Submitted:

13 September 2023

Posted:

14 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Sample Characterization

2.1.1. Morbidity and Mortality

2.1.2. Tumor recurrence

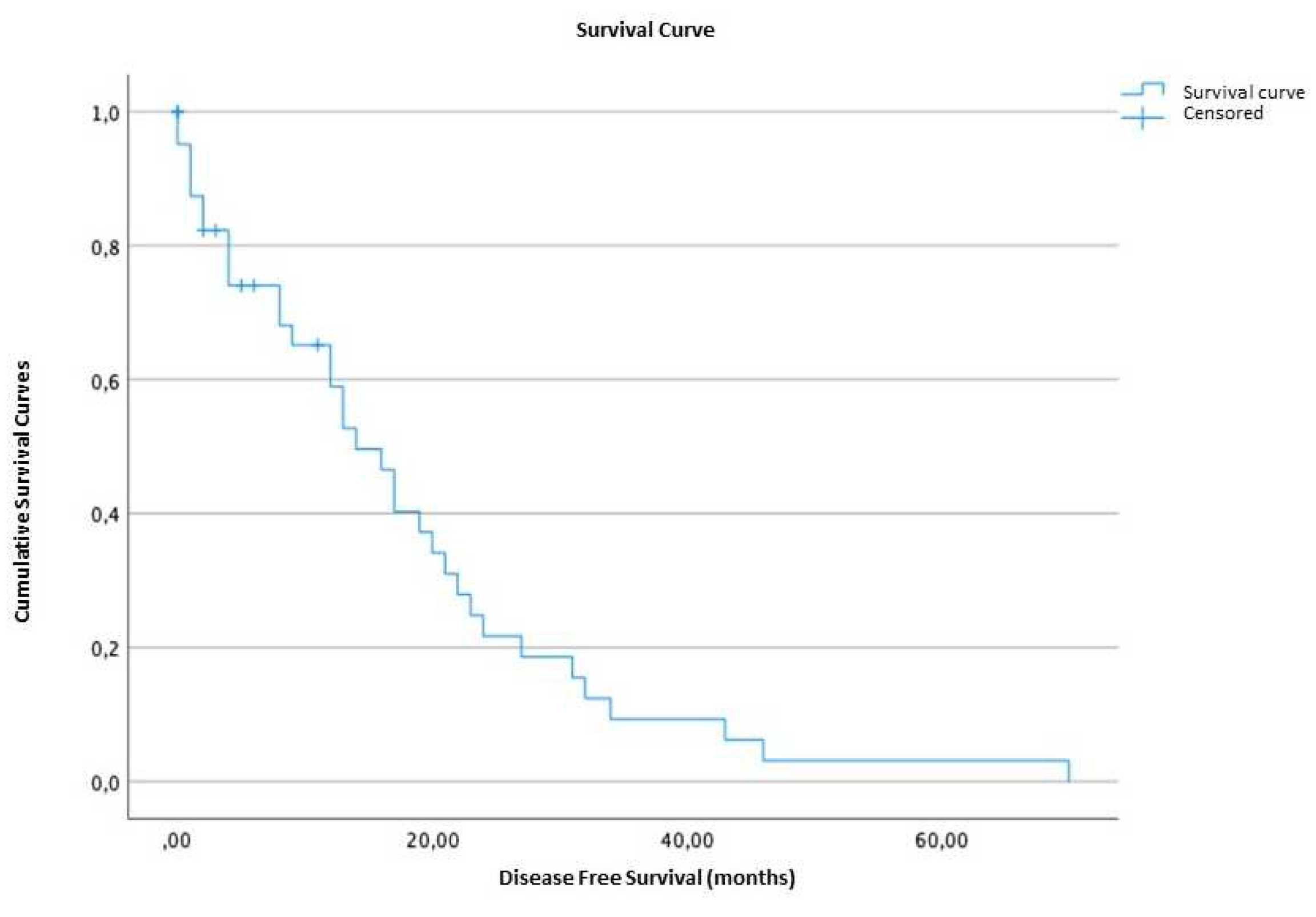

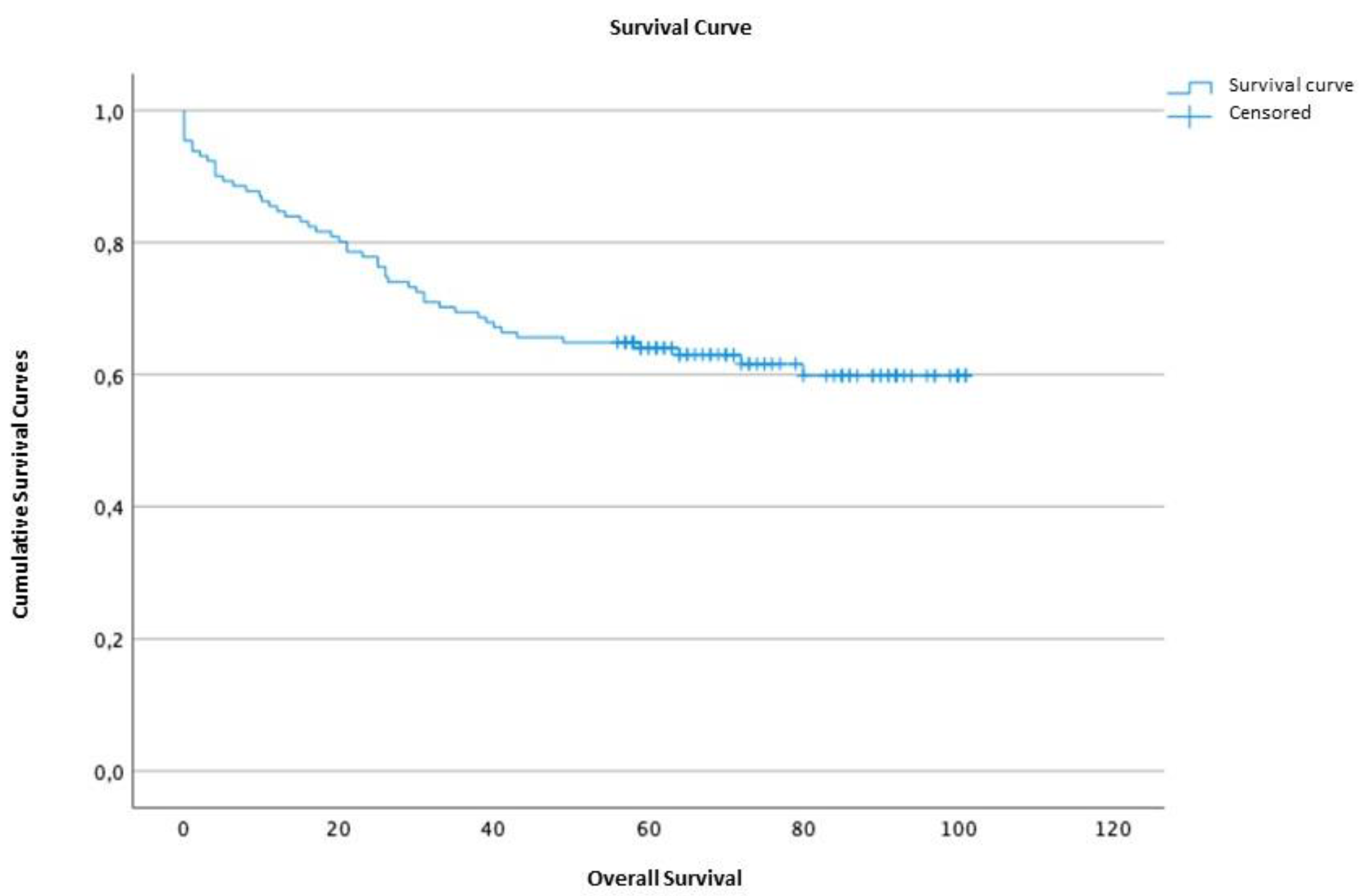

2.1.3. Survival time and disease-free survival

2.2. Results of the application of the scales

2.2.1. POSSUM

2.2.2. P-POSSUM

2.2.3. O-POSSUM

2.3. Assessment of surgical risk scales

2.3.1. Comparison of results obtained from the scales regarding postoperative outcome

Morbidity

2.3.2. Calibration

