1. Introduction

For millennia, humanity has drawn upon environmental resources to ensure survival and well-being. Even in contemporary times, plants remain invaluable sources of sustenance and medicinal properties [

1,

2]. Nevertheless, a scarcity of ethnobotanical and chemical investigations has obscured the full extent of their pharmacopoeia, nutritional value, and therapeutic potential.

In the present era, uncovering the botanical intricacies and therapeutic merits of plants presents a formidable challenge. Indeed, plants are fundamental and essential components in pharmaceutical research and production [

1]. Consequently, delving into their chemical compositions and nutritional profiles emerges as a critical pursuit to enhance their application in medicine. Notably, plant-based derivatives constitute over 50% of the global medicinal repertoire [

3]. These plants are frequently encountered in herbalists' domains, traditional healing practices, marketplaces, or their regions of origin. The leaves, barks, roots, and fruits of medicinal plants constitute the most utilized components for phytotherapeutic purposes, often administered through maceration, infusion, digestion, or decoction [

4].

The Cucurbitaceae family, widely employed in traditional medicine, encompasses herbaceous vines with tendrils, and in some cases, shrubs. Certain of these species exhibit widespread distribution across tropical and subtropical regions [

4,

5]. Cucurbits notably hold a significant position in Africa, offering a range of edibles (such as squash, pumpkin, melon) and utilitarian items (like gourds and sponges). The fruits of numerous cucurbit species, rich in micronutrients, constitute dietary staples in Africa, sometimes consumed as juices to alleviate micronutrient deficiencies. Plants within the

Momordica genus are of notable importance for their remedial attributes [

6].

Momordica balsamina, commonly known as balsam apple or referred to as Mburbuf or Mborbof in the Wolof language (native to Senegal), belongs to the

Momordica genus. Flourishing in arid expanses of tropical and subtropical Africa,

Momordica balsamina serves a dual role, being both a dietary staple and a fundamental element of traditional African medicine. It finds application in alleviating diverse symptomatic manifestations, including these associated with diabetes and malaria [

7].

The primary objective of this article is to provide a comprehensive botanical delineation of Momordica balsamina, followed by an exhaustive exploration of its numerous applications. Subsequently, a detailed synthesis of its chemical composition, biological activities, and nutritional potential is presented.

Momordica balsamina, with its numerous applications in the food sector, as a source of medicine, and potentially as a source for new cosmetic ingredients, truly deserve this review paper.

2. Botanical Description of Momordica balsamina

The genus

Momordica comprises approximately fifty-nine herbaceous or perennial herbaceous species, occasionally manifesting as small shrub climbers. These plants belong to the cucurbit family and are indigenous to tropical and subtropical regions of Africa, Asia, and Australia [

8].

Momordica balsamina (

Figure 1) is an annual herbaceous, monoecious, climbing plant with glabrous or lightly hairy stems up to 4 to 5 m long, equipped with tendrils for attachment to nearby vegetation. It grows at altitudes of 0 to 1,293 m [

3,

4,

9].

