediately euthanized when the maximum weight loss of the mice exceeded 20%. The decrease in body weight caused by BC was alleviated in the Met group. Consistent with the results of the MTT assay, in the Cs group, the body weight decreased in a manner similar to that observed in the control group; thus, Cs hydrogel alone did not exert any beneficial effects. Intravesical administration of MLCH and Met resulted in significant alleviation of the decrease in body weight (

Figure 4B). In addition, as shown in

Figure 4C,D, the heaviest bladders were measured in the control and Cs groups due to the formation of the tumours. In contrast, the bladder weights in both the Met and MLCH groups were significantly lower compared with the control and Cs groups, and the reduction was greater in the MLCH group.

Taken together, MLCH displayed excellent antitumor effects, as demonstrated by the inhibition of growth of orthotopic tumours, improvement in whole body weight, and attenuation of the tumour-induced increase in bladder weight.

2.5. MLCH Increases Phosphorylation of AMPK in BC Tissues

It is well established that the anticancer activity of Met is mediated by its ability to activate the AMPK pathway [

31,

32]. By examining the levels of p-AMPK and its downstream proteins, including p-mTOR, p-P70s6k, and p-4Ebp1, it was found that MLCH significantly increased the phosphorylation of AMPK and reduced the phosphorylation of the mTOR signalling pathway-related proteins induced by Met (

Figure 5A,B). This exploration of molecular mechanisms confirmed that MLCH killed BC cells via the same pathway as Met, but Cs hydrogel notably amplified the effects of Met by acting as an adjuvant. Furthermore, compared with the Met treatment group, tumour growth in the MLCH treatment group was significantly lower than in the Met group (

Figure 5C). Moreover, the staining results of Ki67 as a tumour marker demonstrated similar efficiency patterns (

Figure 5D). Thus, the intravesical administration of MLCH exhibited more potent anti-BC ability, and its effects were mediated by regulation of the AMPK pathways.

2.6. MLCH Exhibits No Detectable Toxic Effects and Remains Localized in the Bladder

To examine whether MLCH induced any toxic effects, tissues from the heart, lungs, liver, and kidneys of mice were taken for pathological examination after 2 weeks of bladder perfusion. Interestingly, no significant differences between the respective tissues were observed in the five groups (

Figure 6A). This indicated that the effects of intravesical administration of MLHC in the bladder were limited to the bladder, and it had no toxic effects on the other organs. Thus, this administration route did not induce any observable side effects.

Moreover, to detect the presence of MLCH in the mouse bladder, the inner wall of the bladder 24 h after Cs administration was examined. As shown in

Figure 6B, compared with the normal bladder tissues, the presence of Cs hydrogels was observed in the MLCH-treated group, indicating that the location of Cs hydrogels was restricted to the bladder wall.

3. Discussion

Cs has received a significant amount of attention in the development of in situ local treatments for tumour therapy, particularly as a potential delivery vehicle in oral and ophthalmic delivery systems [

33,

34,

35,

36]. Hydrogels, cross-linked polymers with high water content, can be used to continuously deliver various therapeutic agents locally [

37,

38,

39,

40]. In addition, Cs structures with a positive charge adhere electrostatically to the mucosal wall of the bladder, which possesses an overall negative charge; thus, it was used to develop a novel formulation of Met [

41,

42]. By combining their respective advantages, a novel MLCH formulation was constructed for controlled topical use.

Cs has been approved for application in the medical field, as its safety profile has been strictly evaluated and is well established [

43,

44,

45]. Moreover, its superior physical features are important for preparing excellent formulations of various drugs. In the present study, no chemical modifications were made to Cs when preparing the lyophilized powder using the freeze-drying method. There were no significant differences between the characteristic peaks between the infrared spectra of MLCH and Met, indicating that the new formulation did not contain any new compounds. Moreover, the UV spectrum of MLCH showed a characteristic absorption peak of Met at 233 nm. Therefore, this formulation does not require any additional safety assessments for future clinical applications. In addition, the freeze-drying method not only effectively removed the volatile acid of Cs, but also directly adjusted the pH to ~5, thereby avoiding the risk of irritation of the mucosa under acidic conditions, and further promoting patient compliance.

