1. Introduction

The study of population growth got considerable interest in the eighteenth century, notably with the seminal work by Malthus [

1]. Malthus proposed an exponential growth model for human population and deduced that, ultimately, the population would surpass the capacity to sustain an adequate food supply.

However, the model’s assumptions overlooked crucial factors like the environment and interactions between populations of different species, elements pivotal to understanding population growth dynamics. Consequently, this model did not endure the test of time, particularly as it was proven to be inaccurate in technologically advanced nations.

Remarkably, the publication by Malthus [

1] served as a catalyst for heightened curiosity surrounding the ecological conundrum involving the interaction between predator and prey populations—an issue that has captivated the attention of scholars across various scientific domains. The initial endeavors to address this complex problem through mathematical formulations are commonly attributed to the pioneering and independent contributions of Lotka [

2] and Volterra [

3].

In the realm of fisheries management, a paramount challenge is to ensure sustainable practices that uphold the delicate ecological balance of marine ecosystems while meeting the needs of a growing human population (Pierotti [

4], Benz et al. [

5]). Achieving this delicate equilibrium requires a profound understanding of the intricate dynamics governing fish populations and their interdependence within the ecosystem. Mathematical models, particularly the Lotka-Volterra equations, stand as a pillar of scientific inquiry, providing a formal framework to comprehend the dynamics of predator-prey interactions (Amirian et al. [

6], Whipple et al. [

7], Manaf et al. [

8]).

At the core of the Lotka-Volterra equations lies the essence of dynamic interaction between species. These differential equations elucidate how changes in the population size of predators and prey influence each other over time. The Lotka-Volterra model encapsulates the fundamental principles of population growth, incorporating birth, death, predation, and competition into a system of equations. These equations form the cornerstone of mathematical ecology, enabling a quantitative understanding of the inherent complexities within ecological systems.

The Lotka-Volterra model assumes the following about the environment and evolution of the predator and prey population:

The prey population have an unlimited food supply at all times.

The prey population increases at a rate (proportional to the number of prey) but is simultaneously destroyed by predators at a rate (proportional to the product of the numbers of predator and prey).

The predator population decreases at a rate (proportional to the number of predators), but increases at a rate (again proportional to the product of the numbers of predator and prey).

The first and simplest predator-prey model (Lotka [

2], Volterra [

3], Pierotti [

4]) is given by the nonlinear system of first-order ordinary differential equations

The aim of this study is to explore the potential of the Lotka-Volterra equations in providing a mathematical approach to understanding the dynamics of sustainable fisheries. By adapting these equations to depict fish populations, we seek to unravel the intricate relationships that govern the sustainable coexistence of different fish species. This endeavor is vital in devising effective and sustainable fisheries management strategies, which are paramount to the preservation of marine biodiversity and the stability of ecosystems.

In this pursuit, we delve into the mathematical intricacies of the Lotka-Volterra equations, elucidating their applicability in modeling fish population dynamics. By unveiling the mathematical essence of these equations, we aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of their potential in guiding sustainable fishing practices. Through rigorous analysis and simulation, we showcase the ability of the Lotka-Volterra equations to predict population trends, thus paving the way for informed decision-making in the realm of fisheries management. The mathematical tone of this exploration shall underscore the precision and depth that mathematical modeling brings to the crucial domain of sustainable fisheries, emphasizing the need for analytical rigor in safeguarding our marine resources.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Identification of Problem

In Darwin [

9], the author astutely observed that, given the production of more individuals than can possibly survive, a perpetual struggle for existence ensues. This inescapable truth manifests as a competition among individuals, not only with their own species but also with other distinct species, as they contend for limited resources.

In the present study, we delve into the intricate dynamics governing predator-prey interactions. Predators, in their pursuit of sustenance, prey upon individuals from the prey population, which, in turn, sustains itself by feeding on the readily available natural resources within the environment. A delicate balance emerges: if the predators consume an excessive number of prey, depleting their abundance, the predators themselves face a severe reduction in their food supply, a scenario leading inexorably to starvation.

This interdependence sets the stage for a cyclical pattern. A decline in the predator population triggers a notable surge in the prey population as a result of reduced predation pressure. The burgeoning prey population, in turn, augments the food supply for the predators, leading to an upswing in their numbers. Consequently, more predators engage in intensified predation, initiating the cycle anew.

In the face of this perpetual ebb and flow, a fundamental question arises: does this cycle persist indefinitely, or does it culminate in the extinction of one of the species involved? The capacity to address this profound question holds profound implications in ecology.

