Submitted:

17 September 2023

Posted:

19 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Spores are the main dispersal mode of fungi [27]. Forest patches in urban environments receive reduced numbers of migrating fungal spores, which could result in decreased fungal diversity and altered composition of the soil fungal community [20]. We therefore hypothesize that the species richness of fungi in the soil decreases with increasing degree of urbanization and that increasing urbanization leads to changes in the composition of soil fungi.

- (2)

- The different fungal phyla differ in their susceptibility to changes in biotic and abiotic characteristics of temperate forests [28,29]. Urbanization can change vegetation characteristics and soil properties [30]. We therefore hypothesize that urbanization-induced changes in forest characteristics will affect the different fungal phyla in different ways.

- (3)

- Symbiotrophic fungi are sensitive to disturbances [31]. This may result in a lower abundance and/or species richness of symbiotrophic soil fungi in urban than in rural habitats [32,33]. Based on these findings, we hypothesize that the abundance of symbiotrophic fungi decreases with increasing degree of urbanization.

2. Materials and Methods

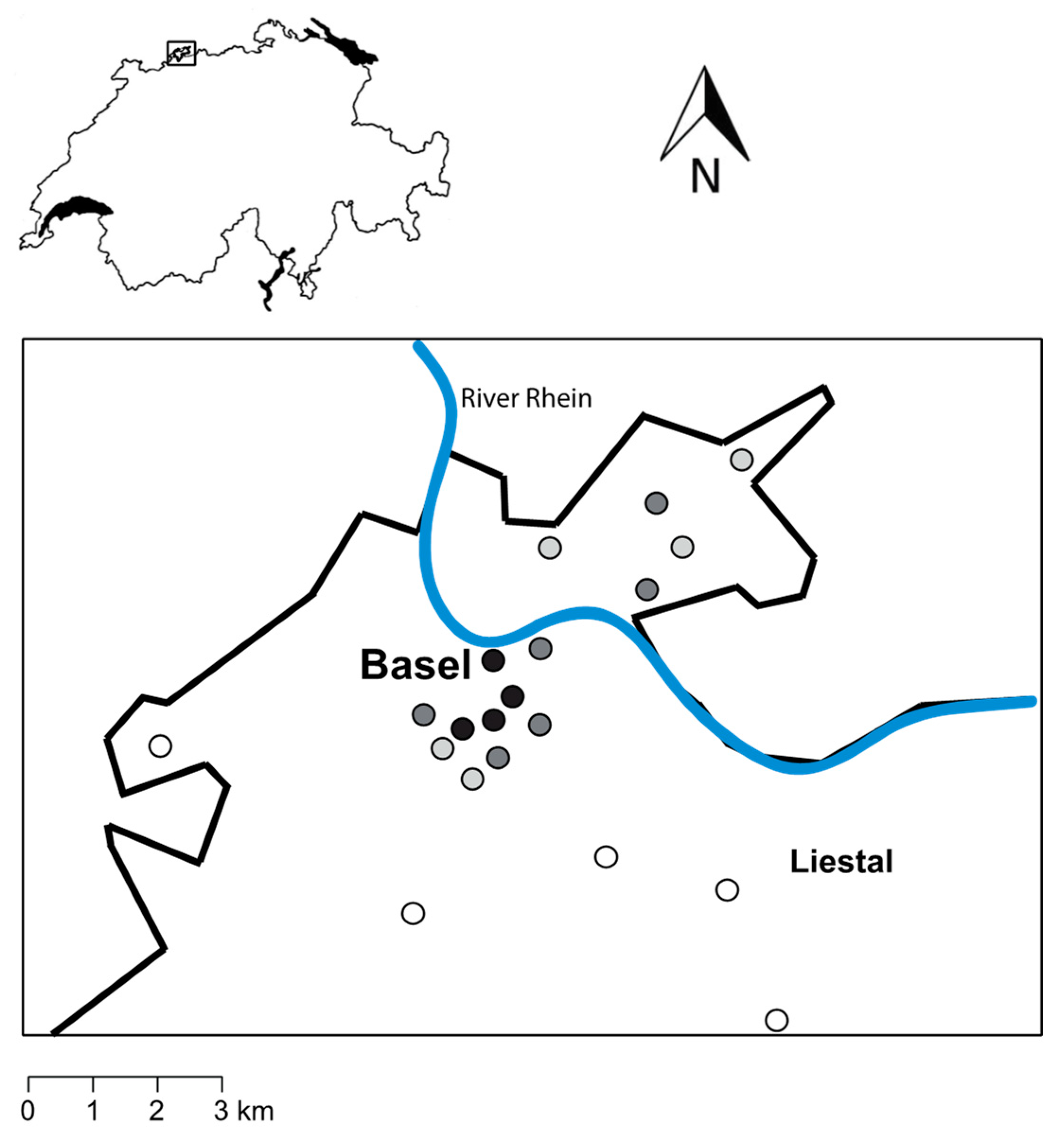

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Design of the Field Survey

2.3. Forest Vegetation Survey

2.4. Soil Sampling and Physiochemical Properties

2.5. Soil Fungal Community

2.6. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Vegetation Characteristics and Soil Properties

