Submitted:

11 September 2023

Posted:

13 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study design

Participants

Data collection

Ethical consideration

Data analysis

Rigour

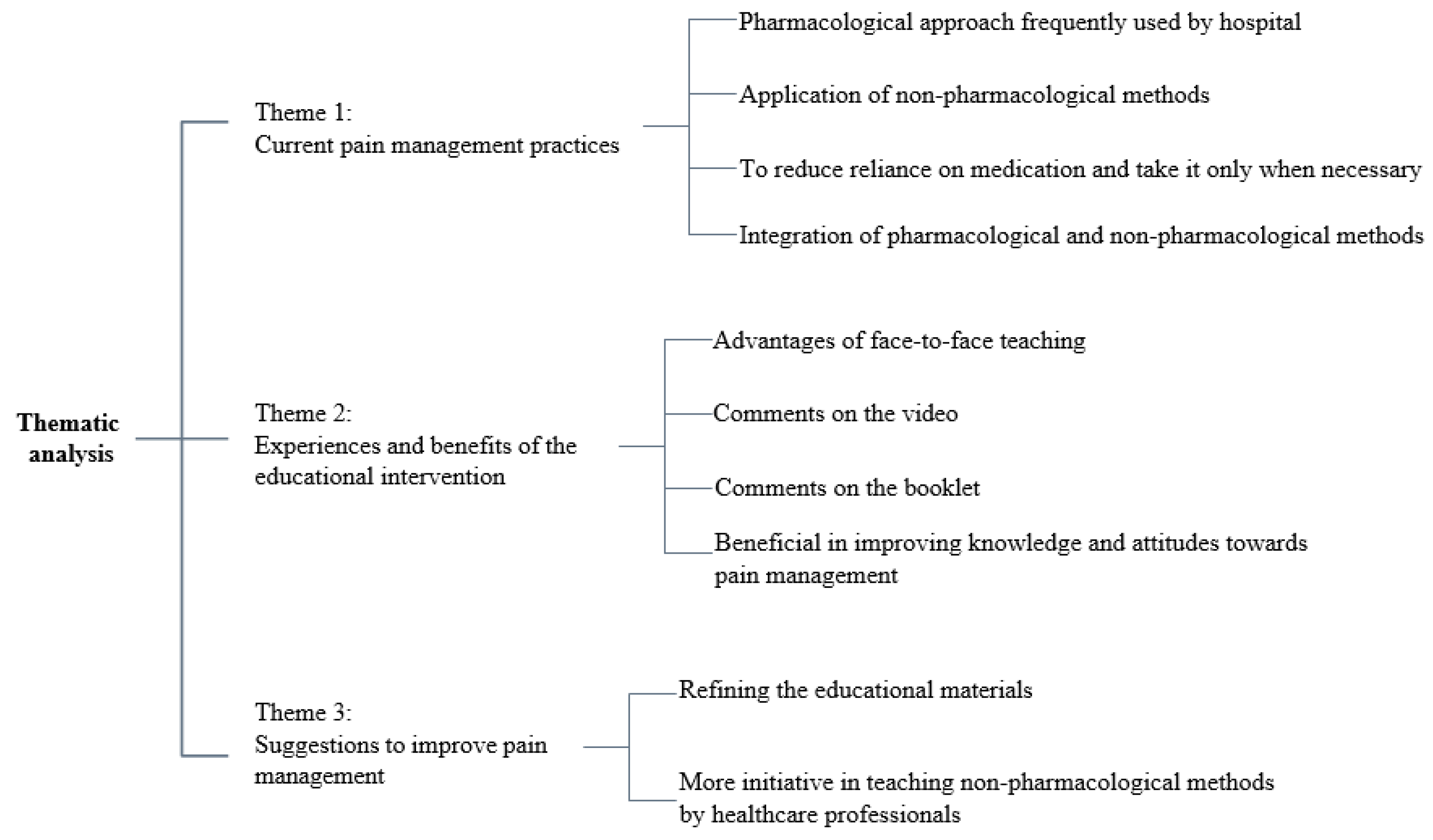

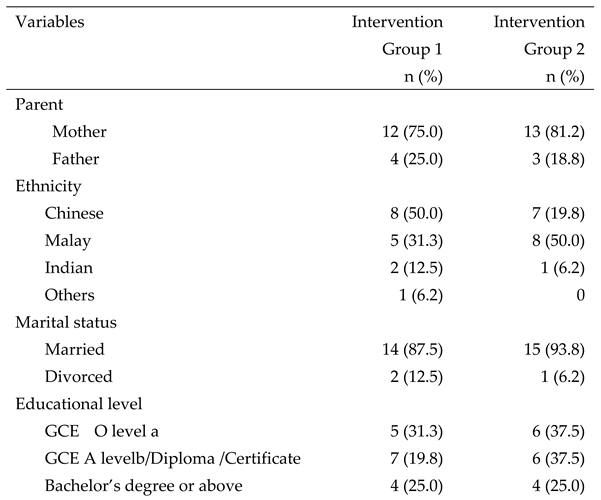

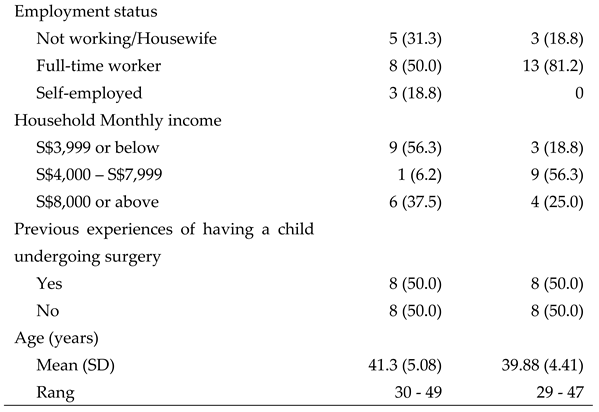

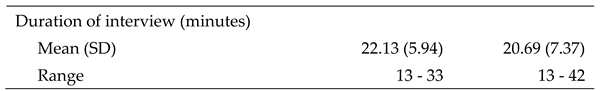

3. Results

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations of this study

Implications for Nursing Practice and Recommendations for Future Studies

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Links, A.R. , Callonb, W., Wasserman, C., Jonathan Walsha, J., Tunkela, D.E., Beachc, M.C., & Boss, E.F. Parental role in decision-making for pediatric surgery: Perceptions of involvement in consultations for tonsillectomy. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 944–951. [Google Scholar]

- Makhlouf, M.M.; Garibay, E.R.; Jenkins, B.N.; Kain, Z.N.; A Fortier, M. Postoperative pain: factors and tools to improve pain management in children. Pain Manag. 2019, 9, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, W.; Huang, H.; Jiang, W.; Zhou, Y.; Gu, Y.; Xu, H.; Yao, W.; Zhang, F. Parental involvement in postoperative pain management among children in a urology ward: A best practice implementation project. First published: 25 December 2022, 25 December. [CrossRef]

- Dagg, W.; Forgeron, P.; Macartney, G.; Chartrand, J. Parents’ management of adolescent patients’ postoperative pain after discharge: A qualitative study. Can. J. Pain 2020, 4, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomaa, A.-K.; Korhonen, A.; Pölkki, T. Factors Influencing Parental Participation in Neonatal Pain Alleviation. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2016, 31, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabriel, M.G.; Wakefield, C.E.; Vetsch, J.; Karpelowsky, J.S.; Darlington, A.