1. Introduction

Traditional industrial area construction relies on a variety of natural resources, such as coal, steel, and oil. In these sprawling domains, large isolated industrial plants and enterprise compound with various medical services, basic supporting facilities, and industrial workplaces represent these regions [

26]. With the development of the world economy from industrialization to post-industrialization, many traditional industrial areas have experienced a long-term economic depression, gradually declining due to several issues, such as economic structure adjustment, single industrial structure, and resource depletion [

16]. A worldwide challenge is transforming these abandoned industrial areas. With the traditional industrial areas’ production functions gradually disappearing, rich industrial heritages benefit the development of industrial tourism [

15]. Industrial buildings and squares can provide unique cultural elements and spatial resources for leisure, entertainment, and arts development in urban cities, becoming a strategic solution for those industrial areas, such as industrial theme parks and museums [

13]. Countries all over the world have prioritized abandoned industrial sites for policy support and promoted tourism development, such as Colombia in Latin America, Busan in South Korea, Carlsberg Brewery in Denmark, Turin in Italy, and Cologne in Germany [3, 22, 14]. As a result, the transformation of industrial areas for tourism promotes the optimization of regional economic and industrial structure, solutions for social employment, improvement of the ecological environment, and the continuation of industrial culture [37, 39].

However, the transformation of tourism development brings significant challenges regarding gentrification. Gentrification (gentry), coined by Glass [

10], explains the process of the middle class returning from the decaying city to the rural areas and transforming the living space of low-income people, which triggers the change of class of population and space of community. Later, this concept has been developed in various contexts. For example, super gentrification describes the phenomenon of the high-income class replacing the blue-and-white collar workers in urban central areas [

28]. Rural gentrification demonstrates the process of the middle class moving into rural areas in pursuit of living in comfort and leisure, which leads local people to leave, eventually transforming the class [

36]. With tourism development and globalization, tourism gentrification has become a social trend, resulting in severe local and residential issues [

30]. In terms of traditional industrial regions, gentrification is a process of revitalization of abandonment and deterioration, which is a widespread phenomenon in the field of geography and sociology [

46]. The growing impact of industrial tourism and subsequent gentrification as a global trend creates complex challenges for local communities and residential areas.

Tourism gentrification refers to the process of changing areas from middle-class neighborhoods to wealthy and exclusive places driven by the development of tourism and entertainment [

12]. Scholars look at the concept of tourism gentrification along multiple facets. From the tourists’ aspect, touristification represents the process of creating spaces tailored to tourist lifestyles [

8]. From a marketing standpoint, commercial gentrification is regarded as the replacement of independent and local businesses with national or international tourism-related chain stores and upscale facilities [

48]. However, residents should be emphasized as an important role in tourism gentrification [

53]. The impact of tourism gentrification on residents is profound, as it can lead to demographic, economic, and sociocultural transformations that critically affect residents' lifestyles, which currently remain underexplored in the literature.

Tourism gentrification in urban areas is developed by replying to three types of sites: historical and cultural monuments, landscapes, and abandoned industrial sites [

52]. Historical and cultural monuments mainly appear with relatively rich historical and cultural resources. It is developed by building tourism attractions of historical blocks and cultural aesthetics, combining business activities with residents' lives. The second type can be divided into natural and artificial landscapes. Natural landscapes refer to the attractions of existing natural resources to drive regional development. Humans create artificial landscapes by integrating infrastructures with environmental elements. Lastly, the revival of abandoned industrial sites is various, such as remodeling industrial infrastructure, establishing convenient transportation, and enhancing entertainment facilities. The growing industrial tourism drives positive outcomes for public and private actors and enhances the sustainable goal in post-industrial tourism [

23]. However, previous studies about tourism gentrification have primarily focused on the first two types of attractions, historical monuments and landscapes [31, 34, 44, 47]. Thus, creating a gap in tourism gentrification in the context of traditional industrial areas, especially for the residents who previously worked in the industry as hosts and now found themselves marginalized in the process of tourism gentrification. Therefore, understanding their feelings and opinions toward the impacts of tourism gentrification is crucial.

The stress threshold theory explains the phenomenon of how residential relocations occur when the stress from the living environment exceeds the threshold of residents’ tolerance [

50]. Based on the stress threshold theory, this study investigates how tourism gentrification affects residents’ stress to make migration decisions. Q methodology is employed to overcome the limitations of both quantitative and qualitative methods and support small sample sizes, but few studies have employed this method [17, 27, 49]. Due to the difficulty of data collection during the pandemic, Q methodology is an effective and appropriate method to develop a framework to understand residents’ perceptions of tourism gentrification in traditional industrial areas. The 798 Art Zone in Beijing, China, a symbolic example of tourism development integrating industrial heritage with arts and fashion in traditional industrial areas, is the focus of this study. Therefore, this study aims to 1) investigate the patterns of residents’ stress caused by tourism gentrification in the 798 Art Zone and 2) provide a conceptual framework to elucidate the impact of tourism gentrification on residents’ decisions to relocate in traditional industrial areas. This study contributes to the knowledge of tourism gentrification in the context of traditional industrial areas from residents’ perspectives. This study also provides practical guidance for solving the conflicts between visitors and residents and promoting sustainable industrial tourism development.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Tourism Gentrification in Traditional Industrial Areas

Tourism gentrification, a distinctive form, is primarily characterized by its labor-intensive nature [

29]. Tourism development requires a substantial workforce of service practitioners and managers, attracting a number of migrant workers to engage in the tourism sector. This type of tourism could result in the touristification of local businesses and activities [

48]. The complex characteristics of people flow, logistics, and capital within the process of tourism gentrification determine that the role of tourism gentrification is not only limited to the neighborhood but also involves the broader regions [

24]. Tourism in traditional industrial areas intertwines with other consumption and production processes, blurring distinctions between visitor-centric and local community spaces. Thus, tourism gentrification in traditional industrial areas has become increasingly complicated. Tourism transformation in traditional industrial areas has fundamentally altered the utilization of buildings and spaces [

54]. These industrial areas, formerly dedicated to residents' daily work and life, are progressively transitioning towards privatization and catering primarily to tourism. Therefore, we argue that the conceptualization of tourism gentrification in traditional industrial regions should take into account the transformation of the spatial functions and attributes of the industrial heritage, as well as the indigenous identity and culture of residents and migration workers.