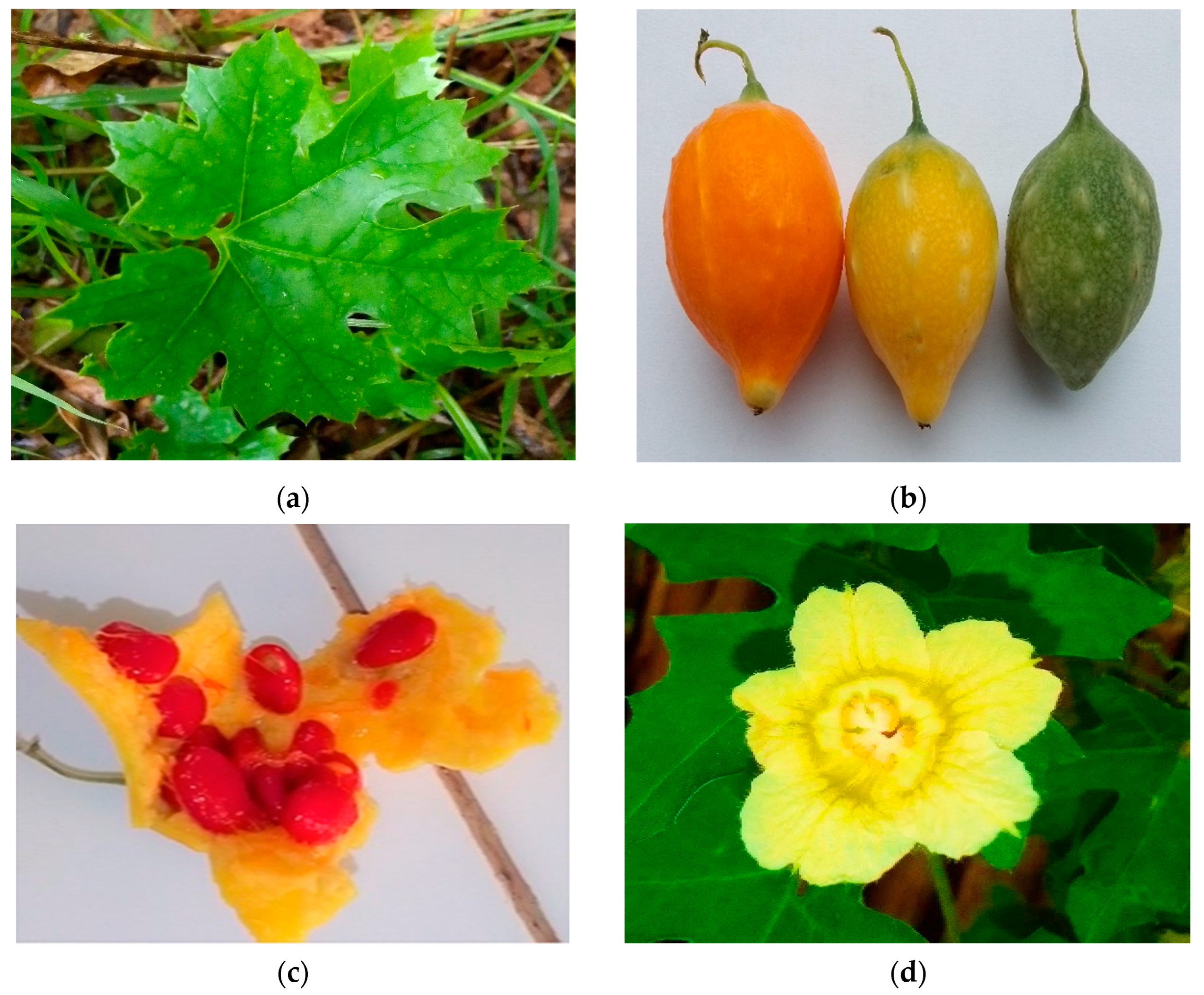

The leaves of

Momordica balsamina (see

Figure 1a) exhibit a light green hue. They are alternate, waxy, simple, and lobed, featuring three to five distinct lobes covering up to half of the leaf blade. These leaves can reach a length of 12cm [

4,

9,

10];

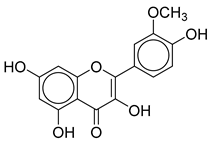

The flowers (see

Figure 1d) are pale yellow, monoecious, and solitary. They take on a rounded, trumpet-like form, characterized by a pedicel measuring up to 0.5 cm in length. The receptacle spans 0.5-1 mm, while the sepals are narrow and can grow up to 0.5 cm. Petals range from 0.5-1.5 cm in length, surrounding a unicellular lower ovary [

3,

4,

10],

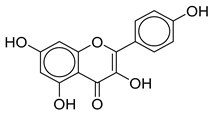

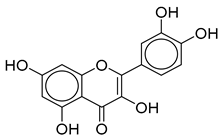

The fruits of

Momordica balsamina (see

Figure 1b) adopt a spindle-shaped appearance, with colors shifting from orange to vibrant red. These fruits exhibit about 19 rows of regular or irregular, short, blunt, non-prickly, creamy, or yellowish spines. Upon ripening (when orange), the fruits, which measure 25-60 mm, spontaneously split into three coiled valves, revealing numerous seeds enshrouded by a vivid, extremely adhesive scarlet aril. This aril is edible and possesses a sweetness akin to watermelon. The seeds are encased within a crimson pulp. Oval and compressed, the seeds span 9 to 12 mm in length [

3,

4,

10].

Momordica balsamina is a prevalent vegetable within tropical and subtropical zones [

6]. Originating in tropical Africa, it has proliferated across drier areas of South Africa and coastal regions of Australia. Its cultivation has extended to European gardens, as well as central American, Arabian, tropical Asian, and Indian regions. In India, it thrives naturally in forests during the rainy season. This species has been introduced to parts of the Neotropics, gaining naturalization in the United States and Pakistan [

9,

11]. It is found growing in the wild across southern African regions, including Botswana, Swaziland, Namibia, and South Africa. Within South Africa, it flourishes in the Eastern and Northern Cape, Limbo, and Kwazulu-Natal provinces [

3].