-S.E.; Grant, D.M.; Signorelli, C. The Psychosocial Experiences and Needs of Children Undergoing Surgery and Their Parents: A Systematic Review. J. Pediatr. Heal. Care 2017, 32, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simons, J.; Carter, B.; Craske, J. Developing a Framework to Support the Delivery of Effective Pain Management for Children: An Exploratory Qualitative Study. Pain Res. Manag. 2020, 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.H.; Mackey, S.; Liam, J.L.W.; He, H. An exploration of Singaporean parental experiences in managing school-aged children’s postoperative pain: a descriptive qualitative approach. J. Clin. Nurs. 2011, 21, 860–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chng, H. Y. , He, H. G., Chan, S. W. C., Liam, J. L. W., Zhu, L., & Cheng, K. K. F. (2015). Parents’ knowledge, attitudes, use of pain relief methods and satisfaction related to their children's postoperative pain management: a descriptive correlational study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24(11-12), 1630-1642.

- Huth, M.M.; Broome, M.E.; Mussatto, K.A.; Morgan, S.W. A study of the effectiveness of a pain management education booklet for parents of children having cardiac surgery. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2003, 4, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M. , Malar Kodi, S., & Deol, R. (2020). Effect of preoperative educational schedule on anxiety and coping mechanism among children and their parents: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Pediatric Surgical Nursing, 9(4), 127-135.

- Chartrand, J.; Tourigny, J.; MacCormick, J. The effect of an educational pre-operative DVD on parents’ and children's outcomes after a same-day surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 73, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins Esteves, I. , Silva Coelho, M., Neves, H., Pestana-Santos, M., & Santos, M.R. (2022). Effectiveness of family-centred educational interventions in the anxiety, pain and behaviours of children/adolescents and their parents’ anxiety in the perioperative period: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Perioperative Nursing, 35(1), Article 1.