Mortality

Morbidity

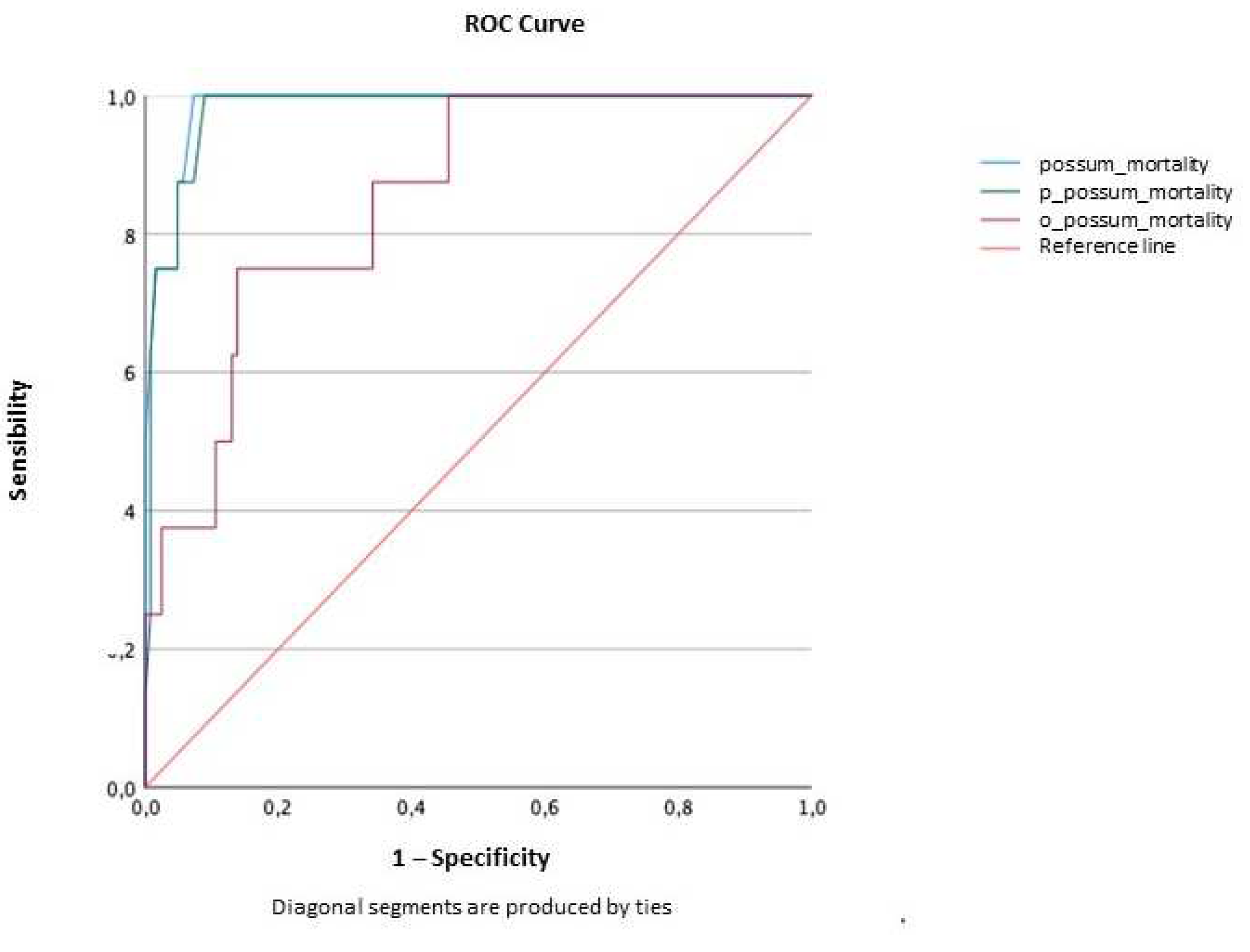

2.3.3. Discrimination

Mortality

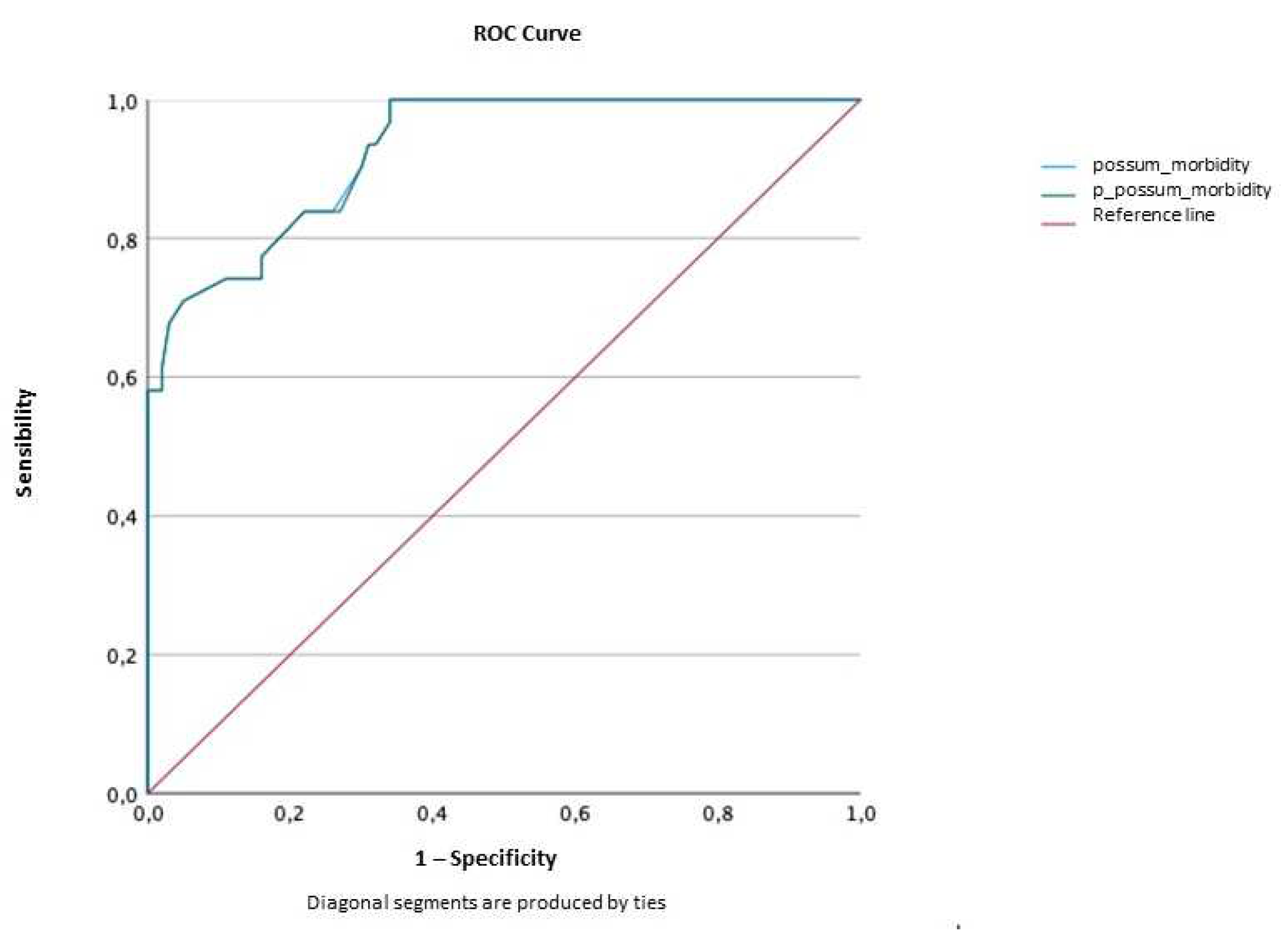

Morbidity

2.4. Correlation among possum, p-possum and o-possum scales

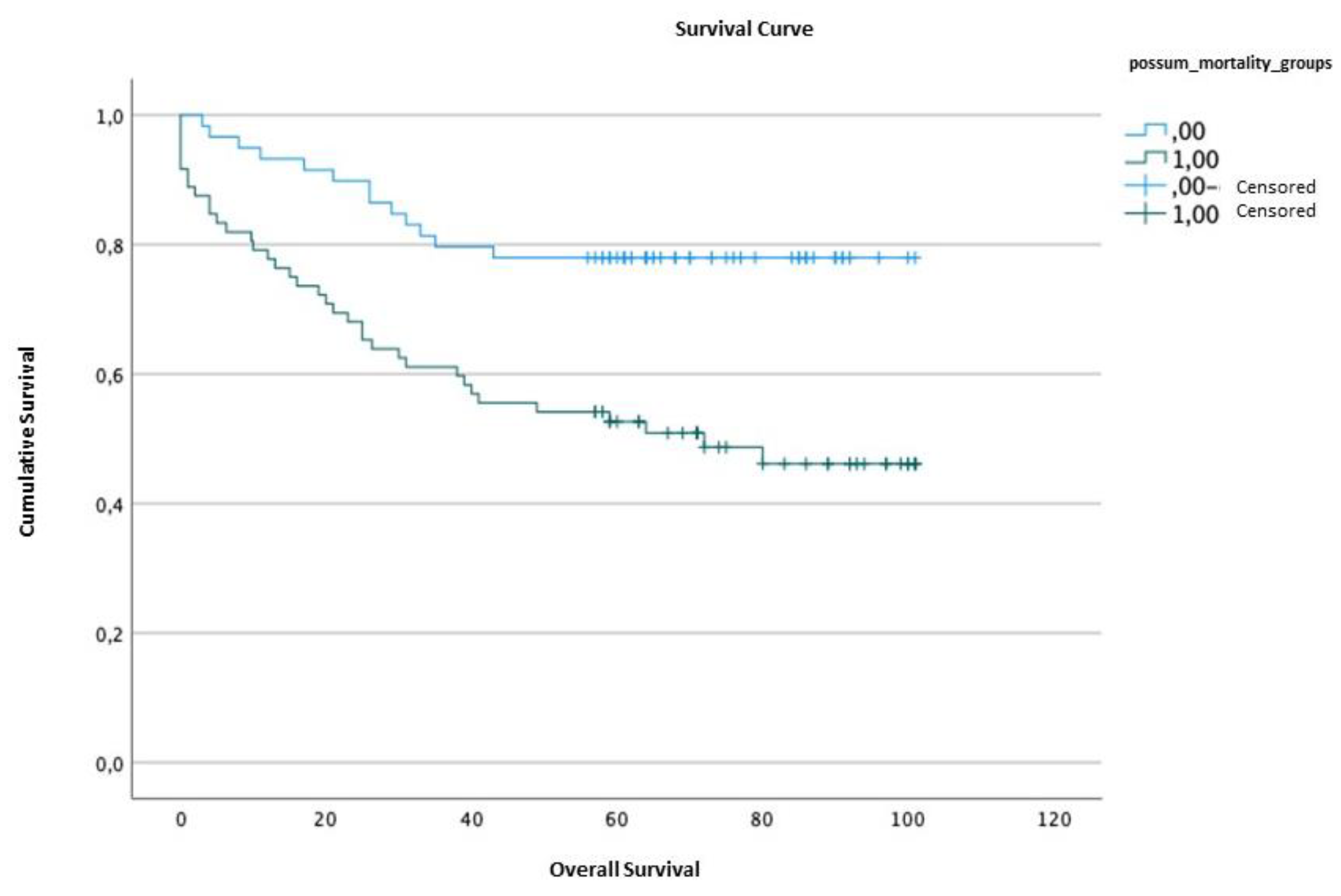

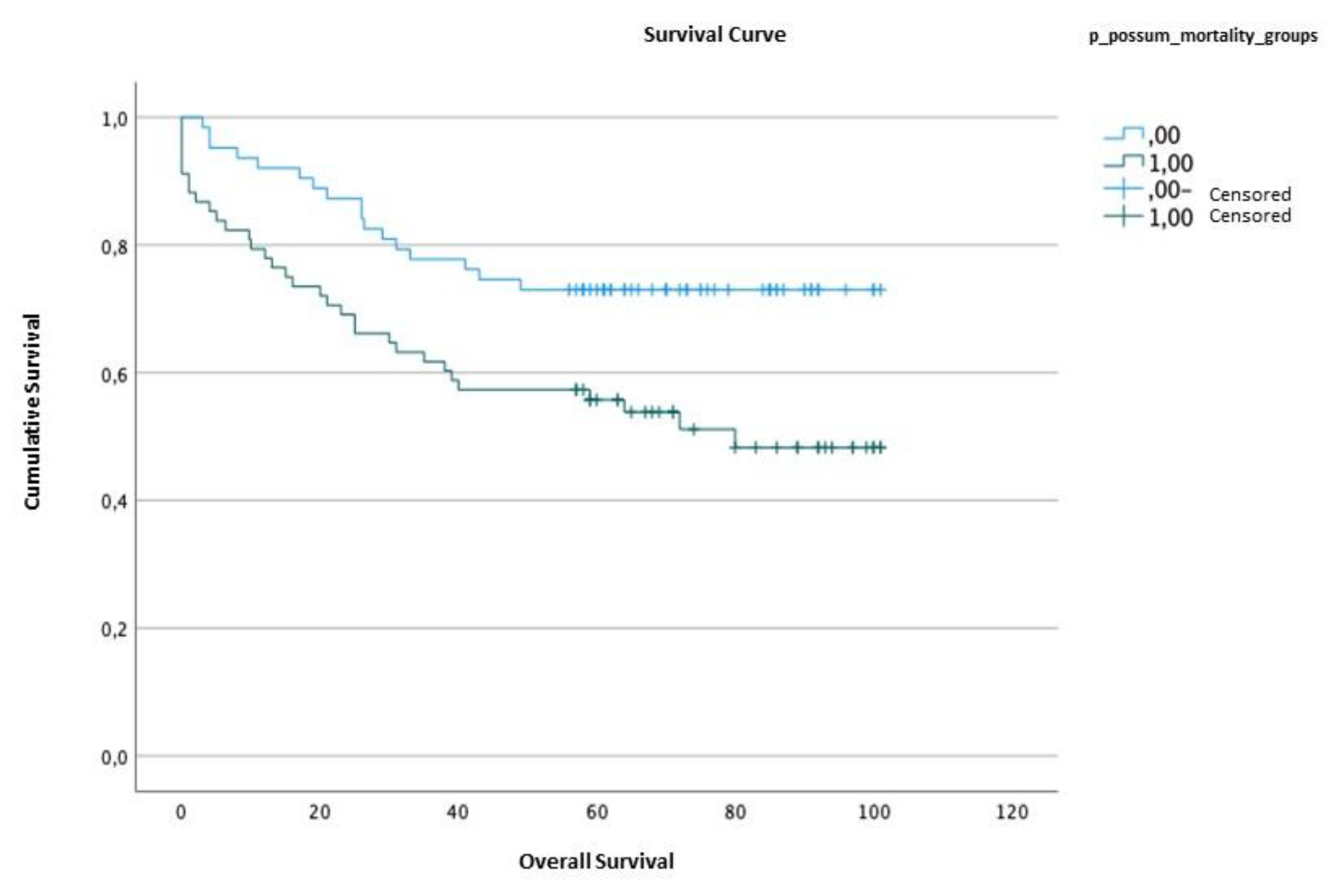

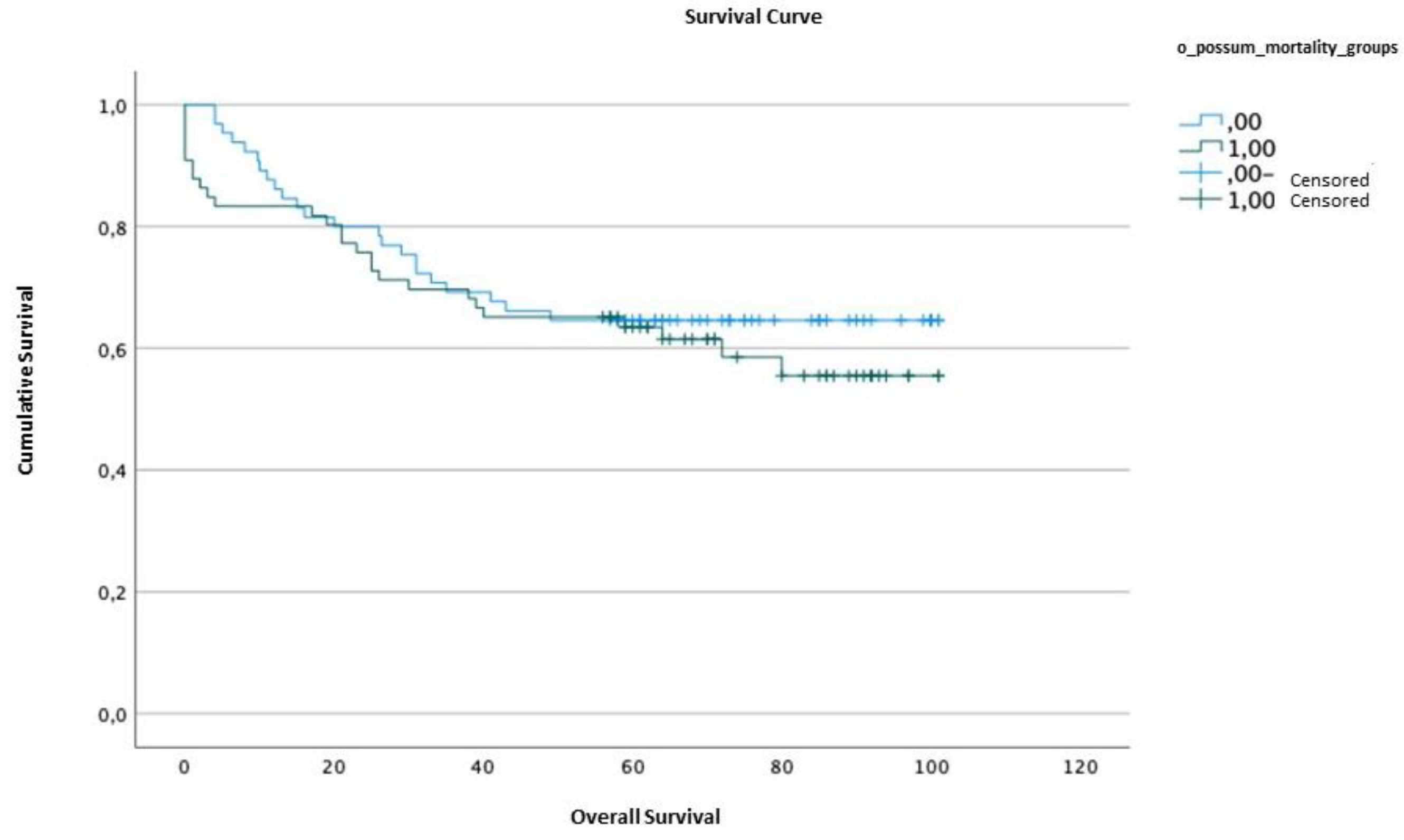

2.5. Survival analysis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. [CrossRef]

- DGS. PORTUGAL Doenças Oncologicas em Números - 2014. 2014;86. Available from: http://www.dgs.pt/estatisticas-de-saude/estatisticas-de-saude/publicacoes/portugal-doencas-oncologicas-em-numeros-2014.asp.