3. Traditional Uses of Momordica balsamina

Momordica balsamina is an intriguing plant renowned for its potent medicinal properties. It finds application in treating a variety of conditions such as hypertension, digestive disorders, malaria, diabetes, and measles prevention [

4].

Furthermore, Momordica balsamina is recommended for addressing dermatological ailments like pimples, skin spots, and edema. It serves as a remedy for wounds, eczema, allergies, and skin infections, while also functioning as a skin moisturizer.

The plant assumes the role of an anthelmintic when employing its fruits, seeds, and leaves. Leaves are used to combat fever and excessive uterine bleeding, while the whole plant is utilized to manage syphilis, rheumatism, hepatitis, and diverse skin conditions. It has applications as an abortifacient, aphrodisiac, galactogen, and diabetic treatment [

4,

12]. Diabetic patients consume leaf decoctions orally to regulate blood sugar levels. The plant is employed in various forms such as infusions, poultices, and herbal teas to address issues like liver problems, stomach cramps, and ulcers [

4].

The utilization of

Momordica balsamina in traditional medicine is both diverse and extensive, spanning various countries and cultures. This plant has found its way into the pharmacopeias of different regions, where its different parts are harnessed to address a multitude of health concerns. Below is an overview of its traditional medicinal applications: (refer to

Table 1).

In Senegal, it is employed for treating dermatosis, stomachaches, rheumatism, hemorrhoids, painful menstruation, and other ailments. An aqueous extract of its leaves alleviates menstrual discomfort in young girls. It also finds utility in malaria and diabetes treatment through methods such as decoction, or infusion. The Wolof people (Senegal) utilize the fruits for purgative and deworming purposes [

2,

3]. In Nigeria, it addresses asthenia and digestive issues, while the Fulani people use it as a deworming agent and tranquilizer [

13]. It is even integrated into prescriptions for mental health concerns. Additionally, a maceration of the entire plant acts as a galactagogue and is employed for chest massages to alleviate intercostal pain [

3].

In Togo, a decoction of

Momordica balsamina's aerial parts, along with honey and Zanthoxyloides fagara root bark, functions as an oxytocic agent. Togolese people frequently utilize the leaves and stems [

13]. Oral administration of calcined aerial parts powder is employed to treat hernias [

13].

In different regions, the plant's fruits and leaves are used as hemostatic antiseptics for wound treatment. In Zambia, a decoction of the entire plant is used to treat conditions like syphilis, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). The compound "Momordin" derived from the plant exhibits inhibitory properties against HIV and other viruses [

3].

In Niger, crushed

Momordica balsamina leaves are used as poultices for skin infections. Pounded leaves are recommended for hemorrhoids, diabetes, and fever. In combination with Combretum micrantthum, it's utilized to treat malaria. Some women mix it with henna for abortion. The Hausa people (Mali) use the whole plant for embalming, drinking, and bathing to ward off malevolent spirits [

13].

In Indonesia, bitter melon is not only known as a vegetable; it is also traditionally used as a laxative, a fever remedy, and an appetite stimulant. Additionally, bitter melon leaves are used to alleviate menstrual discomfort, heal burns, treat skin diseases, and act as a vermifuge [

14].

4. Biological properties of Momordica balsamina

Momordica balsamina leaves are employed as a vegetable, consumed as a decoction, or incorporated into various recipes in conjunction with other plants [

15]. The leaves, fruits, seeds, and bark of this plant offer substantial medicinal benefits, including anti-HIV, anti-plasmodial, anti-diarrheal, antiseptic, antibacterial, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, hypoglycemic, antioxidant, analgesic, and hepato-protective properties [

3,

16,

17].

The plant

Momordica balsamina exhibits highly interesting

in vitro and

in vivo antiplasmodial activities with very low toxicity. This could potentially explain its widespread use in traditional malaria treatment in Niger [

18].

The antibacterial activity of this plant was investigated by Jigam et al. (2004) [

19]. They reported that methanol (MeOH) extracts of various parts of the

Momordica balsamina plant exhibited activity against

Staphylococcus aureus and

Escherichia coli. This finding aligns with the research conducted by Otimenyin et al. (2008) [

20], who also demonstrated activity against

Bacillus subtilis,

Proteus mirabilis, and

Klebsiella pneumoniae using extracts from the same plant.

