Submitted:

15 September 2023

Posted:

19 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| S.No. | Author | Year | Research Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ulrich | 1979 | Observed that patients having a view of nature from their window, recovered early and required fewer pain relievers compared to the ones faced walls. |

| 2 | Moore | 1981 | Found that prison residents looking at nature had 24% less frequent health care visits |

| 3 | Ulrich et al. | 1991 | Used electrocardiograms (ECGs) and measured pulse rate, frontal muscle tension and skin conductance as well as self-assessment of emotional states to further investigate the physiological relationship to nature. Both physiological and verbal findings indicated that recovery from stress was faster in a natural setting than in an urban one. |

| 4 | Berto | 2005 | Conducted three experiments involving 32 participants and concluded that the recovery environment and experience, including nature, greatly assisted in the recovery of mental fatigue. |

| 5 | Biederman and Vessel | 2006 | Suggested that seeing nature stimulates mu-opioid receptors in the human brain and the releases more endomorphin. |

| 6 | Taylor | 2006 | Found that fractal dimensions provoke stronger physiological responses, many of which indicate stress relief. |

| 7 | Hägerhäll et al. | 2008 -12 | Suggested that human responsiveness is not limited to direct exposure to green and there may be different human reactions to different forms of nature. |

| 8 | Ivarsson and Hagerhall | 2008 | Suggested the need for a better understanding of the morphology of the natural environment and its potential for recovery after the different results between gardens were observed. |

| 9 | Berman et al. | 2008 | Studied the interaction with nature in the restoration of direct attention and the improvement of cognitive function by comparing the urban and natural environments. They have also added that Environments that are devoid of any representation of nature can not only make people psychologically unwell and regressive in their behavior, but people can also display physical symptoms and responses. |

| 10 | Park and Mattson | 2008 | Suggested that plants should be used in hospitals as auxiliary healing mode. |

| 11 | Li et al. | 2011 | shown that exposure to nature reduces heart rate variability and pulse rate, lowers blood pressure, lowers cortisol, and increases parasympathetic nervous system activity, while sympathetic nervous system activity has been shown to decrease. These reactions contribute to improved cognitive function, working memory, and learning rates. Walking in the forest also revealed that levels of the hormone DHEA tended to increase. |

| 12 | Matsunaga et al. | 2011 | Showed that when older women were exposed to the hospital’s green rooftop forest, they were more physiologically relaxed and recovered. |

| 13 | Berman MG et al. | 2012 | Suggested that exposure to nature could be a valid supplement to treating depression and other disorders, with improvements to mood and memory span. |

| 14 | Tyrväinen et al. | 2014 | Investigated the psychological effects (resilience, vitality, mood, creativity) and the physiological effects of short-term immersion in nature. The results suggested that even short-term exposure to nature had a positive effect on stress compared to the urban built environment. |

| 15 | Guéguen and Stefan | 2016 | Observed that a short immersion in nature evoked a more positive mood and a greater desire to help others. |

2. Research Methodology

2.1. Location

2.2. Procedure

| 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design | Abbreviation | Atrium-I | Atrium-II | Atrium-III | Atrium-IV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nature in the space | Visual connection with nature | VC | ||||

