1. Introduction

Museum stores offer an avenue for discerning and delineating a marketing strategy exclusively linked to the fiscal objectives of the museum [

1]. In China, the total income of museum stores exceeded

$106 million in 2019, which accounted for a 33% increase compared with the previous year [

2]. Many Chinese museums operate online stores in the domestic market and include some other overseas museums like the British Museum. This presents a growing trend in the development of museum stores. Nevertheless, numerous museums continue to grapple with the daunting challenge of sustaining themselves due to the escalation of fixed expenses, such as rent, and intense competition from other museums and tourist destinations [

3]. Meanwhile, the revenue from museum gift shops represents only about 2% of the museum's total income in mainland Chinese [

2]. Therefore, the museum stores still have substantial potential for further growth and expansion. The Sanxingdui Museum in China released a collection of model toys known as the archaeological box, meticulously designed to incorporate elements from its bronze relics. In particular, these toys are intentionally coated with mud, providing customers with an immersive "archaeological experience" that simulates the discovery of cultural relics buried within the mud (see Appendix A). Moreover, customers do not know what the toy is inside the box until they remove the mud. This toy format has garnered significant market attention, prompting other museums to subsequently introduce similar products [

4].

Currently, customers' decision-making criteria not only focus on product pricing but also on product design [

5]. Designing products with a unique value for customers and users sets successful new products apart from those that fail [

6]. On the other hand, such museums that launched the archaeological box are famous and popular in China. Brand image is crucial for market success since it significantly affects customer loyalty [

7,

8,

9]. Moreover, scholars have also paid attention to the museum stores, specifically emphasizing the important role of the perceived value of the museum products [

10]. However, there are still some gaps in the literature. Specifically, in the context of the museum archaeological box, first, no studies have measured the multi-dimensions of product design (aesthetics and symbolism) and affective museum image in influencing behavioral intention. Second, none of the research has linked museum toy design with perceived value and consequently elicited behavioral intention, although the perceived value has been broadly investigated in predicting customers’ behavioral outcomes [

11,

12,

13]. Third, Li, Shu, Shao, Booth and Morrison [

10] have emphasized the importance of perceived value in museum products. However, no research examined if affective museum image triggers the perceived value of its product, and subsequently affects behavioral intention.

Attempting to fill these gaps, this study constructs an integrated model and aims to (1) account for the influence of multi-dimensions (aesthetics and symbolism) of museum archaeological box design on behavioral intention, (2) explore the role of affective museum image as a determinant of behavioral intention, (3) examine the effect of perceived value on behavioral intention, (4) identify the effect of the two design features on behavioral intention through perceived value, and (5) test the mediated role of perceived value in impacting the relationship between affective museum image and behavioral intention.

2. Literature review

2.1. Components of product design

Homburg, et al. [

14] found that product design comprises three crucial components: aesthetics, symbolism, and functionality. In this study, aesthetics pertains to the assessments and notions that arise when individuals appreciate an attractive and visually appealing object [

15,

16]. Allen [

17] defined symbolism as encompassing intangible concepts, associations tied to the product, and perceptions concerning the categories of individuals (e.g., interests) who engage with the product. As mentioned earlier, customers do not know what toy is inside the museum archaeological box when they purchase it. Hence, once customers gain a special toy, it may represent their achievement. Accordingly, it has symbolic features. Researchers have long recognized these three features in various research settings. For instance, enhancing the aesthetic appeal of a facility can assist an upscale restaurant in achieving effective competitiveness in the marketplace [

18]. In a study of beverage packaging, Machiels, et al. [

19] found that the symbolic elements of packaging contribute to improving consumers' perceptions of the product, achieving effective competitiveness in the marketplace. Morris [

20] proposed that strong product abilities enable the product to set itself apart from rivals. From a theoretical perspective, there is no doubt that product design significantly influences market behavior. However, considering the archaeological box without the functional property, the current study excludes functionality and hence adopts other two dimensions, aesthetics and symbolism, to examine the toy.

2.2. Impact of product design on behavioral intention

Prior research has identified the relationship between aesthetics and behavioral intention. By analyzing data collected from 223 customers, Xue [

21] found that purchase intention is an outcome of aesthetics. In a study of beauty category products, Sundar, et al. [

22] proposed that aesthetic packaging elicits customers’ purchase intention. Wang and Hsu [

23] hypothesized that interface aesthetics is an antecedent of purchase intention in a study context of smartwatches.

