1. Introduction

Climate change is destabilizing the health of our planet and has been recognized as the number one threat to public health around the globe [

1,

2] (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC], 2022). It is estimated that between the years 2030-2050, climate change may cause an additional 250,000 deaths each year [

3] (World Health Organization, 2021a). The IPCC (2022) has called for an urgent reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to mitigate climate change [

1]. Within the Alliance for Transformative Action on Climate and Health (ATACH), the United States (U.S.) is committed to implementing initiatives to develop sustainable, low-carbon, and climate-resilient health systems [

4] (WHO, 2021b). It is critical that healthcare systems work to reduce GHG emissions and develop climate mitigation and adaptation plans to assist the U.S. to honor its commitment to strengthen global climate resilience.

The healthcare industry is responsible for approximately 8.5% of GHG emissions in the United States [

5,

6] (Dzau et al., 2021). Furthermore, the US health sector is a major contributor to global GHG emissions with an emissions per capita rate higher than all other industrialized nations [

7] (Silva et al., 2022). Despite evidence of the healthcare sector’s contributions to climate change, little work has been done to assess consumption-based emissions and understand the grave effects that pollution has on global health [

6,

8] (Eckelman et al., 2016). Measurement of pollution, including GHG emissions, emanating from health care settings is imperative to inform the development of mitigation and adaptation processes [

8,

9] (Eckelman et al., 2016). The global health care sector must decarbonize and become more sustainable to reduce its climate footprint [

6,

8,

10,

11] (Healthcare Without Harm, 2019).

Before this project, the Midwestern Academic Medical Center had not implemented a GHG inventory process, nor had they measured baseline emissions. There were no programs in place to foster sustainability and reduce negative contributions to the environment at the MAMC. The MAMC identified an opportunity to better fulfill the organizational mission to foster longer, healthier lives through environmental stewardship through implementation of this nurse-led initiative.

1.1. Review of Literature

Several frameworks and roadmaps are available to aid healthcare facilities in reducing their carbon footprint. The

Sustainability Roadmap for Hospitals [

12] (American Hospital Association, 2015) and the

Global Road Map for Health Care Decarbonization [

13] (Health Care Without Harm, 2021) provide numerous strategies to develop more sustainable healthcare facilities. Reducing GHG emissions begins with measuring baseline emissions and developing an inventory or tracking process to monitor reduction efforts (Environmental Protection Agency [

14,

15] [EPA], 2020). Resources such as the

Simplified Guide to Greenhouse Gas Management for Organizations [

14] (EPA, 2020), and

The Greenhouse Gas Protocol, Corporate Standard [

14,

16] (Greenhouse Gas Protocol, 2004a) provide background and standards for developing processes to measure and track GHG emissions. These evidence-based tools were integrated into the planning, implementation, and assessment of this quality improvement project.

