Submitted:

18 September 2023

Posted:

20 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

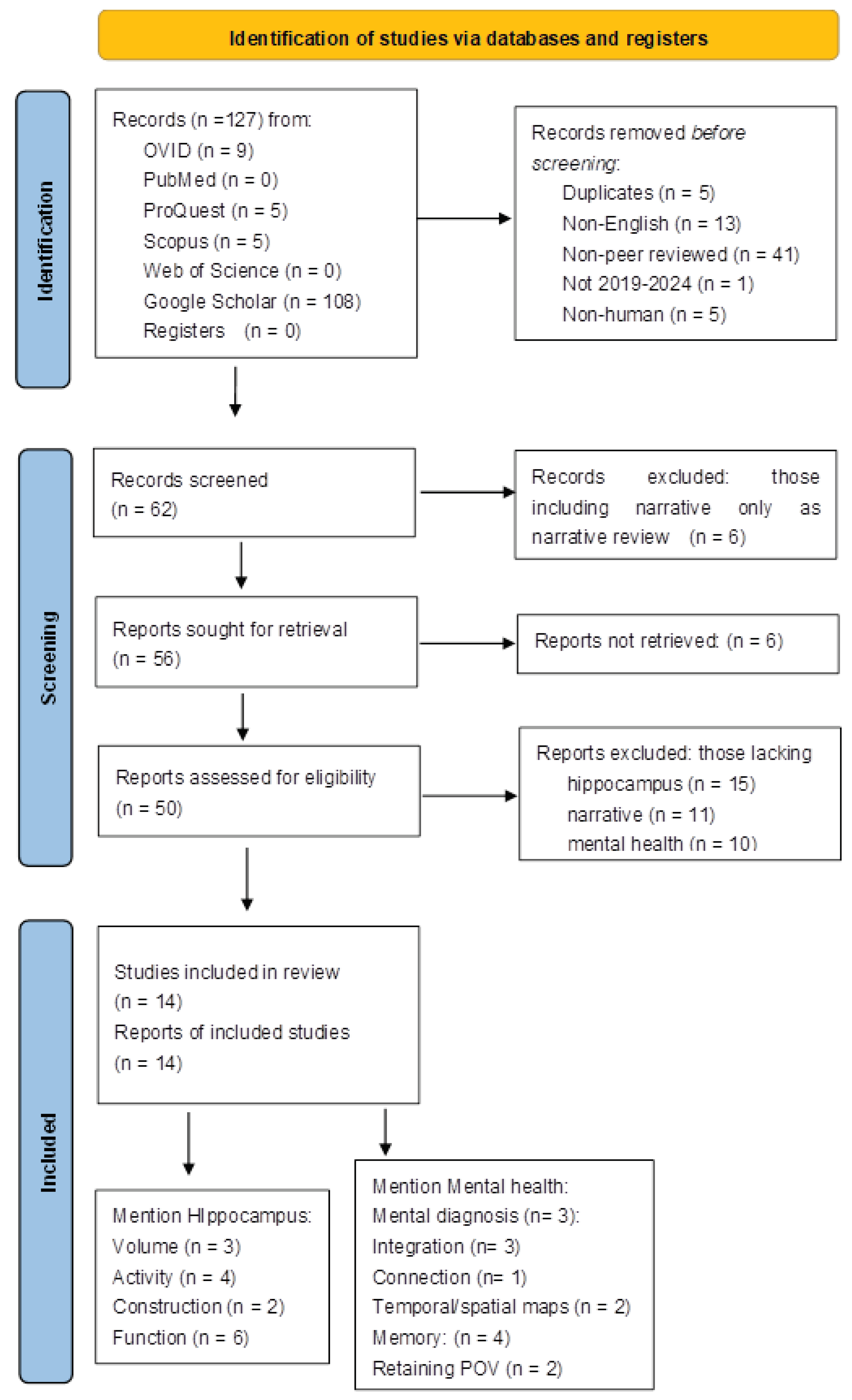

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Searched Records Returned

2.3. Searched Reports Included

3. Results

| # | Author, Publication Date | Hippocampal Function—Mental Health |

|---|---|---|

| 24 | Dee., et al., 2023 | With volume ↓—DNA altered from early childhood trauma |