- He, H.; Zhu, L.; Chan, W.S.; Xiao, C.; Klainin-Yobas, P.; Wang, W.; Cheng, K.F.K.; Luo, N. A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of an educational intervention on outcomes of parents and their children undergoing inpatient elective surgery: study protocol. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 71, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Chan, W.-C.S.; Liam, J.L.W.; Xiao, C.; Lim, E.C.C.; Luo, N.; Cheng, K.F.K.; He, H. Effects of postoperative pain management educational interventions on the outcomes of parents and their children who underwent an inpatient elective surgery: A randomized controlled trial. J. Adv. Nurs. 2018, 74, 1517–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pölkki, T.; Vehviläinen-Julkunen, K.; Pietilä, A.-M.; Mnsc, T.P. Nonpharmacological methods in relieving children’s postoperative pain: a survey on hospital nurses in Finland. J. Adv. Nurs. 2001, 34, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H., & Bondas, T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 15(3), 398-405. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houghton, C.; Casey, D.; Shaw, D.; Murphy, K. Rigour in qualitative case-study research. Nurse Res. 2013, 20, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noble, H. , & Smith, J. (2015). Issues of validity and reliability in qualitative research. Evidence-Based Nursing, 18(2), 34-35. [CrossRef]

- Oremule, B.; Johnson, M.; Sanderson, L.; Lutz, J.; Dodd, J.; Hans, P. Oral morphine for pain management in paediatric patients after tonsillectomy and adenotonsillectomy. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2015, 79, 2166–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergomi, P.; Scudeller, L.; Pintaldi, S.; Molin, A.D. Efficacy of Non-pharmacological Methods of Pain Management in Children Undergoing Venipuncture in a Pediatric Outpatient Clinic: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Audiovisual Distraction and External Cold and Vibration. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2018, 42, e66–e72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukola, I.M.; Paula, D. The Effectiveness of Distraction as Procedural Pain Management Technique in Pediatric Oncology Patients: A Meta-analysis and Systematic Review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2017, 54, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S. W. , Rosenkilde, C., Lauridsen, J., & Hasfeldt, D. (2020). Effects of Nonpharmacologic Distraction Methods on Children's Postoperative Pain—A Nonmatched Case-Control Study. Journal of Perianesthesia Nursing, 35(2), 147-154.

- Short, S.; Pace, G.; Birnbaum, C. Nonpharmacologic Techniques to Assist in Pediatric Pain Management. Clin. Pediatr. Emerg. Med. 2017, 18, 256–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.; Forgeron, P.; Polomeno, V.; Gharaibeh, H.; Harrison, D. Pain Management Practice and Guidelines in Jordanian Pediatric Intensive Care Units. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2018, 19, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valizadeh, F.; Ahmadi, F.; Zarea, K. Neglect of Postoperative Pain Management in Children: A Qualitative Study Based on the Experiences of Parents. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2016, 31, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Biswas, H.B.; Hossain, M.S.; Kim, H.S.; Azim, A.; Nath, P.; A Ali, M. Knowledge and Practice of Nurses on Pediatric Pain Management in Bangladesh. Mymensingh Medical Journal 2020, 29, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chung, W. W. , Agbayani, C. J. G., Martinez, A., Le, V., Cortes, H., Har, K.,... & Fortier, M. A. (2018). Improving Children's cancer pain management in the home setting: Development and formative evaluation of a web-based program for parents. Computers in Biology and Medicine, 101, 146-152.

- He, H.-G.; Vehviläinen-Julkunen, K.; Pietilä, A.-M.; Pölkki, T. Increasing Nurses' Knowledge and Behavior Changes in Nonpharmacological Pain Management for Children in China. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2008, 23, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, H.G. , Vehviläinen-Julkunen, K., Pölkki, T., & Pietilä, A.M. (2010). Chinese parents' perception of support received and recommendations regarding children's postoperative pain management. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 16, 254-261.

- Chou, R.; Gordon, D.B.; de Leon-Casasola, O.A.; Rosenberg, J.M.; Bickler, S.; Brennan, T.; Carter, T.; Cassidy, C.L.; Chittenden, E.H.; Degenhardt, E.; et al. Management of Postoperative Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists' Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. J. Pain 2016, 17, 131–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortier, M. A. , Yang, S., Phan, M. T., Tomaszewski, D. M., Jenkins, B. N., & Kain, Z. N. (2020). Children's cancer pain in a world of the opioid epidemic: Challenges and opportunities. Pediatric Blood and Cancer, 67(4), e28124.

- Gogovor, A.; Visca, R.; Auger, C.; Bouvrette-Leblanc, L.; Symeonidis, I.; Poissant, L.; Ware, M.A.; Shir, Y.; Viens, N.; Ahmed, S. Informing the development of an Internet-based chronic pain self-management program. Int. J. Med Informatics 2017, 97, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwa, Z.Y. (2020). Developing and testing the feasibility and preliminary effects of an intelligent customer-driven solution for paediatric surgery care on the improvement of outcomes of parents and their children undergoing circumcision (ICory- Circumcision): A pilot randomised controlled trial. Honour’s Thesis. Singapore: National University of Singapore.

- Fortier, M. A. , Chung, W. W., Martinez, A., Gago-Masague, S., & Sender, L. Pain buddy: A novel use of m-health in the management of children's cancer pain. Computers in Biology and Medicine, 2016, 76, 202–214. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.G. (2018). Preliminary effects of using mobile games to reduce perioperative anxiety and postoperative pain in children undergoing elective surgery: A pilot randomised controlled trial. Honour’s Thesis. Singapore: National University of Singapore.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).