Submitted:

17 September 2023

Posted:

19 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

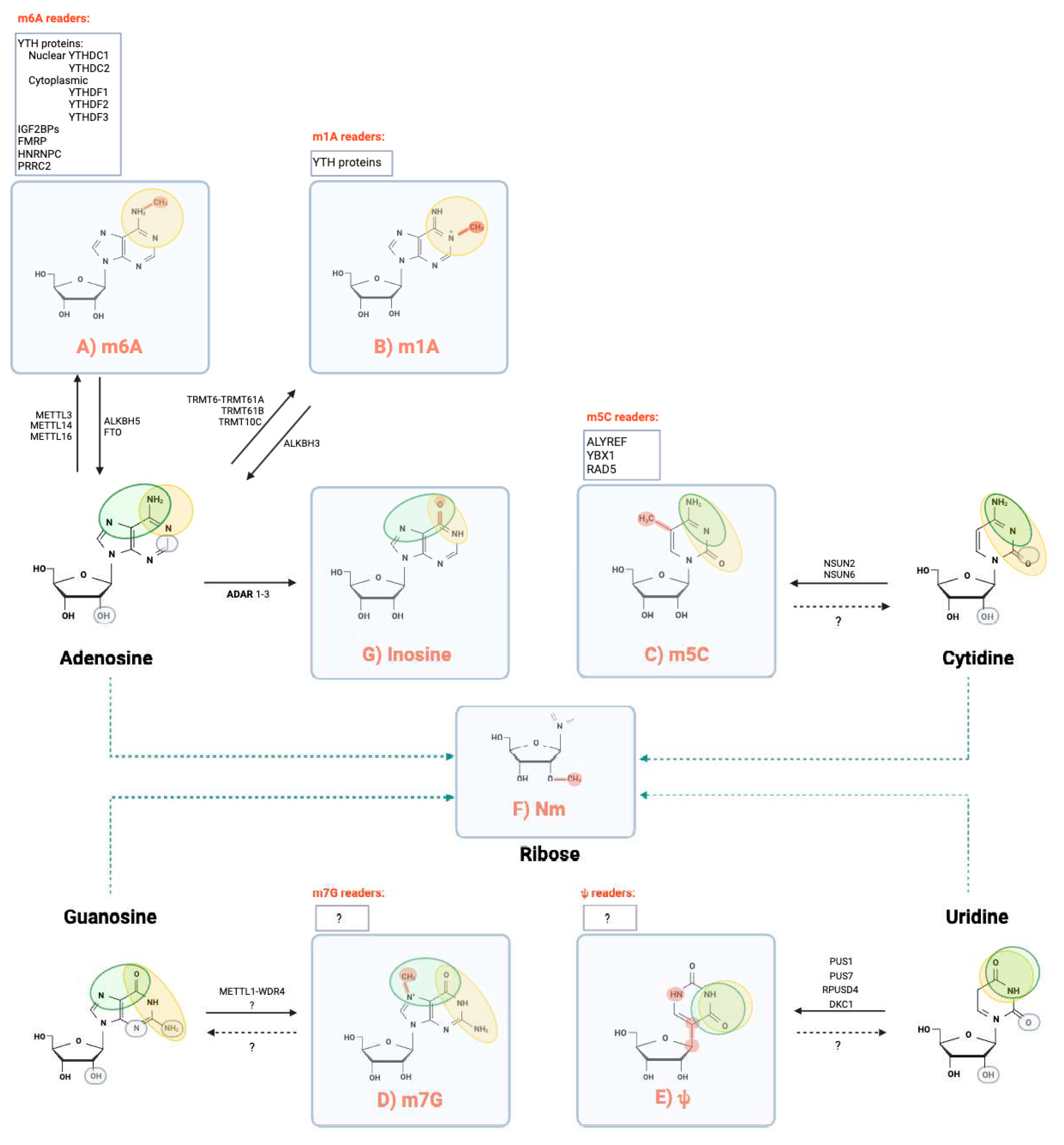

1. Epitranscriptomics at a glance

1.1. N⁶-Methyladenosine (m6A)

1.2. N1-methyladenosine (m1A)

1.3. 5-methylcytidine (m5C)

1.4. 7-methylguanosine (m7G)

1.5. Pseudouridine (Ψ)

1.6. 2’-O-methylation (Nm or 2’-O-Me)

1.7. Nucleoside editing

| Modified ribonucleoside | Stoichiometry | Target sequence | mRNA preferred regions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| m6A | 0.2-0.6% m6A/A | DRACH | 5’ UTR, near the stop codon, 3’ UTR | |

| m1A | 0,01-0,05% m1A/A | GC-rich and GA-rich sequence, GUUCNANNC | All segments of the transcripts, enriched in: first splice site, GC rich highly structured regions in the 5’ UTRs, translation start site | |

| m5C | 0,03-0,1% m5C/C | CTCCA | 5′/3′ UTRs, next to Argonaute-binding regions | |

| m7G | 0.002-0.05% m7G/G | GA- or GG-enriched sequence motifs | 5′UTR near the start codon and near the stop codon, | |

| Ψ | 0.2-0.6% Ψ/U | AU (PUS1-specific)GUUCNANYCY(PUS4)UGUAGPUS7) | Coding sequence and 3’UTR. | |

| Nm | 0,01% Nm/N | NmAGAUC followed by a 5-nt-long AG-rich stretch | CDS, near splice sites, 5’/3’ UTR, introns, alternatively spliced regions | |

| A to I | Not available | dsRNA, preference for U in the -1 position | Introns (Alu sequences) and UTRs; coding sequence | |

2. Epitranscriptomics in skeletal muscle

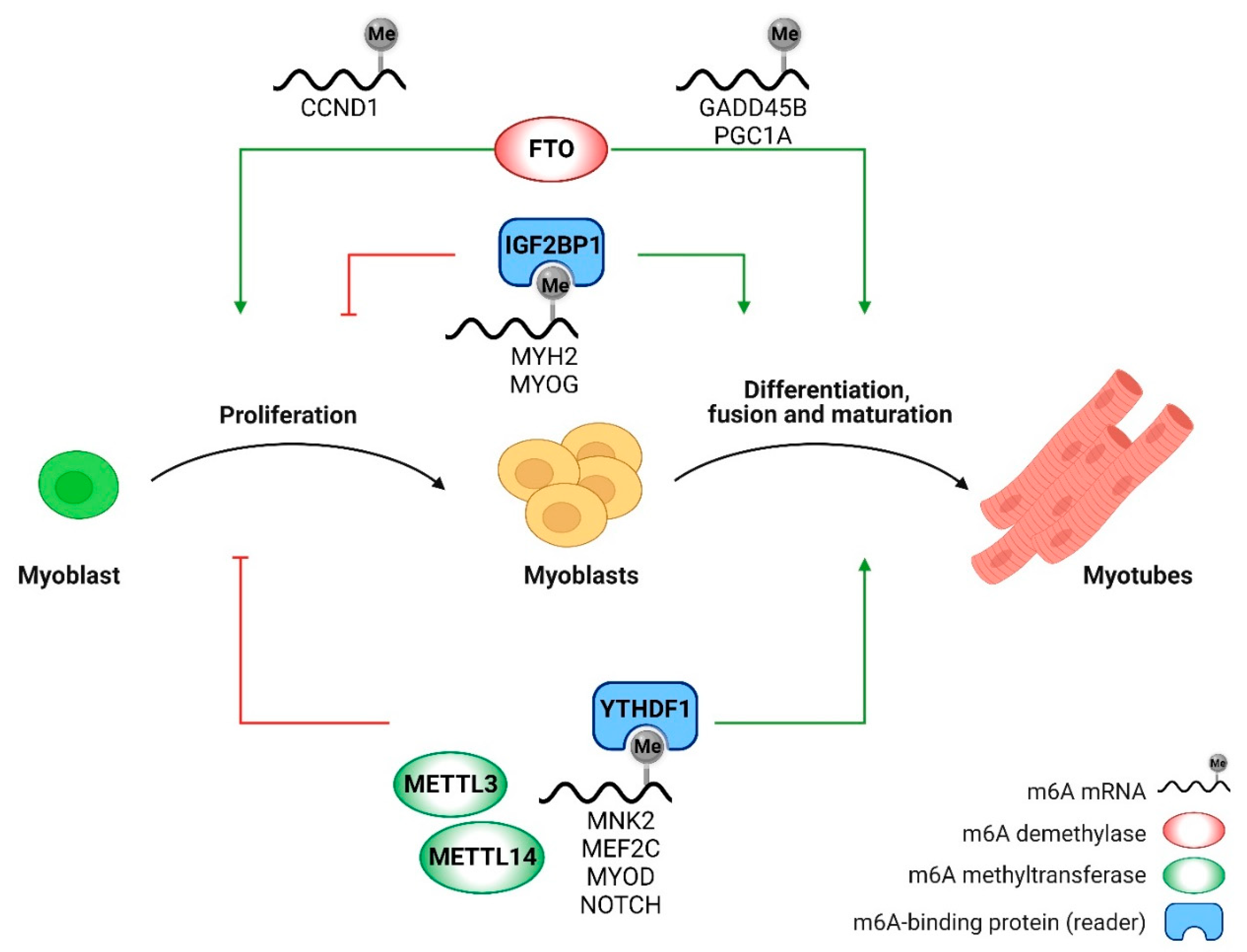

2.1. N⁶-Methyladenosine modification in embryonic myogenesis

2.2. N⁶-Methyladenosine modification in myoblast differentiation

2.3. N⁶-Methyladenosine modification in skeletal muscle homeostasis

3. Epitranscriptomics as novel pathogenetic mechanism and potential therapeutic approach for muscular disorders

| Gene | Gene ID | m6A | m1A | m5C | m7G | PseudoU | 2'-O-Me | RNA-editing, A-I sites | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACTA1 | ENSG00000143632.14 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| ANO5 | ENSG00000171714.11 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 26 |