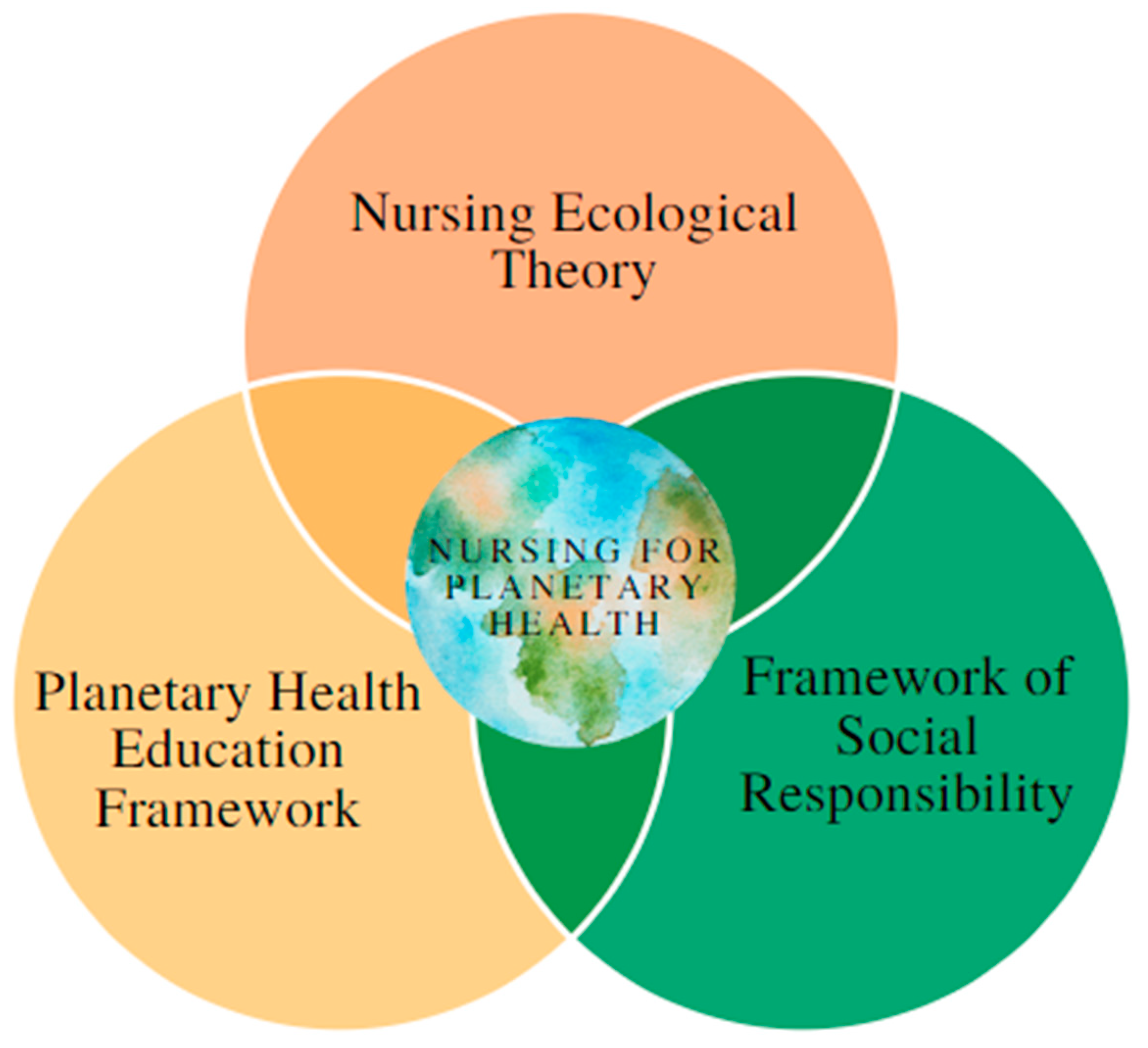

The Nursing Ecological Theory [

17] (Lautsen, 2006), the Ethical Framework of Social Responsibility [

18] (Tyler-Viola et al., 2009), and the Planetary Health Education Framework [

19] (Guzman et al., 2021) were woven throughout this nursing innovation. These theories aligned with the aim of this project, combining theories that focus on nursing, social justice, and planetary health.

Nurses are bound within their Code of Ethics [

20] (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2015) to advocate for policies and activities within the healthcare setting and community to maintain, sustain and repair the natural world. These three frameworks inform this nursing for planetary health quality improvement project. (See

Figure 1)

In addition, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) QI PDSA framework [

21,

22] (2022a) and the Lean Six Sigma (LSS) process improvement framework [

23,

24] (Kubiak & Benbow, 2017) were used to plan and implement this project. The methodological LSS framework uses the DMAIC process: Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, and Control; to guide process improvement and sustainment of QI initiatives. The LSS framework has proven effective in increasing efficiency and improving quality in the healthcare setting [

25] (Ahmed et al., 2013). This QI project represents a smaller project within a larger, LSS Black Belt QI project aimed to reduce GHG emissions.