Crude

Momordica balsamina extracts also hold significant potential as antimicrobial agents and can be employed in the treatment of infectious diseases. These extracts have showcased the antibacterial and hypoglycemic properties, which may elucidate the plant's traditional use in managing diabetic sores [

20].

Momordica balsamina extracts have been found to significantly inhibit the growth of Bacillus subtilis, Streptococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhi, Proteus vulgaris, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa to varying degrees [

21].

The

Momordica balsamina plant has demonstrated anti-HIV properties. Specifically, the plant protein MoMo30, isolated from

Momordica balsamina, has been found to effectively inhibit HIV-1 at nanomolar levels while exhibiting minimal cellular toxicity at inhibitory levels [

22], which agrees with the work of Coleman et al. (2022) [

23].

Khumalo et al (2023) demonstrated that oral administration of

Momordica balsamina to pre-diabetic rats attenuated diabetes-associated renal function abnormalities by reducing damage and restoring renal function. [

24,

25].

Kgopa et al. (2020) [

26], uncovered that both the relatively non-polar extracts from

Momordica balsamina fruits, such as hexane and ethyl acetate extracts, have the ability to increase glucose uptake by RIN-m5F β-cells, and this effect is dependent on the dosage of the extract.

Ampitan et al. (2023) [

27], demonstrated the effectiveness of

Momordica balsamina extract against avian paramyxovirus-1 infection in broiler chickens.

The results of research of A.T. Samaila's [

28], reveal that

Momordica balsamina leaf and root extracts have the potential to generate drugs and compounds with antifungal properties, effectively targeting pathogenic fungi.

5. Cosmetic use

In the realm of cosmetics,

Momordica balsamina finds extensive application in addressing dermatological concerns. Notably, the juice extracted from the leaves of

Momordica balsamina has been employed as a natural soap [

12]. This unique formulation, often referred to as "pimples natural soap," harnesses the properties of

Momordica balsamina to combat pimples, skin spots, and edema. When mixed with water, it produces a mildly soapy solution. The plant's soothing attributes extend to the treatment of wounds, eczema, pimples, allergies, and skin infections. Additionally,

Momordica balsamina serves as a highly effective skin moisturizer [

10,

12].

6. Other Uses of Momordica balsamina

The versatility of the

Momordica balsamina plant transcends beyond therapy and encompasses various other domains: The whole plant extract demonstrates insecticidal properties, making it a valuable tool in pest control. The seeds of the plant are often utilized as arrow poison. The plant contributes to mitigating micronutrient deficiencies within the soil, aiding in soil health and fertility enhancement [

3]. Extracts from the leaves of

Momordica balsamina serve as effective metal cleaners [

12]. Additionally, the ethanolic extract of

Momordica balsamina leaves has been studied for its potential to safeguard copper from corrosion within acidic environments [

29]. In the Hausa regions of Nigeria and the Niger Republic, the leaves are incorporated into green vegetable soups consumed by nursing mothers. It is believed that these soups aid in post-labor blood regeneration and the purification of breast milk [

30]. Among farmers, the plant is harnessed to augment milk production in cows [

13]. The multifaceted applications of

Momordica balsamina highlight its valuable contributions across diverse sectors, ranging from cosmetics, therapy to agriculture and beyond.

7. Chemical Composition of Momordica balsamina

Momordica balsamina is revered in traditional medicine for its diverse chemical composition, contributing to its efficacy in treating a multitude of diseases. Each part of the plant is utilized in accordance with its distinct chemical compositionand the specific ailment to be addressed.

The plant's leaves, fruits, stems, seeds, and bark collectively contain a spectrum of compounds, including resins, alkaloids, flavonoids, glycosides, steroids, terpenes, cardiac glycosides, and saponins, among others (refer to

Table 2). The fruit of

Momordica balsamina notably boasts a significant quantity of saponins, steroid rings, and carbohydrates. Alkaloids, tannins, flavonoids, glycosides, steroids, and terpenes are also present, albeit in smaller amounts [

2,

31,

32,

33]. Furthermore, aerial parts of the plant encompass mucilage and reducing compounds [

31].

Based on findings from ethnopharmacology surveys, phytochemical screenings, and extract fractionation through chromatography, a range of biological tests can be conducted. These include assessments of antioxidant, antibacterial, antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory, antimalarial, antiviral, and anti-HIV properties, among others [

34,

35,

36,

37]. The observed biological activities can be attributed to the presence of identified or isolated metabolites within

Momordica balsamina extracts, including flavonoids, terpenes, phenolic acids, carotenoids, and more (refer to

Table 3).