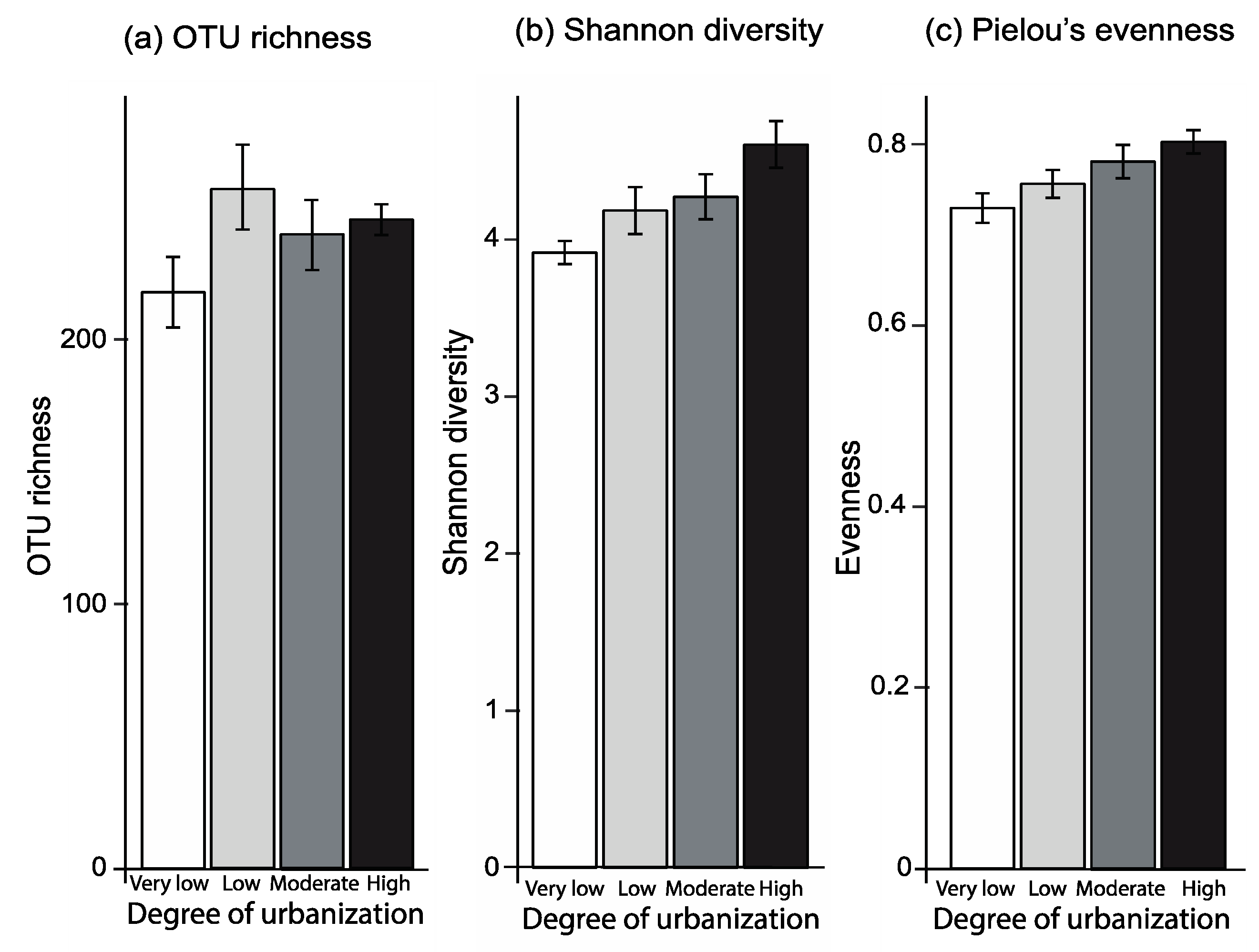

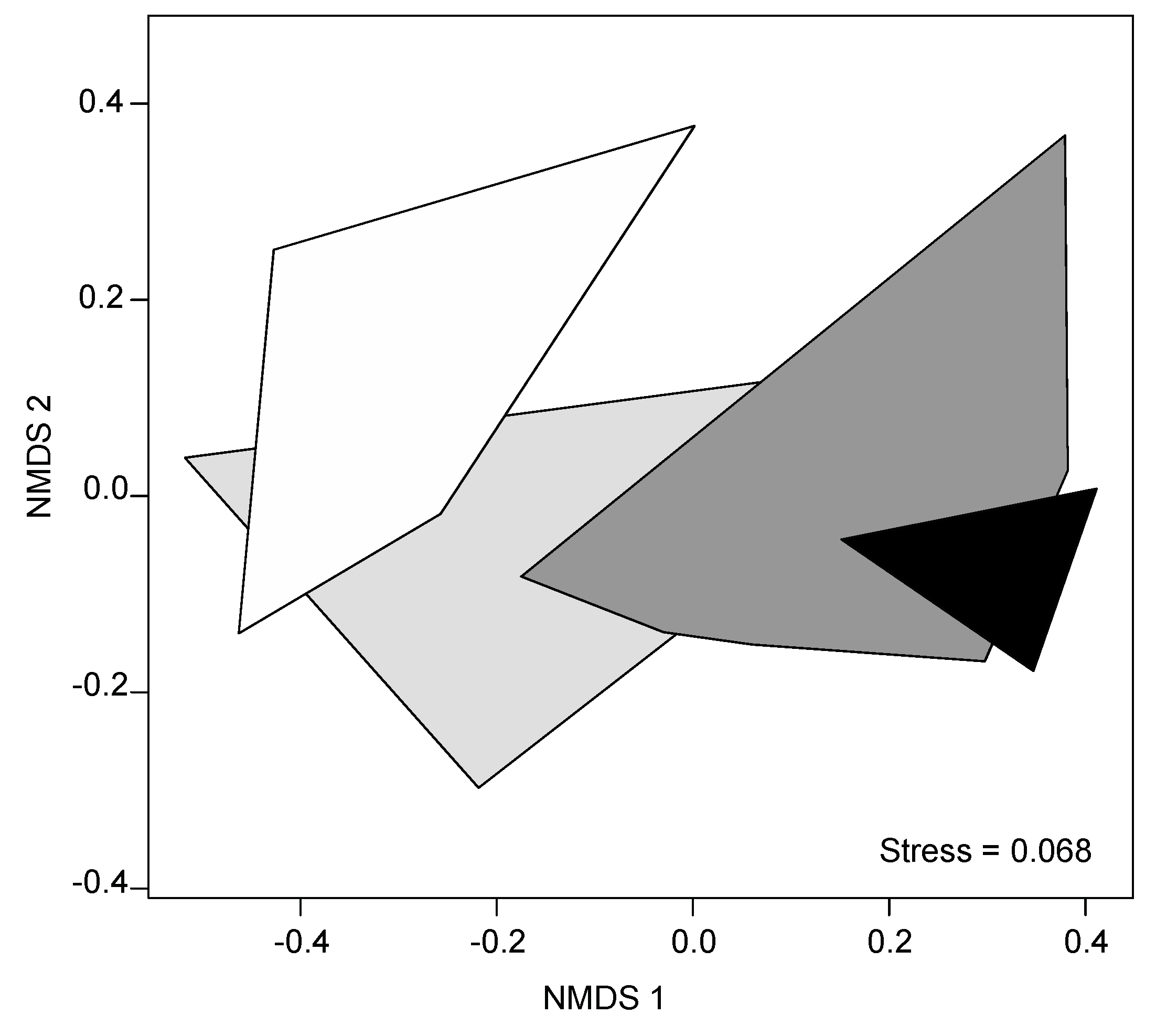

3.2. Diversity and Composition of Fungal OTUs

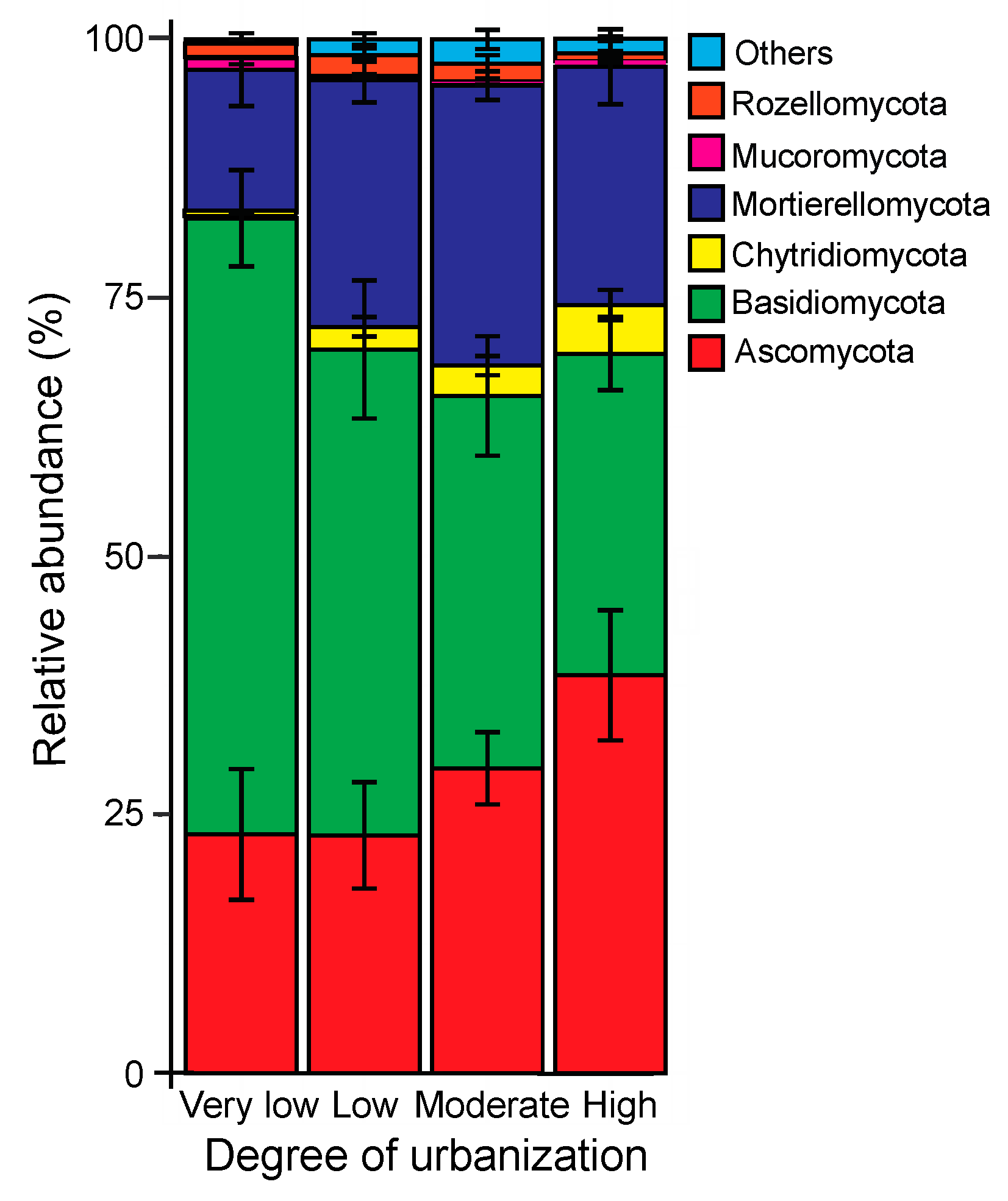

3.3. Soil Fungal Community

3.4. Soil Fungal Functional Composition

4. Discussion

4.1. Diversity and Composition of Fungal OTUs

4.2. Soil Fungal Community

4.3. Soil Fungal Functional Composition

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grimm, N.B.; Faeth, S.H.; Golubiewski, N.E.; Redman, C.L.; Wu, J.G.; Bai, X.M.; Briggs, J.M. Global change and the ecology of cities. Science 2008, 319, 756–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvejić, R.; Eler, K.; Pintar, M.; Železnikar, Š.; Haase, D.; Kabisch, N.; Strohbach, M. A typology of urban green spaces, ecosystem services provisioning services and demands. 2015, Report D3.1, European Union, Brüssel.