| 25 | Siegel & Drulis, 2023 | With ↓ activity—impaired functional & structural integration |

| 26 | Traynor, et at., 2023 | ↓ rs-fMRI activity—connectivity, self-interpersonal impairment |

| 27 | Raver & McElheran, 2022 | ↓ volume & activity—limited processing of mental events |

| 28 | Magni et al., 2019 | ↓ volume— clinical priority regarding BPD |

| 29 | Kelly & O’Connell, 2020 | Storied visualization— connectivity: pivotal role in morality |

| 30 | Larner, 2022 | Semantic retrieval— time/space confusion separate |

| 31 | Stoyanov, et. al., 2019 | Highest peaks fMRI— cross-validation: depression, paranoia |

| 32 | Thorpe, 2022 | “Concept cells”—cognitive spatial & temporal maps |

| 33 | Pine, 2022 | Leptin signaling— health related to memory of food |

| 34 | Michelmann, et al., 2022 | Memory replay—contracted temporal order of things |

| 35 | Sriyanah, et. al., 2022 | High cortisol—memory consolidation chaotic, longer REM |

| 36 | Yazin, et al., 2021 | Contextual binding— dual nature to episodic memory recall |

| 37 | Kirsch, et al., 2021 | Lesions—associated with learned counterfactual beliefs |

3.1. Types of Mention of the Hippocampus

3.1.1. Volume

3.1.2. Activity

3.1.3. Construction

3.1.4. Function

3.2. Types of Mention of Mental Health

3.2.1. Mental Diagnosis

3.2.2. Integration

3.2.3. Connection

3.2.4. Temporal/Spatial Maps

3.2.5. Memory

3.2.6. Point of View

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications of the Articles Reviewed

4.2. Health Narratives Research Process

4.2.1. Role of the Facilitator

4.2.2. The Prompts

4.2.3. Research Program

4.2.4. Participation

4.2.5. Feedback

- -

- Self-awareness and assessing my goals when I join a new research project in the future.

- -

- It helped me remind myself that I am much more capable than I think, and know that I have written down what I am interested in health research, it will be nice to be able to go back to that response when I am doubting myself.

- -

- This process helped me clarify my ideas and articulate what about the research process is helpful or unhelpful to me as a researcher. I think that teaching others and presenting new knowledge/insights is the best way to crystalize concepts learned, explore working hypotheses, or develop questions for future inquiry.

- -

- Reflective writing project has taught me self-awareness and the improvement I made in research over the years.

- -

- It was helpful to have to set time aside and really reflect on why I was interested in health research. As someone who is only beginning to enter into the job market, it’s nice to have a better sense of myself and the type of work I like to do.

- -

- I appreciated the opportunity for self-reflection based on the nuances of the prompt. I felt that there was a real dialogue and that I learned something from the exchange of ideas and personal research practices shared and explained.

- -

- I would recommend the health narrative process to other people because it would help to explore one's research in a more wholistic manner, not only in terms of the research process but also in terms of what the research would mean to you and your life personally. I think it's important for a researcher to explore what health research means to them and their life personally because I think that's one thing that keeps people motivated to do what they do. If you don't make the research a part of what you do it will more difficult to pursue it long term.

