1. Introduction

Interferon-induced transmembrane proteins (IFITMs) are a family of small transmembrane proteins that restrict the entry of diverse enveloped viruses and modulate essential cellular processes [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Of the five known human IFITM family members, IFITM1, IFITM2, and IFITM3 inhibit a wide range of enveloped viruses, including some of the clinically important pathogens, such as HIV-1, Ebola, Influenza A, and Dengue viruses [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. IFITMs are active against viruses that enter cells through both pH-independent and pH-dependent mechanisms, albeit to a varying degree of efficiency [

3,

6,

16,

17]. Accumulating evidence suggests that these proteins block virus entry by making the host cell membranes more rigid and imposing unfavorable membrane curvature that traps viral fusion at a hemifusion stage [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. However, intriguingly, IFITMs have little or no effect on the Murine Leukemia Virus and arenaviruses, such as the Lassa virus and lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus [

26,

27,

28]. Furthermore, few studies have reported that IFITMs can promote the infection of the human papillomavirus 16 [

28], Aichi picornavirus [

29], and human coronavirus OC43 [

30,

31].

In addition to inhibition of viral fusion when expressed in target cells, IFITM proteins expressed in infected cells incorporate into progeny virions from diverse virus families and inhibit their infectivity [

11,

12,

21,

23] via a poorly understood mechanism [

32]. This reduction of infectivity has been dubbed “negative imprinting” because the loss of infectivity does not strictly correlate with the levels of IFITM incorporation into virions [

23,

32,

33,

34]. There is disagreement regarding whether the virus’ sensitivity to “negative imprinting” is linked to viral glycoproteins or the mode of virus assembly [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36].

The HIV-1 sensitivity to IFITMs maps to the Env glycoprotein [

12,

21,

37,

38,

39]. Envs from different HIV-1 strains show differential susceptibility to virion-incorporated and target cell-expressed IFITMs [

21,

40,

41,

42] and are thus classified as sensitive or resistant Envs. The interaction between IFITM3 and HIV-1 Env in virus-producing cells inhibits the incorporation and proteolytic cleavage of the gp160 precursor, leading to reduced levels of active (processed) Env in virions [

21,

41,

43]. In addition, IFITM3 incorporation into viral particles has been reported to favor a partially open conformation of sensitive Env, thus sensitizing the virus to neutralizing antibodies and Env-targeting compounds [

34,

37].

On average, an HIV-1 particle bears only ∼8-14 Env trimers [

44,

45,

46]. Given the sparsity of Env glycoproteins, it has been proposed that Env clustering on virions is essential for infectivity [

47], as these clusters may serve as hotspots for efficient HIV-1 fusion [

48,

49,

50]. Indeed, whereas the Env mobility on immature particles is likely restricted through Env-Gag interactions, super-resolution microscopy studies have detected the formation of Env clusters following HIV-1 maturation [

47,

51,

52].

Our previous super-resolution imaging results suggested that virus-incorporated SERINC5, another host factor that restricts HIV-1 fusion through incorporation into virions, disrupts Env clusters [

39]. We therefore asked whether IFITM incorporation can reduce HIV-1 infectivity by disrupting the maturation-dependent Env clustering. Given the high degree of IFITM2 and IFITM3 sequence homology, their localization to endosomes and a similar range of restricted viruses [

8,

53], we focused on IFITM1 and IFITM3 proteins. The effect of IFITM1 and IFITM3 incorporation on Env glycoprotein clustering was assessed using direct stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (dSTORM). We find that neither IFITM1 nor IFITM3 significantly disrupts Env clusters. However, expression of IFITM3, but not IFITM1, in virus-producing cells inhibits Env processing and incorporation into virions. These findings support distinct mechanisms of restriction of HIV-1 infection by IFITM1 and IFITM3 proteins expressed in virus-producing cells and suggest that “negative imprinting” of HIV-1 infectivity is not through disruption of Env clustering.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines, Plasmids, and Reagents

Human embryonic kidney HEK293T/17 cells were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). HeLa-derived TZM-bl cells (donated by Drs. J.C. Kappes and X. Wu [

54]) were received from the NIH HIV Reagent Program. The cells were cultured in high-glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Corning, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Atlanta Biologicals, Flowery Branch, GA, USA) and 100 units/mL penicillin/streptomycin (Gemini Bio-Products, West Sacramento, CA, USA). The HEK293T/17 cells growth medium was supplemented with 0.5 mg/mL of Geneticin (Life Technologies, Inc., Grand Island, NY, USA).

The pCAGGS plasmid bearing the full-length HXB2 Env was kindly provided by Dr. J. Binley (Torrey Pines Institute, CA, USA) [

55]. The GFP-Vpr plasmid was a gift from Dr. T. Hope (Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA). The pR9ΔEnvΔNef HIV-1-based packaging vector and pcRev, have been described previously [

38]. pQCXIP vector-based constructs encoding human IFITM1 and IFITM3 were a gift from Dr. A.L. Brass [

27].

The viral protease inhibitor, Saquinavir (SQV), human HIV-1 immunoglobulin (HIV IG), anti-p24 capture antibody 183-H12-5C (CA183), Chessie 8 mouse mAb for gp41 (Produced from HIV-1 gp41 Hybridoma cells (Cat#526), and monoclonal antibody (2G12) to HIV-1 gp120 were obtained from the NIH HIV Reagent Program. Other antibodies used were rabbit recombinant antibody for IFITM3 (Abcam, USA, cat. no. ab109429), rabbit anti-IFITM1 (Sigma, USA, cat. no. HPA004810), goat anti-HIV gp120 (Fitzgerald, USA, cat. no. 20HG-81), goat anti-human IgG HRP (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA, cat. no. 31412), mouse anti-rabbit IgG HRP (Millipore, USA, cat. no. AP188P), rabbit anti-mouse IgG HRP (EMD Millipore, USA, cat. No. AP160P), donkey anti-goat IgG HRP (Santa Cruz, USA, cat. no. sc-2020), and goat anti-human IgG (H+L) conjugated with AlexaFluor 647 (AF647, ThermoFisher, cat. No. A21445). A 16% paraformaldehyde stock was purchased from ThermoFisher (cat. No. 28906). The DMEM without phenol red was obtained from Life Technologies.

2.2. Pseudovirus Production and Characterization

HIV-1 pseudoviruses were produced by transfecting HEK293T/17 cells using JetPRIME transfection reagent (Polyplus-transfection, SA, NY, USA), as described previously [

38]. HEK293T/17 cells grown in a 6-well tissue culture plates were transfected with pCAGGS-HXB2 Env (0.6 μg), pR9ΔEnvΔNef (0.8 μg), eGFP-Vpr (0.14 μg), pcRev (0.2 μg) or 0.3 μg of either pQCXIP-IFITM1, pQCXIP-IFITM3 or empty pQCXIP expression vectors. To produce immature viruses, 300 nM of SQV was added to a growth medium, as indicated. The transfection medium was replaced with phenol-free DMEM/10%FBS after 10-12 h, and the cells were further incubated for an additional 34-36 h at 37 °C, 5% CO

2 incubator, after which, the virus-containing culture medium was collected, passed through a 0.45 μm filter, and concentrated 10× using Lenti-X concentrator (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA). The virus was precipitated after an overnight concentration with Lenti-X by centrifuging at 1500×

g for 45 minutes at 4 °C, resuspended in PBS, and kept at -80 °C.