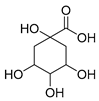

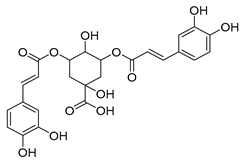

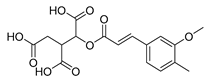

Numerous phenolic acids, such as quinic acid and various chlorogenic acids, have been identified within the plant [

35,

36]. Unique compounds, including pseudolaroside A acid and isocitric feruloyl acid, have been reported for the first time in relation to

Momordica balsamina [

29]. Common flavonoids, including kaempferol, quercetin, and isorhamnetin, have been identified, each exhibiting distinct glycoside forms [

35,

36]. Notably, certain flavonoids demonstrate an array of biological activities, such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antidiabetic effects [

35,

36].

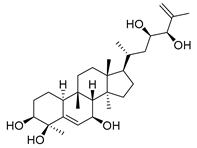

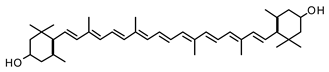

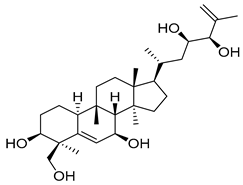

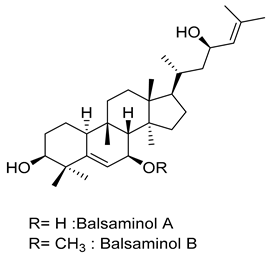

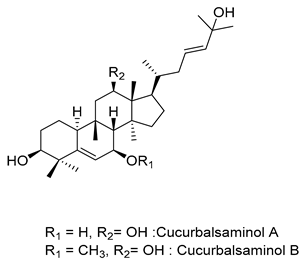

Cucurbitane triterpenoids, encompassing balsaminols, balsaminosides, balsaminagenins, karavilagenins, and cucurbalsaminols, have been extensively investigated for their diverse bioactivities, including antidiabetic, antimalarial, antiplasmodial, anticancer, antibacterial, and P-gp inhibitory effects [

37]. Carotenoids, including zeaxanthin, lutein, and β-carotene, renowned for their antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, and anti-aging properties, have also been identified within the plant [

36].

It exerts ribosomal inactivation (RIP) [

11], and allows inhibition of HIV-1 replication at the translation stage [

11,

38]. Moreover, a broad-spectrum antibacterial activity has been documented [

37].

This rich chemical profile contributes to the plant's versatility and potent therapeutic properties, making it a valuable resource in traditional medicine and beyond.

8. Nutritional Value

Momordica balsamina stands as a plant rich in vital micronutrients and holds a significant place in African cuisine [

39]. The leaves of

Momordica balsamina, deemed a significant green leaf vegetable, possess a multifaceted nutritional potential. It offers a source of nutrients that complements major dietary components [

9].

Table 4 highlights the micronutrient composition, encompassing protein, fiber, fat, minerals, and caloric value of

Momordica balsamina. Notably, the protein content of this wild vegetable is remarkably high (287.7 ± 1.8 g/Kg or 28.77%), surpassing that of numerous other vegetables [

9]. This elevated protein content positions it as a promising protein supplement or meat substitute, especially for resource-scarce rural communities [

9]. In line with recommended daily protein allowances, a mere 3g of

Momordica balsamina leaves could significantly contribute to daily protein requirements.

With its relatively low crude fiber content (37.2 ±7.9),

Momordica balsamina leaves contribute substantially to dietary fiber intake, an essential component in human nutrition [

9]. Characteristic of most green leafy vegetables,

Momordica balsamina boasts a modest caloric value (1892.2 kcal/kg), making it a favorable dietary addition for those aiming to manage caloric intake [

30]

Impressively high ash content (12.7 ±17.0 g/100g) establishes

Momordica balsamina as a dependable source of essential minerals [

9]. Notably, potassium and calcium dominate the mineral composition (27.05 and 22.2 g/kg, respectively). Even a modest consumption of 4g for children and 6g for adults of

Momordica balsamina can fulfill a part of daily calcium needs, alongside potassium requirements ranging from 1.5g to 17g [

9]. The elevated potassium content suggests its potential as a dietary addition to mitigate hypertension, stroke, cardiac disorders, kidney damage, and osteoporosis, particularly in conjunction with low sodium diets [

9]. In contrast, the levels of sodium, magnesium, zinc, and iron remain relatively low, underscoring the need for alternative sources for these micronutrients.

