Submitted:

12 September 2023

Posted:

13 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Recruitment

Molecular tests

Haematological and haematochemical parameters

Oxidative and inflammatory tests

Immunological Tests

Statistics

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Christensen, K.; Doblhammer, G.; Rau, R.; Vaupel, J.W. Ageing populations: the challenges ahead. Lancet. 2009, 374, 1196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, V.D.; Antebi, A.; Bartke, A.; Barzilai, N.; Brown-Borg, H.M.; Caruso, C.; Curiel, T.J.; de Cabo, R.; Franceschi, C.; Gems, D.; et al. Interventions to Slow Aging in Humans: Are We Ready? Aging Cell. 2015, 14, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, C.; Passarino, G.; Puca, A.; Scapagnini, G. "Positive biology": the centenarian lesson. Immun Ageing. 2012, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiello, A.; Ligotti, M.E.; Cossarizza, A. Centenarian Offspring as a Model of Successful Ageing. In Centenarians; Caruso, C., Ed.; Springer: Cham, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accardi, G.; Aiello, A.; Aprile, S.; Caldarella, R.; Cammarata, G.; Carru, C.; Caruso, C.; Ciaccio, M.; Colomba, P.; Galimberti, D.; et al. The Phenotypic Characterization of the Cammalleri Sisters, an Example of Exceptional Longevity. Rejuvenation Res. 2020, 23, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, C.; Accardi, G.; Aiello, A.; Calabrò, A.; Ligotti, M.E.; Candore, G. Centenarians born before 1919 are resistant to COVID-19. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2023, 35, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, C.; Marcon, G.; Accardi, G.; Aiello, A.; Calabrò, A.; Ligotti, M.E.; Tettamanti, M.; Franceschi, C.; Candore, G. Role of Sex and Age in Fatal Outcomes of COVID-19: Women and Older Centenarians Are More Resilient. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro, M.V.; Silva, M.V.R.; Naslavsky, M.S.; Scliar, M.O.; Nunes, K.; Passos-Bueno, M.R.; Castelli, E.C.; Magawa, J.Y.; Adami, F.L.; Moretti, A.I.S.; et al. The oldest unvaccinated Covid-19 survivors in South America. Immun Ageing. 2022, 19, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligotti, M.E.; Accardi, G.; Aiello, A.; Aprile, S.; Calabrò, A.; Caldarella, R.; Caruso, C.; Ciaccio, M.; Corsale, A.M.; Dieli, F.; et al. Sicilian semi- and supercentenarians: Identification of age-related T cell immunophenotype to define longevity trait. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2023. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasubramanian, R.; Meier, H.C.S.; Vivek, S.; Klopack, E.; Crimmins, E.M.; Faul, J.; Nikolich-Žugich, J.; Thyagarajan, B. Evaluation of T-cell aging-related immune phenotypes in the context of biological aging and multimorbidity in the Health and Retirement Study. Immun Ageing. 2022, 19, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pounis, G.; Bonaccio, M.; Di Castelnuovo, A.; Costanzo, S.; de Curtis, A.; Persichillo, M.; Sieri, S.; Donati, M.B.; Cerletti, C.; de Gaetano, G.; et al. Polyphenol intake is associated with low-grade inflammation, using a novel data analysis from the Moli-sani study. Thromb Haemost. 2016, 115, 344–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, A.; Accardi, G.; Aprile, S.; Caldarella, R.; Carru, C.; Ciaccio, M.; De Vivo, I.; Gambino, C.M.; Ligotti, M.E.; Vasto, S.; et al. Age and Gender-related Variations of Molecular and Phenotypic Parameters in A Cohort of Sicilian Population: from Young to Centenarians. Aging Dis. 2021, 12, 1773–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiello, A.; Accardi, G.; Aprile, S.; Caldarella, R.; Cammarata, G.; Carru, C.; Caruso, C.; Ciaccio, M.; De Vivo, I.; Gambino, C.M.; et al. Pro-inflammatory status is not a limit for longevity: case report of a Sicilian centenarian. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2021, 33, 1403–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinellu, A.; Mangoni, A.A. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio and disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Invest. 2023, 53, e13877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Accardi, G.; Aprile, S.; Candore, G.; Caruso, C.; Cusimano, R.; Cristaldi, L.; Di Bona, D.; Duro, G.; Galimberti, D.; Gambino, C.M.; et al. Genotypic and Phenotypic Aspects of Longevity: Results from a Sicilian Survey and Implication for the Prevention and Treatment of Age-related Diseases. Curr Pharm Des. 2019, 25, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, W.T.; Sokolowski, M.B.; Robinson, G.E. Genes and environments, development and time. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020, 117, 23235–23241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, C.; Ligotti, M.E.; Accardi, G.; Aiello, A.; Duro, G.; Galimberti, D.; Candore, G. How Important Are Genes to Achieve Longevity? Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 5635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasto, S.; Rizzo, C.; Caruso, C. Centenarians and diet: What they eat in the Western part of Sicily. Immun Ageing. 2012, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasto, S.; Scapagnini, G.; Rizzo, C.; Monastero, R.; Marchese, A.; Caruso, C. Mediterranean diet and longevity in Sicily: survey in a Sicani Mountains population. Rejuvenation Res. 2012, 15, 184–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulain, M.; Pes, G.M.; Grasland, C.; Carru, C.; Ferrucci, L.; Baggio, G.; Franceschi, C.; Deiana, L. Identification of a geographic area characterized by extreme longevity in the Sardinia island: the AKEA study. Exp Gerontol. 2004, 39, 1423–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, C.; Ligotti, M.E.; Accardi, G.; Aiello, A.; Candore, G. An immunologist's guide to immunosenescence and its treatment. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2022, 18, 961–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rea, J.N.M.; Broczek, K.M.; Cevenini, E.; Celani, L.; Rea, S.A.J.; Sikora, E.; Franceschi, C.; Fortunati, V.; Rea, I.M. Insights Into Sibling Relationships and Longevity From Genetics of Healthy Ageing Nonagenarians: The Importance of Optimisation, Resilience and Social Networks. Front Psychol. 