Scholars also found evidence of the effect of symbolism on behavioral intention. In an investigation of life fashion retailing, Chi and Chen [

24] demonstrated that if the products can provide social value, in other words, make the clients a good impression on other people, the clients will have a higher possibility to repurchase the products. Tsuchiya, et al. [

25] found that products with higher symbolic value will increase customers’ intention to shop. Self-expression can be described as the act of outwardly conveying or displaying one's self-identity [

26]. Aljukhadar, et al. [

27] mentioned that self-expression is a determinant of customer loyalty. Given the literature review, this study posits that:

H1a: Aesthetics positively impacts behavioral intention.

H1b: Symbolism positively impacts behavioral intention.

2.3. Impact of affective museum image on behavioral intention

In this study, affective museum image referred to feelings about a destination [

9]. Previous studies have researched the linkage between brand image and behavioral intention. Liang and Lai [

8] examined data gathered from 311 tourists, and they found that destination image predicts visit intention. In online shopping, store image is related to customers’ likelihood to purchase the products [

28]. Similarly, Febriyantoro [

29] stated that brand image directly influences purchase intention in an investigation of website marketing. Based on the findings, we hypothesize the following:

H2: Affective museum image positively impacts behavioral intention.

2.4. Impact of product design on perceived value

In this study, "perceived value" is defined as consumers' comprehensive evaluation of the product's inherent worth, derived from their assessment of the benefits offered by the item compared to the cost incurred by the consumers when using it [

30,

31]. Researchers have identified the relationship between product design and perceived value. For instance, in a study on mobile banking, Chaouali, et al. [

32] suggested that aesthetic design serves as a predictor for epistemic value. Mumcu and Kimzan [

33] noted that visual aesthetics have the potential to create value for a product and set it apart in the market. Packaging characteristics (e.g., packaging color) can evoke a sense of perceived value [

34].

Past research has highlighted the impact of symbolic characteristics on perceived value. For instance, the image of a restaurant encompasses symbolic elements that have a positive impact on customers' perceived value [

7]. Packaging designs for products can convey symbolic advantages [

34,

35], and Crilly, et al. [

36] argued that the symbolism associated with products allows individuals to express distinct facets of their personalities, including their values. Product characteristics involving self-expression and uniqueness have a positive effect on the perceived economic value [

37]. Given these, this study proposes the additional two hypotheses:

H3a: Aesthetics positively impacts perceived value.

H3b: Symbolism positively impacts perceived value.

2.5. Impact of affective museum image on perceived value

A limited number of previous studies found a connection between brand image and perceived value. In a study context of retail stores, Graciola, et al. [

38] noted that store image is a determinant of perceived value by analyzing data gathered from 298 retail consumers. A study of the bank sector by Zameer, et al. [

39] suggested that corporate image can predict customers’ perceived value. Similarly, another research in the service industry also identified that perceived value is an outcome of the restaurant image [

7]. The following hypothesis that therefore posited:

H4: Affective museum image positively impacts perceived value.

2.6. Impact of perceived value on behavioral intention

Scholars have broadly researched the effect of perceived value on behavioral intention in diverse fields.

Empirical findings within the restaurant industry have shown that perceived value precedes behavioral intention [

31]. Chen and Chen [

40] proposed that perceived value can enhance customers’ behavioral intentions. Perceived value, for instance, whether customers consider prices reasonable at a water park, positively affects behavioral intention (e.g., word-of-mouth intention) [

41]. In accordance with the existing literature, this study anticipates that participants who view Starbucks portable cups as offering a good value will exhibit a heightened level of behavioral intention. Therefore, the present study posits the following hypothesis:

H5: Perceived value positively impacts behavioral intention.

2.7. Mediating impact of perceived value

Marketing researchers have confirmed the important role of perceived value in consumer decision-making. For instance, in a study of mobile banking, Chaouali, Lunardo, Ben Yahia, Cyr and Triki [

32] suggested that the relationship between aesthetic design and intention to adopt can be mediated by perceived value. The perceived value of limited-edition shoes can increase customers’ likelihood of purchasing [

37]. Besides, these scholars also established that perceived value mediates the effect of uniqueness and self-expression on purchase intention. Moreover, perceived value plays a mediating role in the link between restaurant image and customers’ behavioral intention [

7]. Accordingly, this study proposed the following:

H6a: Perceived value mediates the effect of aesthetics and behavioral intention.

H6b: Perceived value mediates the effect of symbolism and behavioral intention.

H6c: Perceived value mediates the effect of affective museum image and behavioral intention.