While

Momordica balsamina leaves are found to be low in vegetable lipids, aligning with the characteristic low-fat nature of leafy greens, the results substantiate its role in promoting health and preventing obesity [

30].

Table 5 delves into the amino acid composition of

Momordica balsamina, revealing a preponderance of non-essential amino acids, primarily glutamic acid and aspartic acid, comprising 12, 38, and 8.21 mg/100g of protein, respectively [

30]. However, it is noteworthy that while these proteins, including balsamin, are rich in certain amino acids, their profile lacks balanced proportions of the eight essential amino acids, including isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, valine, and histidine.

The nutritional richness of Momordica balsamina establishes its potential as a pivotal dietary component, contributing to dietary diversity, health management, and nutrient supplementation for various populations.

Nutritional data for

Momordica balsamina fruits reveals that they are among the most diverse and promising vegetable crops for inclusion in the human diet [

40].

9. Conclusions

In summary, this review underscores the extensive utilization of Momordica balsamina within traditional African medicine. The breadth of its traditional applications finds validation in its diverse array of biological properties and intricate chemical compositions. Consequently, we advocate for the incorporation of Momordica balsamina in phytotherapeutic practices. It is imperative, however, to acknowledge the potential toxicity associated with many plants employed in traditional medicine, and therefore, meticulous attention must be dedicated to ensuring proper usage, adherence to prescribed doses, and mitigation of potential toxic effects. Simultaneously, it becomes essential to safeguard a sustainable and ample reservoir of active compounds, thereby averting the depletion of vital natural resources. In this context, comprehensive investigations into the innovative methodologies and strategies for the synthesis or biosynthesis of these naturally occurring bioactive constituents.

Overall, Momordica balsamina's nutritional richness suggests a pivotal role in enhancing dietary diversity, managing health, and supplementing nutrients across populations. Momordica balsamina, rich in vital micronutrients, holds significance in African cuisine as a versatile plant. Its leaves, a valuable green vegetable, offer high protein content making it a potential protein supplement, particularly for resource-scarce communities. With considerable dietary fiber and modest caloric value, it aids nutritional intake and suits calorie management.

Furthermore, given its prevalent application in addressing dermatological concerns, particularly in Senegal, there exists a compelling rationale to embark on comprehensive studies exploring its potential within the cosmetic sphere. As the intricate interplay between tradition, science, and sustainability unfolds, embracing the multifaceted potentials of Momordica balsamina beckons us toward a realm of holistic health and well-being.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization by M.T., I.S. and M.-L.F.; Methodology M.T.; Investiga-tion I. S., M.-L.F., Writing and original draft preparation M.T., Writing, Review & Editing I.S., M.-L.F., M.L.G. and M.G., Project Administration I.S. and M.-L.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Center for Partnership and Development Cooperation (PACODEL), the Academy of Research and Higher Education (ARES) and the University of Liége (ULiège).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rikisahedew, J.J.; Naidoo, Y. Phyto-histochemical evaluation and characterization of the foliar structures of Tagetes minuta L. (Asteraceae). S. Afr. J. Bot. 2018, 115, 328–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balde, S.; Ayessou, N.C.; Gueye, M.; Ndiaye, B.; Sow, A.; Cissé, O.I.K.; Cissé, M.; Diop, C.G. Ethnobotanical investigations of Momordica charantia Linn (Cucurbitaceae) in Senegal. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2019, 13, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, G.; Bag, M.; Sanodiya, B.S.; Bhadauriya, P.; Debnath, M.; Prasad, G.B.; Bisen, P.S. Momordica balsamina: A medicinal and neutraceutical plant for health care management. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2009, 10, 667–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omokhua-Uyi, A.G.; Staden, J.V. Phytomedicinal relevance of South African Cucurbitaceae species and their safety assessment: A review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 259, 112967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, H.S.; Tadmor, Y.; Schaffer, A.A. Cucurbitaceae, melons, squash, cucumber. In Encyclopedia of Applied Plant Sciences, 2nd ed.; Thomas, B., Murray, B.G., Murphy, D.J., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouquet, A. Plantes médicinales de la Côte d'Ivoire. Office de la Recherche Scientifique et Technique d'Outre-Mer (ORSTOM), Paris, 1974, 165, 38–39. 1974, 165, pp. 38–39. Available online: https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1571135650006923392.

