Submitted:

11 September 2023

Posted:

13 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Innovative work behavior

2.2.2. Creativity

2.2.3. Prosocial motivation

2.2.4. Prosocial impact

2.2.5. Needs satisfaction

2.2.6. Benevolence satisfaction

2.2.7. Control variables.

2.3. Data analysis

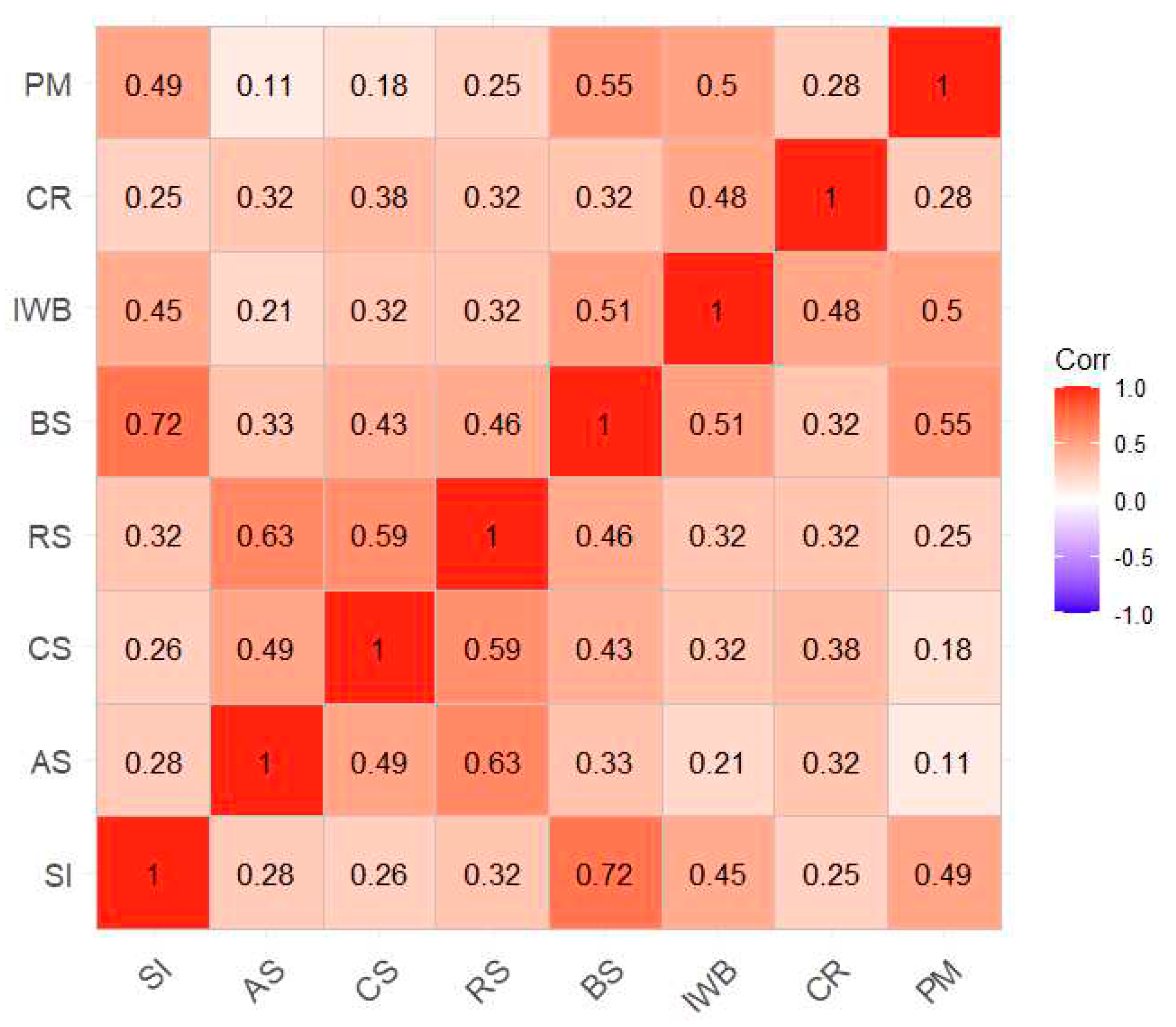

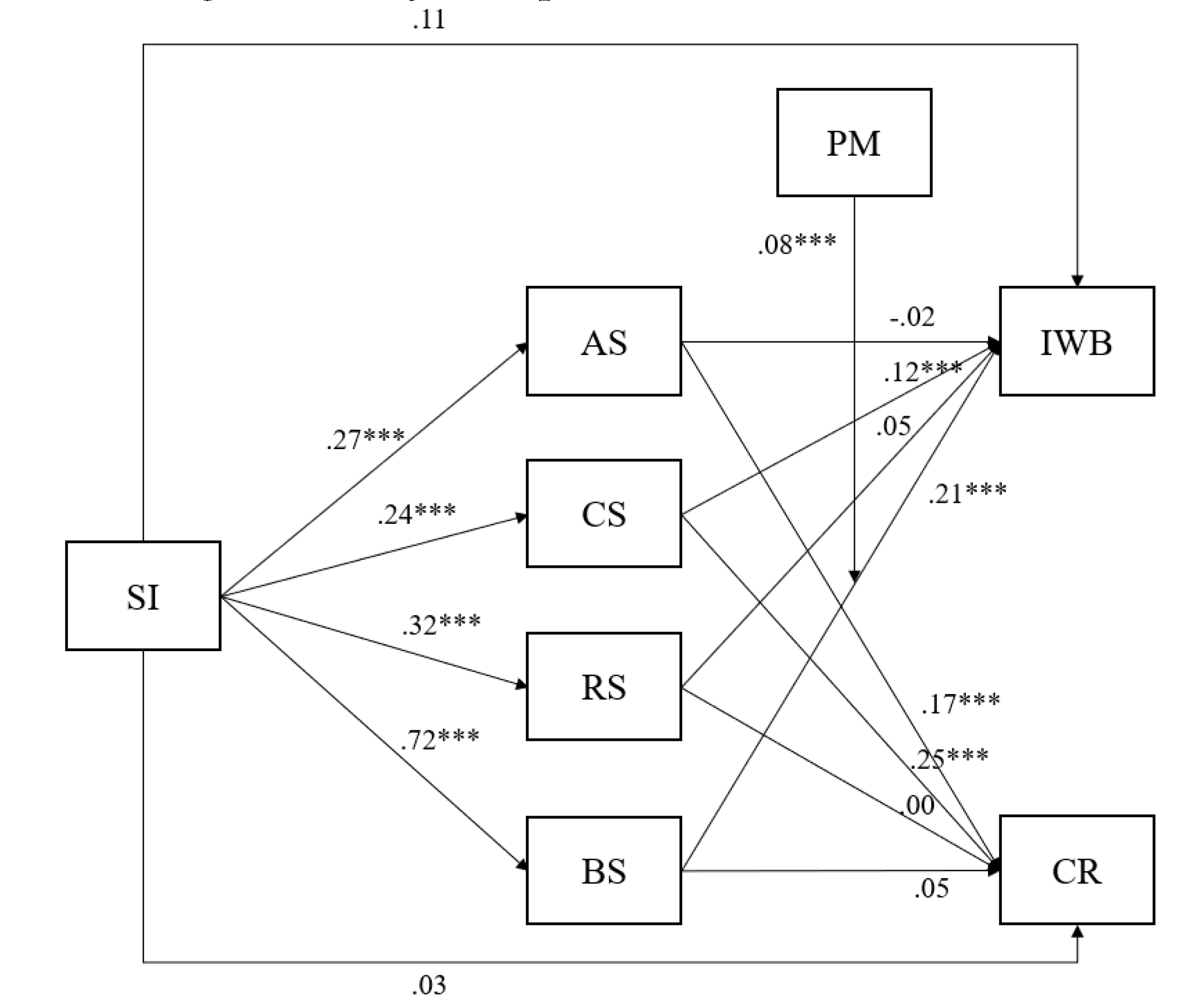

3. Results

3.1. Effect of social impact on need satisfaction

3.2. Effect of need satisfaction on work outcomes

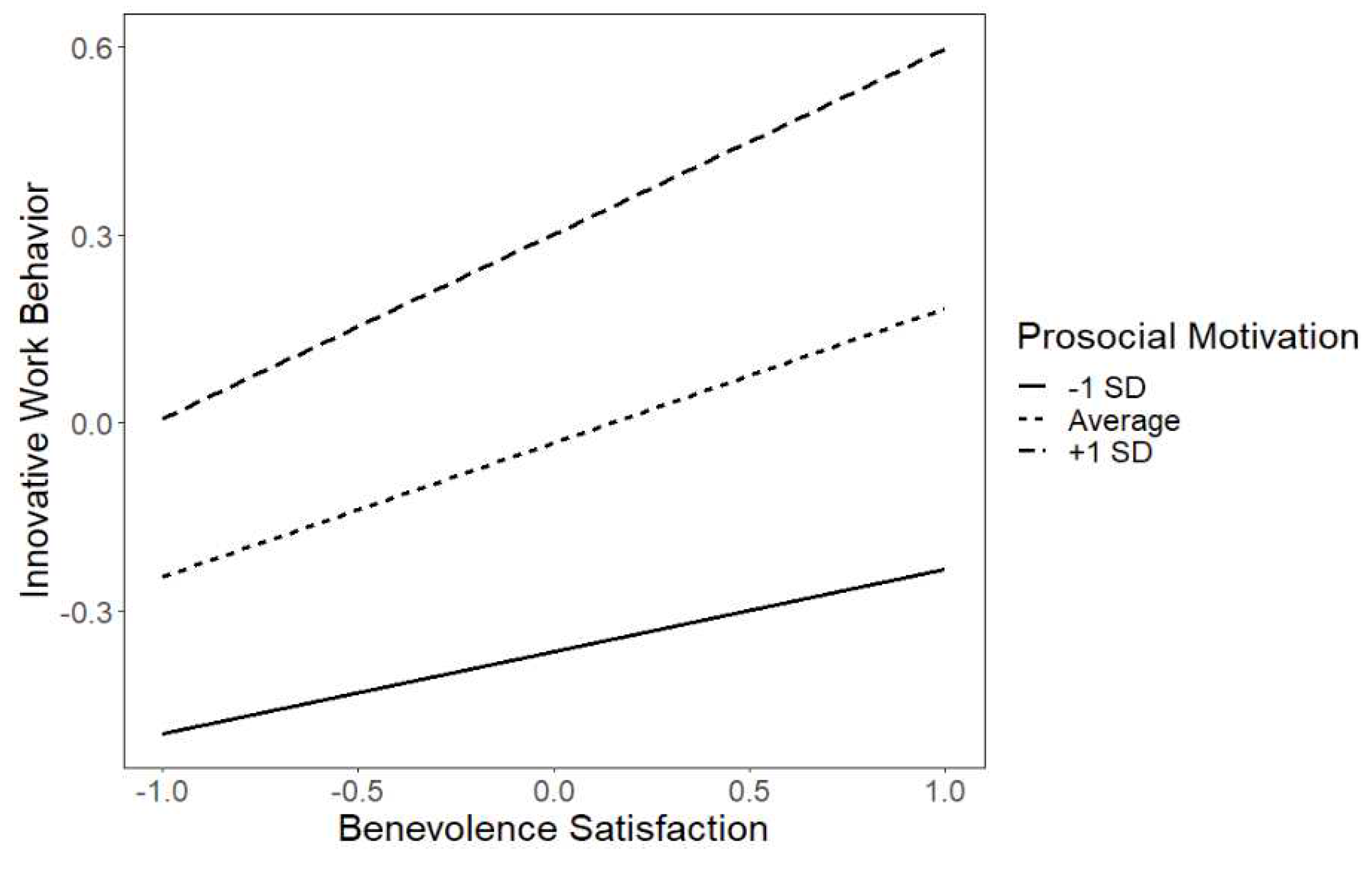

3.3. The moderating role of prosocial motivation in the relationship between benevolence satisfaction and work outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and future research

6. Practical implications and conclusion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Farrukh, M.; Meng, F.; Raza, A.; Wu, Y. Innovative Work Behaviour: The What, Where, Who, How and When. Pers. Rev. 2023, 52, 74–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, O. Job Demands, Perceptions of Effort-Reward Fairness and Innovative Work Behaviour. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2000, 73, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, J.; den Hartog, D. Measuring Innovative Work Behaviour. Creativity Innov. Manag. 2010, 19, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M. Creativity and Innovation in Organizations, 5; Harvard Business School, 1996.

- Van Dyne, L.; Jehn, K.A.; Cummings, A. Differential Effects of Strain on Two Forms of Work Performance: Individual Employee Sales and Creativity. J. Organiz. Behav. 2002, 23, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgeard, M.J.C.; Mecklenburg, A.C. The Two Dimensions of Motivation and a Reciprocal Model of the Creative Process. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2013, 17, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolino, M.C.; Grant, A.M. The Bright Side of Being Prosocial at Work, and the Dark Side, Too: A Review and Agenda for Research on Other-Oriented Motives, Behavior, and Impact in Organizations. Annals 2016, 10, 599–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A. M. Give and Take: Why Helping Others Drives Our Success; Penguin, 2014.