The unique barrier structure of the bladder results in only a small amount of accumulation of a drug at the effective site of the bladder when a drug is administered orally, underlying the low efficiency of drugs used for treatment of bladder diseases when administered systemically. Although intravesical administration can reduce the intact dose of drugs required by delivering drugs directly into the bladder, thus reducing the side effects of higher doses [

46], the urine regularly emptied from the bladder significantly reduces the retention time of the drug in this organ, and therefore frequent administration is required. Drug-loaded Cs adheres to the bladder wall and prolongs the action time of drugs. The prepared Cs lyophilized powder showed a loose and porous three- dimensional network structure with high solubility. The drug effectively prepared under these conditions had a certain viscosity. At the same time, the ζ potential of the new Met dosage form was positive, particularly when the Cs concentration was 10 mg/ml. MLCH had the maximum potential value, and this allowed the drug to adhere to the negatively charged bladder membrane. The high concentration of Cs effectively delayed the release of the drug over a 24 h period. Thus, it is speculated that the novel Cs formulation exhibited superior structural features and may prolong the life of the external solution medium entering the bladder wall, leading to a slower release of Met from the carrier matrix into the bladder wall. Furthermore, MLCH with optimized viscosity allowed for extended duration of the action of Met, and thus improved its therapeutic effects. To demonstrate the anti-tumour activity of this novel formulation of Met, comprehensive in vitro and in vivo assays were performed using cultured cells and advanced orthotopic tumour mouse models. The ideal formulation of MLCH, with suitable viscosity and turbidity, was obtained after optimizing the proper ratio of Cs hydrogel to Met. In vivo assays demonstrated the extended retention time and strong anti-tumour activity of this novel formulation. At the same time, Cs alone did not exhibit any significant anti-tumour properties. More importantly, histological analysis showed the excellent non-toxic properties of this novel preparation. Met is a strong 5′-AMPK activator [

47]. The novel formulation showed more potent functional activation of the AMPK/mTOR pathway compared to Met alone.

These findings may have been related to the fact that Cs remained in the bladder for a longer period of time. Cs as a drug carrier prolongs the duration of Met, thereby improving the longevity of the effects of Met. In conclusion, the present study demonstrated a novel formulation of Met with significantly enhanced antitumor effects (

Figure 7)

, which represents a safe and highly efficient potential approach for convenient treatment of BC via intravesical administration.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents

Met (chemical name, 1,1-Dimethylbiguanide hydrochloride) was purchased from Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. Cs (85% degree of deacetylation) was purchased from Haidebei Marine Biological Engineering Co., Ltd. D-Luciferin was purchased from Yanjian Biotechnology Co., Ltd.

4.2. Preparation of Freeze-Dried Cs Powder

A pre-determined weight of regular Cs was dissolved in 1% hydrochloric acid (v/v). The suspension was centrifuged at 30,000 rpm at 4 ˚C for 10 min using an ultracentrifuge to remove the insoluble particles in the Cs solution. The obtained transparent hydrogel was laid flat and frozen at -80 ˚C for pre-freezing, and the freeze-drying temperature and vacuum degree were adjusted to obtain a lyophilized powder of Cs. Finally, the lyophilized powder was mixed with Met-containing physiological saline of different ratios to obtain MLCH of various viscosities.

4.3. Physicochemical Characterization

Turbidity was measured via UV spectrophotometry (Beckman Coulter, Inc.); 1% (v/v) hydrochloric acid solution served as a reference. Using a wavelength range of 200–800 nm, the absorbance of hydrogels with 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 mg/ml Cs was measured. Turbidity was estimated by calculating the transmittance at this wavelength from the absorbance (A) value at 600 nm.

The viscosity of the hydrogels was measured using an Ubbelohde viscometer (Baoshan Qihang Glass Instrument Factory). Briefly, 10 ml polymer hydrogel was injected into the viscometer, maintaining the liquid at a height below atmospheric pressure. When the air pressure in the viscometer was adjusted to maintain atmospheric pressure, the solution dripped due to gravity. The duration of time in sec between the liquid level passing through the upper and lower graduation marks was measured. The measurements were repeated three times, and the difference between the measurements did not exceed 0.1 sec. The outflow time (T) of the test hydrogel was the mean of three measurements. The kinematic viscosity calculation formula used was Viscosity = viscosity capillary inner diameter x viscometer constant x T.