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nitz, D. Neuroscience The inside story on place cells. Nature 2009, 461, 889–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, C.D.; Collman, F.; Dombeck, D.A.; Tank, D.W. ntracellular dynamics of hippocampal place cells during virtual navigation. Nature, 2009, 461, 941–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iglói, K.; Zaoui, M.; Berthoz, A.; Rondi-Reig, L. Sequential egocentric strategy is acquired as early as allocentric strategy: Parallel acquisition of these two navigation strategies. Hippocampus 2009, 19, 1199–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doron, A.; Rubin, A.; Benmelech-Chovav, A.; Benaim, N.; Carmi, T.; Refaeli, R.; Novick, N.; Kreisel, T.; Ziv, Y.; Goshen, I. Hippocampal astrocytes encode reward location. Nature 2022, 609, 772–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Hu, G.; Meng, X.; Guo, J.; Fang, H.; Jiang, H.; Weng, D. Altered functional connectivity of the hippocampus with the sensorimotor cortex induced by long-term experience of virtual hand illusion. Virtual Reality 2023, 27, 2703–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugar, J.; Moser, M.B. Episodic memory: Neuronal codes for what, where, and when. Hippocampus 2019, 29, 1190–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, K.A. Episodic memories: how do the hippocampus and the entorhinal ring attractors cooperate to create them? Front. Systems Neurosci. 2020, 14, 559168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mace, J.H.; Clevinger, A.M. The associative nature of episodic memories. In The organization and structure of autobiographical memory; Mace, J., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, U.K, 2019; pp. 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koban, L.; Gianaros, P.J.; Kober, H.; Wager, T.D. The self in context: brain systems linking mental and physical health. Nature Rev. Neurosci. 2021, 22, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, J.; Simms, L.J. Construct validation of narrative coherence: Exploring links with personality functioning and psychopathology. Personality Disorders: Theory, Res. Treatment 2022, 13, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, D.S.; Wise, S.P.; Murray, E.A. Evolution, emotion, and episodic engagement. Amer. J. Psychia. 2021, 178, 701–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Khalil, H.; Larsen, P.; Marnie, C.; Pollock, D.; Tricco, A.C.; Munn, Z. Best practice guidance and reporting items for the development of scoping review protocols. JBI evidence synth. 2022, 20, 953–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danieli, K.; Guyon, A.; Bethus, I. Episodic Memory formation: A review of complex Hippocampus input pathways. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharm. Bio. Psychia. 2023, 126, 110757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonagy, P.; Luyten, P.; Allison, E.; Campbell, C. Mentalizing, epistemic trust and the phenomenology of psychotherapy. Psychopathol. 2019, 52, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maroney, D.I. The Imagine Project[TM]: Using Expressive Writing to Help Children Overcome Stress and Trauma. Pediatric Nursing 2020, 46, 300–311. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, C. Enhancing Hopeful Resilience Regarding Depression and Anxiety with a Narrative Method of Ordering Memory Effective in Researchers Experiencing Burnout. Challenges 2022, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, L.; Oexle, N.; Bushman, M.; Glover, L.; Lewy, S.; Armas, S.A.; Qin, S. To share or not to share? Evaluation of a strategic disclosure program for suicide attempt survivors. Death Studies 2023, 4, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; Chou, R.; Glanville, J.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Lalu, M.M.; Li, T.; Loder, E.W.; Mayo-Wilson, E.; McDonald, S.; McGuinness, L.A.; Stewart, L.A.; Thomas, J.; Tricco, A.C.; Welch, V.A.; Whiting, P.; McKenzie, J.E. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, C.; Dos Santos, K.B.; Pap, R. Practical guidance for knowledge synthesis: Scoping review methods. Asian Nursing Res. 2019, 13, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salameh, J.-P.; Bossuyt, P.M.; McGrath, T.A.; Thombs, B.D.; Hyde, C.J.; Macaskill, P.; Deeks, J.J.; Leeflang, M.; Korevaar, D.A.; Whiting, P.; Takwoingi, Y.; Reitsma, J.B.; Cohen, J.F.; Frank, R.A.; Hunt, H.A.; Hooft, L.; Rutjes, A.W.S.; Willis, B.H.; Gatsonis, C.; Levis, B.; Moher, D.; McInnes, M.D.F. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies (PRISMA-DTA): explanation, elaboration, and checklist. BMJ 2020, 370, m2632–m2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- . Fins, J.J. Resuscitating patient rights during the pandemic: COVID-19 and the risk of resurgent paternalism: CQ. Cambridge Quart. Healthcare Ethics 2021, 30, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fins, J.J. Two patients: Professional formation before “Narrative medicine”: CQ. Cambridge Quart. Healthcare Ethics 2020, 29, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, H.P. The Cambridge Introduction to Narrative; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, U.K., 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dee, G; Ryznar, R. ; Dee, C. Epigenetic Changes Associated with Different Types of Stressors and Suicide. Cells 2023, 12, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, D.J.; Drulis, C. An interpersonal neurobiology perspective on the mind and mental health: personal, public, and planetary well-being. Ann. Gen. Psychia. 