2.3. ELISA Assay and Western Blotting

The p24 content of pseudoviruses was determined by ELISA assay, as previously described [

56]. p24 normalized pseudoviruses were lysed using 2X Laemmli buffer (Bio-Rad, USA). The samples were loaded onto 4-15% polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad, CA, USA) and blotted onto 0.45 μm nitrocellulose membrane (Cytiva, MA, USA). The membranes were blocked with 10% dry milk in 0.1% Tween 20 in phosphate-buffered saline solution. The membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with different primary antibodies as follows: HIV IG (1:2000 dilution), rabbit anti-IFITM1 (1:500 dilution), a recombinant anti-fragilis antibody for IFITM3 (1:1000), mouse and mouse anti-HIV gp41 (1:10). Secondary antibody staining was performed using either goat anti-human HRP, mouse anti-rabbit HRP, or rabbit anti-mouse HRP for 1 h at room temperature using a dilution of 1:3000. The chemiluminescence signal was recorded on ChemiDoc XRS+ (Bio-Rad) using Image Lab version 5.2 software and analyzed using Image Lab 5.2 software.

2.4. Infectivity Assay

To determine the infectivity of HIV-1 pseudoviruses, TZM-bl cells were seeded into black clear-bottom 96-well plates. The cells were infected with serially diluted pseudoviruses and centrifuged at 4 °C for 30 min at 1550× g to aid virus attachment to cells. The infectivity was measured 48 h post-infection by lysing the samples with the Bright-Glo luciferase substrate (Promega, WI, USA) at room temperature and immediately reading the luciferase signal using a TopCount NXT reader (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, CT, USA). The results were subsequently normalized to the p24 values. The analysis of infectivity data was done using an unpaired Student’s t-test implemented in GraphPad Prism version 9.3.1 for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla CA, USA).

2.5. Immunostaining and dSTORM Sample Preparation

Eight chambered glass coverslips (#1.5, Lab-Tek, Nalge Nunc International, Penfield, NY) were coated with the 0.1 mg/mL poly-D-lysine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and 100 nm gold nanoparticles (Cytodiagnostics, G-100−20) according to the previously described protocol [

39]. The pseudoviruses diluted in PBS

++ (30-fold) were attached to pre-treated coverslips for 30 minutes at room temperature. Unbound pseudoviruses were removed by washing and attached pseudoviruses were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde solution in PBS

++ for 30 minutes at room temperature in the dark. Excess paraformaldehyde was quenched by washing samples with 20 mM Tris in PBS

++. The samples were blocked with 15% FBS in PBS

++ for 2 h at room temperature. The FBS solution was removed, and the samples were incubated overnight with primary monoclonal antibody to HIV-1 gp120 (2G12, 5 μg/mL) at 4 °C. The samples were washed with 15% FBS (9 times) and incubated with the secondary goat anti-human AlexaFluor-647 (2 μg/mL) antibody for 1 h at room temperature. The samples were washed 9 times with PBS

++ and were further used for immunofluorescence imaging and dSTORM experiments. Virus aggregation had no significant impact on our analysis, as evidenced by a very weak correlation (using Pearson coefficient) between Env and GFP-Vpr signals for all four pseudovirus preparations (data not shown).

2.6. Wide-Field Fluorescence and dSTORM Imaging

Initially, the immunostained pseudoviruses were imaged using a wide-field microscope (Elite DeltaVision (Leica Microsystems, Inc., Deerfield, IL, USA). The UPlanFluo 40X/1.3 NA oil objective (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and DAPI/FITC/TRITC/Cy5 Quad cube filter sets (Chroma, Bellows Falls, VT) were used for the imaging.

For dSTORM imaging, the stock solutions of Tris-NaCl buffer, an oxygen scavenging system (GLOX), catalase, and methyl ethylamine were prepared using the Nikon STORM sample preparation protocol [

57]. These stock solutions were kept at 4 °C and used within 1–2 weeks of preparation. For experiments, the above-mentioned buffers were immediately mixed in a 90:9:1 ratio to avoid buffer acidification (for each sample every 2 h), as described previously [

58]. The imaging buffer was added to the sample, and the glass coverslips were sealed with parafilm to limit the oxygen exchange. dSTORM imaging was performed on an Oxford ONI super-resolution microscope (Nanoimager, San Diego, CA, USA). The imaging was done using a 638 nm laser with a 50 ms frame rate, for a total of 20k frames. The power of a 405 nm laser was adjusted to 0.2 mW to increase the blinking rate of AF647. SMLs with photon count of more than 1000 and localization precision less than 20 nm were considered for analysis.

Image drift correction was performed using the previously published protocol [

39] with at least three immobilized fiducial gold nanoparticles in the imaging field. GFP-Vpr particles with fewer than 20 AF647 SMLs were excluded from analysis to eliminate the background signal.

2.7. DBCAN Analysis

Coverslip-adhered pseudovirions were identified based on the GFP-Vpr fluorescence signal. The coordinates of the single-molecule localizations (SMLs) were assigned to a virus, using a search radius of 200 nm from the center of a GFP spot. Clustering analysis was performed using density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise (DBSCAN), as described previously [

59], using a custom MATLAB script. This algorithm identifies SML clusters based on two user-selectable parameters: the search radius (R) and the minimum number of SMLs (N) within that radius [

60,

61]. The R of 15 nm appears optimal for selecting smaller and denser clusters at higher SML thresholds [

39]. For our analysis of dSTORM images, the threshold was set to R = 15 nm.

2.8. Data Processing and Statistical Analyses

For analyzing the immunostaining data, a custom MATLAB script was used to identify GFP-Vpr-labeled pseudoviruses by finding local maxima with a fast 2D peak finder. A specific signal-to-background ratio was fixed to eliminate the faint signals. The coordinates of GFP-Vpr and AF647 were used to quantify the Env fluorescence signals associated with the particles.

The R software was used for the statistical analysis of categorized clustering data (1, 2, >2 clusters or no clusters) using Fisher’s Exact Test. Distributions of single-molecule localizations per virion measured by 2D dSTORM were analyzed using a custom MATLAB script for two-sample Kolmogorov−Smirnov (KS) test. To alleviate the effect of a very large sample size for SML data, the results were binned using an optimal bin width set to represent each sample population [

59]. Where indicated, to emulate the effect of sample size reduction, we applied optimal binning to the SML data (n > 100 points) sets using the following equation: W (bin width) = 2 (3rd quantile −1st quantile) × N

−1/3. The pairwise distance analysis of SMLs on single pseudoviruses was done using

pdist. MATLAB function. The statistics were done in MATLAB using a two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) non-parametric test.