- Dwyer, J.F.; McPherson, E.G.; Schroeder, H.W. , Rowntree, R. Assessing the benefits and costs of the urban forest. Arboric. J. 1992, 18, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grammatikopoulou, I.; Vackarova, D. The value of forest ecosystem services: A meta-analysis at the European scale and application to national ecosystem accounting. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, S.T.A.; Cadenasso, M.L.; Grove, J.M.; Boone, C.G.; Groffman, P.M.; Irwin, E.; Kaushal, S.S.; Marshall, V.; McGrath, B.P.; Nilon, C.H.; et al. Urban ecological systems: Scientific foundations and a decade of progress. J. Environ. Manage. 2011, 92, 331–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melliger, R.L.; Braschler, B.; Rusterholz, H.P.; Baur, B. Diverse effects of degree of urbanisation and forest size on species richness and functional diversity of plants, and ground surface-active ants and spiders. Plos One 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenoglio, M.S.; Rossetti, M.R.; Videla, M. Negative effects of urbanization on terrestrial arthropod communities: A meta-analysis. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2020, 29, 1412–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.; Rusterholz, H.P.; Baur, B. Saproxylic insects and fungi in deciduous forests along a rural–urban gradient. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 11, 1634–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, D.U.; Vitousek, P.M. The effects of plant composition and diversity on ecosystem processes. Science 1997, 277, 1302–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin III, F.S.; Zavaleta, E.S.; Eviner, V.T.; Naylor, R.L.; Vitousek, P.M.; Reynolds, H.L.; Hooper, D.U.; Lavorel, S.; Sala, O.E.; Hobbie, S.E.; et al. Consequences of changing biodiversity. Nature 2000, 405, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decon, J.W. Fungal Biology, 4nd ed.; John Willey & Sons: New York, 2005; p. 384. [Google Scholar]

- Bardgett, R.D.; van der Putten, W.H. Belowground biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Nature 2014, 515, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treseder, K.K.; Lennon, J.T. Fungal traits that drive ecosystem dynamics on land. Microb. Molec. Biol. Rev. 2015, 79, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldrian, P. Forest microbiome: diversity, complexity and dynamics. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2017, 41, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, N.H.; Song, Z. W.; Bates, S.T.; Branco, S.; Tedersoo, L.; Menke, J.; Schilling, J.S.; Kennedy, P.G. FUNGuild: An open annotation tool for parsing fungal community datasets by ecological guild. Fungal Ecol. 2016, 20, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadowaki, K.; Yamamoto, S.; Sato, H.; Tanabe, A.S.; Hidaka, A.; Toju, H. Mycorrhizal fungi mediate the direction and strength of plant-soil feedbacks differently between arbuscular mycorrhizal and ectomycorrhizal communities. Community Biol. 2018, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomdola, D.; Bhunjun, C.S.; Hyde, K.D.; Jeewon, R.; Pem, D.; Jayawardena, R.S. Ten important forest fungal pathogens: a review on their emergence and biology. Mycosphere 2022, 13, 612–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terhonen, E.; Kovalchuk, A.; Zarsav, A.; Asiegbu, F.O. Biocontrol potential of forest tree endophytes. In Endophytes of Forest Trees: Biology and Applications, 2nd Edition; Pirttilä, M.A., Frank, Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 283–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, A.; Crawley, W. Pathogens and the structure of plant-communities. TREE 1994, 9, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrego, N.; Crosier, B.; Somervuo, P.; Ivanova, N.; Abrahamyan, A.; Abdi, A.; Hamalainen, K.; Junninen, K.; Maunula, M.; Purhonen, J.; et al. Fungal communities decline with urbanization – more in air than in soil. ISME J. 2020, 14, 2806–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.J.; Martinez, A.; Cleavenger, S.; Rudolph, J.; Barberan, A. Changes in soil microbial communities across an urbanization gradient: a local-scale temporal study in the arid Southwestern USA. Microorganisms 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Barberan, A.; Gao, C.; Zhang, Z.C.; Wang, M.; Wurzburger, N.; Wang, X.; Zhang, R.; Li, J.X.; Zhang, J. Impact of urbanization on soil microbial diversity and composition in the megacity of Shanghai. Land Degrad. Dev. 2022, 33, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, J.; Roy, J.; Hempel, S.; Rillig, M.C. Soil microbial communities shift along an urban gradient in Berlin, Germany. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.L.; Kan, L.; Su, Z.Y.; Liu, X.D.; Zhang, L. The Composition and diversity of soil bacterial and fungal communities along an urban-to-rural gradient in South China. Forests 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Yu, S.Q.; Chen, X.H.; Liu, X.D.; Zeng, H.X.; Wu, W.K.; Liu, M.Y.; Su, C.H.; Xu, G.L. Soil microbial community changes in response to the environmental gradients of urbanization in Guangzhou City. Urban Ecosyst. 2022, 25, 1865–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindahl, B.D.; Nilsson, R.H.; Tedersoo, L.; Abarenkov, K.; Carlsen, T.; Kjoller, R.; Koljalg, U.; Pennanen, T.; Rosendahl, S.; Stenlid, J.; et al. Fungal community analysis by high-throughput sequencing of amplified markers – a user's guide. New Phytol. 2013, 199, 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, V.B.; Aguilar-Trigueros, C.A.; Mansour, I.; Rillig, M.C. Fungal dispersal across spatial scales. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2022, 53, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osburn, E.D.; McBride, S.G.; Aylward, F.O.; Badgley, B.D.; Strahm, B.D.; Knoepp, J.D.; Barrett, J.E. Soil bacterial and fungal communities exhibit distinct long-term responses to disturbance in temperate forests. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odriozola, I.; Martinovic, T.; Bahnmann, B.D.; Rysanek, D.; Masinova, T.; Sedlak, P.; Merunkova, K.; Kohout, P.; Tomsovsky, M.; Baldrian, P. Stand age affects fungal community composition in a Central European temperate forest. Fungal Ecol. 2020, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enescu, R.E.; Dinca, L.; Zup, M.; Davidescu, S.; Vasile, D. Assessment of soil physical and chemical properties among urban and peri-urban forests: a case study from metropolitan area of Brasov. Forests 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Heyde, M.; Ohsowski, B.; Abbott, L.K.; Hart, M. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus responses to disturbance are context-dependent. Mycorrhiza 2017, 27, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, D.J.E.; Pouyat, R.; Szlavecz, K.; Setälä, H.; Kotze, D. J.; Yesilonis, I.; Cilliers, S.; Hornung, E.; Dombos, M.; Yarwood, S.A. Urbanization erodes ectomycorrhizal fungal diversity and may cause microbial communities to converge. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.Y.; Yang, B.S.; Wang, H.; Sun, W.; Jiao, K.Q.; Qin, G.H. Changes in soil ectomycorrhizal fungi community in oak forests along the urban-rural gradient. Forests 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arealstatistik Schweiz 2021. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/raum-umwelt/erhebungen/area.html (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Statistischer Atlas der Schweiz 2021. Available online: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/regionalstatistik/atlanten/statistischer-atlas-schweiz.html (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- MeteoSwiss, 2023. Climate Normals 1981–2010. Federal Office of Meteorology and Climatology MeteoSwiss. Available online: www.meteoswiss.admin.ch (accessed on 30 April 2023).

