1. Introduction

Acute respiratory infections result in significant morbidity and mortality worldwide, and are commonly caused by viruses including influenza viruses, parainfluenza viruses, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), human rhinoviruses, human metapneumovirus and coronaviruses [

1]. Following the relaxation of infection control measures implemented during the pandemic COVID-19 period, an increase in transmission of these respiratory viruses has been reported [

2]. In equatorial Malaysia, with COVID-19 remaining endemic, there is year-round incidence of influenza [

3] with no distinct seasonality, unlike countries in temperate regions. Patients may present with some of these symptoms including cough, runny nose, sore throat, breathlessness, wheezing, headache and fever. Differentiating these respiratory viruses solely based on clinical presentation is challenging due to their similar, non-specific signs and symptoms. With the recent COVID-19 pandemic, the need for rapid and robust diagnostic tools has gained more attention, not only for the institution of appropriate treatment but also for timely infection control measures and perhaps an early signal to detect a future potential outbreak [

4].

The current diagnostic tools for detecting common respiratory viruses include reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay, virus culture, antigen detection and antibody detection [

5]. Real-time RT-PCR tests are the gold standard, but may need several steps including extraction and amplification, and require trained staff and costly laboratory set-up [

6]. The diagnostic usefulness of virus culture is limited as the test is not widely available and may take up to 10-14 days. Although antigen and antibody detection are cheaper with shorter turn-around time, the sensitivity and the specificity are lower compared to real-time RT-PCR, depending on the viral load of the specimen for antigen detection, and antibody response of the infected patients [

5]. Thus, a simple, rapid and robust assay with diagnostic performance comparable to real-time RT-PCR is needed to overcome these diagnostic limitations. Differentiating these respiratory viruses is crucial not only to facilitate timely optimum treatment but also for the institution of infection control measures. With increasing demands in the market, several manufacturers have taken steps in developing rapid detection and point-of-care test kits for the simultaneous detection of influenza A virus (IAV), influenza B virus (IBV), RSV and SARS-CoV-2 virus [

7].

The STANDARD M10 Flu/RSV/SARS-CoV-2 (SD Biosensor Inc, Seoul, Korea) is a fully automated, scalable, rapid assay that enables simultaneous differentiation and detection of IAV, IBV, RSV and SARS-CoV-2 virus from a single specimen. This assay uses a single device with results available in one hour [

7]. Sample processing, nucleic acid extraction and amplification take place in a fully automated, closed system, requiring minimal training and monitoring with less cross-contamination risk.

The objective of this study is to evaluate the diagnostic performance of the STANDARD M10 Flu/RSV/SARS-CoV-2 assay in comparison to Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2 or Xpert Xpress Flu/RSV (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, USA) as a comparator test.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples collection and study design

This retrospective study was conducted using residual respiratory samples from patients presenting with respiratory infections sent to the diagnostic virology unit of Universiti Malaya Medical Centre (UMMC), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. The samples were stored at -80℃ and retrieved for this study.

At least 45 positive samples for each virus (IAV, IBV, RSV and SARS-CoV-2) and 150 negative samples were collected. To achieve the desired sample sizes, positive respiratory samples with IAV, IBV or RSV from May 2013 to January 2023, and positive samples for SARS-CoV-2 from February 2022 to January 2023 were retrieved. These samples were confirmed using a composite gold standard of multiple tests, such as immunofluorescence (IF), virus culture or PCR, with at least one of the tests reported positive.

The samples were tested with both STANDARD M10 and either Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2 or Xpert Xpress Flu/RSV as the index test and comparator test respectively. In brief, once thawed to room temperature, 300 µl of the sample was loaded into each STANDARD M10 and Xpert Xpress cartridge and set up for the automated PCR concurrently. Xpert Xpress Flu/RSV was used if the samples were previously reported as positive for IAV, IBV or RSV, whereas Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2 was used if the samples were previously reported as positive for SARS-CoV-2.

The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), accuracy, and agreement rates were calculated.

2.2. Index test

STANDARD M10 is an all-in-one cartridge-based ready-to-use multiplex RT-PCR assay intended for the qualitative detection of IAV, IBV, RSV and SARS-CoV-2 RNA. It simultaneously detects the M gene for IAV, NS1 gene for IBV, M gene for RSV, and two gene targets (ORF1ab and N) for SARS-CoV-2. For SARS-CoV-2, the detection of at least one target signifies SARS-CoV-2 infection [

7]. Once the sample was vortexed for about 10 seconds, 300 µL was added directly to the cartridge for RT-PCR in the STANDARD M10 analyser according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The limit of detection (LoD) of this assay is 200 copies/ml for the SARS-CoV-2 ORF1ab gene, 400 copies/ml for IAV/IBV, and 800 copies/ml for both RSV and SARS-CoV-2 N genes [

7].

2.3. Comparator test

The Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2 and Xpert Xpress Flu/RSV assays are automated in-vitro diagnostic tools performed on the GeneXpert Xpress Systems which carry out nucleic acid extraction, real-time PCR and analysis. Similar to STANDARD M10, 300 μL of the sample was loaded into the cartridge before PCR setup. The probes and primers used in Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2 amplify and detect the nucleocapsid (N2) and envelope (E) genes of SARS-CoV-2 virus [

8]. Xpert Xpress Flu/RSV detects matrix (M) gene, basic polymerase (PB2) and acidic protein (PA) for IAV, matrix (M) gene and non-structural protein (NS) for IBV, and nucleocapsid (N) for RSV [

9].