The exploration of this predator-prey relationship not only sheds light on the intricate workings of ecological systems but also finds relevance in a multitude of scientific disciplines, illuminating the nuanced interplay between species and the broader implications for biodiversity, ecosystem stability, and conservation efforts.

2.2. Model Formulation and Assumptions

In this work, we modify the classical Lotka-Volterra equation by introducing the degree of internal competition of the predator and prey for their limited resources. We assume that the degree of internal competition of the predator and prey are proportional to the square of the predator and prey populations, i.e.

and

respectively. Hence, the our modified Lotka-Volterra predator-prey model is given as

where

are positive constants.

represents the rate of change in prey population over time.

represents the rate of change in predator population over time.

a is the intrinsic growth rate of the prey species.

b is the rate at which predators consume prey.

c is the death rate of predators.

d is the rate at which predators reproduce based on prey consumption.

e degree of internal competition in prey population

f degree of internal competition in predator population

2.3. Stability Property of Model Solution

In order to scrutinize the dynamics of the system under examination, it becomes necessary to explore certain attributes of the system across different parameter values within the model. In this context, we shall explore the critical points, eigenvalues, phase portrait, and the overall stability of the model in question.

2.3.1. Critical Points of Model

To identify the critical points of the model (

2), we set

and

and proceed to solve. In contrast to linear systems, a nonlinear system may possess zero, one, two, three, or multiple critical points. Given the potential presence of numerous critical points on the phase portrait, each trajectory can be influenced by more than one such point. Consequently, this leads to a notably chaotic appearance of the phase portrait. Thus, determining the type and stability of each critical point becomes a localized task, necessitating a case-by-case evaluation.

Given the non-trivial nature of obtaining solutions

and

through direct observation, we opt to utilize Mathematica

’s integrated equation-solving function. By employing this approach to solve the system for

and

, we identify four critical points within the system. Consequently, the critical points for the model (

2) are as follows:

Notably, the values of parameters a, b, c, d, e, and f exert a significant influence on three of the critical points within the system.

2.3.2. Eigenvalues of Model

The matrix

is called the Jacobian matrix of the system. It contains the first order partial derivatives of

f and

g evaluated at the point

(x,y). Now

Evaluating (

6) respectively at the four critical points (

4) results in

The eigenvalues of (

7), (

8), (

9) and (

10) respectively are

2.4. Stability of Model

The determination of the critical point’s type and stability (x, y) can be achieved through an assessment of the eigenvalues derived from the Jacobian matrix. Let’s denote these eigenvalues as and . Let us consider the case where both and are non-zero.

Table 1.

Conditions on eigenvalues to ensure different stability

Table 1.

Conditions on eigenvalues to ensure different stability

| Eigenvalues |

Linear System |

Nonlinear System |

|

|

Nodal Source (Unstable) |

Nodal Source (Unstable) |

|

Nodal Sink (Stable) |

Nodal Sink (Stable) |

|

Saddle point (Unstable) |

Saddle point (Unstable) |

|

Degenerate Source or Nodal Source (Unstable) depending of the geometric multiplicity of

|

Source (Degenerate, Nodal, Spiral Source depending on the nonlinear terms) |

|

Degenerate Sink or Nodal Sink (Stable) depending of the geometric multiplicity of

|

Sink (Degenerate, Nodal, Spiral Sink) (Stable depending on the nonlinear terms) |

|

|

Spiral Source (Unstable) |

Spiral Source (Unstable) |

|

Spiral Sink (Stable) |

Spiral Sink (Stable) |

|

Center (Stable) |

Center, Spiral Sink , Spiral Source

(Stability cannot be determined based on ) |

2.4.1. Phase Portrait and Field Directions of the Model

The optimal approach to illustrate the system’s vector field involves simulating a plot with diverse parameter values. Given that a static representation of the vector field necessitates fixing the parameter values, we present several potential scenarios through three specific cases.