The goal of this project was to develop a highly effective program to measure and mitigate GHGs produced by the MAMC. The objectives for the project included to measure baseline emissions, develop a standardized process for maintaining a GHG inventory, conduct an energy audit, and provide training on the GHG inventory process to the project team who will be accountable for maintaining the process. This project represented the initial phase of the MAMC’s overarching aim to decrease the organization’s GHG emissions from electrical sources by 10% from baseline by December 2022. The goal was to develop a practical plan to incrementally reduce GHG emissions with the overarching goal beyond the scope of this project being to reduce the inequitable impacts of climate change on patients, employees, and the community.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

The MAMC comprises two large adult hospital campuses and one children’s hospital. The academic medical center is affiliated with a local university and is partially located on the university campus. The medical center is in an urban area of a mid-sized Midwestern city. It is situated amongst low-income communities and serves a diverse population. The MAMC is one unit of a larger healthcare system that includes ten hospitals, and 60 clinics and surgery centers across the state.

2.2. Interventions

Project interventions were developed using current scientific, evidence-based, and reliable expert resources such as the Environmental Protection Agency [

14,

26] (EPA, 2020; EPA, 2021a) and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [

1] (IPCC, 2022). A process was developed to measure Scope 1 and Scope 2 baseline GHG emissions, and measure and track emissions continuously at the MAMC using the EPA’s Lean and Energy Toolkit [

27] (2021b) and the Greenhouse Gas Protocol Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard [

28] (GHG Protocol, 2004a).

After the process was developed, the project director hosted a required, virtual education session to teach the FD staff the process of maintaining the GHG inventory [

28] (GHG Protocol, 2004b). At the end of the project, an energy audit and goal setting were performed in collaboration with the project team and an energy efficiency subject matter expert (SME) to identify and develop goals for reducing emissions. This reduction plan would not have been possible without a way to measure GHGs in place.

2.2.1. GHG Emission Assessment/Measurement

Baseline data was collected, and from this, a directory was developed with emissions sources, data sources, and contact persons for continuous data collection. To provide a quantified annual emission baseline, 2021 was selected as the baseline year from which to compare emissions moving forward and track GHG reduction efforts over time.

2.2.2. Data included:

Electricity, steam, and natural gas data were collected directly from the utility providers in the form of usage statements.

Anesthetic gas data was collected from the MAMC’s Pharmacy Compliance Monitoring and Audit Supervisor.

Refrigerant replacement data was collected from dated invoices showing the type of refrigerant and the volume replaced.

An electronic report of fleet vehicle fuel usage data was shared by the MAMC’s Supply Chain Logistics Specialist.

The EPA’s Simplified Emissions Greenhouse Gas Calculator (SEGHGC) was used as the initial calculation tool to inventory GHG emissions for this project [

14] (EPA, 2020). This Excel spreadsheet tool automatically calculates emissions using built-in formulas and emissions factors. The SEGHCC was modified to be individualized to the MAMC. For example, the SEGHGC template did not include guidance, formulas, or calculations for anesthetic gas. Therefore, MAMC’s individualized GHG inventory was modified to include a worksheet with built-in formulas for calculating emissions from anesthetic gas usage which was developed by the project director and validated by an outside sustainability consultant.

The project director created a 36-page emissions inventory that includes an introduction, summary, boundary guidelines, common conversions, and emissions factors, and twelve pages to track Scope 1, Scope 2, and Scope 3 emissions. Five different sections for sources of Scope 1 and Scope 2 GHG emissions were completed for this project. These include stationary combustion, fleet vehicles, refrigerants, anesthetic gas, electricity, and steam. Each source has its own worksheet and guidelines for completion. Scope 3 emissions are included for future phases of this program.

2.2.3. Education

During the project, the project team which consisted of quality improvement professionals, facilities and engineering professionals, and executive leaders at this health system attended three presentations where the nurse project director provided background and education on planetary health, climate change, and environmental sustainability. One virtual training session was conducted for the accountable FD staff (N=5, 100%) to teach the GHG emissions inventory process. During this two-hour training session, the project director conducted a virtual tour of the shared electronic directory where all data and GHG inventory documents are accessed and stored within the organization. The project director then described and demonstrated the GHG inventory process using teach-back to confirm attendees’ understanding. Time was allowed for attendees to ask clarifying questions and the project director answered questions and provided additional instruction. All attendees completed pre- and post-surveys. Surveys were analyzed to understand and measure the outcomes of the training.

