Submitted:

15 September 2023

Posted:

18 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

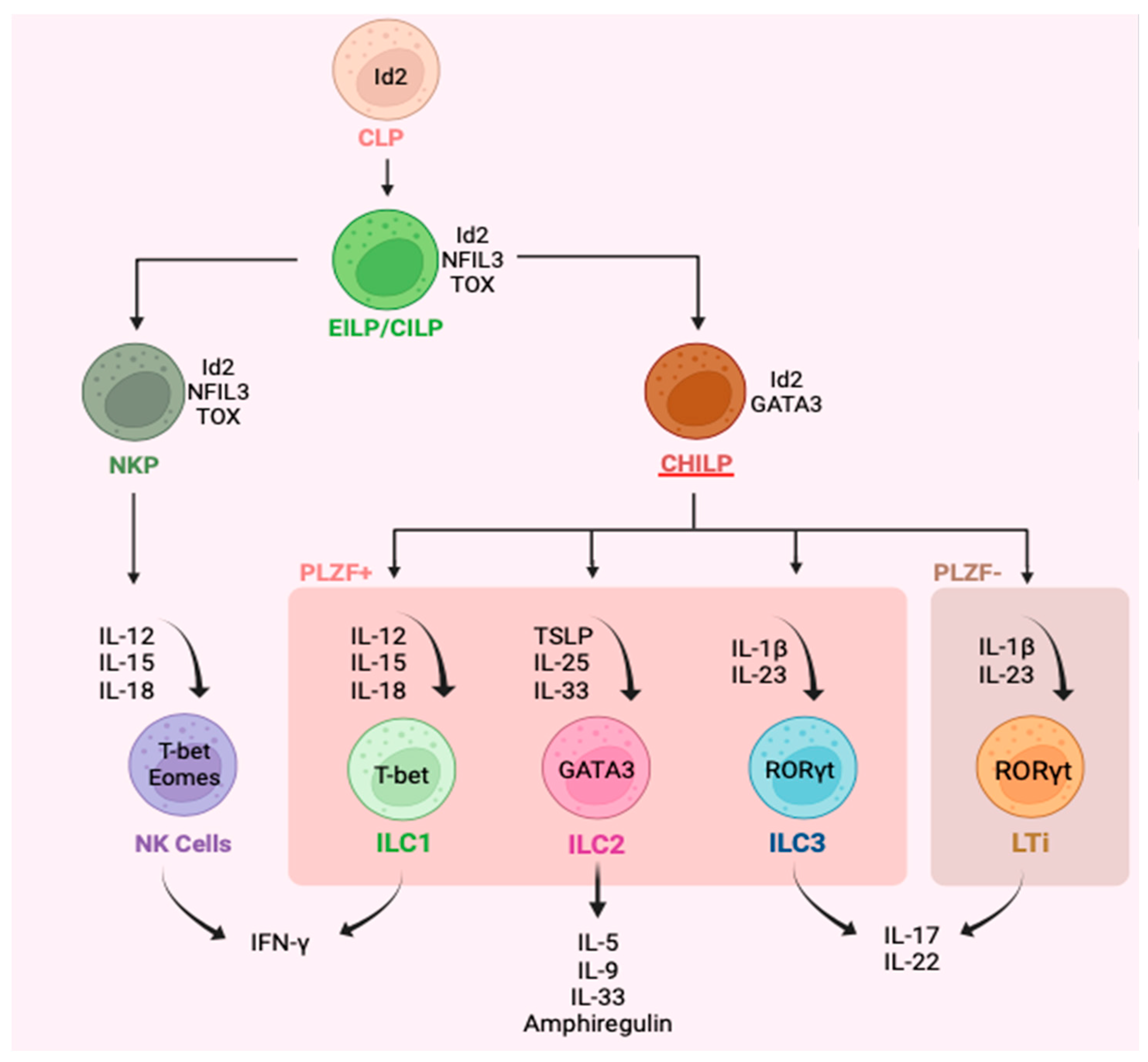

1. Introduction

2. Asthma and Type 2 Inflammation

3. Plasticity of ILC

4. Interleukin-10

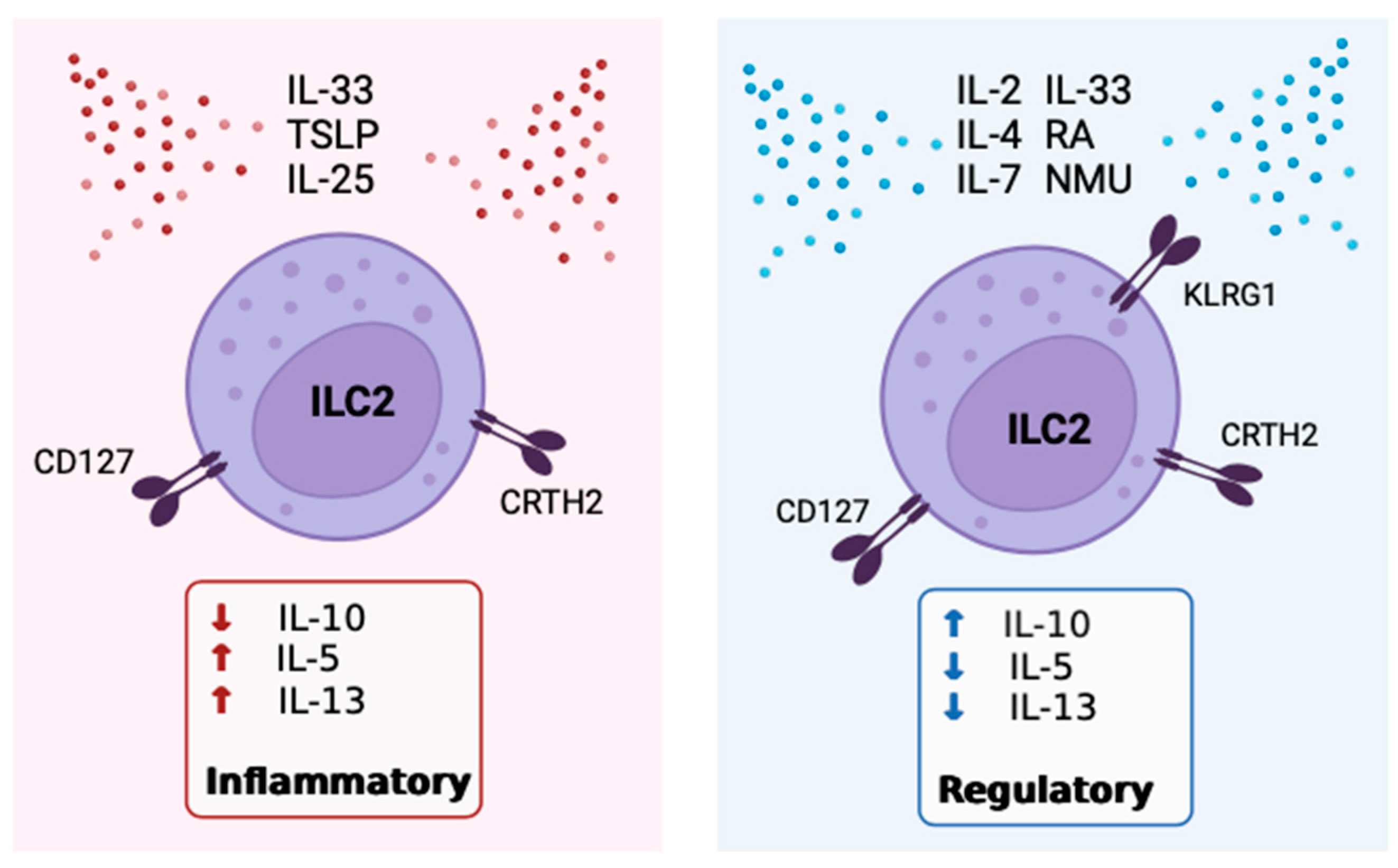

5. The Role of IL-10 Expressing ILC2

6. Positive Modulators of IL-10 Expression by ILC2

7. Inhibitors of IL-10 Expression By ILC2

8. Receptors, Sex Disparities & Neuroimmune Control OF IL-10+ILC2

9. Mechanisms Associated with IL-10 Expressing ILC2

| Study | Models and Methods | Inducers of IL-10 |

Inhibitors of IL-10 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bando J. et al. [21] | ILC2 from small intestine lamina propria of WT mice subjected to intestinal inflammation. | IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, IL-27, and NMU | TL1A |

| Seehus C. et al. [79] | WT murine blood and lung ILC2, pre-activated +/- intraperitoneal IL-33. | IL-2, IL-33, RA | TGF-β |

| Howard E. et al. [80] | Blood ILC2 from WT and RAG deficient (Rag2–/– γc–/–) in a mouse model of asthma. | IL-2, IL-4, cMaf, Blimp-1 | - |