- Zhang, X.; Bartol, K. M. Linking Empowering Leadership and Employee Creativity: The Influence of Psychological Empowerment, Intrinsic Motivation, and Creative Process Engagement. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Dreu, C.K.W. Rational Self-Interest and Other Orientation in Organizational Behavior: A Critical Appraisal and Extension of Meglino and Korsgaard (2004). J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1245–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Berry, J.W. The Necessity of Others Is the Mother of Invention: Intrinsic and Prosocial Motivations, Perspective Taking, and Creativity. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 73–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Bai, X. Creating for Others: An Experimental Study of the Effects of Intrinsic Motivation and Prosocial Motivation on Creativity. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 23, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysova, E.I.; Allan, B.A.; Dik, B.J.; Duffy, R.D.; Steger, M.F. Fostering Meaningful Work in Organizations: A Multi-level Review and Integration. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 110, 374–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Bardi, A. Value Hierarchies Across Cultures: Taking a Similarities Perspective. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2001, 32, 268–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgeard, M. Prosocial Motivation and Creativity in the Arts and Sciences: Qualitative and Quantitative Evidence. Psychol. Aesthet. Creativity Arts. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Peng, X.; Peng, X. Influence of Prosocial Motivation on Employee Creativity: The Moderating Role of Regulatory Focus and the Mediating Role of Knowledge Sharing. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 704630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olafsen, A.H.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory and Its Relation to Organizations. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology. Olafsen, A.H., Deci, E.L., Eds.; Oxford University Press, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness (Paperback edition); Guilford Press, 2018.

- Martela, F.; Ryan, R.M. Prosocial Behavior Increases Well-Being and Vitality Even Without Contact with the Beneficiary: Causal and Behavioral Evidence. Motiv. Emot. 2016, 40, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devloo, T.; Anseel, F.; De Beuckelaer, A.; Salanova, M. Keep the Fire Burning: Reciprocal Gains of Basic Need Satisfaction, Intrinsic Motivation and Innovative Work Behaviour. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2015, 24, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messmann, G.; Evers, A.; Kreijns, K. The Role of Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction in the Relationship Between Transformational Leadership and Innovative Work Behavior. Human Resource Dev. Quarterly 2022, 33, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martela, F.; Ryan, R.M. The Benefits of Benevolence: Basic Psychological Needs, Beneficence, and the Enhancement of Well-Being. J. Pers. 84, 750–764. [CrossRef]

- Martela, F.; Riekki, T.J.J. Autonomy, Competence, Relatedness, and Beneficence: A Multicultural Comparison of the Four Pathways to Meaningful Work. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martela, F.; Ryan, R.M. Distinguishing Between Basic Psychological Needs and Basic Wellness Enhancers: The Case of Beneficence as a Candidate Psychological Need. Motiv. Emot. 2020, 44, 116–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradito Dubord, M.A.; Martin, L.; Forest, J. Bien Faire et Se Tenir en Joie: La Bienveillance, les Motivations et les Comportements des Travailleurs à la Lumière de la Théorie de l’Autodétermination. Ad machina 2022, 66–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Dreu, C.K.W.; Nijstad, B.A.; Bechtoldt, M.N.; Baas, M. Group Creativity and Innovation: A Motivated Information Processing Perspective. Psychol. Aesthet. Creativity Arts 2011, 5, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madjar, N.; Greenberg, E.; Chen, Z. Factors for Radical Creativity, Incremental Creativity, and Routine, Noncreative Performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 730–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, A.M.; Sumanth, J.J. Mission Possible? The Performance of Prosocially Motivated Employees Depends on Manager Trustworthiness. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 927–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M. Does Intrinsic Motivation Fuel the Prosocial Fire? Motivational Synergy in Predicting Persistence, Performance, and Productivity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyghebaert-Zouaghi, T.; Ntoumanis, N.; Berjot, S.; Gillet, N. Advancing the Conceptualization and Measurement of Psychological Need States: A 3 × 3 Model Based on Self-Determination Theory. J. Career Assess. 2021, 29, 396–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westfall, P.H.; Henning, K.S.S. Texts in Statistical Science: Understanding Advanced Statistical Methods; Taylor & Francis, 2013.

