1. Introduction

Workplace bullying is a serious problem that can adversely affect the physical and mental health of employees [

1]. It in-volves repetitive aggressive behaviors that target individuals or groups and cause physical or psychological harm. Types of bul-lying include abuse, exclusion, humiliation, intimidation, and verbal, physical, sexual, and cyberbullying. This can lead to de-creased job satisfaction and work performance and increased absenteeism and turnover rates [

2]. Despite the negative conse-quences of workplace bullying, it continues to be a prevalent is-sue in many organizations. An analysis of 148 organizations worldwide found that 49% showed evidence of workplace bully-ing, up to 13% of employees were bullied on the job, and up to 30% were bullied at any time during their careers [

3].

Given the widespread nature of workplace bullying and its impact on employees, numerous studies have demonstrated its association with an increased risk of depressive symptoms. For example, a study conducted in Germany found that workplace bullying, particularly when perpetrated by co-workers, was asso-ciated with an increased risk of depressive symptoms among employees [

4]. Similarly, a study conducted among Taiwanese nurses found that workplace bullying is positively associated with depression [

5]. Unlike workplace cultures in other countries, Korean workplace culture, which emphasizes interpersonal rela-tionships due to high levels of power distance, Confucianism, and collectivism in Korea's culture [

6], can make workplaces prone to bullying [

7]. In Korea, conflict with colleagues rather than supervisors emerged as a more potent predictor of work-place bullying, indicating the unique dynamics at play [

8]. Addi-tionally, unlike in the United Kingdom, factors such as job type and part-time employment status had little influence on bullying scores [

8]. Furthermore, stress from workplace bullying can spill over into the home lives of Korean employees, leading to greater work-to-family conflict [

7]. These unique cultural and social contexts can make the impact of workplace bullying particularly profound in Korean society. These peculiarities highlight the need for further research to better understand the unique char-acteristics of workplace bullying in Korean contexts, which are not yet well-explored.

Gender can influence the relationship between workplace bullying and depression, with research consistently showing a higher prevalence of depression in female employees compared to their male counterparts [

9]. These gender-specific differences extend to the risk factors contributing to workplace bullying, which can vary significantly between men and women [

10]. Pre-vious studies investigating the relationship between workplace bullying and depression have yielded inconsistent results when stratified by gender. For instance, one study found that work-place bullying negatively impacted mental health, but being male served as a protective factor, helping maintain mental health despite negative workplace experiences [

11]. Conversely, a lon-gitudinal study demonstrated that workplace bullying exclu-sively predicts mental health problems in males [

12]. Particularly in Korea, where gender roles are distinctly defined [

7], it is criti-cal to conduct gender-stratified research on workplace bullying and depression. However, to date, no such study has been con-ducted in the Republic of Korea. Therefore, it is crucial to exam-ine the relationship between workplace bullying and depression separately among Korean employees for each gender.

Existing research frequently overlooks the influence of gen-der differences in workplace bullying. When gender differences are considered, the validity of findings related to gender-specific experiences of workplace bullying can be questioned because of the relatively small number of subjects analyzed separately by gender or significant discrepancies in the number of male and female participants [

12]. For a more comprehensive under-standing of the relationship between workplace bullying and the prevalence of depression among Korean employees, this study included a large dataset of Korean employees from various in-dustries. In addition, this study will explore gender differences in this relationship, which has been identified as an important fac-tor in previous research [

11]. However, there is still an ongoing debate about the role of gender in the relationship between workplace bullying and depression. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

Workplace bullying may be positively associated with the prevalence of depression among Korean employees.

The relationship between workplace bullying and the prevalence of depression can be moderated by gender.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were male and female employees aged 19–65 years who underwent workplace mental health screening at the Workplace Mental Health Institute of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, Seoul, Republic of Korea, between April 2020 and March 2022. The participants were office or manufacturing facility employees at one of the country’s eighteen public institutions or large companies who voluntarily participated in mental health examinations upon invitation from their companies. Only participants who completed the questionnaires and provided sociodemographic information were included in the study. Thus, 12,344 participants (7,981 men and 4,363 women) were included in the analysis.

All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital and adhered to the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki and principles of Good Clinical Practice (approval number: KBSMC 2022-03-046). The requirement for informed consent was waived because only de-identified data routinely collected during health screening visits were used.

