Submitted:

13 September 2023

Posted:

19 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. COVID-19 infection and diabetes

3. Reasons for the increased diabetic susceptibility to COVID-19 infection

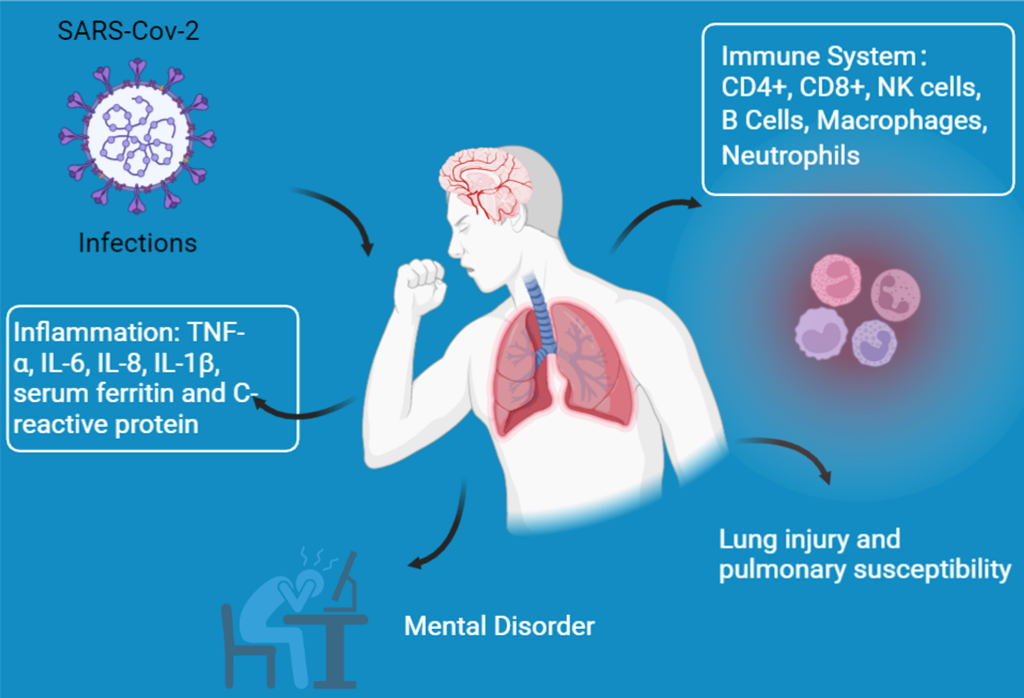

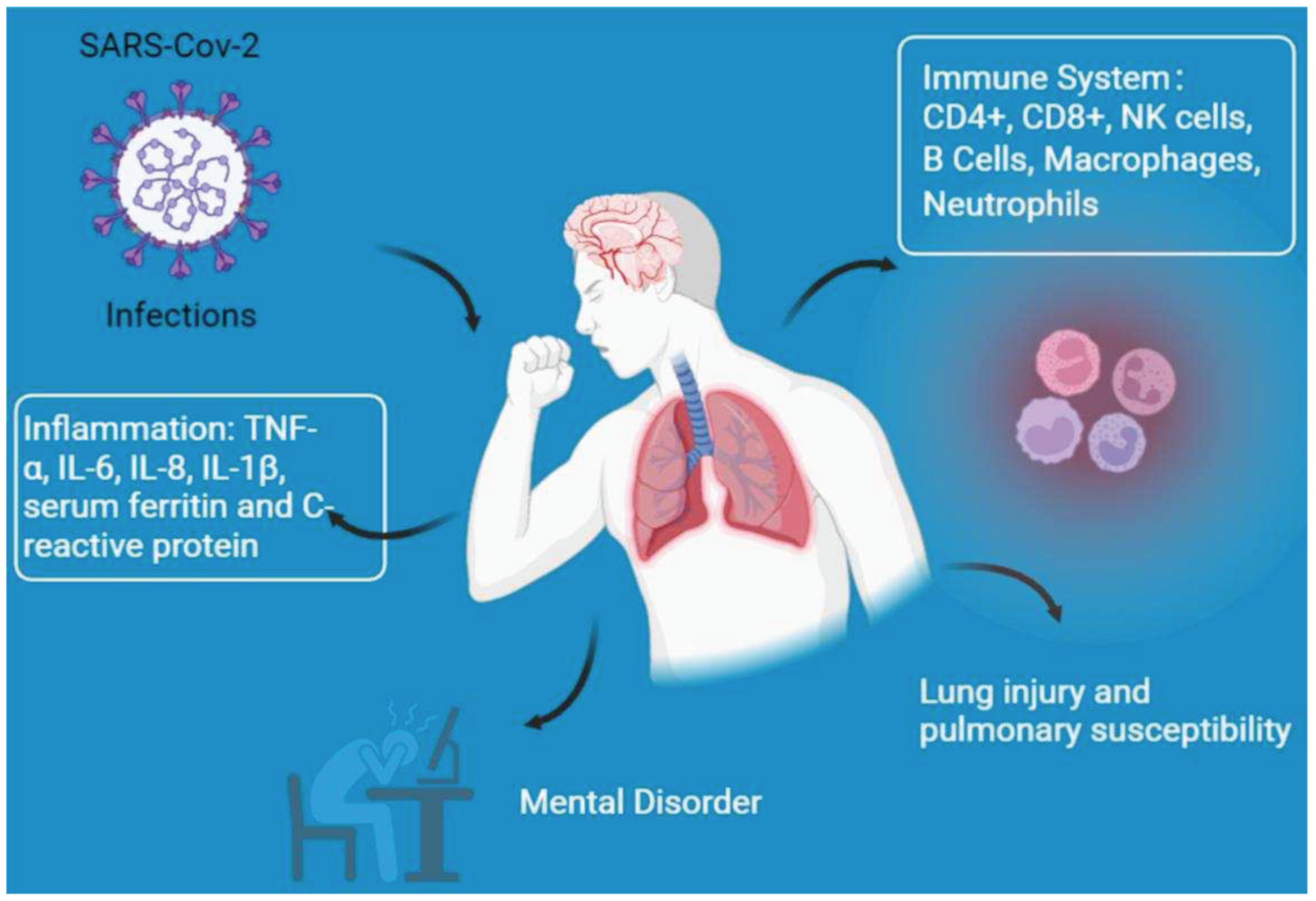

3.1. Immune system dysfunction

3.1.1. T Cells

3.1.2. Natural Killer (NK) Cells

3.1.3. B Cells

3.1.4. Macrophages

3.1.5. Neutrophils

3.2. Lung injury and pulmonary susceptibility

3.3. Inflammation

3.4. Other responses

4. Physical activity improves the resistance of diabetics to COVID-19 infection

4.1. High-intensity training

4.2. Moderate-intensity exercise

4.3. Low-intensity exercise

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Umakanthan, S.; Sahu, P.; Ranade, A.V.; Bukelo, M.M.; Rao, J.S.; Lf, A.-M.; Dahal, S.; Kumar, H.; Kv, D. Origin, transmission, diagnosis and management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Heart 2020, 96, 753–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harapan, H.; Itoh, N.; Yufika, A.; Winardi, W.; Keam, S.; Te, H.; Megawati, D.; Hayati, Z.; Wagner, A.L.; Mudatsir, M. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A literature review. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bundgaard, H.; et al. Effectiveness of adding a mask recommendation to other public health measures to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection in Danish mask wearers: a randomized controlled trial. Annals of internal medicine 2021, 174, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, I.; Lim, M.A.; Pranata, R. Diabetes mellitus is associated with increased mortality and severity of disease in COVID-19 pneumonia–a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Diabetes Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research Reviews 2020, 14, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umakanthan, S.; Senthil, S.; John, S.; Madhavan, M.K.; Das, J.; Patil, S.; Rameshwaram, R.; Cintham, A.; Subramaniam, V.; Yogi, M.; et al. The Effect of Statins on Clinical Outcome Among Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19: A Multi-Centric Cohort Study. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 742273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; et al. Obesity and diabetes as high-risk factors for severe coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19). Diabetes/metabolism research and reviews 2021, 37, e3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantzer, C.; Swendsen, J.; Maurice-Tison, S.; Salamon, R. Anxiety and depression in juvenile diabetes: A critical review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 23, 787–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corona, G.; Pizzocaro, A.; Vena, W.; Rastrelli, G.; Semeraro, F.; Isidori, A.M.; Pivonello, R.; Salonia, A.; Sforza, A.; Maggi, M. Diabetes is most important cause for mortality in COVID-19 hospitalized patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2021, 22, 275–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Story, M.J. Essential sufficiency of zinc, ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, vitamin D and magnesium for prevention and treatment of COVID-19, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, lung diseases and cancer. Biochimie 2021, 187, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scartoni, F.R.; Sant’ana, L.d.O.; Murillo-Rodriguez, E.; Yamamoto, T.; Imperatori, C.; Budde, H.; Vianna, J.M.; Machado, S. Physical Exercise and Immune System in the Elderly: Implications and Importance in COVID-19 Pandemic Period. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 593903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, R.J.; et al. Can exercise affect immune function to increase susceptibility to infection? Exercise immunology review 2020, 26, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gleeson, M.; Bishop, N.C.; Stensel, D.J.; Lindley, M.R.; Mastana, S.S.; Nimmo, M.A. The anti-inflammatory effects of exercise: mechanisms and implications for the prevention and treatment of disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golbidi, S.; Badran, M.; Laher, I. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Exercise in Diabetic Patients. Exp. Diabetes Res. 2011, 2012, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmon, P. Effects of physical exercise on anxiety, depression, and sensitivity to stress: A unifying theory. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 21, 33–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colberg, S.R.; Sigal, R.J.; Yardley, J.E.; Riddell, M.C.; Dunstan, D.W.; Dempsey, P.C.; Horton, E.S.; Castorino, K.; Tate, D.F. Physical Activity/Exercise and Diabetes: A Position Statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 2065–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laddu, D.R.; Lavie, C.J.; Phillips, S.A.; Arena, R. Physical activity for immunity protection: Inoculating populations with healthy living medicine in preparation for the next pandemic. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 64, 102–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sellami, M.; et al. Effects of acute and chronic exercise on immunological parameters in the elderly aged: can physical activity counteract the effects of aging? Frontiers in immunology 2018, 9, 2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. Regulation of NcRNA-protein binding in diabetic foot. Biomedicine Pharmacotherapy 2023, 160, 114361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukmanto, R.B.; Suharjito; Nugroho, A. ; Akbar, H. Early Detection of Diabetes Mellitus using Feature Selection and Fuzzy Support Vector Machine. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 157, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márquez-Valadez, B.; Valle-Bautista, R.; García-López, G.; Díaz, N.F.; Molina-Hernández, A. Maternal Diabetes and Fetal Programming Toward Neurological Diseases: Beyond Neural Tube Defects. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Lan, H.; Zhang, D.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Xia, P.; Tang, X.; Cai, X.; Yu, P. Research progress on ncRNAs regulation of mitochondrial dynamics in diabetes. J. Cell. Physiol. 2022, 237, 4112–4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allard, R.; Leclerc, P.; Tremblay, C.; Tannenbaum, T.-N. Diabetes and the Severity of Pandemic Influenza A (H1N1) Infection. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 1491–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, W.; Li, M.; Dong, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, C.; Qin, R.; Wang, H.; Shen, Y.; Du, K.; et al. Diabetes is a risk factor for the progression and prognosis of COVID-19. Diabetes/Metabolism Res. Rev. 2020, 36, e3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unnikrishnan, R.; Misra, A. Diabetes and COVID19: a bidirectional relationship. Nutr. Diabetes 2021, 11, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Framke, E.; Sørensen, J.K.; Andersen, P.K.; Svane-Petersen, A.C.; Alexanderson, K.; Bonde, J.P.; Farrants, K.; Flachs, E.M.; Hanson, L.L.M.; Nyberg, S.T.; et al. Contribution of income and job strain to the association between education and cardiovascular disease in 1.6 million Danish employees. Eur. Hear. J. 2019, 41, 1164–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, A.O.; et al. A single-dose intranasal ChAd vaccine protects upper and lower respiratory tracts against SARS-CoV-2. Cell 2020, 183, 169–184.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B.; Huang, S.; Zhou, J. Perspectives of Antidiabetic Drugs in Diabetes With Coronavirus Infections. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11, 592439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, E. The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19)—China, 2020. China CDC weekly 2020, 2, 113. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 2020, 8, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.J.; Ni, Z.Y.; Hu, Y.; Liang, W.H.; Ou, C.Q.; He, J.X.; Liu, L.; Shan, H.; Lei, C.L.; Hui, D.S.C.; et al. China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Covid-19. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1708–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-J.; et al. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China. Allergy 2020, 75, 1730–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grasselli, G.; et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA 2020, 323, 1574–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.K.; Gupta, R.; Misra, A. Comorbidities in COVID-19: Outcomes in hypertensive cohort and controversies with renin angiotensin system blockers. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatraju, P.K.; Ghassemieh, B.J.; Nichols, M.; Kim, R.; Jerome, K.R.; Nalla, A.K.; Greninger, A.L.; Pipavath, S.; Wurfel, M.M.; Evans, L.; et al. Covid-19 in Critically Ill Patients in the Seattle Region—Case Series. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2012–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, E.; Bakhai, C.; Kar, P.; Weaver, A.; Bradley, D.; Ismail, H.; Knighton, P.; Holman, N.; Khunti, K.; Sattar, N.; et al. Associations of type 1 and type 2 diabetes with COVID-19-related mortality in England: a whole-population study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. Comorbid diabetes mellitus was associated with poorer prognosis in patients with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. MedRxiv, 2020.

- Roncon, L.; Zuin, M.; Rigatelli, G.; Zuliani, G. Diabetic patients with COVID-19 infection are at higher risk of ICU admission and poor short-term outcome. J. Clin. Virol. 2020, 127, 104354–104354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdi, A.; Jalilian, M.; Sarbarzeh, P.A.; Vlaisavljevic, Z. Diabetes and COVID-19: A systematic review on the current evidences. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pr. 2020, 166, 108347–108347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berbudi, A.; et al. Type 2 diabetes and its impact on the immune system. Current diabetes reviews 2020, 16, 442. [Google Scholar]