2.4. Standard tests

The samples used in this study were previously confirmed with various standard routine tests. SARS-CoV-2 was detected by real-time RT-qPCR SARS-CoV-2, while IAV, IBV and RSV were detected by either immunofluorescence assay or virus culture. IAV and IBV were also detected by multiplex RT-qPCR method that was performed according to protocol 1 of the 2017 WHO guidelines with minor modifications [

10]. A sample was considered positive for IAV, IBV, RSV or SARS-CoV-2, if any one of these standard tests was positive.

2.4.1. RT-qPCR for SARS-CoV-2

Either cobas SARS-CoV-2 (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) or Seegene Allplex SARS-CoV-2 assay (Seegene, Seoul, Korea) were used for detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in respiratory samples. The cobas SARS-CoV-2 assay is fully automated and detects the structural protein envelope (E) gene which is specific for pan-Sarbecovirus and the ORF1 a/b, a non-structural region that is unique to SARS-CoV-2 [

11]. For the Allplex SARS-CoV-2 assay, nucleic acid extraction was carried out separately with a GF-1 Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit (Vivantis Technologies, Shah Alam, Malaysia). Real-time PCR was performed on a CFX96 instrument (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, USA). The Allplex SARS-CoV-2 assay simultaneously detects four different target genes of SARS-CoV-2 (RdRP, S and N genes specific for SARS-CoV-2, and E gene for all Sarbecovirus) [

12]. For both assays, results were analysed and interpreted using pre-installed software.

2.4.2. Immunofluorescence assay

The D3 Ultra 8 Direct Fluorescent Antibody Respiratory Virus Screening & Identification Kit (Diagnostic Hybrids, Athens, USA) was performed on nasopharyngeal aspirates affixed to glass slides to detect a panel of respiratory viruses, including IAV, IBV and RSV [

13].

2.4.3. Virus culture

Samples were inoculated into HEp2, Vero, LLC-MK2, and MDCK cells and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for up to 10 days. Growth of the viruses was then detected by cytopathic effect, and respiratory viruses were identified using immunofluorescence.

2.5. Study endpoint and data analysis

Our study endpoints were to evaluate the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) and accuracy rates of STANDARD M10 compared to Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV2 or Xpert Xpress Flu/RSV. The diagnostic validation parameters were calculated in percentages with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The diagnostic agreement was also tested to measure the result concordance level. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to analyse the Ct value distribution and Spearman correlation was used for Ct value correlation. All data were statistically analysed using GraphPad Prism version 9.0 (GraphPad Prism Software, Boston, USA). The study findings were reported according to the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (STARD) statement (

Appendix A). The use of residual diagnostic respiratory samples was approved by the UMMC medical ethics committee (no. 2022816-11476).