2022, 13, 722286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasto, S.; Buscemi, S.; Barera, A.; Di Carlo, M.; Accardi, G.; Caruso, C. Mediterranean diet and healthy ageing: A Sicilian perspective. Gerontology 2014, 60, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puca, A.A.; Spinelli, C.; Accardi, G.; Villa, F.; Caruso, C. Centenarians as a model to discover genetic and epigenetic signatures of healthy ageing. Mech Ageing Dev. 2018, 174, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurinovich, A.; Andersen, S.L.; Puca, A.; Atzmon, G.; Barzilai, N.; Sebastiani, P. Varying Effects of APOE Alleles on Extreme Longevity in European Ethnicities. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2019, 74 (Suppl_1), S45–S51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, A.; Accardi, G.; Candore, G.; Gambino, C.M.; Mirisola, M.; Taormina, G.; Virruso, C.; Caruso, C. Nutrient sensing pathways as therapeutic targets for healthy ageing. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2017, 21, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, C.; Aiello, A.; Accardi, G.; Ciaglia, E.; Cattaneo, M.; Puca, A. Genetic Signatures of Centenarians: Implications for Achieving Successful Aging. Curr Pharm Des. 2019, 25, 4133–4138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horáková, D.; Štěpánek, L.; Janout, V.; Janoutová, J.; Pastucha, D.; Kollárová, H.; Petráková, A.; Štěpánek, L.; Husár, R.; Martiník, K. Optimal Homeostasis Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) Cut-Offs: A Cross-Sectional Study in the Czech Population. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019, 55, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausman, D.B.; Fischer, J.G.; Johnson, M.A. Protein, lipid, and hematological biomarkers in centenarians: definitions, interpretation and relationships with health. Maturitas. 2012, 71, 205–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawer, A.A.; Jennings, A.; Fairweather-Tait, S.J. Iron status in the elderly: A review of recent evidence. Mech Ageing Dev. 2018, 175, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passeri, G.; Vescovini, R.; Sansoni, P.; Galli, C.; Franceschi, C.; Passeri, M.; Italian Multicentric Study on Centenarians (IMUSCE). Calcium metabolism and vitamin D in the extreme longevity. Exp Gerontol. 2008, 43, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, T.R.; Chen, C.H. Bone biomarker for the clinical assessment of osteoporosis: recent developments and future perspectives. Biomark Res. 2017, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lio, D.; Malaguarnera, M.; Maugeri, D.; Ferlito, L.; Bennati, E.; Scola, L.; Motta, M.; Caruso, C. Laboratory parameters in centenarians of Italian ancestry. Exp Gerontol. 2008, 43, 119–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.A.; Sánchez-Lozada, L.G.; Johnson, R.J.; Kang, D.H. Oxidative stress with an activation of the renin-angiotensin system in human vascular endothelial cells as a novel mechanism of uric acid-induced endothelial dysfunction. J Hypertens. 2010, 28, 1234–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ridi, R.; Tallima, H. Physiological functions and pathogenic potential of uric acid: A review. J Adv Res. 2017, 8, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siino, V.; Ali, A.; Accardi, G.; Aiello, A.; Ligotti, M.E.; Mosquim, S.J.; Candore, G.; Caruso, C.; Levander, F.; Vasto, S. Plasma proteome profiling of healthy individuals across the life span in a Sicilian cohort with long-lived individuals. Aging Cell 2022, 21, e13684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accardi, G.; Ligotti, M.E.; Candore, G. Phenotypic Aspects of Longevity. In Centenarians; Caruso, C., Ed.; Springer: Cham, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, C.; Bonafè, M.; Valensin, S.; Olivieri, F.; De Luca, M.; Ottaviani, E.; De Benedictis, G. Inflamm-aging. An evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2000, 908, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, C.; Accardi, G.; Aiello, A.; Calabrò, A.; Ligotti, M.E.; Candore, G. Lessons from Sicilian Centenarians for Anti-Ageing Medicine. The Oxi-Inflammatory Status. Transl Med UniSa. 2022, 24, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Garlanda, C. Humoral Innate Immunity and Acute-Phase Proteins. N Engl J Med. 2023, 388, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accardi, G.; Bono, F.; Cammarata, G.; Aiello, A.; Herrero, M.T.; Alessandro, R.; Augello, G.; Carru, C.; Colomba, P.; Costa, M.A.; et al. miR-126-3p and miR-21-5p as hallmarks of bio-positive ageing; correlation analysis and machine learning prediction in young to ultra-centenarian Sicilian population. Cells. 2022, 11, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinti, M.; Gibellini, L.; Lo Tartaro, D.; De Biasi, S.; Nasi, M.; Borella, R.; Fidanza, L.; Neroni, A.; Troiano, L.; Franceschi, C.; et al. A Comprehensive Analysis of Cytokine Network in Centenarians. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Ge, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Leng, M.; Gan, C.; Mou, Y.; Zhou, J.; Valencia, C.A.; Hao, Q.; et al. Centenarians alleviate inflammaging by changing the ratio and secretory phenotypes of T helper 17 and regulatory T cells. Front Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 877709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arai, Y.; Martin-Ruiz, C.M.; Takayama, M.; Abe, Y.; Takebayashi, T.; Koyasu, S.; Suematsu, M.; Hirose, N.; von Zglinicki, T. Inflammation, but not telomere length, predicts successful ageing at extreme old age: A longitudinal study of semi-supercentenarians. EBioMedicine 2015, 2, 1549–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Listì, F.; Candore, G.; Modica, M.A.; Russo, M.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Esposito-Pellitteri, M.; Colonna-Romano, G.; Aquino, A.; Bulati, M.; Lio, D.; et al. A study of serum immunoglobulin levels in elderly persons that provides new insights into B cell immunosenescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006, 1089, 487–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, I.S.; Baeten, D.L.P.; den Dunnen, J. The inflammatory function of human IgA. Cell Mol Life Sci 76, 1041–1055. [CrossRef]