Finally, two-way repeated measures beta regression models were employed to determine whether Env clustering differs between the viruses in a panel (e.g., control vs. SQV), for virions with different numbers of clusters (i.e., no clusters, 1, 2, 2+ clusters), and over three biological replicates. These regression models included virus treatment and the number of clusters as main effects, along with their two-way interaction. These regression models were calculated in the full dataset and stratified by SML thresholds (≥20, ≥60, ≥90), and p-values are presented unadjusted. As outcome proportions in our data were often inclusive of 0%, and beta regression requires outcome values to be greater than 0% and less than 100%, we added a transformation, described by Smithson & Verkuilen [

62], to our outcome proportions prior to any regression analysis. Beta regression analysis was carried out in SAS v.9.4 (Cary, NC), and statistical significance was evaluated at the 0.05 threshold.

3. Results

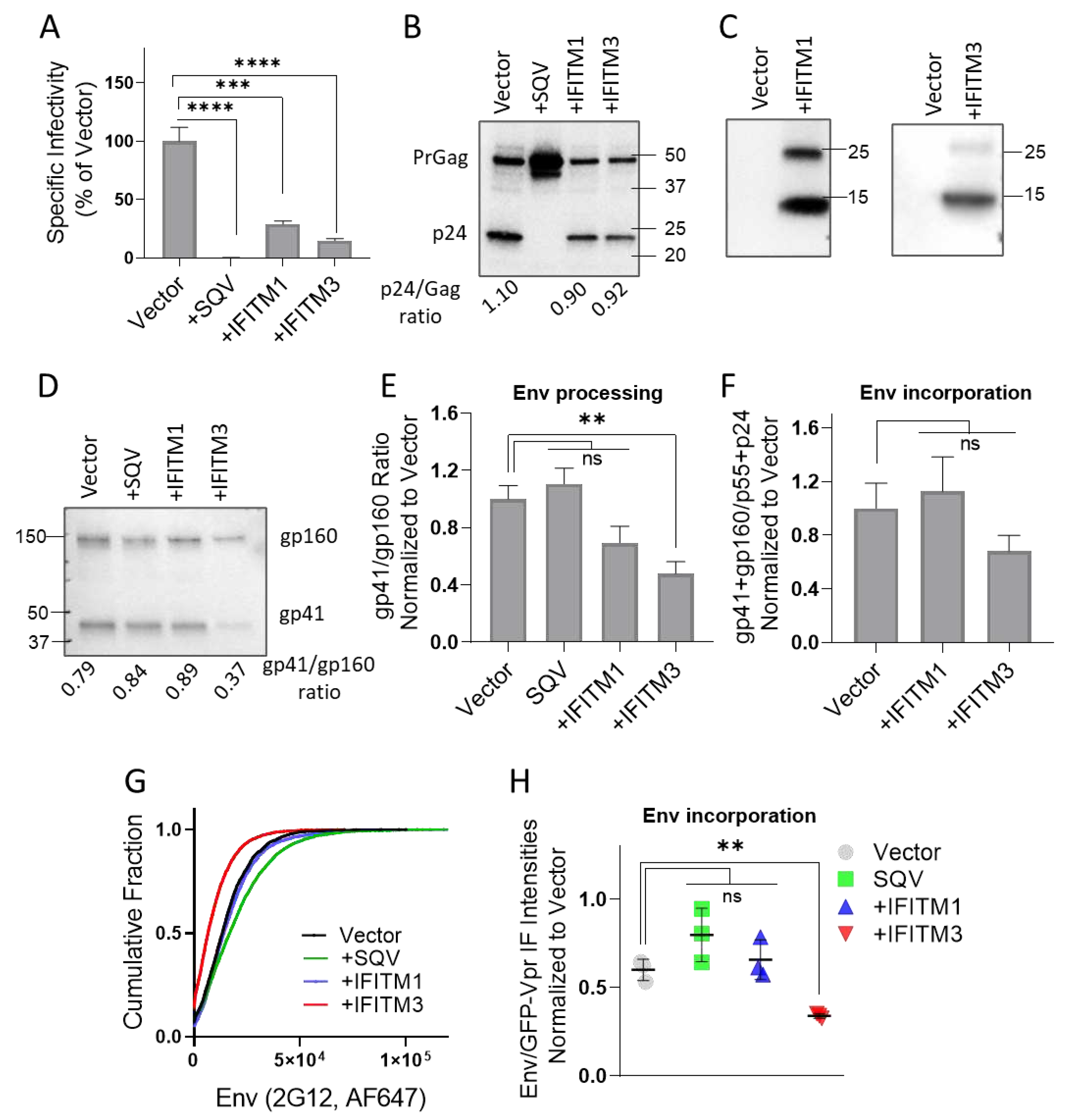

3.1. IFITM1 and IFITM3 Incorporation into HIV-1 Pseudoviruses Inhibits Infectivity but Only IFITM3 Interferes with Env Glycoproteins Processing and Incorporation

To assess the effect of virus-incorporated IFITMs on Env distribution on pseudovirions, we prepared three independent panels of GFP-Vpr labeled pseudoviruses containing the IFITM-sensitive HXB2 Env, as described in Methods. Each panel included four viral preparations produced in control 293T cells, as well as in cells expressing IFITM1 or IFITM3. Immature pseudoviruses produced in the presence of the HIV-1 protease inhibitor SQV were included as a control for virus maturation-driven Env clustering reported previously [

39,

51,

63].

The infectivity of pseudovirus panels was tested on HeLa-derived TZM-bl cells, ectopically expressing CD4 and CCR5, along with endogenous levels of CXCR4 [

64]. IFITM1 and IFITM3 expression in producer cells strongly reduced the HIV-1 infectivity (

Figure 1A), in good agreement with the previously published studies [

11,

12,

37,

48]. We found that maturation (Gag processing) of pseudoviruses produced by IFITM1 or IFITM3 expressing cells was not altered compared to control, while Gag cleavage was blocked by SQV, as expected (

Figure 1B and

Figure S1A,S1E). Both IFITMs were efficiently incorporated into pseudoviruses, as evidenced by prominent IFITM1 and IFITM3 bands on immunoblots of concentrated virus lysates (

Figure 1C and

Figure S1B,S1F).

We next tested whether reduced infectivity of IFITM-containing pseudoviruses was caused by diminished Env processing or incorporation into viral particles. IFITM3, but not IFITM1 expression in virus producing cells significantly lowered the proteolytic processing of the virus-incorporated gp160 precursor (

Figure 1D and

Figure S1C,S1G), in good agreement with the previous studies [

21,

43]. Inhibition of gp160 processing by IFITM3 was observed across three independent panels of viruses, while reduction of Env cleavage in IFITM1 pseudoviruses did not reach statistical significance (

Figure 1E). IFITM3 expression also tended to diminish HIV-1 Env incorporation into pseudoviruses, as measured by immunoblotting (

Figure 1D and

Figure S1C,S1G). However, the decrease in HIV-1 Env incorporation in IFITM3-containing pseudoviruses across multiple panels was not statistically significant (

Figure 1F).

To further assess the effect of IFITMs on Env incorporation on a single particle level, we performed immunofluorescence staining of GFP-Vpr labeled pseudovirions. Pseudoviruses adhered to glass coverslips were fixed and incubated with human anti-Env antibody (2G12), followed by staining with a secondary antibody conjugated with AlexaFluor-647 (AF647). All virus preparations contained comparable levels of GFP-Vpr (data not shown), whereas analysis of single virus immunofluorescence revealed a weaker Env signal for IFITM3-containing particles compared to control and IFITM1 pseudoviruses (

Figure 1G and

Figure S1D,S1H). The less efficient Env incorporation into IFITM3 containing pseudoviruses was observed across three independent virus preparations (

Figure 1H), in general agreement with our immunoblotting results.