Some scholars have explored the concept of tourism gentrification as it affects historical and cultural districts and rural tourism [5, 11, 20]. However, characteristics differ between historical and rural areas and traditional industrial areas. Specifically, in the tourism gentrification of historical, cultural, and rural areas, residents have direct and close connections with visitors. Hence, the social isolation caused by tourism is less obvious. However, the living areas of traditional industrial areas are mostly separated from factories. Once the conventional production function of the industrial regions is transformed into leisure and entertainment functions, the identity of residents’ changes. Residents are no longer the stakeholders of the spaces but become the bystanders of this area, resulting in a more pronounced sense of social isolation.

Additionally, conflicts can arise between the functions of spaces for tourism and residence in traditional industrial areas. These conflicts may manifest as the privatization of public space within industrial areas, such as reduced space for non-commercial activities, overcrowding in public spaces, and the loss of essential gathering places [

32]. There may also be a touristification of public services, including changes in local supply systems, traffic congestion, and the emergence of new venues [

7]. These changes can also lead to a loss of social bonds within the community, polarization, and the fragmentation of regional culture [

45]. Lastly, the commodification of regional consumption, marked by shifts in consumption patterns and the emergence of new business models, can further strain the community [

41]. In traditional industrial areas, community spaces are not solely residential but also serve leisure and tourism purposes. The transformation of these areas to cater to tourism can reshape the physical landscape and alter the community's demographics to align with tourism development. However, for most residents, the benefits of tourism development remain elusive, leading to negative impacts on the societal, economic, cultural, and environmental aspects of both industrial and surrounding areas.

2.2. Impacts of Tourism Gentrification

The negative impacts of tourism gentrification have been studied by many scholars, including class differentiation, urban destruction, loss of livelihood of residents, social isolation, employment, and poverty [1, 21, 51]. Among these,

displacement is the most debated issue, manifested as the original residents leaving their apartments or residences due to tourism development [

38]. As the middle class continues to move into these areas, it results in a substantial transformation of the region's social and economic structure [

42]. The process of gentrification can lead to the phenomenon of displacement, including direct (i.e., physical and economic displacement) and indirect displacement (i.e., potential and exclusive displacement) [

33]. Specifically, physical displacement is due to changes in the housing structure in the living environment, resulting in forced evictions. For example, residents may move out due to water and power cuts. Economic displacement is the most common form of gentrification, referring to households being compelled to move due to surging property prices and rents. The sharp reduction in affordable housing options for original residents often leads to their displacement from gentrifying communities. On the other hand, indirect displacement encompasses exclusive and potential displacement, having more psychological stressors. Exclusive displacement means the gentrification process makes it difficult for the original residents to return under the same economic conditions. In gentrified residential areas, the choices of residential houses for the original residents are limited, resulting in the original residents moving out of the block and never returning. Potential displacement refers to the enormous changes in the community caused by gentrification, which will lead to cultural changes, population migration, business changes, etc. The original residents have psychological stress and lose the sense of belonging to the community, which causes residence relocation [

51]. Thus, tourism gentrification affects the local economy and residents’ well-being and results in a severe issue of displacement.

In addition, tourism gentrification leads to a severe issue of

social polarization [

21]. Given the labor-intensive characteristics of tourism, gentrification is more implicit in low-income communities. This kind of invisible social polarization manifests as the transformation of touristification of consumption and production [

38], which may not be beneficial for the community. In particular, original residential properties are transformed according to the needs of tourists, which causes the original residents to feel a sense of alienation and exclusion. The loss of industrial spiritual places and gathering places of the indigenous people can result in a reduction in income and invisible life pressure [

4]. Thus, tourism gentrification accelerates the capital accumulation for wealthy groups and leads to a contradiction between classes. Real estate developers then use the class contradiction to enhance land values, investment, and redevelopment. Tourism gentrification indirectly improves the environment and infrastructure around communities, increases the price of surrounding land, and aggravates social differentiation and population flow [

19]. However, it alienates the indigenous people who have lived there for generations.

2.3. Stress Threshold Theory

The stress threshold theory posits that relocation is a behavior caused by residents' dissatisfaction and anxiety about the current living environment, and it is a process of an individual or family adapting to the living environment [

50]. Thus, tourism gentrification can be viewed as a reflection of the pressure arising from the material and social aspects of residents' living environment, with displacement being the ultimate outcome. This displacement encompasses both direct and indirect forms, including residents being compelled to leave their communities or voluntarily choosing to relocate due to the pressures emanating from their material and social surroundings. Building upon the foundational concepts of tourism gentrification and considering the unique attributes of traditional industrial regions, in this study, we define tourism gentrification as a process driven by the reconfiguration of spatial functions and the transformation of service provisions, resulting in displacement. Within this context, the original residents, especially the retired factory workers, have gradually been marginalized and feel severe psychological stress from their lost rights as hosts. Despite tourism development's overarching goal of maximizing benefits for all stakeholders, it is essential to recognize and address the conflicts, including heightened social differentiation, the erosion of cultural ambiance, and disparities in public service provision. Therefore, this study focuses on residents’ perceptions toward tourism gentrification in traditional industrial areas by investigating residents’ stress formation that shapes relocation decisions.