- Ramalhete, C.; Mansoor, T.A.; Mulhovo, S.; Molnár, J.; Ferreira, M.J. Cucurbitane-type triterpenoids from the African plant Momordica balsamina. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72, 2009–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, H.; Renner, S.S. A three-genome phylogeny of Momordica (Cucurbitaceae) suggests seven returns from dioecy to monoecy and recent long-distance dispersal to Asia. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2010, 54, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flyman, M.V.; Afolayan, A.J. Proximate and mineral composition of the leaves of Momordica balsamina L.: An under-utilized wild vegetable in Botswana. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr 2007, 58, 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duenas-Lopez, M.A. Momordica balsamina (common balsam apple). Invasive Species Compendium (CABI Compendium) 2019, 34677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, I.; Yadav, S.K.; Hariprasad, G.; Gupta, R.C.; Srinivasan, A.; Batra, J.K.; Puri, M. Balsamin, a novel ribosome-inactivating protein from the seeds of Balsam apple Momordica balsamina. Amino acids. 2012, 43, 973–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, C.H. Momordica balsamina L (PROTA), Ressources végétales de l'Afrique tropicale. Available online: https://uses.plantnet-project.org/fr/Momordica_balsamina_(PROTA).

- Mamadou, A.O. Étude phytochimique et de l’activité antipaludique in vivo et in vitro de Momordica balsamina Linn. (Cucurbitaceae). Doctor of Pharmacy, FMPOS Bamako. 2005.

- Putri, H. Determination of total flavonoid content of ethanol extract of forest bitter melon (Momordica balsamina) leaves by uv-vis spectrophotometric method. Doctor of Pharmacy, Universitas_Muhammadiyah_Mataram. 2023.

- De Wet, H.; Ramulondi, M.; Ngcobo, Z.N. The use of indigenous medicine for the treatment of hypertension by a rural community in northern Maputaland, South Africa. South Afr. J. Bot. 2016, 103, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, N.; Gauttam, V.; Kalia, A.N. Evaluation of antidiabetic activity of Momordica balsamina Linn seeds in experimentally-induced diabetes. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 2010, 2, 701–707. [Google Scholar]

- Souda, S.; George, S.; Mannathoko, N.; Goercke, I.; Chabaesele, K. Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activity of Methanol Extract of Momordica balsamina. IRA- Int. J. Appl. Sci. 2018, 10, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit-Vical, F.; Grellier, P.; Abdoulaye, A.; Moussa, I.; Ousmane, A.; Berry, A.; Ikhiri, K.; Poupat, C. In vitro and in vivo Antiplasmodial Activity of Momordica balsamina Alone or in a Traditional Mixture. Chimiothérapie. 2006, 52, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jigam, A.A.; Akanya, H.O.; Adeyemi, D.J. Antimicrobial and antiplasmodial effects of Momordica balsamina. Nig. J. Nat. Prod. et Med. 2004, 8, 11–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otimenyin, S.O.; Uguru, M.O.; Ogbonna, A. Antimicrobial and hypoglycemic effects of Momordica balsamina. Linn. J. Nat. Prod. 2008, 1, 03–09. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/123456789/3130.

- Abdulhamid, A.; Jega, S.A.; Sani, I.; Bagudo, A.I.; Abubakar, R. Phytochemical and antibacterial activity of Mormodica balsamina leaves crude extract and fractions. Drug Discovery. 2023, 17, e11dd1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Diop, A.; Gbodossou, E.; Xiao, P.; Coleman, M.; De Barros, K.; Duong, H.; Bond, V.C.; Floyd, V.; Kondwani, K.; Rice, V.M. Anti-human immunodeficiency virus-1 activity of MoMo30 protein isolated from the traditional African medicinal plant Momordica balsamina. Journal de virologie. 2023, 20, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, M.I.; Khan, M.; Gbodossou, E.; Diop, A.; DeBarros, K.; Duong, H.; Bond, V.C.; Floyd, V.; Kondwani, K.; Montgomery, R.V.; Villinge, F.; Powell, M.D. Identification of a Novel Anti-HIV-1 Protein from Momordica balsamina Leaf Extract. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022, 19, 5227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khumalo, B.; Siboto, A.; Akinnuga, A.M.; Sibiya, N.; Khathi, A.; Ngubane, P.S. Effects of Momordica balsamina on markers associated with renal dysfunction in a diet-induced prediabetic rat model. Research Squar. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siboto, A.; Sibiya, N.; Khathi, A.; Ngubane, P. The effects of Momordica balsamina methanolic extract on kidney function in STZ-induced diabetic rats: Effects on selected metabolic markers. Journal of diabetes research. 2018, 2018, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kgopa, A.H.; Shai, L.J.; Mogale, M.A. Momordica balsamina fruit extracts enhance selected aspects of the insulin synthesis/secretion pathway. Am. J. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2020, 16, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampitan, T.; Garba, M.H.; Adekambi, D.I.; Ampitan, A.; Adelakun, K. Prophylactic potency of methanolic extract of Momordica balsamina l. Against avian paramyxovirus-1 infection in broiler chickens. Egyptian J. Anim. Prod. 2023, 60, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaila, A.T. Evaluation of Antifungal Efficacy of Lawsonia inermis, Momordica balsamina and Ziziphus mauritiana against Clinically Isolated Candida Species (Candida albicans, C. krusei, C. tropicalis, and C. parapsilosis). In Proceedings of the BOUESTI International Conference on Education, Science and Technology (ICEST), Bamidele Olumilua University of Education, Science and Technology, Ikere-Ekiti, Nigeria (21st -24th, November, 2022).