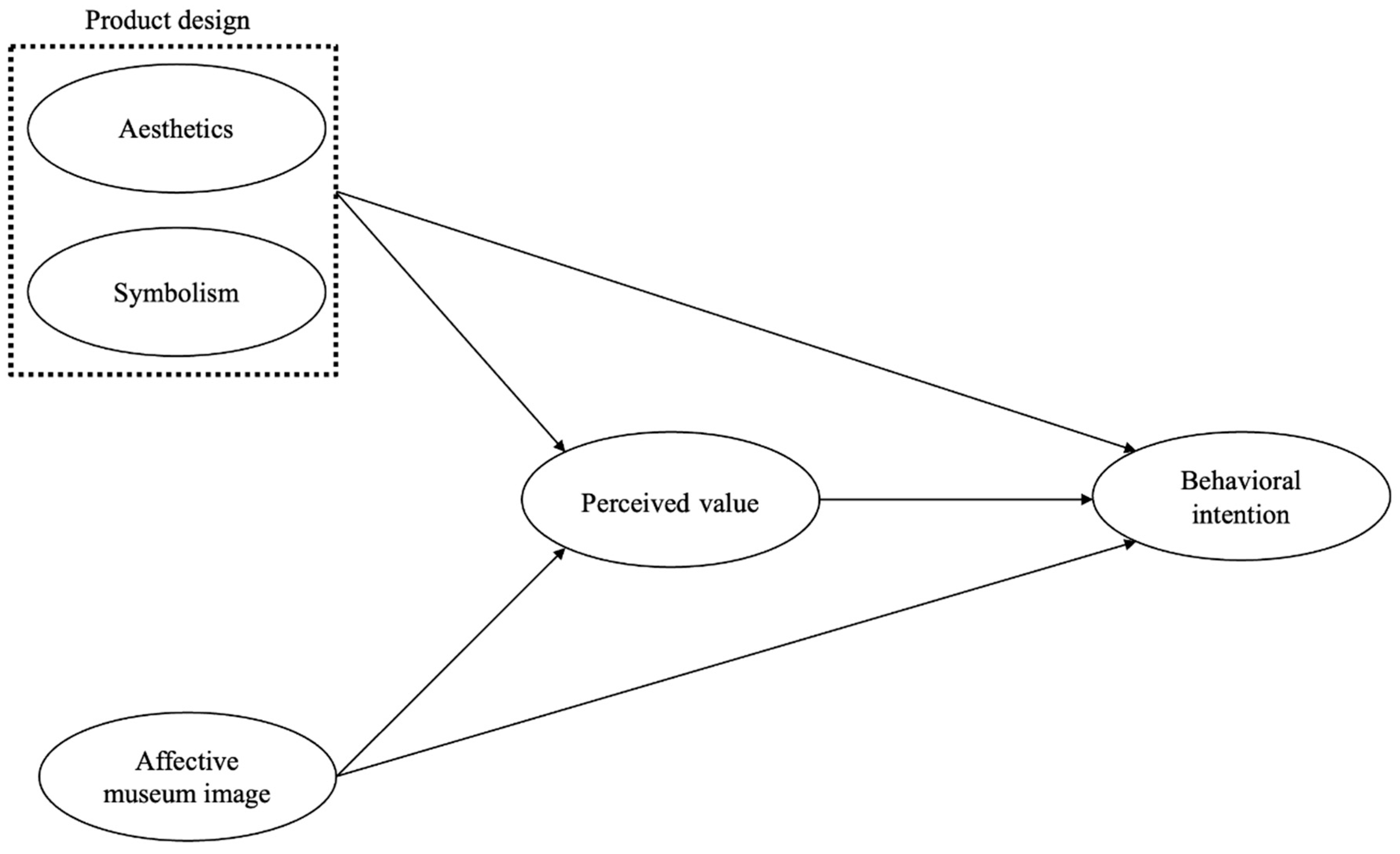

Based on the literature review and proposed relationships, the current study introduces a conceptual model, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data collection and participants

According to the National Bureau of Statistics (2019), revenue generated by museum stores in the Chinese mainland has exhibited an upward trend. This study's intended participants are individuals who have acquired a museum archaeological box from museum stores. The survey data were collected across mainland China's five most popular digital platforms, including one second-hand shopping application, one short-form video platform, and three online social communities. One of the authors, a native Chinese speaker, translated the measurement items into Chinese. Both an English language lecturer who teaches College English courses at Shantou University in China and a Chinese language lecturer who specializes in Chinese literature reviewed and proofread the translation. Afterward, another bilingual scholar translated the measurement items back into English to ensure translation accuracy. Then the authors began inquiring about individuals' willingness to participate in the questionnaire through personal messages and comments on the five social media platforms in late May 2022. From early July to the end of July 2022, a total of 633 web-based questionnaires were distributed to individuals willing to respond to the survey.