- Little, R.J.A. A Test of Missing Completely at Random for Multivariate Data with Missing Values. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1988, 83, 1198–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press, 2022.

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Lockwood, C.M.; Hoffman, J.M.; West, S.G.; Sheets, V. A Comparison of Methods to Test Mediation and Other Intervening Variable Effects. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team, 2023. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, version 4.3.0. Computer software. https://r-project.

- Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. J. Stat. Soft. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Parker, S.K. 7 Redesigning Work Design Theories: The Rise of Relational and Proactive Perspectives. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2009, 3, 317–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olafsen, A.H.; Deci, E.L.; Halvari, H. Basic Psychological Needs and Work Motivation: A Longitudinal Test of Directionality. Motiv. Emot. 2018, 42, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E. Method Variance in Organizational Research: Truth or Urban Legend? Organ. Res. Methods 2006, 9, 221–232. /. [CrossRef]

- Fuller, C.M.; Simmering, M.J.; Atinc, G.; Atinc, Y.; Babin, B.J. Common Methods Variance Detection in Business Research. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3192–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | N | Min | Max | Mean | SD |

| Social Impact | 549 | 1.00 | 7.00 | 4.96 | 1.35 |

| Need Satisfaction | |||||

| Autonomy | 557 | 1.00 | 7.00 | 5.25 | 1.26 |

| Competence | 557 | 1.00 | 7.00 | 5.71 | 0.98 |

| Relatedness | 557 | 1.33 | 7.00 | 5.23 | 1.14 |

| Benevolence | 556 | 1.00 | 7.00 | 5.25 | 1.07 |

| Work Outcomes | |||||

| Innovative Work Behavior | 526 | 1.00 | 6.89 | 3.72 | 1.25 |

| Creativity | 527 | 1.00 | 7.00 | 4.92 | 1.11 |

| Prosocial Motivation | 548 | 1.00 | 7.00 | 5.92 | 1.03 |

| 95% Confidence Interval | |||||||||

| Work Outcome | Need | Prosocial Motivation | Standardized Indirect Effect | p | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | Mediation? | Moderated Mediation Index | p |

| IWB | Autonomy | Low | 0.01 | .583 | -0.02 | 0.04 | No | -0.01 | .195 |

| Average | -0.01 | .559 | -0.02 | 0.01 | No | ||||

| High | -0.02 | .183 | -0.05 | 0.01 | No | ||||

| Competence | Low | 0.03 | .022 | 0.00 | 0.06 | Yes | 0.00 | .935 | |

| Average | 0.03 | .003 | 0.01 | 0.05 | Yes | ||||

| High | 0.03 | .028 | 0.00 | 0.05 | Yes | ||||

| Relatedness | Low | 0.03 | .070 | 0.00 | 0.06 | No | -0.01 | .202 | |

| Average | 0.02 | .186 | -0.01 | 0.04 | No | ||||

| High | 0.00 | .860 | -0.03 | 0.03 | No | ||||

| Benevolence | Low | 0.09 | .015 | 0.02 | 0.17 | Yes | 0.06 | .000 | |

| Average | 0.15 | .000 | 0.08 | 0.22 | Yes | ||||

| High | 0.21 | .000 | 0.14 | 0.29 | Yes | ||||

| CR | Autonomy | Low | 0.04 | .010 | 0.01 | 0.08 | Yes | 0.00 | .909 |

| Average | 0.05 | .000 | 0.02 | 0.07 | Yes | ||||

| High | 0.05 | .007 | 0.01 | 0.08 | Yes | ||||

| Competence | Low | 0.06 | .001 | 0.02 | 0.09 | Yes | 0.01 | .575 | |

| Average | 0.06 | .000 | 0.03 | 0.09 | Yes | ||||

| High | 0.07 | .000 | 0.03 | 0.10 | Yes | ||||

| Relatedness | Low | 0.01 | .718 | -0.03 | 0.04 | No | -0.01 | .495 | |

| Average | 0.00 | .911 | -0.03 | 0.02 | No | ||||

| High | -0.01 | .596 | -0.04 | 0.02 | No | ||||

| Benevolence | Low | 0.04 | .375 | -0.05 | 0.12 | No | 0.00 | .771 | |

| Average | 0.03 | .401 | -0.04 | 0.11 | No | ||||

| High | 0.03 | .513 | -0.06 | 0.11 | No | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).