Tyndall effect assays were performed by preparing equivalent volumes of MLCH and Met solution in two test tubes. The light from a laser pointer was illuminated with a white background. The images were taken vertically for recording.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy was performed using a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (Spectrum One B; Perkin Elmer, Inc.), and the scanning range was 4000–500 cm-1.

The UV absorption spectra of MLCH of different concentrations were measured. MLCH was placed in a dialysis bag and dialyzed in the release media of PBS at 37 ˚C. Then, 1 ml hydrogel solution of release media was collected. The amount of drug released was measured using a UV spectrometer (Beckman Coulter, Inc.).

ζ potential analysis was performed using a Zetasizer, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Malvern Nano series, Malvern, UK). Briefly, a diluted suspension of MLCH was prepared in PBS to measure the ζ potential. All analyses were performed in triplicate.

4.4. Cell Viability Assay

The murine BC cell line, MB49, was kindly provided by Dr P Guo (Institute of Urology, Xi’an Jiaotong University). MB49 cells were cultured in DMEM (Hyclone; Cytiva) supplemented with 10% FBS (Hyclone; Cytiva) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were cultured at 37 ˚C with 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator and were frequently assessed for mycoplasma contamination.

Cell viability was assessed using MTT assay using a microplate reader (SYNERGY HTX; BioTek Instruments, Inc.). Briefly, cells were seeded at a density of 8x103 cells/well in 96-well culture plates and incubated in medium supplemented with 10% FBS. After 12 h, cells were treated with different concentrations of MLCH or with Met alone for 2 h. Then, cells were cultured for a further 48 h in the culture medium. The tetrazolium salt of MTT (50 μl; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) was dissolved in Hank’s balanced salt solution to a concentration of 2 mg/ml, added to each well, and incubated for 5 h. Subsequently, the medium was aspirated from each well, and 150 μl DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) was added to dissolve the formazan crystals. The absorbance was measured using a microplate reader at 490 nm against the reference absorbance at 630 nm. Data were statistically analysed using SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS, Inc.).

4.5. Clonogenic Assay

MB49 BC cells (8x103 cells/well) were plated in a 24-well plate and incubated for 24 h at 37 ˚C. Subsequently, cells were treated with Met alone or with different concentrations of MLCH for 2 h in media supplemented with 10% FBS. Then, the drug-containing medium was replaced with DMEM. The cells were then treated twice with the different preparations for 2 h each time, fixed with 10% formaldehyde after 7 days of culture, and stained with 0.1% crystal violet at room temperature for 4 hours. Absorbance was measured using a microplate reader at a wavelength of 550 nm.

4.6. Orthotopic Implantation and Intravesical Treatment

Female C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Hunan SJA Laboratory Animal, Co., Ltd. Animals were housed in a specific pathogen-free animal facility.

MB49 cells (transfected with luciferase) in the exponential growth phase were harvested, and the cell density in the collection tubes was counted using a cell counter. A total of 1.2x10

5 MB49 cells in 0.1 ml PBS were injected into the bladder walls of mice using 1 ml syringes following catheter scratching to establish the orthotopic BC mouse model, as described previously [

48]. The mice were divided into five groups: i) normal, normal female C57BL/6 mice administered 50 μl saline intravesically, but not injected with tumour cells; and female C57BL/6 mice with orthotopic BC treated with ii) 50 μl saline (Ctrl); iii) Cs hydrogel (10 mg/ml; Cs); iv) Met (80 mM; Met); or v) 10 mg/ml Cs hydrogel loaded with 80 mM Met (MLCH). Each group consisted of six female C57BL/6 mice. All treatments began on the second day after the successful establishment of the orthotopic model, were administered once a week, and lasted for 2 weeks. Mice were anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg) and then sacrificed via cervical dislocation. Tumour burden was assessed using a Xenogen In Vivo Imaging system (PerkinElmer, Inc.).

4.7. Histological Analysis

At the end of the study, the animals were sacrificed, and the bladder, heart, lung, liver, and kidneys were removed. Portions of organ tissues were used for protein extraction or immediately immersed in 4% neutral buffered formalin for histological slide preparations. The samples used for histological analysis were subsequently processed using conventional histological techniques. Haematoxylin and eosin, as well as Ki67 staining of 7 μm tissue sections, were performed. The slides were observed using a light microscope (DFC450C; Leica Microsystems GmbH). Pathological evaluation of tissues was performed to confirm the presence of tumours, as well as other pathological features.