| B3GALNT2 | ENSG00000162885.13 | 13 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 23 |

| B4GAT1 | ENSG00000174684.7 | 27 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 29 |

| BVES | ENSG00000112276.14 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 12 |

| CACNA1S | ENSG00000081248.11 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| CAPN3 | ENSG00000092529.24 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 19 |

| CAV3 | ENSG00000182533.6 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| CAVIN1 | ENSG00000177469.13 | 45 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 46 |

| CHKB | ENSG00000100288.19 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 26 |

| COL12A1 | ENSG00000111799.21 | 203 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 203 |

| COL6A1 | ENSG00000142156.14 | 93 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 93 |

| COL6A2 | ENSG00000142173.15 | 88 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 91 |

| COL6A3 | ENSG00000163359.15 | 144 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 150 |

| DAG1 | ENSG00000173402.11 | 138 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 147 |

| DES | ENSG00000175084.11 | 35 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 36 |

| DMD | ENSG00000198947.15 | 116 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 137 |

| DNAJB6 | ENSG00000105993.15 | 86 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 108 |

| DNM2 | ENSG00000079805.16 | 118 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 29 | 161 |

| DPM1 | ENSG00000000419.12 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 16 | 42 |

| DPM2 | ENSG00000136908.17 | 54 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 54 |

| DPM3 | ENSG00000179085.7 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| DYSF | ENSG00000135636.14 | 33 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 38 |

| EMD | ENSG00000102119.10 | 22 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 32 |

| FHL1 | ENSG00000022267.17 | 76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 82 |

| FKRP | ENSG00000181027.10 | 64 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 76 |

| FKTN | ENSG00000106692.14 | 49 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 54 |

| GAA | ENSG00000171298.13 | 69 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 77 |

| GGPS1 | ENSG00000152904.11 | 83 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 89 |

| GMPPB | ENSG00000173540.12 | 76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 77 |

| GOLGA2 | ENSG00000167110.17 | 81 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 94 |

| GOSR2 | ENSG00000108433.16 | 139 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 142 |

| HNRNPDL | ENSG00000152795.17 | 94 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 98 |

| INPP5K | ENSG00000132376.20 | 62 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 64 |

| ITGA7 | ENSG00000135424.16 | 39 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 39 |

| JAG2 | ENSG00000184916.9 | 48 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 53 |

| LAMA2 | ENSG00000196569.12 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 25 |

| LARGE1 | ENSG00000133424.20 | 62 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 63 | 126 |

| LIMS2 | ENSG00000072163.19 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 29 |

| LMNA | ENSG00000160789.20 | 72 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 22 | 100 |

| LRIF1 | ENSG00000121931.16 | 72 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 72 |

| MPDU1 | ENSG00000129255.16 | 36 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 38 |

| MSTO1 | ENSG00000125459.15 | 33 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 35 |

| MYOT | ENSG00000120729.9 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| PLEC | ENSG00000178209.15 | 167 | 0 | 26 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 21 | 217 |

| POGLUT1 | ENSG00000163389.12 | 37 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 40 |

| POMGNT1 | ENSG00000085998.14 | 59 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 60 |

| POMGNT2 | ENSG00000144647.6 | 49 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 51 |

| POMK | ENSG00000185900.9 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 24 |

| POMT1 | ENSG00000130714.16 | 53 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 73 |

| POMT2 | ENSG00000009830.11 | 66 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 73 |

| POPDC3 | ENSG00000132429.10 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 |

| PYROXD1 | ENSG00000121350.16 | 48 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 51 |

| RXYLT1 | ENSG00000118600.11 | 23 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 26 |

| RYR1 | ENSG00000196218.12 | 32 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 37 |

| SELENON | ENSG00000162430.17 | 59 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 78 |

| SGCA | ENSG00000108823.16 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| SGCB | ENSG00000163069.12 | 61 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 80 |

| SGCG | ENSG00000102683.7 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| SMCHD1 | ENSG00000101596.15 | 153 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 171 |

| SYNE1 | ENSG00000131018.23 | 339 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 50 | 399 |

| SYNE2 | ENSG00000054654.16 | 482 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 506 |

| TCAP | ENSG00000173991.5 | 11 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 |

| TMEM43 | ENSG00000170876.7 | 89 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 91 |

| TNPO3 | ENSG00000064419.13 | 94 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 103 |

| TOR1AIP1 | ENSG00000143337.18 | 90 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 98 |

| TRAPPC11 | ENSG00000168538.16 | 67 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 70 |

| TRIM32 | ENSG00000119401.10 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 39 |

| TRIP4 | ENSG00000103671.9 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 34 |

| TTN | ENSG00000155657.26 | 249 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 255 |

| VCP | ENSG00000165280.16 | 84 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 100 |

| Gene | Gene ID | m6A | m1A | m5C | m7G | PseudoU | 2'-O-Me | RNA-editing, A-I sites | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EZH2 | ENSG00000106462.10 | 52 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 57 |

| HDAC4 | ENSG00000068024.16 | 80 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 109 |

| MEF2A | ENSG00000068305.17 | 128 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 49 | 180 |

| MEF2C | ENSG00000081189.15 | 41 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 44 |

| MEF2D | ENSG00000116604.18 | 38 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 48 |

| MYF5 | ENSG00000111049.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MYH1 | ENSG00000109061.10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| MYH2 | ENSG00000125414.19 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| MYOD1 | ENSG00000129152.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NFYA | ENSG00000001167.14 | 79 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 87 |

| PAX3 | ENSG00000135903.19 | 59 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 59 |

| PAX7 | ENSG00000009709.12 | 37 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 37 |

| SIRT1 | ENSG00000096717.12 | 76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 103 |

| SMAD4 | ENSG00000141646.13 | 104 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 113 |