- Aavv. Avaliação da performance cirúrgica pelo P-POSSUM em doentes com cancro gástrico - revisão de 5 anos. Rev Port Cardiol. 2006;7:104 ST-Revista Portuguesa de Psicanálise.

- Okines A, Verheij M, Allum W, Cunningham D, Cervantes A. Gastric cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol [Internet]. 2010;21(SUPPL. 5):v50–4. [CrossRef]

- Pan QX, Su ZJ, Zhang JH, Wang CR, Ke SY. A comparison of the prognostic value of preoperative inflammation-based scores and TNM stage in patients with gastric cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:1375–85.

- Kanda M. Preoperative predictors of postoperative complications after gastric cancer resection. Surg Today [Internet]. 2020;50(1):3–11. [CrossRef]

- Nagabhushan JS, Srinath S, Weir F, Angerson WJ, Sugden BA, Morran CG. Comparison of P-POSSUM and O-POSSUM in predicting mortality after oesophagogastric resections. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83(979):355–8. [CrossRef]

- Hong S, Wang S, Xu G, Liu JL. Evaluation of the POSSUM, p-POSSUM, o-POSSUM, and APACHE II scoring systems in predicting postoperative mortality and morbidity in gastric cancer patients. Asian J Surg [Internet]. 2017;40(2):89–94. [CrossRef]

- Tekkis PP, McCulloch P, Poloniecki JD, Prytherch DR, Kessaris N, Steger AC. Risk-adjusted prediction of operative mortality in oesophagogastric surgery with O-POSSUM. Br J Surg. 2004;91(3):288–95. [CrossRef]

- Luna A, Rebasa P, Navarro S, Montmany S, Coroleu D, Cabrol J, et al. An evaluation of morbidity and mortality in oncologic gastric surgery with the application of POSSUM, P-POSSUM, and O-POSSUM. World J Surg. 2009;33(9):1889–94. [CrossRef]

- Powell C, Trickey R, Morgan C. Audit of Patients Receiving Palliative Chemotherapy for Oesophago-gastric Cancer at Velindre Cancer Centre in 2012. Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2014;26:S2. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.clon.2014.04.00. [CrossRef]

- Scott S, Lund JN, Gold S, Elliott R, Vater M, Chakrabarty MP, et al. An evaluation of POSSUM and P-POSSUM scoring in predicting post-operative mortality in a level 1 critical care setting. BMC Anesthesiol. 2014;14(1):1–7. [CrossRef]