4.8. Western Blotting

Total tissue protein was extracted using a grinder (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.), and ~10 μl protein tissue fluid containing 30 μg total protein was resolved using SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes, after which the membranes were cut according to the corresponding molecular weight of the protein. Membranes were incubated with the primary antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) and incubated overnight at 4 ˚C. The following day, membranes were washed with PBS containing 1% Tween-20 and blotted with the secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature, and then washed again three times. Pierce Super Signal chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used to visualize the signals, and the blot was imaged immediately using a ChemiDoc system (Tanon 4600; Tanon Science and Technology Co., Ltd.). Densitometry analysis was performed using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health).

4.9. Statistical Analysis

Data from the in vitro experiments are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. In vivo experimental results are expressed as the mean ± the standard error of the mean. Differences between groups were compared using a Student’s t-test (two groups) or a one-way ANOVA with a post hoc least significant difference test (more than two groups). Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 6.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc.) or Origin version 8.0 (OriginLab Corporation). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Author Contributions

Xingjian Zhang, Xin Hu and yijun Xie performed the experiments. Lejing Xie, Xiangyi Chen, Mei Peng, Duo Li, and Jun Deng performed the statistical analysis. Di Xiao and Xiaoping Yang designed the study, edited the manuscript, and participated in interpretation of the results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82172653); Institutional Open Fund (KF2022001, KF2021017), Key Project of Developmental Biology and Breeding from Hunan Province (2022XKQ0205); Natural Science Foundation of Changsha (kq2202387); Graduate Scientific Research Innovation Project of Hunan Province, China (QL20220115).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper, or from the corresponding authors upon request.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge other members of the Key Laboratory of Study and Discovery of Small Targeted Molecules of Hunan Province for thoughtful discussion of this manuscript. The authors thank Mr. Zhou Wang at College of Biology, Hunan University for his assistance with IR analysis and helpful discussions. The authors also thank Medical Doctor Ms. Tianyu Wu at Department of Pathology of the Center Hospital of Zhu Zhou City for her assistance with tissue section staining and helpful discussions.

Ethics approval and consent to participate: The experimental protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Hunan Normal University (Protocol 2019030).

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

References

- Xiao D: Hu X, Peng M, Deng J, Zhou S, Xu S, Wu J, Yang X. Inhibitory role of proguanil on the growth of bladder cancer via enhancing EGFR degradation and inhibiting its downstream signaling pathway to induce autophagy. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu C, Wang S, Lai WF, Zhang D. The Progress of Chitosan-Based Nanoparticles for Intravesical Bladder Cancer Treatment. Pharmaceutics. 2023, 15.

- Xiao D, Xu S, Zhou X, et al. Synergistic augmentation of osimertinib-induced autophagic death by proguanil or rapamycin in bladder cancer. MedComm. 2023, 4, e236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foretz M, Guigas B, Bertrand L, Pollak M, Viollet B. Metformin: from mechanisms of action to therapies. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 953–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitson SJ, Maskell Z, Sivalingam VN, et al. PRE-surgical Metformin In Uterine Malignancy (PREMIUM): a Multi-Center, Randomized Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase III Trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 2424–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakiridis T, Pond GR, Wright J, et al. Metformin in Combination With Chemoradiotherapy in Locally Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: The OCOG-ALMERA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2021, 7, 1333–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li L, Jiang L, Wang Y, et al. Combination of Metformin and Gefitinib as First-Line Therapy for Nondiabetic Advanced NSCLC Patients with EGFR Mutations: A Randomized, Double-Blind Phase II Trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 6967–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng J, Peng M, Zhou S, Xiao D, Hu X, Xu S, Wu J, Yang X. Metformin targets Clusterin to control lipogenesis and inhibit the growth of bladder cancer cells through SREBP-1c/FASN axis. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021, 6, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu S, Xu L, Kang ET, Mahendran R, Chiong E, Neoh KG. Co-delivery of peptide-modified cisplatin and doxorubicin via mucoadhesive nanocapsules for potential synergistic intravesical chemotherapy of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2016, 84, 103–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhaveri J, Raichura Z, Khan T, Momin M, Omri A. Chitosan Nanoparticles-Insight into Properties, Functionalization and Applications in Drug Delivery and Theranostics. Molecules. 2021, 26.