3. Method

3.1. Research Site

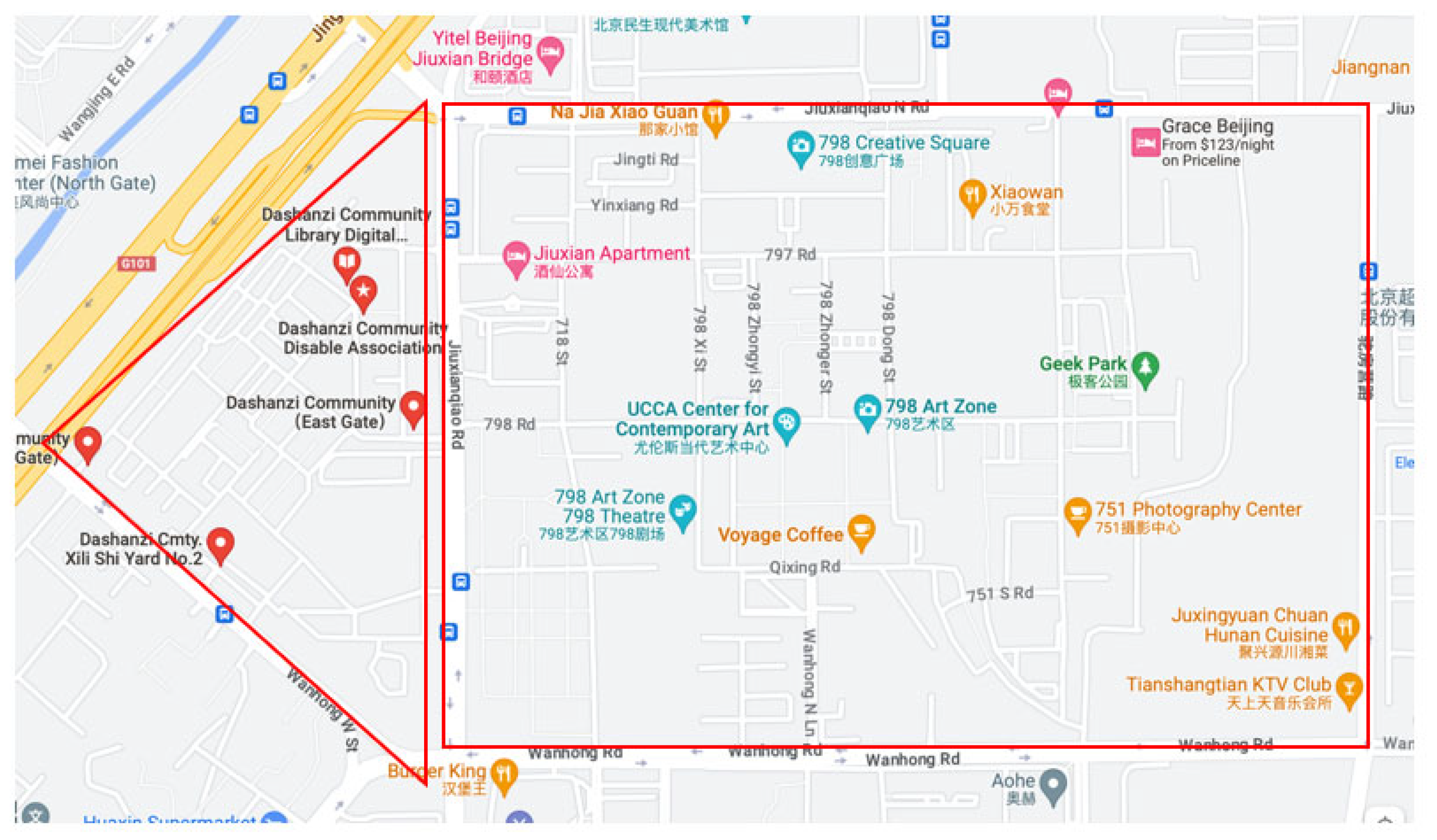

798 Art Zone is located in Beijing, China. It was initially the state-owned 718 Joint Factor, then formed spontaneously by the market and was established by the state as a national cultural and creative art zone [

35]. Since the first batch of artists settled in 1995, a large number of artists moved in and established studios and workshops, including design exhibitions, art performances, and commercials (e.g., bar and handcraft stores). Thus, the 798 Art Zone became an essential and innovative attraction for visitors. The original people belonging to the 718 Joint Factor live next to the 798 Art Zone and have formed the community for more than 60 years, named the “Dashanzi community” (shown in

Figure 1). The issues in the community (e.g., sanitation, traffic congestion, noise, and complex population) have seriously affected the daily life of community residents [

36]. In the past 20 years, the phenomenon of gentrification has become evident in the community. As more tenants moved in, constant reconstruction expanded the commercial areas. However, many former industrial area residents, now retired, have limited involvement in or have never visited the 798 Art Zone, leading to a gradual weakening of their ties to the original industrial areas.

3.2. Procedures

This study employed Q methodology to uncover the residents’ subjective perceptions regarding the impact of tourism development of the 798 Art Zone in order to understand their stress related to tourism gentrification. Q methodology is a psychological research method that focuses on personal feelings, attitudes, and opinions [

2]. It is a scientific approach to studying human subjectivity, as it requires respondents to express their subjective feelings and ideas clearly and profoundly while emphasizing the collection of individual opinions [

40]. In essence, Q methodology tests a limited number of people using a set of items. It aims to quantitatively measure subjectivity by combining qualitative approaches with data manipulation techniques commonly found in quantitative research. This approach has the representativeness and feasibility of large-scale statistical analysis and harnesses the analytical strengths of both qualitative and quantitative research [

28]. Data collection and analysis followed the steps of the Q methodology outlined in the previous tourism studies [

43].

In the first step, the goal was to gather Q statements through semi-structured interviews. The interviews were conducted from April 9

th to 18

th, 2021, involving ten participants who were formerly factory workers and now live in the Dashanzi community. They were asked about their feelings and opinions regarding landscape, transportation, public facilities, neighborhood, and tourism's impact on the community. For example, “What changes are there in the community since the development of the 798 Art Zone?”, “How has tourism development of the 798 Art Zone influenced your life?” and “Have you considered relocating? If so, why or why not?”. The interviews were stopped when the results achieved the principle of saturation [

6]. A total of 56 statements related to tourism gentrification were created (see

Appendix A).

The second step involved selecting a Q sample through expert consultation and debriefing. Q sample refers to the representative statements chosen by the researchers from the initial Q statements [

43]. In order to increase the validity and reliability and reduce researcher bias factors, experts were consulted to enhance the clarity and accuracy of the expressions. Similar expressions were removed, resulting in the retention of 33 different statements. Previous participants were invited to discuss these statements and remove any controversial expressions that did not align with the actual situation. As a result, the finalized Q sample consisted of 26 statements (shown in

Table 1).

The subsequent step was P sample selection. Participants needed to be familiar with the topics and willing to participate in the research. Thus, 20 current residents (See demographics in

Table 2) from the Dashanzi community were invited. They were chosen because they could provide diverse perspectives on historical changes, emotional attachment, and contemporary social impacts in the industrial areas, aligning with the requirements of Q methodology for various sample characteristics.