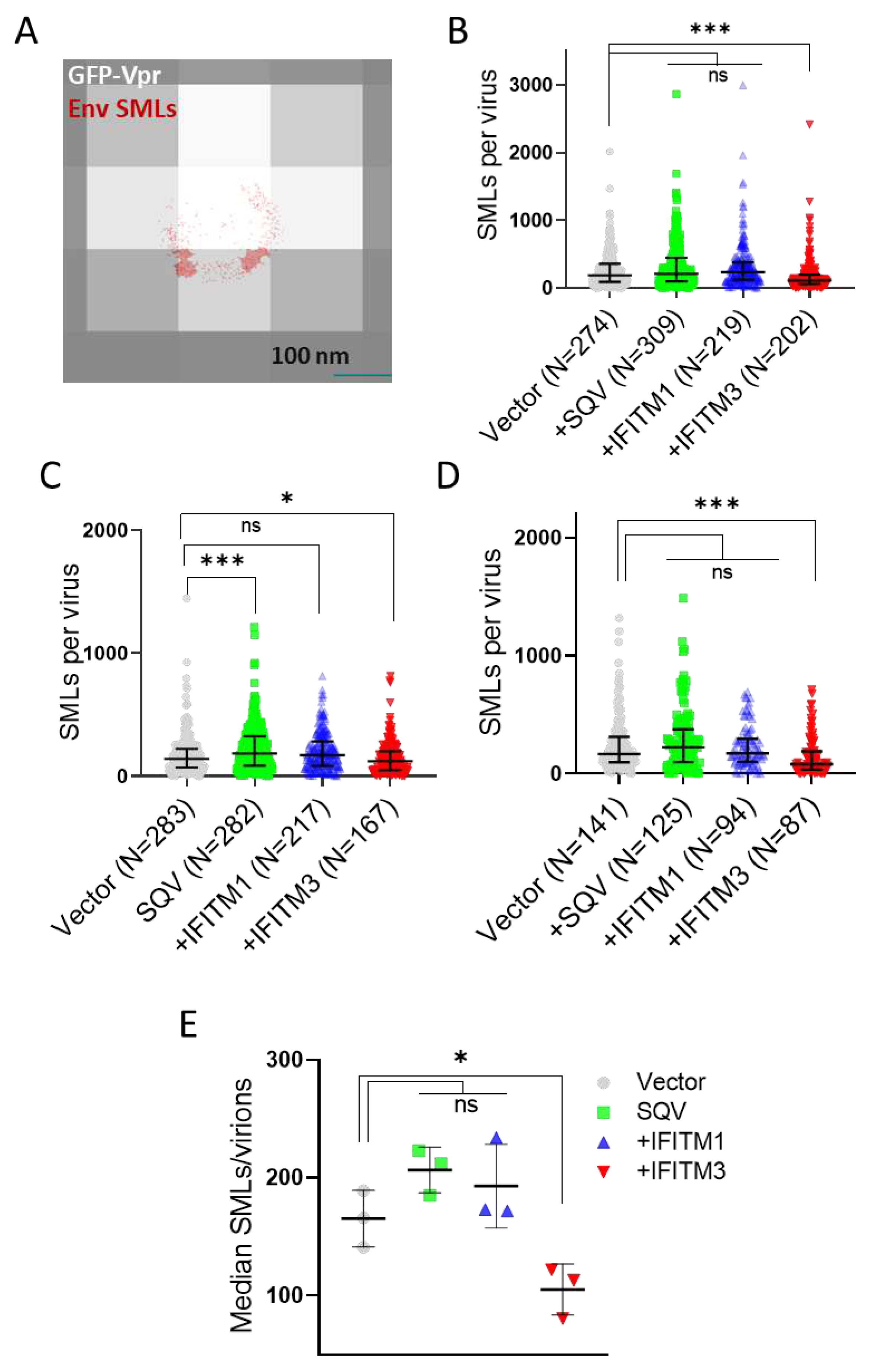

3.2. IFITM3 Incorporation Does Not Consistently Perturb Env Clustering on HIV-1 Particles

We next visualized the distribution of Env on HIV-1 GFP-Vpr labeled pseudoviruses by direct stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (dSTORM). The imaging experiments were carried out on an Oxford Nanoimager microscope using the illumination of 638 nm and 405 nm lasers to visualize the stochastic blinking of AF647 stained Env associated with each GFP-Vpr spot (see Methods for details). Single-molecule Env localizations (in red) overlaid onto diffraction-limited images of GFP-Vpr (gray) (

Figure 2A) reveal a non-uniform Env distribution on virions, with a tendency to form clusters. Consistent with the reduced Env signals in immunoblots and in wide-field fluorescence imaging of single virions, overall fewer SMLs were detected by dSTORM on IFITM3 pseudoviruses for three independent biological replicates (

Figure 2B–D). Only in one viral preparation out of three, the SML distribution associated with SQV treated pseudoviruses significantly differed from the control sample. Lower median SMLs were detected for IFITM3 pseudoviruses compared to other pseudoviruses in independent panels (

Figure 2E). To ensure that a statistically significant reduction in the Env SMLs for IFITM3 containing particles was not a result of large sample size, we applied the optimal binning protocol to our data [

59]. This approach confirmed that pseudoviruses produced by IFITM3, but not IFITM1 expressing cells had, on average, fewer SMLs than control particles (

Figure S2).