- Ligotti, M.E.; Aiello, A.; Accardi, G.; Aprile, S.; Bonura, F.; Bulati, M.; Gervasi, F.; Giammanco, G.M.; Pojero, F.; Zareian, N.; et al. Analysis of T and NK cell subsets in the Sicilian population from young to supercentenarian: The role of age and gender. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2021, 205, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, K.; Kouno, T.; Ikawa, T.; Hayatsu, N.; Miyajima, Y.; Yabukami, H.; Terooatea, T.; Sasaki, T.; Suzuki, T.; Valentine, M.; et al. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals expansion of cytotoxic CD4 T cells in supercentenarians. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci. USA 2019, 116, 24242–24251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagiannis, T.T.; Dowrey, T.W.; Villacorta-Martin, C.; Montano, M.; Reed, E.; Belkina, A.C.; Andersen, S.L.; Perls, T.T.; Monti, S.; Murphy, G.J.; et al. Multi-modal profiling of peripheral blood cells across the human lifespan reveals distinct immune cell signatures of aging and longevity. EBioMedicine 2023, 90, 104514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, S.L.; Sebastiani, P.; Dworkis, D.A.; Feldman, L.; Perls, T.T. Health span approximates life span among many supercentenarians: compression of morbidity at the approximate limit of life span. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012, 67, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | A.T. | Young Adults N = 29 | Centenarians N = 22 |