- Garg U, Chauhan S, Nagaich U, Jain N. Current Advances in Chitosan Nanoparticles Based Drug Delivery and Targeting. Adv Pharm Bull. 2019, 9, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Hafez SM, Hathout RM, Sammour OA. Towards better modeling of chitosan nanoparticles production: screening different factors and comparing two experimental designs. Int J Biol Macromol. 2014, 64, 334–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narmani A, Jafari SM. Chitosan-based nanodelivery systems for cancer therapy: Recent advances. Carbohydr Polym. 2021, 272, 118464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li D, Fu D, Kang H, Rong G, Jin Z, Wang X, Zhao K. Advances and Potential Applications of Chitosan Nanoparticles as a Delivery Carrier for the Mucosal Immunity of Vaccine. Curr Drug Deliv. 2017, 14, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu Y, Huo M, Fu Y, et al. N-Deoxycholic acid-N,O-hydroxyethyl Chitosan with a Sulfhydryl Modification To Enhance the Oral Absorptive Efficiency of Paclitaxel. Mol Pharm. 2017, 14, 4539–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed TA, Aljaeid BM. Preparation, characterization, and potential application of chitosan, chitosan derivatives, and chitosan metal nanoparticles in pharmaceutical drug delivery. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2016, 10, 483–507. [Google Scholar]

- Yavuz B, Morgan JL, Herrera C, Harrington K, Perez-Ramirez B, LiWang PJ, Kaplan DL. Sustained release silk fibroin discs: Antibody and protein delivery for HIV prevention. J Control Release. 2019, 301, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perioli L, Ambrogi V, Venezia L, Pagano C, Ricci M, Rossi C. Chitosan and a modified chitosan as agents to improve performances of mucoadhesive vaginal gels. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2008, 66, 141–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perinelli DR, Campana R, Skouras A, Bonacucina G, Cespi M, Mastrotto F, Baffone W, Casettari L. Chitosan Loaded into a Hydrogel Delivery System as a Strategy to Treat Vaginal Co-Infection. Pharmaceutics. 2018, 10.

- Frank LA, Sandri G, D’Autilia F, Contri RV, Bonferoni MC, Caramella C, Frank AG, Pohlmann AR, Guterres SS. Chitosan gel containing polymeric nanocapsules: a new formulation for vaginal drug delivery. Int J Nanomedicine. 2014, 9, 3151–61. [Google Scholar]

- Vikas, Viswanadh MK, Mehata AK, Sharma V, Priya V, Varshney N, Mahto SK, Muthu MS. Bioadhesive chitosan nanoparticles: Dual targeting and pharmacokinetic aspects for advanced lung cancer treatment. Carbohydr Polym. 2021, 274, 118617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo H, Li F, Qiu H, Liu J, Qin S, Hou Y, Wang C. Preparation and Characterization of Chitosan Nanoparticles for Chemotherapy of Melanoma Through Enhancing Tumor Penetration. Front Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng M, Huang Y, Tao T, Peng CY, Su Q, Xu W, Darko KO, Tao X, Yang X. Metformin and gefitinib cooperate to inhibit bladder cancer growth via both AMPK and EGFR pathways joining at Akt and Erk. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 28611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su Q, Tao T, Tang L, et al. Down-regulation of PKM2 enhances anticancer efficiency of THP on bladder cancer. J Cell Mol Med. 2018, 22, 2774–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John BA, Said N. Insights from animal models of bladder cancer: recent advances, challenges, and opportunities. Oncotarget. 2017, 8, 57766–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koga T, Kamiwatari S, Higashi NJLtAJoS, Colloids. Preparation and Self-Assembly Behavior of β-Sheet Peptide-Inserted Amphiphilic Block Copolymer as a Useful Polymeric Surfactant. Langmuir. 2013, 29, 15477–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaz AF, Sobral de Carvalho SM, Barbosa RC, Silva SML, Sabino Gutierrez MA, de Lima AGB, Fook MVL. Ionically Crosslinked Chitosan Membranes Used as Drug Carriers for Cancer Therapy Application. Materials. 2018, 11, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Yue GG, Gao S, Lee JK, et al. A Natural Flavone Tricin from Grains Can Alleviate Tumor Growth and Lung Metastasis in Colorectal Tumor Mice. Molecules. 2020, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi K, Miyake K, Han Q, et al. Targeting altered cancer methionine metabolism with recombinant methioninase (rMETase) overcomes partial gemcitabine-resistance and regresses a patient-derived orthotopic xenograft (PDOX) nude mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Cell Cycle. 2018, 17, 868–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemdani K, Seguin J, Lesieur C, et al. Mucoadhesive thermosensitive hydrogel for the intra-tumoral delivery of immunomodulatory agents, in vivo evidence of adhesion by means of non-invasive imaging techniques. Int J Pharm. 2019, 567, 118421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Huang L, Shi X, et al. Metformin protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury and cell pyroptosis via AMPK/NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. Aging-Us. 2020, 12, 24270–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn HK, Lee YH, Koo KC. Current Status and Application of Metformin for Prostate Cancer: A Comprehensive Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21.