Author Contributions

Funding

References

- He, C. Grand Challenge Commentary: RNA epigenetics? Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010, 6, 863–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribonucleic Acids from Yeast Which Contain a Fifth Nucleotide - PubMed Available online:. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/13463012/ (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- Boccaletto, P.; Stefaniak, F.; Ray, A.; Cappannini, A.; Mukherjee, S.; Purta, E.; Kurkowska, M.; Shirvanizadeh, N.; Destefanis, E.; Groza, P.; et al. MODOMICS: a database of RNA modification pathways. 2021 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 50, D231–D235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halder, S.; Bhattacharyya, D. RNA structure and dynamics: A base pairing perspective. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2013, 113, 264–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G.; Fu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Dai, Q.; Zheng, G.; Yang, Y.; Yi, C.; Lindahl, T.; Pan, T.; Yang, Y.-G.; et al. N6-Methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 7, 885–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C. Grand Challenge Commentary: RNA epigenetics? Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010, 6, 863–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimeno, S.; Balestra, F.R.; Huertas, P. The Emerging Role of RNA Modifications in DNA Double-Strand Break Repair. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, F.; Tang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Qin, H.; Liu, S.; Wu, M.; Feng, P.; Chen, W. RNAME: A comprehensive database of RNA modification enzymes. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 6244–6249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonkhout, N.; Tran, J.; Smith, M.A.; Schonrock, N.; Mattick, J.S.; Novoa, E.M. The RNA modification landscape in human disease. RNA 2017, 23, 1754–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, L.; Li, X. Detection technologies for RNA modifications. Exp. Mol. Med. 2022, 54, 1601–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xiong, X.; Yi, C. Epitranscriptome sequencing technologies: Decoding RNA modifications. Nat. Methods 2016, 14, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, D.; Schwartz, S. The epitranscriptome beyond m6A. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2020, 22, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yankova, E.; Blackaby, W.; Albertella, M.; Rak, J.; De Braekeleer, E.; Tsagkogeorga, G.; Pilka, E.S.; Aspris, D.; Leggate, D.; Hendrick, A.G.; et al. Small-molecule inhibition of METTL3 as a strategy against myeloid leukaemia. Nature 2021, 593, 597–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xuan, J.-J.; Sun, W.-J.; Lin, P.-H.; Zhou, K.-R.; Liu, S.; Zheng, L.-L.; Qu, L.-H.; Yang, J.-H. RMBase v2.0: deciphering the map of RNA modifications from epitranscriptome sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 46, D327–D334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbriano, C.; Molinari, S. Alternative Splicing of Transcription Factors Genes in Muscle Physiology and Pathology. Genes 2018, 9, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benarroch, L.; Bonne, G.; Rivier, F.; Hamroun, D. The 2023 version of the gene table of neuromuscular disorders (nuclear genome). Neuromuscul. Disord. 2022, 33, 76–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauer, J.; Luo, X.; Blanjoie, A.; Jiao, X.; Grozhik, A.V.; Patil, D.P.; Linder, B.; Pickering, B.F.; Vasseur, J.-J.; Chen, Q.; et al. Reversible methylation of m6Am in the 5′ cap controls mRNA stability. Nature 2017, 541, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akichika, S.; Hirano, S.; Shichino, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Nishimasu, H.; Ishitani, R.; Sugita, A.; Hirose, Y.; Iwasaki, S.; Nureki, O.; et al. Cap-specific terminal N 6 -methylation of RNA by an RNA polymerase II–associated methyltransferase. Science 2019, 363, 141–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.-M.; Gershowitz, A.; Moss, B. Methylated nucleotides block 5′ terminus of HeLa cell messenger RNA. Cell 1975, 4, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, S.; Lavi, U.; Darnell, J.E. The absolute frequency of labeled N-6-methyladenosine in HeLa cell messenger RNA decreases with label time. J. Mol. Biol. 1978, 124, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Dominissini, D.; Rechavi, G.; He, C. Gene expression regulation mediated through reversible m6A RNA methylation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014, 15, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, S.; Huang, L.; Lilley, D.M.J. Effect of methylation of adenine N6 on kink turn structure depends on location. RNA Biol. 2019, 16, 1377–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulias, K.; Greer, E.L. Biological roles of adenine methylation in RNA. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 24, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, C.-M.; Moss, B. Nucleotide sequences at the N6-methyladenosine sites of HeLa cell messenger ribonucleic acid. Biochemistry 1977, 16, 1672–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schibler, U.; Kelley, D.E.; Perry, R.P. Comparison of methylated sequences in messenger RNA and heterogeneous nuclear RNA from mouse L cells. J. Mol. Biol. 1977, 115, 695–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K.D.; Saletore, Y.; Zumbo, P.; Elemento, O.; Mason, C.E.; Jaffrey, S.R. Comprehensive Analysis of mRNA Methylation Reveals Enrichment in 3′ UTRs and near Stop Codons. Cell 2012, 149, 1635–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.; Bernstein, D.A.; Mumbach, M.R.; Jovanovic, M.; Herbst, R.H.; León-Ricardo, B.X.; Engreitz, J.M.; Guttman, M.; Satija, R.; Lander, E.S.; et al. Transcriptome-wide Mapping Reveals Widespread Dynamic-Regulated Pseudouridylation of ncRNA and mRNA. Cell 2014, 159, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K.D.; Patil, D.P.; Zhou, J.; Zinoviev, A.; Skabkin, M.A.; Elemento, O.; Pestova, T.V.; Qian, S.-B.; Jaffrey, S.R. 5′ UTR m6A Promotes Cap-Independent Translation. Cell 2015, 163, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slobodin, B.; Han, R.; Calderone, V.; Vrielink, J.A.O.; Loayza-Puch, F.; Elkon, R.; Agami, R. Transcription Impacts the Efficiency of mRNA Translation via Co-transcriptional N6-adenosine Methylation. Cell 2017, 169, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokar, J.A.; Shambaugh, M.E.; Polayes, D.; Matera, A.G.; Rottman, F.M. Human MRNA (N6-Adenosine)-Methyltransferase Purification and CDNA Cloning of the AdoMet-Binding Subunit of The. 1997, 3, 1233–1247.