- Frydrych, L.M.; Bian, G.; E O’lone, D.; A Ward, P.; Delano, M.J. Obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus drive immune dysfunction, infection development, and sepsis mortality. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2018, 104, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrie, J.; Guzik, T.J.; Touyz, R.M. Diabetes, Hypertension, and Cardiovascular Disease: Clinical Insights and Vascular Mechanisms. Can. J. Cardiol. 2017, 34, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, D.; Dai, Z.; Li, X. Association Between Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index and Diabetic Depression. Clin. Interv. Aging 2021, 16, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thurlow, L.R.; Stephens, A.C.; Hurley, K.E.; Richardson, A.R. Lack of nutritional immunity in diabetic skin infections promotes Staphylococcus aureus virulence. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabc5569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, B.J.; Jaffe, A.; Hameed, S.; Verge, C.F.; Waters, S.; Widger, J. Cystic fibrosis-related diabetes and lung disease: an update. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2021, 30, 200293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dryden, M.; Baguneid, M.; Eckmann, C.; Corman, S.; Stephens, J.; Solem, C.; Li, J.; Charbonneau, C.; Baillon-Plot, N.; Haider, S. Pathophysiology and burden of infection in patients with diabetes mellitus and peripheral vascular disease: focus on skin and soft-tissue infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015, 21, S27–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’toole, P.; Maltenfort, M.G.; Chen, A.F.; Parvizi, J. Projected Increase in Periprosthetic Joint Infections Secondary to Rise in Diabetes and Obesity. J. Arthroplast. 2016, 31, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, L.; Karakiulakis, G.; Roth, M. Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection? The lancet respiratory medicine 2020, 8, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navand, A.H.; et al. Diabetes and coronavirus infections (SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2). Journal of Acute Disease 2020, 9, 244. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, R.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, S.; Wang, C.; Liu, J.; Gao, L.; Hu, Z.; Fei, J.; et al. Distinguishable Immunologic Characteristics of COVID-19 Patients with Comorbid Type 2 Diabetes Compared with Nondiabetic Individuals. Mediat. Inflamm. 2020, 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobashir, M.; Helmi, N.; Alammari, D. Role of Potential COVID-19 Immune System Associated Genes and the Potential Pathways Linkage with Type-2 Diabetes. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2022, 25, 2452–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alguwaihes, A.M.; Al-Sofiani, M.E.; Megdad, M.; Albader, S.S.; Alsari, M.H.; Alelayan, A.; Alzahrani, S.H.; Sabico, S.; Al-Daghri, N.M.; Jammah, A.A. Diabetes and Covid-19 among hospitalized patients in Saudi Arabia: a single-centre retrospective study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2020, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfella, R.; D'Onofrio, N.; Sardu, C.; Scisciola, L.; Maggi, P.; Coppola, N.; Romano, C.; Messina, V.; Turriziani, F.; Siniscalchi, M.; et al. Does poor glycaemic control affect the immunogenicity of the COVID-19 vaccination in patients with type 2 diabetes: The CAVEAT study. Diabetes, Obes. Metab. 2021, 24, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.; Ye, S.; Wang, W.; Li, S.; Hu, Q.; Masaki, T. Clinical Features of COVID-19 Patients with Diabetes and Secondary Hyperglycemia. J. Diabetes Res. 2020, 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasr El-Din, A.; et al. Impact of high serum levels of MMP-7, MMP-9, TGF-β and PDGF macrophage activation markers on severity of COVID-19 in obese-diabetic patients. Infection and Drug Resistance 2021, 4015–4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhandari, S.; Rankawat, G.; Singh, A.; Gupta, V.; Kakkar, S. Impact of glycemic control in diabetes mellitus on management of COVID-19 infection. Int. J. Diabetes Dev. Ctries. 2020, 40, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, F.; Ren, H.; Zhang, S.; Shi, X.; Yu, X.; Dong, K. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with severe covid-19 with diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2020, 8, e001343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sofiani, M.E.; Albunyan, S.; Alguwaihes, A.M.; Kalyani, R.R.; Golden, S.H.; Alfadda, A. Determinants of mental health outcomes among people with and without diabetes during the COVID-19 outbreak in the Arab Gulf Region. J. Diabetes 2020, 13, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajele, W.K.; Oladejo, T.A.; Akanni, A.A.; Babalola, O.B. Spiritual intelligence, mindfulness, emotional dysregulation, depression relationship with mental well-being among persons with diabetes during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2021, 20, 1705–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, K.; Morris, J.; Bridson, T.; Govan, B.; Rush, C.; Ketheesan, N. Immunological mechanisms contributing to the double burden of diabetes and intracellular bacterial infections. Immunology 2015, 144, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, T.; Ackerman, S.E.; Shen, L.; Engleman, E. Role of innate and adaptive immunity in obesity-associated metabolic disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownlee, M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature 2001, 414, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-M.; Kim, J.-J.; Kim, H.J.; Shong, M.; Ku, B.J.; Jo, E.-K. Upregulated NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes 2012, 62, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, J.S.; Ferreira, D.; Paige, E.; Gedye, C.; Boyle, M. Infectious Complications of Biological and Small Molecule Targeted Immunomodulatory Therapies. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekoua, M.P.; et al. Modulation of immune cells and Th1/Th2 cytokines in insulin-treated type 2 diabetes mellitus. African health sciences 2016, 16, 712–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sell, H.; Habich, C.; Eckel, J. Adaptive immunity in obesity and insulin resistance. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2012, 8, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asadikaram, G.; et al. The study of the serum level of IL-4, TGF-β, IFN-γ, and IL-6 in overweight patients with and without diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry 2019, 120, 4147–4157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sireesh, D.; Dhamodharan, U.; Ezhilarasi, K.; Vijay, V.; Ramkumar, K.M. Association of NF-E2 Related Factor 2 (Nrf2) and inflammatory cytokines in recent onset Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Rudensky, A.Y. Foxp3 in control of the regulatory T cell lineage. Nat. Immunol. 2007, 8, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-Y.; et al. Treatment of foot disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus using human umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cells: response and correction of immunological anomalies. Current Pharmaceutical Design 2013, 19, 4893–4899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Ruan, S.; Yin, L.; Zhao, D.; Chen, C.; Pan, B.; Zeng, L.; Li, Z.; Xu, K. Dynamic regulation of effector IFN-γ-producing and IL-17-producing T cell subsets in the development of acute graft-versus-host disease. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 13, 1395–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavazović, I.; Krapić, M.; Beumer-Chuwonpad, A.; Polić, B.; Wensveen, T.T.; Lemmermann, N.A.; van Gisbergen, K.P.; Wensveen, F.M. Hyperglycemia and Not Hyperinsulinemia Mediates Diabetes-Induced Memory CD8 T-Cell Dysfunction. Diabetes 2022, 71, 706–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoni, A.; Salvati, L.; Maggi, L.; Capone, M.; Vanni, A.; Spinicci, M.; Mencarini, J.; Caporale, R.; Peruzzi, B.; Antonelli, A.; et al. Impaired immune cell cytotoxicity in severe COVID-19 is IL-6 dependent. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 4694–4703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Qin, C.-J.; Wu, M.-Z.; Liu, F.-F.; Liu, S.-S.; Liu, L. The Frequency of Natural Killer Cell Subsets in Patients with Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome with Deep Fungal Infections. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colucci, F.; Caligiuri, M.A.; Di Santo, J.P. What does it take to make a natural killer? Nature Reviews Immunology 2003, 3, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berrou, J.; Fougeray, S.; Venot, M.; Chardiny, V.; Gautier, J.-F.; Dulphy, N.; Toubert, A.; Peraldi, M.-N. Natural Killer Cell Function, an Important Target for Infection and Tumor Protection, Is Impaired in Type 2 Diabetes. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e62418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, M.; Ma, K.; Wang, X.; Yan, W.; Wang, H.; You, J.; Wang, Q.; Chen, H.; Guo, W.; Chen, T.; et al. Immunological Characteristics in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Among COVID-19 Patients. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 596518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.R.; Haas, K.M.; A Beck, M.; Teague, H. The effects of diet-induced obesity on B cell function. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2014, 179, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winer, D.A.; Winer, S.; Shen, L.; Wadia, P.P.; Yantha, J.; Paltser, G.; Tsui, H.; Wu, P.; Davidson, M.G.; Alonso, M.N.; et al. B cells promote insulin resistance through modulation of T cells and production of pathogenic IgG antibodies. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Wit, J.; Souwer, Y.; Jorritsma, T.; Bos, H.K.; Brinke, A.T.; Neefjes, J.; van Ham, S.M. Antigen-Specific B Cells Reactivate an Effective Cytotoxic T Cell Response against Phagocytosed Salmonella through Cross-Presentation. PLOS ONE 2010, 5, e13016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, R.; Banerjee, M. Are people with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus at high risk of reinfections with COVID-19? Primary care diabetes 2021, 15, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.; et al. B cell responses to influenza infection and vaccination. Influenza Pathogenesis and Control-Volume II, 2014: p. 381-398.

