Submitted:

18 September 2023

Posted:

19 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Models

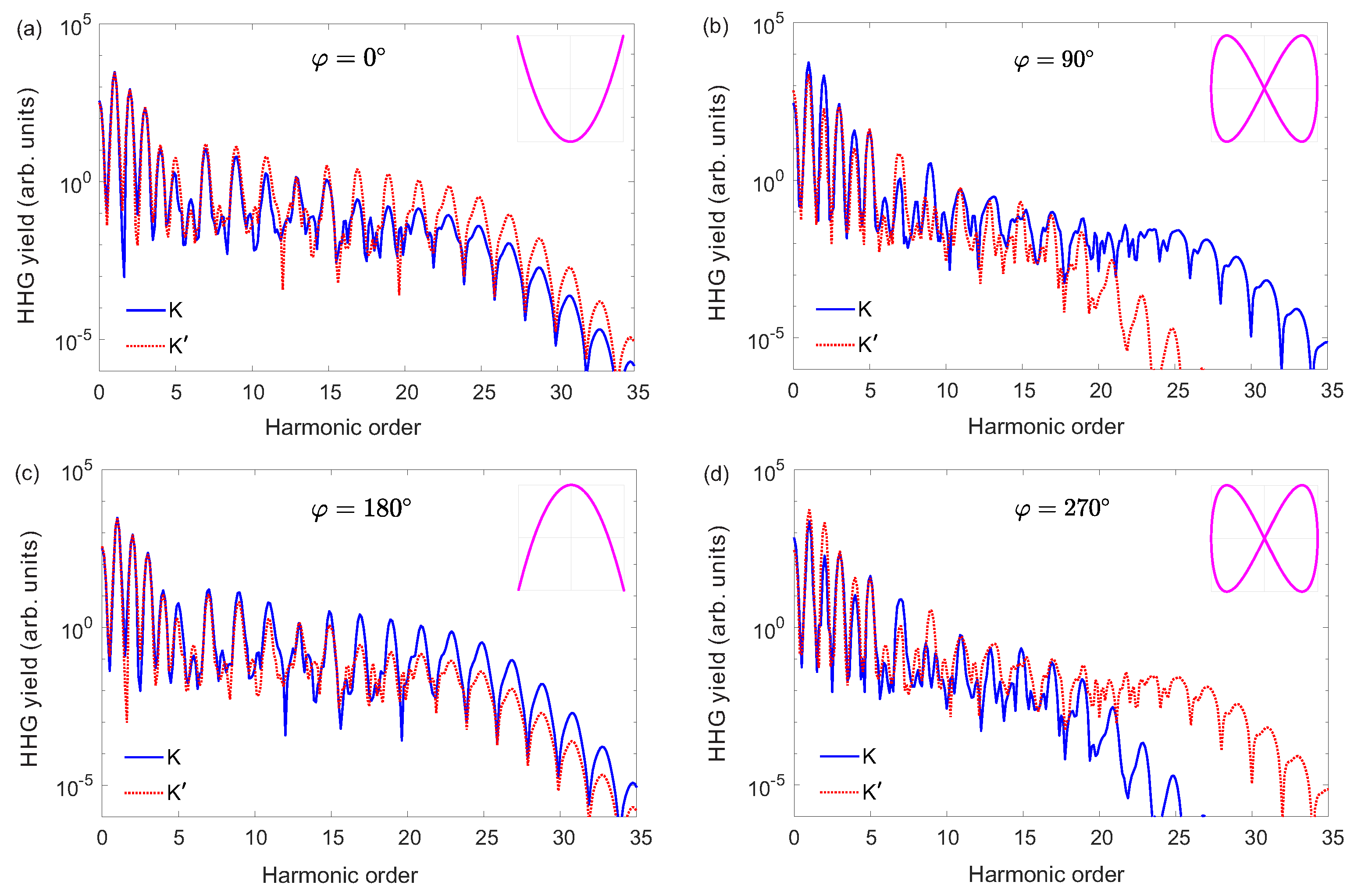

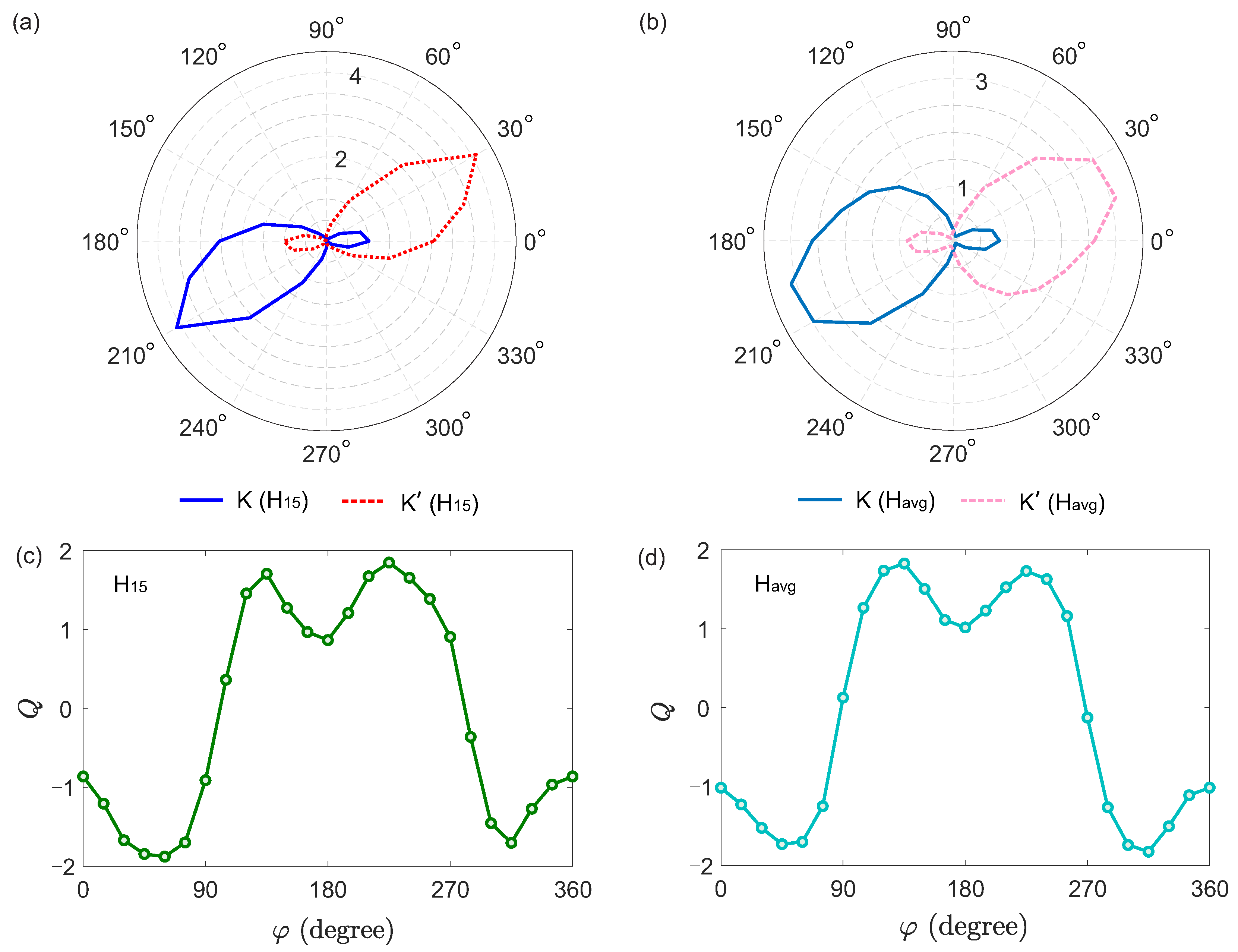

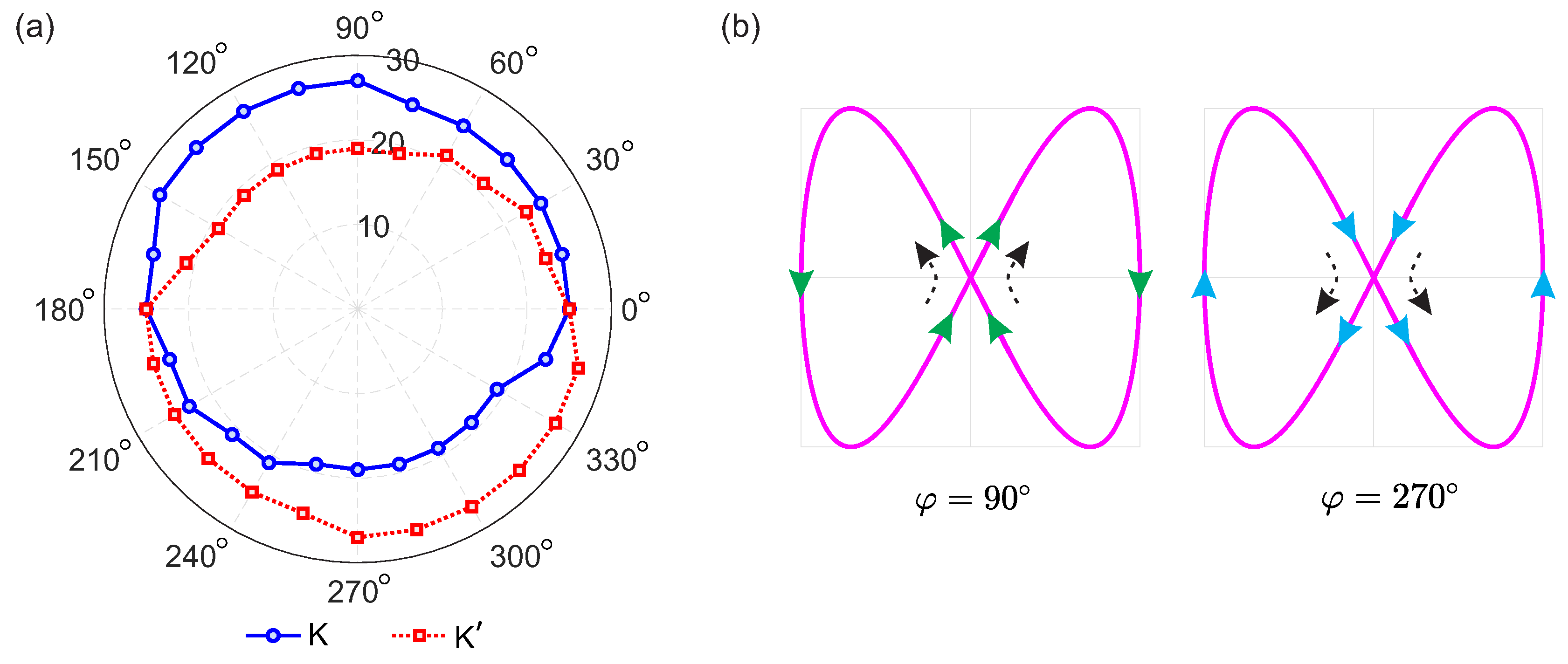

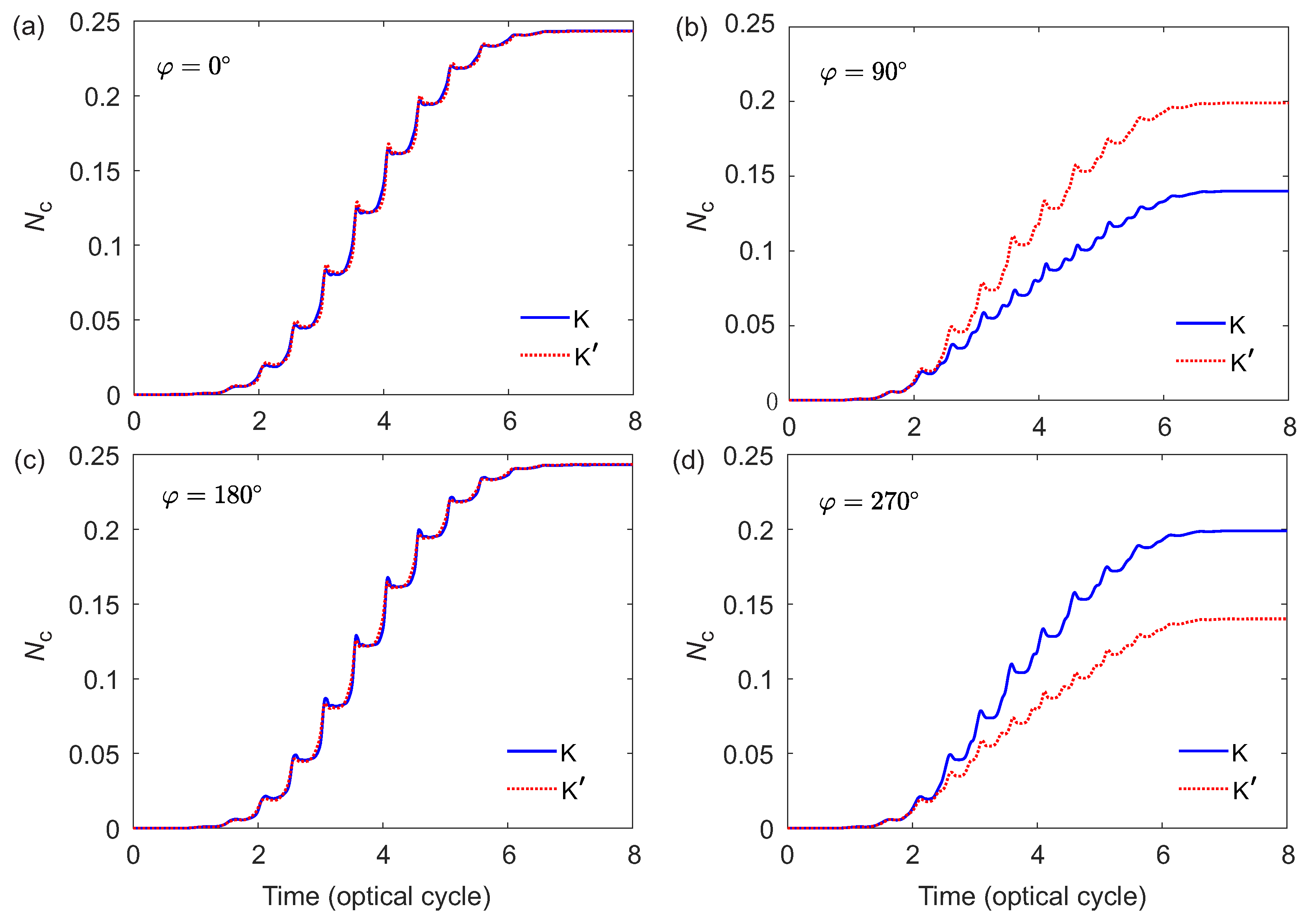

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krausz, F.; Ivanov, M. Attosecond physics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2009, 81, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corkum, P.B.; Krausz, F. Attosecond science. Nat. Phys. 2007, 3, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hentschel, M.; Kienberger, R.; Spielmann, C.; Reider, G.A.; Milosevic, N.; Brabec, T.; Corkum, P.; Heinzmann, U.; Drescher, M.; Krausz, F. Attosecond metrology. Nature 2001, 414, 509–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Lu, P.; Lein, M. Control of the Geometric Phase and Nonequivalence between Geometric–Phase Definitions in the Adiabatic Limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2022, 128, 030401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schafer, K.J.; Yang, B.; DiMauro, L.F.; Kulander, K.C. Above threshold ionization beyond the high harmonic cutoff. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1993, 70, 1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corkum, P.B. Plasma perspective on strong field multiphoton ionization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1993, 71, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewenstein, M.; Balcou, P.; Ivanov, M.Y.; L’Huillier, A.; Corkum, P.B. Theory of high-harmonic generation by low–frequency laser fields. Phys. Rev. A 1994, 49, 2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Lan, P.; Le, A.; Wang, B.; Wang, B.; Zhu, X.; Lu, P.; Lin, C.D. Real–Time Observation of Molecular Spinning with Angular High–Harmonic Spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 121, 163201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganeev, R.A. High–Order Harmonics Generation in Selenium–Containing Plasmas. Photonics 