2.2. Clinical Assessments

Information on sociodemographic factors was collected, including age, gender, level of education (college graduate or below, university graduate, master’s degree or above), and marital status (married, unmarried, other [divorced, widowed, or separated]). Job-related demographic factors were also collected, including the duration of work in the current workplace (years), hours of work per week, and monthly earned income (below 3 million won, between 3 and 4 million won, and 4 million won or above).

Occupational stress was assessed using the Short Form of the Korean Occupational Stress Scale-Short Form (KOSS-SF), a 24-item self-report questionnaire scored on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = agree, and 4 = strongly agree). Higher scores indicate greater workplace stress. The score comprised seven work-related stress subscales: high job demands, insufficient job control, inadequate social support, job insecurity, organizational injustice, lack of rewards, and discomfort in the organizational climate. As the number of items constituting each subscale is different, the weight reflected depending on the type of stress on total stress may be different. To compensate for this problem, the following formula [

13] was used rather than calculating the severity of total stress by simply summing the subscale scores. Cronbach’s alpha for the KOSS-SF was 0.895.

Burnout was measured by the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI) [

14]

, which consists of 16 items. Eight items each measured the exhaustion and the disengagement dimensions. Both subscales include four positively and four negatively worded items, with responses scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Responses were re-scored such that high scores indicated high levels of burnout. Both the exhaustion (Cronbach’s α: 0.882) and the disengagement (Cronbach’s α: 0.833) subscales were reliable.

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Korean version of the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale [

15,

16]. It is a self-reported questionnaire with responses measured on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3 points; a higher total score indicates more severe depressive symptoms. Cronbach’s alpha for the Korean version of the CES-D was 0.765. Traditionally, a CES-D score of 16 or higher has been used as the cut-off for screening depression [

17]. Therefore, in this study, we defined cases with a CES-D score of 16 or higher as the presence of depression.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The baseline characteristics of the study groups were compared using independent t-tests for continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorical variables. The prevalence of depression in each group classified by the experience of workplace bullying was compared using the χ2 test. Adjusted means (standard error [SE]) of CES-D values between groups with and without workplace bullying experience were compared using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) after adjusting for possible confounding factors such as age, education status, marital status, years of service, working hours, income, occupational stress, and burnout. Multiple logistic regression analyses were performed with adjustments for possible confounding variables to determine the association between workplace bullying experiences and depression. The interaction by gender difference was conducted using the likelihood ratio test to compare models with and without multiplicative interaction terms. The level of statistical significance was set at a two-tailed p-value < 0.05. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS version 28.0 (IBM Co., NY, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Demographic Characteristics

In total, 12,344 participants were included, comprising 7,981 (64.7%) male and 4,363 (35.3%) female employees. The mean age of the male employees (37.32±9.64) was significantly older than that of female employees (35.45±9.13). Male employees had significantly longer years of service (t=3.62, p<0.001) and longer weekly working hours (t=6.62, p<0.001) than female employees. While the proportion of highly educated individuals was higher among female employees (χ2=222.80, p<0.001), male employees constituted a higher percentage of those earning higher monthly salaries (χ2=474.04, p<0.001). The proportion of female employees who experienced workplace bullying was higher (χ2=157.39, p<0.001). Female employees experienced higher levels of occupational stress (t=-27.12, p<0.001) and burnout (exhaustion, t=-30.68, p<0.001; disengagement, t=-29.20, p<0.001) compared to male employees. The mean CES-D score of female employees was higher than that of male employees (t=-20.58, p<0.001), and the prevalence of depression was higher in female employees than in male employees (χ2=550.95, p<0.001) (

Table 1).

The baseline characteristics of the groups with and without workplace bullying according to gender are shown in