- Ahsan SM, Thomas M, Reddy KK, Sooraparaju SG, Asthana A, Bhatnagar I. Chitosan as biomaterial in drug delivery and tissue engineering. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2018, 110, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong X, Xu W, Zhang C, Kong WJE, Medicine T. Chitosan temperature-sensitive gel loaded with drug microspheres has excellent effectiveness, biocompatibility and safety as an ophthalmic drug delivery system. Exp Ther Med. 2018, 15, 1442–8. [Google Scholar]

- Schaffhausen N, Tijsma E, Hissong B. Injectable chitosan-based hydrogels for drug delivery after ear-nose-throat surgery. Journal of Controlled Release. 2008, 132, E47–E8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu Y, Huo M, Fu Y, et al. N-Deoxycholic acid-N,O-hydroxyethyl Chitosan with a Sulfhydryl Modification To Enhance the Oral Absorptive Efficiency of Paclitaxel. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2017, 14, 4539–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattarai N, Gunn J, Zhang M. Chitosan-based hydrogels for controlled, localized drug delivery. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2010, 62, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Censi R, Martino PD, Vermonden T, Society WEHJJoCROJotCR. Hydrogels for protein delivery in tissue engineering. Journal of Controlled Release. 2012, 161, 680–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu Z, Chen J, Zhou S, et al. Mouse IP-10 Gene Delivered by Folate-modified Chitosan Nanoparticles and Dendritic/tumor Cells Fusion Vaccine Effectively Inhibit the Growth of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Mice. Theranostics. 2017, 7, 1942–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Liu JG, Chen WM, Yu AXJE, Medicine T. Efficacy of thermosensitive chitosan/βglycerophosphate hydrogel loaded with βcyclodextrincurcumin for the treatment of cutaneous wound infection in rats. Exp Ther Med. 2018, 15, 1304–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Xu M, Cheng X, Kong M, Chen XJCP. Positive/negative surface charge of chitosan based nanogels and its potential influence on oral insulin delivery. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2015, 136, 867–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ali A, Ahmed S. A review on chitosan and its nanocomposites in drug delivery. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2018, 109, 273–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran HBT, Turley JL, Andersson M, Lavelle EC. Immunomodulatory properties of chitosan polymers. Biomaterials. 2018, 184, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kean T, Thanou M. Biodegradation, biodistribution and toxicity of chitosan. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2010, 62, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hathout RM, Kassem DH. Positively Charged Electroceutical Spun Chitosan Nanofibers Can Protect Health Care Providers From COVID-19 Infection: An Opinion. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 885. [Google Scholar]

- GuhaSarkar S, Banerjee R. Intravesical drug delivery: Challenges, current status, opportunities and novel strategies. Journal of Controlled Release. 2010, 148, 147–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou G, Myers R, Li Y, et al. Role of AMP-activated protein kinase in mechanism of metformin action. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2001, 108, 1167–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang X, Kessler E, Su L-J, et al. Diphtheria Toxin-Epidermal Growth Factor Fusion Protein DAB(389)EGF for the Treatment of Bladder Cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2013, 19, 148–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Physical characteristics of Cs hydrogels. (A) Concentration-dependent transmittance changes of the Cs hydrochloride solution at a wavelength of 600 nm. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of three repetitions. (B) After placing it in a vacuum at low temperature, the clear solution (left) of regular Cs powder dissolved in 1% hydrochloric acid (v/v) became a uniform lyophilized powder of Cs (right). (C) Lyophilized Cs powder could be dissolved in Met physiological saline to form even MLCH (right), whereas regular Cs powder could not (left). (D) Micro-structural differences between the regular and lyophilized powder. The images were taken using an inverted microscope. (E) Results of the Tyndall effect assay on MLCH and Met. (F) Infrared spectra of MLCH, Met, and Cs hydrogels. (G) NMR hydrogen spectra of MLCH, Met and Cs hydrogels. (H) The prepared Cs lyophilized powder showed a loose and porous three dimen sional network structure, so it has a high metformin loading capacity. MLCH, metformin-loaded Cs hydrogel; Met, metformin.