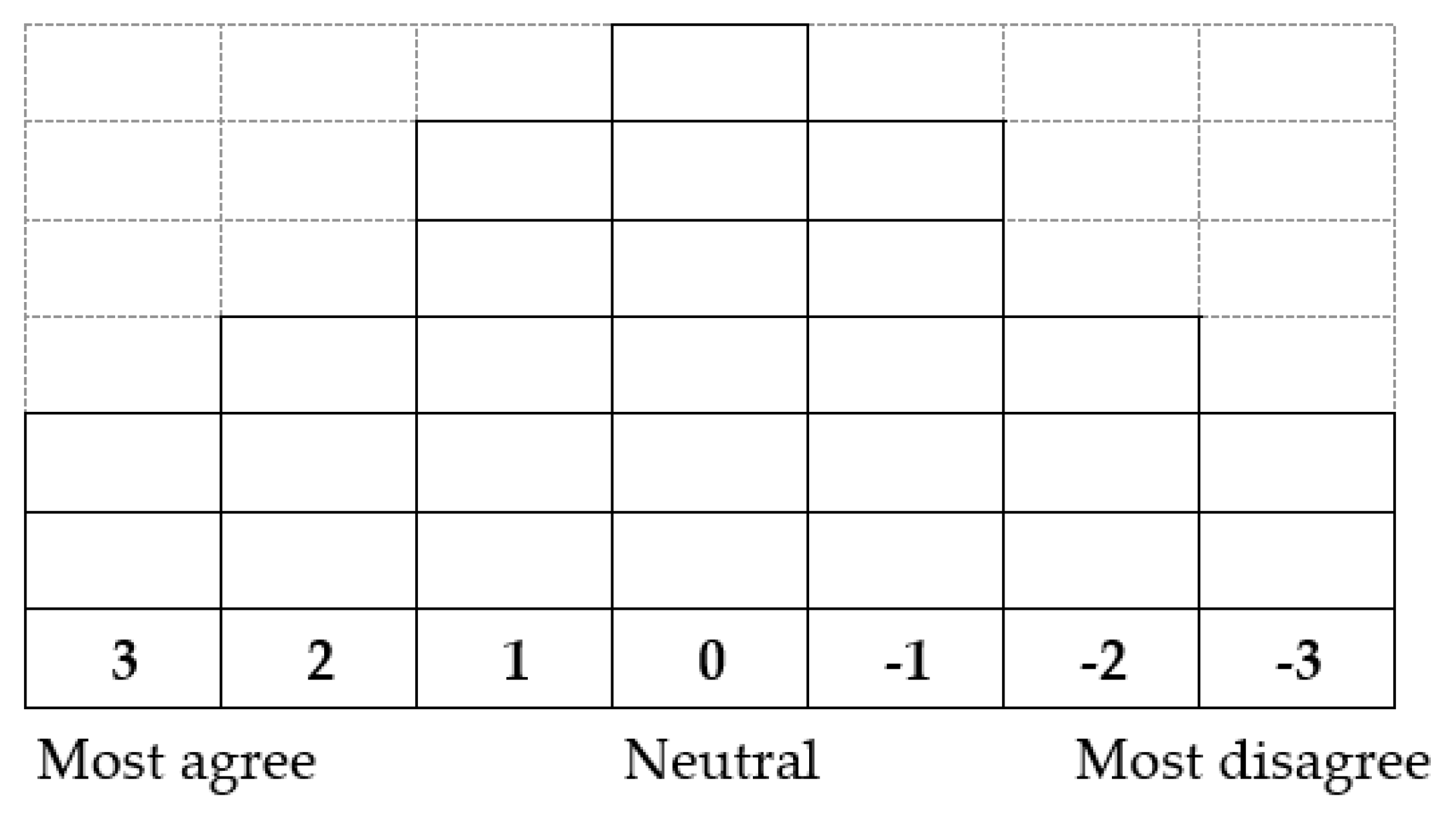

The last step was Q sorting, which was performed from May 3

rd through May 10

th, 2021. The researchers made 26 statement cards (classification cards), and the participants were asked to rank these cards in the Q sorting table. On the basis of their understanding of each statement, the participants first divided cards into three groups: ‘Most agree,’ ‘Neutral,’ and ‘Most disagree.’ Then, they assigned a score to each card according to a normal distribution diagram from -3 to 3 (See

Figure 2). Participants selected the two most favorable cards of statements from the ‘most agree’ group and placed them in the 3-point category. Then, three cards were allocated to the 2-point category, and five cards were allocated to the 1-point tables based on the degree of agreement. Similarly, the participants sorted the statements into the ‘most disagree’ group using the same criteria and placed them in the normal distribution scoring table. The remaining six cards formed the neutral group. Finally, the researchers conducted one-on-one interviews with all participants to gain insights into their thoughts and perceptions regarding each statement.

4. Results

The analysis process was performed using PQMethod (version 2.11), which calculated the correlation matrix among the Q sorting responses and indicated the degree of agreement or disagreement. The results provided a comprehensive sorting of statements and statistical validity for each factor. After the steps of factor rotation and scoring, the results were grouped into sets of statements and formed the basis for determining the dimensions of residents' stress related to tourism gentrification in traditional industrial areas. The analysis revealed four dimensions, resulting in a cumulative interpretation rate of 65.84%. With orthogonal rotation, the four factors were used to determine the factor load of each sample, where a factor load > 1/ √n *(2.58) was considered (n represents the number of Q samples) [

18]. In this study, with n equal to 26, the factor load needed to be above 0.505, which met the criteria. Through factor interpretation, the four dimensions represented residents’ perceptions of tourism gentrification in traditional industrial areas, namely, neighboring environment (31.936%), community attachment (27.425%), economic interest (21.744%), and cultural identity (18.895%).

Factor 1: Neighboring Environment

Six participants are closely related to this factor (i.e., P2, P7, P8, P12, P13, P15). The distinguishing statements with the Z score are shown in

Table 3. The challenges of tourism development and public space privatization are increasing. Residents who originally worked and lived in industrial areas are gradually excluded, leading to the loss of their former leisure gathering places and a negative impact on the living environment. Community health is deteriorating, so noise pollution and parking congestion profoundly affect residents. Interviewee 8, a retired employee of the former 718 factory, mentioned, “

To be honest, the 798 Art Zone is a place where young people like to go. The older people cannot understand the art exhibition, and there is nothing for us to engage with. This place no longer feels like it belongs to us.” Most respondents shared negative attitudes toward the changes in the industrial areas and community environment, believing it has become less suitable for their residence. They believed that their quiet lives had been disturbed, reducing happiness. For instance, one respondent stated,

“I am often asked for directions, and I am tired of it.” (P13). Another mentioned, “

There are tricycles transporting tourists from the subway to central 798 Art Zone. They speed through the community very fast, which is a problem if they encounter elderly people in the community. Another is that the barbecue stores along the street are very noisy at night, so I cannot sleep at all. Some tenants in the corridor come back in the middle of the night and speak loudly in the hallway.” (P15) Another concern was raised, “

New people working in the 798 Art Zone will park in the community, so we do not have spaces to park and live.” (P2) Despite most respondents having a negative perception of the tourism development in the industrial area, some believed that basic service facilities had been improved with regional improvement.