2.2.4. Energy Audit and Goal Development

The project director organized, facilitated, and led an energy audit with the participation of the transdisciplinary project team. An Energy Smart specialist attended the audit and provided guidance and recommendations. This service is offered through the state Chamber of Commerce and is free of charge for organizations that utilize local utility service providers [

29] (Minnesota Chamber of Commerce, n.d.). The audit consisted of two in-person meetings, a tour of the MAMC buildings to identify energy-saving opportunities, a utility bill analysis to understand the facility’s energy usage and patterns, and multiple follow-up discussions through virtual meetings and email. Opportunities for grants and funding assistance were identified during the audit process and short, medium, and long-term goals were developed to reduce emissions.

2.2.5. Measurement of Employee Knowledge.

The eleven-item, pre-intervention survey (Appendix 1) consisted of 10 quantitative and one qualitative item. The survey measured the group’s existing knowledge of GHG accounting, their understanding of GHG scopes, and their feelings and perceptions around environmental sustainability and climate change. A post-intervention survey was conducted, including the same questions as the pre-survey and five additional questions.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

Human subjects’ protection was reviewed using the online Institutional Review Board (IRB) determination tool developed by the University of Minnesota. This project was designated as a Quality Assurance (QA)/QI and did not meet the federal definition of Human Subjects Research. No additional IRB was required for this QI initiative.

3. Results

3.1. GHG Emissions Assessment/Measurement

Greenhouse gas emissions were measured using the associated emissions factor for each emissions source. Emissions were calculated using calculation formulas within the GHG inventory spreadsheet [

14] (EPA, 2020). The MAMC’s individualized GHG inventory was validated by means of a thorough review conducted by an outside sustainability consultant. Emissions were measured using 2021 as the baseline year. Additionally, emissions were calculated for January-October 2022 for comparison (see

Table 1).

3.2. Education

A total of five (N=5) project team members received the GHG inventory education intervention and completed both the pre- and post-presentation surveys. The participants included in the training will be directly accountable for maintaining the GHG inventory process at the MAMC with the nurse Project Director as a resource.

3.3. Data Analysis

Survey data were obtained using an electronic survey which was distributed by QR code and hyperlink. The nurse Project Director entered survey data into an Excel spreadsheet and conducted scoring of qualitative and quantitative data. Qualitative responses were tracked in an Excel spreadsheet and summarized in descriptive statistics such as percentages in

Table 2 and

Table 3.

3.4. Pre-Intervention

The pre-intervention survey occurred two weeks prior to the GHG inventory process virtual training. Survey items 1-11 were the same for the pre- and post- surveys (see

Table 4). Of the training group, 50% (

n=2) were able to accurately select the sources of Scope 1 emissions from the multiple-choice options. Scope 2 emissions sources were correctly identified by 75% (

n=3) of the group. Seventy-five percent (

n=2) of the training group correctly identified Scope 3 emissions sources. One hundred percent (

N=4) of the group rated their level of experience with GHG accounting as a

beginner. Attendees were asked, “From your perspective, how important is it that the MAMC strives to reduce GHG emissions?” Fifty percent (

n=2) answered

extremely important, 25% (

n=1) answered

somewhat important, and 25% (

n=1) answered

extremely not important.

The training group was asked, “What are the organizational barriers to developing and maintaining a GHG inventory?” to which one stated "Manpower and high regulatory standards make change difficult,” and another stated, “We need a sustainability expert to guide this work. We currently don't have this.” One hundred percent of the group selected true from the multiple-choice options: true, false, or not sure when asked if GHG emissions contribute to climate change and negatively impact human health.

Developing a sustainability program at the MAMC was identified as important by 100% (N=5) of the training group. Lastly, the group was asked to rate how they feel about learning about GHG emissions and having the GHG emissions inventory process as part of their work, 40% (n=2) reported that they were indifferent while 60% (n=3) reported that they felt excited.