Table 2. Among male employees, those who experienced workplace bullying were significantly older (t=-5.82, p<0.001), had a higher proportion of highly educated individuals (χ2=12.31, p=0.006), were more likely to be married (χ2=19.88, p<0.001), had longer years of service (t=-2.28, p=0.023) and weekly working hours (t=-3.37, p=0.001), and a higher proportion of those receiving higher monthly salaries (χ2=9.25, p=0.026) than non-bullied male employees. Among female employees who experienced workplace bullying, there were no significant differences in age, education level, or years of service compared to non-bullied female employees. However, bullied female employees had a higher proportion of unmarried individuals (χ2=16.37, p=0.001), longer weekly working hours (t=-2.69, p=0.007), and a higher proportion of those receiving lower monthly salaries (χ2=8.87, p=0.031). Among both genders, those who experienced workplace bullying exhibited higher levels of occupational stress (male employees, t=-32.04, p<0.001; female employees, t=-21.71, p<0.001), exhaustion from burnout (male employees, t=-24.68, p<0.001; female employees, t=-17.50, p<0.001), disengagement from burnout (male employees, t=-23.24, p<0.001; female employees, t=-15.93, p<0.001), and severity of depressive symptoms (male employees, t=-24.76, p<0.001; female employees, t=-16.41, p<0.001), as well as a higher prevalence of depression (male employees, χ2=500.64, p<0.001; female employees, χ2=177.69, p<0.001), compared to non-bullied employees.

3.2. Comparison of the Prevalence of Depression and CES-D Score Between Bullied and non-bullied Groups

The prevalence of depression between groups with and without workplace bullying experiences is presented in

Table 3. The prevalence of depression among male employees was significantly higher in the bullied group (71.1%) than in the non-bullied group (31.9%). Among female employees, the bullied group had a higher prevalence of depression (78.8%) than the non-bullied group (53.2%).