Factor 3: Economic Interest

Four interviewees are attributed to this factor (i.e., P1, P4, P5, P11). The distinguishing statements with the Z score are demonstrated in

Table 5. The majority of respondents indicate that their families and local communities do not directly benefit economically from the 798 Art Zone. Instead, they face economic pressure from the high cost of living and increasing product prices. As argued by interviewee 1, “

After the transformation of the industrial zone into a famous art zone, it has become easy to rent apartments in our community. Thus, many residents rent out their apartments and leave the community. These apartments are old and small, but the rent is not cheap.” Most respondents agreed that tourism in the 798 Art Zone had led to an increase in local product prices and living costs. However, interviewee 11 presented a different perspective, “

The transformation of the industrial area into an art zone has provided valuable opportunities for learning and entertainment. It is better than tearing down the industrial area. Many fashion stars have visited the 798 Art Zone and taken photos at a gorgeous art wall. Sometimes, it is good to go and refresh myself with new experiences.”

Factor 4: Cultural Identity

Five interviewees belong to this factor (i.e., P3, P10, P17, P18, P20). The distinguishing statements with the Z score are shown in

Table 6. The interviewees generally agree that tourism development elevates the reputation of the 798 Art Zone but also erodes the essential spirit and culture, making the environment in this region unfamiliar and causing a loss of the sense of belonging. As stated by respondent 10, “

I rarely go to the industrial zone side because it evokes an uncomfortable and strange feeling. I remember when the factory was prosperous, but now it feels decayed. The distinctive cultural atmosphere we once had has vanished. In fact, this factory used to be a source of great pride.” Another respondent, 18, expressed, “

When the 798 Art Zone was developed initially, some friends invited me to take a tour. However, I no longer go there because commercialization has become too common, and there is a lack of appreciation for the arts.” Some respondents believed that the spirit and culture of this industrial zone had disappeared. Nevertheless, there were interviewees who maintained a positive attitude. As respondent 3 argued, “

The industrial zone represents the memory of the past. The tree at the entrance of the gate was small when I started working there. Now, it has grown large, and seeing it brings back a lot of memories. We should accept the transformations in this industrial zone.” For many retired factory workers, the industrial area holding memories of the past is fading as the area undergoes changes.

5. Discussion

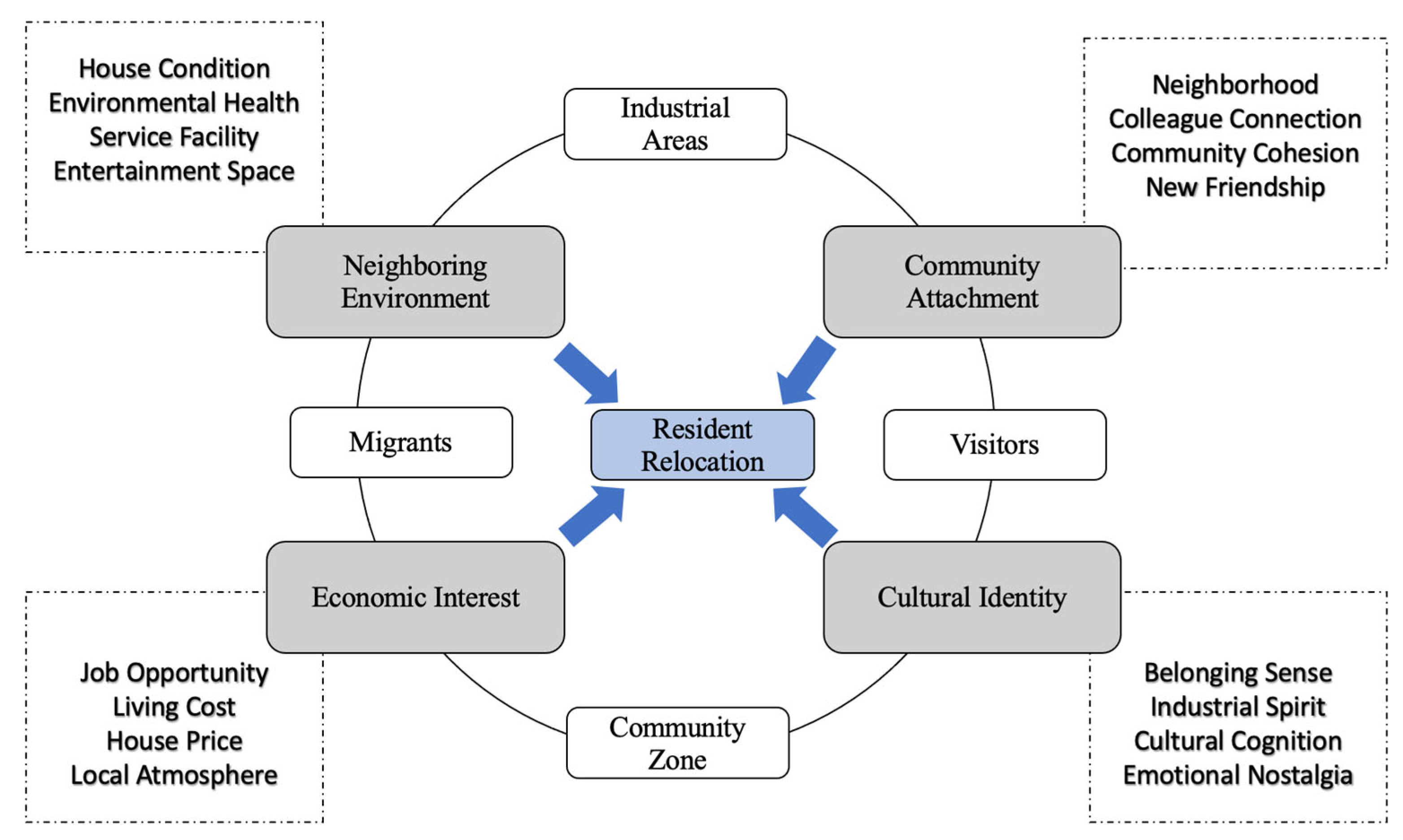

The process of tourism gentrification causes stress on the original residents and is multidimensional and profound. Drawing from the case of 798 Art Zone and analysis via Q methodology, the results can be generalized to suggest that residents’ stress stemming from tourism gentrification in traditional industrial areas can be categorized into four dimensions: environmental, relational, economic, and emotional.