3.5. Post-Intervention

The post-intervention survey was conducted after the GHG inventory training intervention. Items 12-16 were included on the pose-intervention survey only (see Table 5). The survey was sent immediately after the training and attendees were given one week to complete the survey. Twenty percent (n=1) of the training group rated their knowledge about GHG emissions as very little while 80% (n=4) rated their knowledge as moderate. The group was asked to rate their experience with GHG accounting and maintaining a GHG inventory, 80% (n=4) self-identified their level of experience as a beginner, and 20% (n=1) identified their level of experience as moderate. Forty percent (n=2) felt that it is extremely important that the MAMC maintain an inventory of GHG emissions while 60% (n=3) felt that it is somewhat important. Attendees were asked to select true, false, or unsure when asked if GHG emissions contribute to climate change which negatively impacts human health and 100% of the training group answered that this is true.

The additional post-survey items aimed to measure the effectiveness of the training in preparing the group to maintain the GHG inventory process. The group was asked to rate their readiness to maintain the GHG inventory process after receiving training; 80% (n=4) felt confident while 20% (n=1) did not feel confident. When asked “How prepared do you feel to teach the GHG inventory process to others,” 20% (n=1) felt unprepared while 80% (n=4) felt prepared. One hundred percent of the group was able to identify two methods to reduce GHG emissions at the MAMC after attending the training (see Table 6).Finally, the training group was asked how their understanding of the links between GHG emissions, climate change, and human health has changed after their participation in this project and the associated training, 40% (n=2) said that their understanding has grown a little and 60% (n=3) said that their understanding has grown a lot.