Figure 1.

Physical characteristics of Cs hydrogels. (A) Concentration-dependent transmittance changes of the Cs hydrochloride solution at a wavelength of 600 nm. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of three repetitions. (B) After placing it in a vacuum at low temperature, the clear solution (left) of regular Cs powder dissolved in 1% hydrochloric acid (v/v) became a uniform lyophilized powder of Cs (right). (C) Lyophilized Cs powder could be dissolved in Met physiological saline to form even MLCH (right), whereas regular Cs powder could not (left). (D) Micro-structural differences between the regular and lyophilized powder. The images were taken using an inverted microscope. (E) Results of the Tyndall effect assay on MLCH and Met. (F) Infrared spectra of MLCH, Met, and Cs hydrogels. (G) NMR hydrogen spectra of MLCH, Met and Cs hydrogels. (H) The prepared Cs lyophilized powder showed a loose and porous three dimen sional network structure, so it has a high metformin loading capacity. MLCH, metformin-loaded Cs hydrogel; Met, metformin.

Figure 2.

Characterization of MLCH. (A) The UV spectra of MLCH showed the characteristic absorption peak of Met at 233 nm. (B) After freeze-drying, MLCH had a pH of ~5, which satisfied the requirements for bladder perfusion. (C) MLCH had a positive ζ potential, which is beneficial for adhesion to the bladder mucosa. MLCH, metformin-loaded Cs hydrogel.

Figure 2.

Characterization of MLCH. (A) The UV spectra of MLCH showed the characteristic absorption peak of Met at 233 nm. (B) After freeze-drying, MLCH had a pH of ~5, which satisfied the requirements for bladder perfusion. (C) MLCH had a positive ζ potential, which is beneficial for adhesion to the bladder mucosa. MLCH, metformin-loaded Cs hydrogel.

Figure 3.

Different concentrations of Cs hydrogels and Met synergistically inhibited bladder cancer growth in vitro. (A) MB49 cells were treated with Cs hydrogel for 2 h. Then, the cells were cultured for 48 h after removal of the Cs hydrogels. Images were taken using an inverted microscope. (B and C) MB49 cells were treated with Cs or MLCH for 2 h. Then, the cells were cultured for 48 h after removal of the Cs or MLCH, the viability of MB49 cells were assessed by MTT assay. (D and E) MB49 cells were treated with Cs or MLCH for 2 h (twice in 1 week) and then cultured with complete medium, the viability of MB49 cells were assessed by Colony formation assays. (F and G) Quantification of the colony formation assays. The wells were scanned at a wavelength of 550 nm. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of five independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. MLCH, metformin-loaded chitosan hydrogel; Ctrl, control; Cs, chitosan alone; Met, metformin alone.

Figure 3.

Different concentrations of Cs hydrogels and Met synergistically inhibited bladder cancer growth in vitro. (A) MB49 cells were treated with Cs hydrogel for 2 h. Then, the cells were cultured for 48 h after removal of the Cs hydrogels. Images were taken using an inverted microscope. (B and C) MB49 cells were treated with Cs or MLCH for 2 h. Then, the cells were cultured for 48 h after removal of the Cs or MLCH, the viability of MB49 cells were assessed by MTT assay. (D and E) MB49 cells were treated with Cs or MLCH for 2 h (twice in 1 week) and then cultured with complete medium, the viability of MB49 cells were assessed by Colony formation assays. (F and G) Quantification of the colony formation assays. The wells were scanned at a wavelength of 550 nm. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of five independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. MLCH, metformin-loaded chitosan hydrogel; Ctrl, control; Cs, chitosan alone; Met, metformin alone.

Figure 4.