- Jagannathan, M.; McDonnell, M.; Liang, Y.; Hasturk, H.; Hetzel, J.; Rubin, D.; Kantarci, A.; Van Dyke, T.E.; Ganley-Leal, L.M.; Nikolajczyk, B.S. Toll-like receptors regulate B cell cytokine production in patients with diabetes. Diabetologia 2010, 53, 1461–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Huang, X.; Sun, J.; Xie, T.; Lei, Y.; Muhammad, J.; Li, X.; Zeng, X.; Zhou, F.; Qin, H.; et al. Clinical Characteristics and Immune Injury Mechanisms in 71 Patients with COVID-19. mSphere 2020, 5, e00362–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; et al. Hypertension and diabetes delay the viral clearance in COVID-19 patients. MedRxiv, 2020.

- Cronstein, B.N.; Sitkovsky, M. Adenosine and adenosine receptors in the pathogenesis and treatment of rheumatic diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2016, 13, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravi, J.; Elbaz, M.; Wani, N.A.; Nasser, M.W.; Ganju, R.K. Cannabinoid receptor-2 agonist inhibits macrophage induced EMT in non-small cell lung cancer by downregulation of EGFR pathway. Mol. Carcinog. 2016, 55, 2063–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Restrepo, B.I.; Twahirwa, M.; Rahbar, M.H.; Schlesinger, L.S. Phagocytosis via Complement or Fc-Gamma Receptors Is Compromised in Monocytes from Type 2 Diabetes Patients with Chronic Hyperglycemia. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e92977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlou, S.; Lindsay, J.; Ingram, R.; Xu, H.; Chen, M. Sustained high glucose exposure sensitizes macrophage responses to cytokine stimuli but reduces their phagocytic activity. BMC Immunol. 2018, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggiolini, M.; Dewald, B.; Moser, B. Human Chemokines: An Update. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1997, 15, 675–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kida, K.; Utsuyama, M.; Takizawa, T.; Thurlbeck, W.M. Changes in Lung Morphologic Features and Elasticity Caused by Streptozotocin-induced Diabetes Mellitus in Growing Rats1–3. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1983, 128, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Shi, L.; Wang, X.; Yu, X.; Wang, D. Sp1 transcription factor represses transcription of phosphatase and tensin homolog to aggravate lung injury in mice with type 2 diabetes mellitus-pulmonary tuberculosis. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 9928–9944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruglikov, I.L.; Shah, M.; E Scherer, P. Obesity and diabetes as comorbidities for COVID-19: Underlying mechanisms and the role of viral–bacterial interactions. eLife 2020, 9, e61330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Wu, J.; Jin, Z.; Yan, L.-J. Potential Biochemical Mechanisms of Lung Injury in Diabetes. Aging Dis. 2017, 8, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kuraishy, H.M.; Al-Gareeb, A.I.; Alblihed, M.; Cruz-Martins, N.; Batiha, G.E.-S. COVID-19 and Risk of Acute Ischemic Stroke and Acute Lung Injury in Patients With Type II Diabetes Mellitus: The Anti-inflammatory Role of Metformin. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 644295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Du, Z.; Zhu, F. Glycosylated hemoglobin is associated with systemic inflammation, hypercoagulability, and prognosis of COVID-19 patients. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pr. 2020, 164, 108214–108214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Registry, C.C.T., A multicenter, randomized controlled trial for the efficacy and safety of tocilizumab in the treatment of new coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19), 2020.