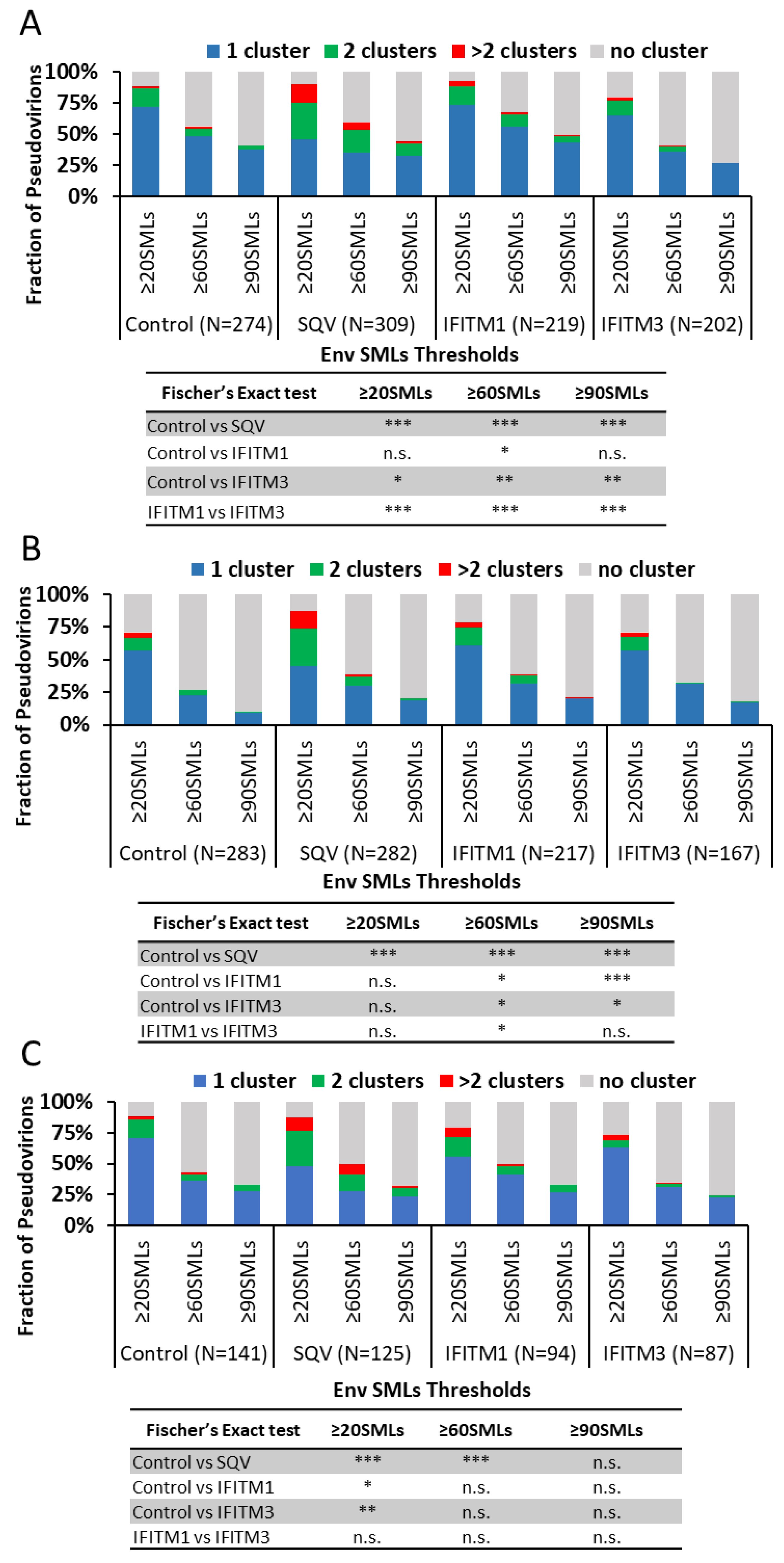

Env clustering on pseudoviruses was analyzed using the DBSCAN algorithm, which defines SML clusters based upon a user-selected minimal number of SMLs within a search radius [

39,

60]. For DBSCAN analysis, we kept the search radius constant (R = 15 nm), while varying the SMLs threshold (N) between 20 and 90. From DBSCAN analysis of our dSTORM data, the virions were classified into four categories: virions with no clusters, one cluster, two clusters, and more than two clusters. The relative fractions of virions in each category were plotted as a function of SML thresholds (

Figure 3). The more stringent the SML thresholding resulted in a lower fraction of virions with Env clusters. This analysis revealed that immature particles contained a greater number of multiple clusters relative to control virions for all three viral preparations (

Figure 3A–C), in agreement with the previous studies using stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy and dSTORM [

39,

51]. On average, a smaller fraction of IFITM3-containing pseudoviruses exhibited Env clusters compared to control samples (

Figure 3A–C). However, the IFITM effects on Env clustering varied between independent preparations and within preparations as a function of the SML thresholds. The inconsistency of statistical significance of the IFITM-mediated effects across our samples is suggestive of the lack of robust disruption of Env clusters by these proteins.

To simplify our clustering analysis, we also considered just two categories of viruses—those with and without clusters (regardless of the number of Env clusters). Similar to the four-category analysis above, the fraction of viruses with Env clusters diminished for the more stringent SML thresholds (

Figure S3). Here too, varied degrees of Env cluster disruption by IFITMs were observed for three independent pseudovirus panels—from no effect across the SML thresholds to significant inhibition of Env clustering (

Figure S2A–C). We also examined the effects of IFITMs on the pairwise distance distributions between all Env SMLs within each single particle. Two out of three preparations showed overlapping distributions of the Env-Env distances for the entire pseudovirus panel, while significantly shorter pairwise Env SML distances for IFITM1 and IFITM3 containing particles compared to control were observed for one pseudovirus preparation (

Figure S3A–C).

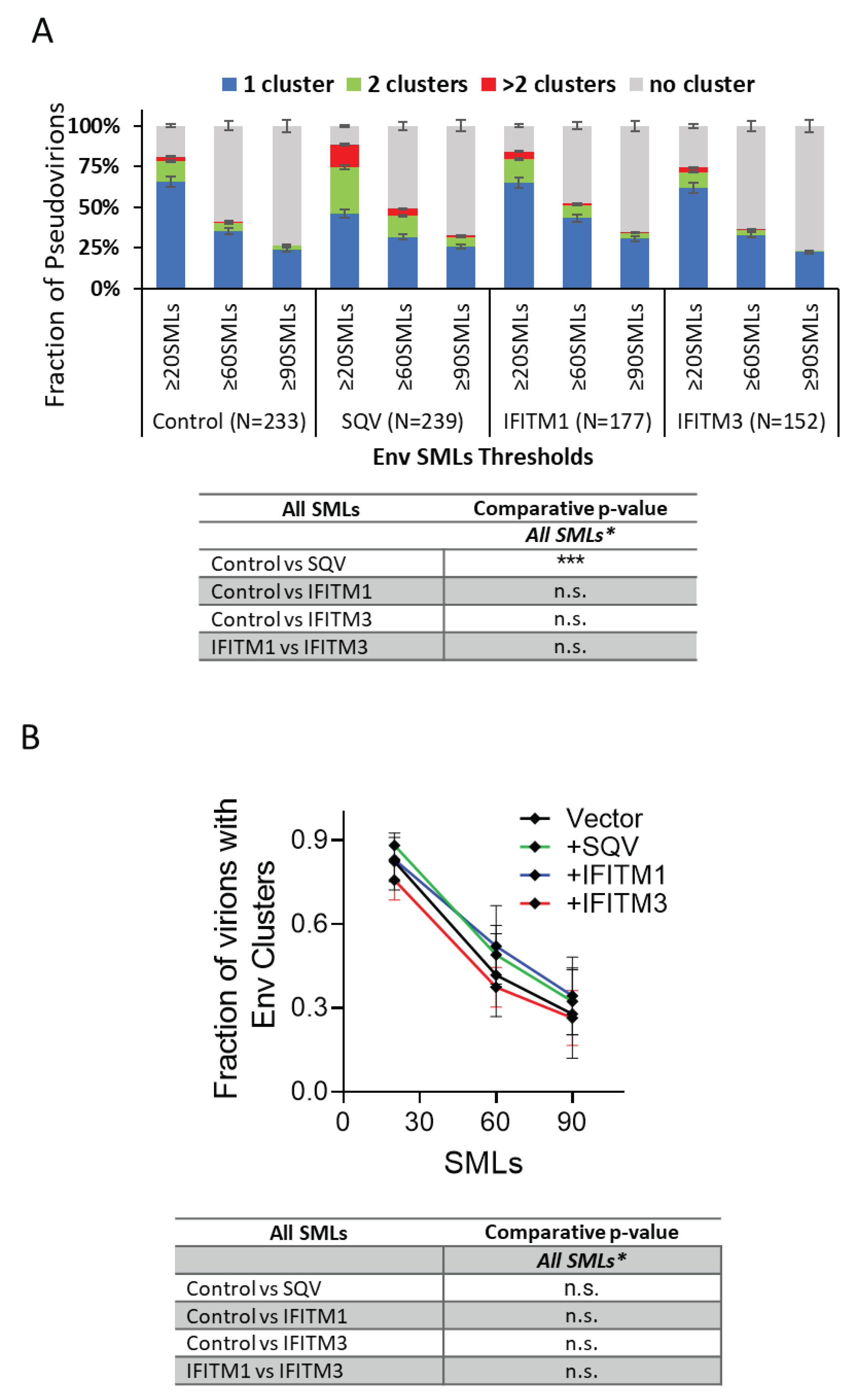

To determine whether IFITMs have significant effects on Env clustering across independent virus preparations, we analyzed the pooled results of all three viral panels. The four (