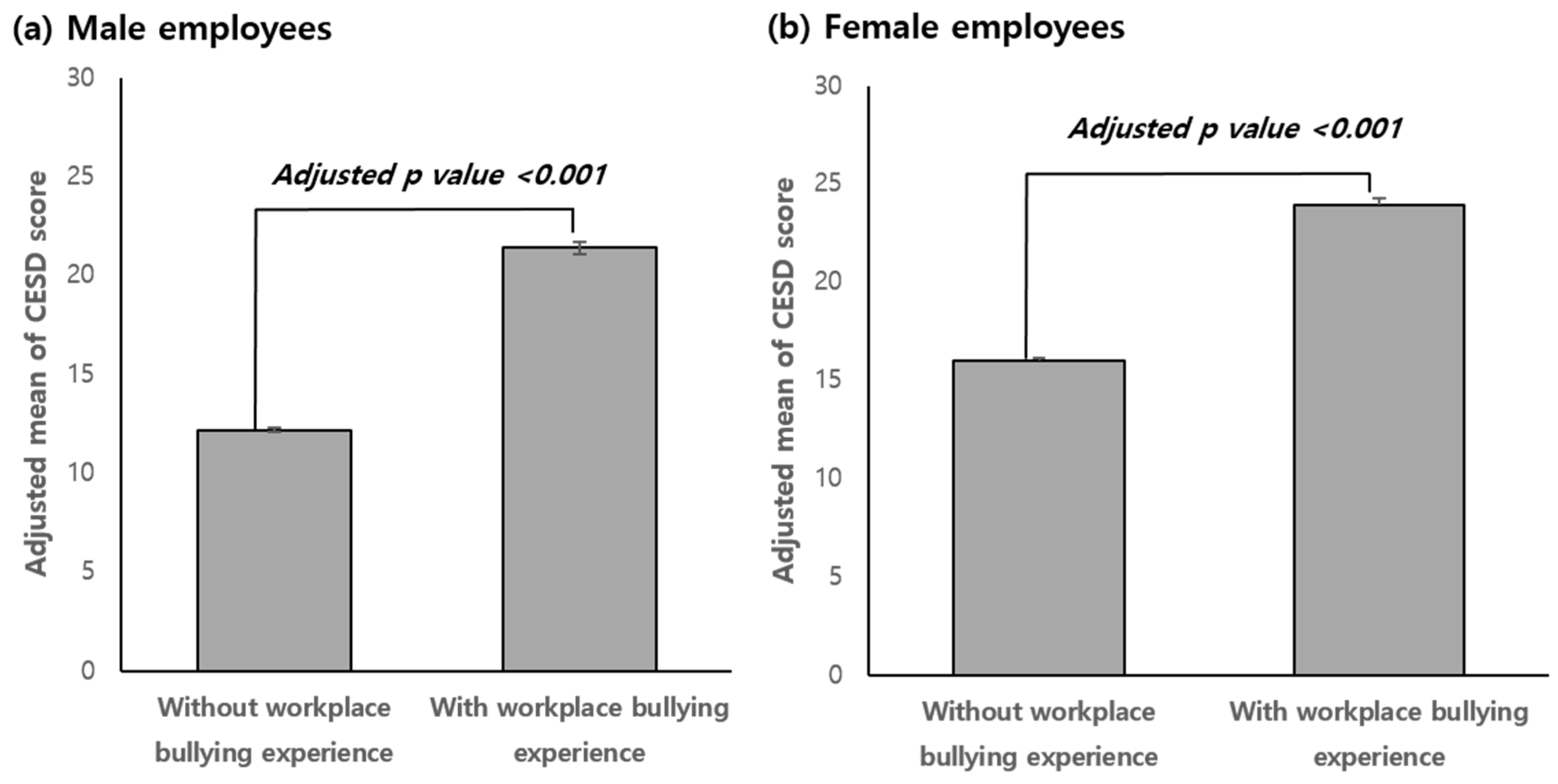

Figure 1 shows a comparison of CES-D scores (as a continuous variable) according to the experience of workplace bullying among male and female employees. In male employees, after adjusting for possible confounding factors such as age, education status, marital status, years of service, working hours, income, occupational stress, and burnout, the adjusted mean of the CES-D was significantly higher in the bullied group (adjusted mean[SE]=16.38[0.24]) than in the non-bullied group (adjusted mean[SE]=12.76[0.77]). (adjusted p<0.001), respectively. Among female employees, the bullied group (adjusted mean[SE]=19.50[0.30]) had a higher adjusted mean CES-D score than the non-bullied group (adjusted mean[SE]=16.89[0.13]) (adjusted p<0.001).

3.3. Association Between Depression and the Experience of Workplace Bullying

The results of the logistic regression analysis used to examine the factors associated with the prevalence of depression are described in

Table 2 and

Table 3. To explain the prevalence of depression, Model 1 included variables such as age, educational level, marital status, years of service, working hours, and monthly salary. Model 2 expanded on this by incorporating occupational stress and burnout variables. In Model 3, the presence of workplace bullying experience was added to examine whether the explanatory power increased. For both male and female employees, the results showed a gradual increase in the explanatory power of the models, which progressed from Model 1 (male employees, 2.0%; female employees, 5.2%) to Models 2 (male employees, 45.5%; female employees, 40.1%) and 3 (male employees, 46.3%; female employees, 40.6%).

Table 4 shows the results of the multivariate logistic regression analyses after adjusting for confounding factors for the association between workplace bullying experiences and the prevalence of depression. In both male and female employees, in the fully adjusted model, bullied employees were at an increased risk of having depression than non-bullied employees (adjusted OR [95% CI] for male employees, 2.21 [1.93–2.67]; for female employees, 1.65 [1.33–2.04]). The association between workplace bullying experiences and depression was stronger in male employees than in female employees (p for interaction<0.001) (

Table 5).

4. Discussion

Our study examined the relationship between workplace bullying and the prevalence of depression among Korean employees, with a focus on understanding the role of gender in this relationship. We found a significant positive association between workplace bullying and the prevalence of depression. Notably, this association is more pronounced among male employees. These findings not only provide important insights into the gender-specific effects of workplace bullying on mental health but also mark the first largescale examination of the differing im-pacts of workplace bullying on the prevalence of depression among male and female employees in the Republic of Korea.

In our study, female employees reported significantly higher instances of workplace bullying compared to their male counterparts. Male employees who had experienced workplace bully-ing tended to be older, more educated, married, with longer years of service, working longer weekly hours, and earning a higher income. Conversely, female employees who experienced work-place bullying tended to be unmarried, working longer weekly hours, and earning lower incomes. These patterns suggest that female employees might face bullying in the early career stages, while male employees could face bullying later due to workplace competition, especially among higher-educated and higher-income individuals. This is consistent with other studies showing that regardless of the field of employment, a larger number of female employees are bullied in the workplace; more-over, female employees are more vulnerable to becoming targets of workplace bullying, especially when they work in lower hierarchical positions within organizations [

18]. Conversely, male employees experience bullying regardless of their positions within their organizations [

18]. This highlights the importance of ongoing efforts to understand and address the gender-specific dynamics and impacts of workplace bullying.