3. Results

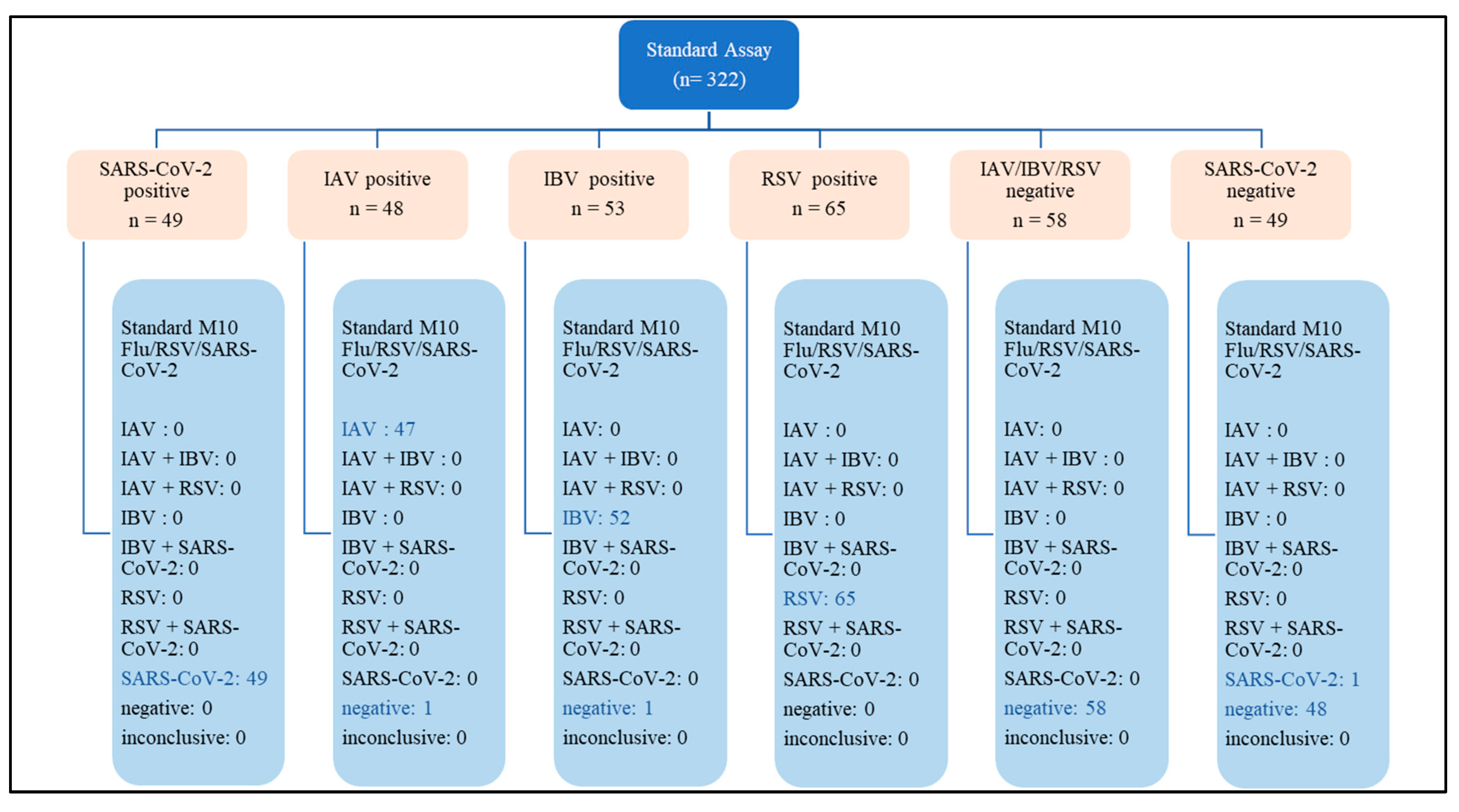

3.1. Final sample size and diagnostic performance of STANDARD M10

A total of 322 respiratory samples were tested with both STANDARD M10 FLU/RSV/SARS-CoV-2 and either Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2 or Xpert Xpress Flu/RSV. This comprised 215 positive samples (48 IAV, 53 IBV, 65 RSV and 49 SARS-CoV-2) and 107 negative samples (58 negative for IAV, IBV and RSV, and 49 negative for SARS-CoV-2) (

Appendix A).