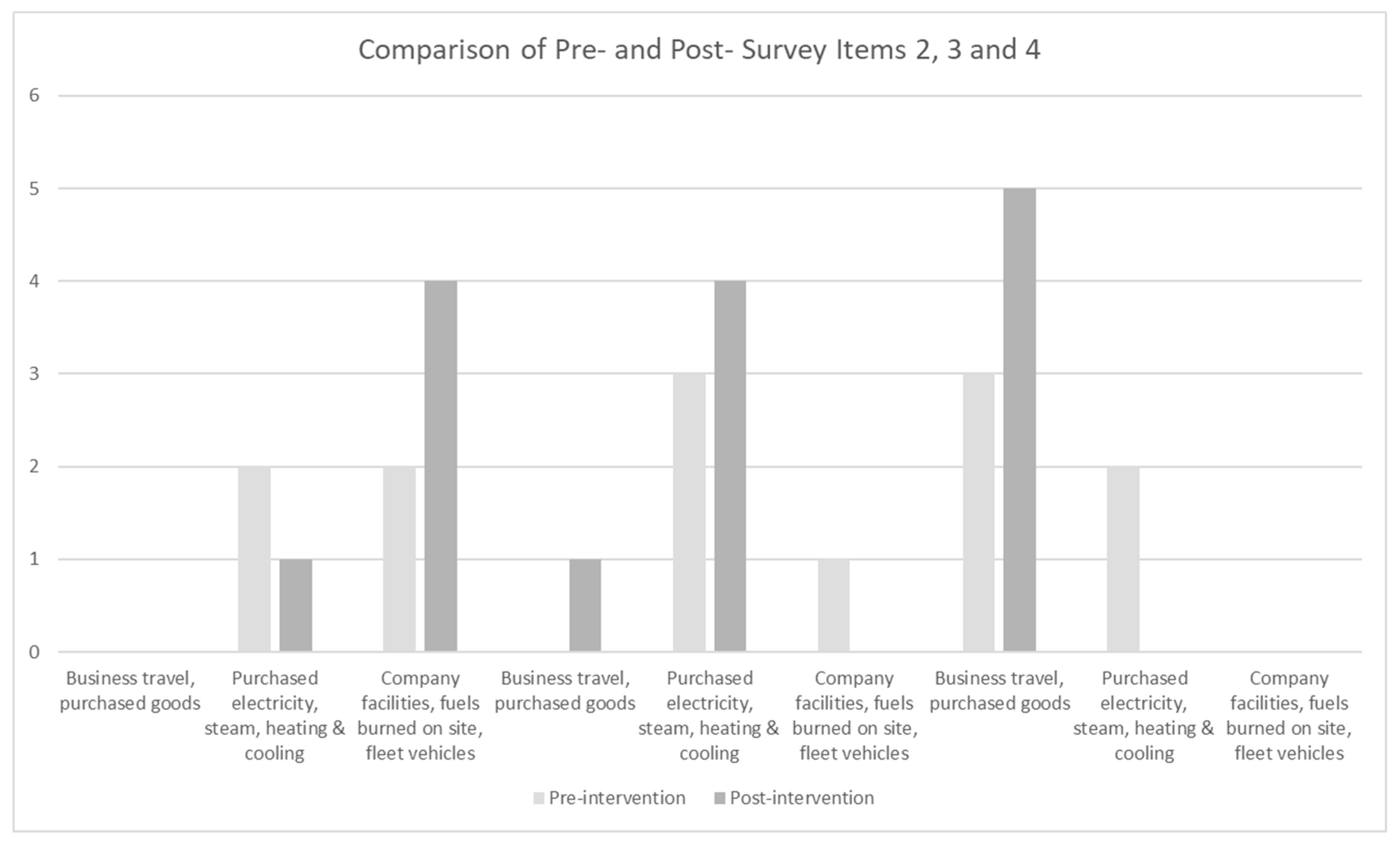

3.6. Pre-Post-Intervention Comparison

Comparing pre-post-survey results, 100% (N=5) of the group identified barriers to developing and maintaining a GHG inventory pre-intervention, while 40% (n=2) felt there were no barriers to this after attending the training. The training group was asked to identify the sources of Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions (see figure 2). Scope 1 emissions include company facilities, fuels burned on site, and fleet vehicles. Scope 2 emissions include purchased electricity, steam, heating, and cooling. Scope 3 emissions include business travel, purchased goods, and services. 80% (n=4) were able to correctly identify the sources of Scope 1 and 2 emissions, and 100% (N=5) were able to correctly identify the sources of Scope 3 emissions after the training.

Figure 2.

Comparison of Pre- and Post-Survey Responses.

Figure 2.

Comparison of Pre- and Post-Survey Responses.

Survey item 6 shows a shift in the project team’s perspective regarding the importance of monitoring GHG emissions at the MAMC (see

Table 3). Pre-survey results showed that 60% (

n=2) felt that it was extremely important, 20% (

n=1) felt that it was somewhat important, and 20% (

n=1) felt that it was extremely not important to monitor GHG emissions at the MAMC. In contrast, the post-survey findings showed that 40% (

n=2) felt that it was extremely important and 60% (

n=3) felt that it was somewhat important to monitor GHG emissions at the MAMC. While one team member shifted from feeling that it is extremely important to somewhat important to monitor GHG emissions, the post-survey results showed that through this initiative all project team members were convinced that it is at least somewhat important to monitor GHG emissions at the MAMC.

Similarly, there was a shift in the perspective of team members on survey item 7 (see

Table 3). The pre-survey results showed that 50% (

n=2) felt that it is extremely important, 25% (

n=1) felt that it is somewhat important, and 25% (

n=1) felt that it is extremely not important to strive to reduce GHG emissions at the MAMC. Post-survey results showed that 40% (n=2) felt that it is extremely important and 60% (

n=3) felt that it is somewhat important to strive to reduce GHG emissions. While the N size differed between the pre-post-survey for this question, one team members perspective changed from extremely not important to somewhat important to strive to reduce GHG emissions because of this project.

3.7. Limitations

There are some notable limitations of this QI project. First, the sample size is not large enough to be a representative sample. This project was designed as a QI pilot for the MAMC site within a large health system and so the accountable team of staff at the specific site was only five employees. Second, this QI project represents the first phase of a large-scale project aimed to reduce GHG emissions and so the efficacy of the GHG inventory cannot totally be measured at this stage of the project.

The virtual training platform used for the education intervention introduced some limitations such as the opportunity for attendees to practice data entry into the GHG inventory in real time. To remove some of these limitations the project should be expanded across sites, involve more participants, and the length of the project should be extended to measure reductions in GHG emissions over time.