| Golebski K. et al. [81] | Murine lung-tissue-extracted ILC2 using a model for grass pollen allergic rhinitis. Blood ILC2 from healthy controls and grass pollen allergic rhinitics. | IL-2, IL-33, RA, KLRG1 | - |

| Wang S. et al. [82] | Intestinal ILC2 from healthy and Rag1−/−Il10−/− mice and human intestinal tissue. | TGF-β | - |

| Boonpiyathad T. et al. [94] | PBMC from subjects with allergic rhinitis undergoing AIT. | RA, CD25, CTLA-4 | - |

| Baban B. et al. [98] | Examined CSF of traumatic brain injury patients and model mice and analyzed effect of metformin. | KLRG1, IL-2, IL-33, AMPK |

- |

| Laurent P. et al. [106] | Skin biopsies and peripheral blood of systemic sclerosis patients. | KLRG1 | TGF-β |

| Hurrell BP. et al. [114] | Asthma model mice, and ICAM-1 deficient mice challenged intranasally with IL-33. | - | ICAM-1 |

| Naito M. et al. [116] | Isolated lung ILC2 from WT, allergic lung inflammation model mice and Sema6D deficient mice. | - | Sema6D |

| Morita H. et al. [121] | Isolated ILC2 from blood and nasal tissue of healthy and chronic rhinosinusitis subjects and HDM sensitized mice. | IL-2, IL-33, RA, CTLA-4 | TGF-β |

10. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Komlósi, Z.I.; van de Veen, W.; Kovács, N.; Szűcs, G.; Sokolowska, M.; O’Mahony, L.; Akdis, M.; Akdis, C.A. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Allergic Asthma. Mol Aspects Med 2022, 85, 100995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ni, B. IL-10-Producing ILCs: Molecular Mechanisms and Disease Relevance. Frontiers in Immunology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boos, M.D.; Yokota, Y.; Eberl, G.; Kee, B.L. Mature Natural Killer Cell and Lymphoid Tissue–Inducing Cell Development Requires Id2-Mediated Suppression of E Protein Activity. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2007, 204, 1119–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartemes, K.R.; Kita, H. Roles of Innate Lymphoid Cells (ILCs) in Allergic Diseases: The 10-Year Anniversary for ILC2s. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2021, 147, 1531–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spits, H.; Artis, D.; Colonna, M.; Diefenbach, A.; Di Santo, J.P.; Eberl, G.; Koyasu, S.; Locksley, R.M.; McKenzie, A.N.J.; Mebius, R.E.; et al. Innate Lymphoid Cells — a Proposal for Uniform Nomenclature. Nat Rev Immunol 2013, 13, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasteiger, G.; Fan, X.; Dikiy, S.; Lee, S.Y.; Rudensky, A.Y. Tissue Residency of Innate Lymphoid Cells in Lymphoid and Nonlymphoid Organs. Science 2015, 350, 981–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonne-Année, S.; Bush, M.C.; Nutman, T.B. Differential Modulation of Human Innate Lymphoid Cell (ILC) Subsets by IL-10 and TGF-β. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 14305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.G.; Chen, R.; Kjarsgaard, M.; Huang, C.; Oliveria, J.-P.; O’Byrne, P.M.; Gauvreau, G.M.; Boulet, L.-P.; Lemiere, C.; Martin, J.; et al. Increased Numbers of Activated Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells in the Airways of Patients with Severe Asthma and Persistent Airway Eosinophilia. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2016, 137, 75–86.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Saenz, S.A.; Zlotoff, D.A.; Artis, D.; Bhandoola, A. Cutting Edge: Natural Helper Cells Derive from Lymphoid Progenitors. The Journal of Immunology 2011, 187, 5505–5509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zook, E.C.; Kee, B.L. Development of Innate Lymphoid Cells. Nat Immunol 2016, 17, 775–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seillet, C.; Rankin, L.; Groom, J.; Mielke, L.; Tellier, J.; Chopin, M.; Huntington, N.; Belz, G.; Carotta, S. Nfil3 Is Required for the Development of All Innate Lymphoid Cell Subsets. The Journal of experimental medicine 2014, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Li, F.; Harly, C.; Xing, S.; Ye, L.; Xia, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Yu, S.; Zhou, X.; et al. TCF-1 Upregulation Identifies Early Innate Lymphoid Progenitors in the Bone Marrow. Nat Immunol 2015, 16, 1044–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seehus, C.R.; Aliahmad, P.; de la Torre, B.; Iliev, I.D.; Spurka, L.; Funari, V.A.; Kaye, J. The Development of Innate Lymphoid Cells Requires TOX-Dependent Generation of a Common Innate Lymphoid Cell Progenitor. Nat Immunol 2015, 16, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klose, C.S.N.; Flach, M.; Möhle, L.; Rogell, L.; Hoyler, T.; Ebert, K.; Fabiunke, C.; Pfeifer, D.; Sexl, V.; Fonseca-Pereira, D.; et al. Differentiation of Type 1 ILCs from a Common Progenitor to All Helper-like Innate Lymphoid Cell Lineages. Cell 2014, 157, 340–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, K.; Chandler, K.J.; Spaulding, C.; Zandi, S.; Sigvardsson, M.; Graves, B.J.; Kee, B.L. Gene Deregulation and Chronic Activation in Natural Killer Cells Deficient in the Transcription Factor ETS1. Immunity 2012, 36, 921–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Male, V.; Nisoli, I.; Kostrzewski, T.; Allan, D.S.J.; Carlyle, J.R.; Lord, G.M.; Wack, A.; Brady, H.J.M. The Transcription Factor E4bp4/Nfil3 Controls Commitment to the NK Lineage and Directly Regulates Eomes and Id2 Expression. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2014, 211, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.K.; Colonna, M. Innate Lymphoid Cells in Mucosal Immunity. Frontiers in Immunology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, A.; Le Friec, G.; Cardone, J.; Kemper, C. The Th1 Life Cycle: Molecular Control of IFN-γ to IL-10 Switching. Trends in Immunology 2011, 32, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.-S.; Macatonia, S.E.; Tripp, C.S.; Wolf, S.F.; O’Garra, A.; Murphy, K.M. Development of TH1 CD4+ T Cells Through IL-12 Produced by Listeria-Induced Macrophages. Science 1993, 260, 547–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Smith, S.G.; Salter, B.; El-Gammal, A.; Oliveria, J.P.; Obminski, C.; Watson, R.; O’Byrne, P.M.; Gauvreau, G.M.; Sehmi, R. Allergen-Induced Increases in Sputum Levels of Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells in Subjects with Asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017, 196, 700–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bando, J.K.; Gilfillan, S.; Di Luccia, B.; Fachi, J.L.; Sécca, C.; Cella, M.; Colonna, M. ILC2s Are the Predominant Source of Intestinal ILC-Derived IL-10. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2019, 217, e20191520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein Wolterink, R.G.J.; Serafini, N.; Van Nimwegen, M.; Vosshenrich, C.A.J.; De Bruijn, M.J.W.; Fonseca Pereira, D.; Veiga Fernandes, H.; Hendriks, R.W.; Di Santo, J.P. Essential, Dose-Dependent Role for the Transcription Factor Gata3 in the Development of IL-5 + and IL-13 + Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110, 10240–10245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoyler, T.; Klose, C.S.N.; Souabni, A.; Turqueti-Neves, A.; Pfeifer, D.; Rawlins, E.L.; Voehringer, D.; Busslinger, M.; Diefenbach, A. The Transcription Factor GATA3 Controls Cell Fate and Maintenance of Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells. Immunity 2012, 37, 634–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mjösberg, J.; Bernink, J.; Golebski, K.; Karrich, J.J.; Peters, C.P.; Blom, B.; te Velde, A.A.; Fokkens, W.J.; van Drunen, C.M.; Spits, H. The Transcription Factor GATA3 Is Essential for the Function of Human Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells. Immunity 2012, 37, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klose, C.S.N.; Kiss, E.A.; Schwierzeck, V.; Ebert, K.; Hoyler, T.; d’Hargues, Y.; Göppert, N.; Croxford, A.L.; Waisman, A.; Tanriver, Y.; et al. A T-Bet Gradient Controls the Fate and Function of CCR6−RORγt+ Innate Lymphoid Cells. Nature 2013, 494, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salter, B.M.; Aw, M.; Sehmi, R. The Role of Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells in Eosinophilic Asthma. Journal of Leukocyte Biology 2019, 106, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernink, J.H.; Peters, C.P.; Munneke, M.; te Velde, A.A.; Meijer, S.L.; Weijer, K.; Hreggvidsdottir, H.S.; Heinsbroek, S.E.; Legrand, N.; Buskens, C.J.; et al. Human Type 1 Innate Lymphoid Cells Accumulate in Inflamed Mucosal Tissues. Nat Immunol 2013, 14, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mjösberg, J.M.; Trifari, S.; Crellin, N.K.; Peters, C.P.; van Drunen, C.M.; Piet, B.; Fokkens, W.J.; Cupedo, T.; Spits, H. Human IL-25- and IL-33-Responsive Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells Are Defined by Expression of CRTH2 and CD161. Nat Immunol 2011, 12, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennstein, S.B.; Uhrberg, M. Biology and Therapeutic Potential of Human Innate Lymphoid Cells. The FEBS Journal 2022, 289, 3967–3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallon, P.G.; Ballantyne, S.J.; Mangan, N.E.; Barlow, J.L.; Dasvarma, A.; Hewett, D.R.; McIlgorm, A.; Jolin, H.E.; McKenzie, A.N.J. Identification of an Interleukin (IL)-25–Dependent Cell Population That Provides IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 at the Onset of Helminth Expulsion. J Exp Med 2006, 203, 1105–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, W.; Lukacs, N.W.; Elesela, S.; Malinczak, C.-A. Role of ILC2 in Viral-Induced Lung Pathogenesis. Frontiers in Immunology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halim, T.; Steer, C.; Mathä, L.; Gold, M.; Martinez-Gonzalez, I.; Mcnagny, K.; McKenzie, A.N.J.; Takei, F. Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells Are Critical for the Initiation of Adaptive T Helper 2 Cell-Mediated Allergic Lung Inflammation. Immunity 2014, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartemes, K.R.; Iijima, K.; Kobayashi, T.; Kephart, G.M.; McKenzie, A.N.; Kita, H. IL-33-Responsive Lineage−CD25+CD44hi Lymphoid Cells Mediate Innate Type-2 Immunity and Allergic Inflammation in the Lungs. J Immunol 2012, 188, 1503–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, J.; Bailey, M.; Zaunders, J.; Mrad, N.; Sacks, R.; Sewell, W.; Harvey, R.J. Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells (ILC2s) Are Increased in Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps or Eosinophilia. Clin Exp Allergy 2015, 45, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, Y.; Yasuda, K.; Sakaguchi, Y.; Haneda, T.; Mizutani, H.; Yoshimoto, T.; Nakanishi, K.; Yamanishi, K. Skin-Specific Expression of IL-33 Activates Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells and Elicits Atopic Dermatitis-like Inflammation in Mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110, 13921–13926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.S.; Siracusa, M.C.; Saenz, S.A.; Noti, M.; Monticelli, L.A.; Sonnenberg, G.F.; Hepworth, M.R.; Van Voorhees, A.S.; Comeau, M.R.; Artis, D. TSLP Elicits IL-33–Independent Innate Lymphoid Cell Responses to Promote Skin Inflammation. Sci Transl Med 2013, 5, 170ra16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.L.; Fakhri, S.; Citardi, M.J.; Porter, P.C.; Corry, D.B.; Kheradmand, F.; Liu, Y.-J.; Luong, A. IL-33–Responsive Innate Lymphoid Cells Are an Important Source of IL-13 in Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013, 188, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-B.; Chen, C.-Y.; Liu, B.; Mugge, L.; Angkasekwinai, P.; Facchinetti, V.; Dong, C.; Liu, Y.-J.; Rothenberg, M.E.; Hogan, S.P.; et al. IL-25 and CD4+ TH2 Cells Enhance Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cell–Derived IL-13 Production, Which Promotes IgE-Mediated Experimental Food Allergy. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2016, 137, 1216–1225.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krempski, J.W.; Kobayashi, T.; Iijima, K.; McKenzie, A.N.; Kita, H. Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells Promote Development of T Follicular Helper (Tfh) Cells and Initiate Allergic Sensitization to Peanuts. J Immunol 2020, 204, 3086–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noval Rivas, M.; Burton, O.T.; Oettgen, H.C.; Chatila, T. IL-4 Production by Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells Promotes Food Allergy by Blocking Regulatory T-Cell Function. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2016, 138, 801–811.