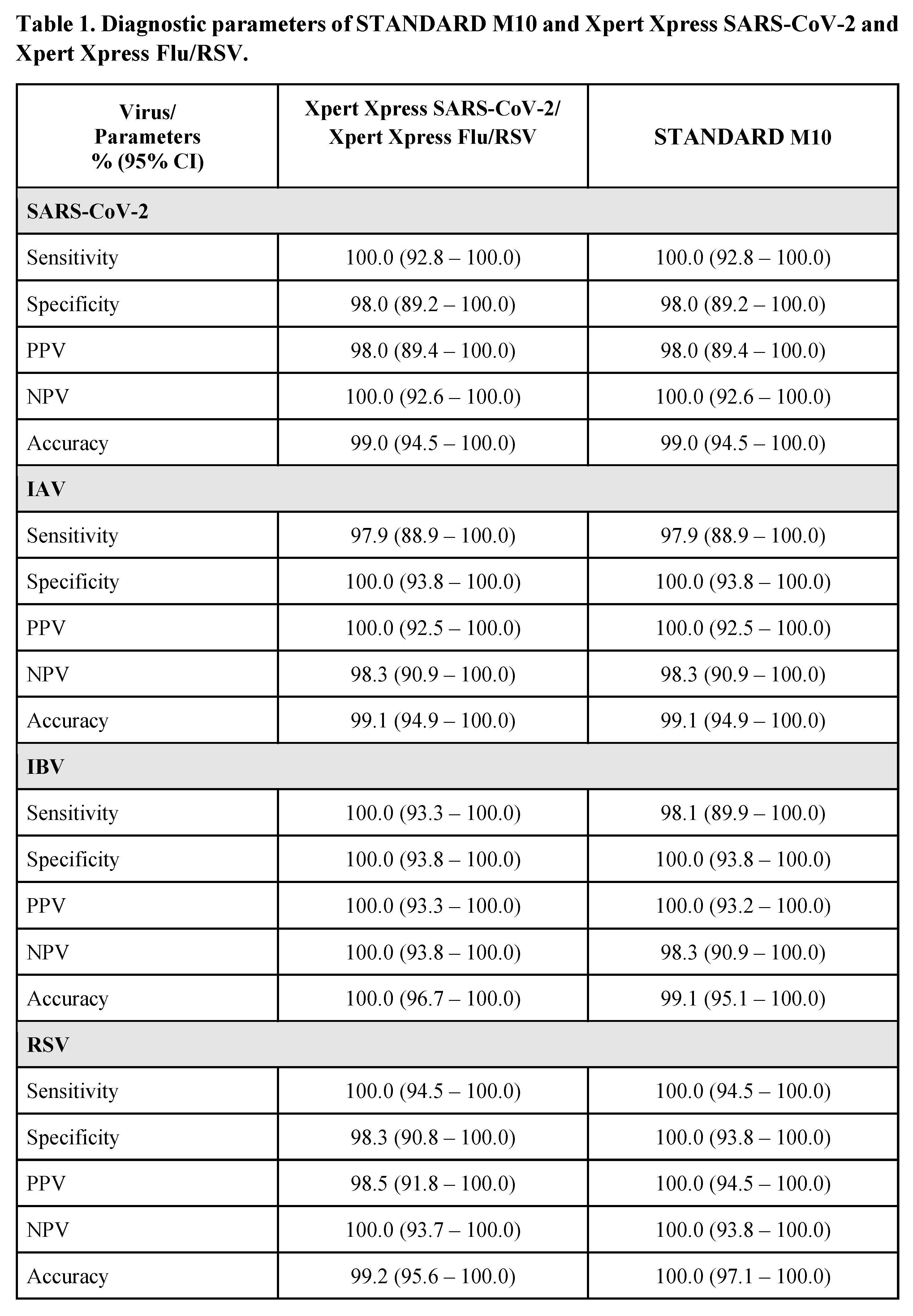

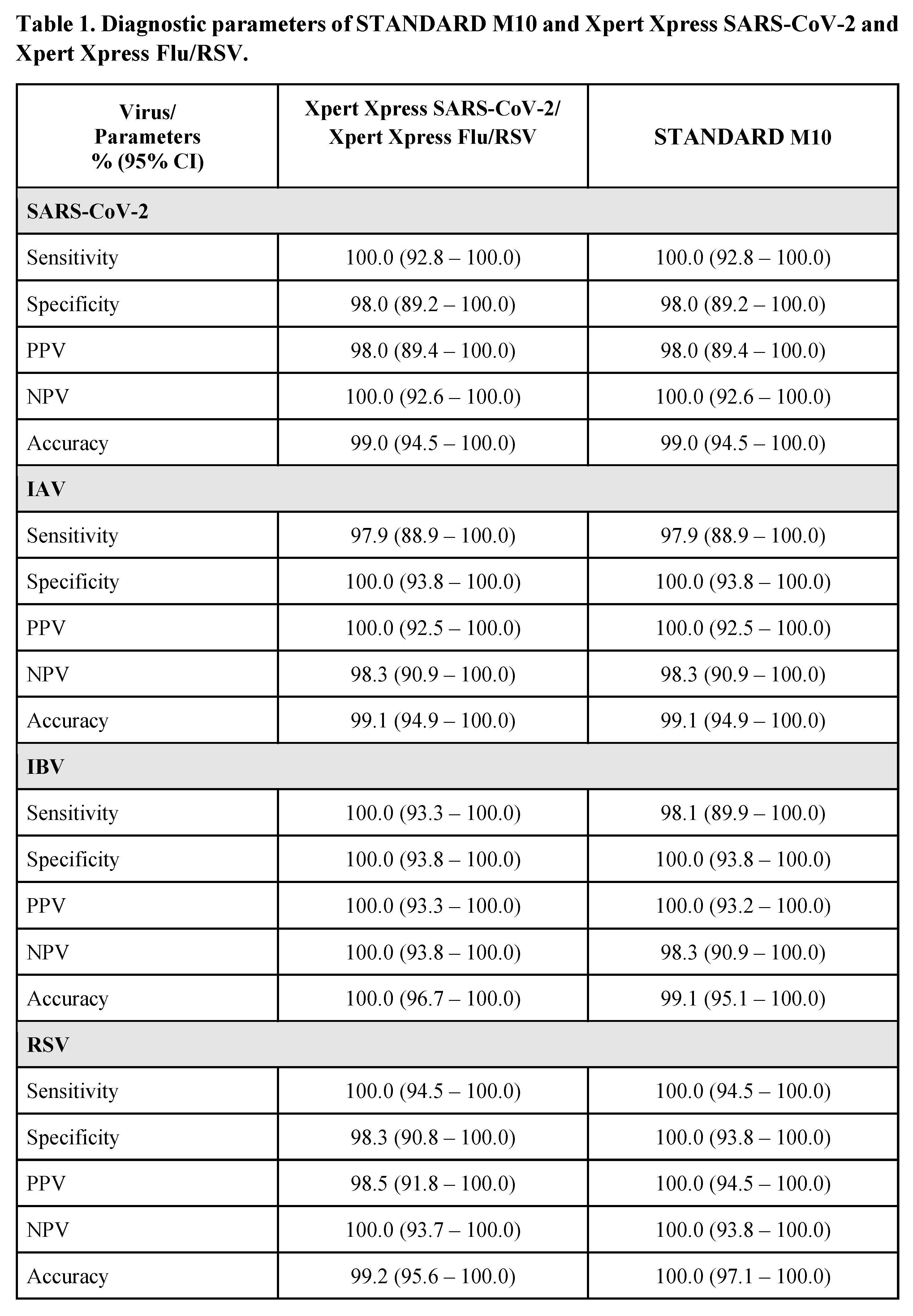

The overall diagnostic parameters (95% confidence interval) for STANDARD M10 and Xpert Xpress are shown in Table 1. For SARS-CoV-2, both STANDARD M10 and Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2 showed identical sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and accuracy, ranging between 98-100%. For IAV, STANDARD M10 and Xpert Xpress Flu/RSV had similar performances with sensitivity of 97.9%, specificity of 100%, PPV of 100%, NPV of 98.3% and accuracy of 99.1%. Non-significant differences were observed for IBV, with STANDARD M10 showing sensitivity, NPV and accuracy rates of 98.1%, 98.3% and 99.1% respectively as compared to 100% for all diagnostic parameters of Xpert Xpress Flu/RSV. For RSV, STANDARD M10 showed 100% rates in all the diagnostic parameters as compared to Xpert Xpress Flu/RSV which showed 100% rates for sensitivity and NPV, 98.3% specificity, 98.5% PPV and 99.2% accuracy; these differences were not significant.