|---|---|---|---|

| APOE | N alleles | N alleles | N alleles |

| ε3 | 2 | 5 | 4 |

| ε2 | 49 | 39 | |

| ε4 | 4 | 1 | |

| FOXO3A rs2802292 | N alleles | N alleles | N alleles |

| G | 25 | 17 | |

| T | 2 | 33 | 27 |

| Variable (Unit) | Values | Laboratory Reference Range Value |

|---|---|---|

| Red Blood Cells (106µL) | 4.39 | 4.20-5.50 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.70 | 12.00-18.00 |

| Platelets (103µL) | 230 | 150-450 |

| Leukocytes (103µL) | 7.61 | 4.00-11.00 |

| Neutrophils (103 µL) | 4.12 | 2.00-8.00 |

| Eosinophils (103 µL) | 0.37 | 0.00-0.80 |

| Basophils (103 µL) | 0.05 | 0.00-0.20 |

| Monocytes (103 µL) | 0.94 | 0.16-1.00 |

| Lymphocytes (103 µL) | 2.12 | 1.00-5.00 |

| CD3 (103/μL) | 1.25 | 0.81-2.13 |

| CD4 (103/μL) | 0.70 | 0.02-1.88 |

| CD8 (103/μL) | 0.51 | 0.06-0.74 |

| Variable (unit) | Values | Laboratory Reference Range Value |

|---|---|---|

| ENDOCRINE MARKERS | ||

| TSH (µIU/mL) | 0.56 | 0.27-4.20 |

| FT3 (pg/mL) | 2.65 | 2.00-4.40 |

| FT4 (ng/dL) | 1.31 | 0.93-1.70 |

| Insulin (µU/mL) | 3.28 | 2.60-24.90 |

| HOMA Index | 0.56 | 0.47-3.19 |

| Glycaemia (mg/dL) | 69 | 70-100 |

| LIVER MARKERS | ||

| ALT (U/L) | 13 | <41 |

| AST (U/L) | 23 | <40 |

| GGT (U/L) | 53 | 8-61 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.85 | <1.20 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 33.4 | 38-48 |

| Proteins (g/L) | 58.6 | 66-87 |

| IRON MARKERS | ||

| Iron (µg/dL) | 85 | 37-145 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 91 | 15-400 |

| Transferrin (mg/dL) | 266 | 200-360 |

| LIPID MARKERS | ||

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 133 | <200 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 64.4 | >65 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 56 | >50 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 63 | <200 |

| BONE MARKERS | ||

| Osteocalcin ng/mL | 33.4 | 14.00-46.00 |

| ALP (U/L) | 175 | 40-129 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 8.61 | 8.40-10.20 |

| Magnesium (mg/dL) | 2.13 | 1.60-2.60 |

| Vitamin D (ng/mL) | 3.75 | (>30) |

| CATABOLIC PARAMETERS | ||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.01 | 0.5-1.2 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 33.5 | 16.8-48.5 |

| Variable (unit) | Values | Laboratory Reference Range Values |

|---|---|---|

| LDL Ox (mIU/ml) | 47 | 44.6-87.3 |

| Uric Acid (mg/dL) | 6.0 | 2.4-7.0 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 3.37 | <5 mg/dL |