Our findings demonstrate that employees of both genders, who have experienced workplace bullying, also significantly experience higher workplace stress, higher burnout, and greater severity and prevalence of depressive symptoms. Specifically, workplace bullying increased the risk of depression by 2.21 times and 1.65 times in male and female employees, respectively. This finding highlights workplace bullying as a major risk factor for depression. These results align with those of several studies con-ducted in Italy [

1], Norway [

12], Germany [

19,

20], Finland [

21], Denmark [

22,

23], and Malaysia [

24], which reported a significant relationship between workplace bullying and the prevalence of depression. In the Republic of Korea, research on call center em-ployees has demonstrated a significant correlation between workplace bullying and an increased prevalence of depression [

25]. This positive association observed between workplace bul-lying and the prevalence of depression can be explained by vari-ous stress models that highlight the negative effects of prolonged stress on both physical and mental health. Workplace bullying can be considered a source of prolonged social defeat stress that may affect emotional well-being, likely through changes in neu-roendocrine, autonomic, and immune functions [

23,

26]. One study found that workplace bullying was indirectly related to life satisfaction via job-related anxiety and insomnia [

27]. Additionally, prolonged periods of stress resulting from workplace bullying may lead to the development of mood disorders and increased allostatic load, which can negatively impact both physical and mental health [

28].

Our novel finding is that workplace bullying substantially increased the prevalence of depression in both genders, with a notably higher risk for male employees than for female employees. Previous studies on the gender-specific impact of bullying on mental health have reported mixed outcomes. One study suggested that being male could serve as a protective factor, pre-serving mental health despite experiencing workplace bullying [

11]. However, another study found that while female employees generally reported experiencing more workplace bullying [

12,

29], the impact on mental health was more pronounced among male employees [

12], which aligned with our findings. Similarly, a study conducted among Italian employees found that, although female employees were more likely to perceive bullying, the as-sociation between severe forms of bullying and mental disorders was stronger among male employees [

30].

There are two primary explanations for the greater impact of workplace bullying on the mental health of male employees. First, the impact of workplace bullying on male employees' mental health may be exacerbated by the perception that their success in the workplace is under threat. Men often associate their roles as fathers and husbands with economic contributions to the family [

31]. Therefore, unemployment and workplace instability significantly affect mental health [

32]. Experiencing bullying at work could be perceived as a threat to their ability to fulfill this role, potentially leading to feelings of hopelessness [

29]. In our study, male employees who were more educated, worked longer hours, and had higher incomes reported more instances of work-place bullying, suggesting that bullying could become more prevalent as they gained a competitive advantage over time. This perception is especially pronounced in Korea’s collectivist culture, where professional success and career progression rely heavily on interpersonal relationships at the workplace. Second, male employees may have a higher threshold for reporting workplace bullying, particularly when studies rely on self-reporting methods [

33]. Consequently, it takes more expo-sure for a man to admit to being bullied, and the level of expo-sure to bullying behaviors is higher for men, with more serious consequences [

33]. This could be particularly true for Korean male employees, most of whom have mandatory military experience and are influenced by patriarchal norms that equate resilience with masculinity and view admitting to being bullied as a sign of weakness. In our dataset, the proportion of male employees who reported bullying experiences was notably lower than that of female employees, which supported this explanation. Understanding these gender differences and cultural nuances is crucial for addressing workplace bullying and its impact on mental health.

This study had several limitations. First, the participants selected from among those who underwent mental health examinations at Kangbuk Samsung Hospital may not fully represent all employees, potentially affecting the generalizability of our findings. Although our study did not differentiate participants by occupation, this broad approach uniquely contributes to the understanding of employee mental health in general. Future research could benefit from exploring specific occupational groups. Second, our study's cross-sectional design limited our ability to establish causality between workplace bullying and the prevalence of depression, suggesting the need for longitudinal studies. Despite controlling for several demographic variables, unaccounted-for and confounding variables may still exist. Finally, our reliance on self-reported measures could have introduced response bias, although we excluded careless responses. Future investigations could enhance accuracy by using objective measures to study the effects of workplace bullying on the prevalence of depression.