- Targher, G.; Mantovani, A.; Wang, X.-B.; Yan, H.-D.; Sun, Q.-F.; Pan, K.-H.; Byrne, C.D.; Zheng, K.I.; Chen, Y.-P.; Eslam, M.; et al. Patients with diabetes are at higher risk for severe illness from COVID-19. Diabetes Metab. 2020, 46, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens-Gary, M.D.; et al. The importance of addressing depression and diabetes distress in adults with type 2 diabetes. Journal of general internal medicine 2019, 34, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, N.; Meng, H.; Liu, T.; Feng, Y.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wang, H. Blueberry Phenolics Reduce Gastrointestinal Infection of Patients with Cerebral Venous Thrombosis by Improving Depressant-Induced Autoimmune Disorder via miR-155-Mediated Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 853–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaremka, L.M.; Fagundes, C.P.; Glaser, R.; Bennett, J.M.; Malarkey, W.B.; Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K. Loneliness predicts pain, depression, and fatigue: Understanding the role of immune dysregulation. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2013, 38, 1310–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudenstine, S.; et al. Depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic in an urban, low-income public university sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress 2021, 34, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; Yan, C.; Lee, P.; Sun, H.; Yu, F.-S. Dendritic cell dysfunction and diabetic sensory neuropathy in the cornea. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 1998–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Liu, P.; Zhang, X.; Bao, T.; Wang, T.; Guo, L.; Li, Y.; Dong, X.; Li, X.; Dong, Y.; et al. Inulin and Lycium barbarum polysaccharides ameliorate diabetes by enhancing gut barrier via modulating gut microbiota and activating gut mucosal TLR2+ intraepithelial γδ T cells in rats. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 79, 104407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukas, H.; Xu, C.; Yu, Y.; Gao, W. Emerging Telemedicine Tools for Remote COVID-19 Diagnosis, Monitoring, and Management. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 16180–16193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S. Can moderate intensity aerobic exercise be an effective and valuable therapy in preventing and controlling the pandemic of COVID-19? Medical hypotheses 2020, 143, 109854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halle, M.; et al. Exercise and sports after COVID-19—Guidance from a clinical perspective. Translational Sports Medicine 2021, 4, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopps, E.; Canino, B.; Caimi, G. Effects of exercise on inflammation markers in type 2 diabetic subjects. Acta Diabetol. 2011, 48, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denou, E.; Marcinko, K.; Surette, M.G.; Steinberg, G.R.; Schertzer, J.D. High-intensity exercise training increases the diversity and metabolic capacity of the mouse distal gut microbiota during diet-induced obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 310, E982–E993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrega-Mouquinho, Y.; Sánchez-Gómez, J.; Fuentes-García, J.P.; Collado-Mateo, D.; Villafaina, S. Effects of High-Intensity Interval Training and Moderate-Intensity Training on Stress, Depression, Anxiety, and Resilience in Healthy Adults During Coronavirus Disease 2019 Confinement: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 643069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford, K.I.; Goodyear, L.J. Exercise and type 2 diabetes: molecular mechanisms regulating glucose uptake in skeletal muscle. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2014, 38, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidu, S.; Khunti, K.; Yates, T.; Almaqhawi, A.; Davies, M.; Sargeant, J. The importance of physical activity in management of type 2 diabetes and COVID-19. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 12, 20420188211054686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amini, H.; Habibi, S.; Islamoglu, A.H.; Isanejad, E.; Uz, C.; Daniyari, H. COVID-19 pandemic-induced physical inactivity: the necessity of updating the Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018-2030. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2021, 26, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amini, H.; Isanejad, A.; Chamani, N.; Movahedi-Fard, F.; Salimi, F.; Moezi, M.; Habibi, S. Physical activity during COVID-19 pandemic in the Iranian population: A brief report. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1.9 million participants. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e1077–e1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhan, R.; Agrawal, A.; Sharma, M. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress during COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of neurosciences in rural practice 2020, 11, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappa, S.; Ntella, V.; Giannakas, T.; Giannakoulis, V.G.; Papoutsi, E.; Katsaounou, P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbay, R.Y.; Kurtulmuş, A.; Arpacıoğlu, S.; Karadere, E. Depression, anxiety, stress levels of physicians and associated factors in Covid-19 pandemics. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 290, 113130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohm, T.V.; et al. Inflammation in obesity, diabetes, and related disorders. Immunity 2022, 55, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P.; Gupta, M.; Katoch, N.; Garg, K.; Garg, B. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Diabetes Associated Mortality in Patients with COVID-19. Int. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 19, e113220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, D.E.; et al. High-intensity interval training in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Current Atherosclerosis Reports 2019, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guiraud, T.; Nigam, A.; Gremeaux, V.; Meyer, P.; Juneau, M.; Bosquet, L. High-Intensity Interval Training in Cardiac Rehabilitation. Sports Med. 2012, 42, 587–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhu, L.; Su, Y. Comparative Effectiveness of High-Intensity Interval Training and Moderate-Intensity Continuous Training for Cardiometabolic Risk Factors and Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Childhood Obesity: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuan, T.-C.; Hsu, T.-G.; Fong, M.-C.; Hsu, C.-F.; Tsai, K.K.C.; Lee, C.-Y.; Kong, C.-W. Deleterious effects of short-term, high-intensity exercise on immune function: evidence from leucocyte mitochondrial alterations and apoptosis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2007, 42, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, G.I.; Khan, Q.; Drysdale, P.T.; Wallace, F.; Jeukendrup, A.E.; Drayson, M.T.; Gleeson, M. Effect of prolonged exercise and carbohydrate ingestion on type 1 and type 2 T lymphocyte distribution and intracellular cytokine production in humans. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005, 98, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, E.; Bateman, E. Ultramarathon running and upper respiratory tract infections-an epidemiological survey. South African Medical Journal 1983, 64, 582–584. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Campbell, J.P.; Turner, J.E. Debunking the Myth of Exercise-Induced Immune Suppression: Redefining the Impact of Exercise on Immunological Health Across the Lifespan. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, D.B.; Slentz, C.A.; Willis, L.H.; Hoselton, A.; Huebner, J.L.; Kraus, V.B.; Moss, J.; Muehlbauer, M.J.; Spielmann, G.; Muoio, D.M.; et al. Rejuvenation of Neutrophil Functions in Association With Reduced Diabetes Risk Following Ten Weeks of Low-Volume High Intensity Interval Walking in Older Adults With Prediabetes – A Pilot Study. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Ah Morano, A.E.; Dorneles, G.P.; Peres, A.; Lira, F.S. The role of glucose homeostasis on immune function in response to exercise: The impact of low or higher energetic conditions. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020, 235, 3169–3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, E.; Durrer, C.; Simtchouk, S.; Jung, M.E.; Bourne, J.E.; Voth, E.; Little, J.P. Short-term high-intensity interval and moderate-intensity continuous training reduce leukocyte TLR4 in inactive adults at elevated risk of type 2 diabetes. J. Appl. Physiol. 2015, 119, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.-C.; Hsu, C.-C.; Chiu, C.-C.; Lin, H.-J.; Wang, J.-J.; Weng, S.-F. Association between exercise and health-related quality of life and medical resource use in elderly people with diabetes: a cross-sectional population-based study. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. Physical activity and health in the presence of China's economic growth: meeting the public health challenges of the aging population. Journal of sport and health science 2016, 5, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira, É.; Marinho, D.A.; Neiva, H.P.; Lourenço, O. Inflammatory Effects of High and Moderate Intensity Exercise—A Systematic Review. Front. Physiol. 2020, 10, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radak, Z.; Ishihara, K.; Tekus, E.; Varga, C.; Posa, A.; Balogh, L.; Boldogh, I.; Koltai, E. Exercise, oxidants, and antioxidants change the shape of the bell-shaped hormesis curve. Redox Biol. 2017, 12, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobianchi, S.; Arbat-Plana, A.; Lopez-Alvarez, V.M.; Navarro, X. Neuroprotective Effects of Exercise Treatments After Injury: The Dual Role of Neurotrophic Factors. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2017, 15, 495–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zar, A.; Ahmadi, F.; Miri, M.; Abedi, H.A.; Salesi, M. Cytokine Pattern is Affected by Training Intensity in Women Futsal Players. Immune Netw. 2016, 16, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wing, R.R.; Epstein, L.H.; Paternostro-Bayles, M.; Kriska, A.; Nowalk, M.P.; Gooding, W. Exercise in a behavioural weight control programme for obese patients with Type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes. Diabetologia 1988, 31, 902–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Liu, J.; Yan, H. Medium-intensity acute exhaustive exercise induces neural cell apoptosis in the rat hippocampus. Neural regeneration research 2013, 8, 127–132. [CrossRef]