4. Discussion

The overarching goal of this project was to influence one healthcare system to prepare and adapt to the current and coming effects of climate change through a nurse lead initiative. This project has laid the groundwork for further climate resiliency initiatives at the MAMC. Though there are barriers that the MAMC must overcome to be successful and urgently reduce its environmental footprint. Through interviews with the project team and qualitative data analysis it is evident that a lack of time and designated staff and leadership are barriers to embedding environmental sustainability into the core mission of this health system.

A step by step, standardized procedure to track GHG emissions was developed during this QI project and has been implemented at the MAMC. The MAMC is in the process of integrating the procedure document into the electronic policy database to be available to all employee’s system wide. The MAMC has committed to implementing this procedure across the other ten hospitals in the health system, though training and assigning accountable staff to do the work is yet to come. As part of the overarching QI project, statistical analysis of emissions data and carbon reduction strategies was performed. The MAMC has been presented with a practical plan to reduce emissions. By investing about $500,000 to implement a combination of improvement methods such as wind sourced energy, solar power and LED lighting, the MAMC can reduce their GHG emissions by 2133 MT of CO2e per year, have substantial yearly cost savings and save an estimated 3.5 million dollars over 30 years.

Executive leaders and the accountable FD staff were presented with the results of this statistical analysis and predictive modeling. The organization made a commitment through executive sponsorship of this LSS Black Belt project to implement some improvement measures. The project owner is in the process of developing an implementation plan and leading continued discussions to determine the improvement methods that will be approved for implementation by the project's executive sponsor. Next steps are to implement improvements, continue to collect and analyze data, measure success of the improvement methods and develop and implement a control plan.

Unexpected but propitious outcomes were the high-level of engagement and interest of employees across the organization seeking to learn more about this project and the status of climate readiness at the MAMC. A movement has developed and employees from across disciplines are seeking knowledge about the organization's limited portfolio of environmental sustainability initiatives. Employees and community members are expressing curiosity about how climate action and environmental stewardship can be integrated into the health systems core mission, vision, and values in a tangible way.

5. Conclusions

The MAMC and its encompassing health system have many strengths such as their partnership with the local university and highly engaged staff and community members, who have the potential to aid in promoting climate mitigation and adaptation throughout the organization. To maximize these strengths to their fullest potential, the health system must undergo systems change to transform its culture into one that adopts a deep social responsibility to care for global ecosystems and educates and calls all stakeholders to address climate change. For healthcare organizations to shift their culture and make the most impact in reducing their environmental footprint to mitigate and adapt to climate change and safeguard the health of life on earth, it will be essential to understand and integrate the key concepts, theories, and frameworks presented in this manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges Paul Hodges, Director or Quality Improvement, M Health Fairview.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate change 2022: Mitigation of climate change. 2022. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/.

- Balbus, J. , Frumpkin, H., Hess, J., McGeehin, M., & Sheats, N. National climate assessment: Health. U.S. Global Change Research Program, 2014; https://nca2014.globalchange.gov/report/sectors/humanhealth#intro-section-2. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. COP26 special report on climate change and health: the health argument for climate action. 2021a. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240036727. 9789.

- World Health Organization. Alliance for transformative action on climate and health. 2021b. https://www.who.int/initiatives/alliance-for-transformative-action-on-climate-and-health/cop26-healthprogramme.

- Dzau, V. J. , Levine, R., Barrett, G., & Witty, A. Decarbonizing the U.S. health sector - A call to action. The New England journal of medicine, 2021; 385, 2117–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwis, A. , & Limaye, S. The costs of inaction: The economic burden of fossil fuels and climate change on health in the United States. The Medical Society Consortium on Climate & Health; Natural Resources Defense Council, 2021; https://www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/costs-inaction-burden-health-report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, L. , Wood, M., Johnson, B., Coughlan, M., Brinton, H., McGuire, K., Brigdham, S. A generalizable framework for enhanced natural climate solutions. Plant Soil 2022, 479, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckelman, M. J. , & Sherman, J. Environmental impacts of the U.S. health care system and effects on public health. Environmental impacts of the U.S. health care system and effects on public health. PloS one 2016, 11(6), e0157014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennison, I. , Roschnik, S., Ashby, B., Boyd, R., Hamilton, I., Oreszczyn, T., Owen, A., Romanello, M., Ruyssevelt, P., Sherman, J., Smith, A., Steele, K., Watts, N., Eckelman, M. Health care’s response to climate change: a carbon footprint assessment of NHS in England. The Lancet Planetary Health 2021, 5(2), E84-E92, 2542. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Healthcare Without Harm. Health care’s climate footprint: How the health sector contributes to the global climate crisis and opportunities for action. Green paper number one, 2019; https://noharmglobal.org/sites/default/files/documents files/5961/HealthCaresClimateFootprint_092319.pdf.