- KISA NG, KISA E, Cevik BE. Prediction of Mortality in Patients After Oncologic Gastrointestinal Surgery: Comparison of the ASA, APACHE II, and POSSUM Scoring Systems. Cureus. 2021;13(3). [CrossRef]

- Vather R, Zargar-Shoshtari K, Adegbola S, Hill AG. Comparison of the possum, P-POSSUM and Cr-POSSUM scoring systems as predictors of postoperative mortality in patients undergoing major colorectal surgery. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76(9):812–6. [CrossRef]

- Tez M, Yoldaş Ö, Gocmen E, Külah B, Koc M. Evaluation of P-POSSUM and CR-POSSUM scores in patients with colorectal cancer undergoing resection. World J Surg. 2006;30(12):2266–9. [CrossRef]

- Bollschweiler E, Lubke T, Monig SP, Holscher AH. Evaluation of POSSUM scoring system in patients with gastric cancer undergoing D2-gastrectomy. BMC Surg. 2005;5:1–7. [CrossRef]

- Lamb P, Sivashanmugam T, White M, Irving M, Wayman J, Raimes S. Gastric cancer surgery - A balance of risk and radically. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2008;90(3):235–42. [CrossRef]

- Sah BK, Min CM, Yan WX, Meng YQ, Chen L, Ming X, et al. Risk adjusted auditing of postop complications in gastric cancer patients by POSSUM. Int J Surg. 2008;6(4):311–6. [CrossRef]

- Goulart A, Martins S. Avaliação do risco cirúrgico nos doentes com cancro colo-rectal: POSSUM ou ACPGBI? Rev Port Cir [Internet]. 2013;2(24):1–12. Available from: https://repositorium.sdum.uminho.pt/bitstream/1822/33553/1/goulart a_revista portuguesa de cirurgia 2013.pd.

- Copeland GP, Jones D, Walters M. POSSUM: A scoring system for surgical audit. Br J Surg. 1991;78(3):355–60. [CrossRef]

- Blay-Domínguez E, Lajara-Marco F, Bernáldez-Silvetti PF, Veracruz-Gálvez EM, Muela-Pérez B, Palazón-Banegas MÁ, et al. O-POSSUM score predicts morbidity and mortality in patients undergoing hip fracture surgery. Rev Española Cirugía Ortopédica y Traumatol (English Ed [Internet]. 2018;62(3):207–15. [CrossRef]