| Connection with natural systems | CW | |||||

| Dynamic & diffuse Light | DD | |||||

| Non-Visual Connection with nature | NV | |||||

| Non-Rhythmic Sensory stimuli | NR | |||||

| Thermal & Airflow Variability | TA | |||||

| Presence of water | PW | |||||

| Natural Analogues | Biomorphic Forms & Patterns | BF | ||||

| Material Connection with Nature | MC | |||||

| Complexity & Order | CO | |||||

| Nature of the space | Prospect | PR | ||||

| Mystery | MY | |||||

| Refuge | RE | |||||

| Risk/Peril | RI | |||||

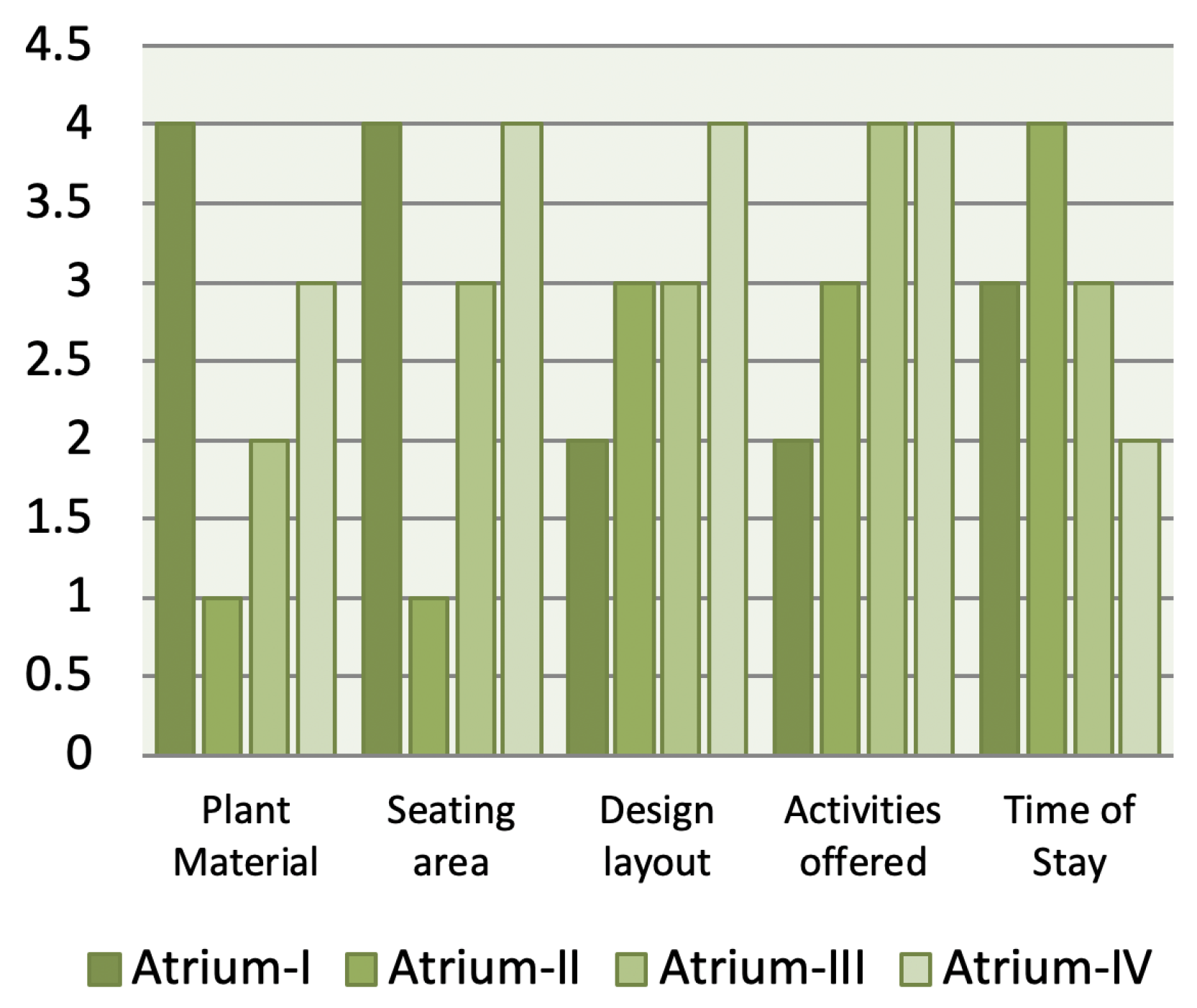

2.3. Results and Recommendation

| Design Elements | 5 Star (%) | 4 Star (%) | 3 Star (%) | 2 Star (%) | 1 Star (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atrium I | Aromatic Flowers (Murraya, Lavandula, Gardenia) | 67 | 28 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| Fixed & movable seating | 75 | 23 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Semi Covered Rest Area | 85 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 5 | |

| Atrium II | Water fountain | 72 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Water curtain | 58 | 12 | 3 | 28 | 2 | |

| Water Dip Therapy | 89 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Wall mounted waterfall | 69 | 31 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Meandering pathway | 48 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 39 | |

| Atrium III | Semi Covered Rest Area | 95 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Green pathway | 98 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Raised Flower Bed | 59 | 38 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Seating around pond | 73 | 12 | 11 | 2 | 2 | |

| Steps for exercise | 68 | 27 | 5 | 0 | 0 | |

| Atrium IV | Rest area with green bed | 97 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Small meeting area | 94 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Movable Furniture | 87 | 9 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| Organic shaped pond | 52 | 38 | 6 | 2 | 2 | |

| Sand track | 79 | 13 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

- Provision of more seating area or recliners to have a small nap in the A-II.