Neighboring environment refers to the immediate surroundings of those in close proximity to a specific area or community. It encompasses the physical, ecological, and social elements that influence and interact with the focal point, including buildings, transportation, shops, parks, air quality, noise level, garbage management, etc. Industrial buildings with distinct characteristics can carry spiritual comfort and satisfaction to residents who have worked and lived in the areas for their entire lives. Reconstruction of industrial regions often involves changes in house conditions and architectural styles, incorporating creative, fashionable, and diversified elements. This reorganization of the spatial structure leads to the improvement of service facilities and the emergence of new businesses catering to visitors, such as clubs, bars, and art galleries. Local restaurants are often replaced by chain stores and brand restaurants, causing residents to gradually lose their entertainment venues and communal spaces and shifting local consumption patterns. These changes have adverse effects on the natural and material environment. Numerous scholars have explored the impact of environmental damage on residents' relocation decisions [

25]. Therefore, in line with previous studies, the environmental dimension is vital in influencing residents’ migration decisions.

Community attachment can be described as the emotional and psychological connections that individuals or communities feel toward their local neighborhood or residential area. It signifies a sense of belonging, identity, and investment in the place where one lives. These connections in industrial areas encompass community relationships, collective bonds, social participation following transformation, place attachment, and emotional support. Acquaintances in industrial areas often mutually help earn benefits, provide emotional support, and exchange valuable information. However, by changing these areas into tourist destinations, interpersonal connections become superficial and formalized. Residents become more individualized and find it challenging to establish new friendships and community cohesion. Thus, community attachment disappears, creating an atmosphere of alienation and distrust. This, in turn, reduces residents' happiness and accelerates the gentrification process. The importance of factors (e.g., leisure spaces, service facilities, local norms, community reputation, and safety) should be emphasized from the perspective of resource allocation and collective function. Therefore, this study underscores the significance of considering the relational dimension in residents' decisions to relocate.

Economic interest concerns personal financial involvement in a situation, project, investment, or outcome. It signifies motivation by the potential for financial gain, benefit, or impact. As an essential interest group in industrial areas, residents’ attitudes and support are of great significance to the sustainable development of industrial tourism. However, in the process of tourism transformation, original factory workers often fail to participate in the economic growth or gain financial benefits. They become marginalized and gradually ignored. Residents’ economic benefits have received attention from scholars, such as job creation and business opportunities during the process of gentrification [

9]. However, the stress related to rising house and product prices, living costs, and competitive employment opportunities should be highlighted. Particularly, the local atmosphere has shifted from the previous harmonious relationships to the current profit-oriented ambiance. As a result, the economic dimension plays an important role in residents’ movements.

Cultural identity describes the sense of belonging, connection, and identification that individuals or groups feel with a particular culture. It encompasses the shared values, beliefs, customs, traditions, language, and social practices that shape a person's self-concept within the industrial areas of their cultural heritage. Traditional industrial regions have witnessed the unique development of modern industrialization. These areas are not only where people once lived and worked but also repositories of emotional memories and spiritual havens. During the tourism transformation process in traditional industrial areas, the social environment and cultural cognition undergo reshaping, significantly impacting local culture and residents’ identity. The carriers symbolic of industrial spirit and emotional nostalgia are damaged, negatively impacting the original culture. Residents with a strong sense of local identity are excluded from tourism development, leading to a reduced sense of belonging to the community. Consequently, the cultural dimension is critical in driving residents’ intention to relocate.

Residents’ stress arising from the interactions with migrant workers and visitors in both industrial regions and communities is defined through the above four dimensions. Traditional industrial areas possess unique regional attributes, and the original residents closely connect to the industrial sites. Within the overlapping spaces of industrial regions and communities and influenced by the social environment shaped by both visitors and migrant workers, we propose a framework illustrating the impact of tourism gentrification on residents’ relocation decisions in traditional industrial areas (see

Figure 3).

We argue that tourism gentrification is a process in which the primary beneficiaries of industrial areas gradually shift from residents to visitors. This shift puts pressure on original residents to relocate. It encompasses both material survival and psychological pressure. This stress is formed through changes not only in the physical environment and social relations but also in economic benefits and local culture. When residents experience the adverse effects of tourism development, they often face invisible pressures that push them toward moving away from the community. Those who choose to stay in the face of tourism gentrification are likely to endure stress from their communities, local businesses, public facilities, and modern services. This, in turn, results in areas becoming increasingly uninhabitable for original residents. Consequently, tourism gentrification significantly influences residents’ decisions to relocate.

6. Implications and Future Studies

6.1. Theoretical Implications

This study significantly contributes to the literature on tourism gentrification. It is the first to conceptualize tourism gentrification in traditional industrial areas by elucidating the excessive stress that drives residents’ relocation decisions. Tourism gentrification is essentially a displacement resulting from the reconstruction of spatial functions and the transformation of service targets in industrial areas. In this process, conflicts between indigenous residents and visitors manifest in various forms, such as the privatization of public space, the commodification of consumer facilities, the touristification of public services, the loss of social bonds in communities, the commodification of regional consumption, and the rejection of a tourist-dominant social culture. These factors collectively contribute to increased stress among residents, motivating them to consider relocating. The gentrification of businesses driven by tourism gradually reduces residents' reliance on local shops for daily needs, leading residents to withdraw from their original spatial domains. This shift raises residents’ stress and changes their roles as service providers in the broader sense. Consequently, this study enhances our comprehensive understanding of tourism gentrification in traditional industrial areas from the perspective of residents.

Furthermore, the study proposes a conceptual framework for understanding residents’ perceptions of tourism gentrification in traditional industrial areas. Employing the Q methodology, the study highlights the origin of residents’ stress in four dimensions: neighboring environment, community attachment, economic interest, and cultural identity. These pressures often arise from interactions with migrants and visitors. Traditional industrial areas possess unique features, serving as repositories of residents’ emotional memories, living and working spaces, and social settings. Hence, residents’ stress can also stem from changes in the functions of the industrial areas, shifting from the previous workplaces to current tourism destinations. The relationship between workplaces and the community has gradually become isolated, serving as a catalyst for relocation decisions in the context of tourism gentrification. Therefore, this framework elucidates the intricate phenomenon of relocation in traditional industrial areas, which enriches the literature on tourism gentrification and fills the gap regarding the revival of industrial tourism.

6.2. Managerial Implications

Understanding the stress experienced by residents from tourism gentrification in traditional industrial areas can provide practical guidance to policymakers and destination managers seeking to mitigate negative impacts and promote social justice and harmony. Tourism development in such areas should aim to address the challenges posed by the high degree of overlap between local daily life and the tourism experience. In the formulation of tourism policies and regulations, it is imperative to recognize the viewpoints and attitudes of community residents toward tourism development. Local residents have strong affection and loyalty to their areas, entitling them to participate in the entire process of tourism development and implementation, given that these decisions directly affect their quality of life. For these reasons, the objectives should be the fair distribution of spaces and resources to minimize the potential negative consequences of tourism gentrification. The process of tourism transformation should align with the diverse demands of all stakeholders in traditional industrial areas.