Consequently, 375 completed questionnaires were received, resulting in a response rate of 59.24%. However, 59 questionnaires were excluded including questionnaires submitted with missing data and those completed at an implausibly fast pace, resulting in 316 valid questionnaires remaining. As shown in

Table 1, among the respondents, 239 are female (75.6%), and 77 are male, making up 24.4% of the sample. There are 163 repeat purchasers, accounting for 51.6% of the sample. The majority of participants (65.8%) are aged between 20 and 29 years old (n = 208). Furthermore, a significant portion of the participants (69.9%) hold a bachelor's degree.

3.2. Measurement development

The current study encompassed a total of 5 latent variables: (a) aesthetics, (b) symbolism, (c) affective museum image, (d) perceived value, and (e) behavioral intention. All 15 measurement items were taken from existing literature related to product design (aesthetics and symbolism) [

15], affective image [

16], perceived value [

7], and behavioral intention [

7,

17]. These items were adapted to match the context of the museum archaeological box. Multi-items and a 7-point agree-disagree Likert scale from “Entirely disagree” (1) to “Entirely agree” (7) were used to measure all study constructs. A full list of all the items for each construct is provided in

Table 2.

3.3. Experiment procedure

Customers purchased the archaeological box from the museum stores but did not open it at once due to the “archaeological experience” mentioned previously. Therefore, the authors were not available to collect the questionnaires immediately after the museum archaeological box purchase behavior occurred, a series of toy photos are presented in the questionnaire. Typically, individuals can directly and immediately assess the aesthetic attributes of a product by examining its photograph. Additionally, Baek and Ok [

18] suggested that individuals can recognize the symbolic features of an object on a webpage. Accordingly, the authors selected six photos of museum archaeological toys from social media, which were asked for the agreements to use from the people who posted them on social media (see Appendix). Participants were required to view these photos before answering the questionnaires.

3.4. Data analysis

PLS-SEM is a well-established approach used to evaluate intricate cause-and-effect relationship models within the field of management studies [

19,

20]. Furthermore, research studies have confirmed the effectiveness of PLS-SEM in conducting research across various contexts within the hospitality and tourism industry field [

21,

22,

23]. In an effort to assess scale accuracy and the structural model, this study utilizes the partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) technique, employing Smart-PLS software version 4. PLS is particularly appropriate within the context of variance-based structural equation modeling (SEM) [

19,

24,

25].

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and validity

Statistical reliability of the measurements is assessed through Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability. Sarstedt, et al. [

26] suggested that to establish indicator reliability, factor loadings should exceed the threshold of 0.7. As shown in

Table 3, with factor loadings ranging from 0.838 to 0.945, the model's indicator reliability is thereby validated. Scholars proposed that internal consistency is considered evident when all Cronbach's alpha values and composite reliability scores exceed the recommended benchmark of 0.7 [

21]. As presented in

Table 3, all Cronbach's alpha values fell within the range of 0.822 to 0.909, and composite reliability ranged from 0.893 to 0.904, indicating strong evidence of internal consistency. Given these, internal consistency is established. Moreover, To confirm convergent validity, the average variance extracted (AVE) of the latent variables should surpass 0.5 as a criterion [

27]. All the AVE in this study ranged from 0.738 to 0.837. Accordingly, the convergent validity in this study is also established.

4.2. Discriminant validity

Voorhees, et al. [

28] recommended the Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT) should be less than 0.85 to assess discriminant validity. As displayed in

Table 4, all HTMT values being lower than 0.85 indicate that discriminant validity has been confirmed for the variables in the study. Further, researchers proposed that a Fornell & Larcker test should also be conducted because the HTMT approach may not identify a lack of discriminant validity in diverse research situations [

29].

Table 5 displays the outcomes of the Fornell & Larcker test, indicating that all correlations between the constructs are lower than the square roots of their respective average variance extracted (AVE) values, which confirms the discriminant validity [

27] (see

Table 5). Hence, all variables in the model are distinct from each other, confirming their uniqueness.

4.3. Common method bias

Kock, et al. [

30] indicated that when variables, both independent and dependent, are measured within a single questionnaire utilizing the same response method, there is a potential risk for common method bias. The variance inflation factor (VIF) was employed to assess multicollinearity and investigate whether there was any influence from common method bias. According to Kock and Lynn [

31], the inner VIFs should not exceed the threshold of 3.3. The findings indicate that all VIFs in the inner model fell within the range of 1.183 to 1.519, which is below the threshold, suggesting no significant issues with multi-collinearity.