Figure 4A) and two-category (

Figure 4B) analyses of pseudoviruses show no difference in Env clustering in the presence of IFITM1 or IFITM3.

Thus, IFITM incorporation does not appear to disrupt Env clustering on mature pseudoviruses.

4. Discussion

Our dSTORM data support the HIV-1 maturation-driven coalescence of multiple Env clusters into largely a single focus per virion reported previously [

39,

47,

51]. A larger fraction of SQV-pretreated immature particles contained multiple Env clusters compared to control pseudoviruses (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). In contrast, analysis of independent virus panels revealed that incorporation of IFITMs does not significantly alter Env clustering. Of note, while not reaching statistical significance, IFITM1 and IFITM3 tended to exert opposite effects on the Env distribution on pseudoviruses. A smaller fraction of IFITM3 pseudoviruses contained Env clusters for some SML thresholds, while IFITM1 incorporation appeared to slightly promote clustering relative to control viruses (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). The apparent difference in effects of IFITM1 and IFITM3 Env clustering may be explained by fewer SMLs associated with IFITM3 particles compared to control and IFITM1 pseudoviruses. The lower localization density should diminish the apparent Env clustering, as defined by DBSCAN analysis. It is thus possible that, like IFITM1, IFITM3 may also slightly promotes Env clustering.

It is generally assumed that all three IFITMs act through similar complex mechanisms and that the spectrum of affected viruses is generally determined by the IFITMs’ subcellular localization. However, our results support the notion that IFITM1 and IFITM3 inhibit the fusion activity of progeny virions via distinct mechanisms. In agreement with the previous report [

21], we find that expression of IFITM3, but not IFITM1, in virus-producing cells inhibits both Env processing and incorporation into progeny pseudoviruses. Since IFITM1 does not significantly alter Env processing, incorporation into pseudoviruses or Env clustering, this protein may restrict HIV-1 by modulating the properties of the viral membrane and/or directly interfering with the Env function. Whereas IFITM3 can also disfavor viral fusion by similar mechanisms, it specifically inhibits Env processing and virus incorporation. The latter effects of IFITM3 upstream of virus budding may be responsible for the more potent inhibition of HIV-1 infectivity by this protein compared to IFITM1 (

Figure 1A).

Recent results showing the ability of the IFITM’s amphipathic helix and the conserved intracellular loop to directly bind cholesterol [

65,

66] are in line with the disruption of cholesterol-rich lipid domains. Future studies will be aimed at elucidating the effects of IFITMs on the properties of viral lipid membranes and how these changes modulate the ability of Env glycoproteins to mediate virus-cell fusion.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Immunoblotting and immunofluorescence analysis of two independent pseudovirus panels; Figure S2: Single-molecule localization analysis of Env incorporation pseudovirions after optimal binning of SML data; Figure S3: The effect of IFITMs on Env clustering on HIV-1 pseudoviruses imaged by dSTORM using 2-category analysis; Figure S4: Env-Env pairwise distance distribution analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.V., Y.-C.C., M.M. and G.B.M.; methodology, Y.-C.C., S.V. and M.M.; software, Y.-C.C.; validation, S.V., Y.-C.C. and G.B.M.; formal analysis, S.V., Y.-C.C. and S.E.G.; investigation, S.V., Y.-C.C. and M.M.; resources, G.B.M.; data curation, S.V.; writing—original draft preparation, S.V. and G.B.M.; writing—review and editing, S.V., Y.-C.C., M.M. and G.B.M.; visualization, S.V. and Y.-C.C.; supervision, M.M. and G.B.M.; project administration, G.B.M.; funding acquisition, G.B.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by This work was supported by the NIH R37 AI150453 and R01 AI135806 grants to G.B.M.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All pertinent data is included in the manuscript or available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Gokul Raghunath and David Prikryl for reading the manuscript and stimulating discussions. We also thank the NIH AIDS Research & Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, for the antibodies and reagents, and the Emory Pediatrics Bioinformatics Core for help with statistical analyses.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Siegrist, F.; Ebeling, M.; Certa, U. The small interferon-induced transmembrane genes and proteins. J Interferon Cytokine Res 2011, 31, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perreira, J.M.; Chin, C.R.; Feeley, E.M.; Brass, A.L. IFITMs restrict the replication of multiple pathogenic viruses. J Mol Biol 2013, 425, 4937–4955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, C.C.; Zhong, G.; Huang, I.C.; Farzan, M. IFITM-Family Proteins: The Cell’s First Line of Antiviral Defense. Annual review of virology 2014, 1, 261–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, G.; Schwartz, O.; Compton, A.A. More than meets the I: the diverse antiviral and cellular functions of interferon-induced transmembrane proteins. Retrovirology 2017, 14, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marziali, F.; Cimarelli, A. Membrane Interference Against HIV-1 by Intrinsic Antiviral Factors: The Case of IFITMs. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majdoul, S.; Compton, A.A. Lessons in self-defence: inhibition of virus entry by intrinsic immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2022, 22, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamond, M.S.; Farzan, M. The broad-spectrum antiviral functions of IFIT and IFITM proteins. Nat Rev Immunol 2013, 13, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlova, N.; Zavadil Kokas, F.; Hupp, T.R.; Vojtesek, B.; Nekulova, M. IFITM protein regulation and functions: Far beyond the fight against viruses. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 1042368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Herranz, M.; Taylor, J.; Sloan, R.D. IFITM proteins: Understanding their diverse roles in viral infection, cancer, and immunity. J Biol Chem 2023, 299, 102741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Pan, Q.; Rong, L.; He, W.; Liu, S.L.; Liang, C. The IFITM proteins inhibit HIV-1 infection. J Virol 2011, 85, 2126–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, A.A.; Bruel, T.; Porrot, F.; Mallet, A.; Sachse, M.; Euvrard, M.; Liang, C.; Casartelli, N.; Schwartz, O. IFITM proteins incorporated into HIV-1 virions impair viral fusion and spread. Cell host & microbe 2014, 16, 736–747. [Google Scholar]