- Burnand, J.; Hasspacher, B. Waldstandorte beider Basel. Quellen und Forschungen zur Geschichte und Landeskunde des Kanton Basel-Landschaft, 2nd ed.; Verlag des Kantons Basel-Landschaft: Liestal, Switzerland, 1999; p. 266. [Google Scholar]

- Google Earth. Available online: https://www.google.com/intl/de/earth (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- Mueller-Dombois, D.; Ellenberg, H. Aims and Methods of Vegetation Ecology; Blackburn Press: Caldwell, NJ, USA, 2002.; p. 547. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, S.E. Chemical Analysis of Ecological Materials, 2nd ed.; Blackwell Scientific: Oxford, U.K, 1989; p. 368. [Google Scholar]

- Bremner, J.; Mulvaney, C. Total nitrogen. In Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 2. Chemical and Microbiological Methods; Page, A.L., Ed.; American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 1982; pp. 595–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, D.L.; Page, A.L.; Helmke, P.A.; Loeppert, R.H.; Soltanpour, P.N.; Tabatabai, M.A.; Johnston, C.T.; Sumner, M.E. Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 3, Chemical Methods, 3rd ed.; ASA: Madison, Wisconsin, USA, 1996, p. 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J. ; Bruns,T.; Lee, S., Taylor, J.W. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications. Innis, M.A., Gelfan, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press Inc.: New York, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 2460–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, R.C. UPARSE: Highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 996–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, R.C.; Haas, B.J.; Clemente, J.C.; Quince, C.; Knight, R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2194–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Garrity, G.M.; Tiedje, J.M.; Cole, J.R. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 7, 5261–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, R.H.; Larsson, K.H.; Taylor, A.F.S.; Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Jeppesen, T.S.; Schigel, D.; Kennedy, P.; Picard, K.; Glöckner, F.O.; Tedersoo, L.; et al. The UNITE database for molecular identification of fungi: handling dark taxa and parallel taxonomic classifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayers, E.W.; Bolton, E.E.; Brister, J.R.; Canese, K.; Chan, J.; Comeau, D.C.; Connor, R.; Funk, K.; Kelly, C.; Kim, S.; et al. Database resources of the national center for biotechnology information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D20–D26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team, 2020. R: a language and environment for statistical computing, Version 3.6.3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna. https://www.R-project.org/.

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Simpson, G.L.; Solymos, R.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Wagner, H. Vegan community ecology package. R package version 2.0–10. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Anderson, M.J. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol. 2001, 26, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cáceres, M.; Legendre, P. Associations between species and groups of sites: indices and statistical inference. Ecology 2009, 90, 3566–3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.R. Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure". Austral Ecology. 1993, 18, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldmann, K.; Schröter, K.; Pena, R.; Schöning, I.; Schrumpf, M.; Buscot, F.; Polle, A.; Wubet, T. Divergent habitat filtering of root and soil fungal communities in temperate beech forests. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahnmann, B.; Masinova, T.; Halvorsen, R.; Davey, M.L.; Sedlak, P.; Tomsovsky, M.; Baldrian, P. Effects of oak, beech and spruce on the distribution and community structure of fungi in litter and soils across a temperate forest. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 119, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asplund, J.; Kauserud, H.; Ohlson, M.; Nybakken, L. Spruce and beech as local determinants of forest fungal community structure in litter, humus and mineral soil. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2019, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clausing, S.; Likulunga, L.E.; Janz, D.; Feng, H.Y.; Schneider, D.; Daniel, R.; Kruger, J.; Lang, F.; Polle, A. Impact of nitrogen and phosphorus addition on resident soil and root mycobiomes in beech forests. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2021, 57, 1031–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorfer, M.; Mayer, M.; Berger, H.; Rewald, B.; Tallian, C.; Matthews, B.; Sanden, H.; Katzensteiner, K.; Godbold, D.L. High fungal diversity but low seasonal dynamics and ectomycorrhizal abundance in a mountain beech forest. Microb. Ecol. 2021, 82, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likulunga, L.E.; Perez, C.A.R.; Schneider, D.; Daniel, R.; Polle, A. Tree species composition and soil properties in pure and mixed beech-conifer stands drive soil fungal communities. For. Ecol. Manage. 2021, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholier, T.; Lavrinienko, A.; Brila, I.; Tukalenko, E.; Hindstrom, R.; Vasylenko, A.; Cayol, C.; Ecke, F.; Singh, N.J.; Forsman, J.T.; et al. Urban forest soils harbour distinct and more diverse communities of bacteria and fungi compared to less disturbed forest soils. Molecular Ecology 2023, 32, 504–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo, L.; Anslan, S.; Bahram, M.; Drenkhan, R.; Pritsch, K.; Buegger, F.; Padari, A.; Hagh-Doust, N.; Mikryukov, V.; Gohar, D.; et al. Regional-scale in-depth analysis of soil fungal diversity reveals strong pH and plant species effects in Northern Europe. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christel, A.; Dequiedt, S.; Chemidlin-Prevost-Bouré, N.; Mercier, F.; Tripied, J.; Comment, G.; Djemiel, C.; Bargeot, L.; Matagne, E.; Fougeron, A.; et al. Urban land uses shape soil microbial abundance and diversity. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Heijden, M.G.A.; Klironomos, J.N.; Ursic, M.; Moutoglis, P.; Streitwolf-Engel, R.; Boller, T.; Wiemken, A.; Sanders, I.R. Mycorrhizal fungal diversity determines plant biodiversity, ecosystem variability and productivity. Nature 1998, 396, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo, L.; Bahram, M.; Cajthaml, T.; Polme, S.; Hiiesalu, I.; Anslan, S.; Harend, H.; Buegger, F.; Pritsch, K.; Koricheva, J.; et al. Tree diversity and species identity effects on soil fungi, protists and animals are context dependent. ISME J. 2016, 10, 346–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wubet, T.; Christ, S.; Schoning, I.; Boch, S.; Gawlich, M.; Schnabel, B.; Fischer, M.; Buscot, F. Differences in soil fungal communities between European Beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) dominated forests are related to soil and understory vegetation. Plos One 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kameshwar, A.K.S.; Qin, W.S. Systematic review of publicly available non-Dikarya fungal proteomes for understanding their plant biomass-degrading and bioremediation potentials. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, M. The Fungi: 1, 2, 3… 5.1 million species? Am. J. Bot. 2011, 98, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nacke, H.; Goldmann, K.; Schoning, I.; Pfeiffer, B.; Kaiser, K.; Castillo-Villamizar, G.A.; Schrumpf, M.; Buscot, F.; Daniel, R.; Wubetz, T. Fine spatial scale variation of soil microbial communities under European Beech and Norway Spruce. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.J.; Kuang, J.L.; Wang, P.D.; Shu, W.S.; Barberan, A. Associations between human impacts and forest soil microbial communities. Elementa 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leake, J.R.; Johnson, D.; Donnelly, D.P.; Muckle, G.E.; Boddy, L.; Read, D.J. Networks of power and influence: the role of mycorrhizal mycelium in controlling plant communities and agroecosystem functioning. Can. J. Bot. 2004, 82, 1016–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindahl, B.; Stenlid, J.; Finlay, R. Effects of resource availability on mycelial interactions and P-32 transfer between a saprotrophic and an ectomycorrhizal fungus in soil microcosms. FEMS Microb. Ecol. 2001, 38, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bödeker, I.T.M.; Lindahl, B.D.; Olson, Å.; Clemmensen, K.E. Mycorrhizal and saprotrophic fungal guilds compete for the same organic substrates but affect decomposition differently. Funct. Ecol. 2016, 30, 1967–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, D.H. Ectomycorrhizae as biological deterrents to pathogenic root infections. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1972, 10, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.; Yang, J.R.; Wu, Y.G.; Zhang, W.H.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.J.; Xing, H.; Liu, Y. Correlation between fine root traits and pathogen richness depends on plant mycorrhizal types. Oikos 2023, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Urban Agenda 2016. URL: http://habitat3.org/the-new-urban-agenda (accessed on 18 August 2023).