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.; Miromoto, T.; Beaudin, S.; Salter, B.; Wattie, J.; Howie, K.J.; O’Byrne, P.M.; Gauvreau, G.M.; Sehmi, R. Enumeration of IL-17A/F Producing Innate Lymphoid Cells in Subjects with COPD. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2019, 143, AB218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, T.A.; Broide, D.H. Airway Innate Lymphoid Cells in the Induction and Regulation of Allergy. Allergol Int 2019, 68, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammad, H.; Lambrecht, B.N. The Basic Immunology of Asthma. Cell 2021, 184, 1469–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moro, K.; Yamada, T.; Tanabe, M.; Takeuchi, T.; Ikawa, T.; Kawamoto, H.; Furusawa, J.; Ohtani, M.; Fujii, H.; Koyasu, S. Innate Production of TH2 Cytokines by Adipose Tissue-Associated c-Kit+Sca-1+ Lymphoid Cells. Nature 2010, 463, 540–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neill, D.R.; Wong, S.H.; Bellosi, A.; Flynn, R.J.; Daly, M.; Langford, T.K.A.; Bucks, C.; Kane, C.M.; Fallon, P.G.; Pannell, R.; et al. Nuocytes Represent a New Innate Effector Leukocyte That Mediates Type-2 Immunity. Nature 2010, 464, 1367–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, A.E.; Liang, H.-E.; Sullivan, B.M.; Reinhardt, R.L.; Eisley, C.J.; Erle, D.J.; Locksley, R.M. Systemically Dispersed Innate IL-13–Expressing Cells in Type 2 Immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 11489–11494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christianson, C.A.; Goplen, N.P.; Zafar, I.; Irvin, C.; Good, J.T.; Rollins, D.R.; Gorentla, B.; Liu, W.; Gorska, M.M.; Chu, H.; et al. The Persistence of Asthma Requires Multiple Feedback Circuits Involving ILC2 and IL33. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015, 136, 59–68.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajt, M.L.; Gelhaus, S.L.; Freeman, B.; Uvalle, C.E.; Trudeau, J.B.; Holguin, F.; Wenzel, S.E. Prostaglandin D2 Pathway Upregulation: Relation to Asthma Severity, Control, and TH2 Inflammation. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2013, 131, 1504–1512.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehmi, R.; Smith, S.G.; Kjarsgaard, M.; Radford, K.; Boulet, L.-P.; Lemiere, C.; Prazma, C.M.; Ortega, H.; Martin, J.G.; Nair, P. Role of Local Eosinophilopoietic Processes in the Development of Airway Eosinophilia in Prednisone-Dependent Severe Asthma. Clin Exp Allergy 2016, 46, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, W.W.; Sedgwick, J.B. Eosinophils in Asthma. Ann Allergy 1992, 68, 286–290. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, P.; Martin, J.G.; Cockcroft, D.C.; Dolovich, M.; Lemiere, C.; Boulet, L.-P.; O’Byrne, P.M. Airway Hyperresponsiveness in Asthma: Measurement and Clinical Relevance. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice 2017, 5, 649–659.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, P. What Is an “Eosinophilic Phenotype” of Asthma? Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2013, 132, 81–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hargreave, F.E.; Nair, P. The Definition and Diagnosis of Asthma. Clinical & Experimental Allergy 2009, 39, 1652–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Byrne, P.M.; Inman, M.D.; Parameswaran, K. The Trials and Tribulations of IL-5, Eosinophils, and Allergic Asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2001, 108, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Fang, X.; Zhu, X.; Bai, C.; Zhu, L.; Jin, M.; Wang, X.; Hu, M.; Tang, R.; Chen, Z. IL-13+ Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells Correlate with Asthma Control Status and Treatment Response. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2016, 55, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkler, C.; Hochdörfer, T.; Israelsson, E.; Hasselberg, A.; Cavallin, A.; Thörn, K.; Muthas, D.; Shojaee, S.; Lüer, K.; Müller, M.; et al. Activation of Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells after Allergen Challenge in Asthmatic Patients. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2019, 144, 61–69.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein Wolterink, R.G.J.; Kleinjan, A.; van Nimwegen, M.; Bergen, I.; de Bruijn, M.; Levani, Y.; Hendriks, R.W. Pulmonary Innate Lymphoid Cells Are Major Producers of IL-5 and IL-13 in Murine Models of Allergic Asthma. Eur J Immunol 2012, 42, 1106–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, M.; Liu, S.; Michalec, L.; Sripada, A.; Gorska, M.M.; Alam, R. Experimental Asthma Persists in IL-33 Receptor Knockout Mice Because of the Emergence of Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin–Driven IL-9+ and IL-13+ Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cell Subpopulations. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2018, 142, 793–803.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartemes, K.; Kephart, G.; Fox, S.J.; Kita, H. Enhanced Innate Type 2 Immune Response in Peripheral Blood from Patients with Asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014, 134, 671–678.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.-N.; Tan, W.-P.; Fan, X.-L.; Guo, Y.-B.; Qin, Z.-L.; Li, C.-L.; Chen, D.; Lin, Z.B.; Wen, W.; Fu, Q.-L. Increased Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells Are Correlated with Eosinophilic Granulocytes in Patients with Allergic Airway Inflammation. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2018, 176, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wu, J.; Zhao, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Cao, L.; Liu, Y.; Dong, L. Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells: A Novel Biomarker of Eosinophilic Airway Inflammation in Patients with Mild to Moderate Asthma. Respir Med 2015, 109, 1391–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagakumar, P.; Denney, L.; Fleming, L.; Bush, A.; Lloyd, C.M.; Saglani, S. Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells in Induced Sputum from Children with Severe Asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2016, 137, 624–626.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliphant, C.J.; Barlow, J.L.; McKenzie, A.N.J. Insights into the Initiation of Type 2 Immune Responses. Immunology 2011, 134, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, P.; Surette, M.G.; Virchow, J.C. Neutrophilic Asthma: Misconception or Misnomer? The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 2021, 9, 441–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svenningsen, S.; Nair, P. Asthma Endotypes and an Overview of Targeted Therapy for Asthma. Frontiers in Medicine 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, S.M.; Golebski, K.; Spits, H. Plasticity of Innate Lymphoid Cell Subsets. Nat Rev Immunol 2020, 20, 552–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, T.; Qiu, J.; Ji, Y.; Li, W.; Ding, Z.; Suo, C.; Chang, J.; Wang, J.; He, R.; Qian, Y.; et al. IL-17–Producing ST2+ Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells Play a Pathogenic Role in Lung Inflammation. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2019, 143, 229–244.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernink, J.H.; Ohne, Y.; Teunissen, M.B.M.; Wang, J.; Wu, J.; Krabbendam, L.; Guntermann, C.; Volckmann, R.; Koster, J.; van Tol, S.; et al. C-Kit-Positive ILC2s Exhibit an ILC3-like Signature That May Contribute to IL-17-Mediated Pathologies. Nat Immunol 2019, 20, 992–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golebski, K.; Ros, X.R.; Nagasawa, M.; van Tol, S.; Heesters, B.A.; Aglmous, H.; Kradolfer, C.M.A.; Shikhagaie, M.M.; Seys, S.; Hellings, P.W.; et al. IL-1β, IL-23, and TGF-β Drive Plasticity of Human ILC2s towards IL-17-Producing ILCs in Nasal Inflammation. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-J.; Liu, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, L.-F.; Meng, W.; Zhang, X.; Sun, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, R.-Z.; Yao, C.-F. ILC3-like ILC2 Subset Increases in Minimal Persistent Inflammation after Acute Type II Inflammation of Allergic Rhinitis and Inhibited by Biminkang: Plasticity of ILC2 in Minimal Persistent Inflammation. Journal of Leukocyte Biology 2022, 112, 1445–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Luo, X.; Ma, R.; Tang, Y.; Liu, W. Leptin Promoted IL-17 Production from ILC2s in Allergic Rhinitis. Mediators Inflamm 2020, 2020, 9248479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoni, Y.; Fehlings, M.; Kløverpris, H.N.; McGovern, N.; Koo, S.-L.; Loh, C.Y.; Lim, S.; Kurioka, A.; Fergusson, J.R.; Tang, C.-L.; et al. Human Innate Lymphoid Cell Subsets Possess Tissue-Type Based Heterogeneity in Phenotype and Frequency. Immunity 2017, 46, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernink, J.H.; Krabbendam, L.; Germar, K.; de Jong, E.; Gronke, K.; Kofoed-Nielsen, M.; Munneke, J.M.; Hazenberg, M.D.; Villaudy, J.; Buskens, C.J.; et al. Interleukin-12 and -23 Control Plasticity of CD127+ Group 1 and Group 3 Innate Lymphoid Cells in the Intestinal Lamina Propria. Immunity 2015, 43, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Doty, A.L.; Tang, Y.; Berrie, D.; Iqbal, A.; Tan, S.A.; Clare-Salzler, M.J.; Wallet, S.M.; Glover, S.C. Enrichment of IL-17A+IFN-Γ+ and IL-22+IFN-Γ+ T Cell Subsets Is Associated with Reduction of NKp44+ILC3s in the Terminal Ileum of Crohn’s Disease Patients. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2017, 190, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzurana, L.; Forkel, M.; Rao, A.; Van Acker, A.; Kokkinou, E.; Ichiya, T.; Almer, S.; Höög, C.; Friberg, D.; Mjösberg, J. Suppression of Aiolos and Ikaros Expression by Lenalidomide Reduces Human ILC3-ILC1/NK Cell Transdifferentiation. Eur J Immunol 2019, 49, 1344–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, J.S.; Kearley, J.; Copenhaver, A.M.; Sanden, C.; Mori, M.; Yu, L.; Pritchard, G.H.; Berlin, A.A.; Hunter, C.A.; Bowler, R.; et al. Inflammatory Triggers Associated with Exacerbations of COPD Orchestrate Plasticity of Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells in the Lungs. Nat Immunol 2016, 17, 626–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, S.M.; Bernink, J.H.; Nagasawa, M.; Groot, J.; Shikhagaie, M.M.; Golebski, K.; van Drunen, C.M.; Lutter, R.; Jonkers, R.E.; Hombrink, P.; et al. IL-1β, IL-4 and IL-12 Control the Fate of Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells in Human Airway Inflammation in the Lungs. Nat Immunol 2016, 17, 636–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogasawara, N.; Poposki, J.A.; Klingler, A.I.; Tan, B.K.; Weibman, A.R.; Hulse, K.E.; Stevens, W.W.; Peters, A.T.; Grammer, L.C.; Schleimer, R.P.; et al. IL-10, TGF-β and Glucocorticoid Prevent the Production of Type 2 Cytokines in Human Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018, 141, 1147–1151.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seehus, C.R.; Kadavallore, A.; Torre, B. de la; Yeckes, A.R.; Wang, Y.; Tang, J.; Kaye, J. Alternative Activation Generates IL-10 Producing Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, E.; Lewis, G.; Galle-Treger, L.; Hurrell, B.P.; Helou, D.G.; Shafiei-Jahani, P.; Painter, J.D.; Muench, G.A.; Soroosh, P.; Akbari, O. IL-10 Production by ILC2s Requires Blimp-1 and cMaf, Modulates Cellular Metabolism, and Ameliorates Airway Hyperreactivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021, 147, 1281–1295.