- Parker, L.; Shaw, C.S.; Banting, L.; Levinger, I.; Hill, K.M.; McAinch, A.J.; Stepto, N.K. Acute Low-Volume High-Intensity Interval Exercise and Continuous Moderate-Intensity Exercise Elicit a Similar Improvement in 24-h Glycemic Control in Overweight and Obese Adults. Front. Physiol. 2017, 7, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vickers, K.S.; Patten, C.A.; Lewis, B.A.; Clark, M.M.; Ussher, M.; Ebbert, J.O.; Croghan, I.T.; Decker, P.A.; Hathaway, J.; Marcus, B.H.; et al. Feasibility of an exercise counseling intervention for depressed women smokers. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2009, 11, 985–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraha, B.; Chaves, A.R.; Kelly, L.P.; Wallack, E.M.; Wadden, K.P.; McCarthy, J.; Ploughman, M. A Bout of High Intensity Interval Training Lengthened Nerve Conduction Latency to the Non-exercised Affected Limb in Chronic Stroke. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, B.; Hayney, M.S.; Muller, D.; Rakel, D.; Brown, R.; Zgierska, A.E.; Barlow, S.; Hayer, S.; Barnet, J.H.; Torres, E.R.; et al. Meditation or exercise for preventing acute respiratory infection (MEPARI-2): A randomized controlled trial. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0197778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro-Viña, C.; Valentín, J.; Fernández, L.; González-Vicent, M.; Pérez-Ruiz, M.; Lucía, A.; Culos-Reed, S.N.; Díaz, M. .; Pérez-Martínez, A. Influence of a Moderate-Intensity Exercise Program on Early NK Cell Immune Recovery in Pediatric Patients After Reduced-Intensity Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2016, 16, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khammassi, M.; Ouerghi, N.; Said, M.; Feki, M.; Khammassi, Y.; Pereira, B.; Thivel, D.; Bouassida, A. Continuous Moderate-Intensity but Not High-Intensity Interval Training Improves Immune Function Biomarkers in Healthy Young Men. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hekmatikar, A.H.A.; et al. Exercise in an overweight patient with COVID-19: a case study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 5882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piquet, V.; Luczak, C.; Seiler, F.; Monaury, J.; Martini, A.; Ward, A.B.; Gracies, J.-M.; Motavasseli, D.; Lépine, E.; Chambard, L.; et al. Do Patients With COVID-19 Benefit from Rehabilitation? Functional Outcomes of the First 100 Patients in a COVID-19 Rehabilitation Unit. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabilitation 2021, 102, 1067–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jesus, I.; Vanhee, V.; Deramaudt, T.B.; Bonay, M. Promising effects of exercise on the cardiovascular, metabolic and immune system during COVID-19 period. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2020, 35, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rykova, M.; et al. The activation processes of the immune system during low intensity exercise without relaxation. Rossiiskii Fiziologicheskii Zhurnal Imeni IM Sechenova 2008, 94, 212–219. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, A. IDF21-0163 The usefulness of low-intensity physical activity management for malaise in type 2 diabetic patients after ablation. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Yang, J.; Lin, L.; Chen, S. Physical Exercise Ameliorates Anxiety, Depression and Sleep Quality in College Students: Experimental Evidence from Exercise Intensity and Frequency. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tunkamnerdthai, O.; Auvichayapat, P.; Donsom, M.; Leelayuwat, N. Improvement of pulmonary function with arm swing exercise in patients with type 2 diabetes. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2015, 27, 649–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Model | Age | Research findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| HWD | NDM: 62.1 T2DP: 63.4 | Neutrophil, LS, IgE, IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-6 ↑ T, Tc, Th, and NK cells ↓ |