| Forest | Coordinates | Historical development1 |

Forest vegetation2 | Elevation (m a.s.l.) | Exposure3 | % cover of sealed area (r = 500 m) |

Degree of urbanization4 | Forest area (ha) | % cover of forest (r = 500 m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BS1 | 47° 33' 13" N 7° 36' 17" E |

Planted | Galio-Fagetum Pulmonarietosum | 363 | WNW | 59 | 4 | 0.33 |

2 |

| BS2 | 47° 33' 14" N 7° 36' 49" E |

Fragment | Galio Odorati-Fagetum Cornetosum | 262 | NE | 39 | 3 | 1.42 | 3 |

| BS3 | 47° 33' 55" N 7° 38' 41" E |

Planted | Galio Odorati-Fagetum Pulmonarietosum | 319 | NNW | 30 | 3 | 0.41 | 56 |

| BS4 | 47° 32' 12" N 7° 36' 6" E |

Fragment | Galio Odorati-Fagetum Cornetosum | 321 | NE | 54 | 4 | 1.16 | 13 |

| BS5 | 47° 32' 04.6" N 7° 31' 16.2" E |

Forest | Galio-Fagetum Pulmonarietosum | 351 | – | 1 | 1 | 76.2 | 45 |

| BS6 | 47° 34' 53" N 7° 38' 52" E |

Planted | Galio Odorati-Fagetum | 283 | – | 33 | 3 | 0.33 | 1 |

| BS7 | 47° 32' 18" N 7° 35' 39" E |

Planted | Aro-Fagetum | 325 | NE | 43 | 3 | 0.23 | 6 |

| BS8 | 47° 31' 49" N 7° 35' 49" E |

Fragment | Galio Odorati-Fagetum Typicum | 370 | E | 23 | 2 | 2.70 | 11 |

| BS9 | 47° 31' 55 N 7° 36' 6" E |

Fragment | Galio Odorati-Fagetum Typicum | 338 | NW | 44 | 3 | 2.10 | 19 |

| BS10 | 47° 34' 20" N 7° 37' 6" E |

Forest | Galio-Carpinetum Corydalidetosum | 269 | – | 25 | 2 | 2.53 | 35 |

| BS11 | 47° 29' 11" N 7° 40' 43" E |

Forest | Galio-Fagetum Pulmonarietosum | 565 | – | 3 | 1 | 186.4 | 92 |

| BS12 | 47° 34' 29" N 7° 39' 58" E |

Forest | Galio Odorati-Fagetum Cornetosum | 450 | NW | 10 | 2 | 5.15 | 37 |

| BS13 | 47° 35' 18” N 7° 40' 20” E |

Forest | Galio Odorati-Fagetum Cornetosum | 473 | SW | 13 | 2 | 3.42 | 54 |

| BS14 | 47° 32' 31" N 7° 35' 2" E |

Fragment | Galio Odorati-Fagetum Cornetosum | 299 | NNE | 35 | 3 | 1.95 | 6 |

| BS15 | 47° 30' 53" N 7° 38' 11" E |

Forest | Galio-Fagetum Pulmonarietosum | 418 | – | 2 | 1 | 79.0 | 43 |

| BS16 | 47° 30' 31" N 7° 40' 04" E |

Forest | Aro-Fagetum | 454 | – | 1 | 1 | 337.0 | 66 |

| BS17 | 47° 32' 43" N 7° 36' 27" E |

Planted | Aro-Fagetum | 276 | – | 69 | 4 | 0.37 | 2 |

| BS18 | 47° 30' 18" N 7° 34' 46" E |

Forest | Galio Odorati-Fagetum Typicum | 380 | – | 2 | 1 | 237.7 | 59 |

| BS19 | 47° 34' 23" N 7° 39' 16" E |

Planted | Galio Odorati-Fagetum Typicum | 380 | – | 9 | 2 | 1.28 | 38 |

| BS20 | 47° 32' 14" N 7° 35' 26" E |

Fragment | Galio Odorati-Fagetum Cornetosum | 326 | E | 56 | 4 | 0.89 | 5 |

| Degree of urbanization | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Very low (rural) (n = 5) |