5. Conclusions

Our study provides evidence of a significant positive association between workplace bullying and the prevalence of depression among Korean employees, and this association is more pro-nounced among male employees. The results highlight the need to address mental health issues, potentially through the provision of resources, support services, and the development of an-ti-bullying policies, given the association between workplace bullying and the prevalence of depression among male employees. Our findings have significant implications, especially for Korean males required to complete military service, where de-pression and suicide have been identified as potential issues [

34]. Future research could expand on our work by exploring the relationship between workplace bullying and the prevalence of de-pression across diverse demographic groups using various methodologies. The role of other potential factors and the effectiveness of various interventions in this relationship should also be explored to develop more effective strategies for preventing workplace bullying and promoting employee well-being.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Min-Kyoung Kim and Sung Joon Cho; methodology, Sra Jung and Heejun Lee; software, Sra Jung and Heejun Lee; validation, Min-Kyoung Kim and Sung Joon Cho; formal analysis, Mi Yeon Lee; in-vestigation, Sra Jung and Heejun Lee; resources, Sang-Won Jeon, Dong-Won Shin, Young-Chul Shin and Kang-Seob Oh; data curation, Sang-Won Jeon, Dong-Won Shin, Young-Chul Shin and Kang-Seob Oh; writing—original draft preparation, Sra Jung and Heejun Lee; writ-ing—review and editing, Sra Jung and Heejun Lee; visualization, Sra Jung; supervision, Kang-Seob Oh, Min-Kyoung Kim, and Sung Joon Cho; project administration, Min-Kyoung Kim and Sung Joon Cho; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital and adhered to the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki and the principles of Good Clinical Practice (approval number: KBSMC 2022-03-046).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived because only de-identified data routinely collected during health screening visits were used.

Data Availability Statement

The data necessary to interpret, replicate, and build upon the methods or findings reported in this article are available upon request from the cor-responding author, S.C. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions that protect patient privacy and consent.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lo Presti, A.; Pappone, P.; Landolfi, A. The Associations Between Workplace Bullying and Physical or Psychological Negative Symptoms: Anxiety and Depression as Mediators. Eur J Psychol 2019, 15, 808-822. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magee, C.; Gordon, R.; Robinson, L.; Caputi, P.; Oades, L. Workplace bullying and absenteeism: The mediating roles of poor health and work engagement. Human Resource Management Journal 2017, 27, 319-334. [CrossRef]

- Lutgen-Sandvik, P.; Namie, G.; Namie, R. Workplace bullying: Causes, consequences, and corrections. Destructive organizational communication 2010, 43-68.

- Loerbroks, A.; Weigl, M.; Li, J.; Glaser, J.; Degen, C.; Angerer, P. Workplace bullying and depressive symptoms: a prospective study among junior physicians in Germany. J Psychosom Res 2015, 78, 168-172. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, Y.Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.J.; Liao, H.Y.; Liao, Y.M.; Chen, H.M. Determinants of Workplace Bullying Types and Their Relationship With Depression Among Female Nurses. J Nurs Res 2020, 28, e92. [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.A. Hofstede’s cultural dimensions: Comparison of South Korea and the United States. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2015 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference, Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 1–2.

- Yoo, G.; Lee, S. It Doesn't End There: Workplace Bullying, Work-to-Family Conflict, and Employee Well-Being in Korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018, 15. [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.N. The role of culture on workplace bullying: the comparison between the UK and South Korea. University of Nottingham, 2010.

- Yoon, S.; Kim, Y.-K. Gender Differences in Depression. In Understanding Depression : Volume 1. Biomedical and Neurobiological Background, Kim, Y.-K., Ed.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2018; pp. 297-307.

- Salin, D. Risk factors of workplace bullying for men and women: the role of the psychosocial and physical work environment. Scand J Psychol 2015, 56, 69-77. [CrossRef]

- Skuzińska, A.; Plopa, M.; Plopa, W. Bullying at Work and Mental Health: The Moderating Role of Demographic and Occupational Variables. Adv Cogn Psychol 2020, 16, 13-23. [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, S.; Nielsen, M.B. Workplace bullying as an antecedent of mental health problems: a five-year prospective and representative study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2015, 88, 131-142. [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.J.; Koh, S.B.; Kang, D.; Kim, S.A.; Kang, M.G.; Lee, C.G.; Chung, J.J.; Cho, J.J.; Son, M.; Chae, C.H. Developing an occupational stress scale for Korean employees. Korean Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2005, 17, 297-317. [CrossRef]

- Kang, J. Validation of the Korean Version of Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (K-OLBI). The Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 21 2023, 14, 4129-4143. [CrossRef]

- Noh, S.; Kaspar, V.; Chen, X. Measuring depression in Korean immigrants: assessing validity of the translated Korean version of CES-D scale. Cross-Cultural Research 1998, 32, 358-377. [CrossRef]

- Heo, E.-H.; Choi, K.-S.; Yu, J.-C.; Nam, J.-A. Validation of the center for epidemiological studies depression scale among Korean adolescents. Psychiatry investigation 2018, 15, 124. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, R.E.; Rhoades, H.M.; Vernon, S.W. Using the CES-D scale to screen for depression and anxiety: Effects of language and ethnic status. Psychiatry research 1990, 31, 69-83. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maidaniuc-Chirilă, T. Gender differences in workplace bullying exposure. Journal of Psychological & Educational Research 2019, 27.