MLCH inhibits BC growth in vivo when administered intravesically. (A) Bioluminescent images of the mouse orthotopic implantation model following the different treatments. (B) Total weight of mice during the entire procedure. (C) Images of the explanted bladder tissues. (D) Weights of the mouse bladders, including those of mice that died before the end of experiment. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of five independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. BC, bladder cancer; MLCH, metformin-loaded chitosan hydrogel; Ctrl, control; Cs, chitosan alone; Met, metformin alone.

Figure 4.

MLCH inhibits BC growth in vivo when administered intravesically. (A) Bioluminescent images of the mouse orthotopic implantation model following the different treatments. (B) Total weight of mice during the entire procedure. (C) Images of the explanted bladder tissues. (D) Weights of the mouse bladders, including those of mice that died before the end of experiment. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of five independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. BC, bladder cancer; MLCH, metformin-loaded chitosan hydrogel; Ctrl, control; Cs, chitosan alone; Met, metformin alone.

Figure 5.

Inhibitory effect of MLCH on AMPK signalling pathways in bladder cancer. (A) Western blot analysis of p-AMPKα, p-mTOR, p-P70s6k, and p-4Ebp1 protein expression in bladder tissues from the mice in the five different groups. (B) Relative levels of p-AMPKα, mTOR, P70s6k, and 4Ebp1 are shown as the mean ± the standard error of the mean. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001. (C and D) Histological sections of the bladder tissues were subjected to haematoxylin and eosin staining or were used for immunohistochemistry analysis of Ki67 expression to confirm the presence or absence of tumours. MLCH, metformin-loaded chitosan hydrogel; Ctrl, control; Cs, chitosan alone; Met, metformin alone; p-, phosphor; P70s6k, ribosomal protein S6 kinase; 4Ebp1, eukaryotic translation initiation factor binding protein 1.

Figure 5.

Inhibitory effect of MLCH on AMPK signalling pathways in bladder cancer. (A) Western blot analysis of p-AMPKα, p-mTOR, p-P70s6k, and p-4Ebp1 protein expression in bladder tissues from the mice in the five different groups. (B) Relative levels of p-AMPKα, mTOR, P70s6k, and 4Ebp1 are shown as the mean ± the standard error of the mean. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001. (C and D) Histological sections of the bladder tissues were subjected to haematoxylin and eosin staining or were used for immunohistochemistry analysis of Ki67 expression to confirm the presence or absence of tumours. MLCH, metformin-loaded chitosan hydrogel; Ctrl, control; Cs, chitosan alone; Met, metformin alone; p-, phosphor; P70s6k, ribosomal protein S6 kinase; 4Ebp1, eukaryotic translation initiation factor binding protein 1.

Figure 6.

Pathological examination of the vital organs. (A) Pathological examination of the vital organs in the five groups of mice. Haematoxylin and eosin staining were used for pathological examination of tissue sections of the heart, lung, liver, and kidneys. (B) Observation of the inner wall of the bladder showed Cs was retained for ≥24 h. The bladder tissue was assessed using haematoxylin and eosin staining following the administration of MLCH for 24 h to observe the retention of Cs. MLCH, metformin-loaded chitosan hydrogel; Ctrl, control; Cs, chitosan alone; Met, metformin alone.

Figure 6.

Pathological examination of the vital organs. (A) Pathological examination of the vital organs in the five groups of mice. Haematoxylin and eosin staining were used for pathological examination of tissue sections of the heart, lung, liver, and kidneys. (B) Observation of the inner wall of the bladder showed Cs was retained for ≥24 h. The bladder tissue was assessed using haematoxylin and eosin staining following the administration of MLCH for 24 h to observe the retention of Cs. MLCH, metformin-loaded chitosan hydrogel; Ctrl, control; Cs, chitosan alone; Met, metformin alone.

Figure 7.

Scheme of MLCH delivery system and mechanism of action. (A) MLCH exerts a beneficial therapeutic effect in an orthotopic mouse model of bladder cancer via extending metformin retention time. (B) MLCH activates AMPK and down-regulates the mTOR signal pathway, thereby inhibiting p70S6K and 4EBP1 phosphorylation to block the tumor cell growth.

Figure 7.

Scheme of MLCH delivery system and mechanism of action. (A) MLCH exerts a beneficial therapeutic effect in an orthotopic mouse model of bladder cancer via extending metformin retention time. (B) MLCH activates AMPK and down-regulates the mTOR signal pathway, thereby inhibiting p70S6K and 4EBP1 phosphorylation to block the tumor cell growth.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).