More importantly, it is acknowledged that tourism gentrification may negatively impact the local residents. Increased housing prices often lead to displacement of indigenous populations and exacerbate social class differentiation and spatial isolation. Residents should play a vital role in tourism activities and reap the benefits of tourism achievements. Therefore, policymakers should realize that it is necessary to establish and enhance the relevant social security system, provide employment guidance, and diversify tourism activities to assist residents in being more involved in the transformation. For example, monthly regular seminars can invite residents, operators, and staff to explore ways to promote and collaborate among local businesses. Increasing residents' participation rates and reinforcing the construction and maintenance of the living environment can benefit all stakeholders and enhance place recognition in traditional industrial areas.

Ultimately, local cultural and industrial heritage are invaluable resources for tourism development. In the reconstruction and revival of traditional industrial areas, it is recommended that policymakers formulate regulations to protect heritage, such as historical buildings and activities of intangible culture. Destination managers must consciously preserve the local culture, industrial heritage, and ecological system. For instance, traditional industrial areas can allocate spaces for small industrial museums or exhibitions that showcase their illustrious history and cultural stories, honoring workers and commemorating significant events. These types of initiatives can provide opportunities for retired workers to find re-employment and enhance residents' sense of belonging and pride. Nurturing residents' sense of local pride and cultural consciousness, effectively influencing visitors and migrants, will attract more visitors and promote the sustainable development of industrial tourism.

6.3. Limitations and Future Studies

This research primarily focuses on the case of the 798 Art Zone, which represents the traditional industrial areas undergoing tourism development. This particular case embraces tourism development through a creative approach involving art and fashion with unique characteristics. However, it's essential to recognize that other traditional industrial areas may pursue tourism development in different ways, such as industrial recreational playgrounds or historical theme parks. Moreover, it's essential to acknowledge that tourism gentrification is a long-term and dynamic process, with each stage presenting unique characteristics and issues related to tourism development. To gain a comprehensive understanding, future research should delve into the distinct phases of gentrification via different means of tourism development, considering the perspectives of various stakeholders.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.L.; methodology, Q.W.; validation, B.L.; formal analysis, B.L. and Q.W.; investigation, Q.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.W. and B.L.; writing—review and editing, W.L.; visualization, B.L.; supervision, W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is sponsored by the Ministry of Education of China, Humanities and Social Sciences Research Project (No. 21YJA790052). This research is sponsored by the State Key Laboratory of Coal Resources and Safe Mining (No. SKLCRSM20KFA10). This research is sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42271255).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Q Statements

Neighborhoods are being replaced by visitors.

The primary spatial functions have undergone changes.

Many residents have moved out.

My children and relatives have moved from this community.

Tourism development has not increased my income.

The relationships with neighbors have changed.

House prices have risen significantly in residential areas.

Residents cannot get profits from the development of the 798 Art Zone.

Many tenants are moving into the community.

The place where I used to work is becoming more and more strange.

The living condition of the community is getting worse.

The well-being of residents has been influenced.

Competition for job opportunities is becoming increasingly fierce.

The living cost has increased significantly.

The surrounding living environment has been affected.

It is difficult for my relatives and me to find a job in the 798 Art Zone.

I retire and stay here because of familiarity.

The inhabitancy sanitation condition has gotten worse.

The development of tourism resources has triggered an increase in local prices.

I do not feel safe due to the complex community.

It is so noisy at night.

Transportation is getting worse.

Housing and infrastructure are old and run-down.

Service facilities in the community are relatively old.

Visitors always come to the community.

I cannot understand the shows and exhibitions in the 798 Art Zone.

The landscape of old industrial areas has been reshaped.

Creativity has become the core of the 798 Art Zone.

It is difficult for me to adapt to this fashionable atmosphere of the 798 Art Zone.

Economic reconstruction leads to social-spatial reconstruction.

The urban physical environment has been damaged.

Commercial activities affect the community significantly.

The natural environment has been negatively influenced.

The prices of surrounding real estate have increased.

Living conditions are inconvenient.

The community has turned into a space for visitors.

Many familiar friends and colleagues have moved away.

The neighborhood is not as close and harmonious as before.

It is hard to make friends because of the high population turnover.

Pressure has increased in daily life.

Residents’ lives are often disturbed by tourists.

Housing is being converted into short-term rentals or hotels.

The number of bars and restaurants has increased.

Overcrowding is causing mobility problems in the community.

There are no certain places for residents to hang out and find entertainment in the 798 Art Zone.

People work nearby and visitors always park in the community.

Tourists seldom communicate with us except by asking for directions.

The awareness of fashion has enhanced.

The original appearance and functions of the industry have been changed in the 798 Art Zone.

The pride that this place once brought to me has disappeared.

The 798 Art Zone is famous worldwide.

A fashionable atmosphere has been created in the community.

The places I used to work bring back a lot of memories.

The sense of belonging is gradually lost.

Loss of social connections is noticeable.

People think of relocation.

References

- Almeida-García, F.; Cortés-Macías, R.; Parzych, K. Tourism Impacts, Tourism-Phobia and Gentrification in Historic Centers: The Cases of Málaga (Spain) and Gdansk (Poland). Sustainability 2021, 13, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ásványi, K.; Miskolczi, M.; Jászberényi, M.; Kenesei, Z.; Kökény, L. The Emergence of Unconventional Tourism Services Based on Autonomous Vehicles (AVs)—Attitude Analysis of Tourism Experts Using the Q Methodology. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancur, J.J. Gentrification in Latin America: Overview and Critical Analysis. Urban Stud. Res. 2014, 2014, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, J.; Lees, L. Gentrification in New York, London and Paris: An International Comparison. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 1995, 19, 286–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y. Beyond displacement: the co-existence of newcomers and local residents in the process of rural tourism gentrification in China. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W.; Creswell, J. D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, USA, 2018.