Our study had 3 inaccurate results each from STANDARD M10 and Xpert Xpress assays. STANDARD M10 showed 1 false positive result with SARS-CoV-2 and 1 false negative result for both IAV and IBV. Xpert Xpress had 1 false positive result for both SARS-CoV-2 and RSV, and 1 false negative result for IAV.

There was close overall agreement of 99.4% (95% CI, 97.8 – 99.8%) between STANDARD M10 and Xpert Xpress, 99.1% (95% CI, 96.7 – 99.7) agreement for positive samples and 100% (95% CI, 96.5 – 100.0) agreement for negative samples.

3.2. The correlation between STANDARD M10 and either Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2 or Xpert Xpress Flu/RSV

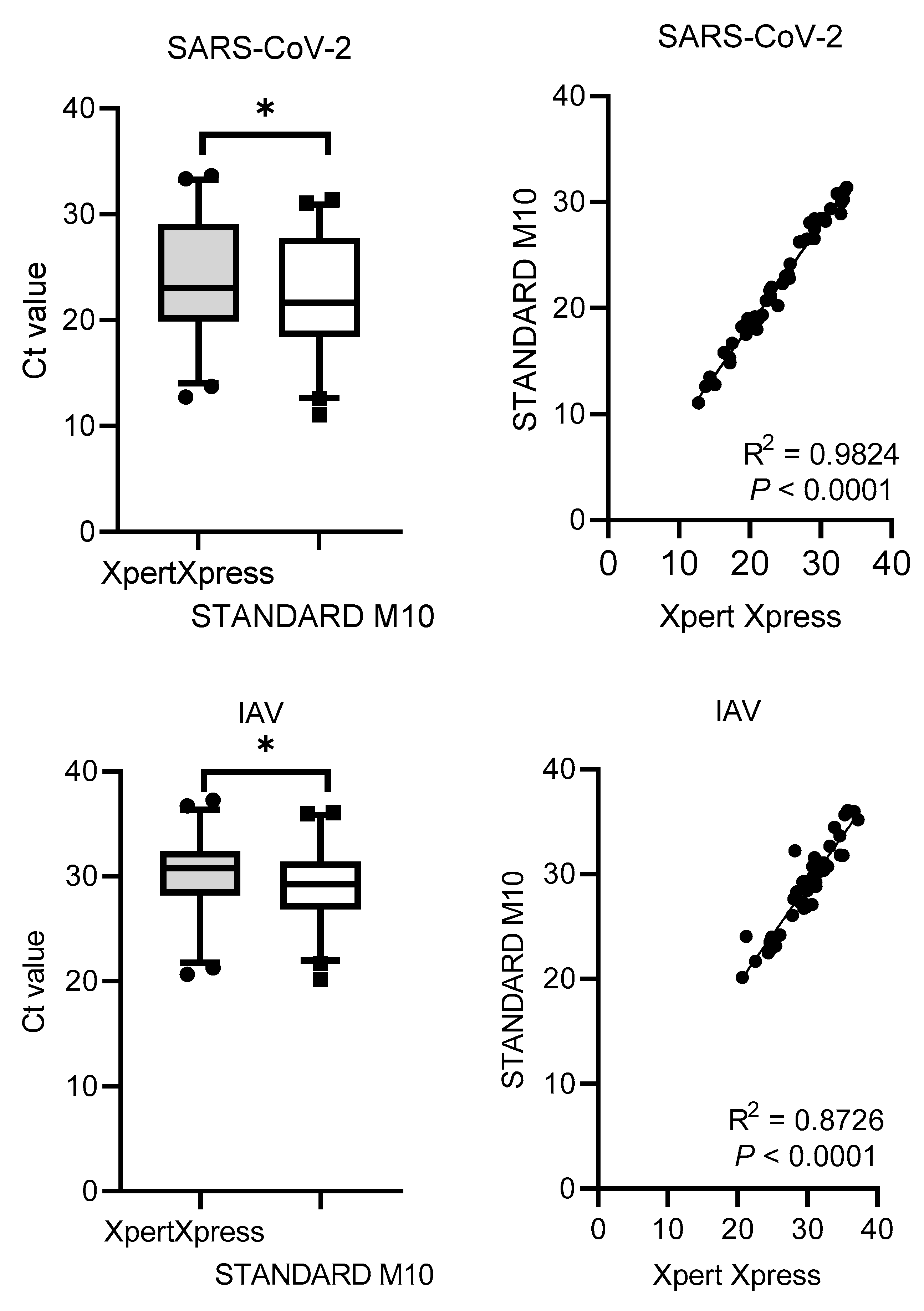

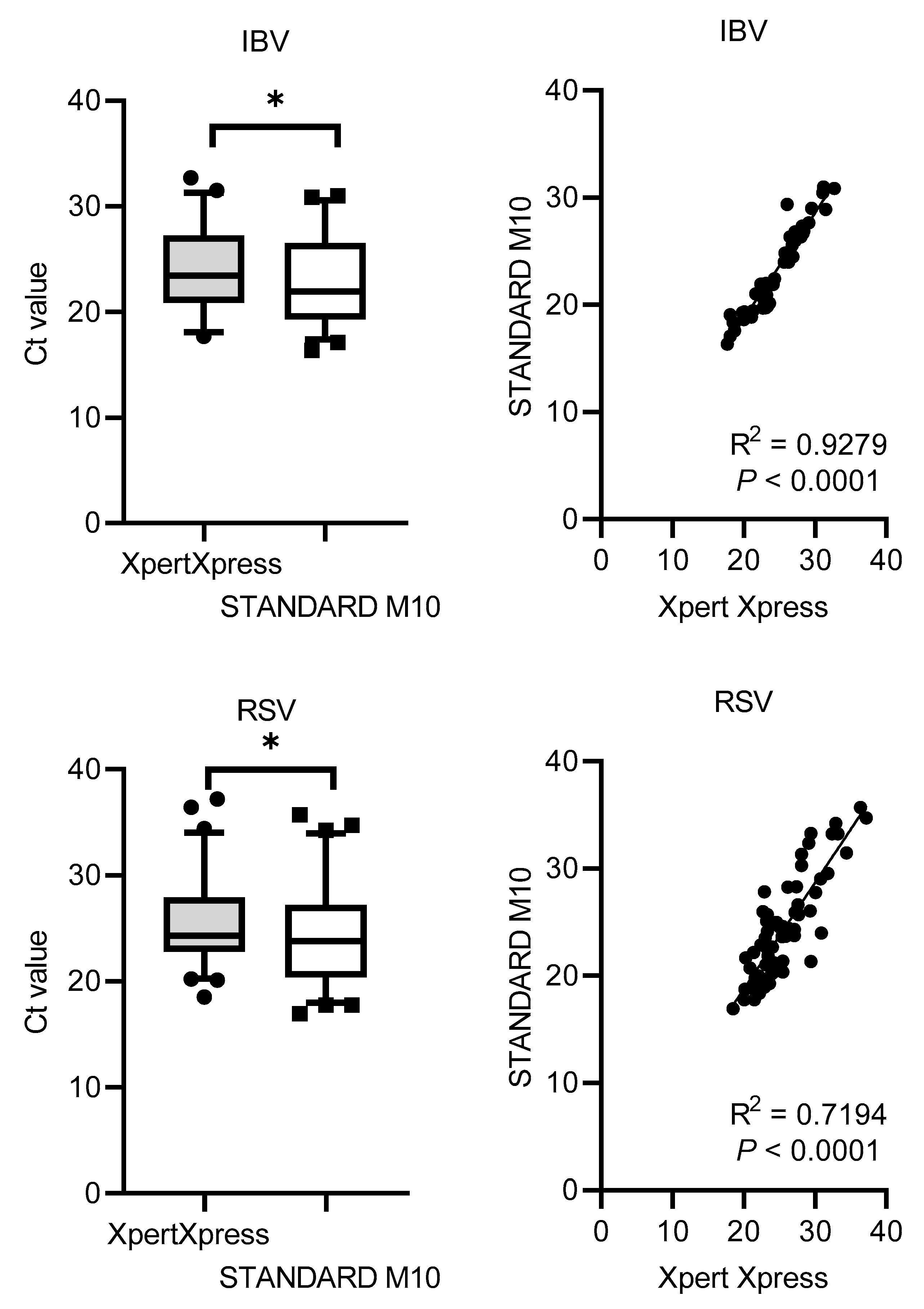

The Ct values distribution and correlation (R

2) comparing STANDARD M10 and Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2 or Xpert Xpress Flu/RSV are shown in

Figure 1. Xpert Xpress recorded significantly higher Ct values for all viruses, with median cycles differences of 1.90 (SD = 0.79) for SARS-CoV-2, 1.13 (SD = 1.41) for IAV, 1.36 (SD = 1.09) for IBV, and 1.76 (SD = 2.54) for RSV. Overall, STANDARD M10 reported lower Ct values by 2 cycles compared to Xpert Xpress. For the Ct value correlation, SARS-CoV-2 had the highest R

2 value of 0.98, followed by IBV with 0.93, IAV with 0.87 and RSV with 0.72 (all

P-values <0.0001).

4. Discussion

Standard tests used for the detection of respiratory viruses have many advantages but also limitations. Cell culture is the “gold standard” for virus discovery [

13] but suffers a few limitations as a routine diagnostic method such as a longer turnaround time, being laborious and carrying a high risk of cell contamination [

6]. Compared to the culture method, immunofluorescence to detect antigen can provide a faster result for early clinical management and infection control measures, but is generally limited due to its moderate sensitivity. These factors have swayed the preference for other diagnostic methods such as rapid point-of-care PCR or rapid antigen tests for timely diagnosis of virus infection [

6].

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, qPCR has gained wide usage. The cobas and Seegene assays offer turnaround times ranging from 2.5 to 3 hours, while GeneXpert and STANDARD M10 offer shorter turnaround times of about an hour without compromising diagnostic performance.