4.4. Direct effect in the structural model

PLS-SEM was employed to assess the hypothesized direct relationships among the constructs. Through SmartPLS4, the analysis involved employing the bootstrapping technique with 5,000 subsamples and a path weighting scheme to test the hypotheses at a significant level of 0.05 [

32]. As shown in

Table 6, the results revealed that Hypothesis 1b, which proposed the positive effect of symbolism on behavioral intention (β = 0.058,

p < 0.001), was significant. Hypothesis 3a, which posited positive relationships between aesthetics and perceived value (β = 0.214,

p < 0.01) was significant. H3b, which hypothesized symbolism positively affects perceived value (β = 0.129, p < 0.05), was confirmed. Hypothesis 4 was statically established (β = 0.406, p < 0.001), indicating that affective museum image positively influences behavioral intention. Hypothesis 5 was supported (H5a: β = 0.416, p < 0.001), indicating that perceived value has significantly positive effects on behavioral intention. Nevertheless, H1a and H3, which propositioned the effects of aesthetics (t = 1.093, p = 0.275) and affective museum image (t = 1.938, p = 0.053) on behavioral intention, were rejected.

4.5. Indirect effect in the structural model

This paper also examined the mediated effect of perceived value in the relationship between design attributes (aesthetics and symbolism), affective museum image, and behavioral intention. Again, the bootstrapping technique with 95% confidence intervals, using 5,000 subsamples and a path weighting scheme, was employed to investigate the mediated effects within the model. As

Table 7 reveals, perceived value significantly mediated the linkage between aesthetics and behavioral intention (β = 0.089, p < 0.01). Accordingly, H6a was supported. H6b posited the mediating effect of perceived value in the path from symbolism and behavioral intention was significant (β = 0.053, p < 0.05). Given the finding, H6b was statically supported. H6c also established (β = 0.169, p < 0.001), indicating that perceived value was a mediator in the effect of affective museum image on behavioral intention.

5. Discussions and implications

This study incorporates two dimensions of product design (namely aesthetics and symbolism) as defined by Homburg et al. (2015). The consistent increase in attention to these two features of product design has resulted in marketing researchers’ investigations [

33,

34,

35]. Moreover, brand image is vital for market success as it profoundly influences customer loyalty [

7,

8]. However, these two attributes, along with brand image have not yet been extensively explored in tourism marketing research. This study addressed gaps in previous tourism marketing literature by developing a causal model and further gathering and analyzing data from consumers who had purchased archaeological museum boxes in the last three months. More specifically, first, this study empirically accounts for whether the design of museum archaeological boxes (encompassing aesthetics and symbolism) predicts customers’ behavioral intention. Second, this research seeks to determine how the affective museum image impacts behavioral intention. Third, this study analyzes how perceived value influences behavioral intention. Fourth, this paper examines the influence of the two design components on behavioral intention mediated by perceived value. Finally, this investigation tries to explain the mediating role of perceived value in affecting the path from affective museum image and behavioral intention.

5.1. Theoretical implications

This study makes a valuable contribution by uncovering associations that have not been previously investigated within the context of museum archaeological boxes. First, this study confirms that symbolism is a predictor of behavioral intention, consistent with prior research findings [

36,

37,

38]. Second, the result of this study shows that aesthetics is a determinant of perceived value, which corroborates the findings of other scholars in other contexts, such as a study of mobile banking by Chaouali, et al. [

39] and a research setting of product packaging by Wang and Yu [

40]. Third, this study tested and confirmed the association between symbolism and perceived value, in accordance with previous research [

7,

41]. Fifth, the findings of this study also found a significant effect of affective museum image on perceived value, consistent with the literature in diverse contexts, for instance, Graciola, et al. [

42] and Zameer, et al. [

43]. Sixth, this paper investigated the impact of perceived value on behavioral intention. Consequently, the present study analyzed and found evidence of perceived value as a mediator influence in the effect of aesthetics, symbolism, and affective museum image on behavioral outcomes. These findings are in line with prior investigations’ statements (see Chaouali, Lunardo, Ben Yahia, Cyr and Triki [

39], Chae, Kim, Lee and Park [

41], and Ryu et al., 2012).

Studies have focused on museum product consumption [

10,

44,

45], but none of them researched the study context of museum archaeological boxes, which became popular shortly after their release. Therefore, by analyzing the relationships between aesthetics, symbolism, affective museum image, perceived value, and behavioral intention in the current study setting, this study has filled the gap and made a contribution to the literature on tourism marketing. Furthermore, studies have long and widely emphasized the importance of the mediating effect of perceived value in various fields [

39,

41]. However, no studies considered aesthetics, symbolism, and affective museum image as antecedents of behavioral intention, particularly mediated by perceived value. Given these, this study has extended the literature by providing new evidence.