- Pendleton, K.E.; Chen, B.; Liu, K.; Hunter, O.V.; Xie, Y.; Tu, B.P.; Conrad, N.K. The U6 snRNA m 6 A Methyltransferase METTL16 Regulates SAM Synthetase Intron Retention. Cell 2017, 169, 824–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G.; Fu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Dai, Q.; Zheng, G.; Yang, Y.; Yi, C.; Lindahl, T.; Pan, T.; Yang, Y.-G.; et al. N6-Methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 7, 885–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, G.; Dahl, J.A.; Niu, Y.; Fedorcsak, P.; Huang, C.-M.; Li, C.J.; Vågbø, C.B.; Shi, Y.; Wang, W.-L.; Song, S.-H.; et al. ALKBH5 Is a Mammalian RNA Demethylase that Impacts RNA Metabolism and Mouse Fertility. Mol. Cell 2013, 49, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.; Li, A.; Sun, B.; Sun, J.-G.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, T.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; et al. A novel m6A reader Prrc2a controls oligodendroglial specification and myelination. Cell Res. 2018, 29, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Weng, H.; Sun, W.; Qin, X.; Shi, H.; Wu, H.; Zhao, B.S.; Mesquita, A.; Liu, C.; Yuan, C.L.; et al. Recognition of RNA N6-methyladenosine by IGF2BP proteins enhances mRNA stability and translation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edupuganti, R.R.; Geiger, S.; Lu, Z.; Wang, S.-Y.; Baltissen, M.P.A.; Jansen, P.W.T.C.; Rossa, M.; Müller, M.; Stunnenberg, H.G.; He, C.; et al. N6-methyladenosine (m6A) recruits and repels proteins to regulate mRNA homeostasis. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017, 24, 870–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, P.J.; Shi, H.; Zhu, A.C.; Lu, Z.; Miller, N.; Edens, B.M.; Ma, Y.C.; He, C. The RNA-binding protein FMRP facilitates the nuclear export of N6-methyladenosine–containing mRNAs. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 19889–19895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Dai, Q.; Zheng, G.; He, C.; Parisien, M.; Pan, T. N6-methyladenosine-dependent RNA structural switches regulate RNA–protein interactions. Nature 2015, 518, 560–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón, C.R.; Goodarzi, H.; Lee, H.; Liu, X.; Tavazoie, S.; Tavazoie, S.F. HNRNPA2B1 Is a Mediator of m6A-Dependent Nuclear RNA Processing Events. Cell 2015, 162, 1299–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haussmann, I.U.; Bodi, Z.; Sanchez-Moran, E.; Mongan, N.P.; Archer, N.; Fray, R.G.; Soller, M. m6A potentiates Sxl alternative pre-mRNA splicing for robust Drosophila sex determination. Nature 2016, 540, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roundtree, I.A.; Luo, G.-Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhou, T.; Cui, Y.; Sha, J.; Huang, X.; Guerrero, L.; Xie, P.; et al. YTHDC1 mediates nuclear export of N6-methyladenosine methylated mRNAs. eLife 2017, 6, e31311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edens, B.M.; Vissers, C.; Su, J.; Arumugam, S.; Xu, Z.; Shi, H.; Miller, N.; Ringeling, F.R.; Ming, G.-L.; He, C.; et al. FMRP Modulates Neural Differentiation through m6A-Dependent mRNA Nuclear Export. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominissini, D.; Moshitch-Moshkovitz, S.; Schwartz, S.; Salmon-Divon, M.; Ungar, L.; Osenberg, S.; Cesarkas, K.; Jacob-Hirsch, J.; Amariglio, N.; Kupiec, M.; et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature 2012, 485, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garbo, S.; Zwergel, C.; Battistelli, C. m6A RNA methylation and beyond – The epigenetic machinery and potential treatment options. Drug Discov. Today 2021, 26, 2559–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonkhout, N.; Tran, J.; Smith, M.A.; Schonrock, N.; Mattick, J.S.; Novoa, E.M. The RNA modification landscape in human disease. RNA 2017, 23, 1754–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T. The expanding world of tRNA modifications and their disease relevance. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leptidis, S.; Papakonstantinou, E.; Diakou, K.I.; Pierouli, K.; Mitsis, T.; Dragoumani, K.; Bacopoulou, F.; Sanoudou, D.; Chrousos, G.P.; Vlachakis, D. Epitranscriptomics of cardiovascular diseases (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2021, 49, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, I.; Kouzarides, T. Role of RNA modifications in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Zhu, X.; Novák, P.; Zhou, L.; Gao, L.; Yang, M.; Zhao, G.; Yin, K. The epitranscriptome of long noncoding RNAs in metabolic diseases. Clin. Chim. Acta 2021, 515, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominissini, D.; Nachtergaele, S.; Moshitch-Moshkovitz, S.; Peer, E.; Kol, N.; Ben-Haim, M.S.; Dai, Q.; Di Segni, A.; Salmon-Divon, M.; Clark, W.C.; et al. The dynamic N1-methyladenosine methylome in eukaryotic messenger RNA. Nature 2016, 530, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xiong, X.; Wang, K.; Wang, L.; Shu, X.; Ma, S.; Yi, C. Transcriptome-wide mapping reveals reversible and dynamic N1-methyladenosine methylome. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2016, 12, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Li, K.; Liu, C.; Yi, C. Regulation and functions of non-m6A mRNA modifications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saikia, M.; Fu, Y.; Pavon-Eternod, M.; He, C.; Pan, T. Genome-wide analysis of N1-methyl-adenosine modification in human tRNAs. RNA 2010, 16, 1317–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sloan, K.E.; Warda, A.S.; Sharma, S.; Entian, K.-D.; Lafontaine, D.L.J.; Bohnsack, M.T. Tuning the ribosome: The influence of rRNA modification on eukaryotic ribosome biogenesis and function. RNA Biol. 2016, 14, 1138–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safra, M.; Sas-Chen, A.; Nir, R.; Winkler, R.; Nachshon, A.; Bar-Yaacov, D.; Erlacher, M.; Rossmanith, W.; Stern-Ginossar, N.; Schwartz, S. The m1A landscape on cytosolic and mitochondrial mRNA at single-base resolution. Nature 2017, 551, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Xiong, X.; Zhang, M.; Wang, K.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, J.; Mao, Y.; Lv, J.; Yi, D.; Chen, X.-W.; et al. Base-Resolution Mapping Reveals Distinct m1A Methylome in Nuclear- and Mitochondrial-Encoded Transcripts. Mol. Cell 2017, 68, 993–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Rauch, S.; Dai, Q.; Cui, X.; Zhang, Z.; Nachtergaele, S.; Sepich, C.; He, C.; Dickinson, B.C. Evolution of a reverse transcriptase to map N1-methyladenosine in human messenger RNA. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 1281–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Kimsey, I.J.; Nikolova, E.N.; Sathyamoorthy, B.; Grazioli, G.; McSally, J.; Bai, T.; Wunderlich, C.H.; Kreutz, C.; Andricioaei, I.; et al. m1A and m1G disrupt A-RNA structure through the intrinsic instability of Hoogsteen base pairs. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016, 23, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alriquet, M.; Calloni, G.; Martínez-Limón, A.; Ponti, R.D.; Hanspach, G.; Hengesbach, M.; Tartaglia, G.G.; Vabulas, R.M. The protective role of m1A during stress-induced granulation. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 12, 870–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chujo, T.; Suzuki, T. Trmt61B is a methyltransferase responsible for 1-methyladenosine at position 58 of human mitochondrial tRNAs. RNA 2012, 18, 2269–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Wang, T.; Gonzalez, G.; Wang, Y. Identification of YTH Domain-Containing Proteins as the Readers for N1-Methyladenosine in RNA. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 6380–6384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubin, D.T.; Taylor, R.H. The methylation state of poly A-containing-messenger RNA from cultured hamster cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1975, 2, 1653–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.; Chen, W.; Liu, J.; Gu, N.; Zhang, R. Genome-wide identification of mRNA 5-methylcytosine in mammals. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2019, 26, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Squires, J.E.; Patel, H.R.; Nousch, M.; Sibbritt, T.D.; Humphreys, D.T.; Parker, B.J.; Suter, C.M.; Preiss, T. Widespread occurrence of 5-methylcytosine in human coding and non-coding RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 5023–5033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legrand, C.; Tuorto, F.; Hartmann, M.; Liebers, R.; Jacob, D.; Helm, M.; Lyko, F. Statistically robust methylation calling for whole-transcriptome bisulfite sequencing reveals distinct methylation patterns for mouse RNAs. Genome Res. 2017, 27, 1589–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajnic, M.; Alonso-Gil, S.; Polyansky, A.A.; de Ruiter, A.; Zagrovic, B. Interaction preferences between protein side chains and key epigenetic modifications 5-methylcytosine, 5-hydroxymethycytosine and N6-methyladenine. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, R.; Greene, P.J.; Santi, D.V. Exposition of a family of RNA m5C methyltransferases from searching genomic and proteomic sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999, 27, 3138–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goll, M.G.; Kirpekar, F.; Maggert, K.A.; Yoder, J.A.; Hsieh, C.-L.; Zhang, X.; Golic, K.G.; Jacobsen, S.E.; Bestor, T.H. Methylation of tRNA Asp by the DNA Methyltransferase Homolog Dnmt2. Science 2006, 311, 395–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selmi, T.; Hussain, S.; Dietmann, S.; Heiß, M.; Borland, K.; Flad, S.; Carter, J.-M.; Dennison, R.; Huang, Y.-L.; Kellner, S.; et al. Sequence- and structure-specific cytosine-5 mRNA methylation by NSUN6. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 49, 1006–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, Y. Dynamic transcriptomic m5C and its regulatory role in RNA processing. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2021, 12, e1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, Y.; Shi, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Gu, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Zhao, K.; Wang, C.; et al. Tet2 promotes pathogen infection-induced myelopoiesis through mRNA oxidation. Nature 2018, 554, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, X.; Tang, H.; Jiang, B.; Dou, Y.; Gorospe, M.; Wang, W. NSUN2-Mediated m5C Methylation and METTL3/METTL14-Mediated m6A Methylation Cooperatively Enhance p21 Translation. J. Cell. Biochem. 2017, 118, 2587–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Li, A.; Sun, B.-F.; Yang, Y.; Han, Y.-N.; Yuan, X.; Chen, R.-X.; Wei, W.-S.; Liu, Y.; Gao, C.-C.; et al. 5-methylcytosine promotes pathogenesis of bladder cancer through stabilizing mRNAs. Nature 2019, 21, 978–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Yang, Y.; Sun, B.-F.; Chen, Y.-S.; Xu, J.-W.; Lai, W.-Y.; Li, A.; Wang, X.; Bhattarai, D.P.; Xiao, W.; et al. 5-methylcytosine promotes mRNA export — NSUN2 as the methyltransferase and ALYREF as an m5C reader. Cell Res. 2017, 27, 606–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumann, U.; Zhang, H.-N.; Sibbritt, T.; Pan, A.; Horvath, A.; Gross, S.; Clark, S.J.; Yang, L.; Preiss, T. Multiple links between 5-methylcytosine content of mRNA and translation. BMC Biol. 2020, 18, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Yang, H.; Zhu, X.; Yadav, T.; Ouyang, J.; Truesdell, S.S.; Tan, J.; Wang, Y.; Duan, M.; Wei, L.; et al. m5C modification of mRNA serves a DNA damage code to promote homologous recombination. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Zhao, Y.; Li, L. Advances in RNA cytosine-5 methylation: detection, regulatory mechanisms, biological functions and links to cancer. Biomark. Res. 2020, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, S.M.; van Delft, P.; Mendil, L.; Bachman, M.; Smollett, K.; Werner, F.; Miska, E.A.; Balasubramanian, S. Formation and Abundance of 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine in RNA. ChemBioChem 2015, 16, 752–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, Y. Mechanisms and functions of Tet protein-mediated 5-methylcytosine oxidation. Minerva Anestesiol. 2011, 25, 2436–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Bashkenova, N.; Zang, R.; Huang, X.; Wang, J. The roles of TET family proteins in development and stem cells. Development 2020, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukrishnan, S.; Both, G.W.; Furuichi, Y.; Shatkin, A.J. 5′-Terminal 7-methylguanosine in eukaryotic mRNA is required for translation. Nature 1975, 255, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, K.; Park, P.; Manley, J. A nuclear micrococcal-sensitive, ATP-dependent exoribonuclease degrades uncapped but not capped RNA substratesx. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991, 19, 2685–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuichi, Y. Discovery of m7G-cap in eukaryotic mRNAs. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B 2015, 91, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowling, V.H. Regulation of mRNA cap methylation. Biochem. J. 2009, 425, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillutla, R.C.; Yue, Z.; Maldonado, E.; Shatkin, A.J. Recombinant Human mRNA Cap Methyltransferase Binds Capping Enzyme/RNA Polymerase IIo Complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 21443–21446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonatopoulos-Pournatzis, T.; Dunn, S.; Bounds, R.; Cowling, V.H. RAM/Fam103a1 Is Required for mRNA Cap Methylation. Mol. Cell 2011, 44, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaheen, R.; Abdel-Salam, G.M.H.; Guy, M.P.; Alomar, R.; Abdel-Hamid, M.S.; Afifi, H.H.; Ismail, S.I.; Emam, B.A.; Phizicky, E.M.; Alkuraya, F.S. Mutation in WDR4 impairs tRNA m7G46 methylation and causes a distinct form of microcephalic primordial dwarfism. Genome Biol. 2015, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrov, A.; Martzen, M.R.; Phizicky, E.M. Two proteins that form a complex are required for 7-methylguanosine modification of yeast tRNA. RNA 2002, 8, 1253–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haag, S.; Kretschmer, J.; Bohnsack, M.T. WBSCR22/Merm1 is required for late nuclear pre-ribosomal RNA processing and mediates N7-methylation of G1639 in human 18S rRNA. RNA 2014, 21, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leulliot, N.; Chaillet, M.; Durand, D.; Ulryck, N.; Blondeau, K.; van Tilbeurgh, H. Structure of the Yeast tRNA m7G Methylation Complex. Structure 2008, 16, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J.-M.; Ye, T.-T.; Ma, C.-J.; Lan, M.-D.; Liu, T.; Yuan, B.-F.; Feng, Y.-Q. Existence of Internal N7-Methylguanosine Modification in mRNA Determined by Differential Enzyme Treatment Coupled with Mass Spectrometry Analysis. ACS Chem. Biol. 2018, 13, 3243–3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-S.; Liu, C.; Ma, H.; Dai, Q.; Sun, H.-L.; Luo, G.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Hu, L.; Dong, X.; et al. Transcriptome-wide Mapping of Internal N7-Methylguanosine Methylome in Mammalian mRNA. Mol. Cell 2019, 74, 1304–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malbec, L.; Zhang, T.; Chen, Y.-S.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, B.-F.; Shi, B.-Y.; Zhao, Y.-L.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.-G. Dynamic methylome of internal mRNA N7-methylguanosine and its regulatory role in translation. Cell Res. 2019, 29, 927–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Qing, Y.; Dong, L.; Han, L.; Wu, D.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Xue, J.; Zhou, K.; Sun, M.; et al. QKI shuttles internal m7G-modified transcripts into stress granules and modulates mRNA metabolism. Cell 2023, 186, 3208–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandolfini, L.; Barbieri, I.; Bannister, A.J.; Hendrick, A.; Andrews, B.; Webster, N.; Murat, P.; Mach, P.; Brandi, R.; Robson, S.C.; et al. METTL1 Promotes let-7 MicroRNA Processing via m7G Methylation. Mol. Cell 2019, 74, 1278–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumas, L.; Herviou, P.; Dassi, E.; Cammas, A.; Millevoi, S. G-Quadruplexes in RNA Biology: Recent Advances and Future Directions. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2020, 46, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, I.; Popenda. ; Sarzyńska, J.; Małgowska, M.; Lahiri, A.; Gdaniec, Z.; Kierzek, R. Computational and NMR studies of RNA duplexes with an internal pseudouridine-adenosine base pair. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, K.; Bellodi, C.; Landry, D.M.; Niederer, R.O.; Meskauskas, A.; Musalgaonkar, S.; Kopmar, N.; Krasnykh, O.; Dean, A.M.; Thompson, S.R.; et al. rRNA Pseudouridylation Defects Affect Ribosomal Ligand Binding and Translational Fidelity from Yeast to Human Cells. Mol. Cell 2011, 44, 660–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, P.; Adachi, H.; Yu, Y.-T. Spliceosomal snRNA Epitranscriptomics. Front. Genet. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlile, T.M.; Rojas-Duran, M.F.; Zinshteyn, B.; Shin, H.; Bartoli, K.M.; Gilbert, W.V. Pseudouridine profiling reveals regulated mRNA pseudouridylation in yeast and human cells. Nature 2014, 515, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karijolich, J.; Yu, Y.-T. Converting nonsense codons into sense codons by targeted pseudouridylation. Nature 2011, 474, 395–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhao, X.; Kierzek, R.; Yu, Y.-T. A Flexible RNA Backbone within the Polypyrimidine Tract Is Required for U2AF65 Binding and Pre-mRNA Splicing InVivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010, 30, 4108–4119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, N.M.; Su, A.; Burns, M.C.; Nussbacher, J.K.; Schaening, C.; Sathe, S.; Yeo, G.W.; Gilbert, W.V. Pseudouridine synthases modify human pre-mRNA co-transcriptionally and affect pre-mRNA processing. Mol. Cell 2022, 82, 645–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bykhovskaya, Y.; Casas, K.; Mengesha, E.; Inbal, A.; Fischel-Ghodsian, N. Missense Mutation in Pseudouridine Synthase 1 (PUS1) Causes Mitochondrial Myopathy and Sideroblastic Anemia (MLASA). Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004, 74, 1303–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitrova, D.G.; Teysset, L.; Carré, C. RNA 2’-O-Methylation (Nm) Modification in Human Diseases. Genes 2019, 10, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monaco, P.L.; Marcel, V.; Diaz, J.-J.; Catez, F. 2′-O-Methylation of Ribosomal RNA: Towards an Epitranscriptomic Control of Translation? Biomolecules 2018, 8, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decatur, W.A.; Fournier, M.J. rRNA modifications and ribosome function. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2002, 27, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachmani, D.; Bothmer, A.H.; Grisendi, S.; Mele, A.; Bothmer, D.; Lee, J.D.; Monteleone, E.; Cheng, K.; Zhang, Y.; Bester, A.C.; et al. Germline NPM1 mutations lead to altered rRNA 2′-O-methylation and cause dyskeratosis congenita. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 1518–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Marchand, V.; Motorin, Y.; Lafontaine, D.L.J. Identification of sites of 2′-O-methylation vulnerability in human ribosomal RNAs by systematic mapping. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, M.L.; Crary, S.M.; Jackman, J.E.; Grayhack, E.J.; Phizicky, E.M. The 2′-O-methyltransferase responsible for modification of yeast tRNA at position 4. RNA 2007, 13, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endres, L.; Rose, R.E.; Doyle, F.; Rahn, T.; Lee, B.; Seaman, J.; McIntyre, W.D.; Fabris, D. 2'-O-ribose methylation of transfer RNA promotes recovery from oxidative stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0229103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard-Jean, F.; Brand, C.; Tremblay-Létourneau, M.; Allaire, A.; Beaudoin, M.C.; Boudreault, S.; Duval, C.; Rainville-Sirois, J.; Robert, F.; Pelletier, J.; et al. 2'-O-methylation of the mRNA cap protects RNAs from decapping and degradation by DXO. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0193804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Moshitch-Moshkovitz, S.; Han, D.; Kol, N.; Amariglio, N.; Rechavi, G.; Dominissini, D.; He, C. Nm-seq maps 2′-O-methylation sites in human mRNA with base precision. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 695–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.; Indrisiunaite, G.; DeMirci, H.; Ieong, K.-W.; Wang, J.; Petrov, A.; Prabhakar, A.; Rechavi, G.; Dominissini, D.; He, C.; et al. 2′-O-methylation in mRNA disrupts tRNA decoding during translation elongation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2018, 25, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, B.A.; Ho, H.-T.; Ranganathan, S.V.; Vangaveti, S.; Ilkayeva, O.; Assi, H.A.; Choi, A.K.; Agris, P.F.; Holley, C.L. Modification of messenger RNA by 2′-O-methylation regulates gene expression in vivo. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, F.; Stepinski, J.; Darzynkiewicz, E.; Pelletier, J. Characterization of hMTr1, a Human Cap1 2′-O-Ribose Methyltransferase*. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 33037–33044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, M.; Purta, E.; Kaminska, K.H.; Cymerman, I.A.; Campbell, D.A.; Mittra, B.; Zamudio, J.R.; Sturm, N.R.; Jaworski, J.; Bujnicki, J.M. 2′-O-ribose methylation of cap2 in human: function and evolution in a horizontally mobile family. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 4756–4768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, L.M.; Wallis, S.C.; Pease, R.J.; Edwards, Y.H.; Knott, T.J.; Scott, J. A novel form of tissue-specific RNA processing produces apolipoprotein-B48 in intestine. Cell 1987, 50, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.C.; Bennett, R.P.; Kizilyer, A.; McDougall, W.M.; Prohaska, K.M. Functions and regulation of the APOBEC family of proteins. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2012, 23, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B. A developmentally regulated activity that unwinds RNA duplexes. Cell 1987, 48, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keegan, L.P.; McGurk, L.; Palavicini, J.P.; Brindle, J.; Paro, S.; Li, X.; Rosenthal, J.J.C.; O'Connell, M.A. Functional conservation in human and Drosophila of Metazoan ADAR2 involved in RNA editing: loss of ADAR1 in insects. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 7249–7262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavov, D.; Crnogorac-Jurčević, T.; Clark, M.; Gardiner, K. Comparative analysis of the DRADA A-to-I RNA editing gene from mammals, pufferfish and zebrafish. Gene 2000, 250, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.D.; Kim, T.T.; Walsh, T.; Kobayashi, Y.; Matise, T.C.; Buyske, S.; Gabriel, A. Widespread RNA Editing of Embedded Alu Elements in the Human Transcriptome. Genome Res. 2004, 14, 1719–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.H.; GTEx Consortium; Li, Q.; Shanmugam, R.; Piskol, R.; Kohler, J.; Young, A.N.; Liu, K.I.; Zhang, R.; Ramaswami, G.; et al. Dynamic landscape and regulation of RNA editing in mammals. Nature 2017, 550, 249–254. [CrossRef]