2023, 22, 5–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traynor, J.M.; Wrege, J.S.; Walter, M.; Ruocco, A. C. Dimensional personality impairment is associated with disruptions in intrinsic intralimbic functional connectivity. Psychol..Med. 2023, 53, 1323–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raver, J.L.; McElheran, M. A trauma-informed approach is needed to reduce police misconduct. Indust. Organiz. Psychol. 2022, 15, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magni, L.R.; Carcione, A.; Ferrari, C.; Semerari, A.; Riccardi, I.; Nicolo’, G.; Lanfredi, M.; Pedrini, L.; Cotelli, M.; Bocchio, L.; Pievani, M.; Gasparotti, R.; Rossi, R. Neurobiological and clinical effect of metacognitive interpersonal therapy vs structured clinical model: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychia. 2019, 19, 195–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.; O’Connell, R. Can Neuroscience Change the Way We View Morality? Neuron 2020, 108, 604–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larner, A.J. Investigation of TGA (1): Neuropsychology, Neurophysiology and Other Investigations. In Transient Global Amnesia: From Patient Encounter to Clinical Neuroscience; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyanov, D.; Kandilarova, S.; Paunova, R.; Barranco Garcia, J.; Latypova, A.; Kherif, F. Cross-validation of functional MRI and paranoid-depressive scale: Results from multivariate analysis. Front. Psychia. 2019, 10, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, L. Atomic Event Concepts in Perception, Action, and Belief. J. Amer. Philoso. Assoc. 2022, 8, 110–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, L. Food Memory and Food Imagination at Auschwitz. In Food in Memory and Imagination: Space, Place And, Taste; Forrest, B., de St. Maurice, G., Eds.; Bloomsbury Academic: London, U.K, 2022; pp. 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelmann, S.; Staresina, B.P.; Bowman, H.; Hanslmayr, S. Speed of time-compressed forward replay flexibly changes in human episodic memory. Nature Human Behav. 2019, 3, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriyanah, N.; Efendi, S.; Syatiani, S.; Nurleli, N.; Nurdin, S. Relationship between hospitalization stress and changes in sleep patterns in children aged 3-6 years in the Al-Fajar Room of Haji Hospital, Makassar. Int. J. Health Sci. 2022, 6, 608–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazin, F.; Das, M.; Banerjee, A.; Roy, D. Contextual prediction errors reorganize naturalistic episodic memories in time. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirsch, L.P.; Mathys, C.; Papadaki, C.; Talelli, P.; Friston, K.; Moro, V.; Fotopoulou, A. Updating beliefs beyond the here-and-now: the counter-factual self in anosognosia for hemiplegia. Brain Commun. 2021, 3, fcab098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherin, J.E.; Nemeroff, C.B. Post-traumatic stress disorder: The neurobiological impact of psychological trauma. Dialogues Clin, Neurosci. 2011, 13, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leichsenring, F.; Leibing, E.;Kruse, J.; New, A.S.; Leweke, F. Borderline personality disorder. Lancet 2011, 377, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, P.M.; Wenzel, A.; Borges, K.T.; Porto, C.R.; Caminha, R.M.; de Oliveira, I.R. Volumes of the hippocampus and amygdala in patients with borderline personality disorder: a meta-analysis. J Personal Disord. 2009, 23, 333–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, M.; Hazlett, E.A.; Avedon, J.B.; Siever, D.R.; Chu, K.W.; New, A.S. Anterior cingulate volume reduction in adolescents with borderline personality disorder and co-morbid major depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2011, 45, 803–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, R.; Lanfredi, M.; Pievani, M.; Boccardi, M.; Beneduce, R.; Rillosi, L; Giannakopoulos, P. ; Thompson, P.M.; Ross,i G.; Frisoni, G.B. Volumetric and topographic differences in hippocampal subdivisions in borderline personality and bipolar disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2012, 20, 132–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korgaonkar, M.S.; Fornito, A.; Williams, L.M.; Grieve, S.M. Abnormal structural networks characterize major depressive disorder: a connectome analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2014, 76, 567–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, P.B.; Telzer, E.H. Structural connectomics of anxious arousal in early adolescence: translating clinical and ethological findings. NeuroImage Clin. 2017, 16, 604–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tymofiyeva, O.; Ziv, E.; Barkovich, A.J.; Hess, C.P.; Xu, D. Brain without anatomy: construction and comparison of fully network-driven structural MRI connectomes. PLoS ONE. 2014, 9, e96196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ban, S.; Normand, E. Spatial Cognitive Abilities in Foraging Chimpanzees. In The Chimpanzees of the Taï Forest: 40 Years of Research; Boesch, C., Wittig, R.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, U.S.A, 2019; pp. 440–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janmaat, K.R.L. Temporal Cognition in Taï Chimpanzees. In The Chimpanzees of the Taï Forest: 40 Years of Research; Boesch, C., Wittig, R.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, U.S.A, 2019; pp. 451–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ropper, A.H. Transient global amnesia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandikci, V.; Ebert, A.; Hoyer, C.; Platten, M.; Szabo, K. Impaired semantic memory during acute transient global amnesia. J. Neuropsychol. 