In addition, this study did not find the direct effect of aesthetics and affective museum image on perceived value. This may be due to the photos of the museum toys that the authors selected to present to the participants, which might not fit the participants' aesthetic preferences.

5.2. Practical implications

The study's findings offer meaningful implications for museum store management practices. By analyzing data gathered from individuals who have purchased museum archaeological boxes, this paper offers a comprehensive understanding of the insights that museum marketers and product designers should consider during the design process. First, this study affirmed that aesthetics predicts perceived value and, in turn, triggers behavioral intention. In other words, if customers feel the museum archaeological box toy is good-looking, they will believe the museum archaeological box offers good value for the price. Further, customers have a higher likelihood to repurchase the toys and also recommend the museum toys to their friends or others. As mentioned previously, the toys inside the archaeological box are the models of the museum’s collections. As the authors observed, these models totally look the same as the original collections, which are cultural relics with hundreds or even thousands of years. As scholars found that individuals' aesthetic values can evolve over time [

46], their preferences for aesthetics in artifacts may differ when comparing ancient and contemporary eras. Given this, designers may consider adding modern features to the toys, such as designing a model of cultural relics in a cartoon-like form. Moreover, customer input plays a pivotal role in shaping the product's design, dictating its requisite specifications and requirements [

6]. Marketers can systematically analyze comments about museum toys on social media to identify which toy attributes, such as color and shape, are most appealing to customers.

Second, the findings reveal that symbolism is a determinant of behavioral intention. If a museum toy enables customers to create a unique image on social media, customers will intend to purchase it again and suggest others to buy the toys. Moreover, symbolism elicits perceived value and subsequently impacts behavioral intention. The symbolic aspect of the toy can lead customers to perceive that the overall value of the museum archaeological box is high. The ensuing consumer loyalty will also be higher. As customers are unaware of the specific toy enclosed within the museum archaeological box at the time of purchase, when customers acquire a unique toy from it, it can symbolize achievement. As such, it possesses symbolic attributes. Given the importance of symbolism, marketers may consider launching more unique versions of toys, for instance, a series of limited editions, without disclosing what these special toys are when promoting them to the market. Chae, Kim, Lee and Park [

41] revealed that limited editions of products with uniqueness are significantly related to customer behavior.

Third, the current study found behavioral intention is a consequence of affective museum image. An impressive museum experience correlates with a higher probability of customers repurchasing the museum archaeological box and endorsing it to others. Moreover, affective museum image can result in perceived value, and in turn, influence behavioral intention. In simpler terms, if customers perceive the museum as impressive, they will view the museum archaeological box as a worthwhile expenditure. Subsequently, these customers are more likely to exhibit higher levels of loyalty. Social media marketing has garnered growing interest among marketers and is considered one of the most crucial channels for building a brand image [

14]. While the primary purpose of the museum store was initially to offer financial support for the affiliated institution, it now also serves as an educational or mission-oriented opportunity [

1]. For instance, marketers may consider operating social media accounts on short video platforms, presenting educational videos of the museum’s collections to the public. This may be an effective way to reinforce the museums’ brand image.

6. Limitations and future research

This study is limited to the tourism industry and specifically in the museum archaeological box context in China. Jacobsen [

47] demonstrated that cultural differences are related to perceptions such as aesthetic appreciation, and therefore, the result of this study may not be applied to examine museum products in other countries. Future studies may utilize the conceptual model from this study to investigate museum products in different countries and ascertain any disparities compared to the case in the present study. According to the report of National Bureau of Statistics [

2], the museum industry in mainland China has been developing rapidly. However, the revenue from museum stores currently represents a relatively small proportion of the total museum income. Therefore, there is still significant room for further growth. This study serves as a reference point for future research endeavors in the realm of product design within the heritage tourism marketing domain.

Author Contributions

All the authors contributed to the conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing of the original draft, and editing of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ali, F.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Ryu, K. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in hospitality research. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 2018, 30, 514–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljukhadar, M.; Bériault Poirier, A.; Senecal, S. Imagery makes social media captivating! Aesthetic value in a consumer-as-value-maximizer framework. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing 2020, 14, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.W. Human values and product Symbolism: Do consumers form product preference by comparing the human values symbolized by a product to the human values that they endorse? Journal of Applied Social Psychology 2002, 32, 2475–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asti, W.P.; Handayani, P.W.; Azzahro, F. Influence of trust, perceived value, and attitude on customers’ repurchase intention for e-grocery. Journal of Food Products Marketing 2021, 27, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.; Ok, C.M. The power of design: How does design affect consumers’ online hotel booking? International Journal of Hospitality Management 2017, 65, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, S. The Oxford dictionary of philosophy; OUP Oxford, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Blijlevens, J.; Carbon, C.-C.; Mugge, R.; Schoormans, J.P.L. Aesthetic appraisal of product designs: Independent effects of typicality and arousal. British Journal of Psychology 2012, 103, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K.A. Structural equations with latent variables; John Wiley & Sons., 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, C.; Louviere, J.; Young, L. Retaining the visitor, enhancing the experience: Identifying attributes of choice in repeat museum visitation. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 2009, 14, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CGTN. Chinese museums replicate archaeological digs with blind boxes. CGTN. 2020. Available online: https://news.cgtn.com/news/2020-12-06/Chinese-museums-replicate-archaeological-digs-with-blind-boxes-W04vm0SNEY/index.html.