Low (n = 5) |

Moderate (n = 6) |

High (n = 4) |

p | |

| Forest vegetation characteristics | |||||

| Ground vegetation cover (%) | 67.2 ± 9.5 | 56.2 ± 11.7 | 78.0 ± 18.1 | 73.9 ± 15.9 | N.S. |

| Plant species richness1 | 9.5 ± 1.4a | 6.8 ± 0.6a | 5.6 ± 0.4b | 5.2 ± 0.2b | 0.005 |

| Shrub species richness2 | 4.0 ± 0.7a | 4.0 ± 0.9a | 6.0 ± 0.8b | 7.5 ± 0.3b | 0.034 |

| Tree species richness2 | 3.8 ± 0.6 | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 3.8 ± 0.6 | 2.5 ± 0.8 | N.S. |

| Soil properties | |||||

| Soil moisture (%) | 31.4 ± 2.3 | 29.0 ± 1.5 | 28.8 ± 1.6 | 25.7 ± 2.1 | N.S. |

| Soil pH | 5.6 ± 0.4a | 5.7 ± 0.4a | 6.6 ± 0.2b | 7.2 ± 0.1b | 0.004 |

| SOM (%) | 18.3 ± 6.9 | 12.7 ± 1.9 | 16.6 ± 2.2 | 22.2 ± 3.4 | N.S. |

| Total soil organic nitrogen (%) | 0.298 ± 0.071 | 0.282 ± 0.034 | 0.313 ± 0.033 | 0.381 ± 0.047 | N.S. |

| Plant-available phosphorus3 | 26.9 ± 5.0a | 19.4 ± 3.9a | 35.8 ± 8.5b | 46.4 ± 5.3b | 0.07 |

| OTU richness | Shannon diversity | Pielou’s evenness | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degree of urbanization | Chi23,16 = 16.79,p < 0.001 | F3,14 = 4.22, p = 0.026 | F3,11 = 5.14, p = 0.018 |

| Forest area (ha)1 | Chi21,15 = 1.47, p = 0.226 | – | F1,11 = 3.51, p = 0.088 |

| % forest within 500 m1 | Chi21,14 = 5.90, p = 0.015 | F1,14 = 1.82, p = 0.197 | F1,11 = 1.08, p = 0.322 |

| Plant species richness1 | – | – | F1,11 = 2.82 p = 0.123 |

| Tree species richness1 | Chi21,13 = 1.82, p = 0.177 | – | – |

| Soil moisture | Chi21,12 = 8.20, p = 0.004 | F1,14 = 1.68, p = 0.216 | F1,11 = 5.05, p = 0.046 |