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | 17,8 | <7pg/ml |

| NLR | 1,95 | 0.92-2.84 |

| PLR | 108,02 | 074.71-193.34 |

| INFLA-score | 8 | -1.25* |

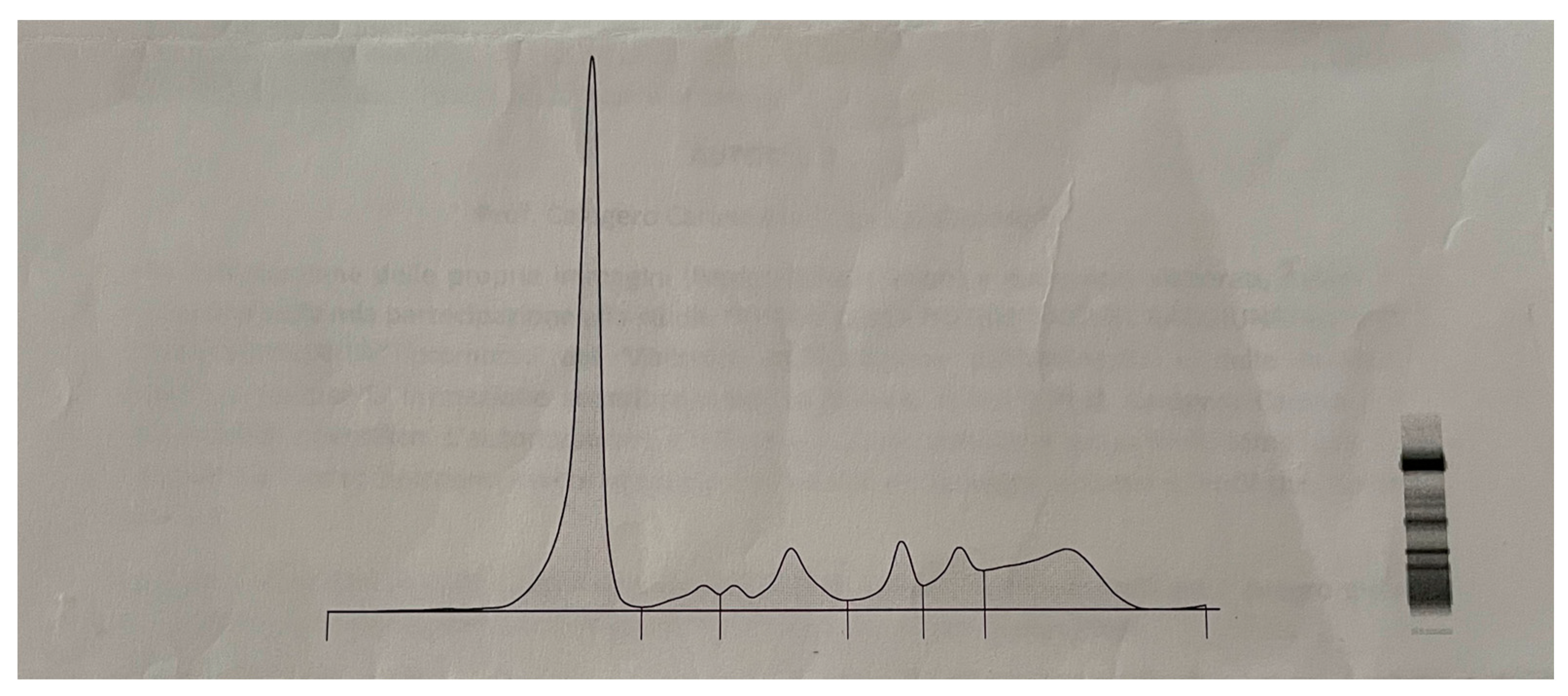

| Variable (unit) | Values | Laboratory Reference Range Values |

|---|---|---|

| IgG (mg/dL) | 1145 | 700-1600 |

| IgA(mg/dL) | 551 | 70-400 |

| IgM (mg/dL) | 94.2 | 40-230 |

| CD4+ Naive (CD45RA+CD27+) (%) | 24.0 | 4-57 |

| CD8+ Naive (CD45RA+CD27+) (%) | 9 | 10-78 |

| CD4/CD8 | 1.37 | 0.85-5.04 |

| TN/TM (CD4) | 0.32 | 0-05-1.35 |

| TN/TM (CD8) | 0.10 | 0.11-3.48 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).