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golebski, K.; Layhadi, J.A.; Sahiner, U.; Steveling-Klein, E.H.; Lenormand, M.M.; Li, R.C.Y.; Bal, S.M.; Heesters, B.A.; Vilà-Nadal, G.; Hunewald, O.; et al. Induction of IL-10-Producing Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells by Allergen Immunotherapy Is Associated with Clinical Response. Immunity 2021, 54, 291–307.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Xia, P.; Chen, Y.; Qu, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Ye, B.; Du, Y.; Tian, Y.; Yin, Z.; Xu, Z.; et al. Regulatory Innate Lymphoid Cells Control Innate Intestinal Inflammation. Cell 2017, 171, 201–216.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, K.W.; Vieira, P.; Fiorentino, D.F.; Trounstine, M.L.; Khan, T.A.; Mosmann, T.R. Homology of Cytokine Synthesis Inhibitory Factor (IL-10) to the Epstein-Barr Virus Gene BCRFI. Science 1990, 248, 1230–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, K.W.; de Waal Malefyt, R.; Coffman, R.L.; O’Garra, A. Interleukin-10 and the Interleukin-10 Receptor. Annual Review of Immunology 2001, 19, 683–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, P.J. The Primary Mechanism of the IL-10-Regulated Antiinflammatory Response Is to Selectively Inhibit Transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005, 102, 8686–8691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, S.S.; Cheng, G. Role of Interleukin 10 Transcriptional Regulation in Inflammation and Autoimmune Disease. Crit Rev Immunol 2012, 32, 23–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glocker, E.-O.; Kotlarz, D.; Klein, C.; Shah, N.; Grimbacher, B. IL-10 and IL-10 Receptor Defects in Humans. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2011, 1246, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentino, D.F.; Bond, M.W.; Mosmann, T.R. Two Types of Mouse T Helper Cell. IV. Th2 Clones Secrete a Factor That Inhibits Cytokine Production by Th1 Clones. J Exp Med 1989, 170, 2081–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallrapp, A.; Riesenfeld, S.J.; Burkett, P.R.; Abdulnour, R.-E.E.; Nyman, J.; Dionne, D.; Hofree, M.; Cuoco, M.S.; Rodman, C.; Farouq, D.; et al. The Neuropeptide NMU Amplifies ILC2-Driven Allergic Lung Inflammation. Nature 2017, 549, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wong, K.; Ouyang, W.; Rutz, S. Targeting IL-10 Family Cytokines for the Treatment of Human Diseases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2019, 11, a028548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, M.; Vieira, P.; O’Garra, A. Biology and Therapeutic Potential of Interleukin-10. J Exp Med 2019, 217, e20190418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hori, S.; Nomura, T.; Sakaguchi, S. Control of Regulatory T Cell Development by the Transcription Factor Foxp3. Science 2003, 299, 1057–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamoto, C.; Kojo, S.; Yamashita, M.; Moro, K.; Lacaud, G.; Shiroguchi, K.; Taniuchi, I.; Ebihara, T. Runx/Cbfβ Complexes Protect Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells from Exhausted-like Hyporesponsiveness during Allergic Airway Inflammation. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonpiyathad, T.; Tantilipikorn, P.; Ruxrungtham, K.; Pradubpongsa, P.; Mitthamsiri, W.; Piedvache, A.; Thantiworasit, P.; Sirivichayakul, S.; Jacquet, A.; Suratannon, N.; et al. IL-10-Producing Innate Lymphoid Cells Increased in Patients with House Dust Mite Allergic Rhinitis Following Immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021, 147, 1507–1510.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, H.; Arae, K.; Unno, H.; Miyauchi, K.; Toyama, S.; Nambu, A.; Oboki, K.; Ohno, T.; Motomura, K.; Matsuda, A.; et al. An Interleukin-33-Mast Cell-Interleukin-2 Axis Suppresses Papain-Induced Allergic Inflammation by Promoting Regulatory T Cell Numbers. Immunity 2015, 43, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.C.F.; Szeto, A.C.H.; Heycock, M.W.D.; Clark, P.A.; Walker, J.A.; Crisp, A.; Barlow, J.L.; Kitching, S.; Lim, A.; Gogoi, M.; et al. RORα Is a Critical Checkpoint for T Cell and ILC2 Commitment in the Embryonic Thymus. Nat Immunol 2021, 22, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, A.; Krishnamoorthy, N.; Oriss, T.B.; Fei, M.; Ray, P.; Ray, A. Inhaled Antigen Upregulates Retinaldehyde Dehydrogenase In Lung CD103+ But Not Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells To Induce Foxp3 De Novo in CD4+ T Cells and Promote Airway Tolerance. J Immunol 2013, 191, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baban, B.; Braun, M.; Khodadadi, H.; Ward, A.; Alverson, K.; Malik, A.; Nguyen, K.; Nazarian, S.; Hess, D.C.; Forseen, S.; et al. AMPK Induces Regulatory Innate Lymphoid Cells after Traumatic Brain Injury. JCI Insight 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coomes, S.M.; Kannan, Y.; Pelly, V.S.; Entwistle, L.J.; Guidi, R.; Perez-Lloret, J.; Nikolov, N.; Müller, W.; Wilson, M.S. CD4+ Th2 Cells Are Directly Regulated by IL-10 during Allergic Airway Inflammation. Mucosal Immunol 2017, 10, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelly, V.S.; Kannan, Y.; Coomes, S.M.; Entwistle, L.J.; Rückerl, D.; Seddon, B.; MacDonald, A.S.; McKenzie, A.; Wilson, M.S. IL-4-Producing ILC2s Are Required for the Differentiation of TH2 Cells Following Heligmosomoides Polygyrus Infection. Mucosal Immunology 2016, 9, 1407–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.E.; Hassan, M.; Burton, B.R.; Britton, G.; Hill, E.V.; Verhagen, J.; Wraith, D.C. IL-4 Enhances IL-10 Production in Th1 Cells: Implications for Th1 and Th2 Regulation. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 11315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, B.; Buttrick, T.; Bassil, R.; Zhu, C.; Olah, M.; Wu, C.; Xiao, S.; Orent, W.; Elyaman, W.; Khoury, S.J. IL-4 and Retinoic Acid Synergistically Induce Regulatory Dendritic Cells Expressing Aldh1a2. J Immunol 2013, 191, 3139–3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meylan, F.; Hawley, E.T.; Barron, L.; Barlow, J.L.; Penumetcha, P.; Pelletier, M.; Sciumè, G.; Richard, A.C.; Hayes, E.T.; Gomez-Rodriguez, J.; et al. The TNF-Family Cytokine TL1A Promotes Allergic Immunopathology through Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells. Mucosal Immunol 2014, 7, 958–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machida, K.; Aw, M.; Salter, B.M.A.; Ju, X.; Mukherjee, M.; Gauvreau, G.M.; O’Byrne, P.M.; Nair, P.; Sehmi, R. The Role of the TL1A/DR3 Axis in the Activation of Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells in Subjects with Eosinophilic Asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020, 202, 1105–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, A.-H.; Xiao, Q.; Liu, G.-Y.; Shi, K.; Yang, Q.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.-F.; Wang, H.-K.; Cai, W.-P.; Guan, Y.-J.; et al. ICAM-1 Controls Development and Function of ILC2. J Exp Med 2018, 215, 2157–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, P.; Allard, B.; Manicki, P.; Jolivel, V.; Levionnois, E.; Jeljeli, M.; Henrot, P.; Izotte, J.; Leleu, D.; Groppi, A.; et al. TGFβ Promotes Low IL10-Producing ILC2 with Profibrotic Ability Involved in Skin Fibrosis in Systemic Sclerosis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2021, 80, 1594–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Kuroki, K.; Ohki, I.; Sasaki, K.; Kajikawa, M.; Maruyama, T.; Ito, M.; Kameda, Y.; Ikura, M.; Yamamoto, K.; et al. Molecular Basis for E-Cadherin Recognition by Killer Cell Lectin-like Receptor G1 (KLRG1). J Biol Chem 2009, 284, 27327–27335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henson, S.M.; Akbar, A.N. KLRG1--More than a Marker for T Cell Senescence. Age (Dordr) 2009, 31, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffont, S.; Blanquart, E.; Savignac, M.; Cénac, C.; Laverny, G.; Metzger, D.; Girard, J.-P.; Belz, G.T.; Pelletier, L.; Seillet, C.; et al. Androgen Signaling Negatively Controls Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2017, 214, 1581–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loering, S.; Cameron, G.J.; Bhatt, N.P.; Belz, G.T.; Foster, P.S.; Hansbro, P.M.; Starkey, M.R. Differences in Pulmonary Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells Are Dependent on Mouse Age, Sex and Strain. Immunol Cell Biol 2021, 99, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Moarbes, V.; Gaudreault, V.; Shan, J.; Aldossary, H.; Cyr, L.; Fixman, E.D. Sex Differences in IL-33-Induced STAT6-Dependent Type 2 Airway Inflammation. Frontiers in Immunology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadel, S.; Ainsua-Enrich, E.; Hatipoglu, I.; Turner, S.; Singh, S.; Khan, S.; Kovats, S. A Major Population of Functional KLRG1- ILC2s in Female Lungs Contributes to a Sex Bias in ILC2 Numbers. Immunohorizons 2018, 2, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cephus, J.; Stier, M.; Fuseini, H.; Yung, J.; Toki, S.; Bloodworth, M.; Zhou, W.; Goleniewska, K.; Zhang, J.; Garon, S.; et al. Testosterone Attenuates Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cell-Mediated Airway Inflammation. Cell Rep 2017, 21, 2487–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurrell, B.P.; Howard, E.; Galle-Treger, L.; Helou, D.G.; Shafiei-Jahani, P.; Painter, J.D.; Akbari, O. Distinct Roles of LFA-1 and ICAM-1 on ILC2s Control Lung Infiltration, Effector Functions, and Development of Airway Hyperreactivity. Frontiers in Immunology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, V.; Chesné, J.; Ribeiro, H.; García-Cassani, B.; Carvalho, T.; Bouchery, T.; Shah, K.; Barbosa-Morais, N.L.; Harris, N.; Veiga-Fernandes, H. Neuronal Regulation of Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells via Neuromedin U. Nature 2017, 549, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, M.; Nakanishi, Y.; Motomura, Y.; Takamatsu, H.; Koyama, S.; Nishide, M.; Naito, Y.; Izumi, M.; Mizuno, Y.; Yamaguchi, Y.; et al. Semaphorin 6D–Expressing Mesenchymal Cells Regulate IL-10 Production by ILC2s in the Lung. Life Sci. Alliance 2022, 5, e202201486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, C.; Heinrich, F.; Neumann, K.; Junghans, V.; Mashreghi, M.-F.; Ahlers, J.; Janke, M.; Rudolph, C.; Mockel-Tenbrinck, N.; Kühl, A.A.; et al. Role of Blimp-1 in Programing Th Effector Cells into IL-10 Producers. J Exp Med 2014, 211, 1807–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Dodd, H.; Moser, E.K.; Sharma, R.; Braciale, T.J. CD4+ T Cell Help and Innate-Derived IL-27 Induce Blimp-1-Dependent IL-10 Production by Antiviral CTLs. Nat Immunol 2011, 12, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Pokrovskii, M.; Ding, Y.; Yi, R.; Au, C.; Harrison, O.J.; Galan, C.; Belkaid, Y.; Bonneau, R.; Littman, D.R. C-MAF-Dependent Regulatory T Cells Mediate Immunological Tolerance to a Gut Pathobiont. Nature 2018, 554, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutz, S.; Ouyang, W. Regulation of Interleukin-10 Expression. In Regulation of Cytokine Gene Expression in Immunity and Diseases; Ma, X., Ed.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2016; pp. 89–116. ISBN 978-94-024-0921-5. [Google Scholar]

- Morita, H.; Kubo, T.; Rückert, B.; Ravindran, A.; Soyka, M.B.; Rinaldi, A.O.; Sugita, K.; Wawrzyniak, M.; Wawrzyniak, P.; Motomura, K.; et al. Induction of Human Regulatory Innate Lymphoid Cells from Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells by Retinoic Acid. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019, 143, 2190–2201.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).