Many studies have reported excellent performance of both Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2 [

4,

14,

15,

16] and Xpert Xpress Flu/RSV [

15,

16]. Our study shows that the recently introduced STANDARD M10 is comparable with these established assays, with overall sensitivity and specificity ranging from 98% to 100% for the detection of all 4 respiratory viruses (Table 1).

STANDARD M10 has an advantage as it enables simultaneous detection of individual viruses from a single sample. As the clinical presentation of SARS-CoV-2 infection can be difficult to differentiate from influenza and RSV [

6], multiple sampling may be needed for testing with the different Xpert Xpress assays. The multiple or repeated sampling not only contributes to patient discomfort but also a longer turnaround time and higher cost if both of the Xpert Xpress tests were to be done separately. The ability of STANDARD M10 to simultaneously differentiate and detect IAV, IBV, RSV and SARS-CoV-2, would be the main advantage of this assay especially for emergency use in settings with poor laboratory facilities.

The first reported evaluation study of STANDARD M10 in Italy showed an overall agreement as high as 94.6%, with positive percent agreement ranging from 96.6% to 100% and negative percent agreement ranging from 98.4% to 100% [

7]. Our study with 322 samples shows consistent findings with this study, reflecting the comparable performance of STANDARD M10 in different regions of the world. Our study also used samples as early as 2022 for SARS-CoV-2, 2018 for IAV, and 2013 for IBV and RSV, suggesting that STANDARD M10 can detect a wide range of viruses that have evolved over time.

The pre-set cut-off Ct value is 40 for STANDARD M10 and 45 for Xpert Xpress. However, Ct values are an unreliable surrogate for determining viral load, infectivity or transmissibility of the viruses [

17]. The Ct values may be affected by the nucleic acid extraction, primer designing, assay sensitivity (limit of detection) and Ct value determination method of various assays [

18]. Thus, these inter-test variabilities of Ct values between various rtRT-PCR are not critical and have also been reported in other studies [

17].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, STANDARD M10 demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity for the detection of IAV, IBV, RSV and SARS-CoV-2 virus from clinical respiratory samples. The diagnostic performance of STANDARD M10 is comparable to the established Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2 or Xpert Xpress Flu/RSV assays. With the capabilities for simultaneous detection of these 4 important respiratory viruses from a single sample within an hour, in addition to the fully automated system, STANDARD M10 can be used as a point-of-care test assay in emergency or critical care departments, or facilities without sophisticated laboratory set-ups. This assay is particularly useful in tropical countries like Malaysia which have year-round, endemic influenza and COVID-19.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Azwani Abdullah, I-Ching Sam and Yoke Fun Chan; Formal analysis, Azwani Abdullah, I-Ching Sam, Yin Jie Ong, Chun Hao Theo, Muhammad Harith Pukhari and Yoke Fun Chan; Funding acquisition, Yoke Fun Chan; Investigation, Azwani Abdullah, I-Ching Sam, Yin Jie Ong, Chun Hao Theo and Yoke Fun Chan; Methodology, Azwani Abdullah, I-Ching Sam, Yin Jie Ong, Chun Hao Theo, Muhammad Harith Pukhari and Yoke Fun Chan; Project administration, Yoke Fun Chan; Resources, I-Ching Sam; Software, Yin Jie Ong, Chun Hao Theo and Muhammad Harith Pukhari; Supervision, I-Ching Sam and Yoke Fun Chan; Validation, Azwani Abdullah, I-Ching Sam, Muhammad Harith Pukhari and Yoke Fun Chan; Writing – original draft, Azwani Abdullah; Writing – review & editing, I-Ching Sam and Yoke Fun Chan. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by SD BioSensor, Inc, (project code IF073-2022) and Universiti of Malaya (project code MG016-2023). The funders had no role in data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee, Universiti Malaya Medical Centre (MREC ID NO: 2022816-11476) on 18 August 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to patient privacy and data restrictions.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Diagnostic Virology Laboratory, UMMC for help with the clinical specimen collection.

Conflicts of Interest

Yoke Fun Chan and I-Ching Sam have attended a meeting sponsored by SD Biosensor. Yoke Fun Chan has also received an honorarium from the funders. The remaining co- authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A. A total of 322 samples included in the study reported according to Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (STARD)