2023, 10, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhu, X.; Li, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Lan, P.; Lu, P. Selection rules of high–order–harmonic generation: Symmetries of molecules and laser fields. Phys. Rev. A 2016, 94, 033410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, P.M.; Toma, E.S.; Breger, P.; Mullot, G.; Augé, F.; Balcou, P.; Muller, H.G.; Agostini, P. Observation of a Train of Attosecond Pulses from High Harmonic Generation. Science 2001, 292, 1689–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatziathanasiou, S.; Kahaly, S.; Skantzakis, E.; Sansone, G.; Lopez-Martens, R.; Haessler, S.; Varju, K.; Tsakiris, G.D.; Charalambidis, D.; Tzallas, P. Generation of Attosecond Light Pulses from Gas and Solid State Media. Photonics 2017, 4, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, C.; Zhu, X.; Long, J.; Shao, R.; Zhang, Y.; He, L.; Tang, Q.; Li, Y.; Lan, P.; Yu, B.; Lu, P. Generation of elliptically polarized attosecond pulses in mixed gases. Phys. Rev. A 2021, 103, 033114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, S.; DiChiara, A.D.; Sistrunk, E.; Agostini, P.; DiMauro, L.F.; Reis, D.A. Observation of high–order harmonic generation in a bulk crystal. Nat. Phys. 2011, 7, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruchinin, S.Y.; Krausz, F.; Yakovlev, V.S. Colloquium: Strong–field phenomena in periodic systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2018, 90, 021002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vampa, G.; Hammond, T.J.; Thiré, N.; Schmidt, B.E.; Légaré, F.; McDonald, C.R.; Brabec, T.; Corkum, P.B. Linking high harmonics from gases and solids. Nature 2015, 522, 462–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, N.; Tamaya, T.; Tanaka, K. High-harmonic generation in graphene enhanced by elliptically polarized light excitation. Science 2017, 356, 736–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S. High–Harmonic Generation Using a Single Dielectric Nanostructure. Photonics 2022, 9, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhu, X.; Lan, P.; Zhang, X.