- Chae, H.; Kim, S.; Lee, J.; Park, K. Impact of product characteristics of limited edition shoes on perceived value, brand trust, and purchase intention; focused on the scarcity message frequency. Journal of Business Research 2020, 120, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaouali, W.; Lunardo, R.; Ben Yahia, I.; Cyr, D.; Triki, A. Design aesthetics as drivers of value in mobile banking: Does customer happiness matter? International Journal of Bank Marketing 2020, 38, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charters, S. Aesthetic products and aesthetic consumption: A review. Consumption Markets & Culture 2006, 9, 235–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F.; Chen, F.-S. Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tourism Management 2010, 31, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.C.C. The impact of nostalgic emotions on consumer satisfaction with packaging design. Journal of Business and Retail Management Research 2014, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.L.; Pires, G.D.; Rosenberger III, P.J. Developing a conceptual model for examining social media marketing effects on brand awareness and brand image. International Journal of Economics and Business Research 2019, 17, 243–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, T.; Chen, Y. A study of lifestyle fashion retailing in China. Marketing Intelligence & Planning 2020, 38, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.G. The drivers of success in new-product development. Industrial Marketing Management 2019, 76, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crilly, N.; Moultrie, J.; Clarkson, P.J. Seeing things: Consumer response to the visual domain in product design. Design Studies 2004, 25, 547–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Febriyantoro, M.T. Exploring YouTube marketing communication: Brand awareness, brand image and purchase intention in the millennial generation. Cogent Business & Management 2020, 7, 1787733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilal, N.G.; Zhang, J.; Gilal, F.G. Linking product design to consumer behavior: The moderating role of consumption experience. Psychology research and behavior management 2018, 11, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goujot, A.H.; Florence, P.V. “All you need is love” from product design value perception to luxury brand love: An integrated framework. Journal of Business Research 2022, 139, 1463–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graciola, A.P.; De Toni, D.; Milan, G.S.; Eberle, L. Mediated-moderated effects: High and low store image, brand awareness, perceived value from mini and supermarkets retail stores. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2020, 55, 102117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudergan, S.P.; Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Will, A. Confirmatory tetrad analysis in PLS path modeling. Journal of Business Research 2008, 61, 1238–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis 2017, 1, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellier, P.K.; Geursen, G.M.; Carr, R.A.; Rickard, J.A. Customer repurchase intention: A general structural equation model. European Journal of Marketing 2003, 37, 1762–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, C.; Schwemmle, M.; Kuehnl, C. New product design: Concept, measurement, and consequences. Journal of Marketing 2015, 79, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, T. Beauty and the brain: Culture, history and individual differences in aesthetic appreciation. Journal of Anatomy 2010, 216, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, N.; Lee, S.; Lee, H. The effect of experience quality on perceived value, satisfaction, image and behavioral intention of water park patrons: New versus repeat visitors. International Journal of Tourism Research 2015, 17, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, F.; Berbekova, A.; Assaf, A.G. Understanding and managing the threat of common method bias: Detection, prevention and control. Tourism Management 2021, 86, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G. Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. Journal of the Association for information Systems 2012, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, K.F.; Pérez, A.; Sahibzada, U.F. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) and customer loyalty in the hotel industry: A cross-country study. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2020, 89, 102565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, A.N.H.; Khoi, N.H.; Nguyen, D.P. Unraveling the dynamic and contingency mechanism between service experience and customer engagement with luxury hotel brands. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2021, 99, 103057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Shu, S.; Shao, J.; Booth, E.; Morrison, A.M. Innovative or not? The effects of consumer perceived value on purchase intentions for the Palace Museum’s cultural and creative products. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.-H.; Lai, I.K.W. Tea tourism: Designation of origin brand image, destination image, and visit intention. Journal of Vacation Marketing 2022, 29, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-H.; Morais, D.B.; Kerstetter, D.L.; Hou, J.-S. Examining the role of cognitive and affective image in predicting choice across natural, developed, and theme-park destinations. Journal of Travel Research 2007, 46, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machiels, C.J.A.; Yarar, N.; Orth, U.R. 4 - Symbolic meaning in beverage packaging and consumer response. In Trends in beverage packaging; Grumezescu, A.M., Holban, A.M., Eds.; Academic Press, 2019; pp. 73–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.; Park, J.; Kim, S. The importance of an innovative product design on customer behavior: Development and validation of a scale. Journal of Product Innovation Management 2015, 32, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, C.; Townsend, C. Why the drive: The utilitarian and hedonic benefits of self-expression through consumption. Current Opinion in Psychology 2022, 46, 101320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, R. The fundamentals of product design; Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mottner, S.; Ford, J.B. Measuring nonprofit marketing strategy performance: The case of museum stores. Journal of Business Research 2005, 58, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumcu, Y.; Kimzan, H.S. The effect of visual product aesthetics on consumers’ price sensitivity. Procedia Economics and Finance 2015, 26, 528–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics. Heritage stores income in China. 2019. Available online: https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=C01&zb=A0Q0703&sj=2022.