2022, 16, 149–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schöberl, F.; Irving, S.; Pradhan, C.; Bardins, S.; Trapp, C.; Schneider, E.; Kugler, G.; Bartenstein, P.; Dieterich, M.; Brandt, T.; Zwergal, A. Prolonged allocentric navigation deficits indicate hippocampal damage in TGA. Neurology 2019, 92, e234–e243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanoski, S.E.; Hayes, M.R.; Greenwald, H.S.; Fortin, S.M.; Gianessi, C.A.; Gilbert, J.R.; Grill, H.J. Hippocampal leptin signaling reduces food intake and modulates food-related memory processing. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011, 36, 1859–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Ré, C.; Souza, J.M.; Fróes, F.; Taday, J.; Dos Santos, J.P.; Rodrigues, L.; Sesterheim, P.; Gonçalves, C.A.; Leite, M.C. Neuroinflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide leads to memory impairment and alterations in hippocampal leptin signaling. Behav. Brain Res. 2020, 379, 112360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonelinas, A.P.; Ranganath, C.; Ekstrom, A.D.; Wiltgen, B.J. A contextual binding theory of episodic memory: systems consolidation reconsidered. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2019, 20, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bein, O.; Duncan, K.; Davachi, L. Mnemonic prediction errors bias hippocampal states. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestler, E.J. Transgenerational Epigenetic Contributions to Stress Responses: Fact or Fiction? PLoS Biol. 2016, 14, e1002426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, M.K. Environmental stress and epigenetic transgenerational inheritance. BMCMed. 2014, 12, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Švorcová, J. Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance of Traumatic Experience in Mammals. Genes 2023, 14, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bikos, L.J. “It’s all window dressing:” Canadian police officers’ perceptions of mental health stigma in their workplace. Policing: Int. J. Police Strat. Manage. 2020, 44, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, R.N.; Afifi, T.O.; Taillieu, T.; Turner, S.; Mason, J.E.; Ricciardelli, R.; McCreary, D.R.; Vaughan, A.D.; Anderson, G.S.; Krakauer, R.L.; Donnelly, E.A.; 2nd, Camp, R.; Groll, D.; Cramm, H.A.; MacPhee, R.S.; Griffiths, C.T. Assessing the relative impact of diverse stressors among public safety personnel. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health 2020, 17, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardelli, R.; Czarnuch, S.; Carleton, R.N.; Gacek, J.; Shewmake, J. Canadian public safety personnel and occupational stressors: How PSP interpret stressors on duty. . Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health 2020, 17, 4736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- . Bonasia, K.; Blommesteyn, J.; Moscovitch, M. Memory and navigation: compression of space varies with route length and turns. Hippocampus 2016, 26, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larner, A.J. (Ed.) Cognitive screening instruments. A practical approach, 2nd ed.; Springer: London, U.K., 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wible, C.G. Hippocampal temporal-parietal junction interaction in the production of psychotic symptoms: a framework for understanding the schizophrenic syndrome. Front. Human Neurosci. 2012, 6, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besharati, S.; Forkel, S.J.; Kopelman, M.; Solms, M.; Jenkinson, P.M.; Fotopoulou, A. Mentalizing the body: Spatial and social cognition in anosognosia for hemiplegia. Brain. 2016, 139, 971–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankland, R.; Tessier, D.; Strub, L.; Gauchet, A.; Baeyens, C. Improving mental health and well-being through informal mindfulness practices: an intervention study. Appl. Psychol.: Health Well-Being 2021, 13, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gál, É.; Ștefan, S.; Cristea, I.A. The efficacy of mindfulness meditation apps in enhancing users’ well-being and mental health related outcomes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 279, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.L.; Schülke, R.; Vatansever, D.; Xi, D.; Yan, J.; Zhao, H.; Xie, X.; Feng, J.; Chen, M.Y.; Sahakian, B.J.; Wang, S. Mindfulness practice for protecting mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuch, I.; Peters, N.; Lohner, M.S.; Muss, C.; Aprea, C.; Fürstenau, B. Resilience training programs in organizational contexts: A scoping review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieckert, A.; Schuit, E.; Bleijenberg, N.; Ten Cate, D.; de Lange, W.; de Man-van Ginkel, J.M.; Mathijssen, E.; Smit, L.C.; Stalpers, D.; Schoonhoven, L.; Veldhuizen, J.D. How can we build and maintain the resilience of our health care professionals during COVID-19? Recommendations based on a scoping review. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e043718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungar, M.; Theron, L. Resilience and mental health: How multisystemic processes contribute to positive outcomes. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christopher, M.; Bowen, S.; Witkiewitz, K. Mindfulness-based resilience training for aggression, stress and health in law enforcement officers: study protocol for a multisite, randomized, single-blind clinical feasibility trial. Trials 2020, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Burn-out an "occupational phenomenon": International Classification of Diseases. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases (accessed on 8 September 2023).