[49] |

| Diabetic patients | SMARCD3, PARL, GLIPR1, STAT2, PMAIP1, GP1BA, and TOX genes and PI3K-Akt, focal adhesion, Foxo, phagosome, adrenergic, osteoclast differentiation, platelet activation, insulin, cytokine- cytokine interaction, apoptosis, ECM, JAK-STAT, and oxytocin signaling were the linkage between COVID-19 and Type-2 diabetes | [50] | |

| Diabetic patients | Median age: 55 | Creatinine, neutrophil, creatinine, alanine aminotransferase ↑ | [51] |

| HWD | Range from 18 to 60 | CD4+ T cells, CD4+/TNF-α, CD4+/IL-2, CD4+/IFN-γ ↓ | [52] |

| HWD | Median age: 47 | CD3+, CD4+, CD4+/CD8+ ↑ hs-CRP、LDH、IL-6、CD8+ ↓ |

[53] |

| HWD | MMP-7, MMP-9, PDGF and TGF-β ↑ LBP↓ |

[54] | |

| PUCD | Median age: 61.45 | uncontrolled inflammatory responses, leukocyte, neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio, IL-6, FDP, D-dimer ↑ pulmonary invasion |

[55] |

| Patients with severe covid-19 | Median age: 64 | Susceptible to receiving mechanical ventilation and admission to ICU Mortality, leukocyte, neutrophil, high-sensitivity C reaction protein, procalcitonin, ferritin, IL-2 receptor, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, D-dimer, fibrinogen, lactic dehydrogenase and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide ↑ |

[56] |

| HWD | Depression and anxiety ↑ | [57] | |

| HWD | Median age: 40.31 | Emotional dysregulation Depression ↑ |

[58] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).