3. Results

3.1. Model Interpretation and Conclusion

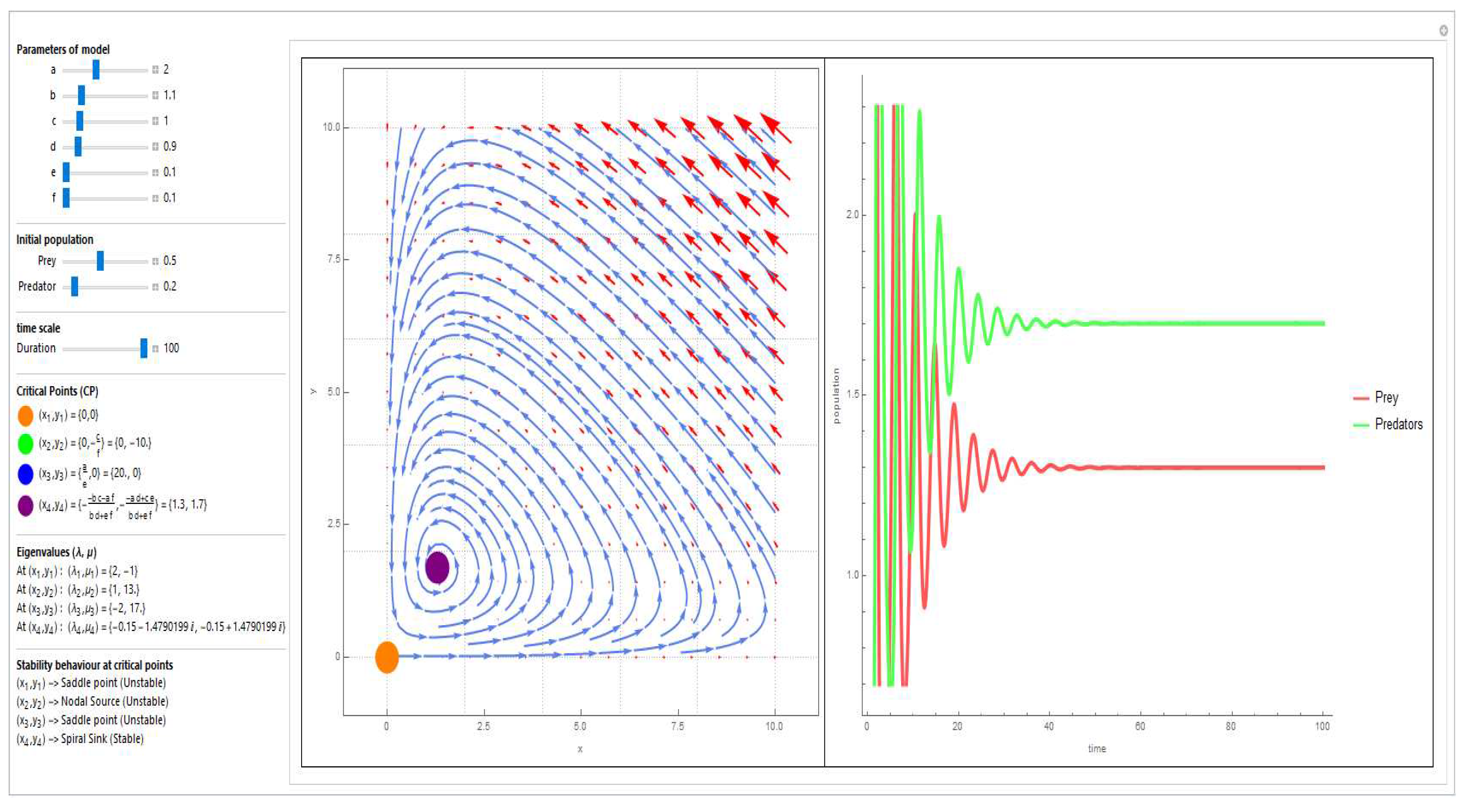

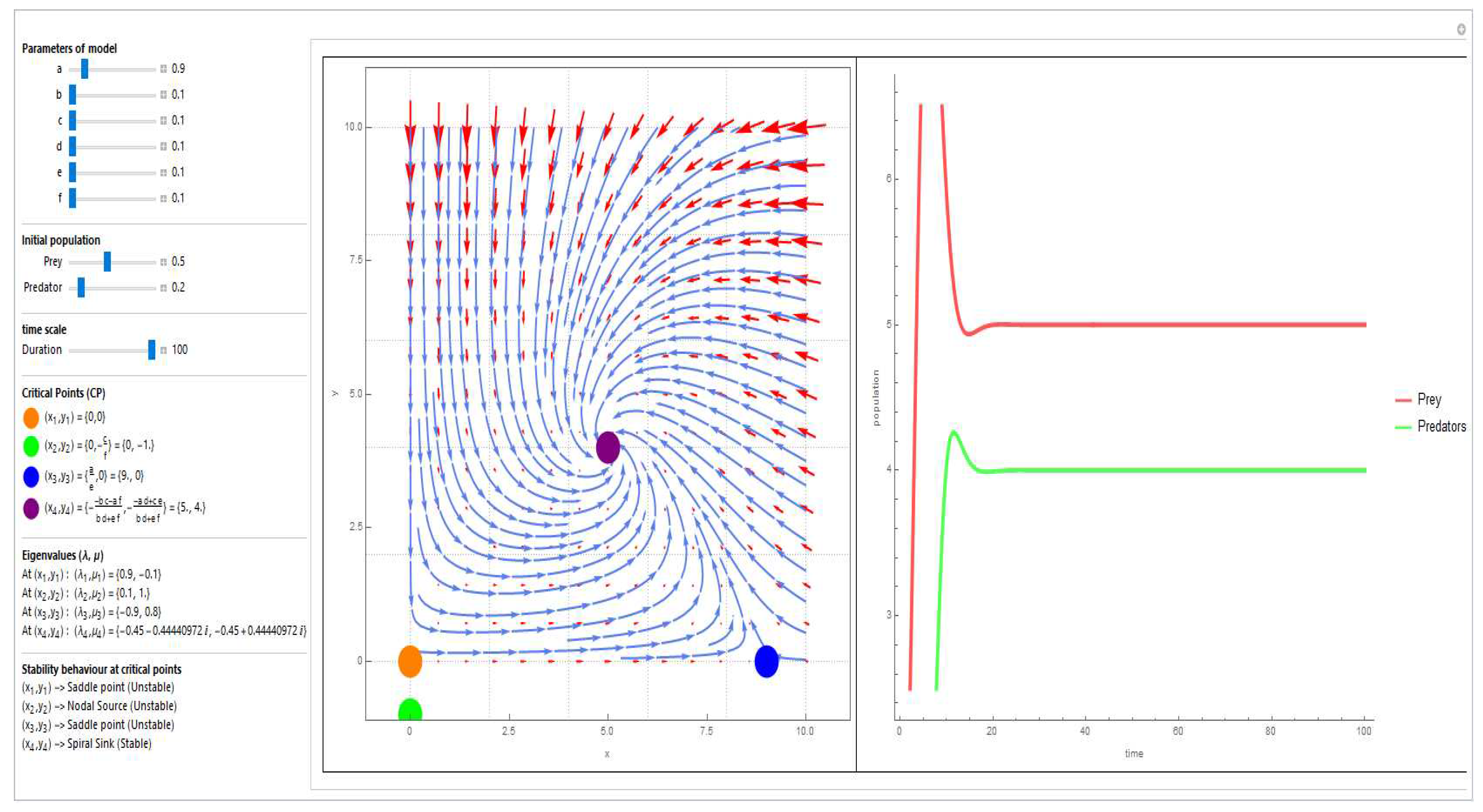

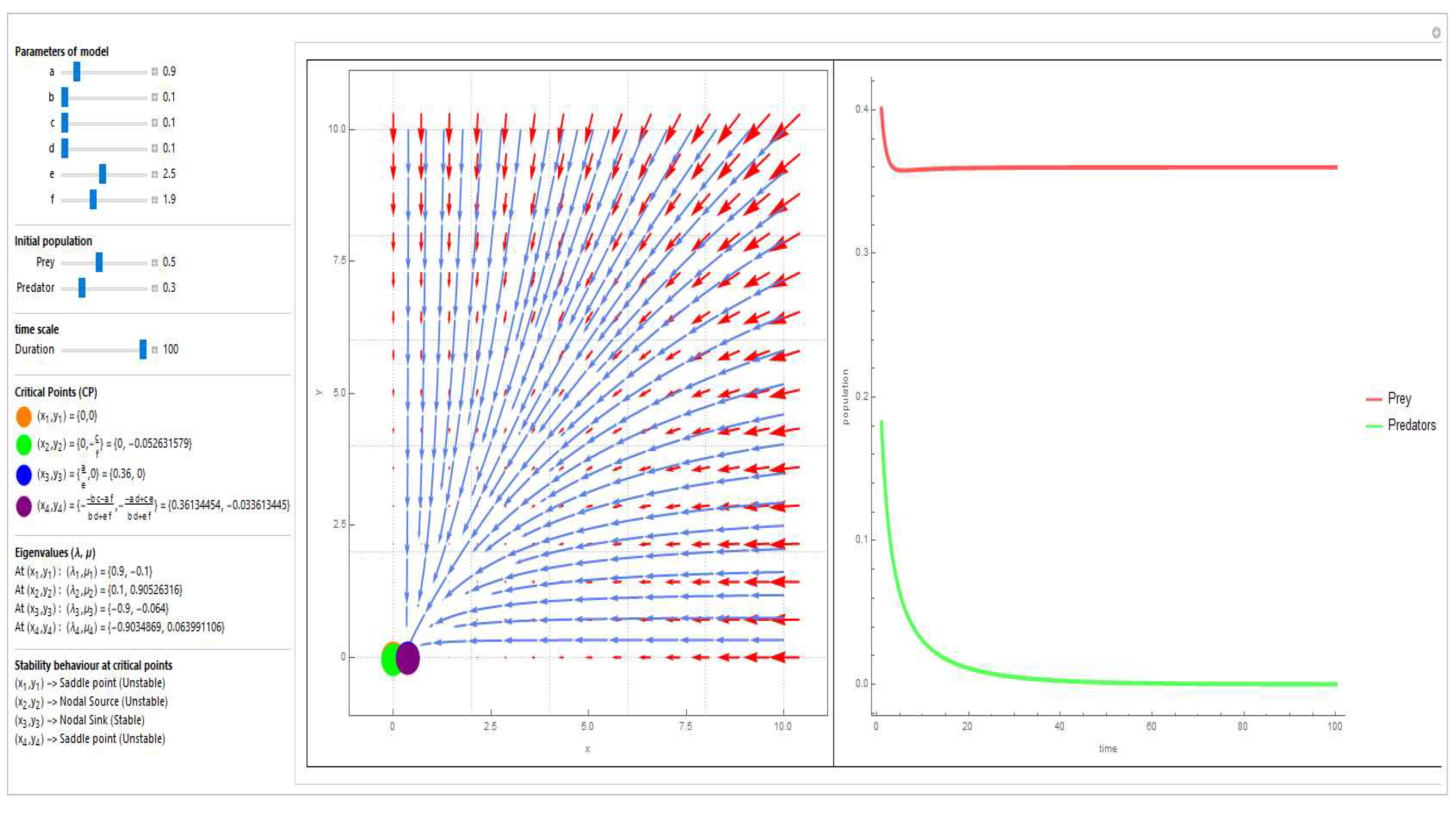

The depicted

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 highlight that the stability of distinct critical points is contingent upon the model’s parameter values. Considering the level of internal competition introduced between the predator and prey, the trajectories illustrated in these figures portray a non-periodic nature, converging towards an equilibrium state as time progresses. As a result, the system described by Equation (

2) manifests asymptotic stability. This observed behavior aligns seamlessly with the dynamics typically observed in natural predator-prey systems.

4. Conclusion

In our exploration, we have successfully adapted the traditional Lotka-Volterra equation by incorporating components that reflect the extent of internal competition within the predator and prey populations. Unlike the classical model, this adjustment has demonstrated the system’s tendency toward asymptotic stability, aligning more closely with real-world observations of natural predator-prey interactions.