- Nishikura, K. A-to-I editing of coding and non-coding RNAs by ADARs. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 17, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazloomian, A.; Meyer, I.M. Genome-wide identification and characterization of tissue-specific RNA editing events inD. melanogasterand their potential role in regulating alternative splicing. RNA Biol. 2015, 12, 1391–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, T.; Park, C.-K.; Leung, A.K.; Gao, Y.; Hyde, T.M.; Kleinman, J.E.; Rajpurohit, A.; Tao, R.; Shin, J.H.; Weinberger, D.R. Dynamic regulation of RNA editing in human brain development and disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2016, 19, 1093–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntley, M.A.; Lou, M.; Goldstein, L.D.; Lawrence, M.; Dijkgraaf, G.J.P.; Kaminker, J.S.; Gentleman, R. Complex regulation of ADAR-mediated RNA-editing across tissues. BMC Genom. 2016, 17, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlstedt, H.; Daniel, C.; Ensterö, M.; Öhman, M. Large-scale mRNA sequencing determines global regulation of RNA editing during brain development. Genome Res. 2009, 19, 978–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakes, E.; Anderson, A.; Cohen-Gadol, A.; Hundley, H.A. Adenosine Deaminase That Acts on RNA 3 (ADAR3) Binding to Glutamate Receptor Subunit B Pre-mRNA Inhibits RNA Editing in Glioblastoma. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 4326–4335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Xiao, X. Genome sequence–independent identification of RNA editing sites. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 347–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Tan, B.C.; Kang, L.; Tian, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Liang, Y.; Hu, X.; Tan, X.; et al. Comprehensive analysis of RNA-Seq data reveals extensive RNA editing in a human transcriptome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel, C.; Lagergren, J.; Öhman, M. RNA editing of non-coding RNA and its role in gene regulation. Biochimie 2015, 117, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggington, J.M.; Greene, T.; Bass, B.L. Predicting sites of ADAR editing in double-stranded RNA. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, J.-F.; Yang, Q.; Liu, C.-X.; Wu, M.; Chen, L.-L.; Yang, L. N6-Methyladenosines Modulate A-to-I RNA Editing. Mol. Cell 2018, 69, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueter, S.M.; Dawson, T.R.; Emeson, R.B. Regulation of alternative splicing by RNA editing. Nature 1999, 399, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brümmer, A.; Yang, Y.; Chan, T.W.; Xiao, X. Structure-mediated modulation of mRNA abundance by A-to-I editing. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geula, S.; Moshitch-Moshkovitz, S.; Dominissini, D.; Mansour, A.A.F.; Kol, N.; Salmon-Divon, M.; Hershkovitz, V.; Peer, E.; Mor, N.; Manor, Y.S.; et al. M6A MRNA Methylation Facilitates Resolution of Naïve Pluripotency toward Differentiation. Science (1979) 2015, 347, 1002–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Batista, P.J.; Molinie, B.; Wang, J.; Qu, K.; Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Bouley, D.M.; Lujan, E.; Haddad, B.; Daneshvar, K.; et al. m6A RNA Modification Controls Cell Fate Transition in Mammalian Embryonic Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 15, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Toth, J.I.; Petroski, M.D.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, J.C. N6-methyladenosine modification destabilizes developmental regulators in embryonic stem cells. Nature 2014, 16, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendel, M.; Chen, K.-M.; Homolka, D.; Gos, P.; Pandey, R.R.; McCarthy, A.A.; Pillai, R.S. Methylation of Structured RNA by the m6A Writer METTL16 Is Essential for Mouse Embryonic Development. Mol. Cell 2018, 71, 986–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yue, M.; Wang, J.; Kumar, S.; Wechsler-Reya, R.J.; Zhang, Z.; Ogawa, Y.; Kellis, M.; Duester, G.; et al. N6-methyladenosine RNA modification regulates embryonic neural stem cell self-renewal through histone modifications. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilo, F.; Zhang, F.; Sancho, A.; Fidalgo, M.; Di Cecilia, S.; Vashisht, A.; Lee, D.-F.; Chen, C.-H.; Rengasamy, M.; Andino, B.; et al. Coordination of m 6 A mRNA Methylation and Gene Transcription by ZFP217 Regulates Pluripotency and Reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell 2015, 17, 689–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Pei, Y.; Zhou, R.; Tang, Z.; Yang, Y. Regulation of RNA N6-methyladenosine modification and its emerging roles in skeletal muscle development. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 17, 1682–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, B.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Mu, T.; Feng, X.; Ma, R.; Gu, Y. Regulatory role of RNA N6-methyladenosine modifications during skeletal muscle development. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 929183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yao, Y.; Han, J.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Tang, Z.; Gao, F. Longitudinal epitranscriptome profiling reveals the crucial role of N6-methyladenosine methylation in porcine prenatal skeletal muscle development. J. Genet. Genom. 2020, 47, 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Xu, Z.; Lu, L.; Zeng, T.; Gu, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yang, P.; Wen, Y.; Lin, D.; et al. Transcriptome-wide study revealed m6A regulation of embryonic muscle development in Dingan goose (Anser cygnoides orientalis). BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, K.; Fan, Y.; Liang, Y.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, G.; Deng, M.; Wang, Z.; Lu, J.; Shi, J.; Wang, F.; et al. FTO-mediated demethylation of GADD45B promotes myogenesis through the activation of p38 MAPK pathway. Mol. Ther. - Nucleic Acids 2021, 26, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Liu, S.; Zhang, W.; Xiong, T.; Zhou, M.; Hu, X.; Mao, H.; Liu, S. Profiling Analysis of N6-Methyladenosine mRNA Methylation Reveals Differential m6A Patterns during the Embryonic Skeletal Muscle Development of Ducks. Animals 2022, 12, 2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huang, N.; Yang, M.; Wei, D.; Tai, H.; Han, X.; Gong, H.; Zhou, J.; Qin, J.; Wei, X.; et al. FTO is required for myogenesis by positively regulating mTOR-PGC-1α pathway-mediated mitochondria biogenesis. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e2702–e2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Deng, R.; Zhang, K.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, J. Single-Cell Imaging of m 6 A Modified RNA Using m 6 A-Specific In Situ Hybridization Mediated Proximity Ligation Assay (m 6 AISH-PLA). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 22646–22651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.N.; Chen, Y.; Wei, Y.Y.; Raza, M.A.; Zou, Q.; Xi, X.Y.; Zhu, L.; Tang, G.Q.; Jiang, Y.Z.; Li, X.W. Regulation of m6A RNA Methylation and Its Effect on Myogenic Differentiation in Murine Myoblasts. Mol. Biol. 2019, 53, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheller, B.J.; Blum, J.E.; Fong, E.H.H.; Malysheva, O.V.; Cosgrove, B.D.; Thalacker-Mercer, A.E. A defined N6-methyladenosine (m6A) profile conferred by METTL3 regulates muscle stem cell/myoblast state transitions. Cell Death Discov. 2020, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Mei, C.; Ma, X.; Du, J.; Wang, J.; Zan, L. M6 A Methylases Regulate Myoblast Proliferation, Apoptosis and Differentiation. Animals 2022, 12, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Wu, S.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Tang, Z.; Gao, F. Coordinated transcriptional and post-transcriptional epigenetic regulation during skeletal muscle development and growth in pigs. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Shin, Y.-H.; Li, M.; Wang, F.; Tong, Q.; Zhang, P. The Fat Mass and Obesity Associated Gene FTO Functions in the Brain to Regulate Postnatal Growth in Mice. PLOS ONE 2010, 5, e14005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, C.; Moir, L.; McMurray, F.; Girard, C.; Banks, G.T.; Teboul, L.; Wells, S.; Brüning, J.C.; Nolan, P.M.; Ashcroft, F.M.; et al. Overexpression of Fto leads to increased food intake and results in obesity. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 1086–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.J.; Lei, H.; Yang, B.; Diao, L.T.; Liao, J.Y.; He, J.H.; Tao, S.; Hu, Y.X.; Hou, Y.R.; Sun, Y.J.; et al. Dynamic M6A MRNA Methylation Reveals the Role of METTL3/14-M6A-MNK2-ERK Signaling Axis in Skeletal Muscle Differentiation and Regeneration. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudou, K.; Komatsu, T.; Nogami, J.; Maehara, K.; Harada, A.; Saeki, H.; Oki, E.; Maehara, Y.; Ohkawa, Y. The requirement of Mettl3-promoted MyoD mRNA maintenance in proliferative myoblasts for skeletal muscle differentiation. Open Biol. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Han, H.; Xiong, Q.; Yang, C.; Wang, L.; Ma, J.; Lin, S.; Jiang, Y.-Z. METTL3-Mediated m6A Methylation Regulates Muscle Stem Cells and Muscle Regeneration by Notch Signaling Pathway. Stem Cells Int. 2021, 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brack, A.S.; Conboy, I.M.; Conboy, M.J.; Shen, J.; Rando, T.A. A Temporal Switch from Notch to Wnt Signaling in Muscle Stem Cells Is Necessary for Normal Adult Myogenesis. Cell Stem Cell 2008, 2, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Ning, Y.; Raza, S.H.A.; Mei, C.; Zan, L. MEF2C Expression Is Regulated by the Post-transcriptional Activation of the METTL3-m6A-YTHDF1 Axis in Myoblast Differentiation. Front. Veter- Sci. 2022, 9, 900924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diao, L.-T.; Xie, S.-J.; Lei, H.; Qiu, X.-S.; Huang, M.-C.; Tao, S.; Hou, Y.-R.; Hu, Y.-X.; Sun, Y.-J.; Zhang, Q.; et al. METTL3 regulates skeletal muscle specific miRNAs at both transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 552, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.-J.; Tao, S.; Diao, L.-T.; Li, P.-L.; Chen, W.-C.; Zhou, Z.-G.; Hu, Y.-X.; Hou, Y.-R.; Lei, H.; Xu, W.-Y.; et al. Characterization of Long Non-coding RNAs Modified by m6A RNA Methylation in Skeletal Myogenesis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrosino, J.M.; Hinger, S.A.; Golubeva, V.A.; Barajas, J.M.; Dorn, L.E.; Iyer, C.C.; Sun, H.-L.; Arnold, W.D.; He, C.; Accornero, F. The m6A methyltransferase METTL3 regulates muscle maintenance and growth in mice. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Lu, M.; Liu, D.; Shi, Y.; Ren, J.; Wang, S.; Jing, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, Q.; Li, H.; et al. m6A epitranscriptomic regulation of tissue homeostasis during primate aging. Nat. Aging 2023, 3, 705–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, T.; Wang, Q.; Fu, R.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, N.; Li, Z.; Gao, G.; Peng, S.; Yang, D. m6A demethylase ALKBH5 drives denervation-induced muscle atrophy by targeting HDAC4 to activate FoxO3 signalling. J. Cachex- Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 1210–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, S.; Kurowski, A.; Nichols, J.; Watt, F.M.; Benitah, S.A.; Frye, M. The RNA–Methyltransferase Misu (NSun2) Poises Epidermal Stem Cells to Differentiate. PLOS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trixl, L.; Amort, T.; Wille, A.; Zinni, M.; Ebner, S.; Hechenberger, C.; Eichin, F.; Gabriel, H.; Schoberleitner, I.; Huang, A.; et al. RNA cytosine methyltransferase Nsun3 regulates embryonic stem cell differentiation by promoting mitochondrial activity. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2017, 75, 1483–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, S.; Bandiera, R.; Popis, M.; Hussain, S.; Lombard, P.; Aleksic, J.; Sajini, A.; Tanna, H.; Cortés-Garrido, R.; Gkatza, N.; et al. Stem cell function and stress response are controlled by protein synthesis. Nature 2016, 534, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benarroch, L.; Bonne, G.; Rivier, F.; Hamroun, D. The 2023 version of the gene table of neuromuscular disorders (nuclear genome). Neuromuscul. Disord. 2022, 33, 76–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdasco, M.; Esteller, M. Towards a druggable epitranscriptome: Compounds that target RNA modifications in cancer. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 179, 2868–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Han, H.; Xiong, Q.; Yang, C.; Wang, L.; Ma, J.; Lin, S.; Jiang, Y.-Z. METTL3-Mediated m6A Methylation Regulates Muscle Stem Cells and Muscle Regeneration by Notch Signaling Pathway. Stem Cells Int. 2021, 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adachi, H.; Hengesbach, M.; Yu, Y.-T.; Morais, P. From Antisense RNA to RNA Modification: Therapeutic Potential of RNA-Based Technologies. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rugowska, A.; Starosta, A.; Konieczny, P. Epigenetic modifications in muscle regeneration and progression of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Clin. Epigenetics 2021, 13, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caretti, G.; DI Padova, M.; Micales, B.; Lyons, G.E.; Sartorelli, V. The Polycomb Ezh2 methyltransferase regulates muscle gene expression and skeletal muscle differentiation. Genes Dev. 2004, 18, 2627–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, S. Step aside CRISPR, RNA editing is taking off. Nature 2020, 578, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeshima, Y.; Yagi, M.; Okizuka, Y.; Awano, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yamauchi, Y.; Nishio, H.; Matsuo, M. Mutation spectrum of the dystrophin gene in 442 Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy cases from one Japanese referral center. J. Hum. Genet. 2010, 55, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulco, M.; Schiltz, R.L.; Iezzi, S.; King, M.T.; Zhao, P.; Kashiwaya, Y.; Hoffman, E.; Veech, R.L.; Sartorelli, V. Sir2 Regulates Skeletal Muscle Differentiation as a Potential Sensor of the Redox State. Mol. Cell 2003, 12, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, S.; Imbriano, C.; Moresi, V.; Renzini, A.; Belluti, S.; Lozanoska-Ochser, B.; Gigli, G.; Cedola, A. Histone deacetylase functions and therapeutic implications for adult skeletal muscle metabolism. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, Y.S.; Kuno, A.; Hosoda, R.; Tanno, M.; Miura, T.; Shimamoto, K.; Horio, Y. Resveratrol Ameliorates Muscular Pathology in the Dystrophic mdx Mouse, a Model for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Experiment 2011, 338, 784–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonkin, J.; Villarroya, F.; Puri, P.L.; Vinciguerra, M. SIRT1 signaling as potential modulator of skeletal muscle diseases. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2012, 12, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marroncelli, N.; Bianchi, M.; Bertin, M.; Consalvi, S.; Saccone, V.; De Bardi, M.; Puri, P.L.; Palacios, D.; Adamo, S.; Moresi, V. HDAC4 regulates satellite cell proliferation and differentiation by targeting P21 and Sharp1 genes. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moresi, V.; Williams, A.H.; Meadows, E.; Flynn, J.M.; Potthoff, M.J.; McAnally, J.; Shelton, J.M.; Backs, J.; Klein, W.H.; Richardson, J.A.; et al. Myogenin and Class II HDACs Control Neurogenic Muscle Atrophy by Inducing E3 Ubiquitin Ligases. Cell 2010, 143, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pigna, E.; Renzini, A.; Greco, E.; Simonazzi, E.; Fulle, S.; Mancinelli, R.; Moresi, V.; Adamo, S. HDAC4 preserves skeletal muscle structure following long-term denervation by mediating distinct cellular responses. Skelet. Muscle 2018, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigna, E.; Simonazzi, E.; Sanna, K.; Bernadzki, K.M.; Proszynski, T.; Heil, C.; Palacios, D.; Adamo, S.; Moresi, V. Histone deacetylase 4 protects from denervation and skeletal muscle atrophy in a murine model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. EBioMedicine 2019, 40, 717–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzini, A.; Pigna, E.; Rocchi, M.; Cedola, A.; Gigli, G.; Moresi, V.; Coletti, D. Sex and HDAC4 Differently Affect the Pathophysiology of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis in SOD1-G93A Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzini, A.; Marroncelli, N.; Cavioli, G.; Di Francescantonio, S.; Forcina, L.; Lambridis, A.; Di Giorgio, E.; Valente, S.; Mai, A.; Brancolini, C.; et al. Cytoplasmic HDAC4 regulates the membrane repair mechanism in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J. Cachex- Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 1339–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Xie, K.; Li, M.; Yang, Q.; Wang, X. N6-methyladenosine (m6A) methyltransferase METTL3 regulates sepsis-induced myocardial injury through IGF2BP1/HDAC4 dependent manner. Cell Death Discov. 