- More covered seating area in A-II

- A worship place or chanting of mantras.

- Pets or birds.

- Horticultural Therapy.

- A mini amphitheater for performing arts or to watch on occasion.

- Provision of Physiotherapy.

- More medicinal plants and label their names and benefits.

- Food cart or drinking fountain.

3. Discussion

- Bright colours.

- Aromatic Flowers.

- Use of water in different ways.

- Semi-covered rest area.

- Movable and comfortable furniture.

- Freedom of movement.

- Variety of spaces, like private, semi-private and public.

- Incorporating the principles of universal architecture to provide equal benefits to all.

- Materials chosen should not hinder the movement.

- 14 Patterns of Biophilic design, except- Risk, which comes under the `nature of the space’ as patients get scared and are reluctant to such kind of adventure. (Table 4)

- A worship place, meditation place or a space dedicated for group therapies.

- Plant materials should be non-allergic.

- Understanding Physiological, psychological and psychosocial needs of different users.

- Biomorphic forms and patterns.

- Create opportunities to socialize with others.

- Safety and security measures must be taken.

- The garden should be accessible at any time.

- Sufficient light and ventilation in an indoor setting.

- Familiar sculptures or design elements to make them comfortable in a new setting.

- Different rooms fulfilling various user requirements.

- Specifying elements that stimulate five senses.

- Hygiene and quality maintenance is required to contribute good health for patients as well as plants.

4. Conclusion and Future Work

References

- Ulrich, R.S. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 1984, 224, 420–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, E.O. A prison environment’s effect on health care service demands. Journal of environmental systems 1981, 11, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. Journal of environmental psychology 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berto, R. Exposure to restorative environments helps restore attentional capacity. Journal of environmental psychology 2005, 25, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biederman, I.; Vessel, E.A. Perceptual pleasure and the brain: A novel theory explains why the brain craves information and seeks it through the senses. American scientist 2006, 94, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.P. Reduction of physiological stress using fractal art and architecture. leonardo 2006, 39, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hägerhäll, C.M.; Laike, T.; Küller, M.; Marcheschi, E.; Boydston, C.; Taylor, R. Human physiological benefits of viewing nature: EEG responses to exact and statistical fractal patterns. Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology & Life Sciences 2015, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Ivarsson, C.T.; Hagerhall, C.M. The perceived restorativeness of gardens–Assessing the restorativeness of a mixed built and natural scene type. Urban forestry & urban greening 2008, 7, 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Berman, M.G.; Jonides, J.; Kaplan, S. The cognitive benefits of interacting with nature. Psychological science 2008, 19, 1207–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Mattson, R.H. Effects of flowering and foliage plants in hospital rooms on patients recovering from abdominal surgery. HortTechnology 2008, 18, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Otsuka, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Wakayama, Y.; Inagaki, H.; Katsumata, M.; Hirata, Y.; Li, Y.; Hirata, K.; Shimizu, T.; others. Acute effects of walking in forest environments on cardiovascular and metabolic parameters. European journal of applied physiology 2011, 111, 2845–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsunaga, K.; Park, B.J.; Kobayashi, H.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiologically relaxing effect of a hospital rooftop forest on older women requiring care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2011, 59, 2162–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyrväinen, L.; Ojala, A.; Korpela, K.; Lanki, T.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Kagawa, T. The influence of urban green environments on stress relief measures: A field experiment. Journal of environmental psychology 2014, 38, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guéguen, N.; Stefan, J. “Green altruism” short immersion in natural green environments and helping behavior. Environment and behavior 2016, 48, 324–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilani, A. Design & health: The therapeutic benefits of design; Svensk byggtjänst, 2001.

- Diette, G.B.; Lechtzin, N.; Haponik, E.; Devrotes, A.; Rubin, H.R. Distraction therapy with nature sights and sounds reduces pain during flexible bronchoscopy: A complementary approach to routine analgesia. Chest 2003, 123, 941–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, U.; Weisman, G.D. Holding on to home: Designing environments for people with dementia. (No Title) 1991.