| Soil pH | – | – | F1,11 = 1.23, p = 0.290 |

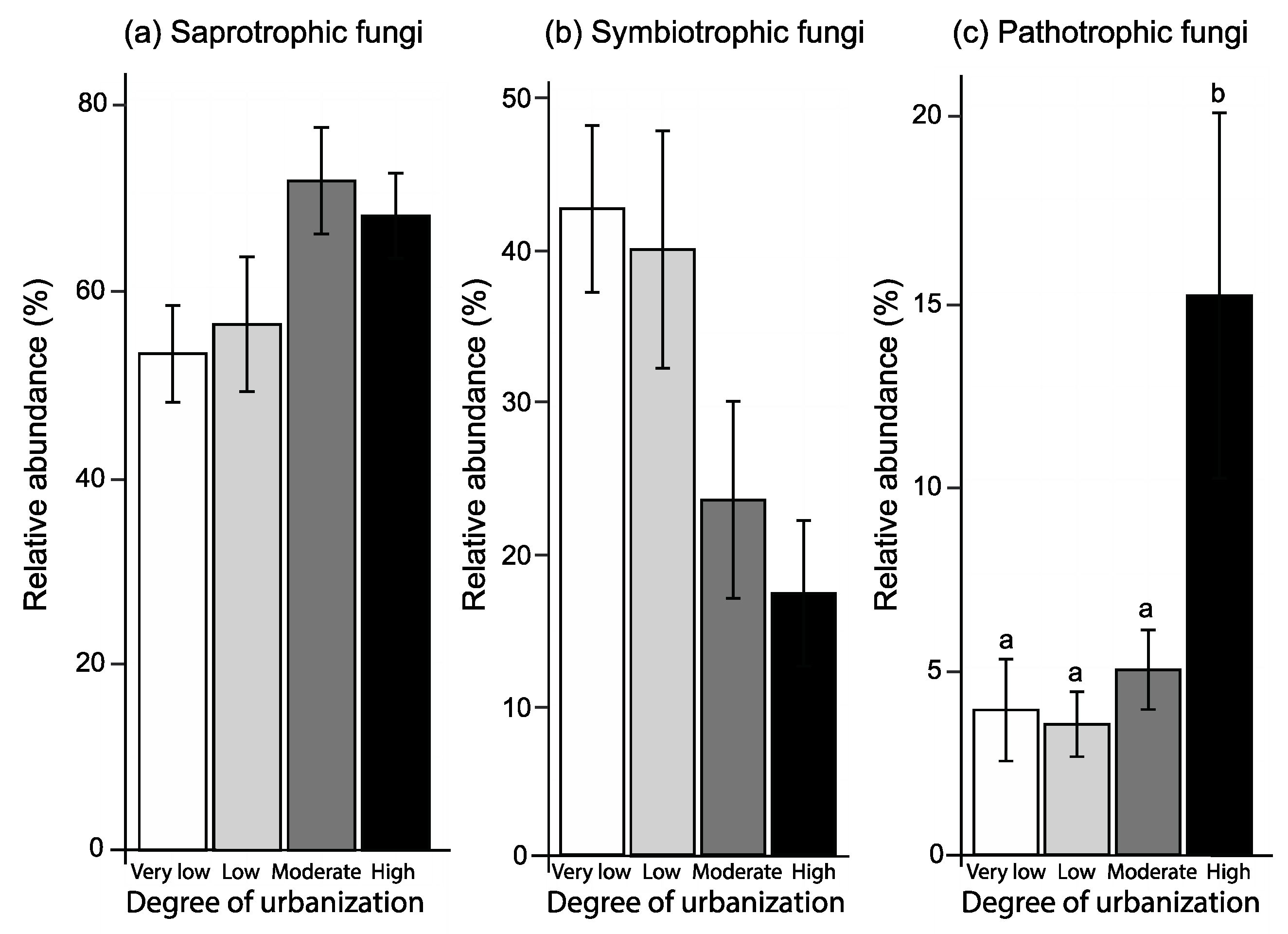

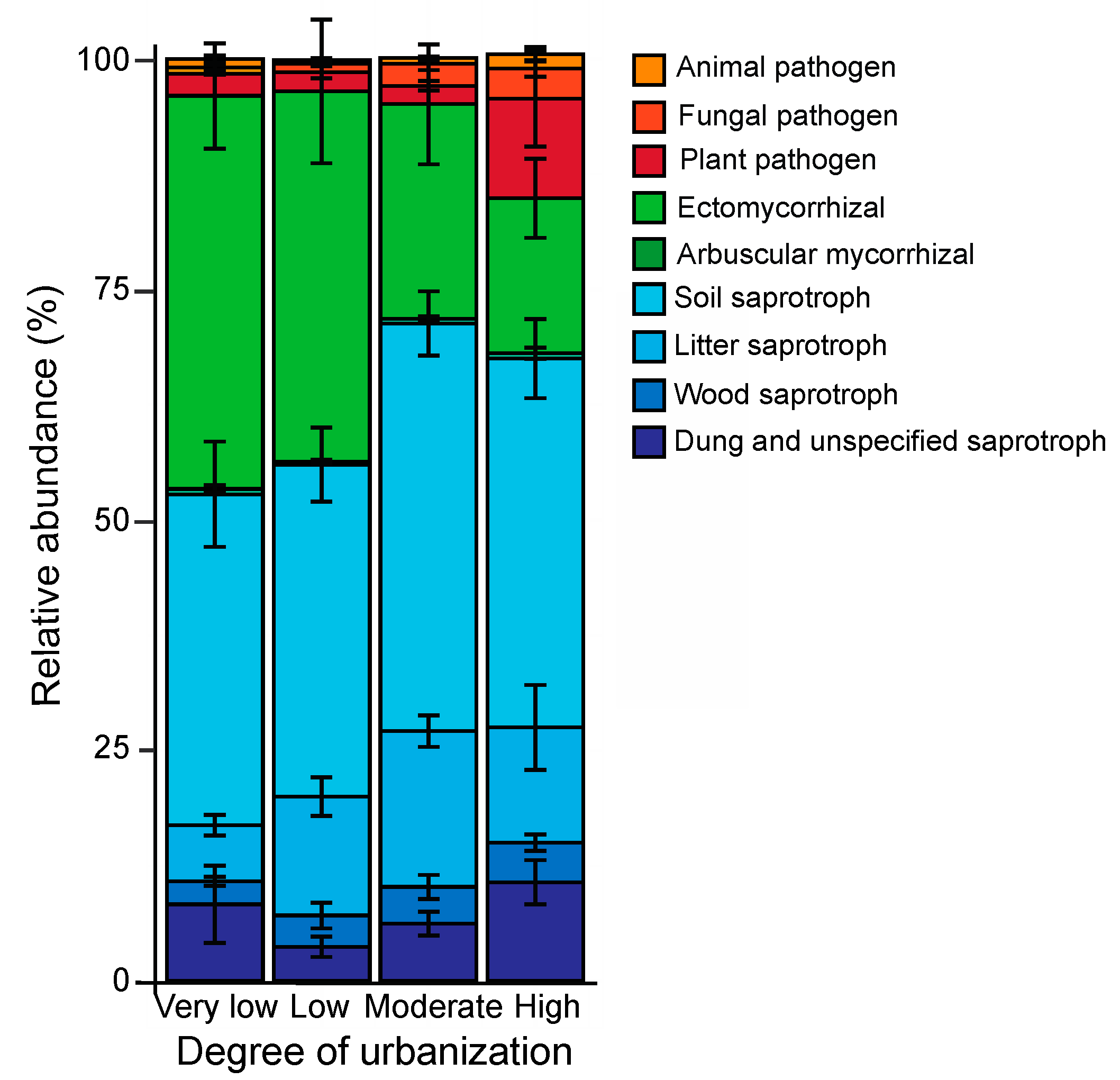

| Relative abundance of | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Saprotrophic fungi | Symbiotrophic fungi | Pathotrophic fungi | |

| Degree of urbanization | F3,13 = 3.16, p = 0.061 | F3,12 = 4.37, p = 0.026 | F3,13 = 5.24, p = 0.014 |

| Ground vegetation cover (%) | F1,13 = 1.47, p = 0.247 | F1,12 = 2.08, p = 0.175 | F1,13 = 1.25, p = 0.284 |

| Plant species richness1 | F1,13 = 2.55, p = 0.141 | F1,12 = 1.22, p = 0.290 | – |

| Tree species richness1 | – | F1,12 = 1.85, p = 0.198 | – |

| Soil moisture (%) | F1,13 = 4.10, p = 0.046 | – | F1,13 = 3.46, p = 0.084 |

| Soil pH | – | F1,12 = 3.17, p = 0.100 | F1,13 = 2.20, p = 0.162 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).