| DATA | n (%) | |

| AGE(years) | <40 | 2 (1.5) |

| 40-49 | 12 (9.2) | |

| 50-59 | 34 (26) | |

| 60-69 | 20 (15.3) | |

| 70-79 | 44 (33.6) | |

| >80 | 19 (14.5) | |

| GENDER | Male | 74 (56.5) |

| Female | 57 (43.5) | |

| TUMOR LOCATION | Antrum | 57 (43.5) |

| Body | 39 (29.8) | |

| Body and Antrum | 3 (2.3) | |

| Cardia | 2 (1.5) | |

| Fundus | 1 (0.8) | |

| HISTOLOGICAL TYPE | Intestinal Type | 80 (61.1) |

| Diffuse Type | 27 (20.6) | |

| Mixed Type | 21 (16) | |

| Unclassified | 3 (2.3) | |

| STAGING | In situ | 3 (2.3) |

| I | 60 (45.8) | |

| II | 33 (25.2) | |

| III | 35 (26.7) | |

| SURGICAL TYPE | TG | 65 (49.6) |

| STG | 66 (50.4) |

| LOCAL COMPLICATIONS | n | |||

| Anastomotic leak | 11 | |||

| Fistula | 2 | |||

| Surgical wound infection | 2 | |||

| SYSTEMIC COMPLICATIONS | ||||

| PULMONARY | Respiratory infection | 7 | ||

| Pleural effusion | 2 | |||

| Atelectasis | 1 | |||

| Pneumotorax | 1 | |||

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 | |||

| CARDIAC | Atrial fibrillation | 1 | ||

| SEPTIC | Sepsis | 5 | ||

| HEMORRHAGIC | Hypovolemic shock | 1 | ||

| ABDOMINAL | Intestinal obstruction | 2 | ||

| Paralytic ileus | 2 | |||

| Peritonitis | 1 | |||

| Mortality (%) | No mortality (%) | p value | U | r | |

| POSSUM | 14.81±4.73 | 4.19±3.35 | <0.001 | 968.00 | 0.398 |

| P-POSSUM | 6.33±3.14 | 1.15±1.23 | <0.001 | 963.00 | 0.396 |

| O-POSSUM | 21.32±19.46 | 9.62±9.42 | 0.001 | 837.00 | 0.290 |

| Morbidity(%) | No morbidity (%) | p value | U | r | |

| POSSUM | 45.02±24.73 | 21.08±15.97 | <0.001 | 2873.50 | 0.626 |

| P-POSSUM | 45.02±24.73 | 21.08±15.97 | <0.001 | 2873.50 | 0.626 |

| Qui-Squared | df | p value | |

| POSSUM | 1.02 | 8 | 0.998 |

| P-POSSUM | 1.04 | 7 | 0.994 |

| O-POSSUM | 6.692 | 8 | 0.570 |

| n | n with complications* | % Observed and expected morbidity at 30 days | |||

| Observed | POSSUM | P-POSSUM | |||

| Global | 131 | 31 | 23.66% | 18.32% (O:E 1.29) |

18.32% (O:E 1.29) |

| Stage I | 60 | 7 | 11.67% | 6.67% (O:E 1.75) |

6.67% (O:E 1.75) |

| Stage II | 33 | 12 | 36.36% | 30.30% (O:E 1.21) |

30.30% (O:E 1.21) |

| Stage III | 35 | 12 | 34.29% |

28.57% (O:E 1.2) |

28.57% (O:E 1.2) |

| Intestinal Type | 80 | 24 | 30.00% | 23.75% (O:E 1.26) |

23.75% (O:E 1.26) |

| Diffuse type | 27 | 5 | 18.51% | 14.80% (O:E 1.25) |

14.80% (O:E 1.25) |

| TG | 65 | 13 | 20.00% | 13.80% (O:E 1.45%) |

13.80% (O:E 1.45%) |

| STG | 66 | 18 | 27.27% |

22.72% (O:E 1.2) |

22.72% (O:E 1.2) |

| Qui-Squared | df | P value | |

| POSSUM | 11.484 | 8 | 0.176 |

| P-POSSUM | 11.484 | 8 | 0.176 |

| n | n with complications* | % Observed and expected morbidity at 30 days | |||

| Observed | POSSUM | P-POSSUM | |||

| Global | 131 | 31 | 23.66% | 18.32% (O:E 1.29) |

18.32% (O:E 1.29) |

| Stage I | 60 | 7 | 11.67% | 6.67% (O:E 1.75) |

6.67% (O:E 1.75) |

| Stage II | 33 | 12 | 36.36% | 30.30% (O:E 1.21) |

30.30% (O:E 1.21) |

| Stage III | 35 | 12 | 34.29% |

28.57% (O:E 1.2) |

28.57% (O:E 1.2) |

| Intestinal Type | 80 | 24 | 30.00% | 23.75% (O:E 1.26) |

23.75% (O:E 1.26) |

| Diffuse type | 27 | 5 | 18.51% | 14.80% (O:E 1.25) |

14.80% (O:E 1.25) |

| TG | 65 | 13 | 20.00% | 13.80% (O:E 1.45%) |

13.80% (O:E 1.45%) |

| STG | 66 | 18 | 27.27% |

22.72% (O:E 1.2) |

22.72% (O:E 1.2) |

| AUC | Confidence interval (95%) | p value | ||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||

| POSSUM | 0.984 | 0.962 | 1.000 | <0.001 |

| P-POSSUM | 0.979 | 0.953 | 1.000 | <0.001 |

| O-POSSUM | 0.851 | 0.736 | 0.966 | 0.001 |

| AUC | Confidence interval (95%) | p value | ||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||

| POSSUM | 0.927 | 0.880 | 0.974 | <0.001 |

| P-POSSUM | 0.927 | 0.879 | 0.974 | <0.001 |

| CORRELATIONAL VARIABLES | n | rs | p value | |

| POSSUM | P-POSSUM | 131 | 0.991 | <0.001 |

| POSSUM | O-POSSUM | 131 | 0.363 | <0.001 |

| P-POSSUM | O-POSSUM | 131 | 0.378 | <0.001 |

| Survival time | Standard error | Confidence interval (95%) | ||||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||||

| POSSUM | <4.19 | 83.61 | 4.23 | 75.14 | 92.08 | |

| ≥4.19 | 59.56 | 5.00 | 49.76 | 69.36 | ||

| P-POSSUM | <1.18 | 79.95 | 4.45 | 71.23 | 88.68 | |

| ≥1.18 | 61.38 | 5.17 | 51.24 | 71.51 | ||

| O-POSSUM | <10.25 | 72.62 | 4.86 | 63.10 | 82.14 | |

| ≥10.25 | 67.95 | 5.10 | 57.24 | 71.51 | ||

| Qui-Squared | df | p value | |

| POSSUM | 11.61 | 1 | 0.001 |

| P-POSSUM | 6.823 | 1 | 0.009 |

| O-POSSUM | 0.488 | 1 | 0.485 |

| SCALE | EQUATION | |

| Mortality | POSSUM | Ln R/1-R= -7,04 + (0,13x physiological score) + (0,16x operative score) |

| P-POSSUM | Ln R/1-R= -9,065 + (0,1692x physiological score) + (0,155x operative score) | |

| O-POSSUM | Ln R/1-R= -7,566 + (0,055 x age) + (0,080 x physiological score + B1 coefficient (tumoral staging) + B2 coefficient (surgery urgency) + B3 coefficient (type of surgery) * | |

| Morbidity | POSSUM /P-POSSUM** | Ln R/1-R= -5,91+ (0,16x physiological score) + (0,19x operative score). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).