- Kellert, S.R. Building for life: Designing and understanding the human-nature connection. Renewable Resources Journal 2006, 24, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The experience of nature: A psychological perspective; Cambridge university press, 1989.

- Ulrich, R.; Gilpin, L. Healing arts. Nursing 1999, 4, 128–133. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, A. Innovation in the Design of the ICU. Minnesota Physician 2004, pp. 32–36.

- Hastuti, A.S.O.; Lorica, J. The Effect of Healing Garden to Improve the Patients Healing: An Integrative Literature Review. Journal of Health and Caring Sciences 2020, 2, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, C.C.; Barnes, M. Gardens in healthcare facilities: Uses, therapeutic benefits, and design recommendations; Center for Health Design Martinez, CA, 1995.

- Miller, W.L.; Crabtree, B.F. Healing landscapes: patients, relationships, and creating optimal healing places. Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine 2005, 11, s–41. [Google Scholar]

- Pouya, S.; Demirel, Ö. What is a healing garden? Akdeniz University Journal of the Faculty of Agriculture 2015, 28, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Simson, S.; Straus, M. Horticulture as therapy: Principles and practice; CRC Press, 1997.

- Stigsdotter, U.; Grahn, P. What makes a garden a healing garden. Journal of therapeutic Horticulture 2002, 13, 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S. Health benefits of gardens in hospitals. Paper for conference, Plants for People International Exhibition Floriade, 2002, Vol. 17, p. 2010.

- Brown, T.; McLafferty, S.; Moon, G.; others. A companion to health and medical geography; Wiley Online Library, 2010.

- Marcus, C.C.; Barnes, M. Healing gardens: Therapeutic benefits and design recommendations; Vol. 4, John Wiley & Sons, 1999.

- Hashemin, S.A.; Kazemi, A.; Bemanian, M. Examining the Influence of Healing Garden on Mental Health of the Patients by Emphasizing Stress Reduction. Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2020, 21, 263–276. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, C.O.; Browning, W.D.; Clancy, J.O.; Andrews, S.L.; Kallianpurkar, N.B. Biophilic design patterns: emerging nature-based parameters for health and well-being in the built environment. ArchNet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research 2014, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraskevopoulou, A.T.; Kamperi, E. Design of hospital healing gardens linked to pre-or post-occupancy research findings. Frontiers of Architectural Research 2018, 7, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Questions | Preference- A | Preference- B | Preference- C | Preference- D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How do you feel when you spend time I a garden? |

Calmer,more relaxed, less stressed | Better, more positive | Refreshed,Stronger | No change |

| 47% | 78% | 22% | 3% | |

| What activity do you prefer in a garden? |

To walk or exercise | To meditate | To sleep | To eat |

| 50% | 32% | 12% | 6% | |

| What element do you like the most in a garden? |

Flowers, Plants | Water Fountain | Comfortable seating | Birds and animals |

| 49% | 23% | 15% | 13% | |

| What’s the thing that bother you most here? |

No movement, need to be on bed | Can’t Socialize | Smell | Nothing |

| 60% | 25% | 12% | 6% | |

| If asked to spend some time in garden would you like to come out? |

Yes | Doesn’t Matter | No | |

| 82% | 13% | 5% | 13% | |

| What time should the garden be accessible? | Every time | Morning | Evening | Night |

| 75% | 14% | 8% | 3% | |

| Do you feel stressed out when you need to visit again for check ups? |

Yes | Sometimes | No | |

| 56% | 35% | 9% | ||

| What kind of furniture would you prefer? | Movable | Fixed | Doesn’t matter | |

| 60% | 36% | 3% | ||

| What kind of colors would you prefer? | Bright | Light | Doesn’t matter | |

| 73% | 23% | 3% | ||

| Would you prefer a Garden view from your window? |

Yes | Doesn’t Matter | No | |

| 92% | 8% |

| Type of sound | Effect on human mood |

|---|---|

| Ocean Waves | Positive, Restorative |

| Waterfall | Calming, Relaxing, Helps In Sleep |

| Rainfall | Exciting, Generation Of Thoughts |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).