- Tartour, K.; Appourchaux, R.; Gaillard, J.; Nguyen, X.N.; Durand, S.; Turpin, J.; Beaumont, E.; Roch, E.; Berger, G.; Mahieux, R.; et al. IFITM proteins are incorporated onto HIV-1 virion particles and negatively imprint their infectivity. Retrovirology 2014, 11, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, I.C.; Bailey, C.C.; Weyer, J.L.; Radoshitzky, S.R.; Becker, M.M.; Chiang, J.J.; Brass, A.L.; Ahmed, A.A.; Chi, X.; Dong, L.; et al. Distinct patterns of IFITM-mediated restriction of filoviruses, SARS coronavirus, and influenza A virus. PLoS Pathog 2011, 7, e1001258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, C.C.; Huang, I.C.; Kam, C.; Farzan, M. Ifitm3 limits the severity of acute influenza in mice. PLoS Pathog 2012, 8, e1002909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, D.; Weidner, J.M.; Qing, M.; Pan, X.B.; Guo, H.; Xu, C.; Zhang, X.; Birk, A.; Chang, J.; Shi, P.Y.; et al. Identification of five interferon-induced cellular proteins that inhibit west nile virus and dengue virus infections. J Virol 2010, 84, 8332–8341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Weston, S.; Kellam, P.; Marsh, M. IFITM proteins-cellular inhibitors of viral entry. Curr Opin Virol 2014, 4, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, Y.; Helenius, A. Virus entry at a glance. J Cell Sci 2013, 126 Pt 6, 1289–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini-Bavil-Olyaee, S.; Choi, Y.J.; Lee, J.H.; Shi, M.; Huang, I.C.; Farzan, M.; Jung, J.U. The antiviral effector IFITM3 disrupts intracellular cholesterol homeostasis to block viral entry. Cell host & microbe 2013, 13, 452–464. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Markosyan, R.M.; Zheng, Y.M.; Golfetto, O.; Bungart, B.; Li, M.; Ding, S.; He, Y.; Liang, C.; Lee, J.C.; et al. IFITM proteins restrict viral membrane hemifusion. PLoS Pathog 2013, 9, e1003124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, T.M.; Marin, M.; Chin, C.R.; Savidis, G.; Brass, A.L.; Melikyan, G.B. IFITM3 restricts influenza A virus entry by blocking the formation of fusion pores following virus-endosome hemifusion. PLoS Pathog 2014, 10, e1004048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Li, M.; Wilkins, J.; Ding, S.; Swartz, T.H.; Esposito, A.M.; Zheng, Y.M.; Freed, E.O.; Liang, C.; Chen, B.K.; et al. IFITM Proteins Restrict HIV-1 Infection by Antagonizing the Envelope Glycoprotein. Cell Rep 2015, 13, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhnl, A.; Musiol, A.; Heitzig, N.; Johnson, D.E.; Ehrhardt, C.; Grewal, T.; Gerke, V.; Ludwig, S.; Rescher, U. Late Endosomal/Lysosomal Cholesterol Accumulation Is a Host Cell-Protective Mechanism Inhibiting Endosomal Escape of Influenza A Virus. mBio 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appourchaux, R.; Delpeuch, M.; Zhong, L.; Burlaud-Gaillard, J.; Tartour, K.; Savidis, G.; Brass, A.; Etienne, L.; Roingeard, P.; Cimarelli, A. Functional Mapping of Regions Involved in the Negative Imprinting of Virion Particle Infectivity and in Target Cell Protection by Interferon-Induced Transmembrane Protein 3 against HIV-1. J Virol 2019, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suddala, K.C.; Lee, C.C.; Meraner, P.; Marin, M.; Markosyan, R.M.; Desai, T.M.; Cohen, F.S.; Brass, A.L.; Melikyan, G.B. Interferon-induced transmembrane protein 3 blocks fusion of sensitive but not resistant viruses by partitioning into virus-carrying endosomes. PLoS Pathog 2019, 15, e1007532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Steinkuhler, J.; Marin, M.; Li, X.; Lu, W.; Dimova, R.; Melikyan, G.B. Interferon-Induced Transmembrane Protein 3 Blocks Fusion of Diverse Enveloped Viruses by Altering Mechanical Properties of Cell Membranes. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 8155–8170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Du, S.; Tian, M.; Wang, Y.; Bai, J.; Tan, P.; Liu, W.; Yin, R.; Wang, M.; Jiang, Y.; et al. The Host Restriction Factor Interferon-Inducible Transmembrane Protein 3 Inhibits Vaccinia Virus Infection. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brass, A.L.; Huang, I.C.; Benita, Y.; John, S.P.; Krishnan, M.N.; Feeley, E.M.; Ryan, B.J.; Weyer, J.L.; van der Weyden, L.; Fikrig, E.; et al. The IFITM proteins mediate cellular resistance to influenza A H1N1 virus, West Nile virus, and dengue virus. Cell 2009, 139, 1243–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, C.J.; Griffin, L.M.; Little, A.S.; Huang, I.C.; Farzan, M.; Pyeon, D. The antiviral restriction factors IFITM1, 2 and 3 do not inhibit infection of human papillomavirus, cytomegalovirus and adenovirus. PloS one 2014, 9, e96579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa-Sasaki, K.; Murata, T.; Sasaki, J. IFITM1 enhances nonenveloped viral RNA replication by facilitating cholesterol transport to the Golgi. PLoS Pathog 2023, 19, e1011383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Guo, F.; Liu, F.; Cuconati, A.; Chang, J.; Block, T.M.; Guo, J.T. Interferon induction of IFITM proteins promotes infection by human coronavirus OC43. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2014, 111, 6756–6761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prelli Bozzo, C.; Nchioua, R.; Volcic, M.; Koepke, L.; Kruger, J.; Schutz, D.; Heller, S.; Sturzel, C.M.; Kmiec, D.; Conzelmann, C.; et al. IFITM proteins promote SARS-CoV-2 infection and are targets for virus inhibition in vitro. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tartour, K.; Nguyen, X.N.; Appourchaux, R.; Assil, S.; Barateau, V.; Bloyet, L.M.; Burlaud Gaillard, J.; Confort, M.P.; Escudero-Perez, B.; Gruffat, H.; et al. Interference with the production of infectious viral particles and bimodal inhibition of replication are broadly conserved antiviral properties of IFITMs. PLoS Pathog 2017, 13, e1006610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Li, M.; Wilkins, J.; Ding, S.; Swartz, T.H.; Esposito, A.M.; Zheng, Y.M.; Freed, E.O.; Liang, C.; Chen, B.K.; et al. IFITM Proteins Restrict HIV-1 Infection by Antagonizing the Envelope Glycoprotein. Cell reports 2015, 13, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Pan, Q.; Ding, S.; Wang, Z.; Yu, J.; Finzi, A.; Liu, S.L.; Liang, C. The V3 Loop of HIV-1 Env Determines Viral Susceptibility to IFITM3 Impairment of Viral Infectivity. J Virol 2017, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahi, Y.S.; Yimer, D.; Shi, G.; Majdoul, S.; Rahman, K.; Rein, A.; Compton, A.A. IFITM3 Reduces Retroviral Envelope Abundance and Function and Is Counteracted by glycoGag. mBio 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drouin, A.; Migraine, J.; Durand, M.A.; Moreau, A.; Burlaud-Gaillard, J.; Beretta, M.; Roingeard, P.; Bouvin-Pley, M.; Braibant, M. Escape of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein from the restriction of infection by IFITM3. J Virol 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beitari, S.; Pan, Q.; Finzi, A.; Liang, C. Differential Pressures of SERINC5 and IFITM3 on HIV-1 Envelope Glycoprotein over the Course of HIV-1 Infection. J Virol 2020, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sood, C.; Marin, M.; Chande, A.; Pizzato, M.; Melikyan, G.B. SERINC5 protein inhibits HIV-1 fusion pore formation by promoting functional inactivation of envelope glycoproteins. J Biol Chem 2017, 292, 6014–6026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.C.; Sood, C.; Marin, M.; Aaron, J.; Gratton, E.; Salaita, K.; Melikyan, G.B. Super-Resolution Fluorescence Imaging Reveals That Serine Incorporator Protein 5 Inhibits Human Immunodeficiency Virus Fusion by Disrupting Envelope Glycoprotein Clusters. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 10929–10943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Le Duff, Y.; Wang, Y.; Pan, Q.; Ding, S.; Zheng, Y.M.; Liu, S.L.; Liang, C. Primate lentiviruses are differentially inhibited by interferon-induced transmembrane proteins. Virology 2015, 474, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, J.; Zheng, Y.M.; Yu, J.; Liang, C.; Liu, S.L. Nonhuman Primate IFITM Proteins Are Potent Inhibitors of HIV and SIV. PloS one 2016, 11, e0156739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, T.L.; Wilson, H.; Iyer, S.S.; Coss, K.; Doores, K.; Smith, S.; Kellam, P.; Finzi, A.; Borrow, P.; Hahn, B.H.; et al. Resistance of Transmitted Founder HIV-1 to IFITM-Mediated Restriction. Cell host & microbe 2016, 20, 429–442. [Google Scholar]