Looking ahead, there is ample room for further research in this domain. One avenue of expansion involves the inclusion of additional variables to enhance the model’s fidelity, providing a more comprehensive and accurate representation of the intricacies inherent to the system under study. This step promises to deepen our understanding of the dynamics governing sustainable fisheries, bolstering our ability to craft effective management strategies for these critical ecosystems.

References

- Malthus, T.R. An essay on the principle of population, as it affects the future improvement of society. With remarks on the speculations of mr. Godwin, m. Condorcet, and other writers. By TR Malthus; 1817; Vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Lotka, A.J. Analytical note on certain rhythmic relations in organic systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1920, 6, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volterra, V. Fluctuations in the abundance of a species considered mathematically. Nature 1927, 119, 12–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierotti, R. Reviewed Work: Modeling Nature 1986.

- Benz, K.; Rech, C.; Mercorelli, P. Sustainable Management of Marine Fish Stocks by Means of Sliding Mode Control. 2019 Federated Conference on Computer Science and Information Systems (FedCSIS); IEEE, 2019; pp. 907–910. [Google Scholar]

- Amirian, M.M.; Towers, I.; Jovanoski, Z.; Irwin, A.J. Memory and mutualism in species sustainability: A time-fractional Lotka-Volterra model with harvesting. Heliyon 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whipple, S.J.; Link, J.S.; Garrison, L.P.; Fogarty, M.J. Models of predation and fishing mortality in aquatic ecosystems. Fish and Fisheries 2000, 1, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaf, Z.I.A.; Azmi, A.S.; Azami, S.N.H.; Hassan, S. The Effect of Two-Species Competition on a Lotka-Volterra Fishery Model in the Presence of Toxicity 2021.

- Darwin, C. On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life; Murray: London, 1859. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).