- Dimitrovski, D.; Crespi-Vallbona, M.; Ioannides, D. How do locals perceive the touristification of their food market? The case of Barcelona's La Boqueria. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 24, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevens, A.; Cocola-Gant, A.; López-Gay, A.; Pavel, F. The role of the state in the touristification of Lisbon. Cities 2023, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, F. A.; Vázquez, A. B.; Macías, R. C. Resident's attitudes towards the impacts of tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 13, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, R. Centre for Urban Studies. Town Plan. Rev. 1963, 34, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Pérez, J.M. The dispute over tourist cities. Tourism gentrification in the historic Centre of Palma (Majorca, Spain). Tour. Geogr. 2019, 22, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotham, K.F. Tourism Gentrification: The Case of New Orleans' Vieux Carre (French Quarter). Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 1099–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassink, R.; Hu, X.; Shin, D.-H.; Yamamura, S.; Gong, H. The restructuring of old industrial areas in East Asia. Area Dev. Policy 2017, 3, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Giralt, C.; Palacios-García, A.; Barrado-Timón, D.; Rodríguez-Esteban, J.A. Urban Industrial Tourism: Cultural Sustainability as a Tool for Confronting Overtourism—Cases of Madrid, Brussels, and Copenhagen. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospers, G.-J. Industrial Heritage Tourism and Regional Restructuring in the European Union. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2002, 10, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Hassink, R. New perspectives on restructuring of old industrial areas in China: A critical review and research agenda. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2015, 27, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Qu, H.; Montgomery, D. The Meanings of Destination: A Q Method Approach. J. Travel Res. 2016, 56, 793–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutson, G.; Montgomery, D. Stakeholder views of place meanings along the Niagara Escarpment: an exploratory Q methodological inquiry. Leis. 2010, 34, 421–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannides, D.; Röslmaier, M.; Van Der Zee, E. Airbnb as an instigator of ‘tourism bubble’ expansion in Utrecht's Lombok neighborhood. Tour. Geogr. 2019, 21, 822–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jover, J.; Díaz-Parra, I. Gentrification, transnational gentrification and touristification in Seville, Spain. Urban Stud. 2019, 57, 3044–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, H.; Takizawa, A. Population Decline through Tourism Gentrification Caused by Accommodation in Kyoto City. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Holifield, R. Touristification, commercial gentrification, and experiences of displacement in a disadvantaged neighborhood in Busan, South Korea. J. Urban Aff. 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzior, A.; Lyulyov, O.; Pimonenko, T.; Kwilinski, A.; Krawczyk, D. Post-Industrial Tourism as a Driver of Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Park, C. Mitigating the impact of touristification on the psychological carrying capacity of residents. Sustain. 2021, 13, 2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, G.; Graefe, A.; Manning, R.; Bacon, J. An Examination of the Relationship between Leisure Activity Involvement and Place Attachment among Hikers Along the Appalachian Trail. J. Leis. Res. 2003, 35, 249–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-F. An investigation of factors determining industrial tourism attractiveness. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2015, 16, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-H. Conflict mapping toward ecotourism facility foundation using spatial Q methodology. Tour. Manag. 2018, 72, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, L. Super-gentrification: The case of Brooklyn Heights, New York City. Urban Stud. 2003, 40, 2487–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.-X.; Bao, J.-G. Tourism gentrification in Shenzhen, China: causes and socio-spatial consequences. Tour. Geogr. 2015, 17, 461–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhu, X.; Li, J.; Sun, J.; Huang, Q. Progress of Gentrification Research in China: A Bibliometric Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Rao, X.; Duan, P. The Rural Gentrification and Its Impacts in Traditional Villages―A Case Study of Xixinan Village, in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandeli, K. Public space and the challenge of urban transformation in cities of emerging economies: Jeddah case study. Cities 2019, 95, 102409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcuse, P. Gentrification, abandonment, and displacement: Connections, causes, and policy responses in New York City. Wash. UJ Urb. & Contemp. L., 1985, 28, 195. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Hernández, C.; Yubero, C. Explaining Urban Sustainability to Teachers in Training through a Geographical Analysis of Tourism Gentrification in Europe. Sustainability 2019, 12, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.; Wang, Y. Culture, creativity and commerce: trajectories and tensions in the case of Beijing's 798 Art Zone. Int. Plan. Stud. 2016, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, P.B.; Oberg, A.; Nelson, L. Rural gentrification and linked migration in the United States. J. Rural. Stud. 2010, 26, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otgaar, A. Towards a common agenda for the development of industrial tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 4, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, G.-M. Touristification and displacement. The long-standing production of Venice as a tourist attraction. City 2022, 26, 519–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequera, J.; Nofre, J. Shaken, not stirred. New debates on touristification and the limits of gentrification. City 2018, 22, 843–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y. (.; Choi, H.C.; Joppe, M.; Yi, S. What motivates visitors to participate in a gamified trip? A player typology using Q methodology. Tour. Manag. 2020, 78, 104074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.B.; Lees, L.; López-Morales, E. Introduction: Locating gentrification in the Global East. Urban Stud. 2015, 53, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N. Gentrification, the frontier, and the restructuring of urban space. In Gentrification of the City. Routledge: Oxfordshire, England, 2013.

- Tan, S.-K.; Luh, D.-B.; Kung, S.-F. A taxonomy of creative tourists in creative tourism. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, R.; Kato, H.; Matsushita, D. Population Decline and Urban Transformation by Tourism Gentrification in Kyoto City. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurber, A.; Krings, A.; Martinez, L.S.; Ohmer, M. Resisting gentrification: The theoretical and practice contributions of social work. J. Soc. Work. 2019, 21, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outón, S.M.T. Gentrification, touristification and revitalization of the Monumental Zone of Pontevedra, Spain. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2019, 6, 347–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, T. (. Developing and Validating a Scale of Tourism Gentrification in Rural Areas. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2021, 46, 1162–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Fu, D.; Diao, Y.; Wang, B.; Gao, X.; Jiang, M. Exploring the Relationship between Touristification and Commercial Gentrification from the Perspective of Tourist Flow Networks: A Case Study of Yuzhong District, Chongqing. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijngaarden, V. Q method and ethnography in tourism research: enhancing insights, comparability and reflexivity. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 20, 869–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpert, J. Migration as an Adjustment to Environmental Stress. J. Soc. Issues 1966, 22, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, J.; Yoon, S. Evaluating the relationship between perceived value regarding tourism gentrification experience, attitude, and responsible tourism intention. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2020, 19, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Gu, C.; Li, D.; Huang, M. Tourism gentrification: Concept, type and mechanism. Tour. Tribune, 2006, 21, 70–74. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ou, Y.; Liu, L. Between Empowerment and Gentrification: A Case Study of Community-Based Tourist Program in Suichang County, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.; Yao, Y.; Li, J. Sociocultural Impacts of Tourism on Residents of World Cultural Heritage Sites in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).