- Drouin, A.; Migraine, J.; Durand, M.A.; Moreau, A.; Burlaud-Gaillard, J.; Beretta, M.; Roingeard, P.; Bouvin-Pley, M.; Braibant, M. Escape of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein from the restriction of infection by IFITM3. J Virol 2021, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, P.; Chertova, E.; Bess, J., Jr.; Lifson, J.D.; Arthur, L.O.; Liu, J.; Taylor, K.A.; Roux, K.H. Electron tomography analysis of envelope glycoprotein trimers on HIV and simian immunodeficiency virus virions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003, 100, 15812–15817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, P.; Liu, J.; Bess, J., Jr.; Chertova, E.; Lifson, J.D.; Grise, H.; Ofek, G.A.; Taylor, K.A.; Roux, K.H. Distribution and three-dimensional structure of AIDS virus envelope spikes. Nature 2006, 441, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, P.; Winkler, H.; Chertova, E.; Taylor, K.A.; Roux, K.H. Cryoelectron tomography of HIV-1 envelope spikes: further evidence for tripod-like legs. PLoS Pathog 2008, 4, e1000203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnacki, J.; Waithe, D.; Carravilla, P.; Huarte, N.; Galiani, S.; Enderlein, J.; Eggeling, C. Envelope glycoprotein mobility on HIV-1 particles depends on the virus maturation state. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, P.; DeVico, A.L.; Foulke, J.S.; Lewis, G.K.; Pazgier, M.; Ray, K. Stoichiometric Analyses of Soluble CD4 to Native-like HIV-1 Envelope by Single-Molecule Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Cell Rep 2019, 29, 176–186.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenberg, O.F.; Magnus, C.; Rusert, P.; Regoes, R.R.; Trkola, A. Different infectivity of HIV-1 strains is linked to number of envelope trimers required for entry. PLoS Pathog 2015, 11, e1004595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnus, C.; Regoes, R.R. Estimating the stoichiometry of HIV neutralization. PLoS Comput Biol 2010, 6, e1000713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnacki, J.; Staudt, T.; Glass, B.; Bingen, P.; Engelhardt, J.; Anders, M.; Schneider, J.; Muller, B.; Hell, S.W.; Krausslich, H.G. Maturation-dependent HIV-1 surface protein redistribution revealed by fluorescence nanoscopy. Science 2012, 338, 524–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, N.H.; Chan, J.; Lambele, M.; Thali, M. Clustering and mobility of HIV-1 Env at viral assembly sites predict its propensity to induce cell-cell fusion. J Virol 2013, 87, 7516–7525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, J.; Li, M.; Yang, H.; Zhang, C. Evolutionary dynamics of the interferon-induced transmembrane gene family in vertebrates. PLoS One 2012, 7, e49265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Decker, J.M.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Arani, R.B.; Kilby, J.M.; Saag, M.S.; Wu, X.; Shaw, G.M.; Kappes, J.C. Emergence of resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in patients receiving fusion inhibitor (T-20) monotherapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2002, 46, 1896–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenna, P.M.; Pomerantz, R.J.; Dietzschold, B.; McGettigan, J.P.; Schnell, M.J. Covalently linked human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120/gp41 is stably anchored in rhabdovirus particles and exposes critical neutralizing epitopes. J Virol 2003, 77, 12782–12794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammonds, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Lee, F.; Spearman, P. Advances in methods for the production, purification, and characterization of HIV-1 Gag-Env pseudovirion vaccines. Vaccine 2007, 25, 8036–8048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikon N-STORM protocol-sample preparation. Available online: http://www.mvi-inc.com/wp-content/uploads/N-STORM+Protocol.pdf.

- Heris, M.K. DBSCAN Clustering in MATLAB. Available online: https://yarpiz.com/255/ypml110-dbscan-clustering.

- Izenman, A.J. Recent Developments in Nonparametric Density Estimation. (413).

- Ester, M.; Kriegel, H.-P.; Sander, J.; Xu, X. In A Density-Based Algorithm for Discovering Clusters in Large Spatial Databases with Noise, Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 1996; 1996.

- Xu, X.; Ester, M.; Kriegel, H.-P.; Sander, J. A distribution-based clustering algorithm for mining in large spatial databases. Proceedings 14th International Conference on Data Engineering 1998, 324–331. [Google Scholar]

- Smithson, M.; Verkuilen, J. A better lemon squeezer? Maximum-likelihood regression with beta-distributed dependent variables. Psychol Methods 2006, 11, 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montefiori, D.C. Evaluating neutralizing antibodies against HIV, SIV, and SHIV in luciferase reporter gene assays. Curr Protoc Immunol 2005, Chapter 12, 12 11 1-12 11 17.

- Platt, E.J.; Wehrly, K.; Kuhmann, S.E.; Chesebro, B.; Kabat, D. Effects of CCR5 and CD4 cell surface concentrations on infections by macrophagetropic isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol 1998, 72, 2855–2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, K.; Datta, S.A.K.; Beaven, A.H.; Jolley, A.A.; Sodt, A.J.; Compton, A.A. Cholesterol Binds the Amphipathic Helix of IFITM3 and Regulates Antiviral Activity. J Mol Biol 2022, 434, 167759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, T.; Yang, X.; Lee, H.; Garst, E.H.; Valencia, E.; Chandran, K.; Im, W.; Hang, H.C. S-Palmitoylation and Sterol Interactions Mediate Antiviral Specificity of IFITMs. ACS chemical biology 2022, 17, 2109–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).