2022, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.V.; Hughes, S.M. Mef2 and the skeletal muscle differentiation program. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017, 72, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakka, K.; Ghigna, C.; Gabellini, D.; Dilworth, F.J. Diversification of the muscle proteome through alternative splicing. Skelet. Muscle 2018, 8, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Ramachandran, B.; Gulick, T. Alternative Pre-mRNA Splicing Governs Expression of a Conserved Acidic Transactivation Domain in Myocyte Enhancer Factor 2 Factors of Striated Muscle and Brain. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 28749–28760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebastian, S.; Faralli, H.; Yao, Z.; Rakopoulos, P.; Palii, C.; Cao, Y.; Singh, K.; Liu, Q.-C.; Chu, A.; Aziz, A.; et al. Tissue-specific splicing of a ubiquitously expressed transcription factor is essential for muscle differentiation. Genes Dev. 2013, 27, 1247–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baruffaldi, F.; Montarras, D.; Basile, V.; De Feo, L.; Badodi, S.; Ganassi, M.; Battini, R.; Nicoletti, C.; Imbriano, C.; Musarò, A.; et al. Dynamic Phosphorylation of the Myocyte Enhancer Factor 2Cα1 Splice Variant Promotes Skeletal Muscle Regeneration and Hypertrophy. STEM CELLS 2016, 35, 725–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganassi, M.; Badodi, S.; Polacchini, A.; Baruffaldi, F.; Battini, R.; Hughes, S.; Hinits, Y.; Molinari, S. Distinct functions of alternatively spliced isoforms encoded by zebrafish mef2ca and mef2cb. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Gene Regul. Mech. 2014, 1839, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yogev, O.; Williams, V.C.; Hinits, Y.; Hughes, S.M. eIF4EBP3L Acts as a Gatekeeper of TORC1 In Activity-Dependent Muscle Growth by Specifically Regulating Mef2ca Translational Initiation. PLOS Biol. 2013, 11, e1001679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, B.L.; Lu, J.; Olson, E.N. The MEF2A 3′ Untranslated Region Functions as a cis-Acting Translational Repressor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997, 17, 2756–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Ning, Y.; Raza, S.H.A.; Mei, C.; Zan, L. MEF2C Expression Is Regulated by the Post-transcriptional Activation of the METTL3-m6A-YTHDF1 Axis in Myoblast Differentiation. Front. Veter- Sci. 2022, 9, 900924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, W.; Luo, W.; Liu, S.; Jiang, H.; Liu, S.; Xu, J.; Chen, B. Cloning of the RNA m6A Methyltransferase 3 and Its Impact on the Proliferation and Differentiation of Quail Myoblasts. Veter- Sci. 2023, 10, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlile, T.M.; Rojas-Duran, M.F.; Zinshteyn, B.; Shin, H.; Bartoli, K.M.; Gilbert, W.V. Pseudouridine profiling reveals regulated mRNA pseudouridylation in yeast and human cells. Nature 2014, 515, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, H.; De Zoysa, M.D.; Yu, Y.-T. Post-transcriptional pseudouridylation in mRNA as well as in some major types of noncoding RNAs. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Gene Regul. Mech. 2018, 1862, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Smigiel, R.; Kuzniewska, B.; Chmielewska, J.J.; Kosińska, J.; Biela, M.; Biela, A.; Kościelniak, A.; Dobosz, D.; Laczmanska, I.; et al. Destabilization of mutated human PUS3 protein causes intellectual disability. Hum. Mutat. 2022, 43, 2063–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaheen, R.; Tasak, M.; Maddirevula, S.; Abdel-Salam, G.M.H.; Sayed, I.S.M.; Alazami, A.M.; Al-Sheddi, T.; Alobeid, E.; Phizicky, E.M.; Alkuraya, F.S. PUS7 mutations impair pseudouridylation in humans and cause intellectual disability and microcephaly. Hum. Genet. 2019, 138, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, N.M.; Su, A.; Burns, M.C.; Nussbacher, J.K.; Schaening, C.; Sathe, S.; Yeo, G.W.; Gilbert, W.V. Pseudouridine synthases modify human pre-mRNA co-transcriptionally and affect pre-mRNA processing. Mol. Cell 2022, 82, 645–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachinski, L.L.; Sirito, M.; Böhme, M.; Baggerly, K.A.; Udd, B.; Krahe, R. Altered MEF2 isoforms in myotonic dystrophy and other neuromuscular disorders. Muscle Nerve 2010, 42, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timchenko, N.A.; Patel, R.; Iakova, P.; Cai, Z.-J.; Quan, L.; Timchenko, L.T. Overexpression of CUG Triplet Repeat-binding Protein, CUGBP1, in Mice Inhibits Myogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 13129–13139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-S.; Cao, Y.; Witwicka, H.E.; Tom, S.; Tapscott, S.J.; Wang, E.H. RNA-binding Protein Muscleblind-like 3 (MBNL3) Disrupts Myocyte Enhancer Factor 2 (Mef2) β-Exon Splicing. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 33779–33787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, V.; Baruffaldi, F.; Dolfini, D.; Belluti, S.; Benatti, P.; Ricci, L.; Artusi, V.; Tagliafico, E.; Mantovani, R.; Molinari, S.; et al. NF-YA splice variants have different roles on muscle differentiation. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Gene Regul. Mech. 2016, 1859, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigillo, G.; Basile, V.; Belluti, S.; Ronzio, M.; Sauta, E.; Ciarrocchi, A.; Latella, L.; Saclier, M.; Molinari, S.; Vallarola, A.; et al. The transcription factor NF-Y participates to stem cell fate decision and regeneration in adult skeletal muscle. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libetti, D.; Bernardini, A.; Sertic, S.; Messina, G.; Dolfini, D.; Mantovani, R. The Switch from NF-YAl to NF-YAs Isoform Impairs Myotubes Formation. Cells 2020, 9, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigillo, G.; Belluti, S.; Campani, V.; Ragazzini, G.; Ronzio, M.; Miserocchi, G.; Bighi, B.; Cuoghi, L.; Mularoni, V.; Zappavigna, V.; et al. The NF–Y splicing signature controls hybrid EMT and ECM-related pathways to promote aggressiveness of colon cancer. Cancer Lett. 2023, 567, 216262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belluti, S.; Semeghini, V.; Rigillo, G.; Ronzio, M.; Benati, D.; Torricelli, F.; Bonetti, L.R.; Carnevale, G.; Grisendi, G.; Ciarrocchi, A.; et al. Alternative splicing of NF-YA promotes prostate cancer aggressiveness and represents a new molecular marker for clinical stratification of patients. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basile, V.; Baruffaldi, F.; Dolfini, D.; Belluti, S.; Benatti, P.; Ricci, L.; Artusi, V.; Tagliafico, E.; Mantovani, R.; Molinari, S.; et al. NF-YA splice variants have different roles on muscle differentiation. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Gene Regul. Mech. 2016, 1859, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigillo, G.; Basile, V.; Belluti, S.; Ronzio, M.; Sauta, E.; Ciarrocchi, A.; Latella, L.; Saclier, M.; Molinari, S.; Vallarola, A.; et al. The transcription factor NF-Y participates to stem cell fate decision and regeneration in adult skeletal muscle. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, I.; Tzelepis, K.; Pandolfini, L.; Shi, J.; Millán-Zambrano, G.; Robson, S.C.; Aspris, D.; Migliori, V.; Bannister, A.J.; Han, N.; et al. Promoter-bound METTL3 maintains myeloid leukaemia by m6A-dependent translation control. Nature 2017, 552, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, N.D.; Soroka, A.; Klose, A.; Liu, W.; Chakkalakal, J.V. Smad4 restricts differentiation to promote expansion of satellite cell derived progenitors during skeletal muscle regeneration. Abstract 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forouhan, M.; Lim, W.F.; Zanetti-Domingues, L.C.; Tynan, C.J.; Roberts, T.C.; Malik, B.; Manzano, R.; Speciale, A.A.; Ellerington, R.; Garcia-Guerra, A.; et al. AR cooperates with SMAD4 to maintain skeletal muscle homeostasis. Acta Neuropathol. 2022, 143, 713–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).