- Nisar, Q.A.; Haider, S.; Ali, F.; Naz, S.; Ryu, K. Depletion of psychological, financial, and social resources in the hospitality sector during the pandemic. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2021, 93, 102794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Lennon, S.J. Brand name and promotion in online shopping contexts. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal 2009, 13, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravenal, J.B. FORUM: Saving the museum through partnership. Curator: The Museum Journal 2021, 64, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A.; Dhir, A.; Bala, P.K.; Kaur, P. Why do people use food delivery apps (FDA)? A uses and gratification theory perspective. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2019, 51, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Han, H.; Jang, S. Relationships among hedonic and utilitarian values, satisfaction and behavioral intentions in the fast-casual restaurant industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 2010, 22, 416–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Han, H.; Kim, T.-H. The relationships among overall quick-casual restaurant image, perceived value, customer satisfaction, and behavioral intentions. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2008, 27, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Jang, S.S. The effect of environmental perceptions on behavioral intentions through emotions: The case of upscale restaurants. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 2007, 31, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Lee, H.R.; Gon Kim, W. The influence of the quality of the physical environment, food, and service on restaurant image, customer perceived value, customer satisfaction, and behavioral intentions. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 2012, 24, 200–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, E.M.; Pérez, J.M.P. Modeling the brand extensions' influence on brand image. Journal of Business Research 2009, 62, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial least squares structural equation modeling. Handbook of market research 2022, 587–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirpke, U.; Zoderer, B.M.; Tappeiner, U.; Tasser, E. Effects of past landscape changes on aesthetic landscape values in the European Alps. Landscape and Urban Planning 2021, 212, 104109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.K.; Verma, P. Impact of sales promotion's benefits on perceived value: Does product category moderate the results? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2020, 52, 101887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, A.; Cao, E.S.; Machleit, K.A. How product aesthetics cues efficacy beliefs of product performance. Psychology & Marketing 2020, 37, 1246–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touni, R.; Kim, W.G.; Haldorai, K.; Rady, A. Customer engagement and hotel booking intention: The mediating and moderating roles of customer-perceived value and brand reputation. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2022, 104, 103246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, N.K.F.; Zhu, M.; Au, W.C.W. Investigating the attributes of cultural creative product satisfaction - The case of the Palace Museum. Journal of China Tourism Research 2022, 18, 1239–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, H.; Fu, Y.-M.; Huang, S.C.-T. Customer value, purchase intentions and willingness to pay: The moderating effects of cultural/economic distance. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 2022, 34, 268–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorhees, C.M.; Brady, M.K.; Calantone, R.; Ramirez, E. Discriminant validity testing in marketing: An analysis, causes for concern, and proposed remedies. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 2016, 44, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.S.T.; Yu, J.-R. Effect of product attribute beliefs of ready-to-drink coffee beverages on consumer-perceived value and repurchase intention. British Food Journal 2016, 118, 2963–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hsu, Y. Does sustainable perceived value play a key role in the purchase intention driven by product aesthetics? Taking smartwatch as an example. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J. An investigation into the effects of product design on incremental and radical innovations from the perspective of consumer perceptions: Evidence from China. Creativity and Innovation Management 2019, 28, 501–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zameer, H.; Tara, A.; Kausar, U.; Mohsin, A. Impact of service quality, corporate image and customer satisfaction towards customers’ perceived value in the banking sector in Pakistan. International Journal of Bank Marketing 2015, 33, 442–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).