- Salas, R. N. , Maibach, E., Pencheon, D., Watts, N., & Frumkin, H. A pathway to net zero emissions for healthcare. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 2020; 371, m3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Hospital Association. Sustainability roadmap for hospitals: A guide to achieving your sustainability goals. 2015. http://www.sustainabilityroadmap.org/about/briefguide.shtml#.Y4QT8VrMKUk.

- Healthcare Without Harm. Global roadmap for healthcare decarbonization. 2021. https://healthcareclimateaction.org/sites/default/files/2021-04/HCWH%20Road%20Map%20for%20Health%20Care%20Decarbonization%20-%20Introduction.pdf.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Guide to greenhouse gas management for small business and low emitters. 2020. Guide to Greenhouse Gas Management for Small Business & Low Emitters (epa.gov).

- Practice Green Health. Addressing climate change in the health care setting: Opportunities for action.(n.d). https://practicegreenhealth.org/sites/default/files/pubs/epp/ClimateChange.pdf.

- Greenhouse Gas Protocol. The greenhouse gas protocol: A corporate accounting and reporting standard. 2004a. https://ghgprotocol.org/sites/default/files/standards/ghg-protocol-revised.pdf.

- Laustsen, Gary. Environment, ecosystems, and ecological behavior: A dialogue toward developing nursing ecological theory. Advances in Nursing Science, 2006 29; 43–54.

- Tyer-Viola, L. , Nicholas, P., Corless, I., Barry, D., Hoyt, P., Fitzpatrick, J., & Davis, S. Social responsibility of nursing: A global perspective. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice, 2009; 10, 110–118. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán, C. , Aguirre, A., Astle, B., Barros, E., Bayles, B., Chimbari, M., El-Abbadi, N., Evert, J., Hackett, F., Howard, C., Jennings, J., Krzyzek, A., LeClair, J., Maric, F., Martin, O., Osano, O., Patz, J., Potter, T., Redvers, N., Trienekens, N., … Zylstra, M. The Planetary health education framework. The Planetary Health Alliance, 2011; https://www.planetaryhealthalliance.org/education-framework. [Google Scholar]

- 20. American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements, American Nurses Publishing.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Plan-do-study-act (PDSA) worksheet. 2022a. https://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/PlanDoStudyActWorksheet.aspx.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. The IHI Triple Aim. 2022b. https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx.

- Mortimer, F. , Isherwood, J., Wilkinson, A., & Vaux, E. Sustainability in quality improvement: Redefining value. Future healthcare journal 2018, 5(2), 88–93. [CrossRef]

- Kubiak, T. , Benbow, D. The certified six sigma black belt handbook third edition. American Association for Quality, Quality Press. 2017.

- Ahmed, S. , Manaf, N. H., & Islam, R. Effects of lean six sigma application in healthcare services: a literature review. Reviews on environmental health, 2013; 28, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Climate change and social vulnerability in the United States: A focus on six impacts. 2021a. https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2021-09/climate-vulnerability_september-2021_508.pdf.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Lean and Energy Toolkit. 2021b. Lean & Energy Toolkit: Contents & Acknowledgements | US EPA.

- 28. Greenhouse Gas Protocol. Managing inventory quality. In the greenhouse gas protocol: A corporate accounting and reporting standard, 2004; 48–57, https://ghgprotocol.org/sites/default/files/standards/ghg-protocolrevised.pdf.

- Minnesota Chamber of Commerce.Energy smart. https://www.mnchamber.com/your-opportunity/energysmart.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).