References

- Zimmerman, R. K.; Balasubramani, G. K.; D’Agostino, H.; Clarke, L.; Yassin, M.; Middleton, D. B.; Silveira, F. P.; Wheeler, N.; Landis, J.; Peterson, A.; Suyama, J.; Weissman, A.; Nowalk, M. P. Population-based Hospitalization Burden Estimates for Respiratory Viruses, 2015–2019. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses 2022, 16, 1133–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amar, S.; Avni, Y. S.; O’Rourke, N.; Michael, T. Prevalence of Common Infectious Diseases after COVID-19 Vaccination and Easing of Pandemic Restrictions in Israel. JAMA Network Open 2022, 5, e2146175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khor, C.-S.; Sam, I.-C.; Hooi, P. S.; Quek, K. F.; Chan, Y. F. Epidemiology and Seasonality of Respiratory Viral Infections in Hospitalized Children in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: A Retrospective Study of 27 Years. BMC Pediatrics 2012, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loeffelholz, M. J.; Alland, D.; Butler-Wu, S. M.; Pandey, U.; Perno, C. F.; Nava, A.; Carroll, K. C.; Mostafa, H. H.; Davies, E.; McEwan, A.; Rakeman, J. L.; Fowler, R. C.; Pawlotsky, J.-m.; Fourati, S.; Banik, S.; Banada, P. P.; Swaminathan, S.; Chakravorty, S.; Kwiatkowski, R.; Chu, V. C.; Kop, J. A.; Gaur, R. L.; Sin, M. L. Y.; Nguyen, D. H. N.; Singh, S.; Zhang, N.; Persing, D. H. Multicenter Evaluation of the Cepheid Xpert Xpress SARS-COV-2 Test. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2020, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ham, S. Y.; Jeong, H.; Jung, J.; Kim, E. S.; Park, K. U.; Kim, H. B.; Park, J. S.; Song, K. H. Performance of STANDARD M10 SARS-CoV-2 Assay for the Diagnosis of COVID-19 from a Nasopharyngeal Swab. Infection and Chemotherapy 2022, 54, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, Y. M.; Tan, X. H.; Hooi, P. S.; Lee, L. M.; Sam, I.-C.; Chan, Y. F. Evaluation of Rapid Influenza Diagnostic Tests for Influenza A and B in the Tropics. Journal of Medical Virology 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domnich, A.; Bruzzone, B.; Trombetta, C.-S.; De Pace, V.; Ricucci, V.; Varesano, S.; Garzillo, G.; Ogliastro, M.; Orsi, A.; Icardi, G. Rapid Differential Diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2, Influenza A/B and Respiratory Syncytial Viruses: Validation of a Novel RT-PCR Assay. Journal of Clinical Virology 2023, 161, 105402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepheid. GeneXpert®: Xpert® Xpress SARS-CoV-2, 2022. Instructions for Use: For Use with GeneXpert Dx System or GeneXpert Infinity System. https://www.cepheid.com/content/dam/www-cepheid-com/documents/package-insert-files/xpress-sars-cov-2/Xpert%20Xpress%20SARS-CoV-2%20Assay%20ENGLISH%20Package%20Insert%20302-3562%20Rev.%20G.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Cepheid. GeneXpert®: Xpert® Xpress Flu/RSV, 2020. Instructions for Use: For Use with GeneXpert Xpress System (point of care system). https://www.cepheid.com/content/dam/www-cepheid-com/documents/package-insert-files/Xpress-Flu-RSV-US-IVD-ENGLISH-Package-Insert-301-7239-Rev.%20D.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- World Health Organization. WHO information for the molecular detection of influenza viruses. 2017. https://www.who. int/influenza/gisrs_laboratory/WHO_information_for_the_molecular_ detection_of_influenza_viruses_20171023_Final.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Cobas®. cobas® SARS-CoV-2, 2022. Qualitative assay for use on the cobas® 6800/8800 systems. https://www.fda.gov/media/136049/download (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Seegene. Allplex™ SARS-CoV-2 Assay, 2022. Detection and identification of 4 target genes for SARS-CoV-2 using multiplex real-time PCR. http://www.seegene.com/upload/images/sars_cov_2/allplex_sars_cov_2_assay_200917.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for South-East Asia, 2017. Use of cell culture in virology for developing countries in the South-East Asia Region. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/258809 (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Renzoni, A.; Pérez, F. F. G.; Nsoga, M. T. N.; Yerly, S.; Boehm, E.; Gayet-Ageron, A.; Kaiser, L.; Schibler, M. Analytical Evaluation of Visby Medical RT-PCR Portable Device for Rapid Detection of SARS-COV-2. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirotsu, Y.; Maejima, M.; Shibusawa, M.; Natori, Y.; Nagakubo, Y.; Hosaka, K.; Sueki, H.; Amemiya, K.; Hayakawa, M.; Mochizuki, H.; Tsutsui, T.; Kakizaki, Y.; Miyashita, Y.; Omata, M. Direct Comparison of Xpert Xpress, FilmArray Respiratory Panel, Lumipulse Antigen Test, and RT-QPCR in 165 Nasopharyngeal Swabs. BMC Infectious Diseases 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. H.; Song, J.-U. Diagnostic Accuracy of the Cepheid Xpert Xpress and the Abbott ID NOW Assay for Rapid Detection of SARS-CoV-2: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Virology 2021, 93, 4523–4531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kogoj, R.; Korva, M.; Knap, N.; Rus, K. R.; Pozvek, P.; Avšič-Županc, T.; Poljak, M. Comparative Evaluation of Six SARS-COV-2 Real-Time RT-PCR Diagnostic Approaches Shows Substantial Genomic Variant–Dependent Intra- and Inter-Test Variability, Poor Interchangeability of Cycle Threshold and Complementary Turn-Around Times. Pathogens 2022, 11, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabaan, A. A.; Tirupathi, R.; Sule, A. A.; Aldali, J. A.; Mutair, A. A.; Alhumaid, S.; Muzaheed; Gupta, N; Koritala, T.; Adhikari, R.; Bilal, M.; Dhawan, M.; Tiwari, R.; Mitra, S.; Emran, T. B.; Dhama, K. Viral Dynamics and Real-Time RT-PCR Ct Values Correlation with Disease Severity in COVID-19. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).