- Maibulangu, B.M.; Ibrahim, M.B.; Akinola, L.K. Inhibitory effect of African Pumpkin (Momordica balsamina Linn.) leaf extract on copper corrosion in acidic media. Journal of Applied Sciences and Environmental Management 2017, 21, 1067–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, L.G.; Umar, K.J. Nutritional value of Balsam Apple (Momordica balsamina L.) leaves. Pak. J. Nutr. 2006, 5, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehou, R.; Dougnon, V.; Atchade, p.; Attakpa, C.; Legba, B.; Baba-Moussa, L.; Gbaguidi, F. Etude phytochimique et toxicologique de cassia italica, Momordica balsamina et ocimum gratissimum, trois plantes utilisées contre la gale au sud-Bénin. Rev. Ivoir. Sci. Technol. 2018, 32, 286–297. [Google Scholar]

- Yolidjé, I.; Keita, D.A.; Moussa, I.; Toumane, A.; Maarouhi, I.M.; Saley, K.; Jean-Luc, P.; Much, O.J.T. Caractérisation Phytochimique et Activité Larvicide d’extraits Bruts de Plantes Issues de la Pharmacopée Traditionnelle du Niger sur les Larves d’. Anopheles gambiae. European Scientific Journal. 2019, 15, 30–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu’azu, A.; Bello, M. Reproductive Performance of Rabbit Feed With Graded of Balsam Apple (Momordica balsamina). J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2022, 9, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bot, Y.S.; Mgbojikwe, L.O.; Nwosu, C.; Abimiku, A.; Dadik, J.; Damshak, D. Screening of the fruit pulp extract of Momordica balsamina for anti-HIV property. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2007, 6, 047–052. [Google Scholar]

- Mabasa, X.E.; Mathomu, L.M.; Madala, N.E.; Musie, E.M.; Sigidi, M.T. Molecular spectroscopic (FTIR and UV-Vis) and hyphenated chromatographic (UHPLC-qTOF-MS) analysis and in vitro bioactivities of the Momordica balsamina leaf extract. Biochem. Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashiane, P.; Shoko, T.; Manhivi, V.; Slabbert, R.; Sultanbawa, Y.; Sivakumar, D. A Comparison of Bioactive Metabolites, Antinutrients, and Bioactivities of African Pumpkin Leaves (Momordica balsamina L.) Cooked by Different Culinary Techniques. Molecules. 2022, 27, 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalhete, C.; Gonçalves, B.M.; Barbosa, F.; Duarte, N.; Ferreira, M.J. Momordica balsamina: Phytochemistry and pharmacological potential of a gifted species. Phytochem. Rev. 2022, 21, 617–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajji, P.K.; Sonkar, S.P.; Walder, K.; Puri, M. Purification, and functional characterization of recombinant balsamin, a ribosome-inactivating protein from Momordica balsamina. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 114, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avato, P.; Argentieri, M.P. Editorial to the special issue: “Phytochemicals in nutrition and health: Advances and challenges. ” Phytochem. Rev. 2022, 21, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinthan, K.N.; Manjunathagowda, D.C.; Rathod, V.; Devan, S.R.; Anjanappa, M. Southern balsam pear (Momordica balsamina L.): Characterization of underutilized cucurbitaceous vegetable. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 145, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine. Les apports nutritionnels de référence : Le guide essential de besoins en nutriments; Meyers, L.D., Hellwig, J.P., Otten, J.J., Eds.; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO-World Health Organization. Energy and protein requirements: Report of a Joint FAO/WHO/UNU Expert Consultation [held in Rome from 5 to 17 October 1981]. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/62734. (accessed on 10 August 2023).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).