- Igneski, V. Individual Duties in Unstructured Collective Contexts. In Collectivity–Ontology, Ethics, and Social Justice; Hess, K.M., Igneski, V., Isaacs, T., Eds.; Rowman & Littlefield International Ltd.: London, U.K, 2018; pp. 133–152. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, C. Report on Digital Literacy in Academic Meetings during the 2020 COVID-19 Lockdown. Challenges 2020, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. Reconsidering Privilege: How to Structure Writing Prompts to Develop Narrative. Survive Thrive 2020, 5, 3. Available online: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/survive_thrive/vol5/iss2/3 (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- Nash, C. Online Meeting Challenges in a Research Group Resulting from COVID-19 Limitations. Challenges 2021, 12, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. Team Mindfulness in Online Academic Meetings to Reduce Burnout. Challenges 2023, 14, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntinda, K. 2018. Narrative research. In Handbook of research methods in health social sciences; Liamputtong, P, Ed.; Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.: Singapore, 2019; pp. 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renjith, V.; Yesodharan, R.; Noronha, J.A.; Ladd, E.; George, A. Qualitative methods in health care research. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 12, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biljecki, F.; Ito, K. Street view imagery in urban analytics and GIS: A review. Lands Urban Plan 2021, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, T.; Lienert, P.; Denne, E.; Singh, J.P. A general model of cognitive bias in human judgment and systematic review specific to forensic mental health. Law and human behavior 2022, 46(2), 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).