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, P. Time–dependent population imaging for high–order–harmonic generation in solids. Phys. Rev. A 2017, 95, 063419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Feng, Y.; Li, J.; Yue, S.; Zhang, X.; Hu, B.; Du, H. Recollision dynamics analysis of high–order harmonic generation in solids. Phys. Rev. A 2020, 101, 023402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanin, A.A.; Stepanov, E.A.; Fedotov, A.B.; Zheltikov, A.M. Mapping the electron band structure by intraband high–harmonic generation in solids. Optica 2017, 4, 516–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Lan, P.; He, L.; Cao, W.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, P. Determination of Electron Band Structure using Temporal Interferometry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 124, 157403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, D.; Hansen, K.K. High–Harmonic Generation in Solids with and without Topological Edge States. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 177401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro Neto, A.H.; Guinea, F.; Peres, N.M.R.; Novoselov, K.S.; Geim, A.K. The electronic properties of graphene. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2009, 81, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geim, A.K. Graphene: Status and Prospects. Science 2009, 324, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaibley, J.R.; Yu, H.; Clark, G.; Rivera, P.; Ross, J.S.; Seyler, K.L.; Yao, W.; Xu, X. Valleytronics in 2D materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 16055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, S.A.; Nezich, D.; Varghese, J.O.; Kim, P.; Gedik, N.; Jarillo–Herrero, P.; Xiao, D.; Rothschild, M. Valleytronics: Opportunities, Challenges, and Paths Forward. Small 2018, 14, 