- Lange, S.; Burr, H.; Rose, U.; Conway, P.M. Workplace bullying and depressive symptoms among employees in Germany: prospective associations regarding severity and the role of the perpetrator. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2020, 93, 433-443. [CrossRef]

- Kostev, K.; Rex, J.; Waehlert, L.; Hog, D.; Heilmaier, C. Risk of psychiatric and neurological diseases in patients with workplace mobbing experience in Germany: a retrospective database analysis. Ger Med Sci 2014, 12, Doc10. [CrossRef]

- Kivimäki, M.; Virtanen, M.; Vartia, M.; Elovainio, M.; Vahtera, J.; Keltikangas-Järvinen, L. Workplace bullying and the risk of cardiovascular disease and depression. Occup Environ Med 2003, 60, 779-783. [CrossRef]

- Rugulies, R.; Madsen, I.E.; Hjarsbech, P.U.; Hogh, A.; Borg, V.; Carneiro, I.G.; Aust, B. Bullying at work and onset of a major depressive episode among Danish female eldercare workers. Scand J Work Environ Health 2012, 38, 218-227. [CrossRef]

- Bonde, J.P.; Gullander, M.; Hansen Å, M.; Grynderup, M.; Persson, R.; Hogh, A.; Willert, M.V.; Kaerlev, L.; Rugulies, R.; Kolstad, H.A. Health correlates of workplace bullying: a 3-wave prospective follow-up study. Scand J Work Environ Health 2016, 42, 17-25. [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.M.H.; Wong, J.E.; Yeap, L.L.L.; Wee, L.H.; Jamil, N.A.; Swarna Nantha, Y. Workplace bullying and psychological distress of employees across socioeconomic strata: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 608. [CrossRef]

- The relationship between emotional labor, workplace bullying, depression and subjective well-being of employees in call centers. Korean Journal of social welfare research 2022, 72, 5-34.

- Hansen Å, M.; Hogh, A.; Persson, R. Frequency of bullying at work, physiological response, and mental health. J Psychosom Res 2011, 70, 19-27. [CrossRef]

- Nauman, S.; Malik, S.Z.; Jalil, F. How Workplace Bullying Jeopardizes Employees' Life Satisfaction: The Roles of Job Anxiety and Insomnia. Front Psychol 2019, 10, 2292. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwen, B.S.; Karatsoreos, I.N. Sleep Deprivation and Circadian Disruption: Stress, Allostasis, and Allostatic Load. Sleep Med Clin 2015, 10, 1-10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attell, B.K.; Kummerow Brown, K.; Treiber, L.A. Workplace bullying, perceived job stressors, and psychological distress: Gender and race differences in the stress process. Soc Sci Res 2017, 65, 210-221. [CrossRef]

- Nolfe, G.; Petrella, C.; Zontini, G.; Uttieri, S.; Nolfe, G. Association between bullying at work and mental disorders: gender differences in the Italian people. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2010, 45, 1037-1041. [CrossRef]

- Simon, R.W. Gender, multiple roles, role meaning, and mental health. J Health Soc Behav 1995, 36, 182-194. [CrossRef]

- Artazcoz, L.; Benach, J.; Borrell, C.; Cortès, I. Unemployment and mental health: understanding the interactions among gender, family roles, and social class. Am J Public Health 2004, 94, 82-88. [CrossRef]

- Rosander, M.; Salin, D.; Viita, L.; Blomberg, S. Gender Matters: Workplace Bullying, Gender, and Mental Health. Front Psychol 2020, 11, 560178. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, C.G.; Jung, J.; Yoon, J.H.; Lee, D.; Jeon, H.; Lee, S.Y. How Is the Suicide Ideation in the Korean Armed Forces Affected by Mental Illness, Traumatic Events, and Social Support? J Korean Med Sci 2021, 36, e96. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).