1801483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, F.; Schmid, C.P.; Schlauderer, S.; Gmitra, M.; Fabian, J.; Nagler, P.; Schüller, C.; Korn, T.; Hawkins, P.G.; Steiner, J.T.; Huttner, U.; Koch, S.W.; Kira, M.; Huber, R. Lightwave valleytronics in a monolayer of tungsten diselenide. Nature 2018, 557, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Yao, W.; Niu, Q. Valley–Contrasting Physics in Graphene: Magnetic Moment and Topological Transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 99, 236809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, K.F.; Xiao, D.; Shan, J. Light–valley interactions in 2D semiconductors. Nat. Photon. 2018, 12, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez–Galán, Á.; Silva, R.E.F.; Smirnova, O.; Ivanov, M. Lightwave control of topological properties in 2D materials for sub–cycle and non-resonant valley manipulation. Nat. Photon. 2020, 14, 728–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez–Galán, Á.; Silva, R.E.F.; Smirnova, O.; Ivanov, M. Sub-cycle valleytronics: control of valley polarization using few-cycle linearly polarized pulses. Optica 2021, 8, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Elliott, P.; Shallcross, S. Valley control by linearly polarized laser pulses: example of WSe2. Optica 2022, 9, 947–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golub, L.; Tarasenko, S. Valley polarization induced second harmonic generation in graphene. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 90, 201402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, K.F.; McGill, K.L.; Park, J.; McEuen, P.L. The valley Hall effect in MoS2 transistors. Science 2014, 344, 1489–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mrudul, M.S.; Jiménez–Galán, Á.; Ivanov, M.; Dixit, G. Light–induced valleytronics in pristine graphene. Optica 2021, 8, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Guo, J.; Gao, F.; Liu, X. Dynamical symmetry and valley–selective circularly polarized high–harmonic generation in monolayer molybdenum disulfide. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 105, 024305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, C.; Li, R. Valley-Selective Polarization in Twisted Bilayer Graphene Controlled by a Counter-Rotating Bicircular Laser Field. Photonics 2023, 10, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, S.; Maultzsch, J.; Thomsen, C.; Ordejon, P. Tight–binding description of graphene. Phys. Rev. B 2002, 66, 035412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Wei, H.; Chen, J.; Yu, C.; Lu, R.; Lin, C.D. Effect of transition dipole phase on high–order–harmonic generation in solid materials. Phys. Rev. A 2017, 96, 053850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrovski, D.; Madsen, L.B.; Pedersen, T.G. High–order harmonic generation from gapped graphene: Perturbative response and transition to nonperturbative regime. Phys. Rev. B 2017, 95, 035405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avetissian, H.K.; Avetissian, A.K.; Avchyan, B.R.; Mkrtchian, G.F. Wave mixing and high harmonic generation at two–color multiphoton excitation in two–dimensional hexagonal nanostructures. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 100, 035434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avetissian, H.K.; Mkrtchian, G.F.; Knorr, A. Efficient high–harmonic generation in graphene with two–color laser field at orthogonal polarization. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 105, 195405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vampa, G.; McDonald, C.R.; Orlando, G.; Klug, D.D.; Corkum, P.B.; Brabec, T. Theoretical Analysis of High-Harmonic Generation in Solids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 113, 073901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Li, L.; Zhu, X.; Huang, T.; Zhang, X.; Wang, D.; Lan, P.; Lu, P. Wavelength dependence of high–order harmonic yields in solids. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 98, 063419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Li, L.; Huang, T.; Zhu, X.; Lan, P.; Lu, P. Enhancement of the photocurrents injected in gapped graphene by the orthogonally polarized two–color laser field. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 17387–17397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vampa, G.; McDonald, C.R.; Orlando, G.; Corkum, P.B.; Brabec, T. Semiclassical analysis of high harmonic generation in bulk crystals. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 91, 064302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Z.; Zhou, X.; Bian, X. High–order–harmonic generation from periodic potentials driven by few-cycle laser pulses. Phys. Rev. A 2016, 93, 033852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Feng, Y.; Fu, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Du, H. Complex carrier-envelope-phase effect of solid harmonics under nonadiabatic conditions. Phys. Rev. A 2019, 99, 023406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, D.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, X.; Lu, P. Effects of quantum interferences among crystal–momentum–resolved electrons in solid high–order harmonic generation. Phys. Rev. A 2021, 103, 033104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cireasa, R.; Boguslavskiy, A.E.; Pons, B.; Wong, M.C.H.; Descamps, D.; Petit, S.; Ruf, H.; Thiré, N.; Ferré, A.; Suarez, J.; Higuet, J.; Schmidt, B.E.; Alharbi, A.F.; Légaré, F.; Blanchet, V.; Fabre, B.; Patchkovskii, S.; Smirnova, O.; Mairesse, Y.; Bhardwaj, V.R. Probing molecular chirality on a sub–femtosecond timescale. Nat. Phys. 2015, 11, 654–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnova, O.; Mairesse, Y.; Patchkovskii, S. Opportunities for chiral discrimination using high harmonic generation in tailored laser fields. J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 2015, 48, 234005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Liu, X.; Lan, P.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Q.; Li, W.; Lu, P. Anomalous circular dichroism in high harmonic generation of stereoisomers with two chiral centers. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 24824–24835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).